Introduction

Not five minutes into to Baby Face (Alfred E. Green, 1933), the most notorious and scandalous picture produced by Warner Bros in the pre-Code era, Lily Powers (Barbara Stanwyck) is posed at the window of her father’s speakeasy, the camera capturing her watering the plants through the open window. Soon a man appears – he’s clearly a drunken lout – but all we see is his glistening, muscular torso, as his face is entirely blocked by the window frame. This is a key moment in the history of cinema, and indeed the culture of gender and bodily representations: that a man is seen as nothing beyond his body.

Minutes earlier, Baby Face opens on a bountiful display of men, rough and dirty after a day’s work and thirsty for a drink. The only women in sight are Lily, wearing a plain dress, and her friend and maid Chico (Theresa Harris); both are bored and uninterested in their lives. Apparently, none of the men have any concept of romance and no cares for anybody but themselves. As Lily says, “They’re pretty mangy.” A little later, a man clearly coded as vulgar walks into the bar and focuses on Lily. His gaze starts at her feet and makes his way up to her face, and on the way pauses very noticeably not at her bosom, but in her lap. The blatant and undoubtedly violent sexual predatoriness implied by this gaze is one that, in the coming days of the Production Code, would be replaced by something of a more innocuous – but unmistakeably sexual – nature. In pre-Code cinema such as this film, the implication is straightforward.

Male body on display at a Pennsylvania speakeasy in Baby Face.

In 1930 the association of Motion Picture Producers and Distributers of America [MPPDA], at the time headed by Will Hays, proposed that Hollywood’s creative output be regulated by a code dictated by the Studio Relations Committee [SRC], purportedly with every American’s best interests in mind. The interests in question, however, were primarily those of the Catholic right and conservative militants, fearful of libertarianism, libertines and independent women, and the female in any form was particularly subject to censorship. From 1930 when the Code was informally proposed until mid-1934 when it was administered with great vehemence, Hollywood produced cinema as it had never been seen before, and has never been seen since. In The Wages of Sin: Censorship and the Fallen Woman Film, 1928-1942, Lea Jacobs writes that although “all the variants of the fallen woman film were eventually subject to censorship by the MPPDA, the version in which she came to a less than unhappy end made the representation of illicit sexuality especially problematic.” [1] The fallen woman film, as Jacobs terms it, belongs to a genre characterised by any one of the following facets: the vamp, the gold-digger supplemented by class rise, and the maternal melodrama. In 2018, even with access to archives and decades of academic analysis on the 1930s, the difficulty of defining the pre-Code body is apparent in that the films were subject to censorship throughout pre-production, in script development, and even after a complete film was presented. What was proposed and what was eventually seen on screen were often separated by a gulf of censored material, and even with the many decades’ worth of historic correspondence uncovered since, it is often difficult to determine the extent.

The pre-Code body is an interesting figure in the history not only of cinema, but of society and culture, because prior to the enforcement of censorship restrictions it was often taken far past the limits of transgression. As Jacobs writes, “Before 1934, negotiations between producers and industry censors involved discrete and localized elements of the text”, [2] and censors involved groups of scriptwriters, directors and producers in a conversation of negotiation regarding their films. This climate of negotiation made it easier for those in Hollywood to use censorship to their benefit, or at least to alter their own material in a way that circumvented the proverbial letter of the law without compromising their content. Loosely guided by Hays’ moral fortitude, censors were fairly didactic in their attempts to control Hollywood’s output, their suggestions could be appealed by producers and their opinions rejected by the Hollywood Jury, a board comprised of other producers. In many cases, in support of their own kind, the Jury favoured producers and final edits were left up to the studios producers in respect of artistic honesty. Censorship of both the male and female body was a key facet of the 1930 Code and its presentation often the target of the censors. Without any officiated support, and with Hollywood creating a wealth of “risqué” motion pictures, the body in pre-Code cinema is important to the presentation, and the perception, of gender and sexuality on the whole.

In April of 1934, perhaps in response to the overwhelmingly brash presentation of gender and sexuality combined with the untenable position of industry censors, members of the Catholic Legion of Decency threatened to boycott Hollywood cinema. At this overwhelming and unrelenting opposition to the freedom of content in cinema, the Hollywood Jury was disbanded and replaced by the more direct, and more difficult to evade, Production Code Administration [PCA], whose appointed head was Joseph Breen. Under his tutelage Hollywood was subject to the conceits of humourless critical orthodoxy; his overactive moral code had an adverse effect on almost every part of life and society in the cinema, not least in regards to representations of gender. The essence of his destructive reign over the liberal side of Hollywood can be summed up with this comment from Mick LaSalle, direct in his criticism of the PCA’s dour piousness: “To a large degree, the Code came in to prevent women from having fun.” [3]

Women Before Men in Baby Face

Before this occurred, the architects whose regulations failed in the pre-Code era tried to prevent women from having fun, and for the large part failed. The Wages of Sin includes an extensive discussion on Baby Face, with Jacobs taking particular interest in the film as what she would call a “limit case”, or a film hindered by a heavy flux of interference and resistance from both sides of the censorship battle. Also, as is well known, it was a film that proved particularly offensive to the Legion of Decency and was an identifiable catalyst in the proper enforcement of the 1934 Production Code. Writing in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the only version that Jacobs had access to was the studio version, censored quite dramatically for its 1934 release, and could surmise its alterations only from drafts of the script and archival correspondence between studio staff, industry censors, and religious conservatives. The original version of the film – unseen for over 70 years – was discovered in 2004 by Michael Mashon, a curator at the Library of Congress, and is now an essential and invaluable piece of history that elucidates the specifics of the prudish apprehension of the censors. The story of Baby Face stemmed from an idea by Darryl Zanuck (under one of his many pseudonyms), likely influenced by Red Headed Woman. [4] Zanuck was an irreplaceable talent at the Warner studio and a top-notch producer, and like any other studio producer, of course, was not welcoming of any interference. Unfortunately for Warner Bros, a problem that censors frequently identified with scripts or original release films was that “adultery is made attractive” [5] and in Baby Face, Lily always gets what she wants and she has a hell of a good time getting it. As her glamorous clothing and lifestyle increases, adultery is made very attractive. By the time of its American release on July 1, 1933, Baby Face had had many changes imposed on its representations of sexual freedom, female agency and ambition, and masculine aggression, more pronounced in the restored print but, when seen with a knowing eye, still fairly candid. The development of Baby Face, then, is something of a microcosmic representation of the larger Hollywood narrative of the pre-Code era, and provides a key example of a film with which to analyse the presence of the pre-Code body.

The rediscovered cut of the unreleased Baby Face is, as should be expected, much more sassy than its already audacious 1933 counterpart that was subject to heavy revisions. Both versions prove transgressive of moralistic codes of conduct and accepted notions of gendered behaviour. Thomas Doherty offers this interpretation of films like Baby Face:

The bad girl film holds to a gendered code of human behaviour: a determined female sexual predator can break down the resistance of any male no matter how outwardly moral his exterior. [6]

A study of several films suggest that this was not the case across the board, and indicates that there was a more discerning analysis of behaviour of the female and treatment of the body in Hollywood at the time. The original script of Baby Face has a rare gem of a character in the form of the wise father figure, Adolf (Alphonse Ethier), a humble cobbler who eagerly offers advice that is sinfully unorthodox – his scenes were unfortunately post-dubbed to appear rather anodyne. Adolf earnestly guides Lily to go to great lengths, any lengths, for personal success. “Use men to get the things you want,” he advises, via Nietzschean philosophy. She doubts herself at first, replying sarcastically, “I’m a ball of fire, I am” (but later given a delicious response by Howard Hawks and scriptwriter Billy Wilder when Stanwyck was cast as a gangster’s lady of burlesque in the 1941 film Ball of Fire). Despite the sinister undertones of exploitation (which, in such society, worked in favour of men anyway), this is pretty great advice. Lily realises her potential and follows it, starting with seducing a railroad worker to get herself and Chico to New York free of charge. But this is not a simple transaction underlined by the concept of sexual bribery, whereby a woman could only move upwards in society by exploiting her body. It is a step in a complex philosophical way of life touted by Nietzsche. As Lily reads from a volume sent to her by Adolf, the camera pauses on this page: “Face life as you find it – defiantly and unafraid. Waste no energy yearning for the moon. Crush out all sentiment.” For the most part, Lily does this, and succeeds in confirming that the position of men is one of secondary worth to women. Later in the film when Lily has already seduced a number of men, she schemes to have her affair with Mr. Stevens (Donald Cook) discovered by his wife. She is left alone in his office and perches triumphantly on his desk, and tightly crossing one knee across the other, she lights a cigarette. In a subsequent scene, she enacts the role of victim in front of the bank’s Vice President Mr. Carter and takes the same position, exposing her knees as she trembles on his couch. With this repetition of her positioning Lily presents herself openly to men, but it continues to be the men who overtly commit the wrongs; both the lower- and higher-class man is clearly signified as responsible for the breakdown of social propriety and organisation. Lily merely takes her place in that structure.

“Anything for glamour”: the enchantment of the female body

Baby Face differs from another notorious film about a woman on top, Red Headed Woman (Jack Conway, 1932). Where Lily Powers showed career and personal ambition in her sexual drive, Lil Andrews (Jean Harlow) only wants money and a man. Conceived as a gold-digging homewrecker, she is interested only in wealth and not in working to get it. Lil is salacious and she takes her sex appeal for granted, spurning responsibility and social effort. On the other hand, Lily always works hard to get to where she wants to be. And although she is definitively ruthless in getting there, she does put time and toil into her (albeit brief) relationships – she has been guided by a strong work ethic, after all. While we see that men do, at the beginning of the film at least, eye Stanwyck’s body, the direction of the cinematic scopophilia promptly changes direction, and Lily victimises men as the target of her gaze. Towards the end of the film, a scene opens in Lily’s lavish apartment, the camera tracking out from a record player to gradually reveal Lily, her body supine as she drinks champagne. This shot differs from earlier in the film when she was the target of a male gaze. Here, there are no men around and the camera is in service of Lily’s glamour, revealing not her body but her personal achievements.

Jean Harlow gets a leg up in Red Headed Woman.

Of course, Red Headed Woman is primarily a comedy, compared to Baby Face’s sincerity as a melodrama. Therefore, while Conway might have had no qualms framing the feminine body for laughs, Green had a more serious issue at hand; the basic operations of relations in society. MGM was in the business of grand-scale gloss in the pursuit of entertainment; Warner Bros was run by Democrat Jack Warner, and its films generally had a social conscience. As a melodrama, Baby Face was necessarily political, and its treatment of the tension between the male and female body culturally relevant. Jacobs discusses the climate of negotiations between the studios, producers, and censors, noting that “industry censors had hopes that the comedy itself would offset the potentially offensive aspects of the characterization of the gold digger”, and that the frivolous nature of the comedic mood allowed for more room to present material that might otherwise be considered indecent. [7] This reasoning might account for Jacobs interpreting the story of the gold-digger to be fairly comedic whereas the representational premise of the Depression and economic troubles was presented straightforwardly. Lily’s story is not comedic, even though she is clearly having a good time; rather, men that she seduces are often represented as dull idiots for allowing themselves to be duped by her. In response to Red Headed Woman, Jason Joy (who at the time was director of the SRC) wrote that its content was entirely contrary to the Code yet it was so farcical that he was “convinced that it was not contrary to the Code and would not (if properly advertised) cause [the SRC] any undue concern.” [8] Joy’s statement, however, seems in opposition to the text of the 1930 Code, which stipulated that adultery, seduction and “impure love” were not to be presented as comedy.

Given its framework of production, and as a melodrama, Baby Face was a serious comment on the nature of modern society and a powerful piece in the war against paternalistic conservatism. While many of its contemporary films were merely concerned with women who used their sexuality because they could, it is made very apparent that Lily’s body has already been exploited by men. With this in mind, the promiscuous sexuality that she employs cannot really be opposed as other men have already ‘spoiled’ her. Jacobs suggests that, like other films of the cycle, “class rise motivates the gold digger’s aggressivity and makes her a threatening figure.” [9] While this is undoubtedly the case for figures like Lil in Red Headed Woman, Lily’s incentive never stemmed only from rapaciousness but from a desire to avenge years of use and abuse by vulgar men. Lily never uses her sexuality just for the sake of it but always directs it towards getting a better life, which ties her identity as a woman inextricably to her position in society. Her incentive, essentially, is to, through personal effort, re-establish her individuality and humanity. “Have you had any experience?” asks her potential employer, when she first enters the bank looking for work. “Plenty,” replies Lily, drily, who was prostituted out by her own father from the age of 14. Lily understands the bitter power in this, and her body becomes her curriculum vitae, so to speak.

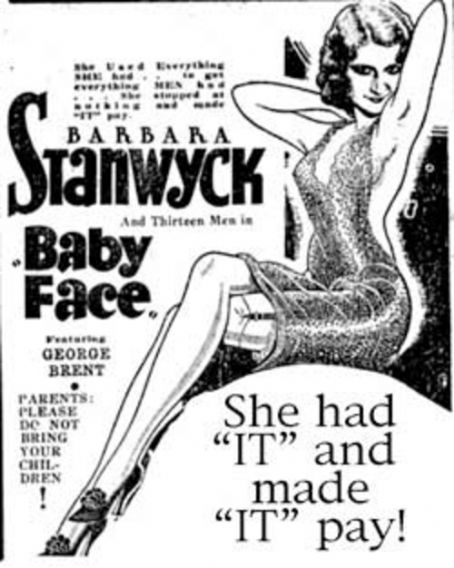

Promotional material for Baby Face.

Her self-motivating sexual prowess begins surreptitiously and then, once uncovered, becomes expertly powerful. Advertisements for the film boasted, “Barbara Stanwyck and thirteen men,” making the men absolutely the objectified sex in Baby Face. As an extension of this, it almost seems like a warning to men: despite how you’ve tried to frame them, women have depth beyond their looks. By using this sensationalism and star power to advertise the film, Warner Bros eclipsed much of the work imposed on the script and the final release print, by explicitly linking Stanwyck (note, her star persona, not her character) with many men. This single sentence reestablished the links between Baby Face and her seductees that were effectively separated in revisions of the script.

Jacobs provides insights into the alterations between the original print of Baby Face and the official release version. Many of the changes were extensions of the narrative ellipses that elided any explicit representation of sex. For example, there is a scene in the original print of the film where Lily Powers seduces a rail worker to escape punishment for stealing a ride to New York. A request from James Wingate, who became director at the helm of the SRC after Joy’s resignation, to remove a shot of the man’s glove falling from his hand proved too much of a compromise to the scene. Instead, the entire sequence was removed, and the train journey condensed to a single shot of a locomotive and Stanwyck, stowed away with Chico in a darkened carriage, announcing, “Next station is New York.” [10] When Lily first gets to the big city and gets a leg up the first rung of the bank’s ladder, she tempts an office assistant into his boss’s office in order to secure a job. In the original print, the camera sees her open the door and walk through, and stays until he has followed her into the room and closed the door, ‘Private’ stamped across the glass. In the print theatrically released in 1933, this scene was drastically truncated and audiences would only have seen his eyes follow her into the room; the scene cut with him still seated at his desk. The implications are still there, but audiences would have had to think a little harder in order to picture the couple together behind closed doors.

Essentially, the changes to Baby Face applied by the censors were fairly localised in that they changed the moral undertones of Lily’s rise to success to make her seem more remorseful and less driven. While the censors managed to eliminate quite a number of explicit moments, Jacobs concludes that such revisions “did not substantively transform the logic of the progression of the narrative.” [11] What these changes suggest is that Lily’s exertions of promiscuousness are not justified because she is abiding by a fairly indecorous ambition, so she must be punished in the final reel. The censors removed from the final print the shot of the politician handing Lily’s father some money, obliterating any textual suggestion that Lily was actually prostituted out by her father; it seems that this point of censorship in particular wanted to somehow absolve the degenerate patriarchy from responsibility, and emphasise Lily’s stumbling onto the “wrong” path. Yet even without this particular inclusion in the moral plot, the dialogue and the advertising informed the spectator of these specifics. Doherty cites a tagline (a modification of an equally explicit line that Lily shouts at her father) as something used in contemporaneous advertisements: “I don’t want to keep on living like a dumb animal! So I’m getting out. My father called me a tramp. And who is to blame? A swell start he gave me. Ever since I was 14 men have been trying to paw me!” [12] No mistaking this: Lily’s virtue was already taken by her father and his cronies, and she spends the film taking it back. To an intelligent audience (and by all accounts, many cinemagoers of an earlier time would have been no less knowing and alert than those of today), such censorship would have done little to the overall text.

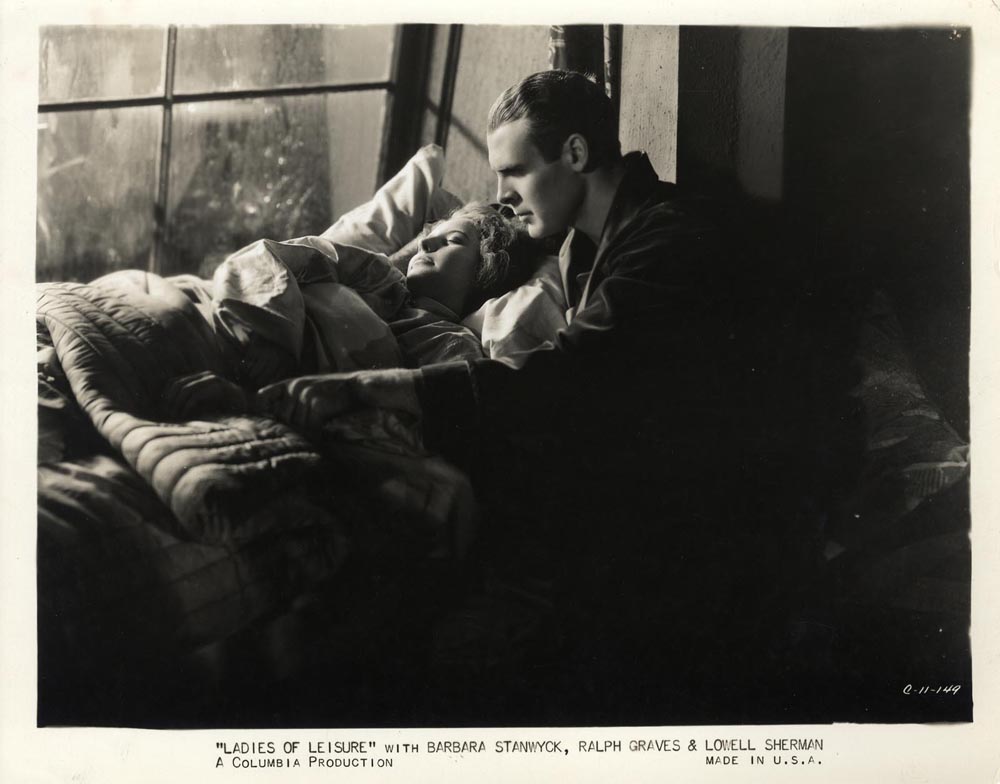

In an even earlier film starring Jean Harlow, Platinum Blonde (Frank Capra, 1931), Harlow is the most objectified, sexualised character in the film, and is made so in a way that was, and remained, normalised in Hollywood for a long time. As the blonde of the title, Anne Schuyler, she is the only woman to whose sexuality our gaze is explicitly directed. The other primary female character in the film, Gallagher (Loretta Young), is treated by Stew Smith (Robert Williams) as only a friend, “one of the boys,” whose femininity is wholly stripped from her where he is concerned. In a conversation with Gallagher when he is discussing Anne’s sexual predatoriness, he is dismissive when she starts, as he says, “talking like a woman.” Later on he explains that, among he and his colleagues, “We never look at Gallagher as a girl.” Smith dissociates Gallagher from Anne because she is never consciously a sexual option to him; in the same capacity, Anne is targeted as having no qualities aside from her femininity and sexuality. Enforcing the point, none of the men are seen as sexual in the slightest, and even when Anne and Smith are kissing behind the fountain glass wall it is her body that remains the focus point in the frame. Finally, when Smith realises that Anne is not, as he sees it, wife material and divorces her for Gallagher, the dominant form of family values is reinforced, with extroverted sexuality unaccepted in marriage. The film reasserts the heteronormative lifestyle as desirable, and by completely reneging on unity of class values, does little to evaluate or resolve sexual or gender tensions. It is much less impressive and penetrative than some of Capra’s other films made at Columbia, such as Ladies of Leisure (1930), It Happened One Night (1934) and The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933).

In spite of the fairly lacklustre Platinum Blonde, Jean Harlow does get to transgress the normative definitions beyond expected limits in Red Headed Woman (despite its status as a comedy) which may be a result of MGM’s relative freedom amongst the studios. The differences in Baby Face and Red Headed Woman, which are fairly similar in explicitness of vice, can be traced the further we go into the texts. Jean Harlow shows off her skin, as attention is immediately drawn to the more sensual parts of her body from the opening shot framing Harlow’s semi-nude bodice. It then cuts to her in the final touches of Harlow getting dressed, asking a saleswoman if her dress is see-through and, when the answer is affirmative (we can see the outline of her legs through fabric), deciding she will keep it on. Cut to her legs, and a close up of her gartered thigh held for a remarkable seven seconds. At this point, and throughout the film, the camera quite carefully leads the spectator’s eyes to Harlow’s undressed presence in offscreen space. It was common practice for films of the pre- and Production Code era to lead the mind’s eye into offscreen space, as cinematographer Harold Rosson does when Lil and Sally (Una Merkel) change outfits – the camera cleverly slides from one to the other, leaving the most revealing moments to the imagination – almost, but not quite, “like an uncensored movie”.

There is nothing like this in Baby Face – Barbara Stanwyck remains dressed. Although we know her to be more or less unscrupulous, she remains without doubt a strong woman, in control, and always very well (and fully) clothed. In a publicity run for Baby Face in 1933, Stanwyck said, “Everyone else has glamour but me so I played in Baby Face. Anything for glamour.” [13] With Stanwyck dressed elegantly (in Orry-Kelly, no less), it is the male body that becomes the object of the gaze, as in that first torso seen through an open window. Again, such differences are intrinsically tied to its status as a melodrama, and it is worth noting that even though Lily does lose her material wealth at the end of Baby Face, she is never embarrassed. Her stoicism allows her to survive and, in the end, she does get what she wants in that she loves her husband, and he survives. In Red Headed Woman there is little value put on the realism of the scenario, with Lil ending up in Paris, a coveted socialite with, it seems, no troubles in the world. While there is no problem with her having escaped the country and her ordeal unscathed, there is little explanation of how she ended up in Paris; she just ends up there. In The Wages of Sin, Jacobs reflects on the overtones of glamour in the cinema of the 1930s, recounting that one of the concerns with the cinematic representation of sinfulness was that it was made desirable by its supposed luxuriousness. Lily Powers gained her share of luxury, without doubt, and looks great while she’s at it. She may use her body, but the screen is only concerned with her clothing. In contrast, the only body we see unclothed is a man’s: exposed for all to see, there is without doubt a clear cut suggestion that it be used for sex.

Sex on screen

Again representing the freedom of the sexual being, Barbara Stanwyck says in Capra’s Ladies of Leisure, “Take a good look, it’s free.” This may be true, but as proven in Baby Face, go any further and one must pay a price. The men who take advantage of a naïve Lily get their comeuppance, (presumably) remaining directionless drunkards in small town Pennsylvania – though the politician is likely exempted. Once in New York City, that famous go-to place for the discovery and consolidation of success, Lily takes down a number of high-profile businessmen to get a leg up in society. It has been mentioned earlier but bears repeating: the clear message in this film is that women have as much right to be sexual, and get what they desire, as men (if not more, given how some men go about it). In an early scene of Ladies of Leisure, Stanwyck’s Kay Arnold changes clothes outside, guarded by nothing but the darkness of night. She tells a male onlooker to turn away, so he cannot see her; and although situated to the back of the screen she is visible to, although far away from, the spectator. Again, on screen, the female dictates the terms.

Columbia Studios publicity still for Ladies of Leisure.

In a book dedicated to the depiction and the censorship of sex in the cinema, Screening Sex, Linda Williams discusses the difference between kisses in pre-Code Hollywood and kisses afterwards, affected by its restrictions. The introduction to her book states:

During this prolonged adolescence [of the Production Code], carnal facts of life were carefully – often absurdly – elided, but also, as a result, much wondered about. Only since the 1960s has sex ceased to be the officially unmentionable, invisible energy of so much that attracts us to film. [14]

This argument cannot account for all of the delights of pre-Code cinema. Williams continues that the films of the Production Code do not feature kisses to “[b]ask in the glow of the anticipation of the sex to come.” [15] Yet while it is true that the Code prohibited any glorification of sexuality, there was always an underlying tinge of indulgence in sexual pleasure. In Platinum Blonde, the casual kisses between Anne and Smith are more than indulged in; they are enjoyed. Just as explicit are the direct references to an extramarital affair between Cary Grant and Loretta Young, and her multitudes of other partners, in Born To Be Bad (Lowell Sherman, 1934), which was made on the cusp of the Code. In Baby Face, the image of Chico happily strolling away while singing, “…leads a man by her apron string…” is indulgent and fairly obvious, not to mention Barbara Stanwyck’s perpetual glow throughout the whole film, which shines especially when she knows what she is about to do to a man. “I’d like to have a ‘Mrs’ on my tombstone,” she tells Courtland (George Brent), her future husband. When he hesitates, she says easily, “It needn’t last forever, you can divorce me in two weeks.” This statement, more than the most explicit image in Hollywood those days, basks in the glorified scene of sex and sin that preceded it.

The female body could be seen and enacted as something free from the confining structures enforced by the larger whole of society, and was unrestrained by the stipulations of the still-nascent Code. Indicative of the new freedom of present day society is the scene in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross (1932), in which Claudette Colbert is bathing in a large milk bath. In direct violation of so-called devout morality, her nipples surface not just once but several times as she dances about in the bath. With the grace of an Empress she demands that her minion Dacia (Vivian Tobin) take off her clothes and join her, and the camera frames Tobin’s feet while the dress slips off her body. There are plenty more nude bathing scenes in the pre-Code era, with harlot Jean Harlow bathing in a barrel in Red Dust (Victor Fleming, 1932), and in Hold Your Man (Sam Wood, 1933), when Clark Gable walks in on her, and when she quickly reappears in the next room and we know that she is wearing nothing but a dressing gown. Gable follows suit and joins her in his own bathrobe, in good fun but no doubt in the eyes of the censors, indecorous. In Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (Rouben Mamoulian, 1931) when Jekyll (Fredric March) first meets Ivy (Miriam Hopkins), her sassiness shows on screen; she clearly decides Jekyll is attractive and worthy of her time, and lifts up her dress, placing his hand on her garter. While the next few moments are rendered only in ellipses (in accordance with the Code), it is clear that she undresses and gets under the covers in bed; when her blanket slips, her breasts are clearly visible. In these moments, the female body is not displayed for anyone’s pleasure and is mostly indicative of a woman’s comfort.

Joan Crawford’s prostitute Sadie Thompson in Rain (Lewis Milestone, 1932) is a confidently sexually alluring figure in an otherwise quite serious and sober melodrama. She is first introduced by her hands, then her feet, individually framed as she steps through a doorway, and her face is the last to follow her through. Seductively, she greets a group of marines, and we know that she has no qualms about committing sin: “Make the best of things today because they can’t be worse tomorrow. Besides, I like the boys here,” she says. Adapted from a short story by W. Somerset Maugham, Rain follows a plot in which a morose missionary, Mr. Davidson (Walter Huston), converts Sadie to religious repentance and then rapes her (while this is obvious, the event is given a broad elliptical rendering). Davidson commits suicide the next morning, and this is not only deeply critical of religious hypocrisy but also further suggests the immoral attitude of men towards women. Sadie returns, appearing on screen again as she did when first presented, introduced with her jewelled hands and high-heeled feet as a woman who unapologetically glamorises herself and feels wonderful about it. With Rain, Sadie’s prostitute goes unpunished, unrepentant, and moves forward to a better place (Sydney – so perhaps she could be merely chasing the convicts) with a man whom she loves. Unlike Baby Face, money and class rise are not issues in Rain, but both women remain in fairly positive positions and their (glamorous) bodies are coded on screen as the source of their power.

In Williams’ words, Joseph Breen accepted that “a physical relation can be suggested as long as it is possible to deny it.” [16] This may have been his wish, but in many cases during the Code, Breen’s denial was nothing more than wishful thinking. It is for this reason strange that Baby Face was censored after Warner Bros had completed it and the amorality of the Nietzschean philosophy was removed through re-editing. But considering the rest of the film, this dialogue and the ellipses of sex scenes couldn’t have really covered up too much that was considered wrong with the film. (In his article on the discovery of the original print in the New York Times, Dave Kehr writes that Warner Bros did not receive an explanation of reasons for the rejection of the film, “perhaps because they seemed obvious enough.”) [17]

When such a response was formed regarding the original print of Baby Face it is understandable to wonder how the film was made in the first place. Firstly, there may have been the precedent set by MGM with Red Headed Woman, but, as the newspaper Hollywood Citizen-News wrote at the time, “Somehow MGM, more than any other producing company, has a way of getting around the critical prejudices of Will Hays.” [18] Secondly, it appears that Wingate had his own input: “[T]he fact that Barbara Stanwyck is destined for the leading role will probably mitigate some of the dangers of her in view of her sincere and restrained acting,” he had written. [19] Her acting may have been sincere and restrained, although she could have been quite infamous for her roles prior to Baby Face. She clearly had her own say in her character’s driven licentiousness and social positioning, and as Andrew Klevan writes of many of her roles in her body of work, “her character is rooted in such a way that forbids condescension, and becomes transcendent.” [20] Mick LaSalle is right when he says that, in the era prior to the 1940s, directors were not more important than their actors because “in most instances, the stars and producers called the shots”. [21] He includes a mantra cited by actress Dorothy Mackaill, that the modern girl has “tremendous vitality of body and complete emancipation of mind. None of the old taboos…mean a damn to us. We don’t care.” [22] Critics and publications were celebrating the “good bad girl,” and with this in mind it seems that Wingate’s idealisation of Stanwyck’s reputation was misdirected. Her acting style is marked by its sincerity, but there was always pleasure to be found in the glorification of ill repute.

Conclusion

In Baby Face, the undeniable flair with which sex is suggested leans towards that of the waning of the Code’s stronghold on the industry, when filmmakers were finding joy in pulling away from their restrictions. Not only is Lily’s history of sexual experience (as abuse, rather than consent) laid bare in the film’s opening minutes, each subsequent encounter is visually signposted by the fulfilment of her own desire to move up in the world – to change positions, so to speak. Even though the accusatory dialogue rarely implies her sinfulness beyond calling her “a girl of your sort,” it is hardly an equivocal sign when she reapplies her lipstick and follows a male pursuer out of the office ladies room. The entire thing is gleefully obvious, even in the face of the censorship applied to the film before it was granted release. Or at least it must have been to almost everyone but the staunchly naïve and morally orthodox bureaucrats in the censorship department. In his memoirs, Hays has written in exasperation that:

Both the Studio Relations Committee and I were roundly upbraided by press and public. The review of Baby Face in Liberty Magazine was headed: ‘Three Cheers for Sin!’ One newspaper columnist asked if the Studio Relations Department had ‘been out to lunch all year’. [23]

If only that were the case! Films in the pre-Code era such as those referenced in this essay were daring, explicit in innuendo, and brazenly critical of the status quo. Even a seemingly tacked-on ending like that of Female (Michael Curtiz, William A. Wellman, 1933) can be read as a sarcastic criticism of assigned gender roles in the patriarchy. But it is certainly apparent that the attempts of industry censors to filter sin out of Hollywood and their clean cut USA were to some degree successful. Although it had been gathering resolute Christian masses throughout the United States of America, the National Legion of Decency was formally established on April 11, 1934. Its members pledged that they would condemn “vile and unwholesome moving pictures” that were “corrupting public morals and promoting a sex mania,” and were opposed to what they considered a growing vehemence for a “filthy philosophy of life”. [24] The official decrees of the Production Code Administration put a stop to the release of any films that, in a nutshell, were aggressively or even modestly offensive to something rather arbitrarily labeled “correct standards,” an appropriately shady term that gave censors near free range to attack whatever they felt necessary.

According to Doherty, “Hollywood undertook a wholesale depoliticizing of its subject matter and a desexualization of its atmosphere, language, and bodies.” [25] Content and characterisation developed in a new direction, one that was very knowing of the power of metaphor. Hollywood responded to the manipulatively nebulous intent of the PCA with its own version of vagueness, and turned illicit content into decades of coded genius. So perhaps Miriam Hopkins’ garter in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde shifts in image and becomes Barbara Stanwyck’s anklet in Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944), but it is no less tempting. Importantly, both of these feminine accoutrements still deemed the woman in control of her own appearance, allowed her to define her own body and present herself as she desired.

The ending of Baby Face provides a nice symbolic representation of the woman as she was before Breen came in and stripped her of her independence. Lily Powers continues always in control right up until her final affair. When she decides that she loves the man she has married, she is signified to give up her promiscuity and settle. But she already has everything she wants – money, clothing, a home, a man (although she might have to give up the material, it is unlikely she won’t be able to wile it back) – and she also has the upper hand. In the opening minutes of the film we see only the muscular torso of a man, his identity irrelevant. In the closing minutes, it is her husband’s body, covered up with a hospital blanket that is the focus. Having mastered herself over them, men are no longer a threat to Lily, and she is as free to be as sexual as she desires, without sin. It is a small victory, but puts the pre-Code woman on top.

Notes:

[1] Jacobs, Lea, 1991. The Wages of Sin: Censorship and the Fallen Woman Film, 1928-1942. Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, p. 11.

[2] Jacobs, The Wages of Sin, p. 23.

[3] LaSalle, Mick, 2000. Complicated Women: Sex and Power in Pre-Code Hollywood. New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, p. 1.

[4] This was identified in documents found in the Warner Library of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theatre Research. Maltby, Richard, 1986. “Baby Face, or How Joe Breen Made Barbara Stanwyck Atone for Causing the Wall Street Crash”, Screen, 27: 2, p32.

[5] Jacobs, The Wages of Sin, p. 23.

[6] Doherty, Thomas, 1999. Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930-1934. New York: Columbia University Press, p. 132.

[7] Jacobs, The Wages of Sin, p. 82.

[8] Jacobs, The Wages of Sin, p. 82.

[9] Jacobs, The Wages of Sin, p. 175n35

[10] In the original version, the entire scene remains intact, including the shot of gloves.

[11] Jacobs, The Wages of Sin, p. 70.

[12] Doherty, Pre-Code Hollywood, p. 109.

[13] Smith, Ella, Starring Miss Barbara Stanwyck, New York: Crown Publishers, pp. 54-5.

[14] Williams, Linda. 2008. Screening Sex. Durham, London: Duke University Press, p. 2.

[15] Williams, Screening Sex, p. 4.

[16] Williams, Screening Sex, p. 41.

[17] Kehr, Dave, “A Wanton Woman’s Way’s Revealed, 71 Years Later,” The New York Times (January 9, 2005): http://www.nytimes.com/2005/01/09/movies/a-wanton-womans-ways-revealed-71-years-later.html?mtrref=www.google.com.au&gwh=2A53BEF5B98299106B215EED2345D141&gwt=pay

[18] Vieira, Mark A., 1999. Sin in Soft Focus, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc, p. 90.

[19] Vieira, Sin in Soft Focus, p. 148.

[20] Andrew Klevan, 2013. Barbara Stanwyck, London: BFI Palgrave Macmillan, p. 24.

[21] LaSalle, Complicated Women, p. 2.

[22] LaSalle, Complicated Women, p. 76.

[23] Hays, Will, 1955. The Memoirs of Will H. Hays. New York: Doubleday & Company, pp. 448-9.

[24] Doherty, Pre-Code Hollywood, pp. 320-1.

[25] Doherty, Pre-Code Hollywood, pp. 337.