This essay distils some of the claims made in my book Go West, Young Women! The Rise of Early Hollywood. [1] That project mines the importance of Hollywood’s rise in the American West by exploring how this location became central to the first myths told about the film industry’s social significance. These myths – spun in advertisements, booster campaigns, newspapers columns, magazine stories, novels and eventually the movies themselves – influenced Los Angeles’ development as a particular kind of feminized boomtown during the 1910s and 1920s. The approach reveals Hollywood as central to the feminist ferment that erupted during the first two decades of the twentieth century. In the process, it de-familiarises a subject that many people think they know something about: Hollywood’s relationship to influencing young women’s aspirations and attitudes toward their emancipation in the twentieth century.

The dominant critical narrative about this subject stubbornly persists with the assumption that women played almost no role in shaping the fortunes of the American film industry as it developed into one of the largest and most visible industries in the world in the single decade between 1910 and 1920. Typically, most paint a picture of an industry built around a few powerful men – like directors D.W. Griffith or Cecil B. DeMille, or producers like Adolph Zukor or Jesse Lasky – teaching women to trade on their sexuality through consumer culture for other men’s pleasure. In doing so, the film industry has been charged for scripting a not so new “New Woman entrapped in a process of self-commodification.” [2]

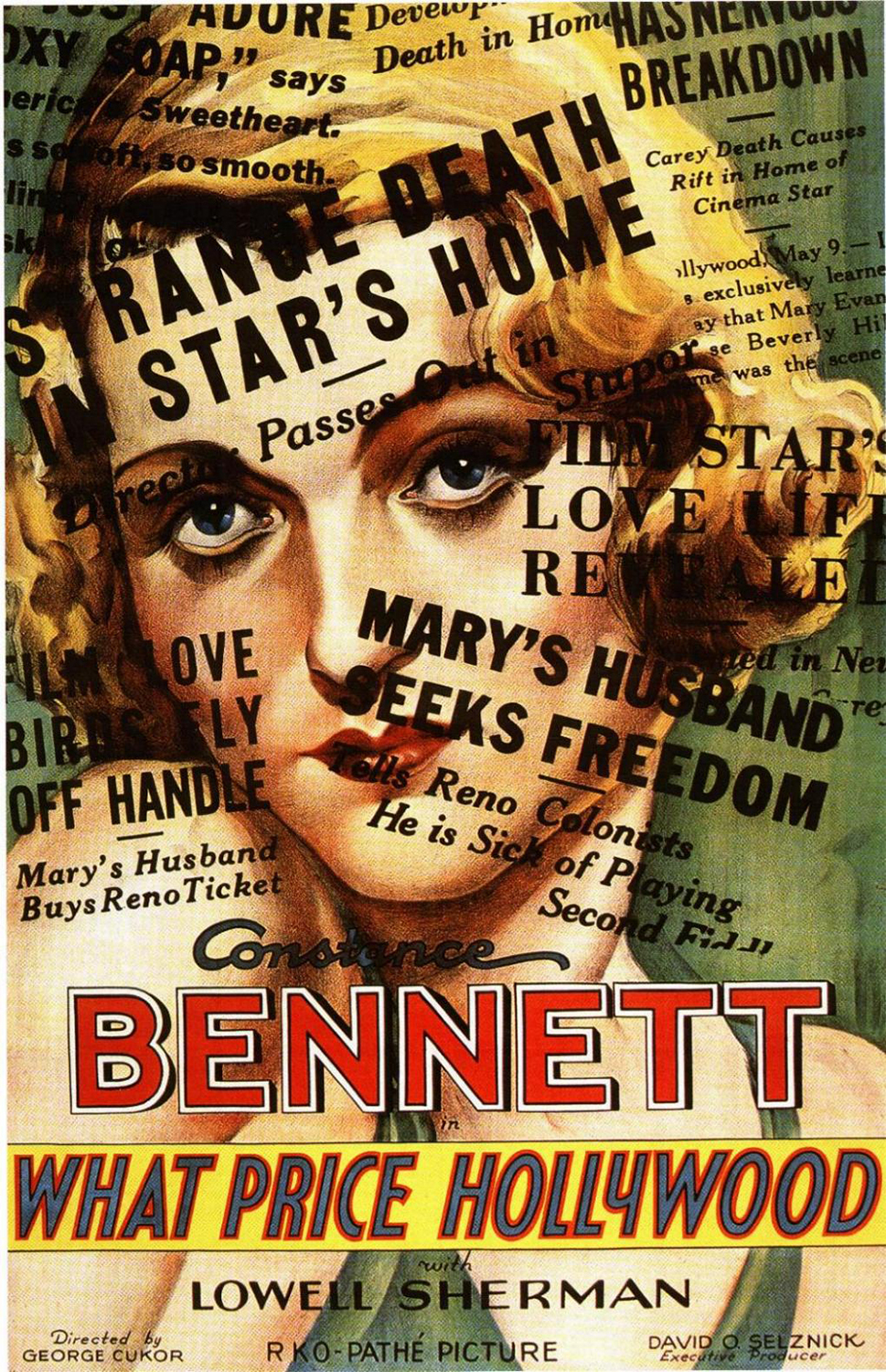

People know this story from film scholars, but more often from the media, including the versions advanced by the American film industry itself. Such stories have created a kind of subgenre that I think of as Hollywood femme noir. And the 1932 film What Price Hollywood? was an early and influential example of it. [3] (figure 1) What Price Hollywood? was based upon a 1926 short story of the same name written by Adela Rogers St. Johns, the journalist known as “Hollywood’s Mother Confessor.” [4] What Price Hollywood? became the basis for the film A Star Is Born, which was remade in 1937, 1954, and 1976. Each successive version of the movie depicts the effect of success in Hollywood on women as more and more tragic. All of the film versions distil the message of the Hollywood femme noir subgenre: to be a glamorous, professionally ambitious female was to become at best a ludicrous object, at worst a dangerous one. These movies also made clear that any woman who did not abandon her individualistic ambitions would end up destroying anyone who loved her.

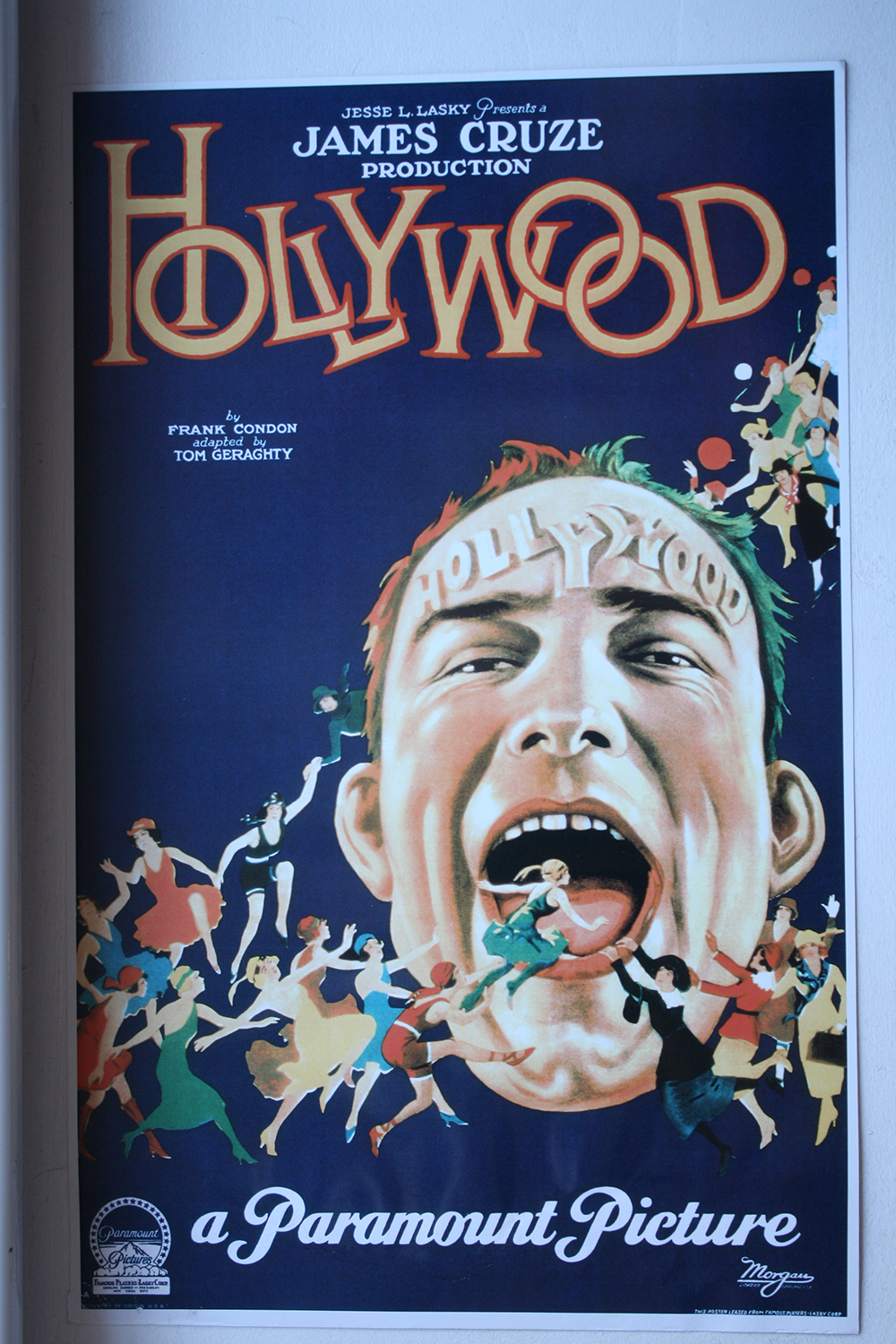

But the 1923 film Hollywood was the first movie to point the way toward this subgenre. [5] The poster that advertised the movie depicts the film industry as a great male maw into which all kinds of fashionably clad women gaily jump. (figure 2) The film’s heroine, Angela, travels from the Midwest to Los Angeles with her grandfather in search of her fame and fortune. In the end, gramps becomes a star while little Angela succeeds only in finding a man to wed. As Angela and her grandfather wander Paramount studio’s new sets, they encounter dozens of kindly, glamorous stars who appear in cameo roles, including Mary Pickford, Pola Negri, Charlie Chaplin, and the slapstick star comedian, Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle. In Hollywood, Angela remains safe – to herself and others – by recognizing that her dreams are foolish and deciding to settle down instead. Go West, Young Women! ends here – with a discussion of this movie and a few other key texts. These vied to explain the American film industry’s relationship to the so-called revolution in manners and morals of the modern American girl that was said to have erupted after World War I ended in 1918. [6]

Hollywood responded to the furor that the American film industry’s first so-called canonical sex scandal – the ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle scandal – channelled about the movie industry’s role in promoting cultural change, particularly among young women. [7] The film directly connected itself to the scandal’s circumstances by featuring a shot of Arbuckle sitting outside Paramount’s casting office, forever waiting a part. This was, of course, the fate Arbuckle experienced after the scandal led William Hays, the first president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association (MPPDA), to ban him from acting in the movies.

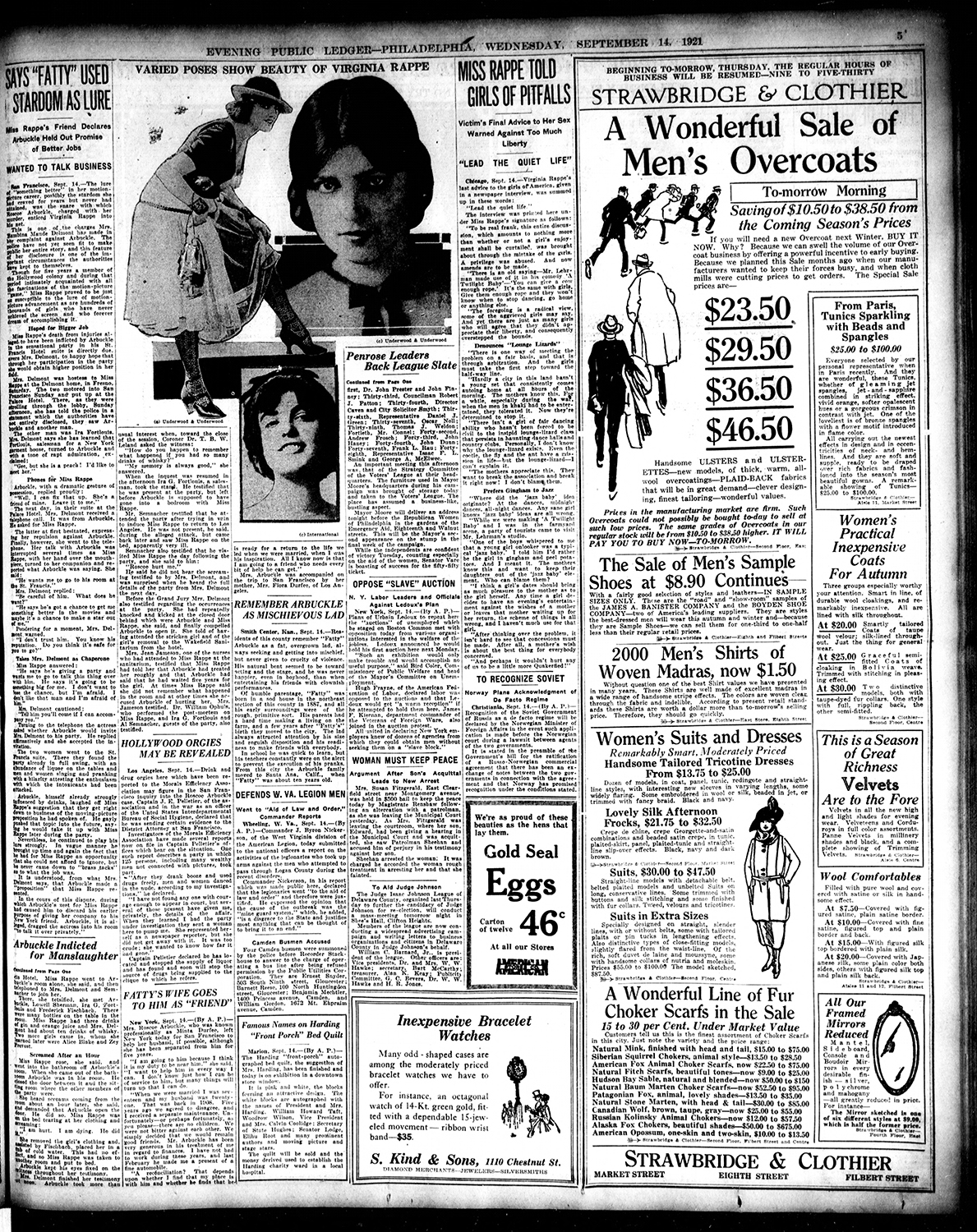

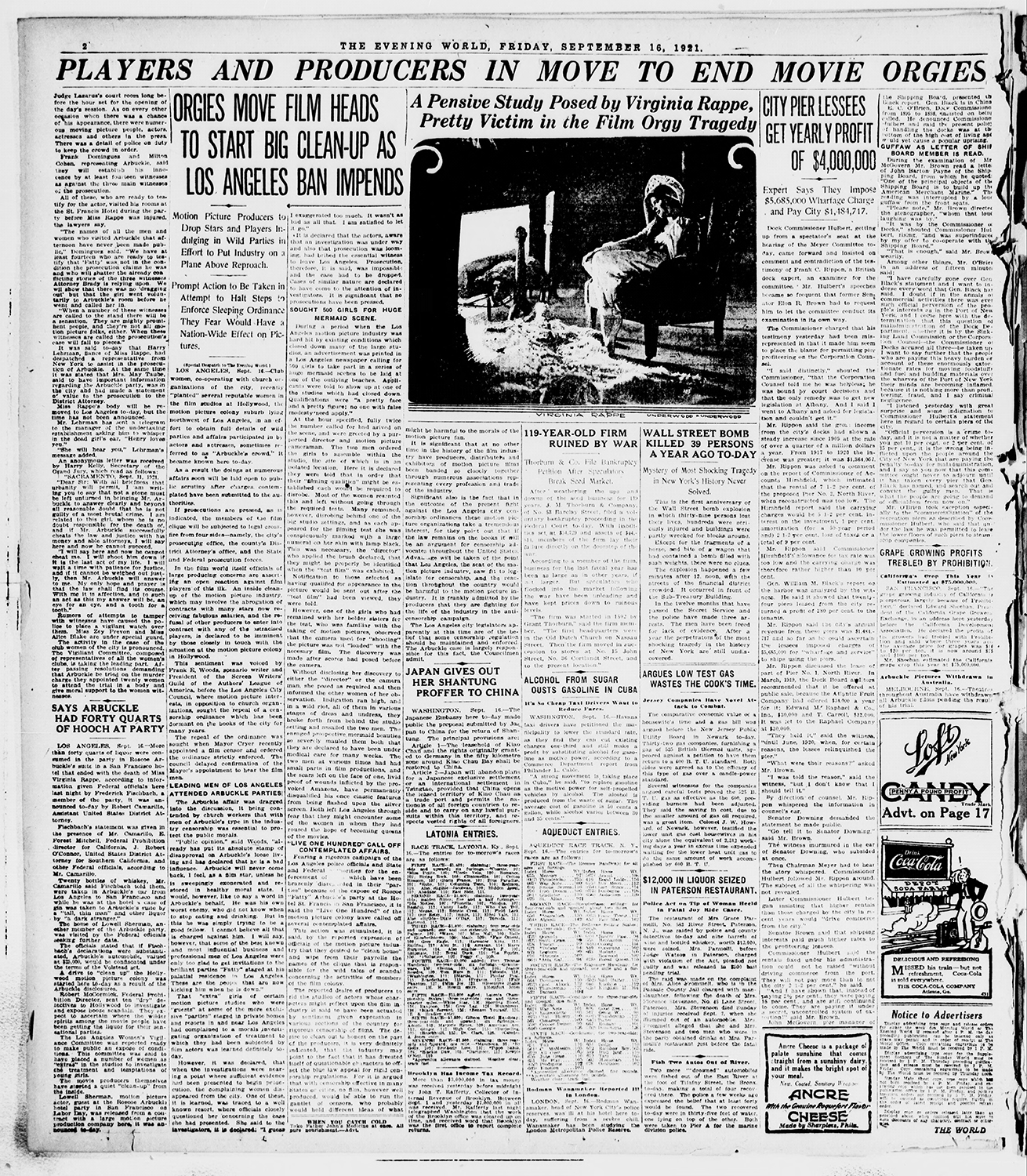

A boilerplate of the so-called Arbuckle scandal is necessary to understand the significance of how most have used the event to offer a particular view of women’s relationship to early Hollywood. A slapstick comedic star, Arbuckle threw a small party with a couple of friends in their suite at the hotel St. Francis in San Francisco on Labor Day, 1921. There was dancing and much drinking despite Prohibition. During the party an actress, or “starlet” as she’s often called, named Virginia Rappe disappeared for a time into one of the suite’s bedrooms with Arbuckle where she became violently ill. Four days later Rappe died of peritonitis, resulting from a ruptured bladder. A female guest told police that Rappe had blamed Arbuckle for her condition before she died. The San Francisco district attorney accused the comedian of murder. A media frenzy erupted in which even typically staid papers like The New York Times ran headlines based on hearsay that shrieked: “Arbuckle Dragged Rappe Girl to Room, woman testifies.” [8] In the months that followed, thirty-two state legislators introduced nearly one hundred new censorship bills to control motion pictures. This was in addition to the more than one hundred and twenty-five censorship bills already under consideration in thirty-six states. Charged with manslaughter, Arbuckle’s first jury deadlocked in December 1921. This convinced the largest American picture producers to create the MPPDA – called the Hays Office for its first and long-time president, William Hays. [9] Hays was the former chairman of the Republican National Committee whom Warren Harding had recently appointed to the position of Postmaster General for his successful efforts in running his presidential campaign. [10] An expert in the new field of public relations, industry leaders hoped Hays would stabilise the industry’s financial, political, and moral capital. The jury at Arbuckle’s third trial acquitted the star in May 1922 and issued an apology. In the scandal’s wake, Hays banned Arbuckle from the screen. He also instituted a morality clause in actors’ contracts that would punish those who did “anything to shock the community or outrage public morals or decency” with immediate termination. [11]

But this emphasis on what happened after the scandal in most accounts – the creation of the MPPDA and the hire of William Hays – has concealed as much as it revealed about what made the Arbuckle publicity and trials so scandalous at the time. [12] The Arbuckle scandal has offered a powerful origins text about Hollywood that has had tremendous influence on establishing a particular view of women’s place in the early American film industry. Scholars, journalists, television writers, and popular historians have all returned to the scandal again and again – and for some good reasons. The scandal first circulated the word “Hollywood” to a broad audience as a term that symbolized both the film industry and a morally unconventional approach to life. [13] Yet what most have missed is how over the course of the scandal Hollywood became shorthand to encapsulate pre-existing fears about the film industry’s influence on modern American culture, and particularly on its so-called modern young girls. Reporting on the event at the time revealed this particular outcome by focusing as much on Virginia Rappe as Arbuckle. The fixation upon Rappe allowed the press to use the scandal to inflame pre-existing fears about how Hollywood had come to infect her – and by extension many other young women – with fearsome new ideas about their social and sexual emancipation. Ultimately, the version of the scandal that won out cast Rappe in one of two negative parts: as a degraded fallen woman or as a career girl with dangerous ambitions. In either case, Hollywood starred opposite Rappe as the villain who had tempted her down the wrong path. Standing in as modernity’s scapegoat, Hollywood came to represent the most corrupting of forces that had encouraged too many of the nation’s daughters to stray too far from home (see figures 3 and 4).

The press expounded this story to the public before Arbuckle’s first jury ever issued a verdict. Weeks after Rappe’s death, the Literary Digest, a popular middlebrow, mainstream weekly periodical, declared, “What the demand for censorship has been unable to accomplish…the revelations of the Arbuckle case most thoroughly accomplished.” [14] The cartoon that accompanied the article succinctly communicated what a “clean-up” of “movie morals” entailed. In the foreground a matronly “ma” confided, “Oh, pa, Tilly has given up wanting to be a movie star” while her daughter, tucked in the kitchen, lightens washing a load of dishes by singing a song. This narrative about the scandal made its way into film scholarship through a series of popular biographies interested in clearing Arbuckle’s name. [15] These books took the character assassination that Arbuckle’s defense attorney performed of Virgina Rappe at his third trial for fact. With only this picture as evidence, Rappe has been repeatedly cast as at best a pathetic starlet or “extra-girl” in early Hollywood melodrama or, at worst, as a two-bit prostitute whose venereal disease caused her death in a Hollywood femme noir.

But the press initially presented Rappe in a much more positive light. Newspapers in early September 1921 almost uniformly described her as a plucky young woman who had followed her ambitions west from her hometown of Chicago and achieved some success in Los Angeles. Early accounts almost uniformly included a drawing from a 1913 Chicago newspaper story about Rappe to support this story in which she advised her “working sisters” to “Be Original—and Grow Rich.” [16]

Go West! emerged from a desire to understand these contradictory presentations of Rappe and to take seriously what young women like her hoped for when they moved west to work in Los Angeles. I learned that Rappe had been a successful model in Chicago before deciding to follow the film industry west to Los Angeles in 1915. In her first few years on the West Coast, she appeared in mostly small roles, at times alongside future stars like Rudolph Valentino. In 1917, she won a more substantial role in the film Paradise Garden, playing a temptress who almost succeeds in luring the rich and handsome hero into succumbing to a life of decadent fun (figure 5). [17] Tracing Rappe’s real life proved hard. Most of the evidence about her came from newspapers and periodicals, and these stories quickly struck me as newsworthy in their own right. The enormous publicity engine that produced the film industry’s first celebrity culture during the 1910s created a strikingly feminized terrain. [18] Even more dramatically, much of this fan culture depicted the industry, and its new home in Los Angeles as well, as a frontier wide open to women. Put differently, the fan culture that helped to produce Hollywood dramatised the promises and perils associated with the new social freedoms and work opportunities opening up to young women in these years. Rappe’s move to Los Angeles in 1915 would have been a logical response to a popular subgenre within fan culture that boosted the industry’s new home in Los Angeles as the ideal environment for women to work and live. An alleged interview with the serial queen Pearl White, in Photoplay in 1920, gives a flavour of these reports.

The early years of the twentieth century brought to American women the same vast, almost fabulous chances that came to their grandfathers … What the expansion of the West and the great organization of industry opened up to many a young man, the motion picture spread before such young girls as were alert enough, and husky enough, and apt enough to take advantage of it. [19]

This hopeful picture of women’s work opportunities in the silent film industry was not just the stuff of dreams, particularly given the industry’s new location in California. In the 1910s, the protections, prerogatives and professional opportunities that California offered women workers, particularly those who were white, surpassed those in other states and regions in America. Young single men swarmed the rest of the Pacific Coast in search of riches in sex-restricted occupations like railroad construction, mining and lumber. But Los Angeles’s economic base of real estate, tourism, and motion pictures created the kinds of service and clerical jobs that attracted women. Women in the state more generally benefitted from California’s early passage of woman suffrage, jury service, and legislation of the eight-hour day in 1911, as well as a minimum wage law in 1917. [20] Gender stratification and racial discrimination in the state remained widespread, but white women experienced less social stratification and greater legislative protections than in most other cities in the United States. In all these ways, Los Angeles best reflected the direction of twentieth-century urban development. For this urban frontier attracted young women out for economic opportunity and excitement.

Actress-writer-producer Mary Pickford was one of the most popular examples used to demonstrate what an ambitious young woman could achieve in this new American West. Readers of Photoplay, which began publishing in Chicago in 1912 and quickly became the wittiest and most popular fan magazine, ranked Pickford first in popularity for fifteen out of the next twenty years. [21] By the time Pickford helped to incorporate United Artists in 1920, her persona was composed of equal parts “America’s Sweetheart” – a romantic spirited ingénue who politely called for women’s rights – and “Bank of America’s Sweetheart,” as her colleague and competitor Charles Chaplin called her. Chaplin’s nickname displayed Pickford’s role as a shrewd businesswomen who became for a time the highest paid woman in the world. [22] A 1922 publicity shot of Pickford beautifully illustrates the two sides of her persona by showing motion picture magnate Pickford in her library keeping up with the news about “Little Mary” (figure 6).

No single writer in the early American film industry did more to explain the significance of stars like Pickford to fans than the journalist Louella Parsons. Between 1915 and 1920, Parsons was among the first and most successful reporters to write a nationally syndicated daily column that offered readers a ‘behind the scenes’ look at the industry’s workers. And Parsons earned her unrivalled following by spinning new western myths about the glorious fate that awaited the female pioneers who followed their heroines to Los Angeles. [23] The prevalence of women reporters like Parsons was connected to the feminization of movie-going during the 1910s. The industry’s preoccupation with attracting female fans helped to explain the prominence of women writers in the periodicals and newspaper columns that composed the industry’s burgeoning fan culture. The strategy of using women writers to appeal to other women was just one of multiple tactics that succeeded in drawing more women into movie audiences. In 1910 women were estimated to compose at best a third of motion picture audiences. But by the early 1920s, when Hollywood’s first star system was in full force, many estimated that they occupied 75 per cent of the seats. [24] While the reality of such statistics is debatable, what is beyond dispute was that at the time most believed they were real.

As a result, after World War I industry insiders imagined their ideal spectator as a youngish white woman – better known at the time as the “flapper fan” – who was eager to identify with role models who reflected the changed conditions under which they worked and played and dreamed. [25] The rise of Hollywood provided ordinary young women with some of the most arresting examples of women who did just that. It is crucial to recall that the development of the American film industry coincided with young women’s soaring participation in public life. This happened for several reasons, including the vibrant women’s suffrage movement that finally won women the right to vote in 1919, and women’s growing participation as patrons of commercial entertainment industries more generally. [26] Women’s increased wage work outside of other women’s homes also drove their new visibility and mobility. The 1920 census, after all, revealed that domestic service was no longer the most common occupation for women. [27]

Louella Parsons was one of these new female workers (figure 7). When Parsons started working as a syndicated motion picture columnist in Chicago in 1915, the movie industry had already effected the near magical transformation in her own life that she came to specialize in selling to fans. A divorce sent Parsons and her young daughter to Chicago in 1910 where she worked as a secretary at a newspaper. Within two years she had become a scenario editor at the Chicago film studio Essanay. By 1915, she had published How to Write for the Movies. [28] The book was a hit and Parsons sold the serialization rights to the Chicago Herald Record where she became one of the first nationally syndicated motion picture columnists. The column Parsons wrote partially presented the movies in ways that prefigured how Hollywood’s star system helped to spread the consumer ethos that exploded during the 1920s. Her coffee-klatch style suited the needs of expanding corporate media structures that sought to preserve an intimate tone despite their scale. As a late-Victorian woman from the countryside turned working professional single mother in the city, Parsons was ideally suited to address the broad target audience coveted by consumer culture: a cross-class, multi-generational audience of white women with a modicum of disposable cash. According to the advertising journal Printers’ Ink, all these women led “monotonous and humdrum lives” and craved “glamour and color.” Parsons’ column partially presented the industry as designed to fill these needs. [29]

Yet in ways that pointed to Hollywood’s Janus-faced relationship to modern femininity, the fan culture of the movies also treated fans as intimates in a conversation about the pleasures and perils of embracing an individually oriented and desire-driven type of womanhood. [30] One of Parsons’ first special Sunday series – “How to Become a Movie Actress” – aimed to induce a self-reflective reverie in female readers that encouraged them to take their daydreams about pursuing an independent adventure to heart. [31] Its opening prelude whispered, “Dreams – dreams most fascinating to young women all over America are coming true everyday.” [32] Parsons, and those she interviewed, treated the ambition to work in the motion pictures with matter-of-fact aplomb, contradicting the notion that such desires were fabulous at all. Indeed, in Parsons’ hands, this became one of the central products that the film industry sold to fans: romantic coming-of-age adventure stories for girls interested in seizing new work opportunities and cultural freedoms that promised happy-ever-after endings.

Written by, for, and about women, these stories framed the topic of women’s experiences in this New American West in the context of what other women wanted to hear in an era in which the New Woman, feminism, and women’s influence on popular culture were all topics of lively social controversy. In contributing to such discussions, the fan culture that surrounded Hollywood’s rise advertised its workers as what I call ‘new western women.’ [33] Hollywood’s new western women offered a visible sign of modernity as glamorous, individualized, and work-defined personalities known for breaking and reassembling many of the codes governing feminine propriety on and off screen. The appeal of these mass-produced narratives about the industry’s female personalities encouraged many women to seek work in some aspect of the picture business. And their movement to Los Angeles eventually made female migrants a particularly visible stream in the massive migration of mostly native born, Midwesterners of Anglo-Saxon descent who made Southern California the nation’s fastest growing region by World War I. [34]

Considered little more than a dusty backwater in 1910, by 1920 Los Angeles was known as the film capital of the world and the nation’s fifth largest city. [35] Charting the industry’s resettlement in Los Angeles also left Parsons ideally positioned to explain to readers what this new environment promised women. A story about one scenario writer’s decision to move from New York to Los Angeles in 1920 found Parsons resurrecting Horace Greeley’s old advice for feminist ends. “When Horace Greeley penned those immortal words, ‘Go West, Young Man,’ he failed to reckon with the feminine contingent. That of course was before the days of feminism,” Parsons wrote. “In the good old days when Horace philosophized over the possibilities in the golden west he thought the only interest the fair sex could have in this faraway country was to go as helpmate to a man. But that was in the good old days,” Parsons dismissed. “In the present day, if milady goes west she travels not to sew on buttons or do the family washing, she goeth to make her own fortune,” she concluded, in advice that inspired the title for my book. [36]

By breezily describing Los Angeles as an urban El Dorado for intrepid female migrants, the fan culture surrounding Hollywood’s rise sparked the migration of tens of thousands of single white women – white here standing for the ethnic identity then commonly called Anglo-Saxon – to the region each year by the nineteen-teens. “There are more women in Los Angeles than any other city in the world and it’s the movies that bring them,” was how one shopkeeper described the relationship. [37] The demographics of Los Angeles supported the observation. By 1920, the city was the only western boomtown in which women outnumbered men. Moreover, an astonishingly high percentage of these women were either single or divorced and thus not part of the family unit that typically characterised most women’s migration experience to the American west. This also contributed to what one demographer called Los Angeles’s most unusual characteristic in 1920: the unusually large number of women who worked for wages over the age of twenty-five. [38]

In the context of her day, Parsons’ reporting placed her among those who first called themselves feminists. [39] The radical suffragist Alice Paul later made the term virtually synonymous with the activities of the National Woman’s Party by the late twenties, but feminism initially resisted definition. In 1913 Harper’s Weekly called feminism “of interest to everyone,” reflecting “the stir of new life, the palpable awakening of consciousness.” The Missouri Anti-Suffrage League explained in 1918 that “Feminism advocates non-motherhood, free love, easy divorce, economic independence for all women, and other demoralizing and destructive theories.” [40] And, indeed, feminists sought to call into question the whole architecture of customs surrounding sex roles and the meanings attached to sexual difference. This meant that many of the period’s women’s rights activists avoided the label for fear that its connection to women’s broader cultural and sexual freedoms would endanger winning the vote.

After the war, a wave of more sexually risqué films and personalities intensified the perception that Hollywood promoted a feminist sensibility by fomenting the breakdown of the sexual double standard and spreading new customs later associated with what got called “companionate marriage.” [41] Foreign movies and personalities like Pola Negri, Rudolph Valentino, Elinor Glyn, and Alla Nazimova displayed how behavior associated with European artists helped to licence Hollywood’s projection of gender roles and sexual mores that appeared startlingly new to many. These films and personalities helped Hollywood to stake out a position as an international fashion trendsetter by wedding conventions associated with pre-war working girls to continental glamour and Oriental exoticism. In the process, they created the particular brand of glamour associated with Hollywood’s post World War I rise.

The persona of Gloria Swanson, the screen’s first so-called Glamour Queen, was the American actress who best embodied the postwar shift toward using an orientalised, European glamour to present a more sexually sophisticated image of who the post-war flapper fan might grow-up to become (figure 8). Swanson rose to stardom in six so-called “marriage and divorce pictures,” or “sex pictures,” that Cecil B. DeMille directed between 1919 and 1921. “She looked like she knew what life was all about, and in those days that was a sin for which you could be burned as a witch,” one contemporary reviewer wrote of her effect in these films. [42] In using glamour to smooth the presentation of her unconventional persona, Swanson mobilised what historian Peter Bailey calls “a distinctly modern visual property.” Glamour helped to account for how consumer capitalism disseminated and normalized new sexual roles and norms by marketing a “middle ground of sexuality.” An “open yet licit” form of eroticism, glamour was “deployed but contained, carefully channelled rather than fully discharged.” [43] The approach helped to explain why images of female bodies – and of male ones like Rudolph Valentino’s – proliferated so rapidly along with Hollywood’s rise to become an acceptable if contested feature of modern public life.

Swanson’s glamorous image set new trends by wrapping her adult sensuality in a cosmopolitan, non-Anglo-Saxon package. The first to forgo the rage for tiny Cupid’s bow lips, she “emphasized the generous outline” of her mouth and wore “her straight dark hair” around “her head, turban fashion.” [44] Synonymous with neither beauty nor sex, glamour’s provenance lay in poetry, in an allure fashioned from mystery, magic, and contrivance. [45] Never considered a great beauty in her day, Swanson’s famed “ability to wear clothes” indicated glamour’s creation through the expert manipulation of externals. Her fashion choices associated her with the famed sensuality both of the French – or what was becoming a more general Latin brand – and of the Far East. Distance – in Swanson’s case, both the objective absence created by her mechanically reproduced image and the subjective remove fashioned by her aloof persona – was central to the exercise of glamour. This allowed Swanson’s persona to speak to fans of their sexual power rather than their sexual exploitation by communicating their desires without sacrificing their self-respect.

After the war, keen observers of the movie colony increasingly described not just Glamour Queen Swanson, but also the industry’s more ordinary workers as inhabiting that quintessential modern metropolitan neighbourhood of glamorous self-reinvention: a bohemia, a Hollywood-Bohemia to be exact. [46] The regular references by the mid-teens to Los Angeles’s so-called movie “colony” anticipated the emergence of Hollywood’s identity as a bohemian third space, someplace “on the edge of town,” on the “margins,” where “clannish” and “outlandish” customs set the trends desired and criticised by others in equal measure. [47] The image of a shape-shifting, cosmopolitan city-within-a-city keyed to self-reinvention set the stage for the development of the Hollywood Bohemia social imaginary that appeared after the war as Los Angeles shot to become one of the nation’s largest cities and motion pictures became California’s most lucrative industry.

Calling the movie colony a bohemia may sound as strange today as it did when the article “Oh, Hollywood! A Ramble in Bohemia” appeared in Photoplay in 1921. This “Greenwich Village in the West,” it admitted, “was not so much exploited or propagandized, but pack[ed] the same wallop in each hand.” [48] To be fair, viewing Los Angeles as a bohemia is hard to see. The city’s sprawling, sunny suburban terrain violates the idea of a proper bohemian space. The movies’ crassly commercialized product has also long made it easy for many cultural elites to discount the artistry and artists involved in moviemaking and, therefore, the industry’s bohemian image. The problem relates to the long-standing tendency of the city’s educated, Anglo elite to dismiss the influence of the “flickers” and their “movies” – as many called the early industry’s workers and product – on the city. In the popular mind, Hollywood has held a near obliterating influence on the development of the city’s economy and reputation. But the idea that Los Angeles was too controlled by conservative, recently transplanted Anglo Midwesterners to nurture anything but conformity was a commonplace in early descriptions of Los Angeles. [49] Indeed, most historians of Southern California continue to ignore the film industry’s role in the region’s growth and development despite the fact that motion pictures had become California’s largest industry by 1922. This likely explains the failure to examine the unusual gender dynamics that characterised Los Angeles during the era of Hollywood’s rise.

Without a doubt, Hollywood-Bohemia was always in part a marketing tactic that conveyed the more sexually sophisticated, European-flavored glamour that the industry sold after the war. The promotion aimed to sell the movies as much as to challenge the sex roles, work ethic, and social norms of the respectable middle class. But this tension – between the wish to market goods through their association with a life of exotic, liberated fantasy, and the desire to carve out spaces on the margins to enact genuine rebellions against middle-class norms – has always lain at bohemia’s heart. [50] Bohemia housed the archetypical artist – freed or bereft of patrons, depending on one’s point of view, and forced to the market – whose success represented the triumph of talent over circumstance that bourgeois society valorized. Hollywood Bohemia promoted this image of its residents. But as a social phenomenon, it offered both a place and an imaginary space where the young could challenge the hypocrisies and limitations of the conventions associated with middle class life. Hollywood’s bohemian new west built on American modifications that already incorporated women as artists and lovers, as well as muses and mistresses. Greenwich Village’s bohemians first modified its once hyper-masculine scene, recasting sex roles so women might play more active parts. [51] But since most female artists in the village had failed to find stable means of self-sufficiency, old sex roles often reasserted themselves especially after marriage and if children appeared. In contrast, the greater professional success of women working in the film industry sustained their greater public influence. Moreover, the comparatively high wages paid both to extras – people who worked mostly in bit parts on sets – and to women workers in more typical pink-collar jobs in Los Angeles meant that most earned a living wage during the silent era. [52]

A Hollywood secretary named Valeria Belletti displayed the personal transformations wrought by embracing a bohemian spirit envisioned as a healthful, beautifying adventure enjoyed equally by women and men. A former secretary at a talent agency in New York, Beletti moved to Los Angeles alone at the age of twenty-five. Beletti’s letters back East displayed her embrace of the bohemian commitment to passion, pleasure, and self-actualisation through work. After describing her participation in Los Angeles’s bohemian scene, Beletti wrote how she had come to realise that she hadn’t been “living her own life” back East “due to some sense of duty.” But “Now I’m much happier,” she declared, “and I am fitting myself to do the thing that I desire most – and that is to write. I don’t know if I’ll ever amount to anything, but…I want to write because that is the thing which will give me the most pleasure.” [53]

By the war years, cultural commentators fastened on the unusual prominence of all kinds of women workers in Los Angeles. But reports particularly focused on the number of single working young women within the bohemian movie colony who appeared to live happily like bachelors in western boomtowns of yore. And increasingly the figure of so-called extra girls like Virginia Rappe best captured the mounting fears that Hollywood’s rise provoked inside in the United States. “Hollywood: A Ramble in Bohemia,” was also the first feature in Photoplay to use the term Hollywood to stand in for the movie colony’s social scene as a whole. The conjunction indicated how the terms bohemia and extra girl were co-dependent in the industry’s first social imaginary. [54] Published a few months before the Rappe-Arbuckle scandal erupted, the article claimed that what distinguished Hollywood’s bohemia was how its girls were equal partners in rebellion with the boys. “Women can – and do – what they like,” the article explained for “they work, play, love and draw their pay checks on exactly the same basis as men.”

Such reports led mainstream reporting to hold the film industry responsible for inciting the breakdown of the sexual double standard that was the most dramatic manifestation of the revolution in manners and morals after the war. On the defensive, some industry insiders argued that the moral character of female migrants determined their fate. As one producer admitted, too many “colorful stories” sent “an army of girls to Los Angeles every year.” Those with “‘Bohemian’ bacillus” in their systems ended up in “a store,” “a restaurant,” or the “morgue.” This led the producer to conclude: “The movies need the nice girl … and when you do go, take your mother or auntie with you – and live with her.” [55]

After the Rappe-Arbuckle scandal, Hollywood had to find a more equivocal register to whisper to women of its bohemian pleasures. In the 1920s, celebrity culture abandoned spinning such unabashedly romantic adventure stories about the glories awaiting the ambitious female migrants who went west to make their fortunes, and to remake themselves, along Hollywood’s streets. Yet during the 1920s Hollywood’s publicity still continued to communicate a sense of opportunity to ambitious women around the world. The task became harder after 1934, when movie producers buckled under the combined pressure of the Depression and the moral outrage that stars like Mae West prompted in the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. [56] The new version of the Motion Picture Production Code that the devoutly Catholic Joseph Breen enforced made regulating women’s independence and enforcing the sexual double standard their particular obsessions. [57] Increasingly, stories about adventurous, ambitious, single women like Virginia Rappe in Los Angeles were set in a Hollywood femme noir frame that left them dead on the side of the road. This trajectory reminds us that women’s so-called liberation in the twentieth century “West” more generally has taken a crooked path marked by limitations at every step.

But as the twentieth century recedes, returning to the women who drove Hollywood’s rise in America’s new west emphasises one of the most striking aspects of the century’s arc: the expansion of women’s opportunities in consumer-oriented, democratic societies – which is nowhere more visible in the United States than in California, where women exercise unparalleled clout in both politics and culture. To understand this process, Hollywood’s relationship to feminism and modern femininity demands another account. In its heyday, through World War II, Hollywood perfected talking to women from at least two directions, providing them with stars and stories that played to their New Women ambitions, while ridiculing these aspirations and radically constricting their professional opportunities. Yet, even after World War II, during the so-called “doldrums” of the feminist movement, actresses like Barbara Stanwyck offered rare avatars of “The Independent Woman” that Simone de Beauvoir discussed in The Second Sex. [58]

Female fans’ “heroine worship” of early Hollywood’s New Western Women then reflected the desire of many modern young girls to embrace a type of individually oriented, “feminine friendly” feminism. Compatible both with capitalism and with popular culture, this feminism provides continuity with many of the preoccupations of what some call third-wave feminism today, which is typically thought of as focusing on women’s empowerment rather than their victimisation and as taking pleasure in fashion, romance, and sex. During the era of the silent screen, this approach was more likely to be embraced by working-class secretaries than college graduates. It appealed mostly to young, single, divorced, or self-styled bohemian women rather than middle-aged wives or more respectable middle-class professionals. It focused on the problem of women’s individuality rather than their group identity. It celebrated women’s ability to seize prerogatives long enjoyed by single young men while cultivating their boy-crazy day-dreams and use of a glamorously “femme” façade as a reasonable means to get ahead. In short, it assumed that, more than a political movement, women needed role models like Hollywood’s New Western Women who could teach them how to navigate modernity’s choppy waters – and come out on top.

Endnotes

[1] Hilary A. Hallett, Go West, Young Women! The Rise of Early Hollywood (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

[2] Sumiko Higashi, “The New Woman and Consumer Culture,” in Jennifer M. Bean and Diane Negra, A Feminist Reader in Early Cinema (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 302.

[3] What Price Hollywood? (George Cukor, RKO Pathe, 1932).

[4] Adela Rogers St. Johns, The Honeycomb (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969), 97.

[5] Hollywood (James Cruze, Paramount, 1923).

[6] The term was coined in, Fredrick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s (New York: Harper & Row, 1931), ch. 5, “The Revolution in Manners and Morals.” Scholars largely followed Allen’s lead in emphasising dramatic post-war cultural changes visible among young middle class women until the critique offered by Estelle Freedman in “The New Woman: Changing Views of Women in the 1920s,” Journal of American History 61 (1974): 372–393. Freedman argued that too much emphasis had been placed on cultural freedoms among this set at the expense of evaluating women’s continued political involvement.

[7] For more details on the scandal, see Hallett, Go West, Young Women, ch. 5, “A Star Is Born: Rereading the ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle Scandal.”

[8] “Arbuckle Dragged Rappe Girl to Room, Woman Testifies,” New York Times, Sept. 12, 1921, p. 1.

[9] After complete silence during the scandal, Arbuckle’s acquittal found Photoplay editorials expressing such hopes: see April, 1922, “Moral House-Cleaning in Hollywood: A Straight from the Shoulder Talk, and Open Letter to Mr. Hays,” and May, 1922, “Will Hays – A Real Leader; A Close-Up of the General Director of the Motion Picture Industry.” On the background of Hays, see Gregory Black, Hollywood Censored (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 30-32.

[10] On Hays’s role in Harding’s election, see Ellis Hawley, The Great War and the Search for Modern Order (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992), 44–49; Michael McGerr, The Decline of Popular Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 169–171; John Braeman, “American Politics in the Age of Normalcy,” 17–18, in John Earl Haynes, ed., Calvin Coolidge and the Coolidge Era (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1998).

[11] “Morality Clause for Films,” New York Times, Sept. 22, 1921, p. 8; “Morality Test for Film Folk,” San Francisco Examiner, Sept. 22, 1921, p. 2.

[12] See for instance, Larry May, Screening out the Past (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 179, 204-5; Robert Sklar, Movie-Made America (New York: Vintage, 1976), 82-88; Black, Hollywood Censored, 29-33; Frank Walsh, Sin and Censorship (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), 24-26; Richard deCordova, Picture Personalities (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990), 131-132. These books in part follow the template laid down by the account of the journalist and pioneering film historian Terry Ramsaye, A Million and One Nights (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1926), 803-821.

[13] “Hollywood” as a term suggesting the film industry first appeared in the Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature (Minneapolis: H.W. Wilson Co.) with “In the Capital of Movie-Land,” Literary Digest (Nov. 10, 1917): 82–89. The term appeared regularly only after 1922. Similarly, in ProQuest Historical Newspapers, “Hollywood” was first used to mean something more than a location in “Hollywood Is Interested,” Atlanta Constitution, July 3, 1921, p. F3. The usage proliferated during 1922 after its use in reports on the scandal.

[14] “Time to Clean Up the Movies,” Literary Digest (Oct. 15, 1921): 28–29.

[15] The first biography interested in clearing the comedian’s name was David Yallop, The Day the Laughter Stopped (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1976). Yallop claims to have obtained copies of the trials’ transcripts. In comparing his text to one of the trial transcripts in my possession, I found that he misrepresents some of the statements made in court. Two other popular biographies display similar tendencies: Andy Edmonds, Frame Up! The Untold Story of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle (New York: William Morrow, 1991); Stuart Oderman, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1994). All three basically follow Arbuckle’s defense attorney, Gavin McNab’s characterisation of Rappe.

[16] “Chicago Best City For Girls,” Chicago Evening American, Jan., 3, 1913, 3.

[17] Paradise Garden (Fred J. Balshofer, Metro, 1917).

[18] On the reorientation of fan magazines toward women readers which resulted in the feminization of movie fan culture, see for instance, Benjamin Hampton, A History of the Movies, from its Beginnings to 1931 (New York: Dover, 1970 [1931]), 224–226; Leo Rosten, Hollywood: The Movie Colony, the Movie Makers (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1941), 12–15, appendix H, “Fan Mail”; Gaylyn Studlar, “The Perils of Pleasure? Fan Magazine Discourse as Women’s Commodified Culture in the 1920s,” Wide Angle 13 (Jan. 1991): 6–33; Miriam Hansen, Babel and Babylon, Spectatorship in American Silent Film (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991) 245–268; Kathryn Fuller, At the Picture Show: Small-Town Audiences and the Creation of Movie Fan Culture (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996); Melvyn Stokes, “The Female Audience of the 1920s and Early 1930s,” in Stokes and Richard Maltby, eds., Identifying Hollywood’s Audiences: Cultural Identity and the Movies (London: British Film Institute, 1999), 42–60; Shelley Stamp, Movie-Struck Girls: Women and Motion Picture Culture after the Nickelodeon (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 10–40; Richard Abel, “Fan Discourse in the Heartland: The Early 1910s,” Film History 18 (2006): 146.

[19] Julian Johnson, “The Girl on the Cover,” Photoplay (April 1919): 57–58.

[20] Rebecca J. Mead, “‘Let the Women Get Their Wages as Men Do’: Trade Union Women and the Legislated Minimum Wage in California,” Pacific Historical Review, 67 (1998), 317–347, and Mead, How the Vote Was Won: Woman Suffrage in the Western United States, 1868–1914 (New York: NYU Press, 2004).

[21] Jeanine Basinger, Silent Stars (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2000 [1999]; distr. by University Press of New England), 18.

[22] Charles Chaplin, My Autobiography (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1964), 222. On the centrality of her salary and business negotiations to her persona, see Mary Pickford Core Clipping File, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Los Angeles (hereafter, PCC, MHL); Sumiko Higashi, “Million Dollar Mary,” in Virgins, Vamps, and Flappers (Montreal: Eden Press, 1978).

[23] For more detail on Parsons’ reporting in this vein, see Hallett, Go West, Young Women! ch.2, “Women Made Women.” On Parsons more generally, see Samantha Barbas, The First Lady of Hollywood (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

[24] Photoplay (Nov. 1924), quoted in Studlar, “Perils of Pleasure?” 7.

[25] Herbert Howe, “Is Mary Pickford Finished?” The Preview, March 25, 1924, pp. 7–11, PCC, MHL.

[26] Mead, How the Vote Was Won. On the suffrage movement’s use of actresses as glamorous front women, see Albert Auster, Actresses and Suffragists: Women in the American Theater, 1890–1920 (New York: Praeger, 1984); Ellen Carol DuBois, Harriet Stanton Blatch and the Winning of Woman Suffrage (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997); Margaret Finnegan, Selling Suffrage: Consumer Culture and Votes for Women (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999). On how commercial entertainment supported young women’s participation in public life more generally, see. Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn of the Century New York (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986); Nan Enstad, Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure: Working Women, Popular Culture, and Labor Culture at the Turn of the Twentieth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999).

[27] On the shift in women’s wage-earning in the early twentieth century, see Alice Kessler-Harris, Out To Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States (New York: Oxford, 1982), ch.5.

[28] Louella O. Parsons, How to Write for the Movies (Chicago: A.C. McClurg, 1915). The book was successful enough to be revised and reprinted in 1917.

[29] Quoted in Roland Marchand, Advertising the American Dream (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 67.

[30] On mass culture’s ability to act as ‘intimate public’ for women, see Lauren Berlant, The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of American Sentimentality (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 5-13.

[31] N.d., Parsons Scrapbook no. 1, MHL. The series ran on Sundays for several months in 1915.

[32] “How to Become a Movie Actress,” Sept. 15, 1915, Parsons Scrapbook no. 1, MHL (italics in the original).

[33] For more on this concept, see Hilary A. Hallett, “Based on a True Story: New Western Women and the Birth of Hollywood,” Pacific Historical Review (May 2011): 176-187.

[34] By 1920 the largest nativity group in California was native-born migrants of mid-American origin; see Warren S. Thompson, Growth and Changes in California’s Population, (Los Angeles: Haynes Foundation, 1955), 16–17, 47–51, 53–65. On how women’s unusual migration patterns to Los Angeles made the city’s sex ratio 97.8:100; see Thompson, Growth and Changes, 48–51, 88–89; Frank L. Beach, “The Effects of Westward Movement on California’s Growth and Development, 1900– 1920,” International Migration Review 3 (1969): 25–28.

[35] Kevin Starr, Material Dreams: Southern California through the 1920s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 69, 98.

[36] “In and Out of Focus: Josephine Quirk; She Is Following Horace Greeley’s Advice and Going West,” Nov. 21, 1920, Parsons Scrapbook no. 4, MHL.

[37] Suzette Booth, “Breaking into the Movies,” Motion Picture Magazine, June 1917, p. 76. This was a monthly serial that ran between January and June 1917.

[38] Thompson, Growth and Changes, 89–93, 112–115. On unmarried women’s higher work rates, Joseph Hill, Women in Gainful Occupations, 1870 to 1920; Census Monograph IX (1929; Westport, CT, 1970), 270–276.

[39] I follow Nancy Cott in emphasising the importance of “sex rights,” sexual equality, difference, and variety to feminism; my definition does not emphasise formal political action since this would exclude most women outside the educated middle class and was not originally central to feminism; see Nancy F. Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987), 7–9.

[40] Both quotes from Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism, 190-191.

[41] Ben Lindsey and Wainwright Evans, The Companionate Marriage (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1927).

[42] Howe, “Is Mary Pickford Finished?” The Preview, March 25, 1924, 7–11, PCC, MHL.

[43] Peter Bailey, “The Victorian Barmaid as Cultural Prototype,” in Popular Culture and Performance in the Victorian City (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 156, 151.

[44] Frances Marion, Off with Their Heads! (New York: Macmillan, 1972), 69.

[45] Walter Scott brought the word glamour into English in his poem The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805). When a goblin charged by his master to bring him a particular book of spells finds the volume he opens it to read: “It has much of glamour might/ Could make a ladye seem a knight/ The cobwebs on a dungeon wall/ Seem tapestry in lordly hall/ …And youth seem age, and age seem youth – / All was delusion, nought was truth.”

[46] For more on this development, see Hallett, Go West, Young Women! ch.5, “Hollywood Bohemia.”

[47] “The Jazzy, Money-Mad Spot Where Movies Are Made,” Literary Digest (Mar. 6, 1921): 71; “Chameleon City of the Cinema,” The Strand Magazine quoted in Washington Post, June 20, 1915.

[48] Mary Winship, “Oh, Hollywood! A Ramble in Bohemia,” Photoplay (May 1921): 111.

[49] Willard Huntington Wright, “Los Angeles – The Chemically Pure,” in Burton Rascoe and Groff Conklin, eds., The Smart Set Anthology (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1934 [1913]), 90–102.

[50] The most sensitive chronicler of Bohemia’s origins is Jerrold Seigel, in Bohemian Paris (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999 [1986]).

[51] On Greenwich Village’s innovations, see Christine Stansell, American Moderns (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2000), 225-308. On its past hyper-masculinity, see Seigel, Bohemian Paris, 40-42.

[52] Murray Ross, Stars and Strikes: The Unionization of Hollywood (New York: Columbia University Press, 1941), 70–75, 85–86.

[53] Valeria Belletti to Irma Prina, all in Cari Beauchamp, ed., Adventures of a Hollywood Secretary: Her Private Letters from Inside the Studios of the 1920s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 44–47, 69–70.

[54] Here I have in mind the idea that “the social imaginary . . . is what enables, through making sense of, the practices of society”: Charles Taylor, “Modern Social Imaginaries,” Public Culture 14 (Winter 2002): 90.

[55] “Movie Myths and Facts As Seen By an Insider,” Literary Digest, May 7, 1921, p. 38. Italics in the original.

[56] Black, Hollywood Censored, 29-33. Lea Jacobs, The Wages of Sin: Censorship and the Fallen Woman Film, 1928-1942 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991).

[57] Black, Hollywood Censored, 170-171.

[58] In her ex-post-facto feminist manifesto, de Beauvoir argued that the actress best symbolised the so-called independent woman she discussed in the last chapter of the book. De Beauvoir called actresses nothing less than the “one category” of women whose behaviour pointed the way towards the liberation of their sex, see Simone de Beauvoir, “The Independent Woman,” in The Second Sex (New York: Vintage, 1989 [1949]), 683, 702-723.