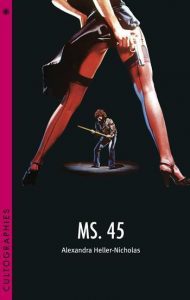

| Alexandra Heller-Nicholas MS .45 (Cultographies series) Columbia University Press/Wallflower, 2017 ISBN: 9780231851053 Au$28.99 (pb) 156pp (Review copy supplied by Columbia University Press) |

|

Alexander Heller-Nicholas begins her scholarly and engaging book on MS .45 with the compelling claim, that “few films have left quite the same cultural imprint as Abel Ferrara’s 1981 film MS .45”. (p. 1) She then proceeds to detail what this means, unpacking the origins, nature and legacies of MS .45’s significant “cultural imprint”.

MS .45 was directed by the mercurial Abel Ferrara and stars the sublime Zoe Tamerlis Lund in the lead role of a mute woman Thana, a fashion-industry worker, who is raped twice in one day and sets out on a trajectory of vengeance. MS .45 is a film that has been, and continues to be, loved by diverse audiences – from fans of exploitation and rape-revenge films to Abel Ferrara and Zoe Tamerlis Lund art-house cinephiles. It is also a film that has been lost and found, originally being watched in grindhouse cinemas in the early 1980s, quickly disappearing and then circulating in underground ways in various VHS tape versions until it was reissued by Drafthouse films in 2013, theatrically as well as on DVD.

Heller-Nicholas’s book on MS .45 is part of the Cultographies series that follow in the tradition of books on a single film that began, in a sustained way, with the BFI classics series. The Cultographies books focus on individual cult films, with a particular interest in reception. Some of the books in the series include Deep Red by Alexia Kannas (2017), Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! By Dean DiFino (2014), Bad Taste by Jim Barratt (2009), The Evil Dead by Kate Egan (2011), Blade Runner by Matt Hills (2011) and They Live by D. Harlan Wilson (2014), each book providing a detailed study of an important, often marginalized cult film.

Heller-Nicholas is well positioned to be writing on MS .45 as she is a key film scholar on cult, horror and exploitation cinema and has written several important books that include Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study (McFarland, 2011) Found Footage Horror Films: Fear and The Appearance of Reality (McFarland, 2014), Suspiria (Devil’s Advocates, 2015), The Hitcher (Arrow, 2018) and MS .45 (Columbia University Press, 2017). She is also a prolific and widely published cinema scholar who has written hundreds of reviews, essays and book chapters, often turning her attention to marginalized films such as Pulp (Hodges, 1972) and A New Leaf (May, 1971). Most recently she has contributed an audio commentary, together with film scholar Lee Gambin, for Arrow’s blu-ray release of another important cult film Carrie (De Palma, 1976).

MS .45 builds on Heller-Nicholas’s important work on the challenging and often marginalized sub-genre of rape-revenge films that have received minor scholarly attention. While she does discuss MS .45 in her previous book Rape-Revenge Films: A Critical Study, she describes this new book as “a refinement, a drilling-down into one of the most important rape-revenge films ever made” (P. 18-19). This “drilling down” is precisely what she does, looking closely, in detail, at a film that is not just a rape-revenge film but also a feminist cult film – a potent combination. In fact, one of the key questions that Heller-Nicholas explores in this book is how MS .45’s reputation has shifted from being a critically marginalized rape-revenge film to an important feminist cult film.

The book features an Introduction and four chapters. The Introduction frames the book’s project and MS .45’s status as a cult film. The first chapter explores how this film came to be made in the early 1980s, looking at multiple histories and contexts, and providing insight into the key figures of the director Abel Ferrara and the actress Zoe Tamerlis Lund, their creative relationship, the extended crew of collaborators, and the role that the city of New York played in the film’s making. The second chapter burrows into the film, undertaking a close reading that is divided into three sections that follows Thana’s story with narrative sub-headings of ‘Rape’, ‘Revenge’ and ‘Resolution?’. Chapter three details the promotion, distribution and the reception of the film on its initial release, the battles with censorship, and the impact of Ferrara’s association with the Video Nasties controversy in the UK. The final chapter discusses MS .45’s legacies and its importance to contemporary audiences, in particular “women’s cult film fandom”.

Extensive research informs this book. Heller-Nicholas’s interest in the complex reception history of this film covers a wide range of scholars, creative practitioners and fan activity. She references key feminist scholars and their seminal books – Barbara Creed’s Monstrous Feminine (1993) and Carol Clover’s Men, Women and Chainsaws (1992). She also acknowledges the “foundational” scholarly work on Abel Ferrara that has been undertaken by Brad Stevens, Nicole Brenez and Adrian Martin, as well as many interviews with Ferrara, Tamerlis Lund and their collaborators. Heller Nicholas also examines the recent writing and responses of scholars, film critics and women who are part of the subculture of “rape-revenge film fandom”.

This is also a book informed by Heller-Nicholas’s own considerable knowledge of, and passion for, the cinema. One of the pleasures in reading the book can be found in the multiple links and references to other films that are made throughout the analysis, including films that inspired or were referenced in MS .45 such as Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976), Michael Winner’s Death Wish (1974) and Roman Polanski’s Repulsion, further comparisons with Ferrara’s own oeuvre with particular attention to The Driller Killer (1979) and Bad Lieutenant (1992), and broader connections to films with “mute women rape-revenge protagonists” that include Johnny Belinda (1948) and The Spiral Staircase (1945), to mention just a few of the wider tapestry of films that are part of the exploration of this individual film.

Heller Nicholas’s love for MS .45 and Zoe Tamerlis Lund is at the heart of her analysis and enlivens her vibrant voice. She has her own origins story with this film that she describes in her introduction. She talks about watching MS .45 “on the rickety old VCR in the student house” she lived in when she took her “first tentative steps in the world as a young woman at university, in the mid-1980s”. (p. 18) She goes on to describe studying the film “when a male lecturer screened MS .45 in an undergraduate course”. (p. 18) This leads her to the reflection that “what Thana taught me most of all was that the men who introduced me to the movie were a real part of the evolution of my own lived experience as a woman and my own relationship to the word ‘feminism’” (p. 19) Later in the book, reflecting on MS .45 and the topic of “rape-revenge film fandom” she says that “through MS .45, I learnt how to carve a niche for my own pleasures in what I assumed to be boys-only terrain.” (P.117)

It is this combination of the scholarly and personal, the gravity and also the pleasures that Heller-Nicholas finds in the rape-revenge genre and MS .45 in particular, her contextualizing of this film in the wider debates about feminism and gender in the 1980s when this film was made as well as the decades that followed, and Heller Nicholas’s quite particular ability to share her passions with her readers that makes this a very readable and important book.

Anna Dzenis

La Trobe University, Australia.