Parallel to the exponential growth in academic interest in Stanley Kubrick, brought about by the opening of his archive at the University of Arts London (UAL) in 2007, there has been an increase in Kubrick themed exhibitions, academic, artistic or otherwise. Behind both trends is the idea of uncovering so-called new perspectives about Kubrick and his films. What follows is an exploration of the curatorial practices of these Kubrick related exhibitions and the way they interpret Kubrick’s life and work in the context of the new perspectives they claim to reveal. Focus is given to two recent exhibitions: the first a small-scale academic exhibition, Stanley Kubrick: Cult Auteur (2016), held at De Montfort University (DMU) in Leicester; [1] the second is the artist based Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick (2016), held at Somerset House in London. The article contrasts the curatorial practices in the construct of narratives about Kubrick by engaging with these exhibitions and the motivations behind their curation, the fandom of their curators seemingly a driving force.

But I want to first turn my attention to San Francisco, where on 1st May 2016 the Contemporary Jewish Museum (CJM) issued a press release announcing that it would be the fifteenth host of the official Stanley Kubrick travelling exhibition. The statement was sub-headlined, ‘previously inaccessible materials from Kubrick’s private estate provide an in-depth view of the legendary filmmaker’s life and work’. [2] The Stanley Kubrick travelling exhibition presented at the CJM had originally debuted at the Deutsches Filmmuseum in Frankfurt in 2004, following permission from the Kubrick Estate for the museum to “explore the extensive archives Kubrick had maintained at his home and workplace in London”. [3] Tim Heptner, of Deutsches Filmmuseum, curated the exhibition from Kubrick’s archive at UAL. The exhibition he realised was heavily focused on presenting a biographical overview of Kubrick and his films, coordinated with the supervision of the Kubrick Estate – in particular Jan Harlan and Christiane Kubrick – presenting close to 1000 objects, including props, scripts and correspondence, alongside biographical text.

Some reviews of the exhibition at its various calling points around the globe (the exhibition is always uniquely different in some way at each stop) have commented on how the exhibition reveals little about Kubrick that is not already known and is instead reverential. Lucian Robinson of the Financial Times said of the exhibition’s Paris showing in 2011 that:

Partly because the show has been created by Kubrick’s widow, Christiane, and brother-in-law, it is reverential in tone, but you never quite lose the suspicion that almost every sentence written about Kubrick could be followed by an equally true, contradictory parenthesis. [4]

The most scathing review of the exhibition came from the co-screenwriter of Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Frederic Raphael. Perhaps still bruised from the fallout of the publication of his memoir, Eyes Wide Open (1999), Raphael criticises the way the exhibition venerates Kubrick, elevating him to the status of “transcendent genius”, [5] with the biographical text and supporting catalogue depicting Kubrick as a man “without humour and without faults”. [6] What was being presented was in effect a sanctioned biography of Kubrick, rather than any real critical interpretation or understanding. Whatever Raphael’s ulterior motives were in being so strident in his criticism of the Stanley Kubrick exhibition, he does raise interesting points in the ways in which the exhibition presents the director and his work as “museum pieces”, [7] the props and other paraphernalia displayed as relics. Raphael views the exhibition as a shrine to the mass of objects Kubrick collected throughout his life.

The exhibition up to 2011 was presented chronologically before being given a more thematic emphasis for its debut in Los Angeles in 2012. The intent of this new thematic approach was, according to exhibition designer Patti Podesta, to fragment things “in order to create these very intensified moments”, [8] and forcing the spectator to re-experience Kubrick and the way they perceived his work. Such fragmentation has been a continuing theme of many Kubrick books and non-official exhibitions, with a new phrase becoming common parlance in Kubrick scholarly circles – new perspectives. This phrasing saw a turn in Kubrick studies to the methodological toolkit of the New Film History, led by Peter Krämer amongst others. An edited volume, Stanley Kubrick: New Perspectives (Ljujic, Krämer and Daniels, 2015), culminated from this growing scholarly movement, centred on the use of the Stanley Kubrick Archives at UAL. The introduction to the volume suggests that the new perspectives being sought in Kubrick Studies was a key aim of the Stanley Kubrick Archive, following its donation to UAL. The intention of its use was as follows:

[It was donated] with the understanding that students, scholars and indeed members of the public would be able to use it to learn about the making, marketing and reception of his films, and that young artists would be able to take inspiration from the archive to create new works. [9]

It is the latter two groups mentioned above – the public and artists – that are of particular interest: how is Kubrick presented through exhibitions to the public and how do artists make use of his work in new interpretations? Curatorial practice of Kubrick outside of the official Stanley Kubrick exhibition has burgeoned, with several exhibitions having taken place around the world that often, but not exclusively, make use of archival material to contribute toward the unveiling of new perspectives, a concern not just of scholars, but also the wider Kubrick fan base.

The two exhibitions that are the primary concern of this article aim to offer their audience such new perspectives on Kubrick’s life and work, but the curatorial practices of each differs somewhat. Stanley Kubrick: Cult Auteur offers a more traditional exhibition experience, one rooted in the historicising of Kubrick and, to borrow Raphael’s phrase, turns objects from Kubrick’s archive into museum pieces. [10] In contrast, Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick is a much more interactive exhibition experience, contemporising Kubrick with curatorial practices that turn his work into new and original artistic statements. Both however – and perhaps more importantly – deify Kubrick and his films, motivated in large by the fandom of their curators. By analysing the narrative constructs of the life, work and personality of Kubrick in exhibition case studies, we can begin to understand further the supposed new perspectives of these exhibitions. I, however, first want to look more closely at the issue of exhibition curation.

The Role of the Curator

The curator’s role can be simplified to one of author. After all, despite whatever exhibition practices curators employ, they are still aiming to provide a narrative (thematic, chronological, historical) experience for the audience. Terry Smith defines curation as the bringing together of either new or existing objects and works “into a shared space … with the aim of demonstrating, primarily through the experiential accumulation of visual connections, a particular constellation of meaning that cannot be made known by any other means”. [11] Smith’s is a traditional outlining of the role, one that does not consider fully the word curate itself and its proliferation across a variety of mediums and usages. Consideration of this is given by Hans Ulrich Obrist in his Ways of Curating (2014): to curate is not just to stage an exhibition of art work, but is a term applicable to a multitude of contexts (curating a wine shop, a website, etc). [12] What this exponential contextual usage of the word curate demonstrates is the “increase in the amount of data created by human societies” [13] ; we live in an era of knowledge overload and in order to create meaning out of this abundance of knowledge, individuals select – or curate – narratives that lead to a shared understanding.

Knowledge overload is prescient in film history, with the New Film History’s key methodological tool being the preservation and use of the archives of studios, directors, actors, producers and even cinema theatre chains. The Stanley Kubrick Archive alone contains a staggering 800 linear metres of shelving and is the largest publicly available archive of any filmmaker. [14] For the ideologues of the New Film History, archives are a vital scholarly tool to the interpretation of film and filmmakers. But for the wider public, such archival material is not usually consumed through academic texts, but their curatorial interpretation. There is a vacuum within film studies in understanding how exhibitions influence the way an artist or filmmaker and their work is received, interpreted and contextualised by the wider critical and public sphere, beyond the academy. [15] Surrounding exhibitions, there is often a programme of events, from film screenings to public talks, which further the narrative that the public consumes. This is a concern in Kubrick studies, where one of the primary intents of the Stanley Kubrick Archive was for the exhibition of objects to the public and to inspire artistic works. One only has to look to the official Stanley Kubrick travelling exhibition to see the amount of visitors such exhibitions can attract; its residency at the LACMA in Los Angeles drew approximately 250,000 visitors between November 2012 and June 2013, [16] whilst at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Monterrey, Mexico it attracted nearly 100,000 visitors between March and July 2015. [17] Therefore, there needs to be a turn in Kubrick studies to both the scholarly understanding of the proliferation of Kubrick exhibitions and of the curatorial practice in the narrative construct of Kubrick and his work.

There are variables in play that complicate the curatorial role and the communication of knowledge in the need to arrange and organise objects in the exhibition space. The curator alone can never wholly anticipate the experience of the exhibition visitor; curators have expressed their constant re-evaluation of the complex relationship between the exhibition space, the objects on display and the visitors. The exhibition is the space where a dialogue takes place between the curator and the spectator. Whatever experience is undertaken during that spectator’s journey through the exhibition, it is primarily one of the “development of critical meaning in partnership and discussion with artists and publics”. [18] This critical meaning stems not just from the selection of objects, but also how they are displayed, the space they are displayed in, the interpretative and factual text surrounding the objects and the creation of any other promotional material, such as leaflets or catalogues. [19] Viewing the role of the curator in this context positions them as “a kind of interface between artist, institution, and audience” [20] in the interpretation of meaning and narrative. The aim, ultimately, is to influence a spectator of the curator’s point of view:

The exhibition works above all to shape its spectator’s experience and take its visitor through a journey of understanding that unfolds as a guided yet open-weave pattern of affective insights, each triggered by looking, that accumulates until the viewer has understood the curator’s insight and, hopefully, arrived at insights previously unthought by both. [21]

The narrative development of an exhibition has become an area of burgeoning scholarly inquiry in art history and curatorial studies, a prime research topic being the documenting of the behind-the-scenes curation of exhibitions to uncover the assumptions and contingences that underpin curatorial practice. The following case studies of Kubrick exhibitions will endeavour toward this goal and examine the curatorial thought behind the construction of new perspective narratives.

Historicising Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick: Cult Auteur, held at De Montfort University (DMU) in Leicester from 10th May to 3rd June 2016, was an exhibition co-curated by Ian Hunter and myself, both of the Cinema and Television History Research Centre, and Elizabeth Wheelband of DMU’s Heritage Centre. I say co-curator as the curatorial duties were shared, with various individuals taking on the mantle of lead curator in the planning and eventual realisation of the exhibition. The sharing of curatorial roles in the devising of exhibitions is not altogether uncommon, being a documented practice at museums such as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where a case study of the exhibition 010101 (2001) revealed staff referred to their respective roles as being blurred, with research trips and knowledge being shared and with the curatorial hierarchy being disrupted. [22]

The motivation for Stanley Kubrick: Cult Auteur came about as part of a three-day academic conference, Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective, convened by Ian Hunter at DMU in May 2016. The exhibition was launched during the conference with an introduction by Jan Harlan. Objects for the exhibition were curated from the Stanley Kubrick Archive at UAL and permission was required from the Kubrick Estate and Archive donors, which was swiftly obtained following the backing of Harlan in 2015. However, there was no interference in the way these objects should be presented or in the theme of the exhibition by the Kubrick estate. There were, however, suggestions from the staff at UAL about potential archive objects that would complement the exhibition’s theme, including the infamous scrapbook from The Shining (1980).

The theme of the exhibition – the cult films and the auteur status of Kubrick – was set by Ian Hunter, stemming from his own research interests in cult cinema. [23] Over the following weeks, time was spent in the Kubrick Archive at UAL to devise a narrative around the objects selected, focusing on four key films: 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), The Shining and Eyes Wide Shut. Contingency played a large factor in the selection of objects given the extent of the Stanley Kubrick Archive and the oft-unreliable nature of archival cataloguing. An entry in the online UAL archive may record only one or two key elements of any given archive box, the contents of which are often far greater than one would assume from reading the entry. Thereby, a range of boxes, whose titles piqued my interest, were selected and entire contents gone through, building up a large list of potential objects that were suitable to the exhibition and its theme. And it was the theme of fandom that gradually became the central narrative to the exhibition, used in publicity material and the exhibition program:

Stanley Kubrick was a legendary director, whose thirteen films have become iconic within popular culture. The four films represented in this pop up exhibition are masterpieces of cult cinema, which are continually consumed and (re)interpreted by his fans. [24]

Hunter defines cult film as being a cultural object with a “devoted following or subcultural community of admirers” [25] ; the latter, in short, are fans who, as set out in the exhibition publicity, consume and reinterpret the films, key activities in cult film fandom. [26] And such activities extend to film academia “to unveil what the film is really about or doing, even and especially when ordinary audiences don’t notice it”. [27] Eyes Wide Shut exemplifies such deep textual analysis in search of symbolic meaning, a film with a cult basis that stems from the conspiratorial readings of its central orgy sequence and the belief that Kubrick was crafting a coded narrative about the Illuminati. [28] To play into this theme, several props were selected for the exhibition that contained these supposed secret codes, including the napkin Nick Nightingale (Todd Field) gives to Bill Harford (Tom Cruise) with the password ‘Fidelio’ written on it; the warning letter given to Harford at the gates of the mansion; and a mask and a cloak from the orgy sequence.

However, the aim of the Eyes Wide Shut section was to primarily offer yet another reinterpretation, away from such conspiratorial readings, by presenting materials that would most likely not have been seen before, particularly artwork by the cover artist Chris ‘Fangorn’ Baker. [29] Baker’s images depicted Alice’s (Nicole Kidman) nightmare, in which she finds herself having sex with the naval officer amidst an orgy of strangers. These images were presented alongside a draft copy of Raphael and Kubrick’s script, opened to the pages of Alice’s nightmare. [30] Given the lacklustre response to Eyes Wide Shut, the exhibition narrative is fashioned around inaccessible objects and rarely seen items to re-experience the film as being “an intimate examination of marriage, love and sexual fantasy … an odyssey of the subconscious, as Bill uncovers the darkest recesses of human desire”. [31] The curation of Stanley Kubrick: Cult Auteur played into a trend for the need in Kubrick fandom to acquire a closer experiential understanding of Kubrick and his films. It is part of the fetishising of Kubrick, with the exhibition being part of a series of exhibitions that offer new perspectives via a tangible physical look at objects that Kubrick possessed and worked with and to use these to re-consume and re-interpret his work. Other similar exhibitions, like Stanley Kubrick: New Perspectives (2014), have utilised archival material from UAL for this purpose. New Perspectives, curated by Marianne Templeton and held at London’s Work Gallery, sought new perspectives by examining the iconic spaces and environments from three Kubrick films: the Discovery space ship from 2001: A Space Odyssey, the Overlook Hotel from The Shining and Hue City from Full Metal Jacket (1987). Once more, accessibility is at the heart of New Perspectives, with its publicity stating:

Through original documents and photographs … the exhibition provides a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the extensive research, innovative techniques and meticulous designs Kubrick used to seize the imaginations of audiences for generations. [32]

The auteur status of Kubrick is central to this narrative construct in New Perspectives, just as it is in Stanley Kubrick: Cult Auteur; his “fastidious attention to detail” and of his being a “voracious absorber and synthesizer of information”, [33] play into the construct of the Kubrick myth and of his legendary control. [34] Kubrick, after all, can be seen to inhabit a sub-cultural space between art cinema and cult cinema, “underpinned by aspects of film culture heavily associated with both art and cult cinema: such as, crucially, cult auteurism”. [35] The reverence of the official Stanley Kubrick travelling exhibition is also detected in these non-official exhibitions. In Cult Auteur, the archival objects are displayed in glass cubes as rarefied artefacts; in New Perspectives, the exhibition is laid out in a minimalist style, with set photographs and letters treated as works of art, framed on the wall against matte black backgrounds. Similarly, Stanley Kubrick, Photographer (2012), held at The Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, exhibited photographs taken by Kubrick during his time at Look magazine. The exhibition, ostensibly presenting itself as an historical art exhibition, also placed five televisions around the gallery space, playing clips from Killer’s Kiss (1955) and inviting comparisons of Kubrick’s photographic images and his early film work. Publicity for the exhibition commented on this curatorial motivation:

The sequential construction of his photojournalism … already reflects a cinematographic viewpoint. His lens captures a portrait of America right after World War II – a central theme in Kubrick’s films. This idea of social portrayal is at the heart of our presentation of Kubrick and informed our organization of his documentary photographs. [36]

The fetishising of Kubrick informs this narrative construct, building origin myths around him, with authoritative suggestions of “from whence thy genius sprung”. [37] Reviews of the exhibition drew on this idea, talking about Kubrick in the 1940s and early 1950s and this being a period that his aesthetics were established. Rather than look at the photographs on their own terms, they inevitably draw comparison to his later film work and are retrospectively examined for signs of a Kubrickian aesthetic. Just as a branch of Kubrick studies and fandom is concerned with psycho-historical readings of Kubrick, [38] these exhibitions, which historicise the director, search for a coded aesthetic and interpretive reading that is detectable from the beginning of his career. Links are invariably built into the new perspective narratives between each of the films and key moments in Kubrick’s life, such as working at Look. Seemingly incidental objects displayed in Cult Auteur – a napkin, a poorly realised sketch, typewritten notes – are turned into rarefied, even fetishised, relics enshrined in glass casing and surrounded by commanding biographical text that asserts they are “key to the understanding of Kubrick as a visionary auteur”. [39] They are the codes to unlocking Kubrick’s secret messages, his film puzzles to be solved. Just as Kubrick fandom encourages the re-consumption and reinterpretation of his films, and of the fetishising of the man, historicised exhibitions such as Cult Auteur promote further reinterpretation and fetishising of the myth of Kubrick through the consumption and investing of authority in his personal archive.

Contemporising Kubrick

If Stanley Kubrick: Cult Auteur was both a curatorial reinterpretation of Kubrick’s myth as well as an historicising of his work, James Lavelle and James Putnam’s co-curated Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick is a contemporary reworking of the Kubrick myth to create a new experiential understanding of his films. Lavelle started out as a DJ, before co-founding the electronic music record label Mo’Wax in the mid-1990s, where he recorded a series of albums with the band UNKLE. [40] The Kubrick exhibition was part of Lavelle’s ‘Daydreaming with…’ series; prior to Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick, Lavelle curated a show titled Daydreaming with James Lavelle (2010), followed by Daydreaming with Hong Kong Edition (2012). The intent behind the “Daydreaming with…” series is Lavelle’s desire to “marry music and the visual arts … to create a unique and multi-sensory experience, unprecedented by museum exhibitions or music festivals”. [41] There is an explicit intent in the project to subvert the museum exhibition experience with something original and innovative that provides, yet again, new perspectives.

Lavelle’s connection to Kubrick began as a teenage fascination with a VHS copy of 2001: A Space Odyssey and a bootleg copy of A Clockwork Orange. Lavelle has said his memory of watching these films is one of an “unmistakable feeling of awe” at the combination of music and imagery. [42] The influence Lavelle claims Kubrick has had over his own art and music was the motivation behind the exhibition, wanting to explore further the continuing legacy of the director. In the exhibition programme, Lavelle argues that Kubrick “inspired future generations of filmmakers and artists alike”. [43] A range of artists were briefed to respond to “either a theme, film, scene or character from the Kubrick archives, or the man himself”. [44] Not all the artists created new work, some were invited to present work they had previously created that was related to the exhibition theme, such as Jane and Louise Wilson’s Unfolding the Aryan Papers (2009), a film about the actress who was cast to play the lead in Kubrick’s unrealised “Aryan Papers”.

The exhibition is presented as an experiential narrative, at times immersive, inviting the audience to relive moments from the films, either by stepping into exhibits that recreate sets or props, or taking part in virtual reality. The Stanley Kubrick Archive itself is brought to life, and rather than revering archival objects as artefacts, they are contemporised and given momentum. The Wilson’s Unfolding the Aryan Papers, for instance, presents research photographs from the project, which are then seemingly animated as we see the actress Johanna ter Steege recreate the still images. Peter Kennard similarly contemporises the Stanley Kubrick Archive in his Trident; A Strange Love (2013-2016), having scanned documents and photography from the Stanley Kubrick Archive and digitally manipulated them. Kennard’s is a way of commenting on the continuing relevance of the themes of Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), juxtaposing images from the film with “world leaders charged with nuclear arsenals … he shows that the ghosts of the past still inhabit the present”. [45]

Though the contexts of history can be found throughout the exhibition, the narrative that is constructed is one of artistic inspiration, but once again rooted in fan desire to uncover the symbolism and hidden meanings of Kubrick’s work. Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard’s Requiem for 114 Radios exemplifies this, feeling like a recreation of the radio room in The Shining, being a “creepy, clever room that plays on the symbols and codes that often obsess Kubrick’s fans”. [46] Forsyth and Pollard take this obsession with codes to the extreme, using precisely 114 radio sets, a reference to the CRM 114 Discriminator device aboard the B-52 in Dr Strangelove. Kubrick fandom is the overwhelming thematic arc of Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick, often resulting in works that need explanation to the less than obsessive Kubrick fan. For instance, Stuart Hogarth’s Pyre (2016), a tower of electric fires, is an oblique reference to the burning down of The Shining set at Elstree Studios in 1979, a fact that has to be described in the exhibition program. These fan experiences are similarly evoked in Gavin Turk’s The Shining (2007), a mirrored maquette of the maze that features in the film and that sees many visitors looming over it to mimic the scene in which Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) stands over the toy maze. The exhibition evokes memories of the film and as the audience moves through the gallery, they are made to believe they are stepping into a corridor of The Shining’s Overlook Hotel, right down to the patterned carpet replicated on the floor (The Shining Carpet [WT], Broomber and Chanarin, 2016). The lighting is low and The Shining soundtrack reverberates around the halls, creating an immersive experience.

Richard Martin labels the exhibition “Stanley Kubrick’s worst nightmare”, saying that it is chaotically curated and rather than a day dreaming state, the exhibition is like a “nightmarish summer blockbuster: overblown, overhyped, and dominated by special effects”. [47] He indicates one of the key problems with the way Kubrick is exhibited is that emphasis is placed on the most iconic of Kubrick’s films – 2001, A Clockwork Orange, The Shining – to the neglect of the rest of his career. Martin justifiably claims that this reduces Kubrick’s career “to merely its most recognisable images: the monolith, the labyrinth, a black bowler hat”. [48] Nothing new is being added; it is merely a funfair of iconic pop imagery. It is about fandom, rather than any meaningful (re)interpretation, about creating experiential narratives that bring the audience closer to Kubrick and the films and re-consuming them in new contexts beyond which they were intended. Presumably, a portion of Kubrick fans would welcome this, the exhibition partly playing into a desire for more content, and more access to Kubrick the filmmaker. Fans often re-consume Kubrick’s films in a variety of methods to unlock their secrets, from watching The Shining projected with a version in reverse playing on top of it, to viewing the X-rated and R-rated versions of A Clockwork Orange simultaneously in split screen.

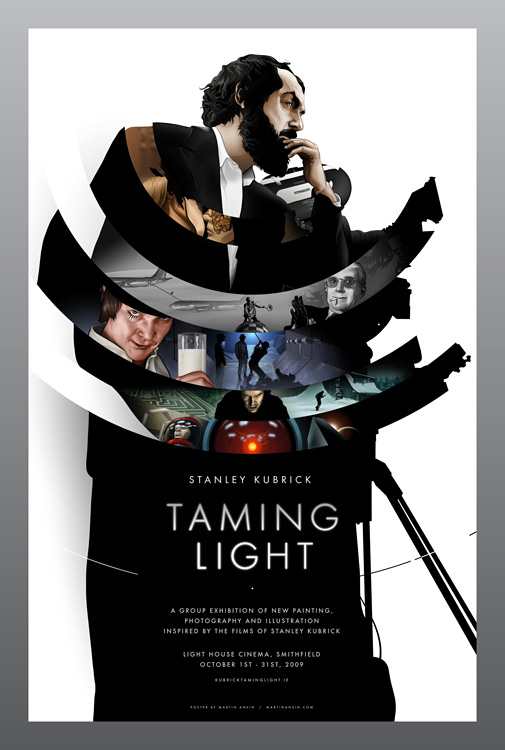

The contemporising of Kubrick by Lavelle has been seen before, notably Taming Light (2009), a “group exhibition featuring painting, photography and illustration inspired by the films of Stanley Kubrick”. Taking place at the Light House Cinema, Dublin in October 2009, it featured the work of 25 artists and was curated by film critic John Maguire. Maguire revealed his motivations for the exhibition as resulting from his Kubrick fandom and a desire to mark the tenth anniversary of the director’s death, “but in a way that showed how his images and the emotions they evoke are still with us”. [49] Maguire’s inspiration for the theme of the exhibition stemmed from graffiti he had discovered in Berlin of Jack Nicholson’s “here’s Johnny” grin in The Shining, combined with having seen an exhibition in Los Angeles, Remixing the Magic (2006), in which artists reinterpreted images of classic Disney characters. [50] Fan art, then, can be seen to have been a driving factor behind Maguire’s exhibition, featuring works such as a Doctor Strangelove with scantily clad women billowing out of his head, to the Paths of Glory (1957) trial rendered as a courtroom sketch. This fan celebration of Kubrick grows apace on the Internet, with numerous artwork that, often humorously, re-imagines the most iconic imagery of his films – Maguire himself has said that the exhibition was borne of a desire to demonstrate how “Kubrick is still alive for me, through his films, and how he lives on in the imaginations of creative people”. [51]

This contemporising of Kubrick sees fans seeking to revitalise and reveal the continuing relevance and newness of his work through pop art. This was the prominent motivation behind San Francisco’s Spoke Gallery exhibition Stanley Kubrick – An Art Show Tribute (2014). Over sixty artists, professional and amateur, reworked their favourite scenes and characters from Kubrick’s films into caricature, satire, abstract, and cartoon form. [52] A quick search on Google finds numerous sites on which fan art proliferates, from the creation of posters for unmade Kubrick films, to portraits that venerate Kubrick’s own image. A playfulness lies behind these works, as it does in Daydreaming. Far from being museum pieces, for Lavelle and co. Kubrick’s works continue to be fresh and vital and must be saved from being enshrined in glass casing.

Future Research

The above case studies are introductory research avenues for Kubrick scholars to further examine the way exhibitions are shaping the public narrative around the film director. There are the first signs that this is becoming a field of interest in “post”-Kubrick studies; scholars presented research in this area at the Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective (2016) conference, including Rafal Syska’s “Stanley Kubrick in the National Museum in Krakow” and Dru Jeffries ‘”Inside TIFF’s Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition”. [53] As these papers suggest, as well as this article, exhibitions large and small, historical and contemporary, continue to appear, if seemingly with reverential undertones. What can be detected in the curatorial motivations for these non-official exhibitions is a fandom intrinsically linked to the deification of Kubrick and his films. The curatorial narrative – the new perspectives – is one of re-consuming Kubrick’s films in new experiential contexts and of building on the auteur myth of Kubrick. This is achieved in one of two ways: either through the contemporising of his films and archive, reimagining iconic imagery into a new pop-art form, or by bringing audiences closer to his personal artefacts that are enshrined as historical relics and are imbued with scholarly importance – they are documents from which to unlock the hidden meanings of his films.

NOTES

[1] Disclaimer: I was a co-curator of Stanley Kubrick: Cult Auteur, along with Ian Hunter and Elizabeth Wheelband, with thanks to the assistance of Richard Daniels and Sarah Mahurter of the Stanley Kubrick Archives, and a special thanks to Jan Harlan.

[2] “Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition Press Release,” Contemporary Jewish Museum, 27 July 2016, http://www.thecjm.org/about/press/presskits.

[3] “Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition Press Release.”

[4] Lucian Robinson, “Cabinet of Curiosities”, Financial Times, (9 April 2011), p. 10.

[5] Frederic Raphael, “Stanley Kubrick, Museum Piece”, Commentary, Vol. 135, No. 4 (2013), p. 55.

[6] Raphael, “Stanley Kubrick, Museum Piece”, p. 56.

[7] Raphael, “Stanley Kubrick, Museum Piece”, p. 56.

[8] Arnie Cooper, “Wide-Angle View of a Director’s Life and Artistry”, Wall Street Journal, (31 October 2012), http://search.proquest.com/docview/1124482909?accountid=10472.

[9] Tatjana Ljujic, Peter Krämer and Richard Daniels, “Introduction”, in Stanley Kubrick: New Perspectives, eds. Ljujic, Kramer, Daniels (London: Black Dog, 2015), p. 13.

[10] Raphael, “Stanley Kubrick Museum Piece”, p. 14.

[11] Terry Smith, Thinking Contemporary Curating (New York: Independent Curators International, 2012), p. 30.

[12] Hans Ulrich Obrist, Ways of Curating (London: Penguin Books, 2014), pp. 22-23.

[13] Hans Ulrich Obrist, Ways of Curating, p. 23.

[14] Ljujic, Krämer, Daniels, “Introduction”, p. 14.

[15] Beryl Graham and Sarah Cook, Rethinking Curating (Cambridge, MIT: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2010), p. 11.

[16] “Most Popular Exhibitions,” Art Newspaper, Vol. 23, No. 256, (2014), p. 12.

[17] “Most Popular Exhibitions,” Art Newspaper, Vol. 25, No. 278, (2016), p. xv.

[18] Graham and Cook, Rethinking Curating, p. 10.

[19] Graham and Cook, Rethinking Curating, p. 10.

[20] Graham and Cook, Rethinking Curating, p. 10.

[21] Smith, Thinking Contemporary Curating, p. 35.

[22] Graham and Cook, Rethinking Curating, pp. 194-195.

[23] See Ian Hunter, Cult Film As A Guide To Life: Fandom, Adaptation and Identity, (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2016).

[24] “Stanley Kubrick: Cult Auteur Promotional Flyer”, De Montfort University, (2015).

[25] Hunter, Cult Film As A Guide To Life, p. 2.

[26] Hunter, Cult Film As A Guide To Life, p. 42.

[27] Hunter, Cult Film As A Guide To Life, p. 47.

[28] Hunter, Cult Film As A Guide To Life, pp. 53-55.

[29] Concept storyboards for Eyes Wide Shut, SK/17/2/10, Stanley Kubrick Archives (SKA), University of Arts London (UAL) (1996).

[30] Draft Eyes Wide Shut screenplay, n.d., SK/17/1/11, SKA, UAL.

[31] Eyes Wide Shut panel text, Stanley Kubrick: Cult Auteur, De Montfort University, (May-June 2016).

[32] “Stanley Kubrick: New Perspectives,” Aesthetica Short Film Festival, (2015), http://www.asff.co.uk/stanley-kubrick-new-perspectives-work-gallery-london/.

[33] “Stanley Kubrick: New Perspectives.”

[34] See Kate Egan, “Precious footage of the auteur at work: framing, accessing, using, and cultifying Vivian Kubrick’s Making The Shining”, New Review of Film and Television Studies, Vol. 13, No. 1, (2015), pp. 63-82.

[35] Egan, “Precious footage of the auteur at work”, p. 66. See also David Church, “The Cult of Kubrick”, Offscreen.com, (2006) http://offscreen.com/view/cult_kubrick.

[36] “Exhibition Stanley Kubrick Photographer,” Brussels Life (2012), http://www.brusselslife.be/en/article/exhibition-stanley-kubrick.

[37] Joseph Addison, The Works of Joseph Addison, (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1837), p. 479.

[38] Two key examples are Nathan Abrams, “An Alternative New York Jewish Intellectual: Stanley Kubrick’s Cultural Critique”, in Stanley Kubrick: New Perspectives, eds. Tatjana Ljujic, Peter Krämer, and Richard Daniels, (London: Black Dog, 2015), pp. 62-79, and Geoffrey Cocks, The Wolf at the Door: Stanley Kubrick, History, & the Holocaust, (New York: Peter Lang, 2004).

[39] Main biographical panel text, Stanley Kubrick: Cult Auteur, De Montfort University, May-June 2016.

[40] Emily Yoshida, “The rise of Mo’Wax founder James Lavelle – and the record industry that fell with him”, The Verge, (29 March 2016) http://www.theverge.com/2016/3/29/11320786/artist-and-repertoire-dj-shadow-documentary-interview-unkle-sxsw-2016.

[41] “Somerset House Press Release: Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick”, Somerset House (2016).

[42] Rob Hinchcliffe, “What you need to know about James Lavelle’s Stanley Kubrick Exhibition”, Highsnobiety, (2016), http://www.highsnobiety.com/2016/07/20/james-lavelle-stanley-kubrick-exhibition/.

[43] Introduction, Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick, exhibition program (2016)

[44] Introduction, Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick.

[45] ‘Peter Kennard’, Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick.

[46] Richard Martin, “Is this exhibition Stanley Kubrick’s worst nightmare?”, Apollo, (12 August 2016) http://www.apollo-magazine.com/is-this-stanley-kubricks-worst-nightmare/.

[47] Richard Martin, “Is this exhibition Stanley Kubrick’s worst nightmare?”.

[48] Richard Martin, “Is this exhibition Stanley Kubrick’s worst nightmare?”.

[49] John Maguire, “Stanley Kubrick: Taming Light”, http://maguiresmovies.blogspot.co.uk/2009/09/stanley-kubrick-taming-light.html?m=1.

[50] Disney sponsored the exhibition, despite the artists openly reclaiming characters that had become corporate symbols.

[51] Email correspondence between the author and John Maguire, (6 October 2016).

[52] Ehud Riven, “12 Artworks Inspired by Stanley Kubrick Films”, Walyou, (15 September 2014) http://walyou.com/stanley-kubrick-films-fan-art/.

[53] Rafal Syska, “Stanley Kubrick in the National Museum in Krakow”, conference paper, Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective, De Montfort University, Leicester, (May 11-13, 2016); Dru Jeffries, “Inside TIFF’s Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition”, conference paper, Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective, De Montfort University, Leicester, (May 11-13, 2016).