Lottie Lyell was a much-loved silent movie star in the early days of cinema in Australia. She was also an accomplished scenario writer, director, film editor, and producer. Quietly working alongside director, Raymond Longford, she had a considerable influence on the twenty-eight films they made together. [1] Longford directed and Lyell starred in nearly all the films, but it is now generally accepted that she contributed a great deal more to all the films than was officially acknowledged at the time. [2]

This article builds on the existing research on Lyell through a focus on her work as a scenario writer. It also makes a contribution to screenwriting research through a study of some of the original scenarios held in the archives.

In her work on the Canadian silent screen star, scenario writer, director, and producer, Nell Shipman, Kay Armitage writes of the experience of original research in the archives and “the sense of the body of the subject as perceived through the sensorium of the researcher”:

… every time Shipman typed a capital, the letter jumped up half a line, and when she came to the end of a sentence, she hit the period key with such force that it left a hole in the paper … That it is Shipman’s body that we contact, rather than a simple fault in the machine, is proven when we read a letter written by Shipman’s husband on the same typewriter. [3]

My search for evidence of Lyell’s contribution as a scenario writer has meant looking for this “sense of the body” on the original scenarios and this has inevitably involved a degree of speculation.

Longford and Lyell

Longford was a good deal older than Lyell, a friend of the family and a married man. They were both stage actors and in 1909 when Lyell was nineteen, her parents put her in Longford’s care when they both toured New Zealand in the play An Englishman’s Home. [4] He was more experienced than her, but she was young and full of ideas and they shared a passion for storytelling and a keen interest in the new medium of the cinema. They soon formed a creative partnership that lasted right up to her untimely death from tuberculosis in 1925, aged thirty-five.

Figure 1 - Lottie Lyell (as Margaret Catchpole) in The Romantic Story of Margaret Catchpole. From the collection of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Their first film The Romantic Story of Margaret Catchpole (1911) was based on the true story of a woman convict transported to the penal colony of New South Wales for stealing a horse to help her lover escape. [5] It was a clever choice as both convict and bushranger films were proving popular in the colony, and by 1908 the activism of the early suffragettes had won votes for white women in all states of Australia. [6] When Lyell stole the horse, disguised as a boy, and bravely rode it pursued by the law, she rode into the hearts and minds of Australians looking for new kinds of heroines.

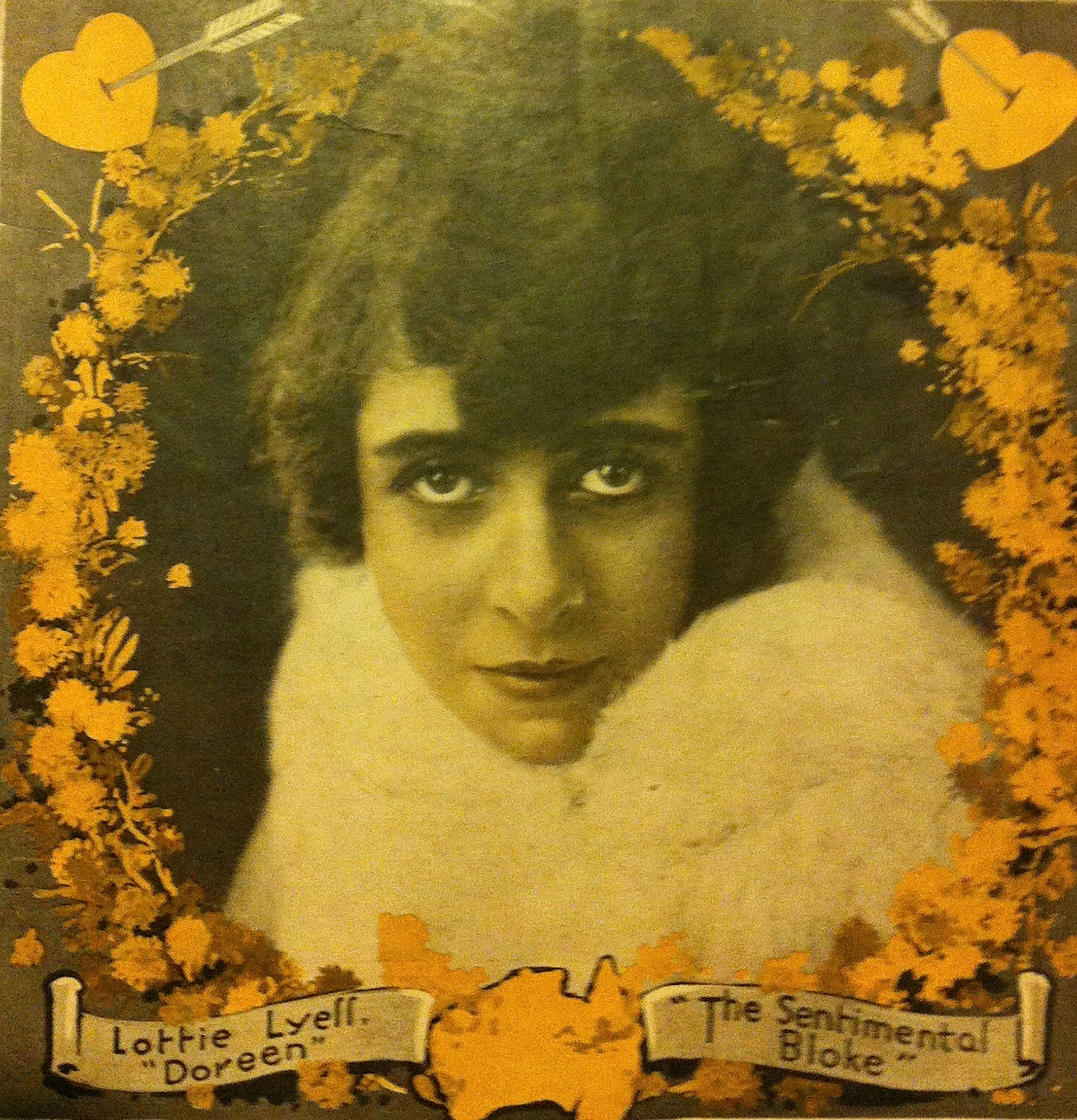

In 1958 in a short typescript memoir about their film The Sentimental Bloke (1919), Longford wrote: “The scenario, preparation, exteriors and interiors of the film were carried out in its [sic] entirety by Longford Lyell Film Productions – Lottie Lyell was my partner in all our film activities.” [7] Yet up until 1916 it is not Lyell’s name but Longford’s that is on all the scenarios. Only in that year is Lyell credited as co-writer on both A Maori Maid’s Love (1916) and The Mutiny of The Bounty (1916). Of the twenty-eight films they made together Lyell holds scenario-writing credits on twelve, just under half their combined output.

Figure 2 - Lyell and Longford on the set of A Maori Maid’s Love. From the collection of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Lyell had an understated performance style that showed a clear understanding of the new medium and the films were distinctive for the sophistication of their film language. Yet this grasp of film language is usually attributed to “Longford’s mastery of film technique” in his role as auteur director. [8] In his book The Secret Language of Film French screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière claims that:

An authentically new language did not emerge until filmmakers started to break the film up into successive scenes, until the birth of montage, of editing. It is here, in the invisible relationship of one scene to the next, that cinema … generated a vocabulary and grammar of unbelievable diversity. [9]

When Lyell started editing the films she would have quickly learnt this new ‘language’ and this, in turn, would have informed her work as an actress, a director, and a writer.

Asked if he thought Lyell played a significant role as a writer on all the films, Australian producer Anthony Buckley, who as a young man met and interviewed Longford, replied: “Without question: The Lyell fingerprints are over everything.” [10]

The Scenarios

The copyright requirements of the time required the scenario, along with a still photograph from each scene, to be submitted for copyright. Luckily this has meant that a number of the original scenarios, plus high quality stills, survive in the National Archives of Australia, whereas most of the films have been lost. Fragments of The Romantic Story Of Margaret Catchpole and The Woman Suffers (1918) exist in the National Film and Sound Archive, and in 1991 archivist Marilyn Dooley reconstructed The Woman Suffers from the surviving footage and the still photographs, using the existing scenario as a guide. [11] The Sentimental Bloke (1919) is the only film to survive in its entirety. [12] There is no surviving footage of Mutiny of the Bounty (1916) or The Church and The Woman (1917) but the scenarios and stills from both films are available for study.

Figure 3 - Eileen (Lottie Lyell) succeeds in getting out of the cellar in The Church and The Woman (1917). From the collection of the National Archives of Australia.

Given the sexual division of labour at the time it makes sense to assume that Lyell was the typist; that she typed while Longford dictated, but given accounts of their relationship it is probably closer to the truth to suggest that they discussed every aspect of the screenplay, while her hands were on the typewriter, forming words on the page and thinking about the images. In the early 1900s typewriter ribbons were available in black and various other colours, but according to the 1910 Remington typewriter manual, the latest models were “regularly equipped for using two colour ribbons” as well. [13] The usual combination was purple and red. Users could switch easily between the two colours. Copies could also be produced by using “rather thin paper” and placing a sheet of “semi-carbon” paper between the letter sheet and another sheet of thin paper. [14] Most of the scenarios I saw in the archives were typed in purple on rice paper that was so thin it was almost transparent, indicating perhaps the production of several typewritten copies.

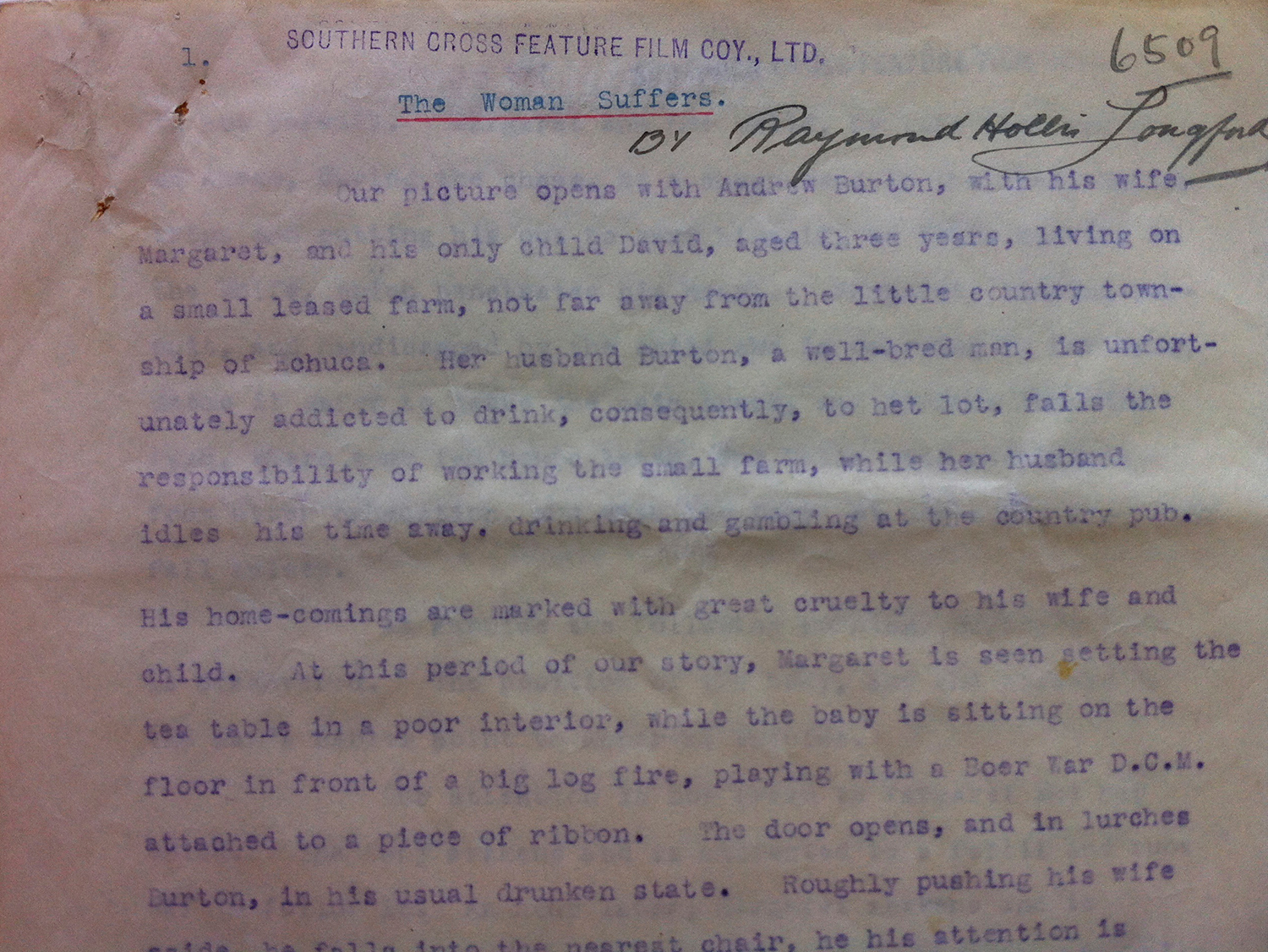

Figure 4 - Detail from The Woman Suffers scenario. From the collection of the National Archives of Australia.

The scenario for The Woman Suffers is typed in purple, but instead of a cover page the title is typed in blue and underlined in red on the first page. Perhaps the title was added to a carbon copy for the copyright submission and Lyell had a blue and red ribbon in the typewriter, but even this small fingerprint shows an attention to detail, as the position of the ribbon would have had to be changed in order to underline the title in red. Longford’s name as sole author of the scenario has been handwritten under the title, yet the first line reads: “Our picture opens with…”.

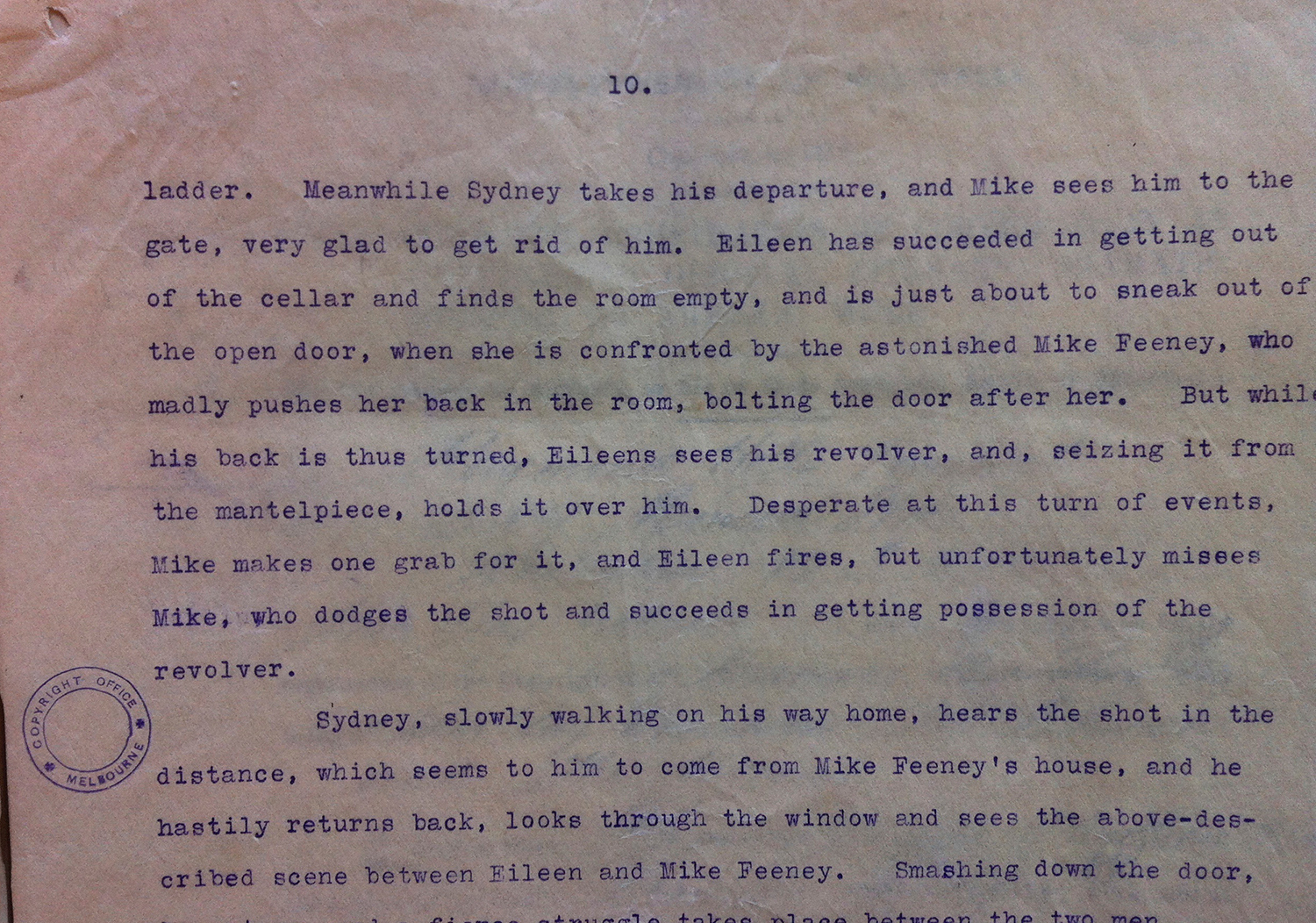

Silent films did not require written dialogue; they plotted out the story describing the action as necessary. Intertitle cards were included if exposition were necessary and these could always be rewritten later. This meant directors and actors could work freely on set, developing complexity through improvisation. Scenarios were therefore written with a different production process in mind. [15] They were also significantly shorter than the scenarios for talking pictures. The scenario for The Church and The Woman that survives in the archive is ten pages long, and written in prose.

Figure 5 - Detail from The Church and The Woman scenario. From the collection of the National Archives of Australia.

Figure 6 - Eileen (Lottie Lyell) sees his revolver, and, seizing it from the mantelpiece, holds it over him, in The Church and The Woman. From the collection of the National Archives of Australia.

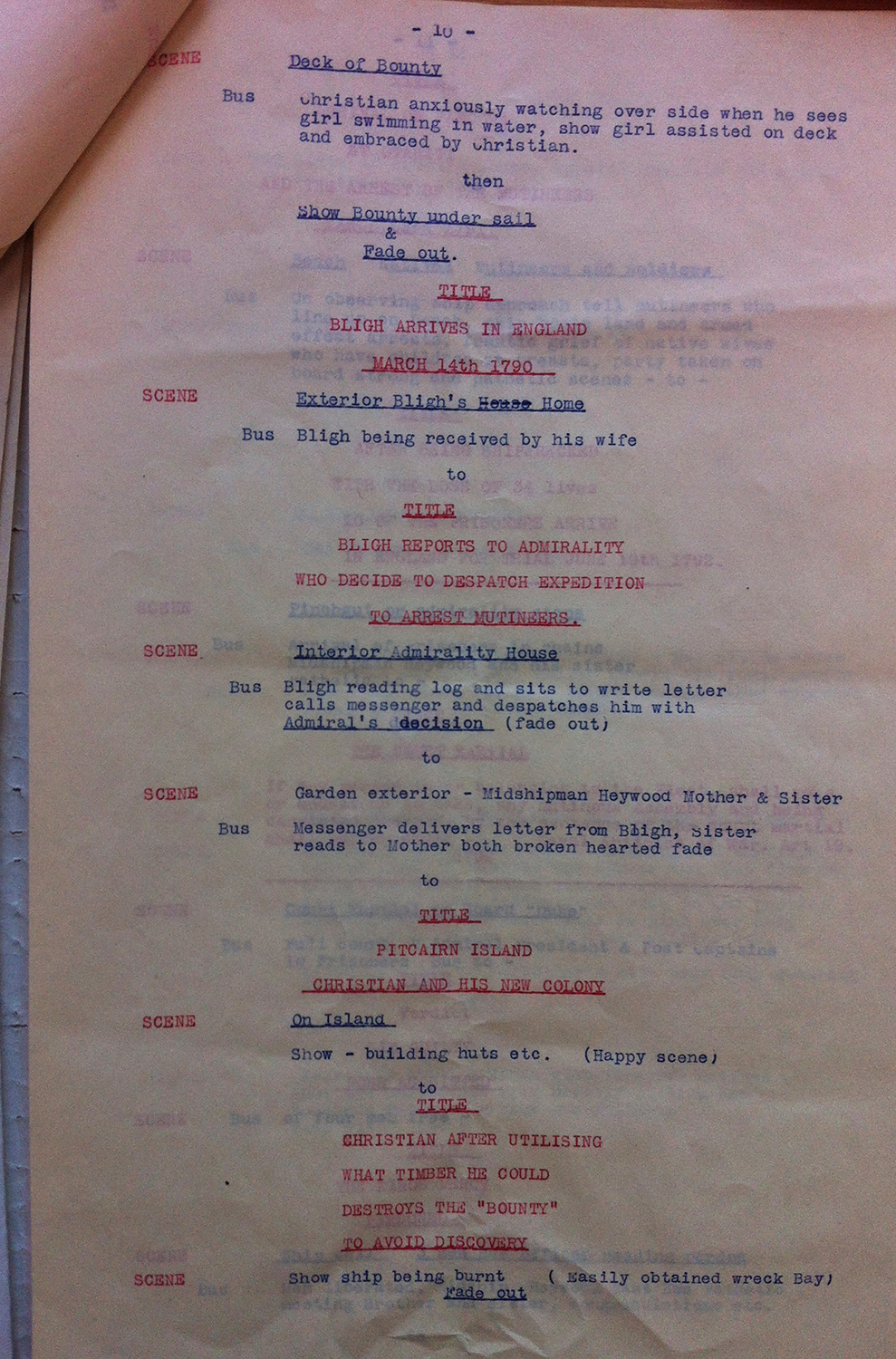

The scenario for The Mutiny of The Bounty is thirteen pages and in terms of format looks more like a modern screenplay. Scene numbers and locations are included along with intertitle cards, which are indented on the page the same way dialogue is now indented. The evolution of the modern screenplay can be traced back to these early scenarios where writers like Lyell adapted playwriting and silent film conventions to suit the new and evolving cinematic form.

Figure 7 - The Mutiny of the Bounty scenario p.10. From the collection of the National Archives of Australia.

The Mutiny of The Bounty was the second film for which Lyell received a co-writing credit, and the scenario, quite possibly the original document and typed with a two-colour blue and red ribbon, shows an artistic attention to detail that is distinctive. Red is used to denote scenes and title cards, and blue for locations and scene descriptions. If Lyell was the typist then this careful and time consuming use of colour to aid the formatting of the scenario is surely another fingerprint, as is the correction in figure 7 where “House” has been crossed out and “Home” has been substituted.

Also typed on delicate, almost translucent, rice paper, the scenario for Mutiny of The Bounty was a revelation. Pulling on white gloves and carefully picking it up in the hushed atmosphere of the archive, I had a powerful “sense of the body of the subject” as described by Armitage – of Lyell’s hands on the typewriter keys. The word “decision” has been typed with extra vigour!

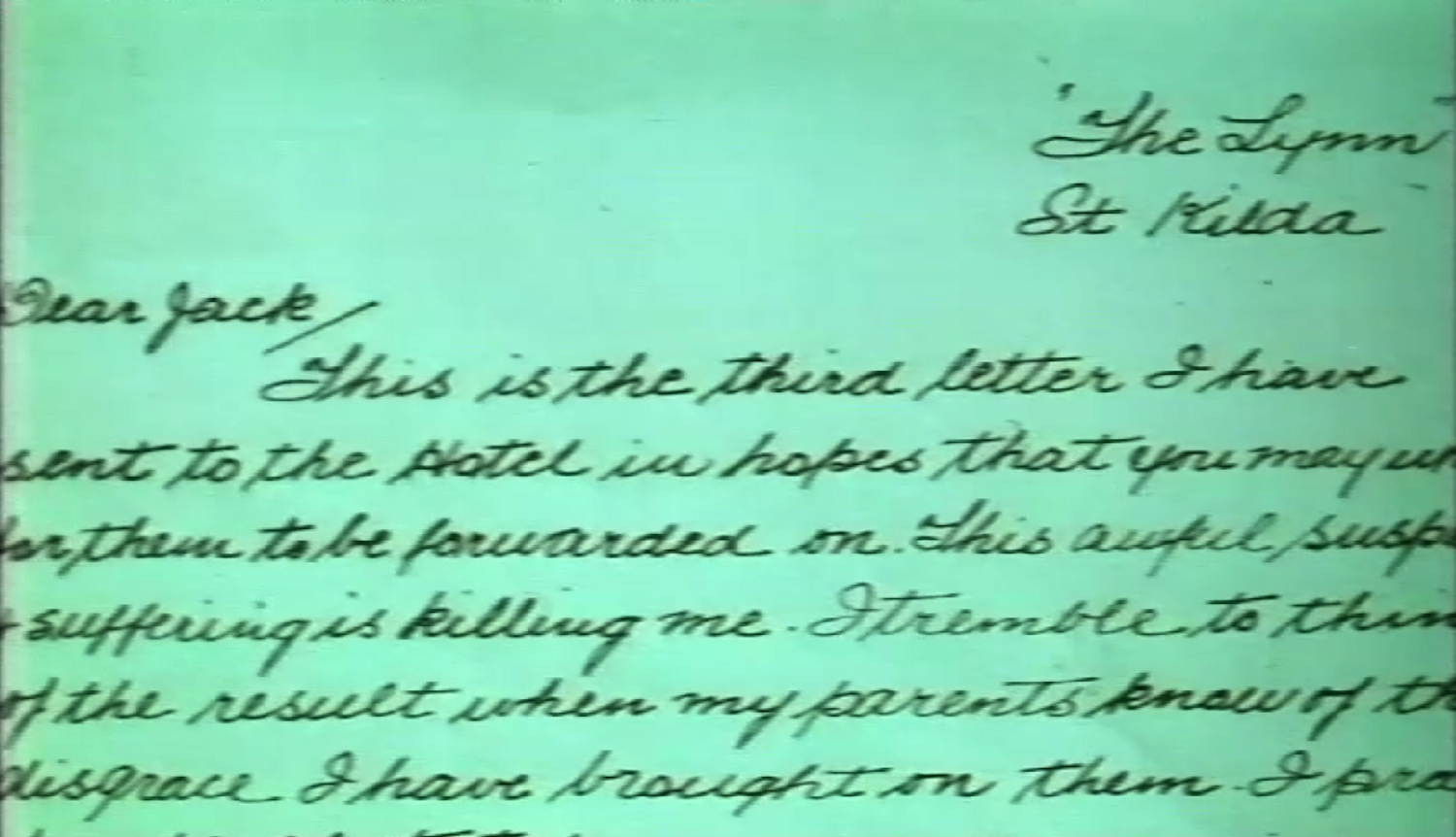

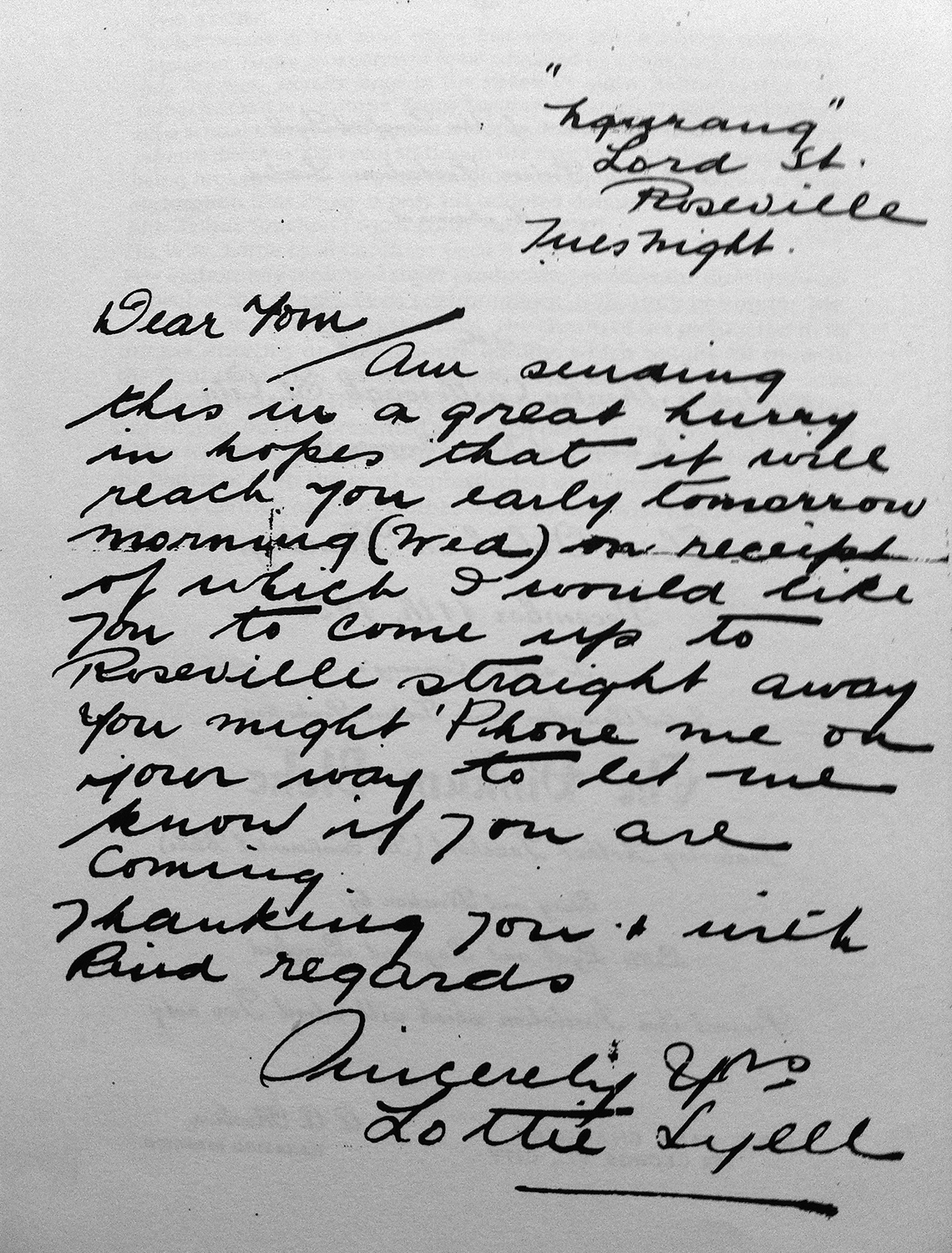

Longford and Lyell formed a production company in 1923 and Longford’s papers contain typed business letters, which show the same artistic use of two colour ribbons. Curiously none of Lyell’s papers have survived and apart from one letter and her signature on a few business letters there are no papers left to study. Silent films often used handwritten letters to convey exposition and Lyell’s handwriting is quite distinctive, particularly her Ds and Ls. Comparing the one surviving letter and the handwritten letters that appear on screen in The Woman Suffers, I quickly realised the handwriting was hers.

Figure 8 - Handwritten letter by Lottie Lyell. From the collection of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Dooley searched Longford’s papers, but found no sign of Lyell’s papers. She did however find a faded copy of the scenario of The Sentimental Bloke. The original scenario had been submitted to the NSW Police Department, as Longford wished to film an illegal Two Up game being raided by police, and needed permission. The police failed to return it and Longford’s papers contained correspondence, which led Dooley to the State Records Office of New South Wales where the scenario is still held. At forty pages it is the longest scenario they wrote and closer in length to a modern feature treatment, but it is more spaced out and has scene numbers down the left hand side like a stage script.

The Sentimental Bloke was an adaptation of C. J. Dennis’s poem of the same name and the hand-printed correction on page five where “woman ways” has been changed to “winnin’ ways” is correct. With Longford reading the poem and Lyell typing, perhaps this error was Longford’s ‘slip-of-the-tongue,’ which Lyell then had to hand-correct.

The last film Lyell and Longford made together was The Blue Mountains Mystery (1921). It was adapted from the 1919 Harrison Owen novel The Mount Marunga Mystery. Lyell holds the sole scenario writing credit as well as a co-directing credit. In a publicity photograph for the film (figure 12) she is depicted on set standing between cinematographer Arthur Higgins and Longford, her hands firmly on the script.

Figure 12 - Lottie Lyell and Raymond Longford (right) with cinematographer Arthur Higgins and lighting assistant on the set for The Blue Mountains Mystery. From the collection of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

The Mystery of the Missing Papers

The mystery of Lyell’s missing papers has never been solved. Perhaps some were destroyed in order to protect her in the lead up to a court case brought by Edward Finn in 1918 in relation to The Church and the Woman. [16] Finn successfully sued the producer of the film, Joseph Pugliese, for breach of copyright (and plagiarism) in relation to his novel The Priest’s Secret even though Longford had registered the film for copyright. Longford holds the sole writing credit on both The Church and The Woman and The Woman Suffers even though Lyell starred in both films, was clearly involved behind the scenes, and had received a co-writing credit on two previous films. Dooley notes:

That’s why I think the names of the screen characters in The Woman Suffers are different from the scenario. I think they adapted The Woman Suffers from a penny dreadful or some other novel of the time. [17]

Longford was the executor of Lyell’s will and her personal papers would have ended up in either his hands, or her mother’s. It was well known in film circles that Longford and Lyell’s relationship was more than a just a business one. [18] Longford’s Catholic wife refused to give him a divorce, but when Lyell’s father died, Longford moved into the house with her and her mother. Longford’s wife did finally agree to a divorce, but it didn’t come through until after Lyell’s death. Perhaps Lyell’s papers were destroyed because they proved she had lived a more sexually adventurous life like many artists at the time and, like the characters in The Church and The Woman and The Woman Suffers, would have been publicly condemned for this. Wright suggests that:

Possibly because Lottie Lyell lived outside the conventions of her time, she had the ability to question social attitudes. Her personal relationship with Raymond Longford endured for seventeen years although a formal marriage was never possible. [19]

Longford remarried after Lyell’s death and his new wife took charge of all his papers. It is possible she destroyed them, but it is also possible Lyell chose to destroy them herself.

Conclusion

Longford may well be credited as the sole writer on the majority of the scenarios, but the surviving documents reveal evidence of Lyell’s ‘fingerprints’ and stand as a testament to a collaborative writing process, which she clearly had a major hand in. A close study of the scenarios also revealed the exigencies of the silent film form as well as the seeds of the modern screenplay format.

Lyell’s death meant the end of a dynamic and creative partnership, and without her quiet counsel Longford faltered. He never again achieved the success of the early films and ended up a solitary figure working on the Sydney waterfront as a night watchman. [20] But it was also a difficult time for local filmmakers. The advent of talkies meant a massive increase in production costs and Australian filmmakers were increasingly unable to compete with the Hollywood juggernaut, which was dominating cinema exhibition and distribution.

The 1970s Australian film renaissance sparked renewed interest in the rich history of Australia’s silent era, and in the 1980s feminist film scholars began researching the role of women like Lyell. One of the problems with researching Lyell again is not just that there is a great deal of material already in print, but that her modesty and deference to Longford and the lack of any personal papers has created gaps and silences in history. Writing about the historical research for her book Alias Grace (1996), Canadian writer Margaret Atwood counsels:

What does the past tell us? In and of itself it tells us nothing. We have to be listening first before it says a word, and even then, listening means telling and retelling. [21]

My search for Lyell’s ‘fingerprints’ has meant ‘listening’ to the gaps and silences, particularly when the imprint of Lyell’s typewriter, or pen, opened up a space to ‘sense’ her body as a working writer, not just a silent partner.

After industry consultation, in 2014 the Raymond Longford AFI (Australian Film Institute) and AACTA (Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts) Award for outstanding contribution to the enrichment of Australia’s screen environment and cultures was changed to the Longford Lyell Award.

Endnotes

[1] Andree Wright, Brilliant Careers: Women in Australian Cinema (Sydney: Pan Books, 1986), 1-14

[2] Apart from Wright’s work of historical recovery in the above note, see also Andrew Pike, & Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900–1977 (Melbourne: Oxford University Press 1998), 19, 109, and Marilyn Dooley, Photo Play Artiste: Miss Lottie Lyell, 1890-1925 (Canberra:ScreenSound, 2000), 4.

[3] Kay Armitage, The Girl from God’s Country: Nell Shipman and the Silent Cinema (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003), 254, 256.

[4] Dooley, Photo Play Artiste, 9.

[5] The Romantic Story of Margaret Catchpole (dir. Raymond Longford, 1911, Australia).

[6] Bushranger films were so popular that between 1911 and 1912, the New South Wales, Victorian and South Australian governments banned them, concerned they were undermining the authority of the police. For an official précis of the history of Australian suffrage, see http://www.aec.gov.au/Elections/australian_electoral_history/wright.htm and http://www.aec.gov.au/indigenous/history.htm. Accessed 4 May 2015.

[7] National Film and Sound Archive Australia Title No 392164 Raymond Longford: Documentation: Assorted papers including correspondence, invitations and unrealized scripts.

[8] Graham Shirley and Brian Adams, Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years (North Ryde, NSW: Angus & Robertson, 1983), 55.

[9] Jean-Claude Carrière, The Secret Language of Film, trans. Jeremy Leggatt (New York: Random House, 1994), 8-9.

[10] Anthony Buckley, personal communication, October, 2012.

[11] The Woman Suffers reconstruction: NFSA Product, 1991, NFSA title: 274544

[12] Anthony Buckley, Dominic Case, Ray Edmonson, Andrew Pike, Raymond Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke – The Restored Version, (National Film and Sound Archive Australia 2009)

[13] Directions for Using the Remington Standard Typewriter: Models 10 and 11 6th ed. (New York: Remington Typewriter Company, 1910), 16; available in PDF from “The Classic Typewriter Page,” http://site.xavier.edu/polt/typewriters/tw-manuals.html, accessed 24 June 2015.

[14] Ibid., 31.

[15] Anthony Buckley, personal communication, 22 August 2012.

[16] For an example of news reporting on the case see The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 March 1918, reproduced at http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/15769889.

[17] Marilyn Dooley, personal communication, 24 August 2012.

[18] Wright, Brilliant Careers, 10, 11.

[19] Wright, Brilliant Careers, 10.

[20] Wright, Brilliant Careers, 13.

[21] Margaret Atwood, “In Search of Alias Grace: On Writing Canadian Historical Fiction” American Historical Review 103, no. 5 (1998): 15.