一个和八个

Guo Xiaochuan 郭小川 (1919-1976) |

2015 edition of “The One and the Eight” |

Guo Xiaochuan’s (1919-1976) poem “The One and the Eight”, written in 1957, has subsequently been adapted as a film that was released in 1984, and a thirty nine episode series first broadcast on Chinese television in 2015. The storyline is simple. Set in northern China in 1941 at the height of the Anti-Japanese War (1937-45), Guo’s poem tells the story of Wang Jin, an instructor in the Eighth Route Army. Wang is the subject of a malign accusation of treachery and, as a consequence, is incarcerated with a motley bunch of deserters and bandits. Remaining steadfastly loyal to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) throughout, Wang eventually attains redemption by showing supreme courage in a battle against the invading Japanese force, while at the same time encouraging his fellow prisoners to change their ways and devote themselves to fighting for the nation. Guo Xiaochuan’s poem, which offers the bare bones of a story of mistreatment and injustice, ends with the protagonist selflessly serving the nation at a moment of great danger.

Such a poem should have been safe political territory for Guo Xiaochuan, since writing about the Anti-Japanese War was central for all forms of cultural production in Maoist China, and, as the making of the recent TV series demonstrates, has remained so ever since. However, in spite of what appears on the surface to be a conventional storyline, complete with a redemptive ending, the history of the creation and publication of Guo’s poem was far from straightforward: it was not considered suitable for publication at the time of writing, only appearing in print for the first time in 1979, shortly after his death. The controversy stemmed from the novelty of the protagonist suffering a miscarriage of justice despite being a member of the revolutionary troops: any suggestion that a loyal member of the CCP could have endured mistreatment at the hands of the Party was asking for trouble.

The making of the film, in addition, was extremely convoluted: when the first, unremittingly bleak, version was submitted for review in late 1983, there followed a series of negotiations that would last around a year before its eventual, brief, release in late 1984. Analysis of the recent production of a TV series based on Guo’s poem reveals a very different picture. In contrast to the austere film version, the producers adopt an uncomplicated style, backed up by a substantial budget that is manifested most strikingly in the elaborate mise-en-sc?ne employed to depict the comfortable lifestyles of both the occupying Japanese officers and their Chinese collaborators. The adaptation is well crafted, with careful attention to both characterisation and dramatic structure. Although many of the tropes of the war with Japan that feature so prominently in a range of artistic forms and genres are present in the poem, the film and the TV series, very different visions of the conflict are presented.

Guo’s poem and its subsequent adaptations repay close examination for several reasons. Firstly, while the 1983 film version has received some attention due to its iconic status as the first film made by the Fifth Generation directors, there has been little discussion of either Guo’s poem or the more recent TV drama series. Secondly, cultural productions about the Anti-Japanese War, which were ubiquitous in the Maoist era, continue to feature prominently today. From films and novels to poetry and visual art, not only are new stories being written, but many favourites from earlier times, the so-called “Red Classics,” are still being revived. The TV series is of interest precisely because neither Guo’s poem, nor the film adaptation, fits easily into the Red Classic genre: after all, the original poem was not published till after Guo’s death, and Zhang’s film was awarded only the briefest of cinematic releases. As will be demonstrated below, the version of the story that appears in the TV series has gone through a process that I will call Red Classicisation.

Thirdly, while the theme of the Anti-Japanese War may have remained in vogue over the course of modern Chinese history, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has seen a steady stream of policies and campaigns, to which writers and filmmakers have had to adapt. The three versions of ‘The One and the Eight’ to be discussed were affected variously by the Hundred Flowers and Anti-Rightist campaigns of the mid to late 1950s, the cultural renaissance of the early 1980s, and the ongoing interference in cultural production affecting market reform era China in the second decade of the new millennium. As well as having to conform to the correct political message of the time, the producers of the TV series now have to satisfy the demands of the marketplace.

The One and The Eight (Zhang Junzhao, 1983)

In the TV series, key elements of the melodramatic form, namely undiluted good communists and out and out villains, as well as a redemptive ending, are interwoven with the need to reflect contemporary political standpoints. Marcia Landy has described how melodrama is employed as an essential ingredient for the creation of consensus, through the depiction of conflicts over power, legitimacy and identity, involving scenarios of physical and spiritual struggle and an intense concentration on belonging and exclusion. [1] Guo’s poem provided the narrative framework for not just an experimental film but a conventionally melodramatic TV series. Analysis of the three versions of “One and the Eight”, then, provides the opportunity to examine the shifting sands of what has, and has not, been possible for writers and filmmakers in China over a time-span of almost sixty years.

Guo Xiaochuan (1919-1976)

Like many other Communist sympathisers, Guo spent the war years at the CCP base camp in Yan’an and by 1949 he was working for the Party’s news and propaganda ministry. In the early years of Communist China the independence of all writers was severely tested, as they were subjected to a succession of campaigns, the most significant of which for this piece were the Hundred Flowers Movement (1956-7) and the subsequent Anti-Rightist Campaign (1957-8). The former movement serves as an example of a thaw, when writers, accustomed to producing works to order, were encouraged, albeit for a short time, to point out the Party’s shortcomings, while the Anti-Rightist Campaign was a severe clampdown on those very writers who had been brave, or foolish, enough to speak out.

Guo Xiaochuan attained fame for writing in a style known as political lyrical poetry that was influenced by the Soviet revolutionary poet Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930). According to Hong Zicheng, political lyrical poetry is a form in which the poet appears as the mouthpiece of a class expressing emotional responses to, or opinions on, important contemporary political events or trends. [2] Guo Xiaochuan first came to national prominence in the mid 1950s, attaining recognition for long narrative works such as “Song in Praise of Snow”, “Stern Love” and “Triptych for a General.” In April 1957, during the Hundred Flowers Movement, he published “Deep Mountain Valleys” about a despairing intellectual who commits suicide. Although “The One and the Eight” was not considered fit for publication at the time of writing, a later work called “Looking at the Stars” was published in 1959: an article published in Wenhuibao not long afterwards criticised Guo for contrasting the eternity of nature with the transience and futility of human existence. [3] These were dangerous accusations in Maoist China. In spite of the banning of “The One and the Eight” and the criticism of “Looking at the Stars”, however, Guo continued to write. Xing Xiaoqun suggests that the reason Guo did not suffer more drastic treatment was that he remained in favour thanks to his participation in the anti-Hu Feng campaign of 1955. Indeed, Guo held the position of secretary-general in the Chinese Writers’ Association. [4] An edition of his collected works was published three years after his death in 1976.

The poem

In a diary entry for 24th April 1957, around the time of the publication of “Deep Mountain Valleys”, Guo noted that he was thinking about writing “a tragic poem about a revolutionary.” In terms of his own experience it is worth noting that, during his time in Yan’an, his wife, Du Hui, spent more than two years in prison and Guo was acquainted with Wang Shiwei, who was criticised and subsequently executed for writing articles deemed to be anti-Party. Inspired, perhaps, by the liberal atmosphere of the Hundred Flowers movement, Guo said he wanted to say what other people did not dare to. [5] According to his son, Guo Xiaohui, Guo Xiaochuan wrote the first draft of “The One and the Eight” from 19 to 26 May 1957, and revised it in the autumn of that year, extending its length from 1,200 to 1,686 lines. [6] Hong Zicheng notes that critical attacks on the poem were restricted to the leadership levels in literary circles. [7] The longer version was published in 1979 in the journal Yangtse River Literature and appeared in book form in 2015, after the broadcast of the TV series.

The poem is divided into eight sections, each made up of stanzas of six lines, plus a short coda. Each section has a title: the first, for example, which is titled “An arrogant prisoner”, introduces the central character of Wang Jin. Lines vary in length with no set pattern from one six-line stanza to the next. The war most often takes place off stage, the prisoners’ reveries, for example, being intermittently interrupted by the sound of gunfire. Tianjin, where Wang Jin had worked in the city’s docks, is the only precise location in the poem. Apart from Wang Jin, the group of prisoners includes one who is suspected of being a spy for the Japanese, three hardened bandits and four army deserters, making Wang the one and the others the eight. Apart from Wang Jin, most of the others are shadowy figures, with only three of them given names, and then only in relation to their physical characteristics: Pointy Chin, Big Whiskers, and Rough Eyebrows. Of these the latter two are most clearly delineated, their characters displaying a combination of aggression and sullen taciturnity.

By way of contrast, there are extensive details about Wang Jin who recounts his personal history to his fellow prisoners at some length in the third section of the poem, “A strange case”: we hear of his work in the Tianjin docks and as an army instructor, and how he fell out of favour after being accused of collaborating with the Japanese. The other prisoners, who had initially been hostile towards Wang, are eventually won over by his consideration for others, when, during a forced night march, he carries several of their bags. Prepared now to listen to his story, they come to accept that what they had thought of as arrogance was rather wounded pride. He tells them at length of his undying loyalty to and love of the Party.

There are several passages in which Wang and others speak but the poem is largely descriptive. Apart from isolated references to the weather or the landscape, much of the text is taken up with lengthy sections describing the gloominess of the prisoners’ surroundings and the mostly silent atmosphere which envelops them. At times, Guo uses a narrator who relates the prisoners’ feelings and interjects intermittently with comments on proceedings:

‘Oh, Wang Jin, are you really so foolish?

They’re making fun of you.

How can you endure such humiliation?’ (pp. 20-1)

On occasions, the narrator addresses the reader directly, in a way similar to traditional Chinese story-telling. In the seventh section, “On the gallows”, for example, he poses the question “Ah, readers, you are surely concerned about the instructor/What sort of expression does he have?” before going on to answer “Quietly lowering his head like a silent sculpture/Neither trembling, nor sorrowful/Seemingly at peace” (p. 69) There are also some more elegiac passages:

Oh! China’s golden plains.

As soon as I see you I think of your tomorrows.

May the tractors roam about at will,

May this empty space be filled with the fragrance of fruit.

It’s not the case that I’m fed up with this holy war

More that I dislike the dust and smoke of gunfire (p. 67)

At one point, Wang Jin delivers a homily to his fellow prisoners which is very much on message:

You’ve all suffered more injustice than I have

You didn’t start out bad, you were corrupted by a rotten society

If you were to die at the same time as the rotten society

In the end you should understand that it is your sworn enemy (p. 46)

When he is first placed in the prison, Wang Jin is tormented by a sense of injustice at the way in which he has been treated while also feeling aggrieved to be linked in any way with common criminals. He is the agent of change for the renegades, bringing them hope, like the tide of life surging into eight heavy, weary souls (p. 24) According to Xing Xiaojun, Guo Xiaochuan was na•ve to think that such a poem would be published. As Xing points out, “The One and the Eight” was broaching new territory, in particular with the idea that the CCP was capable of making mistakes. V [8]

The film

Although much less well-known than Yellow Earth, the film that signalled the start of the international impact of the group that came to be known as the Fifth Generation filmmakers, The One and the Eight is not only their first film, but, in many ways, stands as the most forthright example of their iconclastic aims and methods. [9] The first fruit of a scheme whereby the initial batch of graduates of the re-opened Beijing Film Academy (BFA) were assigned to work in provincial film studios, The One and the Eight was made by the youth unit of the Guangxi Film Studio. [10]

Zhang Junzhao, the film’s director, and Zhang Yimou, the cinematographer, were both graduates from the BFA. Given the fact that Zhang Yimou has gone on to have a hugely successful international career, while Zhang Junzhao, in comparison, faded into obscurity, it is tempting to attribute the film’s revolutionary and challenging visual style to the former rather than the latter. It is certainly very much the case that the film is discussed today more in terms of Zhang Yimou’s contribution. [11] In fact, even in the early discussion of the film he it was who came up with noteworthy comments about the process of filmmaking, saying, for example, “I was filled with anger whenever I set up the camera. All of us were basically fed up with the unchanging, inflexible way of Chinese film-making, so we were ready to fight it at all costs in our first film Éthe point was simply and deliberately to be different.” [12] The aim, as Paul Clark noted was to confront “the aesthetic concern for beauty which in much of Chinese film history had been an excuse for contrived unnaturalness.” [13] Much of the composition was deliberately asymmetrical and unbalanced, with actors placed to one side of the shot or even obscured by scenery, in order to draw viewers’ attention to the visual aspects of the film rather than the script.

From today’s standpoint it is hard to imagine quite how new The One and the Eight must have appeared at the time for a Chinese audience. Historical films of the Maoist era routinely started with some heavy-handed contextualisation about the period in question, usually in the form of an off-screen narrator giving background information. Here, as the opening credits roll, a series of black and white photographs reveals images of the war, followed by close-ups, also in black and white, of the leading figures in the film. The opening sequence, of the camera slowly panning up the walls of the pit that is serving as a temporary prison towards the sky, is startlingly dark. The nine prisoners appear slowly out of the gloom, creating an oppressive atmosphere that persists throughout the film. While Wang Jin is named, the eight remain shadowy figures, with only Eyebrows retaining his epithet from the poem, the others referred to only by names such as Little Dog, or Baldy. The officer in charge of the prisoners has no name, the medical officer is only given her title while the spy and the well-poisoner appear in the credits without personal names. Overall, the atmosphere is extraordinarily downbeat, Ni Zhen commenting on an overwhelming feeling of desolation and solemnity. [14]

In terms of both style and content, the rawness of the film is still shocking in spite of several enforced changes, the most significant of which concerned a moment in which a female army officer was on the point of being raped by a group of Japanese soldiers. In the original version, the woman was shot by an old bandit in order to prevent her falling into the hands of the rapacious Japanese. Instead, the final version of the film shows the old man shooting at the soldiers. [15] An indication of the debate that took place among those who took part in the film’s official review process is apparent in the words of the veteran film critic Zhong Dianfei, who complained that film criticism in China was too often in the hands of politicians and officials: “When the situation got out of hand, to defend the movie became tantamount to defending brigands. The other reviewers, including myself, found it difficult to do anything for the film, because to defend it meant, after all, to get too close to the gate of hell.” [16]

As Rodekohr notes, the film confronts the revolutionary myths that had sustained Chinese filmmaking for so long: the positive portrayal of characters who would previously have been seen as irredeemable renegades went against the old certainties of Maoist era filmmaking. [17] Furthermore, the filmmakers broke long-standing rules of Chinese war films according to which all freedom fighters who develop political consciousness must be drawn into the ranks of revolutionary forces. [18] Any filmmaker of the time was aware of the constraints, both spoken and unspoken, regarding what they could do. The film was the product of a short-lived moment of relative artistic freedom when subject matter such as the Anti-Japanese War could be presented in more subtle and challenging ways: with hindsight it is possible to see that these were the dying days of the old system of film production being placed exclusively in the hands of the monolithic state-funded studios.

TV production in general

Before looking in detail at the most recent adaptation of Guo’s poem, I will first provide some background on the phenomenon of the drama series which have increasingly formed a staple feature of viewers’ habits in China over the last thirty years. The development of TV drama has been described by several scholars, from its origins in the late 1950s through to the recent explosion in terms of quantity. In recent years attention has turned from general surveys to close examination of the different genres that have prevailed. Zhong Xueping, for example, looked at series covering various dynastic struggles of the Imperial period, while Ying Zhu and Bai Ruoyun examined the genre of anti-corruption dramas. [19]

Although the popularity and acceptability of certain topics fluctuate to a certain extent, the Anti-Japanese War has remained a constant. In recent years there has been a proliferation of such series, including many adaptations of well-known films such as Little Soldier Zhang Ga (1961) and Landmine Warfare (1962), as well as Zhang Yimou’s directorial debut Red Sorghum (1988): there has even been a cartoon version of the Cultural Revolution children’s film Sparkling Red Star (1974). While most of these works can be categorised as Red Classics, the adaptation of The One and the Eight is on the surface more surprising, because, if the story was familiar at all, it would have been from the original film which was so abrasively experimental.

Gong Qian has noted the deployment of two main narrative strategies in the contemporary rewriting of texts from earlier periods of Communist China, namely the humanising of not just the heroes but also the enemy, as well as the construction of romantic relationships between the heroes and heroines. The production of such series has been subject to state control, with the State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT) closely involved in the monitoring of production. [20]

The ways in which the stories are told have also changed. In an examination of a twenty episode remake of The Red Detachment of Women (Xie Jin, 1960), among the most famous of all the films of the Maoist era, Rosemary Roberts outlined the marginalising of class issues with the proletariat no longer at the centre of events and the bourgeoisie no longer vilified. [21] Elsewhere, Michael Berry has examined in detail one series, Scarlet Rose: the Goddesses of Jinling, set against the background of the Nanjing Massacre, which was broadcast from 2007 to 2008. Here was a vision of the war years that was radically different from the one that was so familiar to those who grew up in China in the 1950s and 60s. Rather than showing the Chinese population as victims of the vicious marauding Japanese invaders, Scarlet Rose depicted a group of female vigilantes who were themselves the aggressors, terrorising the occupying force.[22] Mou Zaijiang noted that around half of the more than three hundred TV dramas broadcast in 2012 were about recent revolutionary history, and of this figure the majority were based on the Anti-Japanese war. He commented that the fresh style of the series was proving popular, attributing the success to three factors: the inclusion of kung fu style fighting, the casting of attractive, youthful stars on the Chinese side, and the contrasting portrayal of Japanese soldiers as ugly, their clothes awry, with little moustaches on their evil faces, in other words exactly as they had been depicted back in the Maoist period. [23] Such series full of fanciful and fantastic elements led to the coining of the term kangri shenju (Sacred Series of the Anti-Japanese War).

More recently there has been a reaction against the style of the kangri shenju. Li Guocong, for example, listed what he saw as the generally poor standard of the series, bemoaning preposterous incidents such as single grenades bringing down Japanese war planes, and noting that any popular series would soon be followed by a succession of poor imitations. [24] Underlying such comments, of course, is the impact of commercial considerations on the production of TV drama series. What the makers of the TV adaptation of ‘The One and the Eight’ had to take on board was not the political message, which remained largely unchanged, or the predominance of the melodramatic form, but rather the production of a series that was required to achieve commercial success. In an age of diverse choice and an audience that is far removed from those who watched television in earlier periods of Communist rule, there is a need to attract and hold viewers. In particular, the received wisdom is that a love interest is now required.

The TV series of The One and the Eight

Directed by Cao Huisheng, the TV series based on Guo’s poem was made in 2013 and broadcast in March 2015. [25] Given the amount of time available, and the relative shortness of the original poem, a substantial amount of additional information about the individuals who are to become the one and the eight is required in order to fill out thirty-nine episodes. The series is set in Hebei in northern China during the Anti-Japanese War, though at no time is any indication given of the overall state of play of the war and, apart from a few references to characters heading off to Yan’an, precise locations are not given. After seizing Pang Wenxuan, a former officer of the Nationalist Party (KMT) now working for the occupying Japanese, Wang Jin, an instructor in the Eighth Route Army, is in turn captured by the Japanese. Following lengthy interrogation at the hands of the now released Pang, Wang Jin, along with several other Eighth Route Army Soldiers, is bound and put on a boat from which they are all thrown into a river. All the men drown apart from Wang Jin, who survives because one of his fellow prisoners had bitten through his ropes enabling him to swim ashore, where he is discovered by Qishu, a peasant, and his grandson Xialong who look after him while he recovers from his ordeal. [26] He subsequently returns to the Eighth Route Army where he soon falls under suspicion for being a spy, partly after being denounced by another traitorous Chinese, and also because his escape seems so fanciful and there is no one who can verify his story.

The One and The Eight (Cao Huisheng, 2015) – DVD boxset |

The One and The Eight (Cao Huisheng, 2015) – News conference |

After lengthy investigation, he is put in prison together with three deserters, three bandits, a well poisoner and Manniu, a young woman who, after being orphaned at a young age, had been adopted by the Pang family, whose intention was to marry her off in due course to the family heir Pang Wenxuan. [27] While away studying in Japan, however, Pang Wenxuan not only agrees to work for the puppet government in China, but becomes engaged to Wuwei Hezi, a Japanese woman who is the younger sister of a senior Japanese officer. While Manniu is shocked to see that she has been usurped, she initially remains loyal to the Pang family. After being led to believe that Wang Jin has killed Pang Wenxuan, Manniu joins the anti-Communist forces organised by the Japanese, prior to going undercover in the Eighth Route Army base camp in order to gain revenge by killing Wang Jin. In due course, she is able to join the Eighth Route Army, thus allowing her to stay in the camp and develop a relationship with Wang Jin. It is after she is discovered transmitting signals to the Japanese that she is imprisoned together with Wang Jin and the others: he is the one and the others make up the eight.

Prolonged discussions among the leadership of the Eighth Route Army about what to do with the prisoners follow. Eventually, the well poisoner is executed and one of the deserters, who turns out to be spying for the Japanese, is shot when he attempts to flee. The remaining prisoners are eventually released to join the struggle against the advancing Japanese army. When the group is trapped on top of a hill by the Japanese, the wounded among them die a martyr’s death by blowing themselves up at the moment when the Japanese soldiers arrive, thus inflicting heavy casualties. The series ends with Wang Jin, Manniu, Xiao Shengzi, the one remaining deserter, and Zhao Wang, an ordinary soldier, at the top of the cliff awaiting seemingly certain death when a division of the Eighth Route Army arrives in time to save them.

Opening Credits |

First and final episode |

In fact, the scene of the four at the cliff top has already been shown in the opening moments of the very first episode, followed shortly afterwards by scenes showing Manniu’s upbringing with Pang Wenxuan’s family, as well as the shameful time she spent spying for the Japanese. A caption then informs the viewer that the action is going back several months earlier. Any tension about the long sections of the plot that cover Manniu’s attempts to kill Wang Jin, as well as his own perilous status as a suspected traitor, is thus dispelled from the start. Indeed, in order to ensure that there is no doubt that Manniu is not a bad character, her smiling face features early in the opening credits of each episode, immediately after a shot of Wang Jin shooting at the Japanese, a look of angry determination on his face. There is thus no question of whether Manniu will switch allegiance or whether Wang Jin will escape execution as a traitor; the viewer is, rather, waiting for these events to occur. The music of the theme song which accompanies the credits is alternately stirring and sentimental, the words blandly aspirational:

A gale is blowing across the plains

Never has there been such passion for the nation

With swords out of the scabbards

Marching forward to the sound of drums

Certain key melodramatic triggers are thus put in place in order to guide the audience towards an understanding of which characters to follow.

From the start, the contrast with Zhang Junzhao’s film is clear, the sense of darkness and gloom that so permeates his work no longer present. Apart from the internal shots of the cell in which Wang Jin is detained along with the other eight prisoners, the Eight Route Army camp is invariably bright, and even the cell is nothing like as oppressive as the pit in which the men are located at the start of the film version. The iconic image that came to symbolise Zhang Junzhao’s film, of the nine men tied to each other with a rope, appears only briefly, when the prisoners are placed inside a mountain cave.

Wang Jin

Above all, the TV series tells the story of Wang Jin. His is the first face we see in the opening credits, and he remains indomitable and incorruptible in the face of everything that is thrown at him. His character is established in the opening minutes of the first episode, when not only does he display compassion towards his fellow soldiers, but, when the Japanese attack, acts decisively and supremely brave. Wang Jin is portrayed by Zhang Tong, an actor whose lead roles in earlier series about the Anti-Japanese War ensured that he was already familiar to audiences. As Wang Xin commented in an online publicity piece, “over the last eleven years he has displayed the daily maturing of his acting skills by means of a classic TV image, creating a man of steel forging an eternal memory for his audience.” [28] The familiarity of the lead actor is indicative of the importance of commercial considerations and the need to cater for audience expectations.

Wang Jin and Manniu |

Wang Jin and He Cuiying |

Apart from his many oral defences of his integrity, Wang Jin regularly displays great bravery, on more than one occasion single-handedly fighting off several armed attackers. A more modern aspect of Wang Jin’s character is shown after Lao San, the brashest of the three bandits, has spoken towards Manniu in vulgar terms: Wang Jin stands up for Manniu, saying “Whatever the merits of the case, I will not put up with you abusing a woman.” She is surprised by this, and the incident can be seen as the start of her changing her attitude towards him. He also treats Pang Wenxuan humanely, and with respect for the law, when he captures him at the start of the series: in spite of his contempt for Pang’s actions, he chooses not to execute him on the spot because he feels that Pang should first be interrogated by the people.

A substantial part of the series is taken up with a protracted investigation into the question of Wang Jin’s supposed treachery. Meng Zhenfei, the officer in charge of the investigation, is severe but fair, allowing Wang to respond to the allegations over the course of several interviews. In terms of the dramatic construction of the series, this device provides repeated opportunities for Wang to deliver homilies about his undying loyalty to the CCP and his desire to kill the traitorous Pang Wenxuan. Eventually, Meng Zhenfei is sufficiently moved to order the halting of the planned execution of the prisoners. At that moment the Japanese attack arrives in the village and everything changes. Wang Jin calls for patriotism, drumming into his fellow prisoners, whose lives up to then have been dominated by self-interest, the need for self-sacrifice. The big confrontation arrives in the final episode: having told Pang how he will marry Manniu and they will have children and grandchildren who will not be tricked by the Japanese, Wang Jin duly kills him, with the sound of the series theme tune in the background.

Other male characters and the notion of haohan

The first episode introduces the leading figures including a group of bandits, three of whom will constitute part of the group of eight prisoners. The actions of the bandits raise questions about the portrayal of masculinity and morality. When two of them are brought in for questioning by one of the Eighth Route Army officers and given a lecture about their evil preying on the common people, the response of their leader, Lao Er, is to point out, “We may be bandits but we’re righteous bandits: we cannot live with the Japanese dwarves.” The message is clear: they may be tough, but underneath the bluster they are patriotic rough diamonds. This is closely linked to the notion of haohan (tough guys), critical for an understanding of male culture, which features at a key moment in Guo Xiaochuan’s poem when Wang Jin accuses his fellow prisoners of causing trouble for the masses and the Eight Route Army when they should be fighting the Japanese devils:

You’re a bunch of bandits, traitors and deserters

Who have all truly had hard lives.

You act as bandits, but reckon you’re haohan;

In reality, haohan should always work for the people. (pp. 40-41)

|

|

| Three bandits, three deserters and a well poisoner |

More recently, Geng Song has written of a recent revival of the haohan spirit, noting such features as a lack of discipline and a love of violating rules. [29] In the TV series there are very clear echoes of the idea of a coming together of a band of haohan, as seen in the early vernacular novel The Water Margin, particularly in the prison scenes: moved by the stirring words Wang Jin has uttered, his fellow prisoners proclaim his innocence, describing him as haohan. This admiration culminates in the moment when Wang, on the point of being taken away for execution as a traitor, asks his fellow prisoners to repeat a phrase after him. When Xiao Shengzi suggests “Twenty years from now, let us return as tough guys”, Wang Jin responds with a declamation of a chorus of “Destroy the Japanese invaders, give us back our rivers and mountains.” As the other prisoners join in and they all repeat the words over and over, the theme song of the series appears on the soundtrack along with a montage of scenes of fighting from earlier episodes in which we see repeated evidence of Wang Jin’s supreme bravery. The unfolding of the storyline sees the transformation of a disparate bunch of individuals into staunch patriots accepting of the need for the values, and rules, of the CCP. What they require is guidance in how best to serve the state and this has to come from following the example of Wang Jin. Just as was the case in both Guo Xiaochuan’s poem and Zhang Junzhao’s film, initial suspicions give way to admiration.

Unlike the poem and the film, the eight prisoners are all given names, the format of the series allowing time for the establishment of rounded characters. The only irredeemably bad characters are the well poisoner Hao Ren and the traitorous Lao Sun. Hao Ren is decapitated in episode 26 and Lao Sun is shot in episode 28, leaving leaves the way for five of the remaining six prisoners to die heroic deaths over the course of the following episodes: by the end of the series Xiao Shengzi is the only one of the eight to have survived. He is presented as a na•ve young man led astray by older more devious accomplices; his survival at the end of the series signals the importance of youth and hope for the future.

What, then, about the very different Pang Wenxuan, the one who was led astray? The clash between Wang Jin’s honesty and integrity and Pang Wenxuan’s duplicity is a key component of the melodrama. The two had once been comrades in the Eighth Route Army, but Pang joined the KMT while he was in Japan. Once back in China, he boasts to Manniu of his contempt for the Communists, saying “However many Eight Route Army soldiers I have killed it’s not enough” and displays cold cruelty to the prisoners on the boat. However, there are moments when we see a more nuanced picture of Pang, notably in a brief flashback to his period of study in Japan which reveals him to be na•ve and thus easily corrupted by his Japanese hosts. So the trend towards the humanisation of dramatic characters, described by Gong Qian and others is evident, the longer format of the TV series allowing time for greater depth of characterisation. This will be seen again later in the discussion of the portrayal of the bourgeoisie.

Female characters

Where Guo Xiaochuan’s poem has no female characters and Zhang Junzhao’s film contains only the medical officer, the television series takes a very different approach with the foregrounding of the central love interest of Wang Jin, and his relationships with both Manniu and his fiancée He Cuiying, reflecting the very different requirements of contemporary television drama. The characterisation of He Cuiying is uncomplicated and from her first appearance in the opening episode, when she stands in dappled sunlight with Wang Jin, highly sentimentalised. She is selflessly devoted to her work as a nurse for the army and welcoming towards Manniu following her arrival at the army base.

Pang Wenxuan |

Wuwei Hezi |

In fact, following his return to the Eighth Route Army base, Wang Jin spends considerably more time with Manniu than he does with Cuiying and the love interest is gradually played up, leading to the emergence of areas of conflict between the two women. Eventually, after overhearing others talking about the close relationship that has developed between them, Cuiying, worried that Manniu and Wang Jin are falling in love, asks Manniu whether she loves Wang Jin, and offers to leave if that is the case. Manniu says that it was Wang Jin who awakened her from the lies of the Japanese and made her realise that she was a Chinese person. Cuiying is shot by a Japanese soldier very soon after this discussion, and dies in Wang Jin’s arms, telling him in her final words that Manniu could now look after him. With Cuiying off the scene, the story can now move towards the ending scene previewed at the start of the first episode.

There are several signals to the audience that Manniu is not irredeemably bad, but rather a victim of the oppression suffered by women in pre-communist China, as a result of her status as a woman whose marriage has been arranged without her having any say in the matter. Crucially, one of the Japanese officers lies to Manniu, informing her that Pang Wenxuan has been killed by Wang Jin in order to ensure that she will be prepared to assassinate Pang. Fuelled by anger, Manniu infiltrates the Communist Army base with the intention of killing Wang. Following her acceptance into the Eighth Route Army, Manniu is able to spend time with Wang Jin, her bourgeois background allowing her to guide him towards an understanding of traditional Chinese culture.

The most overt signal that viewers’ perceptions of Manniu should be sympathetic comes when Meng Zhenfei announces that her parents were revolutionary martyrs killed in Shanghai in 1927 by the KMT, thus guaranteeing her a perfect political background: this information is repeated several times. It later transpires that her parents were intellectuals. In the same way that the bandits need to benefit from the wisdom of the CCP in the physical form of Wang Jin, so Manniu requires him to enlighten her about the evils of the Japanese, and, by association, the collaborator Pang Wenxuan. Thrown together with Wang Jin for long periods, Manniu comes to realise that he is a good person, moving from hatred of the man she believes has killed her intended husband to love for the incorruptible CCP instructor.

The importance to contemporary, audience-chasing, dramas of softer, more sentimental plot elements, embodied by female characters, is further evident in the relationship between Manniu and Hong Furen, the wife of a local police chief, who on the surface is assisting the occupying Japanese army in Shicheng, a town near the Eighth Route Army camp, but is in reality an underground worker for the Communists. Having been brought together after Manniu’s arrival at the Communist base camp when she is assigned to look after the pregnant Mrs Hong, the two women become close friends. Eventually they discover that they are sisters, the link revealed when they realise that the two pieces of jade they own separately are two halves of the same ornament, broken many years previously.

The bourgeoisie and traditional values

Class issues featured prominently in depictions of the Anti-Japanese War produced during the Maoist period. In the TV version of The One and the Eight, in contrast, the downplaying of the suffering of the ordinary people and the matching upgrading of the bourgeoisie, noted by Rosemary Roberts in the TV remake of The Red Detachment of Women, are again present. This is not to say that there are no instances of victimisation of the common people: scenes of the slaughter of villagers by the Japanese army occur sporadically, and Meng Zhenfei delivers a stern lecture to the bandits on their rapacious exploitation of the masses, but the sympathetic portrayal of what might be called the good bourgeoisie is conspicuous. We have already noted the revelation of the information that Manniu’s parents were bourgeois intellectuals: of equal interest is the case of Pang Shengqian, Pang Wenxuan’s father.

When we meet Pang Shengqian in the first episode, it is as the head of a family that lives comfortably. He is, moreover, a patriot who is ashamed of his son’s collaboration with the Japanese occupying force: he tells him how he worships at the clan altar in an attempt to appease the family’s ancestors who have never taken up weapons, and asks him to kneel down to atone for his lack of filiality. He refuses to attend his son’s wedding to Wuwei Hezi and is very unhappy to see Manniu wearing a Japanese uniform, even going so far as to apologise for what the Pang family did to her. Wang Jin intervenes, praising Shengqian as a good man, before going on to explain that he has to take Wenxuan away because he has betrayed his country. Towards the end of the series Wang Jin describes Pang Shengqian as a great man of learning. The bourgeoisie is thus not condemned but rather held up as patriotic exemplars at a time of national strife, with Pang Shengqian representing the enduring greatness of the Chinese nation.

Similarly, the glories of Chinese civilization are held up through reference to traditional literary and philosophical texts. After Meng Zhenfei agrees to Manniu joining the Eighth Route Army, he tells her that she will serve as a secretary because she can write and is cultured. Her cultured background is apparent to Wang Jin, who responds to her request to keep a gun confiscated from the bandits by saying that he will teach her how to use the gun if she teaches him to read, adding that he has not read many books because he joined the army at a young age. In the coming episodes he is seen with a copy of The Dream of Red Chambers, the famous Qing dynasty novel, and astonishes He Cuiying by citing words from Xunzi, an early Chinese philosophical text, about persevering in the face of difficulty: on being asked how he acquired such knowledge he states that he has learned a lot from Manniu. After Cuiying’s death, when he calls on Manniu to recite a suitable poem she responds by chanting the elegiac ‘Guoshang’, from The Songs of the South, one of the earliest collections of Chinese poetry, as the soldiers march forward resolutely. [30] Apart from a brief glimpse of a poster of Mao Zedong on a wall during an army propaganda performance, there is no quotation from Maoist texts or exhortation to follow his example. Indeed, the heroes worthy of emulation come from an earlier age. In one of the early episodes, two peasants escape from the Japanese, who are on the point of slaughtering an entire village, through a tunnel that had been built some forty years previously by the Boxers, a group of indigenous rebels who sought to defend China against foreign invaders.

Linked to the whole question of the bourgeoisie is the thorny problem of the contribution made by the KMT to the defeat of the Japanese. Parks M. Coble has written of the changing ways in which the Anti-Japanese War has been remembered in China, noting that while during the Maoist period the element of victimisation was downplayed, more recently there has been a greater stress on Nationalism. At the same time the role played by the KMT during the war is examined and portrayed in more subtle ways, with greater acknowledgement of the contributions made by the Nationalists. [31] Thus, towards the end of the series it emerges that Lao Er, one of the bandits, has links with the KMT. When Houye, the senior figure among the three bandit prisoners, pays a visit in order to encourage them to join in the struggle against the Japanese, Lao Er is initially scornful, but subsequently has a change of heart and participates in the final battle. Some war-time figures, however, remain irredeemable: on the two occasions when Wang Jingwei, the leader of the Shanghai–based puppet government, is mentioned, he remains a symbol of all that is bad about Chinese collaboration with the Japanese.

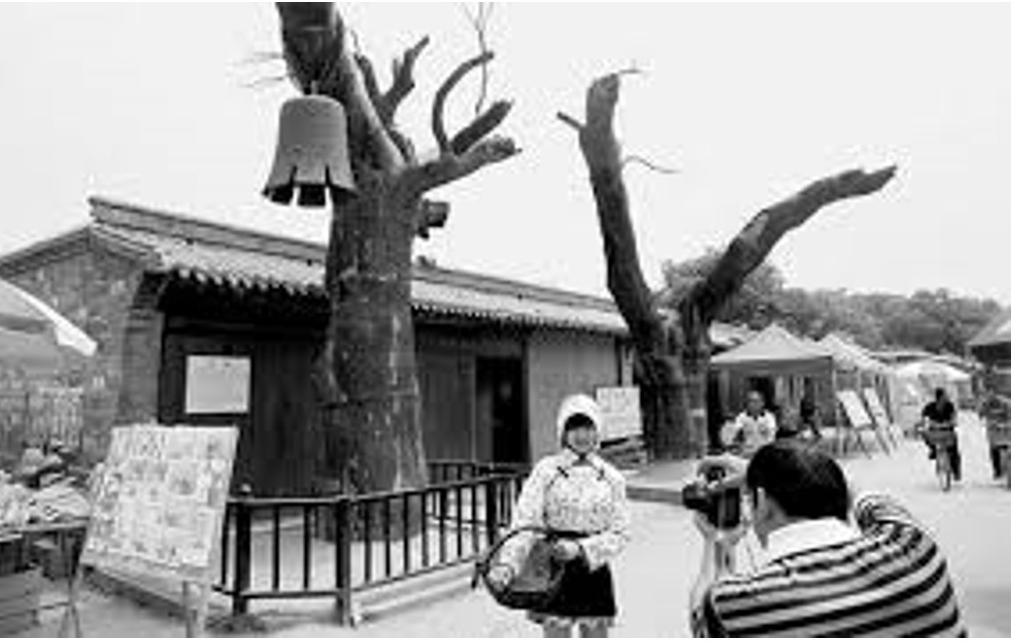

Changing Depictions of War

Chinese audiences are familiar with the tropes that so dominated the original era of the Red Classics. While much of the formal presentation of the TV series has moved on, there are some elements that do reappear. One particularly noteworthy use of iconography from the Maoist period of filmmaking occurs in an early episode when a bandit who had foolishly trusted the Japanese only to see them slaughter an entire village, walks past a bell that is just like the one that appears prominently in Tunnel Warfare (Ren Xudong, 1965): the bell has become an image that is become indelibly associated with the film. There are also several occasions when the cry of ‘Guizi laile’ (The Japs are Coming) heard regularly in Maoist era films and adopted by Jiang Wen as the title for Devils on the Doorstep, his 1999 film about the war, goes up at the sight of advancing Japanese soldiers.

|

|

The Village Bell

The use of the visual clichés for the depiction of Japanese soldiers so familiar from films of the Maoist period, however, has been ditched, with no sign of bad teeth, Hitleresque moustaches or round glasses, or other tropes such as the comic inability of the Japanese officers to speak the Chinese language. The unchanging message of the brutality of the Japanese and the saviour role of the CCP, however, remains present, albeit perhaps less prominently than in earlier periods of PRC history. There are some scenes of slaughter in which brave villagers are mown down by machine gun-toting Japanese soldiers, the first of which comes at the start of the fourth episode: the next, in episode fifteen, comes after a lengthy period with no action. There are, however, moments when a more nuanced vision is presented. In the opening minutes of the first episode, Wang Jin tells the soldiers under his command how he has heard that Japan is a beautiful country, full of cherry blossom. The guns of the advancing Japanese soldiers go off at that very moment, but the message is clear: it is not the ordinary Japanese people who are rotten, but those who are in charge. There is even room for the portrayal of a civilised Japanese man, although it is noteworthy that he is not part of the occupying army, but Wuwei Hezi’s father, who appears only briefly before being killed by an underground Chinese officer. The biggest Japanese trader in the region, he has collected many precious Chinese artefacts, and talks of his acquired taste for Chinese food and a recognition that the origins of the Japanese passion for tea drinking lie in links established between the two countries during the Tang dynasty.

Conclusion

The central themes of Guo Xiaochuan’s poem of loyalty and injustice are present in the poem, the film and the TV series. Over the course of the narrative, Wang Jin challenges the self-image of the bandits, who see themselves as brave and justified in their acts of rebellion, pointing out the self-serving nature of their exploits and convincing them of the value of serving the Chinese people through the Eighth Route Army. In turn, the bandits come to recognise the unfairness of Wang’s treatment. In the TV series, these themes become part of the overall message that war may be bad: this is heightened by sense that pre-communist Chinese society is also bad and it is only the CCP who can offer a bright future. Following Wang Jin’s ordeal in the river, Xiaolong, the grandson of his rescuer Qishu, says he knew immediately that Wang was an Eighth Route Army soldier, because he looks like his own father. Towards the end of the series when he visits Qishu, Wang Jin calmly tells him, on hearing that Xiaolong’s father has died, that from now on the Eighth Route Army will be his father and mother.

Wang Jin remains stoical throughout, even when physically attacked by his fellow prisoners or facing the threat of imminent execution. For the most part he responds calmly to all the baseless accusations thrown at him, though there are occasions when this is too much for him to bear, at which point he delivers a resoundingly patriotic homily, saying that his accusers should be using their strength to attack the real enemy, namely the Japanese. As the series progresses, these homilies become more frequent as the need for the correct message to be transmitted becomes more acute.

Even though the makers of the TV series were operating under hugely different circumstances than either Guo Xiaochuan or Zhang Junzhao and Zhang Yimou, and the characterisation is less crude and simplistic than in previous eras, the message is largely the same as before. Audiences may be more sophisticated but the long-standing ways of signposting good and bad characters remain largely in place. The slow buildup of incident is indicative of greater confidence on the part of the makers of the series in the level of understanding of cinematic narrative technique among the intended audience. Viewers have become more sophisticated so that the kind of exposition required in earlier times is no longer needed. The basic subject matter of the Anti-Japanese war is of course familiar and the TV series retains sufficient numbers of signifiers relating to the Anti-Japanese War while bringing in other aspects from contemporary TV series notably the love interest and the reduction of the importance of class conflict. In contrast to the fantasy world of Scarlet Rose: the Goddesses of Jinling, and the plethora of series which perpetuated the most egregious stereotypes, the TV series of The One and the Eight does, for the most part, revert to a grounding in reality.

It is tempting to ascribe feelings of personal injustice to the makers of the poem and the film. While staying at Yan’an, Guo Xiaochuan had witnessed the persecution, not just of the dissident Wang Shiwei, but of his own wife, Du Hui, while the Fifth Generation filmmakers had lived through the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution. Ni Zhen wrote, “The sad fate of the main character in One and Eight echoed their emotional and mental experiences and gave them an outlet for expression through art.” (158) In the years leading up to the broadcast of the TV series, the cultural environment changed again. The emergence, and great popularity, of the extended drama series, combined with the continued ramping up of the state propaganda machine, ensured that both the dark style of Guo’s poem and the combative techniques employed by Zhang Junzhao and Zhang Yimou were ditched for the more straightforward demands of the twentieth-first century TV series, complete with regular doses of patriotic pro-CCP outpourings.

In a summing up of productions broadcast in 2015, Xu Lanmei wrote of:

a big batch of TV drama series about revolutionary history resounding with patriotic Main Melodies which, by emphasising a correct historical viewpoint and value system in order to guide the creative process, have reversed the recent unhealthy trend of turning the War of Resistance into a game. There has also been a remarkable expansion in both the selection of material and the range of styles, leading to a genuine return to the use of historical incidents and the meticulous construction of historical atmosphere, forging the indomitable vitality of the people through the use of their bitter and glorious memories. [32]

Here is the reaction to the more fantastical elements found in the shenju series that had predominated in the period before the making of The One and the Eight. There may be none of the more excessive fights from other series but encounters between Eighth Route Army soldiers and the Japanese generally result in overwhelming victory for the Chinese.

What is unusual in the case of the TV series of “The One and the Eight” is that, unlike Red Sorghum, famous both for being the debut of Zhang Yimou and for its origins in stories written by 2012 Nobel laureate Mo Yan, or the revered children’s classic Little Soldier Zhang Ga, both Guo Xiaochuan’s poem and the 1983 film version were largely unknown: neither work has anything like as much amount of cultural capital as the Red Classics of earlier periods of Communist China. The makers of the TV series, through the appropriation of a text with a controversial backstory, put across an overtly nationalistic message, rendering the more challenging elements of the original story into an anodyne form through the process of Red Classicisation.

Notes:

[1] Marcia Landy, Cinematic uses of the past (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), pp. 16-17.

[2] Hong Zicheng, A history of contemporary Chinese literature translated by Michael M. Day. (Leiden: Brill, 2007), p. 86.

[3] Douwe Fokkema, Literary doctrine in China and Soviet influence, 1956-1960 (The Hague: Mouton, 1965), p. 244.

[4] Xing Xiaoqun “Yige he bage” yu Guo Xiaochuan de mingyun” (“The One and the Eight” and the fate of Guo Xiaochuan) in Guo Xiaochuan Yige he bage (The One and the Eight) (Beijing: Renmin Wenxue, 2015), p. 101.

[5] Xing, op. cit., pp. 98-101, 115.

[6] Guo Xiaohui, “Preface” in Guo Xiaochuan, Yige he bage, p. 2. The entire poem can be found here:

https://zhidao.baidu.com/question/178102182.html

[7] Hong Zicheng, A history of contemporary Chinese literature translated by Michael M. Day. (Leiden: Brill, 2007), p. 88.

[8] Xing, op. cit., p. 106.

[9] For discussion of the film, see Dai Jinhua, ‘Severed Bridge: the Art of the Sons’ Generation’ in Cinema and desire: feminist Marxism and cultural politics in the work of Dai Jinhua (eds.) Jing Wang and Tani E. Barlow London: Verso, 2002, pp. 13-48 and Ni Zhen, Memoirs from the Beijing Film Academy: The Genesis of China’s Fifth Generation. Translated by Chris Berry Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

[10] The Guangxi Film Studio youth unit was founded on 1 April 1983, only a few months before the completed version of The One and the Eight was sent off to the censors in Beijing. Paul Clark Reinventing China: a Generation and its Films (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2005), p. 79.

[11] See, for example, a recent essay by Andy Rodekohr which mentions Zhang Junzhao only in passing, ‘”Human Wave Tactics”: Zhang Yimou, Cinematic Ritual, and the Problems of Crowds’ in Li Jie and Zhang Enhua eds Red Legacies in China: Cultural Afterlives of the Communist Revolution (Harvard University Press, 2016), pp. 271-296. Zhang Junzhao died in June 2018. See “The Director Zhang Junzhao, pioneer of Fifth Generation filmmaking, has died: Zhang Yimou posts a message of condolence” at: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2184238

accessed 30/07/2018

[12] Zhang Yimou quoted in Rey Chow, Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography and Contemporary Chinese Cinema. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), pp. 153-4.

[13] Clark, op. cit., p. 81

[14] Ni Zhen, op. cit., p. 171.

[15] Clark, op. cit, p. 79.

[16] Zhong Dianfei, “Innovation in Social and cinematic ideas: A foreword given at the first Annual Meeting of the learned society of Chinese film criticism, Dalian 1984” in George S. Semsel, Chen Xihe, and Xia Hong eds Film in contemporary China: critical debates, 1979-1989 (London: Praeger, 1993), pp. 3-18.

[17] Rodekohr, op. cit., p. 283.

[18] Ni Zhen, op. cit., p. 173.

[19] Ying Zhu, ‘From Anticorruption to Officialdom: The Transformation of Chinese Dynasty TV Drama’ in Eileen Cheng-yin Chow and Carlos Rojas eds Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas. (eds.) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 343-358, Zhong Xueping Mainstream Culture Refocused: Television Drama, Society, and the Production of Meaning in Reform-Era China. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 2010 and Bai Ruoyun Staging Corruption: Chinese Television and Politics. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014.

[20] Gong Qian, ‘A Trip Down Memory Lane: Remaking and Rereading the Red Classics’ in Ying Zhu, Michael Keane, Bai Ruoyun eds. TV drama in China (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008): pp. 157-170. SARFT was subsequently renamed SAPPRFT (State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television of the People’s Republic of China), which in turn, in March 2018, became a part of the CCP’s Publicity Department.

See Lucas Niewenhuis “China Gears Up to Better Project Its Image Abroad Ñ And Control Its Message At Home” at https://supchina.com/2018/03/21/china-gears-better-project-image-abroad-control-message-home/ accessed 23/03/18

[21] Rosemary Roberts, ‘Reconfiguring Red: Class discourses in the new millennium TV adaptation of The Red Detachment of Women’ China Perspectives. 2015. 2: 25-31. The 1960 version was directed by Xie Jin, the 1970 Revolutionary Model Opera version by Pan Wenzhan and Fu Jie.

[22] Michael Berry, ‘Shooting the enemy’ in Divided Lenses: Screen Memories of War in East Asia. Michael Berry and Chiho Sawada eds (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2016), pp. 175-195.

[23] Mou Zaijiang, Kangzhanju weihe huobao yingping) ‘Why there has been an explosion of TV dramas about the Anti-Japanese War’ Tianya 2013 (4): 207-8.

[24] Li Guocong ‘KangRi shenju: shangcuo Huaqiao jiacuolang’ (Sacred series of the Anti-Japanese War: Getting on the wrong sedan chair, marrying the wrong man) Jiannan wenxue 2013.6: 201-202.

[25] The series was a co-production by Hebei Television Company, Beijing Television Art Center, and Shanghai Guangmutian Entertainment Company.

[26] The incident on the boat is one of the plot elements retained from Guo Xiaochuan’s poem. p. 29.

[27] The term used for Manniu is tongyangxi meaning a girl adopted into a family as a future daughter-in-law.

[28] Wang Xin “Zhang Tong zaisu Kangri Yingxiong ‘Yige he bage’ quanshi ‘xin’ Wang Jin” (Zhang Tong again plays an Anti-Japanese hero, creating a new Wang Jin from The One and the Eight): http://yule.sohu.com/20130911/n386380901.shtml accessed 26/07/18

[29] Geng, Song ‘Chinese Masculinities Revisited: Male Images in Contemporary Television Drama Serials’ Modern China, Vol. 36, No. 4 (July 2010): 404-434.

[30] For a translation of this poem by David Hawkes as “Hymn to the Fallen” see Ch’u Tz’?: the Songs of the South, an Ancient Chinese Anthology. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), p. 117.

[31] Parks M. Coble China’s war reporters: the legacy of resistance against Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2015.

[32] Xu Lanmei, ‘Xianshide duoyuan yinmgshe yyu lishidechuanqi zaixian 2015 nian Zhongguo dianshijuzuo gaigian’ (The varied shining of reality and the fantastical recreation of history: a survey of the creation of Chinese drama series in 2015) Dianshiju tiandi. 2016 (9): pp. 23-4.

Bibliography:

Ruoyun Bai, Staging Corruption: Chinese Television and Politics. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014

Michael Berry, “Shooting the enemy” in Divided Lenses: Screen Memories of War in East Asia. Michael Berry and Chiho Sawada (eds.). Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2016: pp. 175-195.

Yu Cheng, “Zhongguo dianying Diwudai Dainjiren, daoyan Zhang Junzhao qusi, Zhangyimou weibo daonian” (The Director Zhang Junzhao, pioneer of Fifth Generation filmmaking, has died: Zhang Yimou posts a message of condolence) at:

https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2184238

accessed 30/0-7/2018

Rey Chow, Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography and Contemporary Chinese Cinema. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

Ch’u Tz’u: the Songs of the South, an Ancient Chinese Anthology. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985.

Paul Clark, Reinventing China: a Generation and its Films. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2005.

Parks M. Coble, China’s war reporters: the legacy of resistance against Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago 2015.

Jinhua Dai, “Severed Bridge: the Art of the Sons’ Generation” in Cinema and desire: feminist Marxism and cultural politics in the work of Dai Jinhua (eds.) Jing Wang and Tani E. Barlow London: Verso, 2002.

Douwe Fokkema, Literary doctrine in China and Soviet influence, 1956-1960. The Hague: Mouton, 1965.

Qian Gong, ‘A Trip Down Memory Lane: Remaking and Rereading the Red Classics’ in Ying Zhu, Michael Keane, Bai Ruoyun, eds. TV drama in China. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008.

Xiaohui Guo, “Xiezai shuqian” (Preface) in Guo Xiaochuan Yige he bage, pp. 1-5

Xiaochuan Guo, Yige he bage (The One and the Eight). Beijing: Renmin Wenxue, 2015.

Zicheng Hong, A history of contemporary Chinese literature. translated by Michael M. Day. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

Marcia Landy, Cinematic uses of the past. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Guocong Li, ‘KangRi shenju: shangcuo Huaqiao jiacuolang’ (Sacred series of the Anti-Japanese War: Getting on the wrong sedan chair, marrying the wrong man) Jiannan wenxue 2013.6: 201-202.

Zaijiang Mou,”Kangzhanju weihe huobao yingping” (Why there has been an explosion of TV dramas about the Anti-Japanese War) Tianya 2013 (4): 207-8.

Lucas Niewenhuis, “China Gears Up To Better Project Its Image Abroad Ñ And Control Its Message At Home” at https://supchina.com/2018/03/21/china-gears-better-project-image-abroad-control-message-home/ accessed 23/03/18

Zhen Ni, Memoirs from the Beijing Film Academy: The Genesis of China’s Fifth Generation. Translated by Chris Berry Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

Rosemary Roberts, ‘Reconfiguring Red: Class discourses in the new millennium TV adaptation of The Red Detachment of Women’ China Perspectives. 2015. 2: pp. 25-31.

Andy Rodekohr, ‘”Human Wave Tactics”: Zhang Yimou, Cinematic Ritual, and the Problems of Crowds’ in Li Jie and Zhang Enhua eds Red Legacies in China: Cultural Afterlives of the Communist Revolution. Harvard University Press, 2016, pp. 271-296.

Geng Song, ‘Chinese Masculinities Revisited: Male Images in Contemporary Television Drama Serials’ Modern China, Vol. 36, No. 4 (July 2010): 404-434.

Xin Wang, “Zhang Tong zaisu Kangri Yingxiong ‘Yige he bage’ quanshi ‘xin’ Wang Jin” Zhang Tong again plays an Anti-Japanese hero, creating a new Wang Jin from The One and the Eight.

http://yule.sohu.com/20130911/n386380901.shtml accessed 26/07/18

Xiaoqun Xing, “Yige he bage” yu Guo Xiaochuan de mingyun” (“The One and the Eight” and the fate of Guo Xiaochuan) in Guo Xiaochuan Yige he bage (The One and the Eight) Beijing: Renmin Wenxue, 2015. pp. 92-115

Lanmei Xu , ‘Xianshide duoyuan yingshe yu lishidechuanqi zaixian 2015 nian Zhongguo dianshijuzuo gaigian’ (The varied shining of reality and the fantastical recreation of history: a survey of the creation of Chinese drama series in 2015) Dianshiju tiandi 2016 (9): pp. 23-4.

Zhu Ying, ‘From Anticorruption to Officialdom: The Transformation of Chinese Dynasty TV Drama’ in Eileen Cheng-yin Chow and Carlos Rojas eds Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas.(eds.)Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013: pp. 343-358

Dianfei Zhong, ‘Innovation in Social and cinematic ideas: A foreword given at the first Annual Meeting of the learned society of Chinese film criticism, Dalian 1984’ pp. 3-18 in George S. Semsel, Chen Xihe, and Xia Hong eds Film in contemporary China: critical debates, 1979-1989. London: Praeger, 1993.

Xueping Zhong, Mainstream Culture Refocused: Television Drama, Society, and the Production of Meaning in Reform-Era China. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 2010.