In 2004 Matt Groening, the chief creator of the television series The Simpsons, published an eclectic list of his “100 Favourite Things”. High on the inventory were two films by Stanley Kubrick, placed equally at number 16: Lolita (1962) and Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1963, herein referred to as Dr. Strangelove). [1] Groening’s admiration for the cinema of Kubrick is well documented, despite being dismissively described by one critic as a “man crush”, and one shared amongst many of the animated television program’s creative team. [2] For example, The Simpsons’ showrunner and executive producer, David Mirkin, has noted that Kubrick was a primary career inspiration and one of the “main reasons” he aspired to become a director. [3] The appeal to Groening and his collaborators should be obvious. Kubrick was one of the few consistently subversive and satirical post-WWII screen producers capable of remaining independent while financial attractive and ostensibly working ‘within’ the Hollywood studio system.

There are far too many references to Kubrick’s work in The Simpsons to do justice comprehensively to their allusions in this essay. [4] What follows is a broad, representative sample with some close textual readings of the key cinematic influences observable in The Simpsons. [5]

Satire, Parody, Homage

Kubrick’s early meditations on the absurdities of modern life foregrounded comedy and satire as entirely apposite for cinematic expression. On note cards and in a hand-written letter (circa 1961-62) he commends the power of satiric tradition from the ancient Juvenal to Enlightenment Swift. [6] By the early 1960s Kubrick was despondent with the lack of the ‘comic spirit’ evident in the latter half of the twentieth century:

The serious writers of the 20th century have taken themselves too seriously. The comic spirit has been lacking; comic vision of life … If the modern world could be summed up in a single word it would be absurd. The only truly creative response to this is the comic vision of life. [7]

In his background research for Dr. Strangelove Kubrick explicitly noted one of his motivations was to “be heretical” and to satirise government. [8] The filmmaker presented this approach eloquently to John Hofsess at the time of the release of A Clockwork Orange (1971):

A satirist is someone who has a very skeptical, pessimistic view of human nature, but who still has the optimism to make some sort of a joke out of it. However brutal the joke might be. [9]

Kubrick’s penchant for sardonic humor was apparent long before his notable double-entendres in Lolita (1962) and his dark masterpiece Dr. Strangelove. It is evident in aspects of his mise en scène, including ironic in-situ signage such as “No Exit” seen before a murder in an alleyway or “Watch your step” above a staircase, both in Killer’s Kiss (Stanley Kubrick, 1955). Such allusive compositions remained a constant throughout Kubrick’s oeuvre including the “Lucky to Be Alive” headline at a Greenwich Village newsstand, the latter self-referentially gesturing to Kubrick’s first commercial photo sale as a teenager in 1945 to Look magazine. [10]

Robert Stam has asserted that the antecedents of Kubrick’s satirical technique dates back to the classics of the genre, suggesting Kubrick’s style moves beyond the gentility of carnivalesque parody to “angry satire” that deploys “exaggeration to prove a point”. [11] True to satiric tradition Stam affirms that in Dr. Strangelove “virtually all of the characters have improbably allegorical names redolent of sexual passion and aggression”. [12] However, Stam’s observations apply equally to Kubrick’s other character nomenclature in Lolita, A Clockwork Orange, Full Metal Jacket (1987), and to a lesser extent, Barry Lyndon (1975).

Similarly The Simpsons is seen by many commentators as the perfect mixture of subversion and humor, blending “shock and reassurance” recalling the “carnivalesque” in its capacity “to explore darker, subversive aspects of family life thanks mainly to the possibilities of the cartoon aesthetic”. [13] Matt Groening has repeatedly expressed his desire that The Simpsons be “political, satirical and subversive”. [14] Twenty years on from the show’s debut he told CNN: “I don’t know how subversive you can be when you’ve been on the air as long as we have. But we try to sneak some stuff in here and there, and gladden the hearts of sensitive viewers”. [15] Indeed, as Groening’s ex-wife has noted, the comic book artist embraced the creative tactic of being “sneakily subversive”, with “a kind of cynicism … that’s idealistic without being naïve”. [16]

By simultaneously working within the studio system but remaining outside of it – yet still producing provocative, singular artistic visions (in collaborating with others) – Kubrick’s professional example was surely inspiring to Groening and his team. For example, writer-director-animator, Brad Bird (The Iron Giant [1999], The Incredibles [2004], Ratatouille [2007], Tomorrowland [2015]) served as an executive consultant for The Simpsons during its first eight seasons as well as being an occasional director. Bird is credited with helping adapt the animation style from Groening’s crude one-minute drawings on The Tracey Ullman Show (1987-89) to the 30-minute sequences for the Fox network. Bird is proud that The Simpsons educates and entertains it audience by encouraging them:

to know more about the world around them … [It] refers not just to the pop hit from the last two or three years, but Kubrick films and Orson Welles. It gets into jokes about Russian literature and encourages you to go out and know more about the world and experience more in terms of art and culture. [17]

As John Ortved has outlined early Simpsons episodes “riffed” off classic theatre and film tropes, where the series writers were “uninhibited” in their more “blatant references” to filmmakers such as Stanley Kubrick, whom Ortved cites as “a recurring favourite”. [18] However, The Simpsons’ engagement with the Kubrick oeuvre is far from pastiche in either the classical or postmodern definition. There is nothing that is “empty” or “blank” about the parodic referencing of key Kubrickean scenes in the television series. The series’ creators and writers are keenly aware of their own formal (i.e. televisual, sitcom and animated) approaches to the content and its varied expression, moving beyond the literary and artistic tradition of pastiche as a means of mere imitation, towards homage, irony and satire.

The Simpsons’ Kubrick

The Simpsons mini-episode anthology format named “Treehouse of Horror” comprises the annual Halloween special and regularly serves to parody, satirise and pay homage to exemplary and popular cinematic and literary works. By 1994 “Treehouse of Horror V” (Season 6, Episode 6) contained the most sustained Kubrick homage of the period. One of the three short sub-episodes is titled “The Shinning”’, unambiguously inspired by The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980). When Bart utters the word “shining” to refer to his mental telepathy, Groundskeeper Willie fears the term will augur legal action due to copyright violation. [19] He cautions: “Ssshhhh … do you wanna get sued?” promptly suggesting Bart adopts “shinning” as a safer alternative. This comic aside is both ironic and historically accurate. The implied threat may stem from legal precedent as much as the perception that either/both filmmaker Stanley Kubrick and/or author Stephen King were notoriously litigious. Perhaps the most famous of Kubrick’s legal battles was the suit for plagiarism launched with writer Peter George during the production of Dr. Strangelove against the authors of Fail-Safe. [20] Amongst others Kubrick threatened legal action against were the producers of The Loved One (1965), Terry Southern for Blue Movie, the producers of The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies (Ray Dennis Steckler, 1964) and the creators of Space 1999 (Gerry and Sylvia Anderson, 1975-77) due to the respective title similarity with Dr. Strangelove and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). [21] Kubrick was also on the receiving end of legal challenges, including the successful claim by composer György Ligeti over the rights to his music being used on the 2001 film soundtrack. [22] Similarly, Stephen King sued New Line Cinema over The Lawnmower Man (Brett Leonard, 1992) and was himself sued by Anne Hiltner, allegedly the real-life the character played by Kathy Bates as a sadistic nurse in Misery (Rob Reiner, 1990). [23]

In “The Shinning” when the Simpsons family traverse an enormous resort hotel, escorted by billionaire Montgomery Burns (who describes the site as being built on Indian burial grounds and subject to satanic rituals), they pause to watch a wave of blood pour out from nearby elevators and wash past them at knee height. Burns drolly explains that the blood “normally gets off” at another floor, a comment that softens the visual impact of the sequence. [24] However, the animated tracking shot that immediately precedes the elevator’s purging has little to do with replicating The Shining’s interior. Indeed, if anything, it imitates any number of gothic haunted castles and mansions familiar from 1940s-50s Universal Studios and 1960s American International Pictures horror features. Along the walls are mounted suits of armour and a huge array of blades, battleaxes, spears, clubs and swords. However, the reverse cutaway to the elevator reveals a complex verisimilitude with The Shining’s production design and décor. Although the colour scheme is entirely different, the framing and textures are remarkably similar, from the checkered upholstery of the armchair to the semi-circular lift dials and the metal ornamentation surrounding the twin doors. This attention to detail signifies not only an act of homage but perhaps a necessary level of intertextual association, explication and cognitive immersion that Burns’ joke requires for viewer recognition and appreciation. [25] Hence, the scene and wisecrack serves to narratively satisfy both the Kubrick aficionado and audiences unfamiliar with The Shining.

For parody to work an audience must be au fait with the underlying source material. Umberto Eco identifies the phenomenon of intertextual parody as implicitly creating a “dialogue” in which a given text echoes the previous text. Eco notes that such texts quoted in other texts assumes a “taken for granted” knowledge of the preceding referent in order to appreciate its connotation in the new text. [26] Audience enjoyment stems from recognition of the topoi contained within the viewers’ encyclopedic “treasury of collective imagination”. [27] This implies that mass entertainment necessitates familiarity with such quotation and/or understandings of a structural or thematic topos (e.g. a Hollywood happy ending), as much as iconography or generic formulae. If The Simpsons’ frequent movie references cited more obscure, though nevertheless lauded films and filmmakers – say, Sergei Parajanov’s The Colour of Pomegranates (1969) or Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966) – audience recognition would diminish and the pleasure of cinematic allusion only reward the cognoscenti.

However, these topologically familiar themes, characters, plotlines and dialogue are simply not enough to satisfy The Simpsons team. Their Kubrickean allusions extend into the formal and textual construction of the animation process itself. Animator and series consultant Brad Bird has described how he helped change the conventional animation storyboard ‘culture’ that was operating in the series’ early seasons. When confronted with tame and pedestrian visual concepts for this particular episode Bird rebelled, admonishing (while encouraging) his artist(s):

No, come on, man! We’re doing a take on The Shining here. Let’s look at how Kubrick uses his camera. His camera always has wide-angle lenses. Oftentimes, the compositions are symmetrical. Let’s do a drawing that simulates a wide-angle lens. They’re deep focus. Let’s push things off and play on that. [28]

The result was stunning. For instance, when Marge mirrors the action of wide-eyed Wendy Torrance (Shelley Duvall) – who stumbles on the obsessive and manic repetition of her husband’s typescript, repeating “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” – Marge articulates expositionally what viewers familiar with The Shining will anticipate, while simultaneously telegraphing plot and motivation to the uninitiated: “What he’s typed will be a window into his madness”. A grimacing Marge approaches Homer’s empty desk to view a page embedded in the typewriter. It reveals: “Feelin’ fine”. The editing matches Wendy Torrance’s scene but unlike Kubrick’s naturalistic lighting The Simpsons’ colour palette is drenched in dark blues and purples with a correspondingly menacing, high-pitched Ligeti-style string score. Momentarily relieved, Marge has her doubts promptly reconfirmed with a flash of lightning that displays Homer’s crazed screeds of text (à la The Shining), not on typed manuscript, but covering the hotel’s cavernous central lobby space. Homer’s demented graffiti: “NO TV AND NO BEER MAKE HOMER GO CRAZY” is scribbled in enormous black and blue capital letters across walls, staircases, pillars, artworks, upholstery, carpets and ceilings. [29] Rapid cutaways render Marge’s horrified point-of-view as lightning flashes and thunder rolls. An animated, semi-circular dolly track serves to rotate the space in front of Marge’s eyes (and ours), displaying the scope of Homer’s psychosis. Unlike the comic book fidelity of MAD magazine spoofs of Hollywood features, ‘The Shinning’ sequence from The Simpsons’ “Treehouse of Horror V” transcends its referent in surprising ways, becoming a meta-homage.

The Halloween parody continues with Homer chopping away at an interior door using a large fire axe. He shoves his face through the open panel and reprises Jack Torrance’s (Jack Nicholson) infamous line: “Heeeere’s Johnny!” – however, a rapid reverse zoom reveals it is the wrong room: “D’oh!” With his next attempt, Homer pokes his crazed face through the door yelling: “Daaaavid Letterman!” only to find Grandpa (Abe) Simpson waving hello in his dementia, not recognising Homer. The final axe attack hits the mark as an increasingly maniacal Homer thrusts a stopwatch through the opening: “I’m Mike Wallace, I’m Morley Safer, and I’m Ed Bradley. All this and Andy Rooney, tonight on 60 Minutes!” The cumulative effect is both hilarious and horrifying. Marge and the Simpsons children scream in terror at Homer’s insane, static grimace, one that recalls any number of unsettling stares by Kubrick protagonists. [30] As Rachel Elfassy Bitoun observes, “Homer incarnates Jack Torrance and replicates with exactitude Nicholson’s facial mimics, even as a cartoon”. [31]

This parodic manipulation is also rich, intertextually. It should come as no surprise that Kubrick, grand innovator and master of his medium, was himself influenced and inspired by numerous cinematic predecessors – from silent film to experimental and avant-garde works. From early childhood Kubrick was an avid, if not obsessive, filmgoer immersing himself in lowbrow fare screening at dingy New York grindhouses to the highbrow, international and trans-historical programing at MOMA and elsewhere. [32] One of Kubrick’s favourite films from the silent era was Swedish auteur Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Carriage (1921). [33] The scene of a crazed father (played by writer-director Sjöström) using an axe to break through a locked door and enter a room where his wife and children cower is self-consciously reworked in The Shining. However, the disturbingly sardonic and terrifying howl of “Heeeere’s Johnny!” – improvised on set by Nicholson – generates a further layer of horror beyond the kinetic violence of Nicholson’s axe swings and Kubrick’s whip-pan camerawork. [34] In The Simpsons’ Halloween parody Homer’s initial mistake and repeated door assaults also gestures to Nicholson’s action, where he first tears through the apartment’s outer door and smirks mockingly, “Wendy, I’m home”, before proceeding to the bathroom door to repeat the onslaught.

Even at its most marginal or oblique the Kubrick tropes, framing, editing, mise en scène and musical accompaniment showcased in The Simpsons usually engenders the same sense of artistic “defamiliarisation” and satirical impulse as their source of inspiration. [35] In Full Metal Jacket (1987) the overweight and cognitively slow “Private Pyle” (Vincent D’Onofrio) is constantly brutalised in front of his squad while undergoing Marine Corps training at Parris Island. In one scene the troops are shown marching in tight formation to Gunnery Sargeant Hartman’s (R. Lee Ermey) vocal commands, undertaking a switch-shoulder rifle drill. The recruits pass by the mostly static camera in unison in contrast with Private Pyle incongruously waddling a few paces behind them, trousers around his ankles, underpants exposed and sucking his right thumb – an implied punishment from Hartman for some unseen indiscretion. This style of infantalising humiliation finds its way into The Simpsons’ universe when school bully Nelson (“ha-ha”) Muntz gets a comeuppance in “22 Short Films About Springfield” (S7, E21). After mistakenly picking on a giant, Muntz is ordered to march off in front of the Springfield citizenry, mortified, with his pants at his feet. Similarly, in a sequence where Springfield Nuclear Power Plant colleagues (Lenny and Carl) are exercising outdoors, Homer is shown adjacent, hopelessly uncoordinated and with his pants at his heels, pudgy stomach and Y-fronts exposed.

Other Full Metal Jacket tropes appear throughout The Simpsons and former Marine instructor turned actor, R. Lee Ermey, provided a number of guest voice roles in the series. [36] In “Sweet Seymour Skinner’s Baadassss Song” (S5, E19) Principal (here Sargeant) Skinner marches with soldiers but curtly rejects the ‘smut’ of the rhyming song chanted by his squad. Those familiar with the film’s adult content may wonder how The Simpsons will comically adjust the refrain to avoid offense and network censorship. In compliance with Skinner’s demand, the platoon sing:

I don’t know but I’ve been told

The Parthenon is mighty old

Earlier, in “Bart the General” (S1, E5) this Kubrickean trope extends to scenes of Bart marching alongside his classmates, all wearing army helmets, reciting a tamer version of Sargeant Hartman’s ribald marching song from Full Metal Jacket. Instead of “I don’t know but I’ve been told; Eskimo pussy is mighty cold” and “Ho Chi Minh is a son-of-a-bitch; got the blue ball crabs and the seven-year itch”, Bart’s troop sings:

I got a ‘B’ in arithmetic

Would’a got an ‘A’ but I was sick

… In English class I did the best

Because I cheated on the test.

Interspersed between the troops’ refrain are views of Bart supervising his classmates as they run through an obstacle course. The children are shown clambering over monkey bars and other playground equipment at sunset matching the silhouetted soldiers and the obstacle course in Full Metal Jacket.

Elsewhere, Simpsons characters playfully parrot the dehumanising lines or actions from Full Metal Jacket. In “Dead Putting Society” (S2, E6) Bart is forced by Homer to give his golf putter “a girl’s name”, just as Hartman orders his squad to name their rifles after women. [37] Sargeant Hartman’s invective dialogue is parodied in “Sideshow Bob’s Last Gleaming” (S7, E9) when the character of Col. Leslie ‘Hap’ Hapablap, voiced by R. Lee Ermy, lambasts Crusty the Clown’s television sidekick with “What is your major malfunction …”, replacing the movie’s phrase of “numb-nuts” with “… Sideshow Bob”.

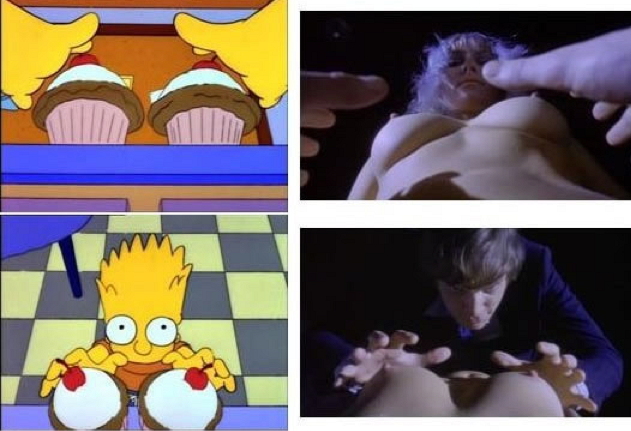

While such vignettes are often interstitial in nature, unrelated or rarely advance narrative or plot, other Kubrickian allusions feature prominently as drivers of action or characterisation. For example, Bart is envisioned throughout The Simpsons as a proto-Alex, sometimes donning a droog outfit or exaggerated false eyelashes. As early as “Treehouse of Horror III” (S4, E5) Bart is shown in Halloween costume dressed as Alex, complete with codpiece, boots, bowler hat, eyelashes and cane/club. Even without the apparel of the film Bart channels a droog-like persona in “A Streetcar Named Marge” (S4, E2) where he lampoons his mother’s affected southern accent as she rehearses for a theatrical role as Blanche DuBois. Bart disparagingly adopts a mock-Cockney voice and describes his head as a “Gulliver”, referencing the Nadsat language used in both the novel and the film version of A Clockwork Orange. More sophisticated is the unwitting subjection of Bart to operant conditioning as part of his younger sister Lisa’s experiment in “Duffless” (S4, E16) to test whether her pet hamster is more intelligent than Bart. Employing behavioural therapy to mildly shock the animal as it approaches food, Lisa discovers the same ploy fails to deter Bart who is shocked repeatedly when reaching for a cupcake. Later, in a scene that pays direct homage in both composition and execution to A Clockwork Orange, Bart sinks to the floor and shudders uncontrollably, replicating Alex’s gag-reaction to the Ludovico technique, a variant on B. F. Skinner’s psychological technique designed to produce an automatic reflexive response, such as when Alex strives to touch the breasts of a topless woman. [38] This satirical vignette manages to bypass the expectations of wholesome family entertainment by alluding to a controversial scene that depicted nudity and abjection, familiar to adults who saw (the originally X-rated) A Clockwork Orange. Given the humorous and experimental logic of the plot in this episode, The Simpsons creators manage to satisfy the curiosity of a general audience while intertextually catering to an adult audience familiar with Kubrick’s film.

In “Much Apu About Something” (S27, E12) Bart informs Homer that, since his dad has stopped strangling him (over his repeated pranks), Bart’s voice has returned to normal and he can sing like an angel. But as Bart imagines returning to his old trickster ways the scene abruptly cuts to a slow-zoom close-up of Bart’s face – a recognisable and iconic Kubrickean technique – matched with the synthesised invocation of Purcell’s score from A Clockwork Orange. Bart stares directly at the viewer and puts on a pair of dark eyelashes while Homer laments: “I never should have bought that Clockwork Orange video for his fifth birthday”. [39] The scene reprises an earlier, more bizarre shot that concludes the “Treehouse of Horror XXI” (S22, E4) where the ‘innocent’, bathing toddler Maggie inexplicably reveals her right eye is similarly adorned with large black lashes. The shot is immediately followed by a reverse-zoom where Maggie pulls out a bowler hat from the bath and replaces her ever-present pacifier with a baby milk bottle. She continues to stare menacingly at the viewer while a variation of “Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary” enhances the Kubrickean association. [40] In terms of the Kubrick/Simpsons epistemology, Maggie’s unexpected ‘twist’ ending/transformation not only references Alex de Large’s iconic appearance but also his problematic bathing in the film (nearly drowned by the police, and later relaxing in the Writer’s bathtub) and the milk/moloko motif, paradoxically, conveying purity and innocence while implying synthetic drug use.

One of the most startling renditions of A Clockwork Orange appears unexpectedly in “Dog of Death” (S3, E19). The Simpsons’ family pet, curiously named Santa’s Little Helper, is abducted by Montgomery Burns in an attempt to improve the stock of his guard dogs. In order to train the normally placid hound into an attack dog, Burns is shown projecting scenes of brutality and violence while Santa’s Little Helper is trussed up in a straitjacket with lid-locks clamping his eyes wide open, wearing an electrical headset similar to Alex while undergoing the Ludovico treatment from Kubrick’s film. As Burns’ assistant Smithers adds liquid drops into the dog’s exposed eyeballs, Burns explains: “Here’s a film that will turn you into a vicious, soulless killer. Enjoy!” With Beethoven’s Ode to Joy playing as the background score a quick montage humorously re-interprets Kubrick’s film-within-a-film to depict: a female poodle struck across its snout with a newspaper; a close up of a human foot deliberately kicking over the contents of a dog’s bowl; a large atomic mushroom cloud; a white cat playing with a ball of yarn; newsreel film of the Hindenburg zeppelin aflame and exploding; a tank crushing a suburban dog kennel; the heavy porcelain lid of a toilet slamming onto the head of a dog as it drinks from the cistern; and archival film of a man (President Eisenhower?) surrounded by others who are amused at his cruelly hoisting up a dog by its ears. The sequence runs less than 20 seconds but brilliantly encapsulates the tenor of Kubrick’s film while paying homage and being entirely consistent within The Simpsons’ cosmology, characterisations and the episode’s narrative arc. [41]

These Simpsons’ vignettes do more than gesture to Kubrick’s works in homage; they embrace the primary importance of concise and time-constricted montage to convey meaning in limited narrative packages. Kubrick has noted his admiration for the formal components of some television advertising as using their audio-visual medium to transcend theatrical paradigms. [42] The best TV commercials, Kubrick opined to The New York Times in 1987, “create a tremendously vivid sense of mood, of a complex presentation of something.” [43] Drawing from Pudovkin as an example, Kubrick recalled a Michelob television advertisement that screened during a NFL Super Bowl telecast:

the editing, the photography, was some of the most brilliant work I’ve ever seen. Forget what they’re doing — selling beer — and it’s visual poetry. Incredible eight-frame cuts. And you realize that in thirty seconds they’ve created an impression of something rather complex. If you could ever tell a story, something with some content, using that kind of visual poetry, you could handle vastly more complex and subtle material. [44]

Despite this observation, Kubrick was also a pioneer of such advertising compositions, evident in the collaborative cut-up style he chose with Pablo Ferro on the Dr. Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange theatrical trailers. [45] At is best, this impressionistic, artistic truncation is displayed by The Simpsons creative team while economically conveying complex themes entwined with family drama. Remarkably, these self-contained sequences are often briefer than a standard 30-second television commercial – whether deployed in postmodern, parodic or intertextual homage.

Nevertheless, anodyne commercial television advertising is a regular target of The Simpsons’ writers (e.g. frequent advertising spokesman Troy McClure). In “Brother, Can You Spare Two Dimes?” (S3, E9) Homer is impressed by a TV infomercial and takes the family to a Springfield furniture outlet to try out a massage chair named Spinemelter 2000. Demanding the attendant turn the machine to “full power”, the increasing vibration sends Homer into a state of psychedelic sublimity. Switching from a close-up of his face to a reverse POV-shot, Homer (and the audience) looks on as his children become stretched and elongated in surreal animation style. Abstract, flashing shards of light expose him to a technicolour, transdimensional experience that replicates Douglas Trumball’s slit-scan ‘Beyond the Infinite’ effects in 2001. In extreme close-up, and to the choral arrangement of Ligeti’s spectral Atmosphères, one eye is shown changing to multiple colours to conclude the sequence, mimicking the ‘star gate’ perspective of astronaut Dave Bowman. Intertextually rich and resonant this Simpsons-2001 homage is playful and humorous while adopting experimental animation across its scant 26 seconds.

Another 2001-inspired Simpsons sequence reworks Kubrick’s inventive application of canonical symphonic scores, frequently juxtaposed incongruously with spectacular montage. In “Deep Space Homer” (S3, E15), after minimal training, the eponymous buffoon is sent by NASA into space in order to boost television ratings. Inside the space shuttle Homer opens a packet of potato crisps that scatter in the micro-gravity. To prevent the chips from clogging the delicate instrumentation, Homer exits his seat and floats in the weightless environment. To the strains of Johann Strauss’s The Blue Danube Homer floats past the potato crisps and chomps away, rhythmically synchronised to the waltz, devouring as he goes. In a remarkable two-shot, audiences are granted the viewpoint of a single ruffled chip smoothly rotating inside the cabin, precisely replicating the docking sequence in 2001 where the Pan Am shuttle aligns its trajectory with the orbiting space station. A cut-away then reveals Homer floating in unison towards this particular chip, rotating his head and opening his mouth to capture the treat. The affection shown in this montage serves both as homage and also amplifies (for the initiated) the fluidity of the animation style in keeping with Kubrick’s original in-camera special effects, themselves almost imperceptible to the public in 1968 as animations. [46]

Similarly, in “Lisa’s Pony” (S3, E8) the opening sequence from 2001 is varied to lampoon Homer’s lack of evolutionary progress, this time displaying the film as ‘letterboxed’ in wide-screen full-frame. More homage than parody, this précised Simpsons rendition even replicates Kubrick’s inter-title typograph. Homer is depicted as one of the proto-humans encountering the mysterious black monolith during the “Dawn of Man” sequence. To the compelling overture of Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra, denoting the invisible intellectual stimuli of extraterrestrials, other man-apes are shown using a bone-tool, harnessing fire and inventing the wheel. However, proto-Homer simply pushes the monolithic slab slightly sideways to create a lean-to upon which he rests and quickly dozes. A fast dissolve comically shows Homer in the exact same position, asleep on the job in his office chair at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant. No jump-cut here to convey the advance of weapon-tools across millions of years, just a rapid overlap to satirically confirm homo Homer’s developmental stasis.

However, the zenith of Kubrickean references in The Simpsons was attained in the 2014 sub-episode “A Clockwork Yellow” featured in “A Treehouse of Horror XXV” (S26, E4) that runs just over eight minutes. Here again homage blends with parody, however, in this instance virtually the entire Kubrick oeuvre, as well as the filmmaker’s public persona, are the targets of satire. For example, in an inventive and richly detailed single shot, four Kubrick films are lampooned simultaneously, while artfully replicating the Clockwork Orange discotheque scene where Alex seduces two teenage girls. Droog-like “glug” Dum (Homer) meets Marge in front of a large 33rpm vinyl LP display, featuring various records: “Dr. Strangelaugh” with a black and white cover featuring the laughing Dr. Hibbert; “Paths of Gravy” showing Homer in a WWI military uniform guzzling a dark sauce; “Full Milhouse Jacket” depicting Bart’s bespectacled friend in combat fatigues holding a rifle (resembling Private Joker); and “Do’h!-Lita” with Homer wearing nymphetish, heart-shaped sunglasses and sucking a lollipop, that recalls the Kubrick film’s promotional poster. The intertextual layers again approach meta-homage since this single composition references Kubrick’s own act of self-parody. [47] During this scene filmed in London’s Chelsea Drug Store, Alex passes corridor shelving that displays the official MGM soundtrack to 2001 (with accompanying artwork by Robert McCall), and he then stops before an array of LPs with an unofficial ‘knock-off’ version of the 2001 soundtrack prominent in the lower centre of the frame.

Hence, “A Clockwork Yellow” demonstrates that The Simpsons does not simply ape Kubrick’s works, rather the series skillfully reinterprets and frequently revisions the auteur’s now canonical mise en scène, montage and non-diegetic sound. The opening frames of “A Clockwork Yellow” reveal Simpsons barkeeper Moe Szyslak in tight close-up, dressed like a droog (a “glug” named “Moog”), a cartoon simulacra of Anthony Burgess and Stanley Kubrick’s Alex de Large (Malcolm McDowell), while a variation on Wendy (Walter) Carlos’ synthesized dirge underscores a slow track backwards. [48] Moog’s first-person narration adroitly modifies the futuristic argot of the book and film and situates him inside a setting similar to the Korova milkbar:

That was me, when I was a young hoodlink, with me three bestest glugs, Leonard, Carlton and Dum. We was narsty tastards, we were, even though we dressed like Carol Channing’s backup dancers. Some days, we’d employ a bit of the bash while having a go at the West End Wiseguys.

With his fellow glugs (replicating Georgie, Pete and Dim), Moog’s posture is framed in the same composition as Kubrick’s droogs, just as is the milkbar’s white typography (‘nonfat moloko’) and production design cleverly replaces Kubrick’s naked female mannequins (by Liz Moore based on works by Alan Jones) with statues of Duff beer mascots (Dizzy, Queasy, Sleazy and Tipsy).

The creative tension between authentically rendering A Clockwork Orange’s adult-oriented imagery and plot is wonderfully negotiated in two ingenious scenes that bypass the network censors. Firstly, after some comically stylised ultra-violence with a rival gang, Moog and his glugs approach a hesitant, mini-skirted blonde woman outside a UK Kwik E-Mart, to “cap off the night with a little of the old ‘in-out’”. After a breathless pause … the scene literally jump-cuts to inside the shop as the glugs repeatedly leap through the retractable glass doors, calling out in concert “In”, then jumping backwards with “Out”. An equally audacious adult allusion appears ‘Years later’ when Moog is subjected to an assault in his home (reprising Alex’s gang) by a group of teen thugs familiar in The Simpsons as school bullies dressed as droogs (Kearney, Nelson, Dolph and Jimbo). Conflating several elements of Alex’s attack at The Writer’s “home” and the separate murder of the Cat Lady in A Clockwork Orange, Moog is brutalised by the youths. During the assault Kearney spies a genital-shaped sculpture – a bust of cartoonist Al Capp’s “Shmoo” – and the droog proceeds to slam the phallic figurine down onto Moog’s head. [49] Apart from the brazenness of this Kubrick homage, the short Simpsons montage recreates a sophisticated assemblage of styles, from Kubrick’s favourite angled view upwards from the floor, to the rapid inward and outward zooming, and the final pop comic panel frame that acknowledges the Cat Lady’s “filthy” artworks.

“A Clockwork Yellow” contains a range of complex and nuanced Kubrick “quotations”, some as parody and others as homage. After Dum picks up Marge in a scene replicating the movie’s naked, threesome tryst, to the same accompaniment of Rossini’s William Tell Overture and high-speed montage, Dum proceeds to spend time doing virtually anything but have intercourse. Marge lays on the bed, at first expectantly and then bored (to the point of reading Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange), while Dum eats a variety of foods, drinks beverages, cooks, chews gum, changes the bedding, plays bongos, exercises and finally kisses Marge.

The temporal dimension of The Simpsons’ parodic montage is also foregrounded when Moog convinces Dum (since retired from the biffo) and Leonard and Carlton (now thuggish cops) to regroup for a final bit of ‘noggin boggin’. In slow motion the quartet are shown strolling along a canal surrounded by brutalist architecture as Moog narrates, over a medley of Rossini tracks: “Once again the Glugs was hittin’ the streets all slow-motion like. And just as scarifying and intimidato as ever”. Dum is shown lagging behind, comically out of synch with the self-consciously, artificial slo-mo montage.

Perhaps the canniest of the self-referential “A Clockwork Yellow” homages occurs inside Montgomery Burns’ vast mansion where a masked orgy is underway, revealed as the glugs enter for a bit of the old “home invasion”. A swift series of cuts allude to Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut (1999), by depicting an array of Simpsons characters (still identifiable) under their carnivalesque masks. The breasts of numerous topless women are deliberately obscured by anonymous characters, named “sex view blockers”, who diligently place inanimate objects in front of the hostesses (e.g. wine glasses, books, trays and plants). [50] This overt and conspicuous censorship, referred to expositionally by Burns, cleverly evokes the controversy of Warner Brothers adding digital figures to Eyes Wide Shut after Kubrick’s death in order to secure an American R-rating to bolster box-office. [51] During the group melee that ensues, choreographed to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, various Kubrickean texts are parodied including 2001 (Dum using a large bone to assault Sideshow Mel, and an iPhone appearing as a monolith); A Clockwork Orange (Moog’s “I was happy” narrated finale); Full Metal Jacket (Private Pyle interrupted in the lavatory with his rifle); and Barry Lyndon (1975) via the hilariously self-conscious comment from Simpsons pop culture pedant, Comic Book Guy, sans mask and dressed as an eighteenth century nobleman. Comic Book Guy duels with glug Leonard but after firing his pistol the leaden shot falls short and bounces off Leonard’s codpiece, severing the left leg of Comic Book Guy at the knee. Hopping gingerly on the remaining leg, he ironically admits: “even I forget what this is a reference to!” With great intertextual aplomb, this gag-line acknowledges the viewers who will recognise the deliberate nod to actor Ryan O’Neil as Barry in Kubrick’s lesser known and comparatively little seen mid-1970s film.

As Simpsons’ critic Matthew A. Henry points out in The Simpsons, Satire, and American Culture, the genius of this television series is it capacity to simultaneously engage with contemporary socio-political satire while invoking a myriad of cultural references within the restrictive genres of network family sitcom and mainstream animation. [52] Amidst the program’s canny evocations of history and zeitgeist a recurring cultural barometer has been the cinema of Stanley Kubrick. But The Simpsons’ admiration for the auteur was mutual. Kubrick’s daughter Katharina has confirmed that her father was “quite a fan” of the show and chuffed at the references to his movies. His long-time personal assistant Anthony Frewin also recalled: “[Stanley] thought The Simpsons was wonderfully funny and inventive how it satirised so many aspects of the American dream.” [53] Now approaching its 28th season, the influence of the Kubrick canon on The Simpsons displays little sign of diminishing, or the oeuvre (and Kubrick’s public persona) losing relevance into the twenty-first century.

NOTES

[1] Anon. “Matt Groening’s 100 Favorite Things”,

[https://www.ilxor.com/ILX/ThreadSelectedControllerServlet?boardid=40&threadid=27279]

[2] John T. Roosevelt, “There are Way More Stanley Kubrick References in The Simpsons Than You Ever Knew”, 6 June 2016,

[http://www.rsvlts.com/2016/06/06/there-are-way-more-stanley-kubrick-references-in-the-simpsons-than-you-ever-knew/]

[3] David Mirkin, The Simpsons: The Complete Sixth Season, 2005. DVD commentary for “Treehouse of Horror V”. In contrast, Matt Groening revealed in his accompanying DVD commentary that he hadn’t watched The Shining up to that point.

[4] James Marinaccio’s skillfully edited and virtually complete video compilation of Kubrick references in The Simpsons can be viewed at: [https://vimeo.com/221161125]

[5] For example, missing from this discussion is the delightful parody of hal 9000 by Pierce Brosnan as the amorous Ultrahouse 3000 in “Treehouse of Horror XII”, and multiple quotations from Dr. Strangelove. On the latter, see Mick Broderick, Reconstructing Strangelove: Inside Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Nightmare Comedy’. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), p. 195.

[6] Stanley Kubrick Archive file SK/11/1/21, University of the Arts London.

[7] Stanley Kubrick Archive file SK/11/1/21, University of the Arts London.

[8] Stanley Kubrick Archive file SK/11/1/21, University of the Arts London.

[9] Stanley Kubrick, as quoted by John Hofsess, in Gene D. Phillips (ed.), Stanley Kubrick Interviews. (Jackson Miss: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), p. 107.

[10] See [http://twistedsifter.com/2011/12/stanley-kubricks-new-york-photos-1940s/]

[11] Robert Stam, Keywords in Subversive Film/Media Aesthetics. (Chichester UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015), p. 86.

[12] Robert Stam, Keywords in Subversive Film/Media Aesthetics. (Chichester UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015), p. 87.

[13] Michael V. Tueth, “Back to the Drawing Board: the Family in Animated Television Comedy”, in Carol A. Stabile and Mark Harrision (eds). Prime Time Animation: Television Animation and American Culture. (New York: Rouledge 2003).

[14] Matthew A. Henry, The Simpsons, Satire, and American Culture (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 37.

[15] Todd Leopold, “Matt Groening looks to the future”, CNN, 26 February 2009, [http://edition.cnn.com/2009/SHOWBIZ/TV/02/26/matt.groening.futurama/index.html]

[16] Deborah Groening quoted in John Ortved, Simpsons Confidential: The Uncensored, Totally Unauthorised Account of the World’s Greatest Television Show and the People Who Made It. (London: Ebury Press, 2009), p. 269.

[17] John Ortved, Simpsons Confidential: The Uncensored, Totally Unauthorised Account of the World’s Greatest Television Show and the People Who Made It. (London: Ebury Press 2009), p. 268.

[18] John Ortved, Simpsons Confidential: The Uncensored, Totally Unauthorised Account of the World’s Greatest Television Show and the People Who Made It. (London: Ebury Press 2009), p. 171.

[19] In an earlier episode “Brother from the Same Planet” (S4, E14) Bart is left abandoned in the rain and uses telepathy to command Homer to ‘pick up Bart’. However, it is Bart’s school friend Milhouse who receives the communication, writing the message backwards on a wall and then twiddling his index finger, like Danny channeling “Tony” in The Shining. The correctly aligned text is then revealed in a reverse shot of a mirror.

[20] Mick Broderick, Reconstructing Strangelove: Inside Stanley Kubrick’s “Nightmare Comedy”, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), pp. 97-114.

[21] According to IMDB.com: “The original title was The Incredibly Strange Creature: Or Why I Stopped Living and Became a Mixed-up Zombie. Columbia Pictures threatened to sue writer/director/star Ray Dennis Steckler, accusing the title of being too similar to their upcoming Stanley Kubrick film […] Steckler, amazed that Columbia would feel so threatened by a $38,000 film, phoned the studio to straighten things out. He made no progress until he demanded that Kubrick get on the line. When Kubrick picked up, Steckler suggested the new title, Kubrick accepted, and the matter was dropped”, IMDB.com Trivia [http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0057181/trivia]

[22] Jan Swafford “Ligeti: A Sound Odyssey”, slate.com, [http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/music_box/2008/07/ligeti_a_sound_odyssey.html]

[23] More recently King was sued by the owners of comic book The Rook over the rights to a character used in the film adaptation of his The Dark Tower (Nikolaj Arcel, 2017). See Casey Davidson, ‘Stephen King wins lawsuit’, Entertainment Weekly, 22 April 1994, [http://ew.com/article/1994/04/22/stephen-king-wins-lawsuit/], and “Stephen King sued over ‘The Dark Tower’ character”, Toronto Sun, 29 March 2017, [http://www.torontosun.com/2017/03/29/stephen-king-sued-over-the-dark-tower-character]

[24] The elevator scene in both The Shining and The Simpsons parody-homage strongly recalls the oozing blood-red mass that pours out of the twin cinema doors in The Blob (Irvin Yeaworth and Russell S. Doughton Jr., 1958).

[25] As Linda Hutcheon has asserted, parody “paradoxically brings about a direct confrontation with the problem of the relation with the aesthetic to a world of significance external to itself, to a discursive world of socially defined meaning systems (past and present) … to the political and the historical”. This interpretation aligns well with the stated agenda of Groening and the TV series.

[26] Umberto Eco, The Limits of Interpretation. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 89.

[27] Umberto Eco, The Limits of Interpretation. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 88.

[28] Tasha Robinson, “Brad Bird interview”, The A.V. Club, 3 November 2004, [http://www.avclub.com/article/brad-bird-13899]

[29] The famously chilling line from The Shining (“all work and no play…”) has assumed the status of a regular meme in The Simpsons’ cosmology. Variations appear in the regular opening title sequences where Bart writes lines after class on a blackboard (S4, E9), and in one instance, turns to see a cartoon version of Stephen King (S25, E2) writing the same line, although Homer-like, it is manically spread across the entire classroom.

[30] On Kubrick and his characters’ looks and stares, see Michel Ciment, Kubrick: The Definitive Edition. (London: Faber & Faber 2003) and Alexander Walker, Sybil Taylor and Ulrich Ruchti, Stanley Kubrick, Director: A Visual Analysis. (London: Norton, 1999).

[31] Rachel Elfassy Bitoun, “The Simpsons and Hollywood: Revisiting Our Favourite Classics”, 20 January 2014, [https://the-artifice.com/the-simpsons-and-hollywood/]

[32] Vincent Lobruto, Stanley Kubrick: a Biography. (New York, D.I. Fine Books, 1997).

[33] There are several lists of films that Kubrick admired. According to his brother-in-law and long-time Executive Producer, Jan Harlan, The Phantom Carriage was a Kubrick favourite. See Nick Wrigley, “Stanley Kubrick, cinephile”, British Film Institute online, 25 October 2013,

[http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/polls-surveys/stanley-kubrick-cinephile]

[34] On the improvisation, see Christopher Hooton, “Watch Jack Nicholson prepare to film The Shining’s axe scene”, The Independent, 3 August 2016, [http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/news/watch-jack-nicholson-prepare-to-film-the-shining-s-axe-scene-a7169566.html]. Video of Kubrick filming this shot can be viewed here: “The Shining – Rare behind-the-scenes footage” [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1w8Ykhk7FwU]

[35] On Kubrick’s defamiliarisation, see: Greg Jenkins, Stanley Kubrick and the Art of Adaptation: Three Novels, Three Films. (Jefferson NC: McFarland & Co, 1997); Stuart Y. McDougal, “What’s It Going to be then, eh?”, in Stuart Y. McDougal (Ed.), Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003); and Maria Pramaggiore, Making Time in Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon: Art, History, and Empire. (New York: Bloombury, 2015).

[36] On cinematic tropes, see James Monaco, How to Read a Film – The World of Movies, Media, and Multimedia : Language, History, Theory. 3rd edition, (New York: Oxford university Press, 2000).

[37] After two unsatisfactory attempts, Homer forces Bart to call his putter “Charlene”, the same name adopted by Private Pyle in Full Metal Jacket.

[38] The cupcake sequences can be viewed here: [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D0uUF3mK7Xk]

[39] Bart’s ‘Alex de Large’ scene can be viewed here: [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xtEPMGi_ogA]

[40] Maggie’s bathing shot can be viewed here: [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KGM_-ToDIng]

[41] Throughout the series the producers and writers continually raised issues concerning the rights of animals and their often barbarous or neglectful treatment. Like Kubrick himself, a devoted animal lover (sometimes to the point of distraction), Simpsons’ co-creator and Executive Producer, Sam Simon, was a renowned animal rights advocate who left a considerable portion of his $100 million-plus estate to charities such as PETA. On the extraordinary lengths Kubrick went to in helping sick or injured animals, see: Emilio D’Alessandro and Filippo Ulivieri, Stanley Kubrick and Me: Thirty Years at His Side. (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2016). For Sam Simon, see: “Sam Simon Estate Announces the Formation of The Sam Simon Charitable Giving Foundation”, 30 May 2017, [http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/sam-simon-estate-announces-the-formation-of-the-sam-simon-charitable-giving-foundation-300465672.html].

[42] “Economy of [structural] statement is not something films are noted for”, Kubrick remarked to Francis Clines, ‘Stanley Kubrick’s Vietnam War’, New York Times, 21 June 1987, reprinted in Gene D. Phillips (ed.), Stanley Kubrick Interview., (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), p. 171.

[43] Francis Clines, “Stanley Kubrick’s Vietnam War”, New York Times, 21 June 1987, reprinted in Gene D. Phillips (ed.), Stanley Kubrick Interviews. (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), p. 175.

[44] Kubrick interviewed by Tim Cahill, Rolling Stone, 1987, [http://www.rollingstone.com/culture/news/the-rolling-stone-interview-stanley-kubrick-in-1987-20110307]. Kubrick does concede, however, that this truncated form is: “a bit impractical […] I suppose there’s really nothing that would substitute for the great dramatic moment, fully played out.”

[45] See: Lola Landekic, “Pablo Ferro: A Career Retrospective”, Art of the Title, 8 April 2014,

[http://www.artofthetitle.com/feature/pablo-ferro-a-career-retrospective-part-1/]

[46] On animation effects in 2001, see: “Douglas Trumbull: Master class”, Toronto International Film Festival, [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBaZQojd1_s]

[47] For an expert analysis of the sequence see John Coulthart, “Alex in the Chelsea Drug Store”, 13 April 2006, [http://www.johncoulthart.com/feuilleton/2006/04/13/alex-in-the-chelsea-drug-store/].

[48] The set up identically mirrors the opening of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, which itself gestures to the opening close-up of Edie Sedgwick in Andy Warhol’s 1965 black and white adaptation Vinyl. Moe’s character “Moog” also refers to the electronic synthesizer used by Walter Carlos for the movie soundtrack.

[49] Kubrick’s sculpture was one of Dutch artist Herman Makkink’s works titled, “The Rocking Machine”.

[50] One “bare naked lady” is shown holding a copy of a Taschen book titled Naked London featuring a nude, reclining Winston Churchill on the cover. The gag refers to the transatlantic art publisher of expensive first-edition, post-Kubrick volumes, authorised by the Kubrick estate. For examples, see: [https://www.taschen.com/pages/en/company/blog/281.stanley_kubricks_napoleon.htm] and [https://www.taschen.com/pages/en/company/blog/34.the_making_of_2oo1_a_space_odyssey.htm]

[51] For comparison between the digitally censored and uncensored prints, see: [http://www.movie-censorship.com/report.php?ID=853344]

[52] Matthew A. Henry, The Simpsons, Satire, and American Culture. (New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2012).

[53] Author Skype interview with Katharina Kubrick, May 2016, and email from Anthony Frewin, June 2017.