I. Schmuck

Elaine May made her film-directing debut in 1971 with A New Leaf, in which she also appeared. This was preceded by many years of stage work, most notably for the improvisational Compass Players in Chicago in the 1950s that would eventually lead to her collaborations, between 1957 and 1961, with Mike Nichols. But her roots in theatre may date back at least as far as her childhood on the Yiddish stage with her father (although details here are incomplete and contradictory). Soon after the breakup with Nichols, she acted in two films, Enter Laughing (Carl Reiner, 1967) and Luv (Clive Donner, 1967) and continued to write, act and direct for the stage.

This very sketchy outline of her career up to A New Leaf does not quite prepare us for the significance of her intervention in the cinema. As a Paramount title, A New Leaf stands out as the only film released by a major Hollywood studio during this period that was directed by a woman. May’s singularity would be repeated the following year with The Heartbreak Kid. Unusual among the four films she directed in that the screenplay was not hers but credited to Neil Simon and adapted from a story by Bruce Jay Friedman, The Heartbreak Kid would also be her one film that was a critical and financial success. Her next film, Mikey and Nicky, began shooting in 1973 but, due to a protracted post-production, was eventually released in 1976. She would not direct another film until 1987, Ishtar. By that time, a handful of women had made films in Hollywood. Ishtar, though, would be one of the most negatively received films of its era and taken to be a prime example of contemporary Hollywood profligacy. Her film work after this consisted of acting in a few films, extensive contributions as an un-credited ‘script doctor’ on various Hollywood films, and two credited screenplays directed by Nichols, The Birdcage (1996) and Primary Colors (1998). (She continues to write and act for the theatre.) Her most recent credit as a film director is for the PBS American Masters series, an hour-long episode devoted to Nichols, first shown in 2016. Whether this absence of directing opportunities for May was a type of punishment for the failure of Ishtar or whether it is the result of other (or additional) factors is a topic outside the scope of this essay.

Whatever May accomplished as a director and writer throughout her long career, her background in improvisation remains a touchstone in discussions of her work. None of her films were, in the strict sense, improvised. But improvisation within and beyond scripted material was part of the production process. To improvise as an artist is to create as one goes along, to continually discover new ways of conceiving of the work at hand. In the process, meaning and intent may shift, ambiguities and unresolved tensions may arise. I hope to be attentive to such matters here, even as I proceed with a certain amount of caution in tracing out improvisational notations. I am cautious for two reasons. The first is that I do not have access to the shooting scripts nor I am privy to production information beyond the most anecdotal. Therefore I cannot compare the differences between what is on the page and what is on the screen. The second is that our pre-conceived ideas as to what an improvised film might look or sound like are notoriously elusive, confusing production methods (which may involve certain improvisational techniques) with the final result, which may ultimately achieve a formalist rigour. Much of the myth surrounding Mikey and Nicky, for example, is that it was a film in which the lead actors extensively improvised. But Jonathan Rosenbaum has written that May’s script and the final film are remarkably close. Neil Simon has stated that May did not (due to contractual obligations) alter his script for The Heartbreak Kid but she directed the film in such a way that it felt improvised. (Shelley, p. 72) Simon’s claim is helpful in that it points towards the potentially constructed nature of an improvisational style. At the same time, two of the lead actors in The Heartbreak Kid, Charles Grodin and Cybill Shepherd, have testified to the extensive amount of improvisation that took place during the shoot. [1] Regardless of production specifics, the unresolved tensions in May’s films, arising through a combination of her ongoing preoccupations and her exploratory methods, have created a certain contentious reception history. Feminist responses to her films in the 1970s are one indication of this.

During the period when May directed her first three films second-wave feminist discourses on the cinema began to fully emerge. This work ranged from that of film critics such as Molly Haskell, Joan Mellen and Marjorie Rosen to academic inquiry produced by a range of scholars. For the first group of critics, May is at best the source of measured approval (Haskell) and at worst an embodiment of the most negative manifestations of a misogynist culture (Mellen, Rosen). But in the scholarly literature, May is barely acknowledged and, if so, negatively. One reason for the hostility or neglect is not difficult to fathom and is germane to this essay: the protagonists to all of the films that May directed are men (or, in the case of A New Leaf, the two lead roles are divided between a man and a woman) during a period when strong roles for women in Hollywood were dwindling. [2]

Central to many feminist discourses of the period (particularly in their academic incarnations) is the notion that women’s cinema (films made not only by women but implicitly for a new kind of female spectator) must be tied to women’s issues and to representations that resist the hegemonic. Agnès Varda’s One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977) is virtually made to order for such needs. In Varda’s film, communities of women bond, challenge traditional domestic functions, sing about experiences of childbirth and motherhood outside the control of church and state, and articulate a hope that men will eventually learn to become better human beings, accepting women as their equals. Such idealism is, to put it mildly, absent from May’s work. Rosen characterises May as an “Uncle Tom” to her gender and an artist “whose feminine sensibilities are demonstrably nil”. (Rosen, p. 363). Of The Heartbreak Kid, Mellen merely sees “emptiness”, the characters lacking “in redeeming grace”. But it should be noted that May’s films, for all their emphasis on male characters, do not participate in the contemporaneous New Hollywood fascination for the romanticised male anti-hero. If her protagonists are male, they are situated in a very specific manner, the “emptiness” on display, the lack of “redeeming grace” precisely the point.

In Ishtar, there is a sequence in which songwriter Lyle Rogers (Warren Beatty) is bemoaning his bad luck with women to his friend and fellow songwriter Chuck Clarke (Dustin Hoffman). “What a smuck I was”, says Rogers of his recently ended marriage. “Schmuck”, Clarke corrects him. “It’s not smuck. It’s shmuck”. “Smuck,” repeats an obtuse Rogers. Clarke again: “Schumck”. Rogers tries harder: “Ssssmuck”. Changing tactics, Clarke suggests that Rogers say “shh”. Rogers successfully completes this challenge. “Now say muck,” instructs Clarke. More success for Rogers. “Now say shh and muck together, real fast”, Clarke tells him. “Smuck”, Rogers proudly declares. The male protagonist in May is fundamentally a schmuck. For May, the Yiddish word schmuck implies its colloquial reference to a man who is a “loser”, someone who is such a schmuck he may not even be able to pronounce the word itself. This exchange in Ishtar might suggest a privileging of Jewish authenticity over Gentile repressiveness. But as well shall see, May is no less ruthless and discomfiting in her treatment of Jewish culture, including the men who represent this culture.

May’s male protagonists express basic needs: career success, material satisfaction, the perfect female mate, or even revenge against a perceived wrongdoing. But May views such needs with extreme detachment, one that is also manifested in the otherwise very different treatment of the women. In her history of the Compass theatre group, Janet Coleman has noted that during this early period of her career, May was writing plays in which women were often the targets of particularly cruel conduct by either their mothers or by other men. Another member of the group, Annette Hankin, states, ” ‘The heroines of [May’s] plays are always very vulnerable people who are eaten alive.'” (Coleman, p.112). Mother/daughter relations are of no particular concern to the four films May directed. But the cruelty of men towards women is central to all of these films except for Ishtar and in two of them (A New Leaf and The Heartbreak Kid) the cruelty is capable of producing an uneasy form of audience laughter.

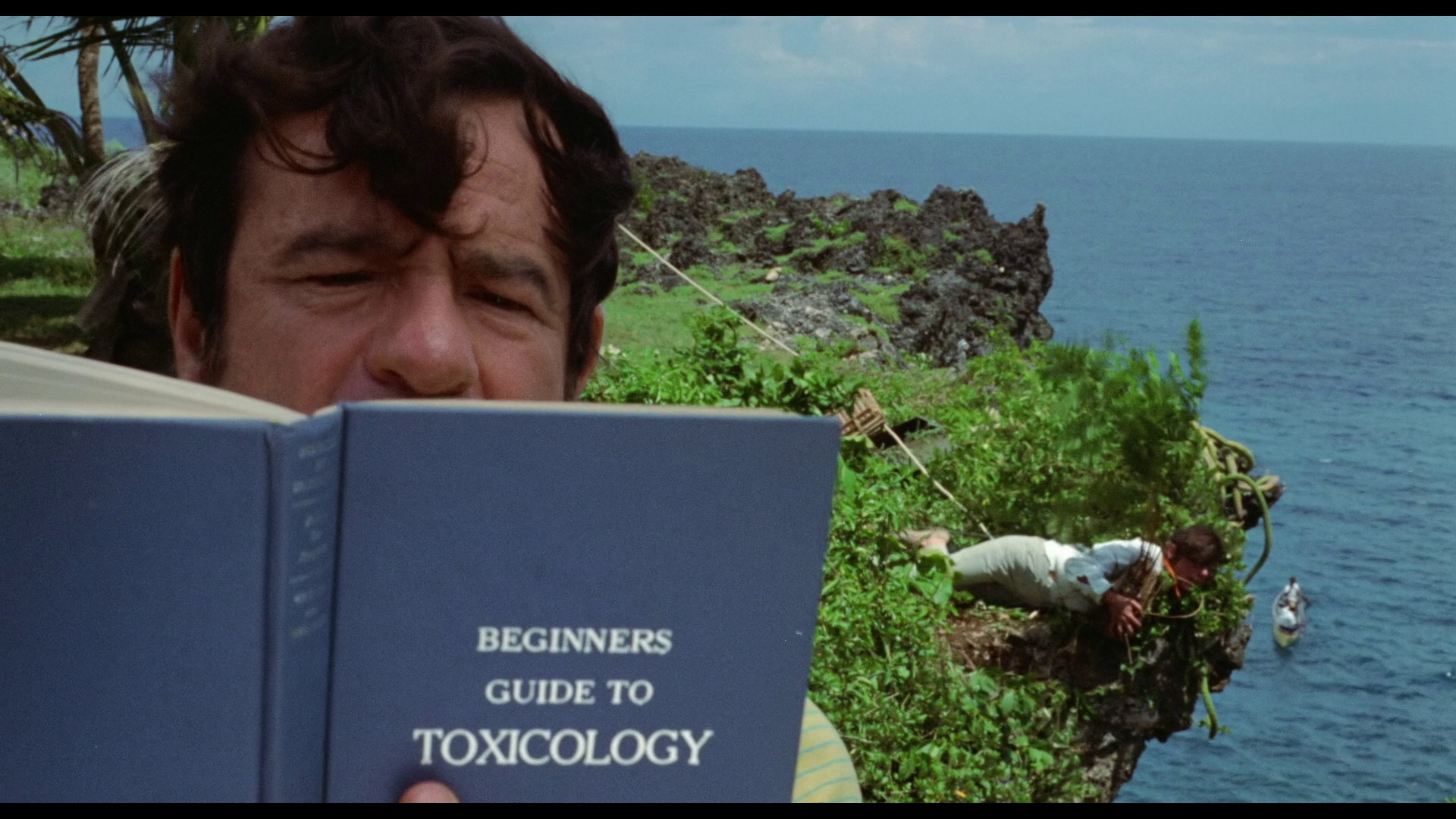

May’s aesthetic is abundantly comic. Situating that aesthetic within American cinema of the period in which she is making her early films, on the other hand, is a more difficult task. May’s films do not partake of the tendency towards parody, pastiche and the vaudeville and burlesque-like comedic sketch prevalent in the seventies films of Mel Brooks or Woody Allen. Her films also resist being fully part of the New Hollywood approach to humour. In Robert Altman, Hal Ashby, and Michael Ritchie, the comedy arises out of a gap between the satirical representation of decaying American institutions and the sometimes naïve, sometimes cynical protagonists, who are both enmeshed in these institutions and resist them. In May, if one resists at all, it is purely due to accident, fate, or sudden impulse, the protagonists more fully tied to the values of the rigid social and economic orders to which they belong. “In a country where every man is what he has,” declares the butler Harold (George Rose) in A New Leaf, “he who has very little is nobody very much”. And this need to resist being “nobody very much” makes of her protagonists particular kinds of comic figures. In Ishtar, as Clarke’s wife Carol (Carol Kane) leaves her failed and mediocre husband she tells him, “Your life is a joke”. When Clarke (who lived with his parents until he was thirty-two) attempts suicide by jumping off a ledge, Rogers coaxes him indoors by telling him, “It takes a lot of nerve to have nothing at your age. Don’t you understand that? Yeah, most guys would be ashamed, but you’ve got the guts to just say ‘the hell with it.’ You say that you’d rather have nothing than settle for less”. The laughter that May’s films provoke is frequently tied to observing this desperate desire to maintain a minimal form of dignity or to enjoy the smallest experience of happiness in the face of “nothing”. May’s humour is marked by its relentlessly dispassionate nature, evident in her treatment not only of individuals but also social forms, movements and institutions.

II. Forty… or Fifty… Years

To be dispassionate involves a process of literally and metaphorically stepping back or away from what one is observing. While feminist academic discourses of the seventies often addressed the issue of the male gaze in cinema, the camera relentless in its desire to control and contain its female objects, May’s films offers other possibilities. If a comic perspective is one that causes us to, in the words of Henri Bergson, “look upon life as a disinterested spectator” (1911/1999, p.10), May’s films make such a perspective dominant. As Henry (Walter Matthau) in A New Leaf proudly declares, “I can engage in any romantic activity with an urbanity borne of disinterest”. In May, the act of not simply looking but observing and witnessing recurs: the sustained look of disgust one character gives to another; the importance of figures within a group whose function is to silently observe; or the emphasis on characters watching the primary activities but without intervening. The act of looking in May remains, for the most part, tied to the male characters. But the characters’ status as schmucks places this “male gaze” within a decidedly problematic framework. Moreover, the visual and dramatic rhetoric of the films repeatedly situates the spectator’s own look at these often painful and embarrassing situations as another type of witnessing, the spectator helpless to do anything aside from laugh – and sometimes not even that.

The recurrence of such looks is tied to several factors. One is the function of time and, more specifically, a sense that time is in short supply. In The Heartbreak Kid, the pressure of time for sporting goods salesman Lenny Cantrow (Charles Grodin) is self-induced. On his honeymoon road trip from New York to Miami Beach, he quickly becomes nauseated by his young bride Lila (Jeannie Berlin) and once in Florida falls for another woman, abruptly terminating his marriage after five days. The doomed nature of his marriage is twofold. The first is that, like Lenny, Lila is Jewish, a “problem” not markedly apparent until the arrival of the blonde, Gentile Minnesota-native Kelly (Cybill Shepherd). Kelly’s first appearance is seen through Lenny’s eyes, in a low-angle shot as he is lying on the beach. “That’s my spot,” we hear her coyly say to him, looking down. The visibility of her face, though, is intermittent due to the brightness of the sun behind her. This presentation of Kelly provides the foundation for Lenny’s eminent obsession with her as a type of Gentile sun goddess, in contrast to the dark-haired and hairy-chested Lenny and the dark-haired Lila (who will soon burn in the sun).

Of the four films May directed, The Heartbreak Kid is the one in which Jewish representation is the most central. But this representation is neither on the order of a Mel Brooks, in which there is an alternation between farcical ethnic and racial parody and Jewish “in-jokes”; nor do we find, as in some of the seventies films of Paul Mazursky, the placing of a broad range of Jewish characters within a multi-racial, multi-ethnic world, one essentially realist in appearance but overflowing in comic and romantic possibilities. May is considerably more skeptical, about both the values of the Jewish culture from which Lenny emerges but also about the Gentile world to which he is drawn. That Gentile world is defined by the Minnesota winter that Lenny soon finds himself in as he chases Kelly there. This is a world where the temperature is always below zero and where the décor of the home Kelly shares with her parents is marked by its white, pale green, and beige sterility, all austere cleanliness and quiet. The master shot of the dinner sequence in this home, with Lenny as its awkward guest, is filmed with a short lens, exaggerating the distances between the four people seated at the table. The dark-haired Lenny becomes the incongruous point of contrast in this image, otherwise dominated by blonde and silver-haired Gentiles.

Through his ultimately successful pursuit of Kelly, Lenny will achieve social and economic mobility out of the Jewish middle-class world of Lila and into one of Protestant, Gentile wealth. The contrast between these worlds could not be clearer when Lila suddenly arrives on the beach, disrupting her husband’s reverie with her off-screen cry of “Lenny!” As he turns to look up at her standing on the promenade above him, she opens her robe to display her body in a two-piece bathing suit. But Lila is the opposite of a romantic vision. She is weighed down here with too many things (suit, robe, sun hat, towel, beach bag) as the agile Kelly looks back at Lenny, as though tempting him to cross over into her world. Even though Kelly is “real”, she is also a mirage. The status of that low-angle shot as she looks down at Lenny lying on the beach is ambiguous. We could easily read it as being Lenny’s point of view. And yet the shot precedes Lenny looking up at her. He is lying down, his eyes closed, and we see Kelly before he does. When he finally opens his eyes and looks up, it is the same shot as the preceding one. It is as though this image has summoned Lenny, tempting him, rather than Lenny actively generating it.

Lenny’s wedding to Lila is Jewish, complete with a reception dance to ‘Hava Nagila’. But with the marriage to Kelly, Lenny is now, as the minister phrases it in the film’s second and final wedding ceremony, “betwixt Christ and his church”, even overcoming the implied anti-Semitism and class snobbery of Kelly’s father. The film ends with Lenny alone at this reception, now disinterested in Kelly, and humming ‘(They Long to Be) Close to You’, a song that he and Lila danced to at their wedding and which they sang in the car en route to Miami Beach. Earlier at the second wedding reception, he tells some of the guests, “I would like to get back to origins”. Such a statement, when seen in tandem with the final seconds of the film of him humming a song linked with his previous marriage, should not necessarily imply that Lenny will return to his own “origins”. His declaration is, in fact, plagiarised from an editorial in a local newspaper and is a repetition of something Lenny has already uttered, during the dinner table conversation with Kelly and her parents when he was trying impress them with his philosophical breadth.

But Lila is also out of sync with Lenny because of her completely different experience of time. Haste defines Lenny. Lila, though, moves slowly. “Nobody waits any more”, Lenny tells Lila during an early sequence, when they are still dating and he wants to have sex. “I’m waiting”, she tells him. Lila is partly enacting the role of the “good Jewish girl” who waits until marriage to have sex. In neither Simon’s screenplay nor in the Friedman story on which that screenplay was based is Lila Jewish. May’s insistence on this point transforms The Heartbreak Kid into a different kind of project. Rosen describes Lila as a “leftover from the Yiddish stage or Ellis Island” (p. 364) and for Mellen she is a “Jewish vaudeville entertainer on Saturday night in the Catskills”. (p. 40). But one could equally see Lila’s Yiddish/Catskills evocation (if any) as an indication that her relationship to time causes her to lag slightly behind her own era. Once vows have been exchanged, though, the official sanctification of marriage causes her to become an ecstatic sexual participant while also overly eager in her need for sexual approval. Lila is, for her new husband, too little and too much, sexually voracious but infantile: she follows sexual intercourse with a Milky Way bar, becoming for Mellen, “a Jewish girl to whom a mouth stuffed with food is bliss”. (p. 40) Kelly, by contrast, has little apparent appetite and will slowly work over the same peanut or potato chip, appetite firmly under control. Lenny has, in essence, waited for nothing. Waiting, in fact, structures the film on several levels.

Simply in terms of the narrative situations, for example, once checked into their Miami Beach hotel room and with Lenny ready to go for a swim, Lila keeps him waiting as she endlessly brushes her hair. “Just two seconds”, she keeps telling him as she looks at herself in the mirror, “just two seconds”. A temporarily resigned Lenny sits on the edge of the bed and, in a wide shot, he stares at Lila as she fails to make progress. He finally suggests they meet downstairs, a plan to which she agrees, offering to come down in ten minutes. But it is within these ten minutes that everything changes: Lenny meets Kelly. Once at poolside, Lila herself loses track of time, stays in the sun too long and becomes extremely sunburned, forcing her to stay indoors, thus allowing for Lenny to pursue Kelly. For the remainder of the honeymoon, it is Lenny who will now keep Lila waiting as he, with increased desperation, has to convince her, long past the point of logic, to stay in her room. “The only thing that’s going to help you is time”, he says.

But waiting also extends to the form of the film itself. During their car trip, Lenny and Lila have a meal at the International House of Pancakes. As the sequence begins, we see a close shot of Lenny quickly ordering, a shot lasting three seconds, the camera tilting up from the menu to him. But Lila, beginning in a wide shot, keeps Lenny and the waitress waiting as she studies the menu, flipping through pages, and drawing out her decision-making process. Berlin prolongs Lila’s dialogue here so that the word and becomes “aaaaaannnnd….Let me see…I’ll have [long pause] double egg salad on toast. Aaaannnnd….” In the middle of this second and there is a cut to an over-the-shoulder two-shot of Lenny and the back of Lila’s head, as an embarrassed Lenny looks up at the waitress and Lila continues with her slow ordering: “….a, ummmmm, double chocolate shake”. It has taken her almost thirty seconds to order, the event spread out over two camera set-ups. After the ordering has finished, the film briefly cuts between a close-up of Lila and a close-up of Lenny, neither of them speaking. “You’re quiet this morning”, she finally says to him, breaking the awkward silence but also breaking the alternating close-ups as the camera moves farther back, into over-the-shoulder framings of the two of them. “I’m always quiet in the morning”, is his unconvincing response. “I never noticed that before”, she says. “There’s a lot of things you never noticed about me and a lot of things I never noticed about you”, he tells her. Grodin brings a slightly broken rhythm to that last line, as though he has run out of breath halfway through, and then emits an almost involuntary chuckle as he says, “a lot of things I never noticed about you”. If, as Simon claims, the film “feels” improvised even though it is (perhaps) not, then these hesitant or prolonged rhythms and awkward pauses and silences help to convey a sense of the scene being “discovered” as it unfolds. This approach stands in stark contrast to the many Simon comedies being turned out in Hollywood during this period, most of them adapted from his plays, in which the dialogue is directed and delivered in a very emphatic style, the pacing taken at a clip. [3] But Grodin’s idiosyncratic reading of the line arguably draws even more attention to the line than had he handled it in a more conventionally emphatic manner. To not notice things one should have noticed all along, to be blind to the obvious, is central to The Heartbreak Kid.

In the midst of this awkward conversation, Lila spots an elderly couple rising from a booth behind Lenny. “Lenny, look,” she tells him as we see the couple helping each other put their coats on. “You wanna see us in fifty years? That’s gonna be us, isn’t it, Lenny?” Throughout the early sections of the film, Lila keeps referring to the forty or fifty or even a hundred years that she anticipates spending with Lenny and she will often playfully extend the words “forrrtyy or fiffftyy….yyyyyyears” so that even these utterances have a temporal weight. Such a prospective time frame is the source of unending joy for Lila. But for Lenny it represents the corrosive, the inexorable. Before Lenny has turned to look around, we see in a wide shot, taken from behind Lila, the elderly couple rising, the wife helping her husband put his coat on. Just below them sits Lenny, in the booth, not yet seeing this. In one image, we have the dilemma Lenny imagines himself to be in. This elderly couple foreshadows what we will see once Lenny and Lila are in their hotel in Florida, surrounded by more elderly (and presumably Jewish) married couples, some wearing matching his-and-her outfits, as though this is what Lenny will turn into if he doesn’t move quickly.

Once her food arrives, Lila’s robust investment in eating becomes a source of revulsion for Lenny, as her clumsiness causes the egg salad to smear across her face. The over-the-shoulder shot alternations allow for Lenny to see the food on Lila’s face before the spectator does. Lila’s back is to the camera as he delivers the news of her accident. Grodin, though, does not utter the line in a straightforward manner. “You have a little, uh, [pause] a little…uh…uh,” he says pointing at her face. By the time he directly says “a little egg salad on your face” there is a cut to Lila, in close-up. Another pause as she wipes only part of it away. “Is it off?” “Yeah,” he says and slightly smiles in the reverse shot. For the spectator, the deliberate pacing seems designed to draw out the agony of the moment, one that also depends for its agony (as does the film as a whole) on dramatic irony. Even though the disgust that Lila engenders on the part of Lenny is fully visible to us, she remains oblivious. And yet the film creates no conventional pathos for Lila. Dispassionate humour and dramatic irony are rigorously maintained. If in the early plays of May, vulnerable women were “eaten alive” by cruel men, Lila’s innocent devouring of her food is the pre-condition for her being metaphorically devoured by a ruthlessly self-involved husband who, nevertheless, is another source of laughter.

Our responses to Lenny, then, are not immune from such irony either. The casual cruelty he exhibits in his indifference to the egg salad on Lila’s face intensifies throughout the honeymoon as she stays behind in her hotel room and her husband pursues another woman. Such irony can produce embarrassed laughter, as though we don’t quite know where to look. In his book on Mike Nichols, Kyle Stevens argues that none of the characters in the improvised comic routines of Nichols and May “can hear themselves, and so they cannot learn from the other”, a world in which there is “no consistent wise one, no fool”. For the spectator, this results in an uncertainty as to how we are to interpret the situations, so that we are often “questioning what must we do”. (Stevens, p. 50) Once May and Nichols become film directors, it is May who will more systematically pursue the implications of this approach. When Lenny, over a lobster dinner, breaks the news to Lila that he wishes to terminate the marriage he tells her, “It’s not the amount of time you spend with somebody it’s how the time was spent” while adding “I’ll never forget these three days”. The ludicrously inadequate nature of this attempt to soften the blow to his soon-to-be-ex-bride, all the while promising her a dessert of “yummy yum pecan pie,” allowing her to indulge in the voracious appetite that he also loathes (as though giving a favourite meal to a prisoner about to be executed) is a painfully funny example of this inability of May’s characters to hear (or see) themselves.

III. “I Don’t Like That Kind of Joke”

The need for these men to keep on the move, however, is not always a question of material and socio-ethnic ascension. “If I sit still and don’t move”, Nicky (John Cassavetes) says, “maybe they’ll forget about me. But then I’m scared of that too, because I think maybe if I sit there too long, maybe when I want to move, I won’t be able to move”. At the end of the film, and after being literally on the move in Philadelphia, Nicky is shot dead by the hit man Kinney (Ned Beatty) on the doorstep of the home of his best friend Mikey (Peter Falk) with whom Kinney has been collaborating all evening in an attempt by a resentful Mikey to set up his friend, who has stolen money from the mob. And central to this resentment has been humour.

When Nicky makes aggressive advances towards his mistress Nell (Carol Grace) she asks him to stop. “It’s a joke”, he reassures her. “I don’t like that kind of joke”, she responds. Mikey and Nicky is, among other things, about being the target of humour, of not appreciating the joke that is made at your expense. “Crying out loud gets you pointed and laughed at” are the lyrics (written by May) to one of the songs of Rogers and Clarke in Ishtar. And the humiliation Mikey has undergone over the years, his sense of inferiority at being “pointed and laughed at”, is partly due to Nicky’s jokes, which he has come to experience as accumulating betrayals. Humour in this film is at the crux of pain, disappointment, and cruelty in which death becomes the only way to put an end to the laughter.

In Mikey and Nicky, not only waiting but stasis and mistiming predominate. And whereas The Heartbreak Kid is a film of sunlight and blinding whiteness, Mikey and Nicky is a film of shadows, darkness. Unlike Lenny, Nicky is running from the light, from death: “That light’s gonna give me a headache.” All of the film takes place in a single night, aside from the murder of Nicky, which occurs at dawn. This morning light kills him, makes him visible. But his murder occurs in the morning because of consistent bungling on the part of Kinney and Nicky. “I look like a schmuck”, Kenney says to Mikey in relation to his ineptitude in tracking down Nicky. In the final sequence, as Kinney’s car hesitantly drives by Mikey’s house, on the lookout for Nicky, Mikey looks out his living room window and says “schmuck” under his breath at the sight of Kinney’s ineptitude manifesting itself once again. At the B&O Bar, one of several locations where Kinney is supposed to murder Nicky, the Andrews Sisters recording of “Beer Barrel Polka” with its lyrics, “The future’s full of promise/Tomorrow is another day” is played more than once; and the melody is heard again, in the final credits, the song’s optimism about the redemptive potential of time ironically mocked by the implications of the film as a whole. Late in the film, Nicky destroys Mikey’s watch. Nicky shrugs this off by telling Mikey that he’s had the watch long enough anyway. But joking about the watch (a gift from Mikey’s “solemn” father) only offends Mikey. “You think this is a joke? This is funny to you?” An important location for Mikey and Nicky is an all-night movie theatre playing a double feature whose titles signpost the issues at stake in terms of both the relentless pressure of time and the importance of incongruous laughter: Time of the Iron Hand and The Laughing Policeman.

At the beginning of the film, a hysterical Nicky tells Mikey, “I’m going die, I’m going to die”. But in a Catholic cemetery, where Nicky has impulsively gone to visit the grave of his mother, laughter predominates for Nicky. When Mikey, as a gesture of respect, recites the Kaddish over the grave, Nicky (to Mikey’s irritation) laughs: “My ma doesn’t mind me laughing, do you Ma?” Whether Nicky’s laughter trivialises genuine pain and loss or whether it is a legitimate response to them is an issue that the film does not resolve. A partial blindness for not only the protagonists but also the spectator is overriding and virtually literalised in the extreme low-key lighting of the cemetery. It is so dark that Nicky has trouble finding his mother’s grave and initially, as the blind camel will do in Ishtar, wanders about in confusion. But in Ishtar, the erratic movements of the camel take place under the glaring light of an African desert. Mimicked by Rogers and Clarke, it allows them to successfully avoid death at the hands of the CIA (in helicopters) attempting to assassinate the two men. In Mikey and Nicky, such “blind” movements ultimately lead to death.

Even such a fundamental element to comic form as repetition is off balance. Repetition here is not tied to denaturalising language and social behavior, as we find in A New Leaf, when Henry’s accountant exhausts every possibility for repeating the words “you have no money” to an obtuse Henry. Instead, repetition is embedded within a static world that has no regenerative sense of humour. Part of Mikey’s hostility towards Nicky mocking him is that Mikey often repeats himself but is unaware of this. Near the end of the film, Mikey asks his wife Annie (Rose Arrick), “Do I repeat myself when I talk?” She claims that she has never noticed. But we cannot be completely sure of this. An implied ethical question is raised by Nicky’s taunting: Is Mikey’s problem – and his own status as a schmuck – that he fundamentally has no sense of humour? “You don’t believe there’s anything after you die?” an incredulous Nicky asks Mikey while in the cemetery. But for Mikey, life after death is “that mishegoss I leave to the Catholics.” Unfortunately, Mikey’s Jewish skepticism about an afterlife does not translate into Jewish humour that could have served as a defensive gesture. Instead, the jokes of the Catholic Nicky have pre-empted this possibility. We never witness the various insults (real or imagined) that Mikey has experienced at Nicky’s hands, as these events precede the story time of the film. Instead, we must intuit things from the interactions between the protagonists over a single night.

Perhaps the most complex sequence in all of May’s films is the one in which Nicky seduces a resistant Nell in her apartment, as an embarrassed Mikey hides in a corner of the kitchen. In contrast to the comparatively conventional framing and découpage of the single-camera technique of The Heartbreak Kid, the multiple camera technique of Mikey and Nicky gives an impression of a seemingly infinite number of set-ups. [4] Even while certain traditional editing patterns are present, the extensive coverage makes it difficult (even on repeat viewings) to predict where the next cut will come and what kind of shot we will have. For all the varied angles here, though, May still cuts within a 180-degree space, with the wide master shots of the apartment creating a proscenium-like theatrical environment. However, these shots do not work to comfortably “ground” the spectator’s perception. Instead, in their physical distance from the dramatic action, combined with the use of low-key lighting (diegetically motivated when Nicky insists on lowering the lights) the effect is of enormous spatial and dramatic tension, arising not only out of unresolved issues between the two men but also in terms of the function of women within this dynamic.

“I love you”, Nicky says to Nell and then, in order to reassure her, “There’s no one else here”. This line is uttered at the same moment that there is a cut to Mikey, sitting in the kitchen smoking a cigarette, chair backed up against the wall, as though the line is for him even more than it is for Nell. A trope of the seventies Hollywood buddy film is two men sharing the same woman as an indication of their unconscious homosexual attraction for one another. After Nicky has succeeded in seducing Nell, he offers her to Mikey by saying, “I wanted to warm her up a little bit for you”. But such an allusion is not insisted on and this moment allows itself to be read in other ways. Mikey is, insofar as his relationship with Nicky is concerned, “no one” and he quickly assumes that Nicky has set up the entire situation in order to humiliate him yet again. “Don’t take any bullshit”, Nicky tells Mikey as he is leading Mikey towards Nell. “Put her down on the couch and tell her what to do”. Nicky hesitates but does not resist – and Nell ultimately, in the midst of the bungled seduction, bites Mikey on the lip. His response, however, is to slap her, a gesture that could be read as an indication that he is, ethically speaking and for all his hesitancy in this sequence, no better than Nicky.

And what is Nell in relation to all of this? She is variously understood to be – or described as – Nicky’s mistress, who keeps up with current political events and reads many books; and a mentally unbalanced “dumb hooker” (Nicky’s words) who merely enacts a charade of resistance to the advances of her male clients. The film’s refusal to offer a firm characterisation results in Mikey and Nicky being as systematic in avoiding pathos for Nell as The Heartbreak Kid is in avoiding pathos for Lila. Lila, though, is intended to provoke audience laughter (however uncomfortable) whereas Nell stops it cold, the ambiguities and ambivalences at the heart of May particularly exposed, as the camera alternates between being too close to her and, as though dispassionately observing her humiliation, too far away.

Is Mikey and Nicky a comedy, then? Chuck Stephens argues against those who would see the film’s dramatic texture as an exception within May’s body of work. Mikey and Nicky, he writes, is a film in which May’s humour is “biliously present throughout.” (Stephens, pp. 50-51). May herself, though, has said that it is not a comedy, even as she has acknowledged that, at a preview, audiences laughed throughout until the murder of Nicky, which was greeted with “stunned silence. And then boos, loud boos.” (May)

Perhaps another way of looking at the film would be to see it as pushing to the extreme the implications of dispassion from which so much of May’s comedy arises, so extreme that the film comes close to assuming a tragic dimension but enacted by two bumbling, comic characters. “You look at something one way”, May once said, “and it’s a disaster, you look at it another way and it’s humourous. It depends on how you tilt your head”. (Probst, p. 135) If Mikey and Nicky is a comedy, it is one in which a man slips on a banana peel but then dies from the fall, your possible laughter generated by the slip immediately cut short when you tilt your head and notice a dead schmuck lying in front of you.

Note: This essay was written a number of months prior to the publication of ReFocus: The Films of Elaine May (Edinburgh University Press, 2020), edited by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Dean Brandum. Any overlaps between my arguments here with those of any of the essays gathered in that volume are inadvertent. I review this book in Cineaste, Fall 2020, Vol. XLV, No. 4.

Notes:

[1] See Grodin, pp.190-193 and Shepherd, p.110.

[2] An exception to the male-centred tendency in May’s cinema during this period is her screenplay for Such Good Friends (Otto Preminger, 1971), done under the pseudonym Esther Dale. Such Good Friends belongs to a tendency among a small group of American films of the early seventies that focused on the lives of bourgeois New York housewives, a group that would include Diary of a Mad Housewife (Frank Perry,1970) and Up the Sandbox (Irvin Kershner,1972), adapted from novels written by Jewish women, respectively Sue Kaufman and Anne Richardson Roiphe. Such Good Friends (adapted from a novel by Lois Gould) is fully representative of May’s work. But I have chosen not to address the film here, partly because she did not direct it but also because, in its focus on a female protagonist, it raises issues that would take the essay too far afield from its more immediate concerns.

[3] May appeared in one of these, California Suite (Herbert Ross, 1978), opposite Matthau.

[4] Much has been made of the connections between Mikey and Nicky and the films directed by Cassavetes, not only due to the casting of the two leads (Falk was a Cassavetes regular) but also in the film’s improvisational atmosphere. But one need look no further than Cassavetes’ Husbands (1970), also starring Falk and Cassavetes, to see how different May’s film is from those of Cassavetes. In Husbands, as in much of Cassavetes, there is an agonised search for the authentic, partly enacted within the fiction (with the titular characters discussing the importance of truth and lies, of feeling things “from the heart” and enacting this through performance rituals, such as pub singing). But the search for the authentic is also apparent through the visual style. Cassavetes’ multiple camera shooting gives the effect of an overflowing frame that can barely contain all that it needs to show; whereas May’s use of it (both films were shot by Victor Kemper) has to do with capturing something from within a centripetal space, as though burrowing into an environment. Husbands creates a fully organic world, with wives, families, and normalised social rituals. By contrast, Mikey and Nicky is a film in which the families and close childhood friends of the two men are all dead. As in Mikey and Nicky, a funeral sequence is crucial. But Cassavetes stages it in bright sunlight, his characters actively resisting death. “A Comedy About Life Death and Freedom” is the subtitle for Husbands. If such a subtitle were ever to be used in a May film, the word freedom would undoubtedly be lopped off and, along with it, the tortured romantic underpinnings of so much of Cassavetes.

Bibliography:

Henri Bergson, Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic. Trans. Cloudesley Brereton and Fred Rothwell. Los Angeles: Green Integer, 1999. Originally published 1911.

Janet Coleman, The Compass: The Improvisational Theater That Revolutionized American Comedy. The University of Chicago Press, 1990.

“Elaine May in Conversation with Mike Nichols.” 2006. Film Comment, July/August 2006. Available at https://www.filmcomment.com/article/elaine-may-in-conversation-with-mike-nichols/

Charles Grodin, It Would Be So Nice If You Weren’t Here: My Journey Through Show Business. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1989.

Joan Mellen, Women and Their Sexuality in the New Film. New York: Dell Publishing, 1974.

Leonard Probst, Off Camera: Leveling About Themselves. New York: Stein and Day, 1975.

Marjorie Rosen, Popcorn Venus: Women, Movies and the American Dream. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Inc., 1973.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, “The Mysterious Elaine May: Hiding in Plain Sight.” Available at: https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/

Peter Shelley, Neil Simon on Screen: Adaptations and Original Scripts for Film and Television. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2015.

Cybill Shepherd with Aimee Lee Ball, Cybill Disobedience: How I Survived Beauty Pageants, Elvis, Sex, Bruce Willis, Lies, Marriage, Motherhood, Hollywood and the Irrepressible Urge to Say What I Think. New York: Harper Collins, 2000.

Chuck Stephens, “Chronicle of a Disappearance.” Film Comment, March/April 2006, pp. 46-53.

Kyle Stevens, Mike Nichols: Sex, Language, and the Reinvention of Psychological Realism. Oxford University Press, 2015.