Around three-quarters of the way through Medium Cool (Haskell Wexler, 1969), Eileen (Verna Bloom) searches for her missing son, Harold (Harold Blankenship), in their Chicago apartment.[1] The scene is filmed in a single long take, a smooth handheld tracking shot that follows Eileen’s movement from one room to the next. The length, fluidity, and complexity of the shot noticeably break with the stylistic patterns so far established by the film. In his extended American Cinematographer profile, “The Filming of Medium Cool”, Herb Lightman recounts the events of the scene in scrupulous detail. “All of this action”, Lightman emphasizes, “was filmed in a single continuous shot, with Wexler smoothly propelling his hand-held camera to follow it.”[2] Beyond accentuating its technical distinction, however, Lightman’s protracted description leaves untouched the possible motivations behind this virtuoso camerawork. No doubt, as an innovative cinematographer, Wexler hardly needed an excuse to experiment with a handheld tracking shot. Yet, as Lightman explains, a similarly lengthy tracking shot in an earlier scene with a motorcycle courier had been discarded by the director because he didn’t think it important enough to the story.[3] In contrast, Wexler must have considered the long take in the apartment – the only shot of its kind in the finished film – to be narratively significant. But what is the nature of that significance? Why was the sequence staged in this way, and what does it reveal about the film more generally?

To begin to answer these questions we might consider the focus of the scene and its placement within the film’s narrative arc. Until this moment the action has primarily centred on the cameraman, John (Robert Forster), and his sound operator, Gus (Peter Bonerz). Now, the smooth, embodied movement of the camera around the domestic interior aligns the audience with another point of view, that of Eileen, just as we make the transition into the final act. The long take therefore establishes a purposeful, carefully-crafted pivot in the audience’s identification, which leads into the climactic, documentary-style footage of the Democratic National Convention (DNC). These legendary scenes of protest and police violence are framed by Eileen’s journey from the Appalachian slums of Uptown through the streets and parks of downtown Chicago in search of Harold. One thing that this long take offers, then, is a decisive shift in gendered subjectivity that subsequently shapes the most celebrated and critically valued sequences of the film.

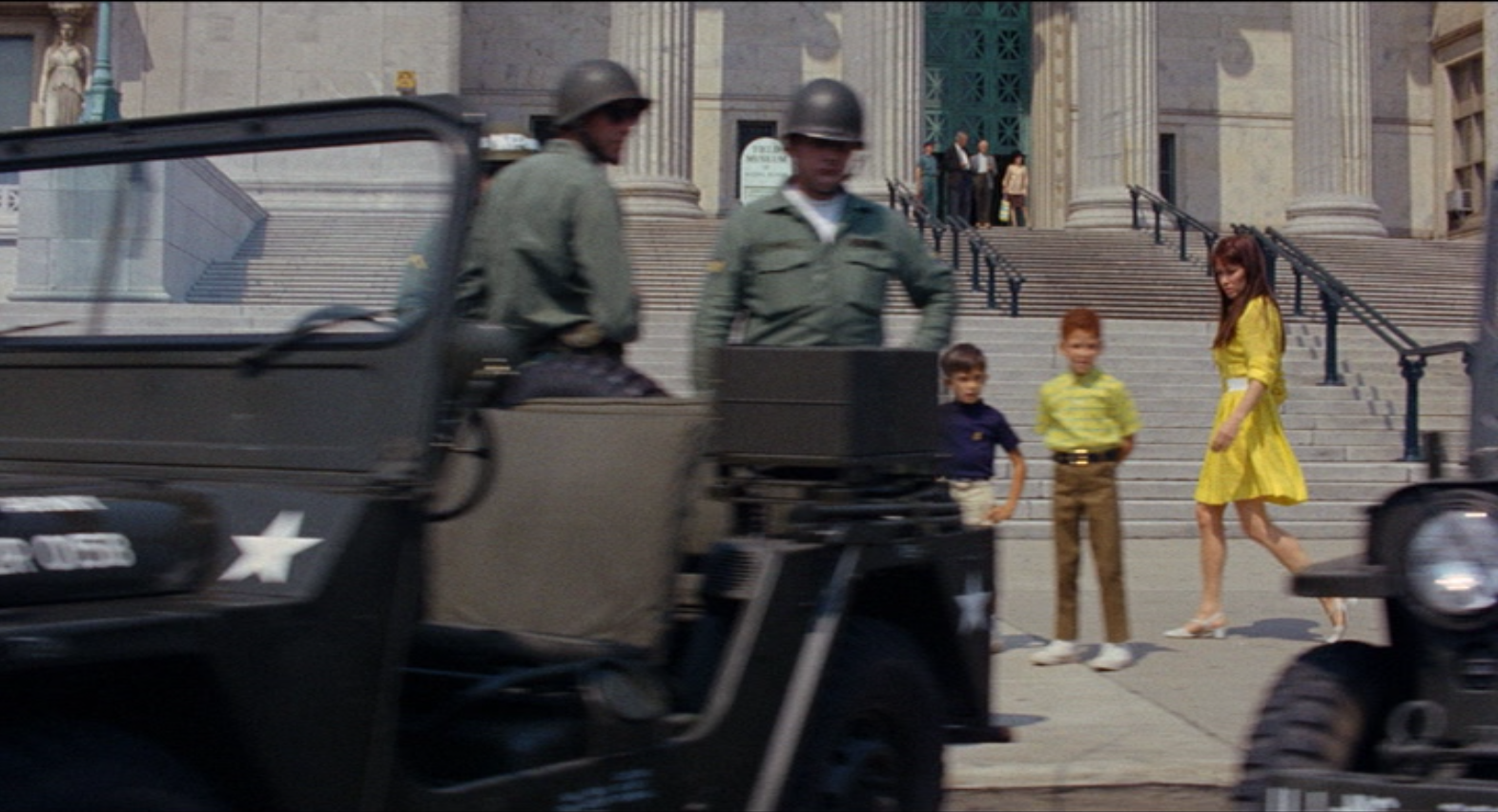

Yet the importance of Verna Bloom’s performance to this crucial final section of Medium Cool is often played down. In part, this is due to the value assigned to the film’s engagement with historical ‘reality’. Medium Cool‘s striking fusion of documentary and fiction practices has long fascinated viewers and critics, and for many commentators the film’s legacy is guaranteed by its vérité-style capture of the turbulent events of Chicago 1968.[4] This view is perhaps best encapsulated by the documentary scholar Michael Renov in his classic piece on the film, in which he argues that, in the final instance, “the fictional characters turn out to be far less important than the history that surrounds them”.[5] Renov suggests that Wexler intentionally allowed the historical events to overwhelm the fictional framing of plot and character. In contrast to a conventional Hollywood feature, Renov writes, “‘place’ (the summer 1968 Chicago setting) generates dramatic action and, in the end, annihilates it”.[6] But according to this account, the female protagonist Eileen all but dissolves into the scenery at the end of the film, becoming “reduced from character to a site of nominal motivation for the imagery, a figure dispatched to the edges and into the depths of the frame.”[7] Ultimately, for Renov, Eileen is “only slightly more distinguishable than a patch of yellow affixed to a passing jeep”.[8] A similar view was also offered by some of the film’s initial reviewers. Joe Morgenstern, for example, wrote in Newsweek that “Miss Bloom is actually, amazingly wandering around the fringes of the rioting in search of her lost son, but the lost son is a transparently melodramatic pretext for following a tour guide in a yellow dress in a brief travelogue of violence”.[9]

But is the character of Eileen best viewed as a formal construct – “a tour guide in a yellow dress”, even “a patch of yellow” – or something more complex? While acknowledging some of the limitations of Eileen as a character, I want to consider what’s at stake in this marginalization of the female protagonist in critical accounts of the film. This article pulls Eileen (and Verna Bloom) out of the background and into the foreground, reconnecting her with precursors in the New Wave cinemas of the preceding decade. At the end of the 1960s, the woman wandering solo through the streets of the city was a figure of cinematic and political significance. As Mark Betz has argued, the “wandering woman” was a significant trope in European art cinema of the 1960s, especially in the work of Agnès Varda, Jean-Luc Godard, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Louis Malle.[10] But, as I’ll explore, we can also find a crucial prototype in Judith McGuire (Barbara Baxley), a divorcée wandering through a seedy Los Angeles landscape in The Savage Eye (Ben Maddow, Sidney Meyers, and Joseph Strick, 1959), a pioneering fiction-documentary crossover on which Wexler worked as a camera operator alongside the influential photographer and documentarist Helen Levitt.

Such an image of the woman walking alone in the city streets, unmoored from the determining structures of work, marriage, or domesticity, has been an important conceptual figure for feminist writing on literature and cinema. Viewing Medium Cool within this critical and cinematic lineage helps to recover the importance of Eileen to the filmmakers’ political project and allows us to reconstruct her radical potential as one of New Hollywood’s wandering women. Paradoxically visible and transparent at the same time, Eileen cuts an ambivalent figure, however. Throughout the climactic scenes of the film, Eileen holds a dual status: she is simultaneously an object in the frame (the “woman in the yellow dress” who anchors the documentary footage) and a viewing subject, a flâneuse who confronts world-historical events in the streets and public spaces of the city. She is arguably central to the film’s politics just as she encapsulates some of its contradictions and tensions. We can therefore simultaneously read the marginalization of the character in critical discourse on the film, along with the removal of key scenes during editing, as emblematic of the missed connections between New Hollywood and second-wave feminism. And zooming out from the text to its production history, embedded in the critical legacy of the film is a parallel story of the displacement of female creative labour in New Hollywood historiography. While Wexler has (rightly) been widely praised for his achievements, some of his key collaborators behind the scenes – especially editor Verna Fields, assistant editor Marcia Lucas (née Griffin), and sound editor Kay Rose – have, like the woman in the yellow dress, been rendered invisible by dominant critical paradigms that prioritize the individual work of the male auteur over the collaborative creative labour of post-production.

Critical frames: promotion and reception

To understand how these elisions first developed, it’s instructive to examine the film’s initial promotion and reception. Looking closely at studio marketing and early reviews reveals patterns of interpretation that have shaped subsequent engagements with the text and framed the public narrative of its production process. Paramount was uncertain how to market Medium Cool, and its promotion reflects a broad array of perceived attractions including critical prestige, technical innovation, topicality, countercultural cool, and sexual frankness. Out of this unstable mix, key interpretive frames and elements of behind-the-scenes lore emerged; initially established by the studio press release and marketing materials, these were soon amplified by the film’s initial reviewers. This promotional surround has influenced critical engagement with the text in several significant ways.[11]

In the first instance, the studio publicity book explicitly defines Eileen’s character as a political naïf who does not comprehend the events she witnesses. According to the synopsis supplied to film critics, Eileen “does not know what any of it is about and is only vaguely aware of the tanks and National Guardsmen on the city’s streets … Unwittingly, she falls into step with the demonstrators, kneels when they kneel, walks when they walk and runs with them when they begin to flee the tear gas”.[12] Reviewers largely followed this lead. Richard Corliss, for example, wrote that “The convention itself has no demonstrable effect either on [the protagonist] or on Eileen, who is, after all, only looking for her run-away son.”[13] Some writers praised Bloom’s naturalistic performance, while simultaneously trivializing the character as “a housewife” or merely “the love interest”.[14] Other critics were entirely dismissive: the Motion Picture Exhibitor review, for example, lazily conflated the two female characters while dismissing their relevance to the film in one sentence (“Bloom and Hill are merely objects of [John’s] passion, Barbie dolls with big eyes, big breasts, and little brains”[15] ). Despite Eileen’s evident importance to the protest sequences, the possibilities of viewing her as a significant character with her own agency and desires, or understanding the protest scenes as a political awakening, were largely foreclosed.

The Paramount press book also pushes Wexler’s documentary-style working practices as exceptional and innovative. The challenging and risky location shoot, on which the crew members were hassled by police and subjected to teargas, emerges in the press release as a core element of the film’s commercial identity, especially as a guarantee of artistic integrity and place-based realism (“not one studio scene was used for the entire film and the characters responded with an authenticity which could never have been achieved on sound-stages”).[16] American Cinematographer likewise praised the crew for working “on the fly under hazardous conditions”.[17] Such a narrative certainly spoke to the unique status of the protest sequences, which were radically new in the context of the Hollywood feature film, yet by amplifying the drama of principal photography and playing up the importance of the historical events captured onscreen, these early accounts tended to diminish other vital aspects of the film’s assembly, from performance to post-production. Over time, this approach has to some extent encouraged critics to view the protest scenes as an almost unmediated capture of a historical event, or to use “documentary” as a shorthand for committed engagement with the profilmic reality of Chicago ’68. Both of these essentially gendered critical frames – from the dismissive treatment of the female characters to the elevation of the “masculine” endeavour of the location shoot over the labour of post-production – have moved attention away from Verna Bloom/Eileen and implicitly devalued the collaborative cinematic craft of the protest scenes.

|

|

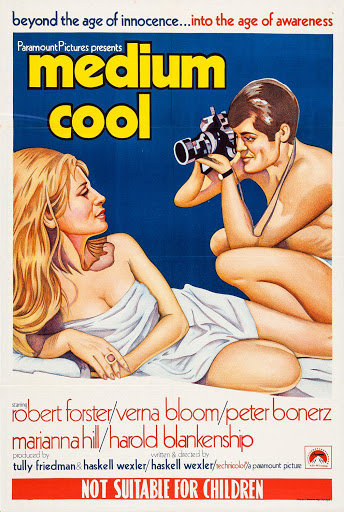

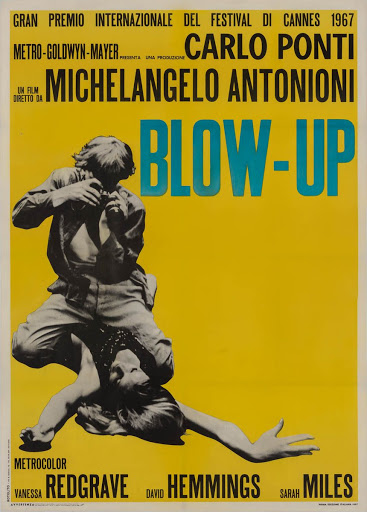

Such mythologization of the location shoot was also reinforced in the film’s initial reception by a strong auteurist frame of reference. Films and Filming celebrated Wexler’s all-round achievements, noting that “not only did he direct, he also wrote the screenplay, co-produced, master-minded the camerawork and participated with his crew in the thick of the rioting”.[18] Lightman’s American Cinematographer article, which incorporated large chunks of text verbatim from the studio press release, mused at length on the meaning of the term ‘auteur’ and compared Wexler to other “men of multiple talents” (emphasis mine) such as Orson Welles and Stanley Kubrick – directors he surpasses, Lightman asserts, by being “the first to write, co-produce, direct and photograph a full scale dramatic feature for major release.” [19] The press book and posters amped up the film’s similarities to Blow Up (1966) and encouraged the idea that the “punchy cameraman” John was a stand-in for Wexler himself, however misguided that idea might have been. Presenting the macho cameraman as a proxy for Wexler, as many reviewers also did, only shored up an auteurist reading of the film and its production process – a view underscored by the sense that documentary filmmaking on the streets, textually linked through John to war reporting, should be seen as an especially masculine field of action. Wexler may have had similar things in mind when he confided to Film Quarterly that if making a studio picture was like “making love with all your clothes on”, shooting documentaries on location offered a “terrific sexual feeling of just getting in here, you know”.[20] He was likely trying to convey the electric charge of working outside the studio in fast-moving improvisatory context, but the comments nevertheless recall some of the masculinist tendencies that have always marked auteurism – perhaps most famously, Andrew Sarris’s repeated use of the term “virile” to praise his preferred auteurs (a word choice that Pauline Kael was quick to deride in her sharply funny takedown of Sarris and auteur theory).[21] In any case, these mutually reinforcing linkages between masculinity and authorship, which reverberated back and forth from text to production context, helped frame Medium Cool through an auteurist lens.

Editing Medium Cool: post-production and female labour

There could be no Medium Cool without Wexler, of course, yet this almost exclusive focus on the director as the film’s creative engine has left significant blind spots. In particular, the predominantly female post-production team are largely missing from critical accounts of the film, despite their subsequent successes. The editor, Verna Fields, and her assistant editor, Marcia Lucas, later won Academy Awards for editing the two biggest hits of the 1970s – Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977), respectively – while the sound editor, Kay Rose, received a Special Achievement Award for Sound Editing on The River (1984). Although they had yet to hit their career peaks in 1968-9, Fields, Lucas and Rose were vital creative talents and played no small role in shaping New Hollywood cinema over the following decade. Yet their contributions to Medium Cool have all but vanished from discussions of the film in scholarship, criticism, and paratexts such as DVD commentaries. Key academic texts on the film rarely acknowledge Fields, Lucas and Rose, for example, though this is perhaps unsurprising as much of this work does not focus on production history beyond the mythologized location shoot, and the three women are not mentioned in the DVD Director’s Commentary with Wexler, Marianna Hill, and Paul Golding (whose role I will discuss below).[22] Such marginalization of the predominantly female post-production team in the critical legacy of Medium Cool mirrors the broader allocation of prestige to creative roles in Hollywood, which, as Erin Hill argues, has always been bound up with gender.[23] As Maya Montañez Smukler has shown, women were entering the film industry in greater numbers in the 1960s and 1970s, but they were often pushed to the margins by the brand power of the male auteur.[24] For this reason, untangling individual contributions can often be challenging. Though it’s beyond the scope of this article to reconstruct the specific inputs of Fields, Lucas, and Rose to Medium Cool at a micro level, in the close scene analysis that follows I’ll emphasize the central role of editing image and sound in creating a coherent narrative experience from the multiple hours of footage taken at the DNC protests. But first, I want to turn to the editor, Verna Fields, whose connections with Wexler reveal patterns of collaboration and influence that move our understanding of the film away from the mythology of the male auteur.

Of the three women involved in its post-production, Fields was the most experienced at the time of Medium Cool. She had apprenticed at Goldwyn Studios and later honed her skills on documentaries and educational films for various public agencies, including the Office of Economic Opportunity and the National Film Board of Canada. During the 1960s, she taught at the University of Southern California, where her class included notable figures such as George Lucas, Walter Murch, Gloria Katz, John Milius, Matthew Robbins, and Marcia Griffin (who would marry Lucas in 1969). Fields enjoyed a close relationship with the “movie brats”, especially Steven Spielberg, and she embraced her maternal image as “mother cutter”, which would come to define her bond with the young directors she supported.[25] “That’s when she became our den mother”, recalled Frank Marshall, who produced Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). “When I was 24, we went to Rome to do Daisy Miller [1974]. I stored all my worldly possessions in Verna’s garage … She always gave you the feeling she was there for you, night or day.”[26] Nicknames such as “den mother” and “mother cutter” were transparently loaded with gendered assumptions, yet they also reflected her distinctively collaborative working style, which was at odds with both the emerging orthodoxy of auteurism and the carefully policed boundaries of the Hollywood craft unions. Indeed, Fields’s unusually flexible working relationship with directors such as Peter Bogdanovich and Spielberg led the Editors’ Guild to reprimand her for blurring the functions of the director and editor, which they felt undermined the disciplinary autonomy of the craft.[27] In the case of Medium Cool, the individual contributions of Fields are difficult to assess fully because Paul Golding, another USC alumnus, was hired by Wexler to edit alongside Fields, though he was unable to be credited as editor without membership of the Guild. It’s ironic that in this instance Fields would take official credit for work that was shared between her and a junior colleague. Nevertheless, it’s unlikely that a male editor with her track record would have ceded ground to an untested film student, yet Fields – as ever playing her supportive role as “mother cutter” – allowed Wexler to work with Golding while she provided oversight, especially as a consultant on the final cut.[28] Her collaborative style therefore provided space for experimentation with new talent, and her extensive experience as an editor inside and outside of Hollywood, as well as the skills of her protégé and assistant editor Marcia Griffin were central to Medium Cool‘s merging of documentary and fiction practices – which took place in the cutting room as much as on the streets of Chicago.

The Savage Eye: collaboration and influence

Wexler’s working methods were flexible and collaborative too, more so than the auteurist media discourse around the film would suggest, and, like Fields, his habits had been shaped by formative experience outside of the studio system. His creative relationship with Fields began several years earlier on The Savage Eye (1959), a collectively produced independent film that prepared the ground for Medium Cool in several important ways. Described by the filmmakers as “the story of an American woman’s journey through one year of divorce and her discovery of love amid the violence and splendor of a modern city,” The Savage Eye created an innovative mix of documentary footage, dramatic scenes, and poetic voiceover.[29] It was written and co-directed by three notable figures who straddle documentary, art film, and Hollywood: the director and editor Sidney Meyers (best known as the director of The Quiet One [1948]); the director Joseph Strick (most famous for his 1967 adaptation of James Joyce’s Ulysses); and the blacklisted screenwriter and documentarian Ben Maddow (co-writer of The Asphalt Jungle [1950] and, uncredited, of High Noon [1952], The Wild One [1953] and Johnny Guitar [1954]). Beyond the unusual three-way directorial credit, the working environment was radically collective and flexible in comparison to studio filmmaking (as Fields’s case suggests, craft boundaries in Hollywood were often rigidly maintained). Wexler was hired as one of three cinematographers, alongside Jack Couffer (author of The Concrete Wilderness, officially Medium Cool‘s source text) and the photographer and filmmaker Helen Levitt, while Verna Fields spent seven months working on the editing and sound. This fortuitous meeting of talents created professional networks that would help forge Medium Cool several years later, though the process of collaboration wasn’t always smooth, and working outside the studio system had its drawbacks – according to The New Yorker, it took four years to produce the film, during which time the participants worked unpaid.[30] Nevertheless, when it finally emerged in 1959, The Savage Eye was warmly received on the art-house and film festival circuits in the US and Europe.[31]

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Savage Eye is rarely discussed in relation to Medium Cool, but there are striking connections between the two films. In the first instance, there are some salient thematic correspondences. We might compare, for example, the scenes in both films staged at a real roller derby bout, which is a distinctive and unusual setting for the period and can hardly have been a coincidence. In both cases, the actors are filmed watching unscripted live events unfolding, and each film uses this encounter to offer an implicit critique of the spectacle of staged violence and its enthusiastic reception by the crowd. Both films also contain graphic footage of automobile accidents: the protagonist, Judith, crashes her car towards the end of The Savage Eye, though unlike Eileen, she survives. Beyond these narrative motifs, there are clear similarities in working methods between the two films. As in Medium Cool, the filmmakers of The Savage Eye placed professional actors within unstaged events, often filming without official permits, which allowed them to capture essentially improvised documentary footage yet frame it within a coherent narrative diegesis. And in aesthetic terms, the use of handheld cameras, available light, and the landscapes of urban decline in The Savage Eye was several years ahead of similar developments in Hollywood, where ‘grit’ had yet to become a sought-after quality. As Couffer recalls, “Joe [Strick] wanted a gritty style for a daring movie, and we gave it to him with black-and-white film and natural illumination as we found it in seedy skid row locations”.[32]

Alongside these close correspondences in techniques and aesthetics, The Savage Eye also prefigures Medium Cool through its female protagonist, Judith, whose interior monologue and subjective viewpoint frames the vérité-style exploration of Los Angeles. Such an approach was almost certainly influenced by another one of the film’s creative collaborators, Helen Levitt, at that time arguably the most accomplished of the camera crew. By the mid-1950s, Levitt (born 1913) had exhibited her street photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and had worked on two important documentaries, In the Street (Helen Levitt, Janice Loeb, and James Agee, 1948) and The Quiet One, with Sidney Meyers. Though Levitt’s specific contributions to The Savage Eye have never been officially identified, Jan-Christopher Horak notes that they are relatively easy to establish through comparison with her earlier work. “The two major sequences of Levitt’s imagery,” Horak observes, “are framed within the narrative by woman’s subjectivity and her gaze.”[33] For Horak, these moments offer “a topographical exploration by the female protagonist, marked as her subjective view”.[34] This meeting of topographical exploration and female subjectivity is central to The Savage Eye more generally, not only in Levitt’s sequences, and it provides a structuring framework for the filmmakers’ exploration of the city. A similar approach would later inform the protest sequences of Medium Cool. Placing the films together shows that The Savage Eye didn’t just pioneer the fusion between documentary and fiction practices that would later define Medium Cool – more specifically, it deployed a woman walking through the city as a strategy for mixing the two modes. Though Wexler rarely discussed The Savage Eye, which by the late 1960s had largely been forgotten despite its relative success, working alongside Fields and Levitt was undoubtedly a formative experience that influenced the filmmaking process and content of Medium Cool, from its documentary techniques to its wandering female protagonist.

The protest scenes: techniques and aesthetics

To reassess the importance of Eileen – and Verna Bloom – to Medium Cool, I’ll first return in some detail to the protest scenes and the filmic construction of what Renov calls her “street odyssey”. Viewing Eileen as a protagonist may seem counterintuitive. After all, she’s certainly an underdeveloped character with relatively limited screen presence and dialogue. Through much of the film she is secondary even to her son in terms of narrative weight. Yet the climactic scenes of protest and violence are framed by her walk through the city: the visceral, bloody reality of the Chicago ’68 police riot is filtered through her experience, not that of the male protagonist, television journalist John Cassellis. And though the film never quite makes good on the promise, it invites us to entertain the idea that she is undergoing a political epiphany, as I’ll explore below. All of this is made possible by Verna Bloom’s performance, which was so naturalistic that some commentators mistook her for a non-professional actor. It’s a testament to Bloom’s compelling and empathetic presence that despite her relative lack of screen time she was frequently held up as the film’s emotional centre. But it would be a mistake to view Eileen only as a romantic subplot or a short-cut to audience sympathy, as many critics have. Contrary to some accounts, Eileen does not dissolve into the background during these sequences. Looking closely at choices of staging, framing, editing, and performance reveals how the protest scenes are built around Eileen and her movement through the city. And because Bloom’s performance focuses the audience’s engagement and identification in the final scenes, she helps generate Medium Cool‘s productive tension between documentary and fiction practices. Eileen may not play a central role throughout the film, but she is nevertheless vital to Medium Cool both cinematically and politically.

|

|

As I’ve suggested, the long take in the Uptown apartment subtly yet firmly signals an intent to reframe Eileen as the film’s dramatic centre, and to move away from the male protagonist. It allows us to focus, in real time, on her everyday actions as she returns home: looking in the mirror, unbuttoning her dress, and slipping off her shoes. She’s searching for Harold, though at this point, she’s not overly concerned, and the scene has a contemplative quality. As she moves through the apartment, the handheld camera stays close to her. Rather than directly adopting her point of view, the camera establishes alignment with Eileen through a sense of proximity to her movements and gestures. After checking for Harold on the roof, she sets out into town on the L train. Once downtown, we are confronted with a few brief images and sounds of protestors and police clashing on the streets, which prefigure the violence of the following day. But our attention is soon directed back to Eileen through a series of wide shots that situate her in the environment. Sounds of the demonstrators, police sirens, and car horns are layered over a long establishing shot, which pans across the downtown skyline at night, taking in landmarks such as the Wrigley Building and the Tribune Tower, then tilts down to find Eileen as she ascends some steps from the riverfront onto East Wacker Drive. Her relatively slow walk over the bridge and across the street is followed at a distance with a long lens, emphasizing her as a small figure within an enveloping urban landscape. Taken together, the two scenes – detailed movement through the apartment interior, followed by the journey through the night-time streets – place Eileen within two contrasting yet carefully rendered social environments. By accentuating first proximity and then distance, they establish the visual logic of the protest scenes and begin to reveal Eileen’s dual status as viewing subject and object-in-the-frame.

|

|

|

|

Her journey the following morning splits into four distinct sections: a relatively peaceful walk through the crowds in the park, before the violence kicks off; walking on the streets, as she falls in and out of step with the march; violent and disorienting scenes of clashes between protestors and police; and a series of sustained, lateral tracking shots that follow Eileen as she walks past lines of troops outside the Field Museum. Each section has specific stylistic strategies, but there are a number of shared approaches that use Eileen/Bloom to anchor the protest footage both visually and emotionally. As with the film in general, the protest scenes have often been discussed in terms of documentary aesthetics, in part because Wexler actively introduced practices more readily associated with the direct cinema movement. Handheld camerawork, close mobile framing, liberal use of zoom lenses, and allowing people and vehicles to obstruct the shot momentarily may have been well-established facets of ’60s documentary film, but such techniques had yet to become the stock-in-trade of Hollywood cinematographers[35] . In Medium Cool they inject the protest scenes with a sense of immediacy, contingency, and unfiltered “actuality”, building on a wider set of documentary-style strategies (direct address, non-professional actors, improvisation) introduced earlier in the film. Nevertheless, we shouldn’t lose sight of the more conventional feature film principles at work in the protest scenes, especially as they relate to the role of Eileen/Bloom. Though Wexler had worked extensively in documentary, he was also in demand as a Hollywood cinematographer – most recently, for In the Heat of the Night (1967) and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) – and had an equally solid grasp of the modus operandi of a studio feature. The same was true of Fields, whose varied career ranged from making agricultural films for the Office of Economic Opportunity to cutting the Anthony Mann epic El Cid (1961). Drawing on this dual formation, the filmmakers were able to fuse non-fiction and fiction practices both on location and in the editing suite. Several hours of material were artfully condensed by Wexler and his post-production team into an impactful 20 minutes or so of running time. Given that no synchronized recordings were made at the time, Kay Rose’s sound editing also does a remarkable job of creating the intense sonic experience of the protests. The audio track jumps back and forth from non-diegetic score to an immersive, multi-layered sound collage that takes in crowd noise, traffic, protestors chanting, police sirens, radios, and brief snippets of off-screen dialogue. Because the filmmakers were so successful at editing both sound and image, it has often seemed as if the fictional dissolves into the real here, but this elides the craft – and the labour – that went into the assembly of these scenes. The footage is expertly edited to capture the feel of the events, without showing too much violence for a studio release, and the protest scenes both sustain attention and create empathy by placing the viewer into the crowd. Bloom’s performance merges with the unscripted events and allows the audience members to become, through Eileen, witnesses to the historical moment.

|

|

|

|

While the cinematography and staging firmly establish a documentary register, Bloom/Eileen is generally kept centred in the frame, with medium close-ups deployed at key moments to provide a narrative focal point and a source of identification. The initial scenes in the park establish these patterns. Observational, documentary-style footage of the crowds gathering alternates with shots that are firmly centred on Eileen in her yellow sundress. Keeping Eileen in focus in the middle of the visual field maintains our connection to the character, while the developing scene around her establishes a complex sense of depth and layering. Just as Eileen is looking for Harold, we are invited to scan the frame for salient details, such as the ominous appearance of a police van snaking into the deep background of the shot. As the scene progresses, close mobile framing creates a sense of dynamic immediacy and the perceived ‘liveness’ of an event unfolding. Wexler et al do not tend to reproduce Eileen’s look in direct point-of-view shots, but rather show her as an observing agent within the diegesis. Here and throughout the protest scenes the action is not cut according to strict continuity principles, yet the patterned movement between shots containing Eileen and shots in which she does not appear nevertheless establishes her as a visual and identificatory anchor.

|

|

|

|

The second section shifts from the park to the streets, where Eileen’s walk intersects with the collective movement of the crowd. Whereas the first section creates a sense of separation between Eileen and the protestors, the second begins to align her with it, as she moves in and out of step with the collective on the street. As Jon Lewis aptly puts it, these scenes are driven by the “aimless locomotion” of the “ambling throng”.[36] Though that sense of ambulatory locomotion is partly a property of the crowd, as Lewis argues, it’s also framed for the camera by the movement of a female body. Depending on the vantage point, that body is both part of the crowd and distinct from it, and it is this blurring between individual and collective, subject and object, that is critical. As the police violence escalates in the third section, shot in Grant Park, the framing becomes tighter, the handheld camera is jerkier, and the editing is more rapid and disjointed. But amid this sense of fragmentation, we return repeatedly to Eileen. She is not pushed to the edges of the frame, as Renov suggests – in fact, she is very often placed at the centre of the shot, and the filmmakers return insistently to her face in close-up to provide a focal point and an emotional anchor in the mêlée. While it is undeniably the “yellow dress” that allows us to locate Eileen rapidly in the frame, close-ups of her face also allow Bloom’s performance to connect with the audience. Her presence therefore makes the scenes not only immersive and emotionally impactful, but also legible and coherent, allowing the viewer to follow what might otherwise seem like unstructured material. Throughout, the filmmakers combine techniques that establish documentary-style immediacy and a sense of televisual liveness with more conventional feature film framing and editing patterns that work to personalize the events.

|

|

|

Far from dissolving into the backdrop, Eileen becomes more prominent in the final section of the walk. After the confrontation in Grant Park, which creates a visceral and emotional experience of police violence, we are presented with a more distanced but equally impactful visual representation of power. This is rendered in the final section by a series of Godard-inspired lateral tracking shots, which are formally distinct from the earlier sections of the protest. Though the camera’s bumpy movement suggests it is handheld, the scene is filmed from a moving vehicle. The shots play with multiple depth planes. In the first instance Eileen occupies the middle ground, with lines of National Guard troops in the background and parked cars in the foreground. In subsequent shots Eileen is framed against the steps of the Field Museum, with jeeps and troops between her and the camera. Towards the end of the scene the camera moves further away from her behind multiple layers of soldiers, jeeps, and military equipment. As before, Eileen is placed at the centre of the visual field both in terms of lateral distance across the frame and in terms of depth, remaining both the object of our attention and the viewing subject who organises and directs our gaze. Having been stirred by the sights and sensations of the protest, and by her first-hand witnessing of police violence, Eileen completes her “street odyssey” by apprehending the power of the military-industrial complex on display. The formidable line of troops and military hardware in front of the Field Museum invites the viewer to associate the city’s historic, civic institutions with the repressive, disciplinary power of the state. Whether we think of this as an ironic juxtaposition or as a kind of mirroring depends on how we read the museum – not least, its historical genesis in the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893[37] – but there’s no doubt that this is intended as the climax of Eileen’s personal and political journey through the city, which is underlined by the electrifying reprise of the title music, “Emotions” by Love.

|

|

|

|

If focusing on the relatively conventional (and individualistic) cinematic properties of character and identification here makes Medium Cool seem less outwardly radical, then it is worth remembering why the issue of narrative framing matters. As Wexler et al knew, Chicago ’68 was a media event from the outset – and one where the city had become a global stage (“the whole world is watching”). Footage of police beating protestors at the DNC was viewed by 90 million Americans on television news reports in August 1968[38] . These violent images, captured in colour by the major networks, quickly became some of the most resonant televisual moments of the decade, yet their political impact was contested across the political spectrum. While for the Left the imagery self-evidently portrayed the egregious misuse of police power, conservatives worked to mobilize Chicago ’68 as further evidence of social unrest in the cities, a tactic that played into Nixon and Agnew’s reactionary “law-and-order” rhetoric in the run-up to the November election[39] . As a televised event, the protests and police riot were politically malleable, then, and the images were not necessarily shocking to the viewing public on the film’s delayed release a year later. In this context, Eileen’s presence is essential for framing the Chicago footage on the political left, and as critics noted, incorporating palpably authentic documentary-style sequences into the narrative architecture of the Hollywood feature film heightened their impact for audiences. As Herb Lightman opined, it was precisely this combination of visual realism and emotional power that allowed the film to create “a filmic truth that is more ‘real’ in its effect upon the audience than, let us say, an actual newsreel of the events depicted”[40] . Yet the “realism” of Medium Cool is a complex question given that it is characterized both by its engagement with the historical “real” and by strategic efforts to undermine the seamlessness of the Hollywood feature. The protests and police violence are staged not as an objective record but rather as an immersive cinematic event, yet the film systematically works to unmask the process of mediation, right up to the final Brechtian reveal of Wexler behind the camera. As Jon Lewis writes, Medium Cool “effaces distinctions between the real and the staged,” and in doing so diminishes “the significance of the distinctions between subjectivity and objectivity”.[41] Eileen – the woman in the yellow dress – both symbolizes and makes possible that blurring of boundaries in these scenes, where the achieved effect is not so much the collapse of “fiction” into “reality”, but rather holding the two in productive tension. Her persistent presence in the protest scenes appears to envelop the real events into a seamless fictional experience, but at the same time her appearance in the frame constantly reveals the constructedness of the image. Eileen is not merely a “pretext”, then, but a crucial component in the production of Chicago ’68 as a cinematic spectacle.

Walking in the city: Eileen as “wandering woman”

When Wexler and his team placed Verna Bloom at the centre of a long, quasi-narrative urban journey filmed amongst the backdrop of real events, they were working with a character type rich in cultural meaning. As I’ve suggested, Eileen’s walk through the city draws on the immediate influence of Helen Levitt and The Savage Eye, but it equally reveals telling resonances with the walking female protagonists of European art film. Of course, Medium Cool has been much discussed in relation to European cinema before. Jean-Luc Godard was a key reference point in the film’s initial reception, though not always in favourable terms: Andrew Sarris slapped down the film’s “Godardian gimmicks” in The Village Voice, for example, while Time critiqued the “novice director’s infatuation with Jean-Luc Godard” and complained that the ending was “straight out of Contempt” [42] (Le Mépris, 1963). In Variety, Jerry Beigel drew more admiring comparisons between Medium Cool and Godard’s La Chinoise (1967) as two films that had accurately captured the radical ferment of the late ’60s[43] . Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) was frequently invoked too, largely as a comparison point for Medium Cool‘s cameraman protagonist: Cue praised the film as “an American Blow-Up“, while Joe Morgenstern dubbed it a “story of an alienated shutterbug” in a direct allusion to the photographer-turned-detective in Antonioni’s film, a connection reinforced by the poster image of a topless Robert Forster photographing the supine Marianna Hill in a clear visual echo of David Hemmings and Veruschka[44] . European cinema was an active component in the film’s marketing and reception, then, and it was variously used to evoke anything from continental sexuality to Brechtian metacommentary. But Medium Cool borrows something else from Godard, Antonioni, and their contemporaries: the female urban walker, a role memorably played by Jeanne Moreau in Lift to the Scaffold (Ascenseur pour l’echafaud, 1957) and La notte (1961), Monica Vitti in L’Eclisse (1962), Corinne Marchand in Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), and Anna Karina in Vivre sa vie (1962), to take just a few examples.[45]

Perhaps the most widely cited instance of the female walker is Florence “Cléo” Victoire (Corinne Marchand) in Varda’s Cléo from 5 to 7, a film which crystallizes the importance of the figure to feminist discourse. In what has become a canonical reading, Sandy Flitterman-Lewis argues that Varda’s film pivots around Cléo’s transformation from object-to-be-looked-at to viewing subject[46] . Expanding on this idea, Janice Mouton locates Cléo’s journey across Paris at the heart of this transition. Learning to discard her performance of the “feminine masquerade,” Cléo embraces the messy vitality of the city streets and takes up a newfound position as an observer of the social world rather than the object of the gaze.[47] Cléo’s movement around Paris allows Varda’s camera to capture the everyday textures of the city from street level – an embodied, feminine gaze that implicitly rejects the masculinist aerial view of the modern city planner. For Flitterman-Lewis, Mouton, and subsequent critics, Cléo’s urban journey has therefore symbolized liberation, self-discovery, and freedom – in particular, freedom from traditional constraints on women’s movement through and visibility in public space. By reading the female walker as a flâneuse, Mouton draws on a body of feminist scholarship which has explicitly challenged the masculine biases of the critical literature of modernity and the trope of the flâneur. As Elizabeth Wilson notes, the flâneur named “a new kind of public person with the leisure to wander, watch, and browse” in the 19th century city – a public person who was male by default.[48] And as Wilson shows, the flâneur embodied the male gaze, registering both “visual possession of the city” as well as “men’s visual and voyeuristic mastery over women”. In the first instance, the term flâneuse was invoked as an imaginary female counterpoint to this male archetype. Janet Wolff, for example, forcefully argued that the flâneuse was an “impossible” figure in the literature of urban modernity: only men had the freedom to walk and view the city at leisure, she reasoned, whereas to become a public woman was to risk being seen as a streetwalker.[49] Subsequent scholars have pushed against this sense of impossibility, however, by excavating the traces of the flâneuse in the work of George Sand and other novelists of the 19th century, and by reconstructing a genealogy of the female city walker in modernist fiction and film, from Virginia Woolf to the French New Wave and beyond.[50] In this body of work, the flâneuse has emerged as a vital means of capturing the shifting historical relationship between female subjectivity and the urban public realm, and Cléo remains her most enduring cinematic realisation.

If the figure of the woman walking and looking had become a potent cinematic symbol, it was not one without complexity, however. In Varda’s hands, Cléo readily embodies the feminist possibilities of the character type, but the sexual politics of male-directed films such as Godard’s Vivre sa vie or Antonioni’s La notte are more ambivalent. Such an inherent sense of duality is explored by Mark Betz in his in-depth reading of the “wandering women” of European art cinema. In the first instance, figures such as Florence (Jeanne Moreau) in Lift to the Scaffold or Claudia (Monica Vitti) in L’Avventura (1960) personify the modern femininity and liberated sexuality of the postwar decades, Betz suggests, but they equally register the uneasy dual status of the woman onscreen as both viewing subject and object-to-be-looked at. At the same time, Betz argues, the wandering woman became a resonant allegorical object, occupying the concurrent role of self (in relation to national culture) and Other (by gender) in the era of decolonization[51] . The wandering woman was therefore simultaneously a figure with feminist potential and a symbolic vehicle that expressed the contradictions of modernity, nationhood, and race in post-war France and Italy. Though the contexts of time and place are different, this sense of doubleness is critical for understanding the complexities of Eileen in Medium Cool.

How did this set of concerns translate to the United States in the late ’60s? As my discussion of cinematic predecessors suggests, “the woman in the yellow dress” can be traced back to multiple sources, yet Eileen differs in some significant ways from The Savage Eye‘s Judith McGuire and the wandering women of the European films. In the first instance, Eileen’s movements through the city are initially motivated by the search for her son, which makes her more anchored by familial bonds and less openly drifting than, for example, Lidia (Jeanne Moreau) in La notte. And unlike, say, Claudia in L’Avventura, Eileen isn’t the subject of a sexualized gaze, and her walking in the city is not compared to, or conflated with, the streetwalking of a prostitute. Eileen doesn’t fit the type of a ‘modern woman’ in the New Wave mould, in the sense of a liberated yet consumerist image of femininity. She’s an internal migrant from rural West Virginia, which is underlined both by intermittent flashbacks and Bloom’s articulation of her Appalachian accent, and, as a single mother, she’s routinely depicted within the domestic environment until the final scenes. Yet she’s typical and modern in other ways, as a kind of proletarianized white-collar worker in a low paid, but high-tech industry (she works for the electronics firm, Motorola; deleted scenes suggest at a plant that produces television sets). Like the female protagonists of the European New Waves, Eileen is therefore an ambivalent figure who embodies both tradition and modernity, self and other.

Mapping Chicago ’68

Though it’s difficult to argue for Eileen as an explicitly feminist figure in the mould of Cléo Victoire, she’s nevertheless central to the film politically. From one perspective, the act of walking itself is significant in the context of the American city, given the importance of the car to what Marshall Berman called the “expressway world” of post-war urbanism[52] . For characters to walk the streets at length, especially without a clear goal or destination, had the potential to challenge not only classical Hollywood dramaturgy but dominant ideologies of urbanism too. Filming the walking subject likewise embodies the camera with different sensations of mobility and vision to the rapid motion of driving and the panoramic view through the windshield. As James Tweedie argues in relation to the French New Wave, slowing the pace of cinema to match the rhythm of walking has radical potential. For Tweedie, the walking protagonists of the New Wave offered a counterpoint to the French city planners’ defining obsessions with speed, mobility, circulation, and flow – a critical stance that mirrored the Situationist practice of la dérive (‘drift’) and its rejection of accelerated urbanization and globalized media flows[53] . Such a dialogue between mobility and blockage, circulation and stasis equally defines Medium Cool, which is book-ended with imagery of crisis in Fordism and its automobile urbanism: the film memorably opens with a car wreck on the Eisenhower Expressway and finishes in symmetrical fashion with another brutal accident that kills Eileen and injures John. The sense of paralysis and stoppage established in the opening frames of the film is immediately reversed, however, by the evocative title sequence of the motorcycle courier approaching downtown Chicago with the reporters’ tapes, but as the film draws towards its climax, the media city is once more brought to a standstill by protestors, police lines, and tanks. Eileen’s walk draws power from its framing within these urban dynamics of stasis and motion, underlining the critical potential of the pedestrian and the view from the street in the mid-20th century city.

The walker is frequently figured as a detached observer, though, and distance is also crucial to Eileen’s relationship to the events of Chicago ’68 and how her role has been understood. One of the notable ambiguities of Medium Cool is that aside from a few brief vox pops early on, it does not provide an inside view into the white student radicals who made up the bulk of the protestors. Eileen lacks the cynical professionalism of John, but she is equally a distanced viewer, disconnected from the Movement by her migrant status, class background, and to some extent by gender. John, like Wexler, is at a generational remove from the baby boomers. He’s an ex-boxer, and this working-class machismo puts him at odds with the crowds in Grant Park, which are dominated by college students. Such distance also informs the use of Frank Zappa’s music at key moments of the film. Though Zappa is easily construed as part of the counterculture, his lyrics often skewered its conformity and commercialization, a sceptical perspective embodied by his publicly-expressed disdain for the demonstration as a means of political struggle[54] . Yet, despite Zappa’s acerbic lyrics about “phony hippies” in “Who Needs the Peace Corps,” a song such as “Mom & Dad” – which is used to create brooding tension as we watch the crowds swelling in the park – nevertheless has a strong sense of politically-charged reportage in its timely evocation of police violence (“the cops have shot some girls and boys”). In his approach to the DNC rallies, Wexler seems similarly split between an impulse to document social injustice and the nagging question of whether the protestors were too wrapped up in the media spectacle to challenge it effectively. The DNC scenes therefore play with a complex sense of alignment and distance: Eileen places the viewer simultaneously within the crowd yet outside of it, and the protest sequences are not simply straight reporting, but also a self-reflexive interrogation of their conditions of mediation.

The shifting interplay between character and environment that Eileen establishes is key to achieving this effect, and it’s therefore important that the TV cameraman should take a back seat at the film’s climax. Medium Cool‘s reflexive critique of the media requires the male reporter and his viewpoint to be disrupted. This decentring happens implicitly, and relatively gently, through Harold and his roving child’s eye view, and more forcefully when the black radicals challenge John, Gus, and the mass media apparatus they represent, but it is also central to the protest scenes, which are pointedly witnessed by Eileen, not the documentary crew. Moving between points of view is therefore central to the film’s political charge, in the sense that it attempts to map the multiple social forces of the ’60s in one city simultaneously. Such a strategy wasn’t always seen as successful: many of the film’s initial reviewers thought it lacked coherence and was overstuffed with hot-button topics. Penelope Gilliatt, for example, wrote that “Medium Cool is nothing if not on the nose, and truly loaded with issues – Vietnam and Appalachia and the child […] and McLuhan notions about the ‘cool’ medium of television, and Mayor Daley’s henchmen, and the nature of reality, and the vanishing sense of personal responsibility.”[55] The Hollywood Reporter reviewer likewise found watching the film akin to “spinning through all the TV channels at 6 o’clock in an effort to clarify the unrest of a generation”[56] , while the Motion Picture Exhibitor dismissed it as “merely a list” with “nothing to tie this list into a meaningful whole”[57] . But it’s exactly this attempt to capture the complexity of the moment, at the expense of linear narrative – the lack of an “integrated storyline”, as one reviewer put it – that defines its political aesthetics. The film is not formless or “merely a list”: it is structured by its Chicago setting, by a specific historical series of events, and by multiple viewpoints, each of which helps to build a picture of the whole. Such an iterative process of constructing a social “map” of Chicago chimes with Fredric Jameson’s concept of cognitive mapping and his call for politicized art to apprehend the “social totality” of late capitalism[58] . Medium Cool‘s objectives may perhaps be less grandiose but it nevertheless strives to interweave different areas of the city and multiple layers of the social world – from the domestic space of the apartment to the global reach of the television network cameras. Eileen and Harold are crucial components within this complex mosaic form in that they offer alternative ways of experiencing and viewing the city, and their separate journeys from the private and domestic space of the apartment to the public arena of the DNC protests, where “the whole world is watching”, stage an emblematic movement from the local scale of the urban neighbourhood to the nationally- and globally-networked space of downtown Chicago. When Eileen walks through the city in the final section of the film, it’s not a detour from John, then, but rather the capstone of the filmmakers’ social mapping of Chicago ’68, and her climactic confrontation with the military-industrial complex – where, to borrow the words of Chris Marker, “the state appears like a vision, like the Virgin Mary at Fátima” – is a moment charged with political significance[59] .

Deleted scenes, missed connections

Yet this scene is not conventionally viewed as a political awakening for Eileen, and to understand why it’s worth returning to the film’s editing and some of the macro-level decisions Wexler made about the final narrative. As I’ve suggested, the duality of the wandering woman is highly productive for unravelling some of the complexities of Medium Cool. While doubleness is therefore built into the figure of the female walker from the outset, in the specific case of Medium Cool an additional layer of narrative ambivalence and instability was introduced by the pressures of post-production – in particular, the need to edit the final cut of the film into a form ready to release as a Hollywood feature. As David James has argued, the sustained conflicts between Wexler and Paramount – a standoff between the possibilities of the underground and the constraints of studio filmmaking – are figured self-reflexively in the film’s narrative, especially in John’s struggle with the television station over its clandestine involvement with the FBI. In part, tensions over editing account for one of the film’s key unresolved questions: why do the final sequences focus on Eileen in the first place? If the film’s conventional narrative arc tracks John’s move from professional objectivity to political consciousness, why place such weight on Eileen only at the end? And are we encouraged to read Eileen as making a similar transformation? After all, in the European films, the walk of the flâneuse is often an explicit moment of self-reflection and epiphany. Yet audiences have not tended to read Eileen’s walk as a moment of political awakening, despite such apparent cues. As I’ve suggested, this is partly a matter of the interpretive frames created by the film’s marketing and reception, but it is also a result of what happens – or rather what does not happen – in the earlier sections of the film. One of the many insights offered by the indispensable six-hour extended cut of Paul Cronin’s documentary, Look Out Haskell, It’s Real: The Making of ‘Medium Cool‘ (2001), is that a major subplot containing Eileen was filmed and later removed from the final version of Medium Cool [60] . In these scenes, Eileen spends time with Peggy Terry, a real-life community activist working in the Uptown area, and becomes involved in local political organising. One pivotal deleted scene shows Eileen and Terry making connections with African-American groups and attending a speech by the Civil Rights leader Jesse Jackson, who at that point was promoting ideas of class solidarity across racial divides in Chicago. Although we shouldn’t place too much weight on this material (which has never been seen by audiences outside of Cronin’s documentary) as a means to understand the film as released, it does provide a sense of the potential and the limits embodied by the character of Eileen.

Several conclusions can be drawn from these scenes and their omission from the final cut. First, it’s clear that Eileen was originally intended to be a much more substantial character throughout, and that her central presence in the protest sequences was designed to be prefigured by extensive character development earlier in the film. Secondly, the deleted scenes of Eileen and Terry suggests that Eileen’s narrative arc was explicitly intended as one of political awakening, which would have functioned in parallel to John’s transformation from objective professionalism to political self-awareness. Such a dual emphasis might have made the protest sequences the climax to both characters’ journey to political commitment, as well as being motivated by the search for Harold, which ties up the secondary familial (and romantic) strand of the narrative. Finally, removing these scenes not only pushes the audience away from identifying Eileen as an explicitly feminist character, but also weakens the themes of cross-racial solidarity that the film engages with elsewhere but never fully reconciles in the released cut.

Moving across class and race boundaries in Chicago allows Medium Cool to gesture towards radical connections between feminism, black power, and student politics in ways that are present but ultimately subdued in the final version[61] . Eileen’s position in this respect is complex: she is marked as an outsider by her status as an Appalachian migrant and her strong West Virginia accent, yet the ease with which Bloom passes through the city streets and across police barriers is implicitly enabled by her whiteness, as was the camera crew’s fluid movement through the crowds. Furthermore, as Betz suggests, the whiteness of the wandering woman was not an incidental feature of the character type. For Betz, decolonization was one crucial overarching context for this cinematic figure in the European films, though, as he deftly illustrates, such concerns are often made subtly visible (or audible) to the audience by what superficially seem like peripheral details, such as the persistent background presence of radio reports about the Algerian War in Cléo from 5 to 7 [62] . European colonialism might not initially present a natural point of reference for American cinema at the end of the 1960s, but if the United States was not undergoing overseas decolonization, it was undoubtedly mired in what was widely decried as an imperialist war in Vietnam. Such a threat to American hegemony abroad was matched by the escalating crisis in the African-American inner cities, where racial injustice and “internal colonization” was being fiercely challenged by the Black Panthers and other radical groups such as the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit [63] . In other words, though the conflicts and stakes were distinct from European decolonization, the US was nevertheless experiencing anti-colonial struggle.

Both Vietnam and the revolutionary stirrings of the inner cities are deeply embedded in Medium Cool. Like the Algerian War in Cléo, Vietnam is not directly shown yet is always present as a kind of low-level background buzz. Beyond being the primary focal point for the protests, the war is mentioned by Harold: his father is either serving in Vietnam, or has died there; alternatively, neither of these might be true, as Eileen suggests. In John’s apartment we glimpse perhaps the most famous photograph of the entire conflict – Eddie Adams’s Pulitzer Prize-winning image of the execution of a Vietcong soldier, Nguyen Van Lém – as well as black-and-white stills of his own stint as a war correspondent in South East Asia. The racial fault-lines of Chicago are more directly confronted, especially in the pivotal scene where John and Gus visit the black radicals in the South Side, which, as Stephen Charbonneau examines in his article in this dossier, offers an incisive and self-questioning commentary on the city’s de facto segregation and the power relations at play when a white camera crew films in a black neighbourhood. The compelling scene in the South Side apartment arguably does more than any Hollywood film of the time to confront both the racial politics of America’s urban crisis and the media’s complicity with it. Nevertheless, the film drew criticism, most notably from Andrew Sarris, for focusing on the well-publicized Chicago events over and above the more lethal rioting and police repression of African-Americans at the Republican National Convention in Miami that August. As Sarris wrote in his spiky and combative review for The Village Voice, “seven blacks in Miami were slain during the convention that nominated Richard Nixon but there were no photographers present, no upper-middle-class white demonstrators, no cultural emissaries from Esquire and the Playboy Club.” “I have already seen several films on Chicago in 1968”, Sarris wrote, “but I don’t ever expect to see any on the murders in Miami”.[64] For Sarris, Medium Cool risked amplifying the profound racial inequalities of media coverage that the South Side scenes sought to tackle, while the protest footage itself ended up as “curiously ambiguous” in comparison to the coverage on television. In this context, the figure of the (white) woman walking embodies the split between Sarris’s assessment of the film as a “band-aid of broken-headed liberalism” and its radical potential; one would have to look to an underground film such as Haile Gerima’s Bush Mama (1979) and its protagonist, Dorothy, for direct engagement between the wandering woman and racial oppression in the American city[65] .

Medium Cool and New Hollywood historiography

To conclude, I want to briefly reflect on how we might rethink Medium Cool in relation to the historiography of New Hollywood. Viewing Eileen as a “wandering woman” reveals complex linkages between Medium Cool, European art cinema, and the New American Cinema of the early 1960s. But connections can be traced within the New Hollywood too, and if Medium Cool is often grouped with other groundbreaking features of the same year, such as Easy Rider (1969) and Midnight Cowboy (1969), it can equally be aligned with another cluster of films that foreground the wandering female protagonist rather than the critically-celebrated male anti-hero. Consider, for example, Francis Ford Coppola’s female-led road movie The Rain People (1969), which was released on the same day as Medium Cool. As Hollis Alpert noted in the Saturday Review, there were revealing similarities between the two films, especially in the filmmakers’ shared choice to leave “the studio behind them to find and tell their stories against actual backgrounds, often using what they discover to flesh out their films”. [66] But this documentary-inflected approach to location was also crucially linked thematically by their female characters. In The Rain People, Shirley Knight plays Natalie Ravenna, described by Alpert as “a discontented housewife who leaves her Long Island home and husband in search for herself on the nation’s road and turnpikes”[67] . Her flight from the family is amplified by the filmmakers’ resonant use of rural and small-town locations, especially through extended sequences that elevate landscape and the process of looking over dialogue and narrative development in a way that also suggests the influence of European cinema and the figure of the wandering woman. In The Rain People and other films of the early 1970s – including Wanda (Barbara Loden, 1970), Desperate Characters (Frank D. Gilroy, 1971), and A Woman Under the Influence (John Cassavetes, 1974) – the female walker expressed a growing sense of disconnection from the patriarchal structures of family and domesticity [68] . Molly Haskell was among the first to diagnose this small but significant counter-trend of “neo-women’s films” and what she saw as “a new kind of heroine modelled on the French and Italian art cinema and its image of the “discontented, spiritually and/or sexually hungry woman, often adrift in a world from which she feels estranged.”[69] From a critical standpoint, these drifting protagonists offer a female counterpart to the widely-discussed figure of the “unmotivated hero”, who was always implicitly male, at least in the range of examples in Thomas Elsaesser’s original 1975 essay (the New Yorker critic David Denby summed up the type succinctly around the same time: this was “a cinema of male dithering”) [70] . Industrially, the neo-woman’s films that Haskell describes embodied the possibilities and constraints of the New Hollywood for women, while at a broader social level they registered the surge in the women’s movement and its challenge to the gendered division of labour that had underpinned the post-war economy.While there’s certainly some distance between Medium Cool‘s Eileen and the drifting heroines that Haskell writes about, it’s nevertheless productive to position her within a lineage of female protagonists that stretches back through The Savage Eye to post-war European art cinema.

In this piece, I’ve built on scholarship that has begun to revise our understanding of New Hollywood, especially through recovering the marginalized work of female directors and practitioners [71] . As my analysis shows, critical historiography of New Hollywood needs to reckon with the extent to which masculinist paradigms – especially, but not only, auteurism – have shaped how we view films, how we study their production and reception histories, and how we attribute authorship and creative input. My intention here has not been to recover Medium Cool as a feminist text but rather to throw light on the processes by which the film’s female protagonist – and its female post-production team – have been rendered invisible by gendered critical frameworks.

As my analysis suggests, Eileen is a vital yet complex component of Medium Cool. Rather than seeing her as a “tour guide” who dissolves into the background, I’ve argued that she plays a central role in the film – a role that engages a wider cultural history of the female walker onscreen, with all its political possibilities and ambivalences. In the first instance, Verna Bloom’s performance and her movement through the crowd make the protest scenes possible: they orient the viewer and help to create a personalized, human framing of the Chicago ’68 riots – events that by the time of the film’s release, had already become overfamiliar media images for the public. Drawing on the multivalent motif of the female walker – a character type that had already gained momentum – the filmmakers used the detached but embodied mobile gaze to create a productive tension between documentary and fiction. Eileen’s journey through the protests is the climax of the film’s social mapping of Chicago ’68, but its intended status as a political epiphany for the character was undoubtedly undermined by the removal of key scenes from the film, as well as by persistent frames of promotion and reception that have tended to amplify an auteurist approach to the film and its production history. Despite her critical status as a secondary character, Eileen is central to Medium Cool formally and ideologically, but, as I’ve shown, the figure of the “Woman in the Yellow Dress” personifies the instability of the film’s production process and the political pressures of the 1960s more generally. As a cinematic type, the female walker embodies the potential opened up by shifting industrial and cultural contexts, but equally crystallizes some of the missed connections between Hollywood cinema, second-wave feminism, and the radical politics of 1968 [72] . Fifty years after the release of Medium Cool, such tensions and contradictions are an unresolvable part of the film’s rich legacy and evidence of its paradoxical position between Hollywood and the underground.

This article is dedicated to Verna Bloom, who died in January 2019.

Notes:

[1] Because the characters are referred to only as John, Eileen, and Harold in the credits, I will use their first names rather than surnames in this article.

[2] Herb A. Lightman, “The Filming of Medium Cool“, American Cinematographer, January 1970, p. 25.

[3] Ibid. Discussing the cut sequence, Wexler explained: “Cameramen always get excited about a challenging shot like this, but they find out that it doesn’t mean a damned thing to the people who go to the theatre”.

[4] For an in-depth discussion of the background to the Chicago events, see Jon Lewis, “Slouching Toward Chicago in Search of Peace and Love: Medium Cool and Chicago 1968″, in Architectures of Revolt: The Cinematic City Circa 1968, ed. Mark Shiel (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2018), pp. 112-130.

[5] Michael Renov, The Subject of Documentary (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), p. 21.

[6] Renov, p. 28.

[7] Renov, p. 33.

[8] Renov, p. 34.

[9] Joseph Morgenstern, “Movies: American Images”, Newsweek, September 1 1969, p. 68.

[10] Mark Betz, Beyond the Subtitle: Remapping European Art Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), pp. 93-177.

[11] The phrase “promotional surround” draws on Barbara Klinger’s work on historical reception. See Barbara Klinger, “Film History Terminable and Interminable: Recovering the Past in Reception Studies”, Screen 38, no. 2 (Summer 1997), pp. 107-128.

[12] Medium Cool publicity, Paramount (1969), British Film Institute Library.

[13] Richard Corliss, “Haskell Wexler’s radical education”, Film Quarterly 23, no.2, p. 53.

[14] “Housewife” is used in Mandel Herbstman, “Medium Cool”, Film and TV Daily, July 25 1969, clippings file, Margaret Herrick Library; “the love interest” is from John Mahoney, “Paramount’s Medium Cool Not That, But Not So Hot”, Hollywood Reporter, July 24 1969, clippings file, Margaret Herrick Library.

[15] Bill, “Medium Cool”, Motion Picture Exhibitor, July 23 1969, clippings file, Margaret Herrick Library.

[16] Medium Cool publicity. The same text appears in Lightman, p. 23 (published in January 1970).

[17] Lightman, p. 23.

[18] Gordon Gow, “Medium Cool”, Films and Filming, April 1970, clippings file, Margaret Herrick Library.

[19] Lightman, p. 23.

[20] Ernest Callenbach and Albert Johnson, “The Danger is Seduction: An Interview with Haskell Wexler”, Film Quarterly 21, no. 3 (Spring, 1968), p. 11.

[21] Pauline Kael, “Circles and Squares”, Film Quarterly 16, no. 3 (Spring 1963): p. 26. Kael attacked Sarris and other auteurist critics for their “peculiar emphasis on virility” and noted the essentially masculine nature of the auteurist model (“If there any female practitioners of auteur criticism, I have not yet discovered them”) (p. 26). For a feminist critique of auteurism, see Geneviève Sellier, Masculine Singular: French New Wave Cinema, trans. Kristin Ross (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008).

[22] As a representative sample: David E. James, Allegories of Cinema: American Film in the Sixties (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989) and Renov (2004), as well as more recent texts: Jonathan Kirshner, Hollywood’s Last Golden Age: Politics, Society, and the Seventies Film in America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012), pp. 56-61; Jon Lewis, “Slouching Toward Chicago in Search of Peace and Love: Medium Cool and Chicago 1968″, in Architectures of Revolt: The Cinematic City Circa 1968, ed. Mark Shiel (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2018), 112-130; and Oliver Gruner, “‘About As Brutal, Relevant and Exploitable as They Come’: Medium Cool (1969) and Political Filmmaking”, in The Hollywood Renaissance: Revisiting American Cinema’s Most Celebrated Era, ed. Peter Krämer and Yannis Tzioumakis (London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), pp. 91-110.

[23] Erin Hill, Never Done: A History of Women’s Work in Media Production (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2016).

[24] Maya Montañez Smukler, Liberating Hollywood: Women Directors and the Feminist Reform of 1970s American Cinema (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2019).

[25] Leslie Hill, “Verna Fields never wanted a career”, Cinema 35 (1976), pp. 30-32.

[26] Paul Rosenfield, “Women in Hollywood”, Los Angeles Times, July 13, 1982, G1.

[27] Hill, 32. See also Benjamin Wright, “The Auteur Renaissance, 1968-1980: Editing”, in Editing and Special/Visual Effects, edited by Charlie Keil and Kristen Whissel (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2016), p. 112.

[28] Anonymous, “Dialogue on Film: Verna Fields”, American Film, vol. 1, no.8, Jun 1, 1976, p. 45.

[29] Howard Thompson, “The Local Film Front”, The New York Times, August 23, 1959, X5.

[30] John McCarten, “The Savage Eye”, The New Yorker, June 18, 1960. Maddow’s first draft of the script dates to 1952, though the film did not move into production until several years later. Margaret Herrick Library, Jack Couffer papers.

[31] Following plaudits at the Venice and Edinburgh film festivals, it was reviewed relatively widely and enjoyed not insubstantial distribution for an independent feature. See “Savage Eye Wins Award at Edinburgh”, Variety, September 16, 1959, 7; “Distribs Share Indie Film”, Variety, February 10, 1960, p. 21.

[32] Jack Couffer, The Lion and The Giraffe: A Naturalist’s Life in the Movie Business (BearManor Media, 2010).

[33] Jan-Christopher Horak, “Seeing With One’s Own Eyes: Helen Levitt’s Films,” The Yale Journal of Criticism 8, no. 2 (1995): p. 80.

[34] Horak, p. 80.

[35] On cinematography in the 1960s, see Bradley Schauer, “The Auteur Renaissance, 1968-1980”, in Cinematography, ed. Patrick Keating (Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2014), pp. 84-105.

[36] Lewis, p. 116.

[37] On the imperial nature of the 1893 World’s Exposition, see Mona Domosh, “A ‘Civilized’ Commerce: Gender, ‘Race’, and Empire at the 1893 Chicago Exposition”, Cultural Geographies 9, no. 2 (2009): 181-201.

[38] David Culbert, “Television’s Visual Impact on Decision-Making in the USA, 1968: The Tet Offensive and Chicago’s Democratic National Convention”, Journal of Contemporary History 33, no. 3 (July 1998), p. 438.

[39] A controversial Gallup poll suggested that “televised images of violence simply strengthened popular support for police authority in America”, and as Melvin Small observed, “Many television viewers witnessing violence between ‘hippies’ and police instinctively sided with the police, no matter what they saw on their screen”. Culbert, p. 447.

[40] Lightman, p. 23.

[41] Lewis, p. 117.

[42] Andrew Sarris, “Films”, Village Voice, August 28 1969, 37; “New Movies: Dynamite”, Time, 22 August 1969, p. 62, clippings file, Margaret Herrick Library.

[43] Jerry Beigel, “‘Medium Cool’ From Chicago”, Variety, December 11 1968, p. 7.

[44] William Wolf, “New Films”, Cue, 30 August 1969, clippings file, Margaret Herrick Library; Joseph Morgenstern, “Movies: American Images”, Newsweek, 1 September 1969, 68.

[45] Medium Cool’s Harold is also arguably modelled on another character type from postwar European art film: the child adrift in the city, visible in films such as Germany Year Zero (Roberto Rossellini, 1948) and The 400 Blows (François Truffaut, 1959).

[46] Sandy Flitterman-Lewis, To Desire Differently: Feminism and the French Cinema (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1990), pp. 268-284.

[47] Janice Mouton, “From Feminine Masquerade to Flaneuse: Agnès Varda’s Cléo in the City”, Cinema Journal 40, no. 2 (Winter 2001): pp. 3-16.

[48] Elizabeth Wilson, “The Invisible Flâneur”, New Left Review191 (1992): p. 93.

[49] Janet Wolff, “The Invisible Flâneuse: Women and the Literature of Modernity”, Theory, Culture and Society 2, no. 3 (1985): pp. 37-46.

[50] See, for example, Wilson (1992); Deborah Parsons, Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City and Modernity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000); Mouton (2001); Jill Forbes, “Gender and Space in Cléo de 5 à 7“, Studies in French Cinema 2, no. 2 (2002): pp. 83-89. Lauren Elkin has more recently popularized the term in her book of the same name and argued for its contemporary relevance. See Elkin, Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London (London: Chatto and Windus, 2016).