‘Peak’ Production

Between 1958 and 1959 four significant international/transnational feature-film productions were made in Australia: On the Beach (Stanley Kramer, 1959), Summer of the Seventeenth Doll (Season of Passion, Leslie Norman, 1959), The Siege of Pinchgut (Harry Watt, 1960) and The Sundowners (Fred Zinnemann, 1960). [2] In many respects, this represents a period of peak production ‘down under’ prior to the near cessation of feature filmmaking that occurred in the early to mid-1960s. [3] The final of these films, Zinnemann’s episodic pastoral The Sundowners, released in the United States in early December 1960, is the last large-scale feature film made in Australia prior to Michael Powell’s They’re a Weird Mob in 1965-66 and represents the final completed attempt to make a high budget, mainstream and multi-star-driven popular success in Australia – other than the very differently appointed Ned Kelly (Tony Richardson) in 1970 and The Man From Hong Kong (Brian Trenchard-Smith) in 1975 – until the tax concession-driven push of the early 1980s. This essay revisits and reframes The Sundowners as a key work in the ‘transnational’ phase of Zinnemann’s career, while also re-examining the film’s production and reception, representation of place or geography, position within international film production models of the period, and direct influence on seminal works of the 1970s Australian feature-film revival such as Sunday Too Far Away (Ken Hannam, 1975). It also explores the place of The Sundowners within various discourses of Australian national cinema.

Three of the four films mentioned above are based on significant and widely successful Australian literary properties and reflect a maturing of locationist film production practices as well as the broader trend of independent production companies, with the support of major Hollywood and sometimes British studios, optioning bestselling novels and widely performed plays. For example, the decision to make a version of Ray Lawler’s ground-breaking and distinctively Carlton-set play, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, in the more cosmetically attractive hot-house climes of Sydney Harbour, drawing on a varied array of performance styles and starring a startling mix of American and British actors including Anne Baxter, Ernest Borgnine, John Mills and Angela Lansbury, was predicated on the international success and exposure of the source material and its apparent correspondences with thematically and stylistically equivalent US models such as Marty (directed by Delbert Mann in 1955, and also starring the Oscar-winning Borgnine) and the work of Tennessee Williams, then a popular source for screen adaptations including A Streetcar Named Desire (Elia Kazan, 1951), Baby Doll (Elia Kazan, 1956) and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (Richard Brooks, 1958). It is also symptomatic of the increased desire and capacity of Hollywood-based actors, writers, directors, producers and other significant filmmaking personnel to seek to control the means of production and make films largely outside of immediate studio jurisdiction. [4]

Although The Sundowners was made for Warner Bros. – with combative studio head Jack Warner even visiting the Southern New South Wales (NSW) locations early on in filming, after initially requesting that the movie be made in Arizona with a few kangaroos and other Australian fauna flown in [5] – it was also designed as an independent production. It reinforced a shift in Zinnemann’s filmmaking practice to a peripatetic form of transnationalism; a mode of production he never subsequently retreated from. This is illustrated by his ensuing films Behold a Pale Horse (1964), set in Franco’s Spain but shot in southwest France, and the multi-award-winning ‘British’ production, A Man For All Seasons (1966).

This transnationalism is reflected in many aspects of the production of The Sundowners. The film’s choice of locations illustrates both a genuine attempt to represent a range of Australian settings and the geographic necessities of reining in the scope of production: Cooma, Nimmitabel and Jindabyne in the NSW Highlands, south of Sydney; Port Augusta, Hawker, Whyalla, Quorn, Iron Knob and Carriewerloo in South Australia [6] ; and the subsequent studio interiors shot at Elstree Studios in London. Like each of Zinnemann’s films from the previous year’s The Nun’s Story (1959) onwards, The Sundowners illustrates the filmmaker’s desire to move beyond a mode of production largely confined to California and the broader US. Over the last 25 years of Zinnemann’s career, up until his final film, Five Days One Summer (1982), his work took him to places such as the Belgian Congo, France, Italy, Britain, the Swiss Alps and, of course, Australia. In this regard, The Sundowners is both a truly distinctive film and very much a reflection of the dominant forms of production developing at this time and fully embraced by Zinnemann.

Setting the Wheels in Motion

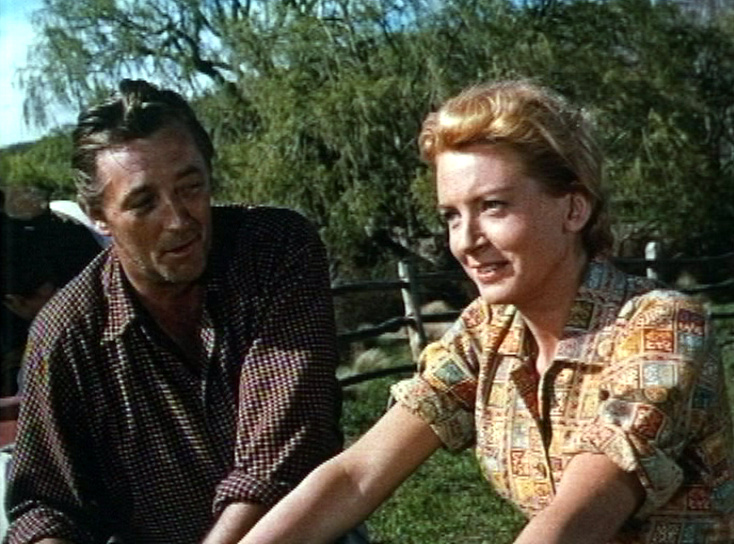

The Sundowners features a leisurely, almost itinerant narrative set in the mid-1920s that follows the trials, tribulations and daily activities of the Carmody family as they travel across parts of NSW and South Australia (though the actual locations are fictionalised for the movie). Although a deep sympathy between Ida (Deborah Kerr), Paddy (Robert Mitchum) and their son Sean (Michael Anderson Jr.) is emphasised, the narrative’s major conflict revolves around each of the characters’ desires for and definitions of home and place. On their journeys, the Carmodys meet up with a range of characters including Rupert Venneker (Peter Ustinov), an English remittance man who becomes their travelling companion and fellow drover. Amongst the episodes of the subsequent loose narrative are various scenes set in small-town pubs, featuring brawls and various forms of gambling, a raging bushfire, the recurring temptation of a riverside farm, the pregnancy of the wife of a young shearer (Bluey, played by John Meillon), the difficulties of a property owner’s upper-class wife to adjust to life outside of the city, and the two situations that become the major structural threads of the film: the itinerant life of the shearing season and Paddy winning a racehorse in a game of two-up. The change of the horse’s name from the novel’s “Our Place” to “Sundowner” in the film draws attention to a partial shift of focus in the adaptation away from the underlying tensions in the family and onto broader conceptions of belonging and community. This is also highlighted by the more incorporative vision of family and community found in the movie. For example, Venneker takes his leave from the family in the novel but continues to ride with them into the ‘sunset’ at the end of Zinnemann’s film.

Like On the Beach, based on Nevil Shute’s deflating international bestseller, The Sundowners represents a nuanced and faithful adaptation of its source material, especially when compared with the somewhat histrionic, narratively compromised, overly melodramatic but still often affective adaptation of Summer of the Seventeenth Doll. The Sundowners was based on the fourth novel published by then US-based Australian writer Jon Cleary. [7] Although Cleary continued to write popular novels until the early 2000s, The Sundowners was by far his most commercially successful work, becoming a significant bestseller in the US and elsewhere in the world. A sign of the novel’s success in Australia was its weekly serialisation in the Sydney Morning Herald in late 1952 and its adaptation for radio starring Rod Taylor in 1953. It was also selected as a “book of the month” in the US and went on to sell several million copies worldwide. Cleary’s book has undergone numerous editions and has rightly received very positive critical appraisal for its distinctive and detailed rendering of environment, situation and the Australian vernacular. [8] The rights were initially sold to US producer Joseph Kaufman as a key plank in an ambitious slate of potential productions planned in the wake of the first CinemaScope feature shot in Australia, Long John Silver (Byron Haskin, 1954), and its simultaneously shot TV series. [9] The commercial and critical failure of Long John Silver quickly undermined the possibility of any future production by this company. The rights to Cleary’s novel were subsequently picked up by Zinnemann at the suggestion of Oscar Hammerstein’s Australian-born wife, Dorothy, around the time of the director’s commercially successful though somewhat ill-matched adaptation of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! (1955). [10]

Initial plans for Zinnemann’s production started to emerge in early 1957 with the announcement of Deborah Kerr and Gary Cooper in the lead roles. [11] At this point in time, other actors such as Errol Flynn were suggested for the main supporting parts eventually taken up by Peter Ustinov and Glynis Johns (ultimately replicating the mix of British and US talent found in Summer of the Seventeenth Doll). At this stage, the plan was to start production in 1958, prior to Zinnemann embarking on the highly ambitious The Nun’s Story. This earlier date would have positioned The Sundowners as the first of this small group of international productions shot in Australia at the end of the 1950s, but a range of delays, including Cooper’s continued ill-health, led to production being stalled until late 1959. This delay allowed Zinnemann more time to survey potential locations, undertake significant research into period detail and contract other actors as well as spend time capturing initial footage of the landscape and the droving of sheep prior to the arrival of the full production crew and actors in October 1959. [12]

In regard to this careful attentiveness to filming in Australia, and how it sits in pointed contrast, for example, to Twentieth Century-Fox and Lewis Milestone’s very opportunistic Kangaroo (1952) completed earlier in the decade, Zinnemann should be placed alongside Harry Watt, Michael Powell and even Stanley Kramer as ‘sympathetic outsiders’ who spent time and effort to authentically capture the Australian idiom and environment. This attention to detail is also reflected in the subsequent decision to send a number of the Australian actors such as Chips Rafferty and John Meillon, as well as six actual shearers, to London for the studio-shot interiors at Elstree Studios in Borehamwood. [13] This division between location-staged shooting in Australia up until mid-December 1959 and London-based studio production in early 1960 places the film within the mainstream of transnational moviemaking in this period. The combination of US (or Hollywood), British and Australian actors and production personnel also reflects these broader practices. Nevertheless, in contrast to an expertly synthesised film like The Shiralee (Leslie Norman, 1957), which uses doubles, carefully disguised framing and clear demarcations between exterior and interior locations to minimise the transcontinental movement of actors, The Sundowners aims for a more lived-in, immersive and porous representation of space and place. [14] This is further reflected in the core theme of The Sundowners revolving around the notion of home as well as the decision to send a variety of Australian actors and types to Britain to ‘authentically’ populate and thicken the interior scenes.

An Australian Film?

Like many of the feature films made in Australia during the 25-year-period after World War II, The Sundowners is a difficult work to properly place in terms of broader understandings of Australian and international cinema. The film has many correspondences with earlier international films such as The Overlanders (Harry Watt, 1946) and The Shiralee that deal with itinerant outback life, and is an important precursor to the distinctive focus on recessive masculinity in many of the films of the 1970s revival. As Quentin Turnour has argued, The Sundowners has particular affinities with Sunday Too Far Away, one of the key films of this revival, and was even partly shot in some of the same locations, including a specific shearing shed in the South Australian town of Quorn. But as Turnour has also claimed, the two films are very different in terms of their representation of space and place and the ways in which character and community are situated within each: “[The] Sundowners’ town streets, public bars and even private rooms are populated in a way no Australian film ever was”. [15] Whereas Sunday Too Far Away is marked by a melancholy sense of solitariness and emasculation, while still giving some sense of the shared community and mateship of the shearers, The Sundowners gives us little sense of the vast distances between places or the depopulation that marks them. For example, aside from a somewhat stunted staging of a bushfire [16] – a potentially spectacular action set piece severely compromised by the unseasonably wet and cold weather encountered during the filming of these sequences in the Southern Highlands of NSW – the droving of the sheep is largely elided. The focus on backbreaking labour and the arduous repetition of work that dominates Sunday Too Far Away and The Overlanders is also little in evidence. As Turnour argues, The Sundowners tends to overpopulate both exterior and interior locations such as the shearing shed, the rowdy and crowded pubs, and the main streets of towns. [17] But rather than seeing this as a fault, these qualities emphasise the distinctive focus found in both the novel and film on notions of community, domesticity, home and family. As Zinnemann himself said, what attracted him to Cleary’s novel was that it “had the feelings of a love story between two people who had been married a long time. I thought it was marvellous to see, for once, people who’ve been married for fifteen or eighteen years and stayed in love with each other under very rough circumstances”. [18] In this regard, the film de-dramatises and underplays this conflict and, as clearly claimed in some of the Australian publicity that appeared during production and on its initial release, delivers a “story that’s heart-warming and exciting – full of the tingle of adventure and the very breath of life itself”. [19]

Like many of the films made during this period, the critical reception of The Sundowners is also marked by ambivalence about its characteristic representation of Australia and Australianness. Although it was generally well received both within Australia and on international release, criticism was raised about the episodic and leisurely nature of its narrative, its curious mixture of heightened realism and broad comedy, lack of dramatic incident and somewhat clumsy emphasis on stereotypical fauna such as kangaroos, wombats, parrots and galahs, especially in its earlier sections. The last of these elements was even highlighted in the title, “The Sight of Green Galahs”, of Sylvia Lawson’s significant review that appeared in Nation when it finally received its Australian release in December 1961. [20] Lawson’s astute critique of the film is an important precursor to her later calls, in seminal essays such as “Not For the Likes of Us”, [21] to establish a truly Australian mode of filmmaking not beholden to the favours and whims of international film production companies and studios:

It is horrifying – that we should have to be so touchingly grateful to Warner Brothers for giving this continent a pat on the head, for throwing a few pink galahs on the screen, for showing us ourselves, or our country cousins, in terms proper to folksy radio-serial or the domestic comic strip. Those gasps of joy were the clearest possible demonstration that we need our own film industry to show us who and what we are. [22]

Despite such understandable criticisms, the film was generally praised and went on to be nominated for five Academy Awards: Best Film, Director, Adapted Screenplay, Actress and Supporting Actress. It has subsequently been singled out for the honesty and experiential emphases of its lead performances, particularly those by Kerr and Mitchum, as well as the careful attention to detail found in Zinnemann’s fastidious direction and Jack Hildyard’s bucolic cinematography. It is also remarkable in the broader context of transnational film production in Australia in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s in that it is a work signed by a director at the peak of his career starring actors of significant box-office allure at the time the movie was made (the only comparative work is the much more sombre and explicitly self-important On the Beach). [23]

Lawson’s critique does raise more significant questions about the validity of the film’s treatment of landscape and environment: “One might regret more the way the outback seems to be gentled, scaled-down and tidied-up. Encountering such distances, most people are challenged and altered. The landscapes could have been used with so much more intensity, they could have been images of inner space as well”. [24] These criticisms are relatively inarguable, but they also misread the intentions of the film and book. Although the lives of the three central characters are tough, wearing and physically difficult, the key tension in the film and novel is between different conceptions of community and home, not the faltering of these concepts against the bitter isolation of the outback. In some respects, this is a refreshing vision and even domestication of the Australian landscape that has closer affinities with the backwoods comedies and melodramas of Ken G. Hall than heightened psychological ‘landscape’ dramas such as Sons of Matthew (Charles Chauvel, 1949), Jedda (Chauvel, 1955), Walkabout (Nicolas Roeg, 1971) and Wake in Fright (Ted Kotcheff, 1971). Cleary’s novel does give a clearer and more nuanced sense of the growing bitterness and weariness of Ida, her and Sean’s need to tie themselves to a more grounded sense of home, and the mindless distances travelled between gleanings of a broader communal existence, but both novel and film are ultimately triumphant portraits of the resilience of character and community. While the inner and outer conflict between the three characters is emphasised – and also placed into relief by the serial dalliances and romances of Venneker, the various women condensed into the figure of Mrs. Firth (Glynis Johns) in the film – there is little sense of a broader existential battle between figure and environment. The novel does present a stark reminder of the hostility of the Australian landscape in the burning out of the Batemans’ property, but this family’s hardy response reinforces the concept of resilience and deep connection to the land as well as the specificity of place. The Sundowners is a work profoundly concerned with the diurnal patterns and realities of everyday life and the deep relationship of character to environment.

Lawson’s highly critical approach to The Sundowners needs to also be seen in the context of an emerging cultural nationalism as well as arguments for a truly ‘Australian’ mode of feature film production. The film’s reception in the early 1960s and beyond should also be viewed in relation to the rising tide of auteurist film criticism and, more specifically, director Zinnemann’s fate at the hands of important writers on auteurism like Andrew Sarris. [25] Although these emerging analytical frameworks had little direct impact on the initial critical reception of the film, one can sense a particular critical consensus around Zinnemann emerging in reviews by important critics such as Penelope Houston in specialist film journals like Sight and Sound. [26] Zinnemann was one of the most respected and awarded Hollywood directors at the time of the film’s production, but his subsequent critical reputation has been devalued for what is generally regarded as an overly fussy and even ‘academic’ focus on detail, [27] the lack of a distinctive visual style and a quietness, coolness and reticence with regards to the outward expression of emotion. He has largely fallen victim to the damningly applied epithet of ‘craftsman’: “The word ‘craftsman’ has been tattooed to his chest like a scarlet letter, a sign of public meticulousness and pedantry”. [28]

Zinnemann himself has expressed an antipathy towards the excesses of auteurism – while still very much promoting himself as the author of his films – emphasising his own ability to adapt to a particular story, environment, collaborative team or sensibility. Nevertheless, over the last 20 years, a number of attempts have been made by fine writers such as Robert Horton and J. E. Smyth to rehabilitate Zinnemann’s reputation as a director marked by a distinctive set of thematic preoccupations (centred around notions of resistance and the relation of personal morality and ethics to a broader community) and a fastidiously attentive approach to the details of gesture, action, environment and performance. [29] Although The Sundowners is often discussed as one of Zinnemann’s most successful and nuanced films, it is generally situated outside of the corpus of his key works. For example, Smyth’s focus on the theme of resistance, a concept that marks Zinnemann’s personal experience as a Jewish émigré with extended family in Europe as well as specific films like The Seventh Cross (1943) and The Nun’s Story – set during or immediately before World War II – leaves little space for discussion of a seemingly peripheral and less outwardly personal film like The Sundowners. It is only when the film is placed within the broader practice of transnational filmmaking, an approach and sensibility that was integral to Zinnemann’s work since making the documentary drama Redes (Waves) in Mexico with Emilio Gómez Muriel and photographer Paul Strand in 1936, that it moves to the centre of his oeuvre. But The Sundowners’ focus on “individual conscience”, [30] personal choice and the ramifications and impact of a particular ‘philosophy of life’ – unbendingly expressed by Paddy through his refusal to settle down – also draw it closer to the mainstream of Zinnemann’s output.

“Bush Week”: Travelling Back in Time

The Sundowners opens with a leisurely long shot of a horse and carriage trundling towards the camera before panning to the right to register the gentle movement of the characters through space. The opening three shots, over which the credits appear accompanied by Dimitri Tiomkin’s folksy but affective score, matter-of-factly establish location, scale, period (as a 1920s car passes the anachronistic horse and carriage), character, pace and sensibility. There is no sense that what we are about to see and hear will be rushed or even tightly framed or organised, though it will have a composed and highly burnished pictorial beauty. Although the general period of the film is established in these shots and the following scenes – by the car, an offhand reference to Buster Keaton, etc. – there is a sense of unhurried timelessness and even solipsism established here. This sense of being out of or going back in time was central to the marketing of the film and Zinnemann’s own impressions of Australia:

I found the Australians at that time [1959, when the film was shot] to be like the Californians in my time thirty years earlier, very simple people with a primitive, very warm sense of humour. You couldn’t call them naïve, but they were very insular. And they knew what they were about and were very honourable. [31]

Although the film basks in a kind of bucolic naturalism or realism, it also communicates a sense of insularity in relation to the outside world. There is little sense given of broader national or even global concerns, and the legacy of World War I, the ingrained racial policies of ‘White Australia’, and emerging workers’ rights have little impact on the various episodes and conflicts depicted. In contrast to Sunday Too Far Away, which was mostly set just prior to the 1956 shearers’ strike, unionism and workers’ rights are only briefly touched upon – in the comic scene where the men are chauvinistically deciding whether to take on Ida as a cook at the shearing station, a moment directly matched in Sunday Too Far Away – and are largely discounted by the breezily utopic but still highly segregated vision of gender, labour and benign management that develops at the station. Although there is space and time given to the depiction of labour, the mutually desired separation of workers and bosses, much of the daily grind and repetition of droving, shearing and life on the road is elided by the narrative’s focus on such stereotypical Australian elements and events as a two-up game, further practices of gambling, horse racing, a shearing contest, numerous bouts of drinking at the pub, a young expectant mother who travels to the shearers’ camp and tests the mettle of the women she finds there (all of whom rise to the task) and of her own husband. For a film that aims at granting a real sense of the diurnal rhythms of the life of the sundowner, it shows little of the isolation, physical hardship and true economic deprivation that underline this existence. Unlike films such as The Shiralee or even The Overlanders, each of which are suspicious of fixed notions of home, community, the city and the exploitation of the land, The Sundowners emphasises the importance of home and the various ways it can be configured, situated and redrawn.

Immediately following the credits, and after a brief set of exchanges that help situate the specific locale the characters are about to enter as well as the attitudes they hold towards it, Sean, Paddy and Ida set up camp on the banks of a river looking over the verdant spread of an idyllic farm nestled in the NSW Southern Highlands near the Snowy Mountains. The following scenes reinforce many of the values outlined throughout, particularly the warm sense of humour and the ease of the relationships between the characters. These scenes also set up the clipped, gently mocking tone of the conversation, alongside the colloquial peculiarities of the Australian vernacular. Both Mitchum and Kerr manage to approximate, throughout, the modulations of the Australian accent and speech patterns, and the dialogue is peppered with distinctive slang and colloquial expressions. These include the liberal use of words and terms like “flamin’”, “darl’”, “g’day” and “beaut”, and less straightforwardly translated expressions like “cow cockies”, “bush week” and “shickered”. The dialogue closely follows that found in Cleary’s novel and provides evidence of his role as a script consultant or editor asked to reintroduce the Australian vernacular to Isobel Lennart’s “mid-Pacific” script. [32] Although lively, affectionate and leisurely, these opening scenes establish and reinforce the carefully composed nature of the film.

These opening passages also bring to the fore a range of other themes, conflicts, visual preoccupations and physical relationships that will preoccupy the film. As already mentioned, the film’s portrait of a married couple is quite remarkable and although the strength of this bond is tested by different desires and hard-won expectations, the resilience, carnality and physicality of the couple’s union is never really put into serious question. This marital bond is demonstrated in a remarkable later scene at the shearing station when Ida warns her son against taking sides against his father: “Sean, you’ve got your whole life to live. We’re half way through ours, your Dad and me. There’s other people waitin’ for you but there’s no one waitin’ for us except each other. Don’t ever ask me to choose between you and your Dad, because I’ll choose him every time”. This exchange also highlights the tripartite nature of the film’s narrative, its focus on the dynamic of a small, unevenly formed family, the particular journeys taken and tests faced by each of its central characters, as well as its matter-of-fact focus on generational change and the process of ageing. In many respects, this is clearer in the novel, where Sean’s journey from childhood to the cusp of adulthood is explicitly set up as one of the key narrative threads, the one mostly keenly observed in relation to the alternative father figures (Venneker and Bluey) offered to Sean. That said, there are still significant remnants of this comparison in several of the exchanges in the film, including the final parting between Bluey and Sean where the former expresses his hope that his newly born son will grow up to be like young Carmody.

Although not over-emphasised in either film or novel, the passing of a particular way of life, of being in the landscape, is documented and nostalgically remembered in The Sundowners. It is fairly clear that the Carmodys will someday need to settle down, though their home may be no less precarious than their tirelessly moving wagonette. As Venneker loquaciously states in the final passages of the novel:

You’ve been on the road a long time, but I don’t think you’ll finish up like most sundowners. Most of them never reach the end of their road. But you will, Sean. Just keep plugging away. Never mind the disappointments you’ve had … just go your own way with your eye on what you want, and you’ll get there. [33]

There is also a grounded sense of nostalgia for a lost time and place that is highlighted in the novel’s spare final words: “Long Island, Sept. 1950 – Aug. 1951”. [34] This closing, subtly smuggled-in declaration of time, place and distance recognises the novel as a memory work written from a vastly different point in time and space. It also helps to further situate and justify the nostalgic perspective of Zinnemann’s film and its transnational qualities and characteristics.

Hollywood-Australia: Mitchum and Kerr; Men and Women

Zinnemann’s film also shifts further emphasis and focus onto Ida while generally and more pointedly observing the place of women. The carnality and physicality of Ida and Paddy’s marriage is established in these early scenes, somewhat crudely but efficiently introduced through a set of exchanges about Ida’s backside. The film is clear-eyed and up-front about establishing the healthy sexual relationship that exists between the couple. This is reinforced by the expression of a clear mutual respect and comfort between the two actors who had previously worked together on John Huston’s Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison (1957) and went on to co-star in two further productions: the considerably less salubrious The Grass is Greener (Stanley Donen, 1960) and the TV-movie Reunion at Fairborough (Herbert Wise, 1985). Some reviewers found Kerr miscast as the earthy, unvarnished and confidently sexualised Ida. But this limited understanding of her prim star persona, pointedly dissected in a film like Otto Preminger’s Bonjour Tristesse (1958), discounts the sexual yearning bubbling just beneath the cloaked exterior of Sister Clodagh, her breakthrough role in Black Narcissus (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1947), or forgets the harder-edged sexual frankness of her portrayal of the worldly but vulnerable Karen Holmes in Zinnemann’s From Here to Eternity (1953). Kerr singled out her role in The Sundowners due to its departure from the typical characters she had previously played: “She’s a typical female really, no sentimentality at all. I haven’t had a part like this before; it’s quite new. Oh, I know I’ve played dowdy people, but the sheer physical roughness of this part is something different”. [35] But despite this, Zinnemann also rightly criticised attempts to market the film in relation to Kerr’s eroticism and the chemistry apparent in the previous onscreen coupling of the two actors. [36] Kerr’s performance as Ida is up-front, no-nonsense and relatively undemonstrative. She is the one who initiates sexual relations with Paddy and her desires are naturalised rather than overly erotised. They become a necessary and ritualised part of daily life – nothing more or nothing less.

In retrospect, the one aspect of the film that has received almost universal acclaim is Mitchum’s performance. This is reflected in the sometimes-surprised contemporaneous reviews, but can be neatly summarised by the following appraisal from Mitchum’s biographer, Lee Server: “As Paddy Carmody, a living, breathing creation without a hint of artifice or theatricality, Mitchum gave perhaps the greatest demonstration of his supreme command of a naturalistic acting technique that was as rare as it was – generally – underappreciated”. [37] This view of Mitchum’s grounded, unfussy, laconic qualities as an actor, and how they are embodied in his performance as Paddy, was shared by both Cleary – “Robert Mitchum is anything but a droopy-eyed slob once you get to know him. He is extremely well read and writes beautiful poetry” [38] – and Zinnemann: “Bob is one of the finest instinctive actors in the business”. [39] These highly positive responses to Mitchum’s performance sit in contrast to many accounts of the film’s production that highlighted the actor’s demonstrable unease with the overbearing attention showered on him by a clearly starstruck Australian public and the difficulties associated with the locations used and the climate encountered. Mitchum’s apparent problems on location reflected popular preconceptions of his combative star persona. This is demonstrated and somewhat confounded by the publicity interview that appeared in The Australian Women’s Weekly during production: “When I went to see Mitchum, I expected I might find someone boorish and uncooperative, I found instead someone just the opposite – helpful, polite, and extremely intelligent”. [40] Mitchum’s reputed dislike of his time in Australia was capped off by his hounding by the Australian tax department in relation to his earnings on the film. [41]

The opening scenes also set up the core theme of home and the various ways it can be defined. At this juncture, Paddy’s reluctance to settle down as well as his desire to keep moving are seen as minor points of conflict. The characters look across the river to the idyllic farm that is evidently available for sale. But rather than this being set up as a contrast between the sedentariness and solidity of the farm beckoning across the ceaselessly flowing river and the itinerant lifestyle of the sundowners, we are shown, instead, two different ideas of home and community. Paddy’s flight from the financial burden of a mortgage and the spatial restrictedness of a bordered property is not a retreat from his family, his responsibilities or the concept of home. Home for him is the camp that the three of them set up every night and that dominates the film much more than their itinerant life on the road. There are also things to commend, particularly from a contemporary viewpoint, about Paddy’s refreshing desire to only ever tread lightly on the land. For a film about characters who supposedly live their lives on the road between sun up and sundown, The Sundowners spends an awful lot of time with them in camp, in town or gathered together in conversation. As Paddy openly suggests, their home is the landscape.

But as has been emphasised throughout this essay, The Sundowners is also a transnational film that attempts to address a broad potential audience and meet its narrative expectations. This is reinforced, of course, by the various decisions made to cast internationally recognised American and British actors in the main roles (and only Ustinov’s Venneker matches the nationality of character and actor). The film also contains elements that are reminiscent of the Western and specific domestic frontier films like Friendly Persuasion (William Wyler, 1956). But The Sundowners also addresses and exploits its exoticism as a rendering of the under-represented landscape of Australia. The initial moments do not provide a clichéd or even particularly characteristic image of the Australian landscape – the environment is largely green and shot in the mountain areas of NSW around Jindabyne – and the use of the Australian vernacular is evident but not overly pronounced or explained. But such images and sounds do start to creep in, though they are largely isolated to the earlier sections of the film. The decision to string together a series of shots of various birdlife including cockatoos, galahs and kookaburras, soon to be followed by kangaroos, koalas and wombats either mixing with the sheep or fleeing a raging bushfire, self-consciously addresses the need and desire to distinguish and exploit the identifiable local fauna. But unlike Kangaroo, for instance, this does not extend to the Indigenous inhabitants of the land. Aboriginal characters and figures are largely absent from The Sundowners and only appear at brief moments when bringing the sheep into the shed or interacting with each other in the background of specific shots at the shearing station. This is both a strength and weakness of the film. These isolated and unheard figures are normalised and not exoticised, but the film also shows no curiosity towards these ‘backgrounded’ characters (in fairness, neither does a film like Sunday Too Far Away). This stands in, largely grateful, contrast to the earlier Kangaroo. Although the early shots of various Australian animals and habitats suggest that the film will wearily display a cornucopia of stereotypical Australian elements and icons, these clear markers of distinctive nationality and place are de-emphasised in the later sections of the film.

Selling The Sundowners

The novelty of filming in Australia was highlighted by the film’s marketing, along with the personas of its various stars (such as Kerr’s sexually frank role in From Here to Eternity and her previous collaboration with Mitchum), its appeal to character-based realism and Zinnemann’s track record as a director of highly-awarded films sometimes shot in exotic or at least ‘foreign’ locations (such as Hawaii for From Here to Eternity and the Belgian Congo for The Nun’s Story). This somewhat muddled collection of selling points can be traced back to the film’s theatrical trailer. In a very noticeable American accent, the trailer’s voiceover opens by proclaiming: “This is down under, the fascinating continent of Australia. And these people [accompanied by brief shots of Kerr, Mitchum and Johns] are of that rare breed you’ll find nowhere else: the sundowners”. Elsewhere, the novelty of the film’s setting is explicitly emphasised: an “untold story of a new kind of people … [a] new kind of motion picture experience”. This way of promoting the film feeds into the uncommonness of its setting and the diurnal, everyday rhythms of its tight-lipped, laconic drama. Although the epic nature of its setting and narrative is emphasised here and in the main US release poster, this claim that it provides a “new kind of motion picture experience” also prepares audiences for the peripatetic journey of its characters and the “drama” of their daily existence. Kerr has suggested that part of the reason for the film’s relative failure at the US box office was due to its prescience in terms of this dramatic emphasis. [42] In this respect, Kerr sees the film in relation to the emerging European art cinema of its era as well as the more episodic and de-dramatised Hollywood movies that appeared in the mid to late 1960s: “It was a little before its time. It was a no-story movie – an observation of life, with a marvellous cast”. [43]

This brings us back, though through a more positive frame, to the “gentled, scaled-down and tidied up” rendering of the outback landscape opined by Lawson and that highlights and helps to stage the small-scale interior dramas of the characters. [44] This is the personalised realm that the film unapologetically deals in. A great illustration of this dramatic economy is found in its most remarked-upon scene. For instance, the highly enthusiastic reviewer for Variety hyperbolically called it a “fleetingly eloquent scene at a train station … that ranks as one of the most memorable moments ever to cross a screen”. [45] This brief sequence features an exchange of furtive glances between Ida, grimy faced and perched on a wagon, and an elegantly dressed woman travelling to the city, or a larger town, on a train. The original exchange of dialogue covering several pages is transformed into a simple contrast between the costume, situation, spatial confinement and mode of transport and address of these two never-introduced characters. It is very difficult to read the response of the woman on the train to Ida’s gaze or to her appearance, but Kerr gives a wonderfully subtle expression of both defiance and extreme longing in this moment. It is as if she sees the memory of another kind of life pass by.

While the trailer introduces each character in terms of the physical sensation they will generate in the audience – “You’ll bask at the warmth of Ida. With all that beauty under a coat of dust” – it also highlights the novelty of the physical environment we are about to experience: “for two unforgettable hours you’ll go along with The Sundowners, living a rich lusty life you’ve never known before”. The tone and mode of address of this trailer suggest that the studio and the filmmakers were well aware of the kind experiential and immersive portrait they had on their hands. The trailer does show us some of the scenes featuring local flora and fauna, but it also emphasises the naturalistic and physical relationships between its characters: “Glowing with the flavour and excitement of special people and real passions”. In its understandable attempt to appeal to both male and female audiences, the trailer concludes with superimposed titlecards riding roughshod over the subtler dimensions of the film’s careful staging, plotting and even promotion: “For every man who ever wanted to wander and every girl who wanted to follow him … until she could pin him down … this is the motion picture!”

These overtly dramatic elements and emotions are equally emphasised by the film’s key US release poster. This highly composed image combines multiple shots of incidents from the narrative against the background of the shooting flames of a bushfire. The poster also highlights the erotic and sexual nature of Kerr’s character and her broader star persona (she is shown both in bed and wearing a slip in two of the separate images that make up this collage, a somewhat unrepresentative vision of her character in the film). Meanwhile, the hyperbolic lead tagline is not afraid to over-claim the drama of the film’s narrative or the felt distance that the characters travel: “HERE COME ‘THE SUNDOWNERS’! They’re real people, fun people, fervent people. They have a tremendous urge to keep breathing. Their rousing story comes roaring across six thousand miles of excitement …”. I guess this was indeed a welcome contrast to those films that featured characters who didn’t “have a tremendous urge to keep breathing”. Though, perhaps, that was a genuine point of appeal after the creeping nuclear annihilation of the previous year’s On the Beach shot in Melbourne.

An “untold story of a new kind of people”

Although The Sundowners features familiar and even clichéd flora and fauna, landscapes, character types, colloquial expressions and slang, it is still not commonly regraded as a key work of Australian cinema. For example, in his survey of the sparsely populated terrain of Australian feature filmmaking between 1930 and 1960, Bruce Molloy offhandedly devotes just half a paragraph to Zinnemann’s film, merely claiming it “ranks as one of the more successful attempts by foreign filmmakers at evoking a genuinely Australian atmosphere, possibly due to its setting in the bush … and to its concern with distinctively Australian occupations such as droving and shearing”. [46] In contrast to other significant international productions of the post-war era like The Overlanders, Bitter Springs (Ralph Smart, 1950), They’re a Weird Mob, Walkabout and Wake in Fright, The Sundowners is considerably more reserved in its exploration of national character, identity and the drama of the Australian landscape. It sits as a genuinely mature and transnational film that draws significantly upon the expertise of American, British and Australian personnel and reflects dominant trends in large-scale international production at the time it was made. As is evident from its somewhat schizophrenic marketing campaign, it was and has been a difficult film to conceptualise and place within broader understandings of Australian and international cinema. Promoted as portraying “a rich lusty life you’ve never known before”, it is equally remarkable for its depiction of the rhythms of everyday life and the “tremendously good-natured” [47] quietness of its narrative and central performances. Although it is highly responsive to the specificity of environment, situation and character, it also works hard to universalise these localised elements while respecting the necessary demands placed upon it by its Australian audience. The Sundowners reflects the characteristic care and attention to detail found in Zinnemann’s internationally focused and produced work, but still sits a little precariously between the demands of international and national cinema. As Graham Shirley and Brian Adams matter-of-factly claim about this balancing act, “With The Sundowners … came a worthy successor to The Overlanders as a visitor’s film that captured some genuine national sentiment without appearing to overreach itself”. [48] These are qualities that we should not undervalue.

NOTES:

[1] The review of The Sundowners in Variety is generally positive while claiming, “On paper, the story sounds something short of fascinating”. This mildly deflated perspective resonates with the film’s subdued critical reputation in Australia. See Tube, “The Sundowners”, Variety (2 November 1960), p. 6.

[2] These four films are routinely included on lists of locationist or offshore productions made in Australia from 1945 until the early 1970s, a period of very limited home-grown feature filmmaking. This approach or designation fails to adequately recognise the significance of many of these films to Australian cinema as well as the truly collaborative and transnational nature of several of the productions, including The Sundowners. I use the terms ‘international’ and ‘translational’ to recognise the complex histories, identities and uses made of many of these films. The term transnational expresses the inadequacy of discourses of national cinema to account for what Higbee and Lim term “an increasingly interconnected, multicultural and polycentric world”. See Will Higbee and Song Hwee Lim, “Concepts of Transnational Cinema: Towards a Critical Transnationalism in Film Studies”, Transnational Cinemas, vol. 1, no. 1 (2010), p. 8. The Sundowners, along with a number of other international films made in Australia in the pre- and post-war era, suggests that these shifts towards transnationalism and globalism are evident from a much earlier moment. For a further discussion of the increasingly significant and porous relationship between Australian and Asian cinemas, see Olivia Khoo, Belinda Smaill and Audrey Yue, Transnational Australian Cinema: Ethics in the Asian Diasporas (Maryland: Lexington Books, 2013).

[3] For example, no Australian-made feature films were released in either 1963 or 1964.

[4] Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, for instance, was made by the Hill-Hecht-Lancaster production company and was distributed by United Artists.

[5] Fred Zinnemann, An Autobiography (London: Bloomsbury, 1992), p. 174.

[6] These two states dominate international studio production in Australia during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.

[7] Cleary also worked on the scripts of The Sundowners and The Siege of Pinchgut. A large part of his role on The Sundowners was to reintroduce the distinctly Australian atmosphere and laconic dialogue to the shooting script. The sole-credited scriptwriter, Isobel Lennart, had downplayed these elements. See Jon Cleary, “Introduction”, The Sundowners (HarperCollins: Sydney, 2013), p. xi.

[8] The novel’s revered status is demonstrated by its inclusion in HarperCollins’ “A&R Australian Classics” series in 2013.

[9] Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film, 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, rev. ed. (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 219.

[10] See Zinnemann, 173. Zinnemann’s autobiography is characteristically cool and relatively unrevealing about the finer details of the film’s production. He also claims that Dorothy Hammerstein had originally intended to send him a copy of D’arcy Niland’s then just released The Shiralee (1955) rather than Cleary’s book. The Shiralee was subsequently and very successfully adapted into a film by Ealing Studios in 1957.

[11] “Deborah Kerr in Australian Film”, The Sydney Morning Herald (20 April 1957), p. 3.

[12] It is relatively easy to spot the difference between the grainier documentary-style material shot before the arrival of the full cast and crew and that captured during the main period of production.

[13] See “Six Shearers Get Film Trip to U.K.”, The Australian Women’s Weekly (13 January 1960), p. 7.

[14] For a discussion of how The Shiralee and the four other Ealing films made in Australia manage location, setting and emerging international modes of production, see Adrian Danks, “South of Ealing: Recasting a British Studio’s Antipodean Escapade”, Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 10, no. 2 (2016), pp. 1-14.

[15] Quentin Turnour, “Lost in Space”, Metro/CTEQ Annotations on Film, issue 117 (1998), p. 68.

[16] The bushfire has a more central and devastating effect in Cleary’s novel. On their travels, the Carmodys visit with another family, the Batemans, whose house is subsequently burned out by the bushfire. This traumatic event, and what it communicates about the harshness of the Australian landscape and any human claims over it, does not carry over to the film.

[17] This crowdedness is also unlike one of the key visual references used for the production of the film, the sparsely populated and somewhat haunted paintings of Russell Drysdale.

[18] Zinnemann in James R. Silke, “Zinnemann Talks Back”, Fred Zinnemann Interviews, ed. Gabriel Miller (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2005), p. 13.

[19] This tagline was used to promote The Sundowners in some of the newspaper advertising appearing at the time of its first release in Australia.

[20] Sylvia Lawson, “The Sight of Green Galahs”, Nation, issue 84 (16 December 1961), p. 22. Oddly, Australia was one of the last major territories to release the film, a year after its US premiere.

[21] Sylvia Lawson, “Not For the Likes of Us”, Quadrant (May-June 1965), pp. 27-31.

[22] Lawson, “Sight of Green Galahs”, 22.

[23] Though it should be noted that neither Kerr nor Mitchum were ever listed amongst the top ten Hollywood stars in terms of box office for any particular year, they both featured in a large number of commercially successful films and sustained A-list careers for significant stretches of time.

[24] Lawson, “Sight of Green Galahs”, 22.

[25] Sarris was very critical of Zinnemann’s overly mannered, consciously liberal, craftsman-like, undemonstrative and gently tasteful body of work. See his entry under the damning category, “Less Than Meets the Eye”, in The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929-1968 (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), pp. 168-69. In contrast, Sarris’ common adversary, Pauline Kael, did offer some positive if brief comments on The Sundowners in her seminal essay, “Trash, Art, and the Movies”, in Going Steady (New York: Little, Brown, 1970), p. 108.

[26] Penelope Houston, “The Sundowners”, Sight and Sound, vol. 30, no. 1 (Winter 1960-61), pp. 36-7.

[27] Robert Horton, “Day of the Craftsman: Fred Zinnemann”, Film Comment, vol. 33, no. 5 (September 1997), p. 64.

[28] Horton gives an astute account of this term and how it has been applied to the director’s work in his appropriately titled, “Day of the Craftsman: Fred Zinnemann”, 62. Zinnemann also commonly called himself a craftsman.

[29] See J. E. Smyth, Fred Zinnemann and the Cinema of Resistance (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014).

[30] John Fitzpatrick, “Fred Zinnemann”, American Directors Vol. II, ed. Jean-Pierre Coursodon with Pierre Sauvage (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983), p. 379.

[31] Arthur Nolletti, Jr. “Conversation with Fred Zinnemann”, Film Criticism, vol. 18, no. 3 and vol. 19, no. 1 (Spring-Fall 1994), p. 25.

[32] Cleary was present for much of the shooting as evidenced by various production stills and contemporary accounts of the filming.

[33] Jon Cleary, The Sundowners (London and Glasgow: Fontana Books, 1969), p. 318.

[34] Cleary, The Sundowners, p. 320.

[35] Kerr in Michelangelo Capua, Deborah Kerr: A Biography (Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland, 2010), p. 127.

[36] Zinnemann, p. 183.

[37] Lee Server, Robert Mitchum: “Baby, I Don’t Care” (London: Faber and Faber, 2001), p. 352.

[38] Server, p. 350.

[39] Zinnemann in George Eells, Robert Mitchum (New York and Toronto: Franklin Watts, 1984), p. 221.

[40] Helen Frizell, “Mr. Mitchum Full of Surprises”, The Australian Women’s Weekly (14 October 1959), p. 5. Aspects of the film’s production, including interviews with the stars, profiles of the children featured and location reports filed by Frizell were covered in at least six stories published in The Australian Women’s Weekly between May 1959 and March 1961.

[41] Server, p. 353.

[42] Though these elements did not stop the film achieving significant box-office success in Britain or Australia.

[43] Kerr in Eric Braun, Deborah Kerr (London: W. H. Allen, 1977), p. 175.

[44] Lawson, “Sight of Green Galahs”, p. 22.

[45] Tube, p. 6.

[46] Bruce Molloy, Before the Interval: Australian Mythology and Feature Films, 1930-1960 (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1990), p. 38.

[47] Colin Bennett, “Films in 1961: A Vintage Year for Melbourne”, The Age (30 December 1961), p. 11.

[48] Graham Shirley and Brian Adams, Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years, rev. ed. (Sydney: Currency Press, 1989), p. 208.

Author Bio:

Adrian Danks is Deputy Dean, Media in the School of Media and Communication, RMIT University. He is also co-curator of the Melbourne Cinémathèque and was an editor of Senses of Cinema from 2000 to 2014. He has published widely in a range of books and journals including: Senses of Cinema, Metro, Screening the Past, Studies in Documentary Film, Studies in Australasian Cinema, Australian Book Review, Screen Education, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, Traditions in World Cinema, Melbourne in the 60s, 24 Frames: Australia and New Zealand, Contemporary Westerns, B is for Bad Cinema, Howard Hawks: New Perspectives, Refocus: The Films of Delmer Daves, Cultural Seeds: Essays on the Work of Nick Cave, Being Cultural, World Film Locations: Melbourne and Sydney, and Twin Peeks: Australian and New Zealand Feature Films. He is the editor of A Companion to Robert Altman (Wiley, 2015) and is currently writing several books including a monograph devoted to 3-D Cinema (Rutgers), a co-edited collection on the nexus between Australian and US cinema, and a volume examining “international” feature film production in Australia during the postwar era (Australian International Pictures, with Con Verevis, to be published by Edinburgh University Press).