Introduction

Interactive cinema (IC) is a productive realm of inquiry in film and media studies. This area of inquiry compels us to rethink the role of film narrative in contexts of national economies, transcultural exchange, and globalization. Despite significant differences in year of release, production, marketing, and mixed media, interactive films use a diverse set of interrelated strategies to differentiate their performances from other kinds of theatrical and domestic viewing experiences. In particular, IC attempts to dismantle the conventions and theories associated with the darkened theater and spectator passivity by integrating elements like live performance, audience voting, and motion sensors to create a participatory, multimedia experience. Such practices are evident in IC endeavors ranging from experimental works (like Radúz Činčera’s Kinoautomat, 1967, which incorporates audience voting to generate a choose-your-own-adventure narrative), to Expanded Cinema (Roman Kroitor’s Labyrinth, 1967, featuring a traversable architectural space for viewers to walk through), to art installations (Lynn Hershman’s Lorna, 1979–83, which lets visitors interact with media to uncover the story of an agoraphobic woman), to popular commercial movies (William Castle’s Mr. Sardonicus, 1961, featuring a punishment poll that decides the villain’s fate at the film’s end).

The study of ICs – ranging from mixed media installations to digital formats – is gradually becoming integrated into contemporary media studies, especially digital studies and new media theory. Since interactivity [1] is, arguably, one of the distinguishing characteristics of new media, it is no wonder IC is being rediscovered within the scope of digital studies, and is becoming associated with the form of database cinema [2] – a cinema that renders transparent the processes of selection and recombination characteristic of digital databases in an arguably similar manner as the selection and recombination processes characteristic of pre-digital ICs. [3] However, what is often neglected in this rediscovery of database narrative’s possible archetypes are the actual narrative aesthetics and reception contexts of these works, which often convey invaluable cultural and social insights. [4] Although some of these works lack substantial records of contemporary viewers’ impressions of the experience, close readings and formal analysis of such works can still provide useful information about their contexts of reception, as well as insight into sociopolitical ideologies driving the use of the interactive format. Such approach problematizes the typical reading of interactivity as a transhistorical, transnational, and digitally defined phenomenon.

While concepts of interactivity are generally bound to mythologies characterized by rhetoric of empowerment and/or user manipulation, I focus on historically, socially, and politically specific sub-discourses associated with interactivity. These particularities enable us to approach interactivity as more than a technologically oriented phenomenon, and – significantly – to understand it outside of the developmental path that leads to (and often ends with) digital media. I expand the concept of discontinuous and variable media(ted) history through rigorous cross-contextual analysis of both undiscovered and pioneering interactive films such as the aforementioned Czechoslovakian film Kinoautomat. This particular film is an early example of Expanded Cinema: it attempted to expand the cinematic space through a live performance component, and to promote an expanded state of consciousness by redefining the role of the spectator to that of an active participant. As a retrospectively acknowledged example of the 1960s Czechoslovakian New Wave, the film and its interactive performance simulated a powerful critique of the elusive notion of democracy in a socialist and communist context.

Transnational or Non-historicized? Can Films Transcend Context?

In many recent interactive films, interactive aspects of the film’s projection and consumption take precedence over otherwise unremarkable narrative or aesthetic content. Cinema 3.0, a phrase coined by Kristen Daly, is identified as “a form of cinema where navigating, intertextual linking, and figuring out the rules of the game provide the primary pleasures.” [5] According to this definition, narrative pleasure is derived chiefly from interactions with cinematic objects; much of that pleasure for viewers lies in the active discovery of narrative(s) instead of narrative comprehension and other conventional modes of spectatorship. In her definition of Cinema 3.0, Daly primarily has in mind examples of Web cinema for which the viewer is also the navigator. Films that demand the viewer to interact intellectually with the story also share attributes she describes; such films fall into the mind-game film category, wherein how the story is told is (at least initially) more important than the story itself. Thomas Elsaesser asserts that, in mind-game films, “the spectator’s own meaning-making activity involves constant retroactive revision, new reality-checks, displacements, and reorganization not only of temporal sequence, but of mental space, and the presumption of a possible switch in cause and effect.” [6]

Mind-game films, like cinema 3.0, are mostly commended for the unusual ways in which they tell stories and engage viewers. Mind-game films such as the paradigmatic Memento (Nolan, 2000) and The Sixth Sense (Shyamalan, 1999) are more remembered for their manipulations of conventional cinematic temporality, cause and effect, and parallel planes of reality, than their derivative plots. Elsaesser goes as far as to suggest that mind-game films transcend national cinema because they raise universally resonant epistemological doubts and ontological concerns. What mind-game and cinema 3.0 films have in common with interactive films that they are all frequently regarded as symptomatic of the role of the moving image in an increasingly networked and digital world; the demands they make on the viewer are consonant with the “new multitasking personality” emerging out of an arguably postmodern or post-human condition. [7]

Therefore, even if these films do not fully cohere causally and temporally within conventions of narrative cinema, historical reception and cultural formations can make accessible, at least on some level, even those films most resistant to interpretative legibility. In the case of interactive films (as well as 3.0 and mind-game films), their debatable reflection of universal sensibilities and conditions makes them relatable or engaging on a human level that is capable of transcending specificities such as national heritage and even gender. However, the contextualization of these filmmaking trends and themes within the evolutionary framework of technological developments can lead to deterministic assumptions about the impact of technology on the aesthetics of cinema and on cultural or global perception at large. Moreover, such interpretations contribute to a limited understanding of contemporary identities, whereby the medial distinction of the digital is used to reconcile variants of human experience and expression, such as social upbringing and phenomenological differences.

Timothy Corrigan suggests that historical and cultural distance can produce new interpretations of films. [8] However, in the case of IC prototypes such as Kinoautomat, it seems that the justification of their contemporary relevance in retrospective analysis actually reveals an ahistorical and depoliticized excavation of these works for the sake of (retroactively) historicizing the roots of digital media. In attempting to place digital media within the broader context of media evolution, purported precursors of these media run the risk of being reductively re-historicized (or miscontextualized) in that they are valued primarily for their relation to new(er)–that is, subsequent–media, and for the way they illuminate current media trends and discourses. Ironically, in trying to provide a broader understanding of new media by locating their roots in earlier traditions, the particularities and distinct traditions of older media are often distorted or overlooked.

Consider, for instance, what is at issue in recent digital media theorists’ “rediscovery” of avant-garde and Surrealist directors like Dziga Vertov and Luis Buñuel as database filmmakers. Manovich and Marsha Kinder, among others, argue that the methods of these visionary filmmakers adhere to a database logic that is paradigmatic of the ways in which the digital culture organizes and interacts with information.[9] In forging such a parallel between older, (contested) equivalents to database logic and to digitally oriented ways of structuring the selection and combination of information, the database metaphor risks losing its contextual particularity in both historical periods. If indeed what is now identified as database logic can be traced back to pre-digital methods, then it is more indicative of a sociocultural evolutionary process of relating to information than an emblem of the ways we now interact with new media.

Lev Manovich describes Vertov’s landmark Man with a Movie Camera (1929) as “a database of new interface operations that together aim to go beyond simple human navigation through physical space,” declaring that “the avant-garde became materialized in a computer” (Manovich 2001: xxx–xxxi). While we can agree that commands like cut, copy, and paste are homologous in some respects with analog practices such as the Dadaist cut-up technique and avant-garde collage, the association between them is not as straightforward as Manovich proposes; an algorithmic approach to filmmaking undermines the traditions from which distinct and interrelated cinematic movements arise. Manovich likens the montage practices of Vertov and the New Vision movement of the 1920s to the arguably transcultural, globalized database interface of contemporary, post-GUI computing. He claims that the only area in which the connection between storage media and database forms is universal is cinema, whereby “the storage media support the narrative imagination” (233). [10]

In classifying Man with a Movie Camera as predominantly database cinema, and hence proclaiming it the “most amazing catalog of film techniques,” Manovich underrepresents other aspects of the film’s historical and political particularity (241). The only reference Manovich makes to the socio-political context of the film in his analysis of the film’s organizational techniques is when he cites, in passing, Vertov’s philosophy of the kino-eye as “the communist decoding of the world” (241). Even though the film was not intended to be a conventional realist documentary, it nonetheless retains part of its referentiality to an external reality of early twentieth century Soviet life. Admittedly, it is difficult to distinguish between certain tenets of socialist realism, indexical value, and artistic experimentation in Vertov’s work, but by limiting analysis of the film to its database-like qualities we run the risk of distorting its historical significance and reception. Manovich speculates that “the original viewers of Vertov’s film probably experienced it as one long special-effects sequence,” but he does not elaborate on how these effects acquire meaning in light of Vertov’s Kino-Glatz [Cine Eye] sensibility (241). Manovich’s reductive interpretation of the film’s contemporary reception undermines crucial factors such as the film’s resonance within the industrial-urban mythology of Communist Russia, and the film as a testament to–and commentary on–technical modernization. Furthermore, the anachronistic assertion that the film looked like “one long special-effects sequence” undermines other possible interpretations of its contemporary reception, such as the uncanny effect experienced by local audiences when seeing familiar city places in a possibly new light. Although Manovich could be mentioning the “special effects” of the film in order to propose an expanded definition of the digital, he myopically approaches the stylistic and technological innovations of avant-garde filmmaking by only considering them in relation to their contemporary digital parallels.

The database metaphor also undermines the film’s distinctive temporality, as the database is largely seen as atemporal or possessing a malleable temporality. However, even in Man with a Movie Camera, there is a sense of temporally motivated progression. The sequences amounting to a day in a Soviet city (actually, various cities) in the late 1920s are framed or intercut by mise en abyme sequences of audiences watching the film and of the film being edited, but this does not interrupt the temporal flow from dawn to dusk that motivates the film-within-a-film’s narrative progression. Regarding database cinema as a cinema that “forces the viewer to imagine there could be other configurations” can be a productive analogy, but only if we go beyond the computing metaphors of the filmic text and explore the polysemic text itself and – by extension – its multiple reception contexts (Daly 2010: 90).

Kinoautomat as Case Study for Hybrid Analytical Frameworks

A productive place to begin establishing early IC’s variable and inconsistent nature is Kinoautomat: Člověk a jeho dům (Kinoautomat: One Man and His House). The film was originally produced in 1966–7 by a Czech team led by the filmmaker Radúz Činčera. The film is significant for a number of reasons. First of all, it is cited as one of the prototypes of IC because of its use of an interactive voting system that allowed the audience to use their green (= Yes) or red (= No) buzzers to determine the development of the story. [11] The 1967 International and Universal Exposition (Expo 67) in Montreal, where Kinoautomat was showcased along with other influential works, inspired Gene Youngblood’s Expanded Cinema manifesto (1970), which expressed his synaesthetic notion of cinema as expanded consciousness. Kinoautomat is also an early demonstration of the myths associated with interactive technologies, anticipating ahead of its time the mainstream hype surrounding interactivity in the 1990s.

Kinoautomat is regarded as a prototypical example of the (debatable) database logic of IC. The name Kinoautomat draws inspiration from the idea of a movie (kino) vending machine (automat), where the chosen narrative trajectory is selected out of a pool of options. Vending machines let the consumer see the options available (either through a glass or as images) prior to making a selection. Due to their tentative similarities, it is easy to make superficial connections between the database and the vending machine, even though the analogy is problematic. Perhaps the only critic who explicitly notes the connection is Chris Hales, in observing “the often raised criticism that making choices in an interactive narrative made from pre-made segments is hardly more sophisticated than pressing the required combination of buttons on a hot-drink vending machine.” [12] Hales does not equate the organizing principles of the vending machine with the logic of a narrative database, but instead draws a parallel between the limited (inter)actions they both allow their users. Thus, Hales unwittingly taps into another Czech meaning for kino-automat, one that centers on the process of automation; in this respect, the user’s role is either that of a bystander in the automated narrative-vending process, or that of a component in the automation (in that he/she is needed to insert currency and push buttons to initiate the vending process, but has no control of the mechanisms behind the delivery of the product). The possibility of the user executing (or becoming part of) the machine’s logic resonates with Erkki Huhtamo’s view of interactive media as a type of convergence of the “two earlier models of the human-machine system: they adopt from mechanized systems the constant interplay between the ‘worker’ and the machine, sometimes to the point of ‘hybridization.’” [13] In light of this, Kinoautomat is an early testament to the interlinked sentiments of anxiety and hype surrounding interactive technologies, especially during the 1990s.

Kinoautomat’s interactive connection does not just make the film relevant to recent discussions of new media interactivity, but is also the defining trait that made it internationally appealing in the context of Expo 67. Expo 67 in Montreal, Canada, featured cutting-edge artworks from several countries, and assigned different locations (pavilions) for each country’s display. The overall theme of the Expo was cosmopolitanism, and was materialized in networked projects that encouraged mobile spectatorship and stimulated new worldviews. Paradoxically, the geographical locale of the exhibit caused the Expo to become inextricably associated with Canadian nationalism and localism. The impact of the Expo on Canadian cultural citizenship has been the focus of recent rediscovery projects of Canadian origin and sponsorship, such as the edited anthology Fluid Screens, Expanded Cinema (University of Toronto Press, 2007), and other restoration and research projects.

Much like Canada was treated as nationally distinctive and a globalized nation, the films at the Expo were regarded as national products (symbolically displayed in each country’s assigned pavilion) and also transnationally appealing. In theory, a transnational film is one that is able to reach international audiences while retaining its national flavor. Theorists Elizabeth Ezra and Terry Rowden envision a collectively referenced transnational cinema that ‘‘imagines its audiences consisting of viewers who have expectations and types of cinematic literacy that go beyond the desire for and mindlessly appreciative consumption of national narratives that audiences can identify as their ‘own.’’’ [14]

Ezra and Rowden’s definition allows for the possibility of multivalent film reception, but – at the same time – suggests that, for local audiences, transcending the national could also mean denying the aspect of the personal that is inextricably linked to the national, and thus denying an aspect of the political that is entwined with the national. The conceptualization of the transnational also tends to imply some kind of homogenization – in methodology, theorization, categorization, and so on. Arguably, many films are conceived as transnational precisely because they downplay (either consciously or in their reception contexts) the nationalism and political character of their production for the sake of crossing economical and geographical boundaries.

At first sight, Kinoautomat fits into a multifaceted understanding of transnational cinema in the sense that it has been framed as a national product of Czechoslovakia, while its universally relatable light-hearted story, as well as the novelty of the interactive format, render it appealing to a potentially global audience. The film expands on the Czech-originated tradition of the Laterna Magika that began in Prague in the late 1950s. To this day, Laterna Magika is considered a distinctively Czech theater experience that uniquely amalgamates dance performance, nonverbal film, and visual effects. In turn, Kinoautomat fused live performance, audience participation and film to create a hybrid cinematic experience. [15] Kinoautomat may be rooted in Czechoslovakian art traditions, but the diachronic appeal of interactivity enables it to transcend national and even historical boundaries. However, a closer examination of the sociopolitical context in which Kinoautomat was made not only reveals a more complex condition of its narrative, but also helps us form a more varied and nuanced understanding of interactivity and of the notion of nationhood expressed by way of an interactive format.

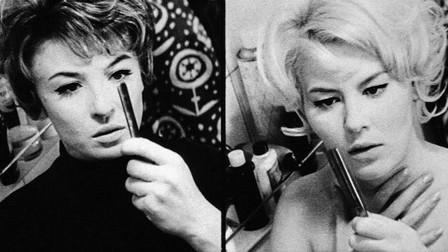

Kinoautomat’s film, titled One Man and his House, revolves around Mr. Novak -played by the famous Czech personality Miroslav Hornicek – and his interactions with other tenants that live in his building. In the film, Mr. Novak gets caught up in morally ambivalent situations. During public screenings, the audience was asked to take a vote and pick one out of two proposed options to tackle Mr. Novak’s dilemmas. At several climactic moments in the film, the live performer/ moderator would ask audience members to press the green or red button on their seats, and the majority vote would determine how the narrative proceeded. Both contemporary and recent English-language accounts of Kinoautomat mostly focus on the general outcome of the film’s interactive format, and assign it universally applicable motives. Anne Jagemann from the Art Margins Online journal, for instance, observes that the film was “rooted in its time” because it reflected the “general movement of the society, politics, and culture of the 1960s to democratize everyday life and, along similar lines, to create possibilities for greater participation in art.” In the same article, the lesser-noted sociopolitical interpretation of Kinoautomat is also mentioned: Jagemann exposes the film’s converging narrative paths, a structure that undermines the illusion of choice because all trajectories ultimately lead to the same conclusion that allows Mr. Novak to be morally acquitted for allegedly setting his building on fire. Voting whether or not to let a semi-clothed female neighbor Vera Svobodova into Mr. Novak’s apartment, for example, does not change the fact that Mr. Novak’s wife still suspects him of infidelity. Jagemann rightfully argues that the illusion of choice can be assigned a “specifically political” purpose because it acts as “an ironic parable of the socialist system that was still possible in 1967 Czechoslovakia, a year before its brutal end.” [16] This contextually specific meaning of interactivity is something that most critics gloss over in their analyses of Kinoautomat because they are more concerned with how the film fits into a general evolutionary pattern and critique of interactivity, rather than with how its specific historical and ideological context complicate the problematically universalized connotations of the term. [17] It should be noted, however, that many of the retrospective sweeping generalizations about the narrative content and formal aesthetics of works featured at Expo 67 are prefigured in the difficulty of gaining access to them now, especially those works that were site-specific, large-scale and multi-part installations. In the case of Kinoautomat, the initiative to restore and digitally remediate the film originated from the filmmaker’s daughter, who had a personal investment in the resurrection of a multi-mediated film that was in danger of becoming orphaned and possibly forgotten.

Kinoautomat: Remediated Readings

A closer analysis of the ethical dilemmas posed by Kinoautomat’s narrative reveals that it is not only the interactive format that serves as a critique of the Communist Party’s impact on Czechoslovakian society. As Mr. Novak’s apartment building grows increasingly chaotic, there is mention in the film of the need for practical systems to run things smoothly, which could be read as an allegory for the inefficient government organization in Czechoslovakia at the time. Questions about the right to intrude upon someone’s privacy, posed by the moderator to the audience, might also serve as a thinly veiled reference to police surveillance. If the audience chose to have Mr. Novak intrude the privacy of his neighbors by forced entry into their apartment, then Mr. Novak met his punishment in the form of his neighbors falsely accusing him of having an affair.

And yet, the moral code underlying the film is not consistent, and the didactic potential of the film is superseded by the semi-looping structure that governs it. For example, when Mr. Novak is chasing after his wife in his car, and a policeman tries to pull him over for speeding. Whether the viewer decides to have Mr. Novak ignore the policeman or not, Mr. Novak gets into trouble with the law. The film’s converging paths bring to the surface the fatalism that underlies its apparent freedom of narrative possibility; this is particularly felt towards the end, when Kinoautomat autonomously (that is, without the viewer’s control) fast forwards through various alternative combinations to show the viewer that the fire would have happened anyway, and thus exposes the viewers’ agency as an illusion. The performer/ live actor in the digitally-restored English dubbed version commends the viewer(s) in the usual tongue-in-cheek manner, proclaiming that, out of the “thirty two different stories that could be told, you have picked the nicest combination,” before admitting that she says that to everybody. This is in contrast to how Mr. Novak in the original film would introduce each newly selected scene by telling the audience: “You have made an excellent choice. I’m not just saying this. I do this every day and you really did make an excellent choice.” [18]

Conversely, by allowing the vending machine to take over – essentially allowing Kinoautomat become a kino-automat – and reveal in fast motion what are supposedly other possible narrative configurations, the film also perpetuates the illusion of agency. A viewer would have to watch the film at least twice to confirm that the “alternative” endings revealed in fast motion near the end of the filmic performance are, indeed, not built into the pool of options from which the viewer may choose in the interactive segments the film. Nevertheless, even a first-time viewer may be clued into the absurdity of the kinoautomat sequences. The endings that the kinoautomat movie machine zooms through at the end appear visibly doctored, as a number of conspicuous “special effects” are introduced, including arrows that seem to have been painted onto the celluloid, sepia tinting and other color filters, computer sound effects, and mathematical symbols. At this point, the film is conspicuously interacting with itself: altering its black and white cinematography and its materiality by painting onto the celluloid, and altering its established rhythm by introducing ultra fast-motion. The computer sound effects are meant to draw attention to the automatically recombinatory nature of kinoautomat, and it would not be hard for new media critics to read this move as anticipatory of the aesthetics of database and software-generated cinema.

Because the film’s pace and formal elements change radically and abruptly during the fast-motion sequences, the viewer is now consciously aware of the status he/she has been occupying all along: a passive observer of the narrative progression and a witness to a pre-determined narrative conclusion. The alternative scenarios themselves additionally challenge their own feasibility. One of the supposedly optional endings played in fast motion, for instance, concludes with Mr. Novak being set on fire by a group of terrorists – an implausible, almost cartoonish, narrative exaggeration that, in itself, appears to mock the possibility of Mr. Novak – and, by extension, the viewer – being anything more than a victim of fatality. In fact, as the film progresses, Mr. Novak’s agency appears to be gradually taken away from him; he goes from providing the seemingly omniscient voiceover in the opening scene of the film to being reduced to a victim of circumstance in the film’s conclusion.

Retrospectively, it is quite clear that Mr. Novak never possessed any agency in the first place, which also brings attention to the fact that the film’s disjunctive temporalities are never actually reconciled. In light of this realization, the voiceover belonging to Mr. Novak in the opening scene of the film is retrospectively recognized not as omniscient, but as extra-diegetic. In the opening scene, Mr. Novak’s voice is set against the backdrop of a fire being put out in his apartment building. Mr. Novak’s voiceover matter-of-factly introduces his neighbors one by one as they are fleeing the building to escape the fire. After this scene, the narrative – with the help of the live performer – moves back in time to the events leading up to the fire. The fact that the film begins (nearly) at the end of the narrative makes narrative choice seem pointless. This futility becomes even more apparent once we consider that the viewers’ choices are framed as though they influence the future outcome of the story – even though the outcome, the fire, has already “taken place” on screen. Although there is the suspended mystery of who is actually responsible for setting the building on fire, the film does not place the viewer in the role of the detective.

In other words, Kinoautomat’s narrative options are not meant to help the viewer uncover what led up to the fire through trial-and-error, but are placed in a temporally and narratively disjunctive present to give the illusion of the film being assembled in “real time.” Moreover, the point of giving the viewer options to choose from is never actually made clear: are we meant to be helping Mr. Novak discover why the fire really happened (and possibly acquit him of arson), or are we meant to alter the present-turned-future outcome (= the fire) through Mr. Novak’ s past-turned-present decisions? Mr. Novak’s self-accusatory tone in the film’s opening scene leads us to believe that we are supposed to “try to find his mistake” that caused the fire, but that does not justify why we are given multiple options on past events that are presumably non-alterable because they already happened. The cause-and-effect of the viewer’s choices is never fully disclosed and thus never fully motivated; this move is deliberately reflective on the filmmakers’ part, and its objective converges with the objective of deliberately inconclusive puzzle films. Marshall Delaney, in a 1967 article on Expo 67, quotes a Czechoslovak press release which states that the audience’s inability to change the ending of the film is meant to reflect “the experience of man in our modern society: life continues along the road of destiny irrespective of Man’s decisions.” [19] The inability to change the outcome of the narrative may seem unjustified within the narrative context, but it resonates experientially. In turn, this prompts another extra-diegetic hypothesis: if the ineffective majority vote in Kinoautomat is meant to simulate democratic decision-making, then is the performative aspect of the film suggesting that democracy is incapable of changing the end result of a societal process?

The multiple and disjunctive temporalities are apparent from the film’s opening scene – not to mention the live performance that keeps interrupting the narrative flow – and yet most of the existing critical approaches to the film have not made note of it because they have been more concerned with meta-filmic analysis and technological considerations. However, noticing the discrepancies in the narrative chronology and the non-sequentiality in the sequences extends beyond the textual level, and helps elucidate the New Wave sensibility of Kinoautomat. Deliberate forgetfulness, retrospective revision of past recollections, and indirect sociopolitical critique form aesthetic motifs and ideological tropes in many socially conscious New Wave films, including the influential works of Miloš Forman. The opening scene of Kinoautomat subtly incorporates mnemonic failure and/or past obliviousness into the subtext of the film, its mechanisms, and its allegorical dimension. On a narrative level, Mr. Novak’s voiceover is technically occurring post-fire, yet he does not appear to possess knowledge of events that happened in the past nor does he know who really set the building on fire because he (erroneously) blames himself. The detachment of Mr. Novak’s voiceover from his physical image appearing on the screen becomes more apparent when the voiceover says he never actually met his neighbor, whereas in the interactive “flashback” the two have not only met, but also got into a heated argument. The disjunction becomes even more noticeable when Mr. Novak’s image on the screen is symbolically doubled and then spread out into a split-screen in order to introduce the first two narrative options to the audience. [20]

The uncanny moment Mr. Novak first appears on the screen twice shatters any remaining illusion of narrative immersion and draws attention to formal manipulation. Rather than attributing the chronological inconsistencies and the disjunctive temporalities of the film to a failure in its narrative structure or to its incomplete loops, however, we should alternatively consider their epistemological purpose. The term “looping” has been widely used to describe Kinoautomat’s structure, but – upon close analysis of the filmic narrative – this categorization proves to be inaccurate. The insistence on the film’s loops in recent accounts attests to the tendency of reducing the original con-texts to aspects that cohere with the operative logic of new media rather than to narrative, historical, and reception-based considerations. Instead of loops, the film’s structure can more accurately be analyzed in terms of convergent narratives, inverse forking paths, and – simply – motifs and repetitions.

The way the film is narratively (dis)organized points to a tension between “knowledge as an ongoing process and a known outcome.” [21] The doubling of images, the rendering of characters into robotic automata, the splitting up of narrative into paths, and the repetition of certain moments in the film is, to apply Anna Munster’s theory, “producing a deliberate reimagining of the past rather than a faithful but tired attempt to authenticate through resemblance.” This reasoning extends beyond the narrative level, especially when the digital restoration and DVD remediation of Kinoautomat are taken into account. In this case, the above-mentioned rationale dismantles, at least partially, the burden of representation of an “original” performative film because “when the digital is harnessed to the forces of realism it inevitably fails to match up to the past.” [22]

In some ways, Kinoautomat resembles the non-hierarchal (dis)organization of multiple-draft or forking path films like Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950), Celine and Julie Go Boating/ Céline et Julie vont en bateau (Jaques Rivette, 1974), and Blind Chance/ Przypadek (Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1981), which feature initially competing yet ultimately compatible versions of virtual realities. Alternative versions of a story are presented in these films as co-existing and equally feasible possibilities, especially since an external point of reference and/ or an unequivocal or “objective” point of reliable narration are conspicuously absent. The motif of multiple paths that characterizes these films present new ways of manifesting or accessing reality: not as determined and singular, but as multivalent and irreducible to a single truth. This reasoning applies to Kinoautomat’s initially diverging narrative paths, and even to the eventual convergence of all narrative trajectories into one ending – and more acutely so if the viewer is unaware that there is only one ending to the film. Furthermore, the various possible interpretations of Kinoautomat’s metacinematic aspects – such as its critical reception, political impact, and historical value – construct the film and its surrounding discourses as equivocally multifaceted.

Presumably, the film’s dialogue and subtext could not be too directly referential to their political context, lest this should get the film banned in Czechoslovakia (as eventually happened anyway). The majority of spoken critique in the film comes from the dubious character of an ex-soldier named Captain, a mysterious figure whose sanity seems questionable (unless his paranoid behavior can be attributed to post-traumatic stress disorder, if he is indeed a World War II survivor); this, in turn, makes his tirades seem out of place in a film where most characters are primarily – but perhaps also allegorically – concerned about their individual interests. The most direct reference is when the Captain laments the chaotic system of the apartment building, and articulates the need for an efficient “East and West bloc(k)” to “orientate ourselves.” It is impossible for past and present viewers familiar with European history to dismiss the Captain’s urge for reform as simple banter, especially given the politically turbulent context. The connotations of the [dubbed] words “East and West bloc(k)” alert viewers that there is more to the film than fiction and entertainment. To more modern viewers, the film – and especially the Captain’s warnings in response to dreaded chaos – might even seem to be prophetic (by only a few years ahead) of the Prague Spring and the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

The interactive format provided a less conspicuous way to critique and simulate the democratic pretensions of the Communist Party without the film facing immediate state censorship; the interactive structure had the potential of escaping – albeit temporarily – the censors because it was a novel and unregulated technique at the time. The film’s underlying discourse makes it a national product, whereby nationhood is not perceived as a unifying force, but – rather – as an ongoing process of negotiation that encompasses internal tensions and sociopolitical segregation. Moreover, as Alan Williams has observed, cinema is an essential part of the process of defining national identity, and of stimulating debates over the meaning of “nation.” [23] Kinoautomat’s nationally specific critique, as well as its domestic reception, attests to the complex relationship between cinema and nation. According to recently publicized Czech reports, the film was popular with its audiences in Prague, where it was successfully performed from 1971 to 1972. The local success of the film – perhaps due to its sly subversion of state ideology – and the fact that the creators behind Kinoautomat were, along with other New Wave filmmakers, considered a political threat, was what prompted the ruling party to ban the film in 1972.

Interactive media consumption was, at the time, a practice that had not fully undergone social and commercial regulation. However, in the case of Kinoautomat, the interactive concept of the film was considered state property under the Communist regime, which meant that interested Hollywood executives were not permitted to license the technology. [24] The desire to regulate, institutionalize, and patent the very concept of interactivity indicates how “the opening up of new spaces of apprehension is tied to the contradictory forces of capitalist media expansion: these produce a greater democracy of image production and consumption, and greater social and economic control over images.” [25] This might explain why the (not-yet-mainstreamed) experimental approaches to IC make use of taboos and morality as a testing ground for proposing new cinematic ethics and new criteria for the regulation of interactive production and consumption.

The introduction of interactive ways of film viewing as testing ground for new modes of perception is not a novel one. Sergei Eisenstein influentially recognized the potential of cinema in transforming public consciousness through the dialectical struggle of visual elements, which results in the production of a “graphically undepictable” third element that lies between sensuous image and abstract thought. [26] Additionally, film historians Vanessa R. Schwartz and Leo Charney have associated early cinema with the culture of modernity in Cinema and the Invention of Modern Life (1995), while Tom Gunning has argued that early recorded attractions such as virtual rollercoaster rides prepared viewers for facing the shocks of modernity. More recently, Michael Cowan has historicized Weimar rebus films (moving picture puzzles) by linking the universal activity of puzzle solving to a “forum for testing new modes of distracted perception and divided attention particularly appropriate to the urban environment [in the 1920s].” [27] Cowan’s interpretation of rebus films is the modernist equivalent to Expo 67’s arguably posthumanist objective of broadening modes of perception in the wake of a new cosmopolitan awareness. Approached from this angle, Kinoautomat adheres to the overall theme for the exhibition, and can accordingly be seen as an advocate of new ways of traversing the world through its expanded spectatorship model.

However, if the aforementioned allegorical dimension of Kinoautomat is taken into account, some significant discrepancies arise between Expo 67’s democratizing objectives and, by extension, Kinoautomat as “world cinema.” In fact, the analysis of Kinoautomat fluctuates according to context and historical or theoretical motives – from exploring new modes of subjectivity and introducing a new cinematic perception, to reflecting how audiences behave socially (including the simulation of social powerlessness). The environment of Expo 67 no doubt endowed the performance and reception of Kinoautomat with democratizing and globalizing intentions. However, the experience of the film takes on different meanings if we consider other exhibition contexts, such as those in Prague in the years following the Expo. While in the years before 1970 Kinoautomat could be seen as a clever attempt to critique the status quo by outwitting the censors, in the 1970s the power of the Communist media had fully waned and a general apathy on the public’s behalf meant that nobody even tried to outwit the censors anymore. [28]

Kinoautomat seems to anticipate this apathy, urging people to take control of the media they consume, but also betraying a tone of resignation in the predetermined outcome of this apparent agency. In his account of the post-normalization status of Czech media in the early 1970s, journalist Jan Čulík says that the media’s primarily emotional campaigns “blotted out all meaningful discourse, but the meaning of these campaigns was purely ritualistic – no one believed what was being said. The medium was the message. What mattered was that rituals were being carried out.” [29] This account shifts the focus from the original intentions attributed to Kinoautomat’s interactivity (both within the context of Expo 67 and Czechoslovakia in the mid-1960s) to an additional possibility behind the use of interactivity; it raises the question whether the utopianism partially attached to Kinoautomat’s interactivity is meant to ironically reflect the utopianism in Socialism and Communist ideology. Conversely, is the potential cynicism that undercuts this utopianism a sign of reservation about a Socialist alternative, especially given the growing apathy of the public in 1970s Czechoslovakia?

Robert Rosenstone is among the historians who have argued that a film’s performative aspects do not necessarily hinder its potential to present a compelling argument for historical mythmaking as an integral part of history. [30] This is an idea that has been explored in interactive works concerned with the relationship between the personal, the historical, and the fictional; examples include Bleeding Through: Layers of Los Angeles 1920–1986 (Norman Klein and Andreas Kratky, 2003) and Terminal Time (Steffi Domike, Michael Mateas, Paul Vanouse, 1999). Films such as these have managed to transform the initially oxymoronic practice of “interactive documentary” by reconciling “interactivity” and “documentary” in order to spearhead the newly emerging practice of i-docs. The inconsistent meaning(s) of Kinoautomat is thus something that may be more historically valuable than aspects such as the indexical value of footage from the streets of Prague in the 1960s, the interactive mechanism, and even the underlying political commentary.

Even within the context of Kinoautomat’s performance, the idea of rewriting and revising the past is reflectively expressed to the audience. At one point, the performer asks the audience to reconsider their decision, and offers them the chance to re-cast their vote. The performer reminds viewers that they “now have an opportunity to do something that in real life wouldn’t be possible, [and] decide what has already been decided.” Although the film does not truly allow the audience to actively rewrite the outcome of the narrative – and only partially allows for the re-sequencing of the master narrative – the audience is still able to revisit and question some events that were previously taken for granted, such as Mr. Novak’s involvement in the outbreak of the fire. The power to “decide what has already been decided” does not lie within the realm of narrative control, but is instead located in the viewer’s ability to retrospectively rethink and reflect on past assumptions about the film and, by extension, meditate on notions of chance, fate, agency, and cultural politics. The feature of narrative interactivity – with its connotations of reordering, temporal manipulation, and diegetic control – corresponds to, and expands, Rosenstone’s argument that film increases the awareness “that we can never truly know the past, but can only continually play with, reconfigure, and try to make meaning out of the traces it has left behind.” [31]

After a few viewings, it becomes evident that the film is organized around a master narrative, and that even most of its performative aspects are largely scripted. In contrast, the creation of a foundational historical narrative is hindered by the fact that past contexts of Kinoautomat are themselves unstable – which is, of course, a claim that can be made for any work of art or cultural artifact. Historians who argue that “only through the textual [and, in this case, filmic and technological] residues of the past can we recover putative contexts,” point out that the result of this approach “is an inevitable circularity between texts and contexts that prevents the latter from becoming the prior determining factor.” [32] Historian Martin Jay contends that:

we may not be able to understand a text or document without contextualizing it, but contexts are themselves preserved only in textual or documentary residues, even if we expand the latter to include nonlinguistic traces of the past. And those texts need to be interpreted in the present to establish the putative past context that will then be available to explain still other texts. [33]

Jay’s assessment is particularly apt when applied to the process of digital remediation and recontextualization of Kinoautomat, and once again eases the burden of representation and reorients the objectives of media historiography.

From Kinoautomat to Digital Repository? An Applied Study of Media Excavation

Kinoautomat as an IC case study stimulates additional areas of inquiry when its recent digitization and international circulation are taken into account. In 2007, forty years after Kinoautomat’s debut at Expo ’67, the original film (including its performance component) was re-released to the international public via a limited series of screenings. [34] A digitized DVD version of the film then followed, and was made internationally available a few years ago. My first encounter with the film was in its DVD version. Prior to watching and interacting with the DVD, I had the impression that the film itself was formally and narratively unremarkable because none of the critiques I had read mentioned anything besides the basic plot premise that motivates the interactive component. Upon watching the dubbed English version of the film for the first time, I was surprised to discover that sophisticated editing techniques and caustic humor actually made the film engaging to watch as a conventional film, without even needing an interactive gimmick to make it appealing.

The DVD version of Kinoautomat includes the original feature film and a newly recorded performance by a moderator (with the option of purchasing a copy dubbed in either English, German, or Italian; the dubbed English version features an English-speaking moderator). Apparently, the typical Czech humor characteristic in films from the 1960s is untranslatable, or at least was not detected by a non-Czech viewer such as myself in the dubbed version. This makes me suspect that the original version was not faithfully dubbed, just as the original speech of the moderator was adapted for a digitally savvy audience.

The DVD version visibly reflects on the process of digitization and restoration; attentive modern viewers will be aware of the fact that they are watching the “translation” of a performative cinematic event into a digitally compacted object. And that object, in turn, is – at least superficially – meant to generate an event of its own: an interactive experience (re)tailored for domestic and, even, individual viewing. In fact, the restored version is more concerned with contextualizing the Kinoautomat experience than transparently (re)mediating the film, and thus turns it into a historical artifact meant to be studied and appreciated, rather than to be watched and interacted with. The moderator first appears on the television screen to introduce the film as an example of “prehistoric interactivity” and stress its historical importance to modern viewers. Throughout the film, the desire – and, certainly, the burden of both historical and technological representation – to convey to modern audiences the original screening conditions interferes with the attempt to produce a relatable digital product, much less a satisfactory viewing experience.

In my estimation, if the viewer has not experienced a Kinoautomat public screening, then she or he will be largely unable to tell which “original” aspects of the performative film have been preserved for domestic viewing in this format. The moderator’s speech is clearly geared towards modern audiences, as it draws attention to issues of materiality and mediation that resonate with contemporary discourses of digital/ analog, database/ narrative, and other dichotomies. The film begins with the illusion that the projector is broken and the film reel is damaged – which does not apply to the home DVD viewing experience. The moderator attempts to explain this glitch (or, in this case, simulated glitch) in asking: “can the film of a computer be broken? Most likely not,” and goes on to say that every Kinoautomat performance in the 1960s and 70s began with this pretend – yet at the time plausible – malfunction.

The moderator in the Kinoautomat DVD bears the responsibility of not just moderating the viewer’s voting process, but also conveying the extra-filmic dimensions to a modern audience. The restoration of the film to the public and its recognition as part of the Czechoslovakian New Wave has made it a national(ist) artifact. Yet, the English version of its DVD downplays its cultural significance by lifting it from this national-political context, and focusing almost entirely on its notional forward-thinking use of technology. In fact, the promotional trailer for the DVD edition does a better job contextualizing the film in its historical moment, paradoxically through the use of digital remixing.

The trailer for the digitally restored Kinoautomat can be examined through the twin lenses of the mashup and the trailer re-cut: two digital remixing techniques usually associated with context collapse, inauthenticity, and ahistoricity. [35] Mashups typically fuse discrete found footage sources into a derivative work that gives “original” material a new meaning. Mashups combine footage from seemingly incongruent sources, and have the ability to efface political, cultural, and other specificities for the sake of presenting a unified argument through continuity editing and montage. Trailer re-cuts twist the original film’s trailer by altering the voiceover and changing the original genre. There is no original Kinoautomat trailer, nor does its digital trailer fully reflect the mashup aesthetic; nevertheless, the trailer mimics some of the techniques argumentatively used in both mashups and re-cuts. First of all, the trailer remixes documentary footage of the Communist congress with a re-cut voiceover that mashes up the original audio with audio from an interactive Kinoautomat screening. In this sense, the trailer collapses the boundary between documentary footage and fictional narrative to draw attention to fictions of Communism, as the editing points to the film’s complex relationship between fiction, entertainment, and allegory.

Kinoautomat’s digital remix trailer achieves two objectives that are usually seen as irreconcilable in the context of digital remixing: the trailer (loosely) places the film in context and also makes it relatable to the digital generation. The trailer appeals to international online audiences via its use of digital language tools and viral circulation through sites like YouTube. Eli Horwatt suggests that digital remixing exemplifies how found footage image (re)making “has become relevant to new generations through the appropriation of contemporary images in an effort to address pertinent socio-political issues.” [36]

Nonetheless, the appropriation and re-contextualization of original sources and the historical moments they represent occurs in a simplified and reductive form. Linda Hutcheon argues that, thanks to the element of parody that is inherent in the digital remix, audiences come to terms with the texts of “that rich and intimidating legacy of the past.” [37] As with many processes of retroactive contextualization, the past is articulated in terms that are particularly resonant for present-day viewers. The ideological heavy-handedness of the Kinoautomat trailer is evident, for starters, in the introduction text that prefaces both the remix trailer and the historical status of Kinoautomat in terms that are understandable to current international audiences and that coincide with the mythologies of interactivity. Through the mash-up of documentary footage and audio from Kinoautomat’s performance, the trailer reflectively addresses how the film was intended “to demonstrate the absurdity of the [Communist] regime in contrast to free voting in a film,” and simultaneously reinforces the fantasy of control associated with IC. [38] The trailer does not dwell on the problematic aspects of free voting in the film – which itself provides another layer of complexity to the film’s underlying commentary. In fact, the trailer suggests that the film’s democratic free voting was contradictory to the Communist Party’s decision-making process. The way the film worked, however, is far more complex than the trailer’s attempt to summarize how the film was performed.

Beyond its representational (in)accuracy, though, the trailer is valuable in other ways. The editing techniques used to compile the trailer – the mash-up and the re-cut – have been traditionally used to subvert existing meanings and oppose teleological interpretation. In light of this, the trailer appropriately renders the film’s history malleable by subverting contextual fixity. The trailer hints at the uncertainty of conclusive contextualization and posits its own multi-platform and cross-contextual (yet not open-ended) mode as an alternative means of mediating the history of media.

Simply put, the film – like its digital trailer – deliberately tricked the audience into thinking it had control over the direction of the narrative, albeit superficially (the recontextualized digital version hints at contemporary audiences’ disbelief regarding Kinoautomat’s promises of narrative control). In actuality, there was only one possible (happy) ending to the story, and even the trajectories “chosen” by the audience reached the same conclusion at the end of each scene. There were even some speculative guesses, where the performer asked the audience to make a guess with no influence on the direction of the story. The film’s quasi-looping (rather than branching-out or rhizomatic) design adds a more complex dimension to the subversiveness of the work – a dimension that cannot fully be conveyed through the trailer, or even fully grasped during a home viewing of the DVD. This is because the social and performative aspects of the work cannot be fully conveyed or remediated. The main intention behind the use of interactivity was to simulate the illusion of free vote; in Communist Czechoslovakia even entertainment was censored, hence the futility of majority voting.

The DVD edition of Kinoautomat, as well as recent public screenings, makes the illusion of free voting more transparent than original screenings of the film. The re-recorded accompanying performance to the dubbed version of the film often hints at the audience’s limited role in the construction of the film, and – at the beginning of the introduction – outright poses the question of whether Kinoautomat can ever play what you choose. If in doubt, the viewer watching the DVD at home can easily replay the film (although the impossibility of rewinding scenes makes it less easy to navigate) and, after trying out various combinations, confirm that all paths lead to the same ending. By contrast, Kinoautomat’s contemporary audiences watched the performance in a public setting, and had a different experience than the modern home viewer. Contemporary audiences were probably left in doubt as to the actual impact of the voting process, especially if they only got to experience the film once.

Nonetheless, part of the social value of the film was seeing how the majority voted, especially when it came to morally ambiguous situations that made Mr. Novak choose between being a dutiful citizen or chase after his wife. Furthermore, the public performance of the film makes for an altogether different experience than a domestic/individual screening, especially because the question of choice (real or imagined) becomes a collectively negotiated process. The ethical dilemmas in Kinoautomat are more nuanced and less polarized than those in choose-your-own-adventure films, and required some deliberation on the audience’s part. In public screenings of Kinoautomat, the deliberation process might have been more significant than whether or not individual (and, by extension majority) votes count. Initially, Činčera and his team did not anticipate the impact interactivity would have on the audience’s social dynamic. After the first few screenings at Expo ’67, the live show was adapted to not only acknowledge the audience as part of the performance, but to also enhance interaction among audience members. In a 1967 interview with LIFE magazine, Činčera commented on aspects that would later preoccupy empirical studies on interactivity as well as revisionist approaches to cinematic identification. After observing early audience response to Kinoautomat, Činčera declared the work a “sociological and psychological study about group behaviour,” and a means of “learning that people decide not on a moral code but on what they like to see.” [39] Seeing Kinoautomat as both social experiment and historical artifact shifts the focus from the mechanics of interactivity to the impact of the film’s ethical dilemmas on the audience dynamic, and to interactivity as a stimulus for social interaction.

Unfortunately, very little information has survived regarding how contemporary audiences responded to specific scenarios they encountered in the film, and how those scenarios affected the audience dynamic. This might be because the film-as-performance was primarily enjoyed as a transient experience, and thus there was no lasting record of detailed audience voting patterns. The few collective voting preferences that have survived are those considered noteworthy at the time in terms of generating more attention for the film, such as the fact (or rumor, depending on the source) that the only time viewers voted No to Mr. Novak allowing his half-naked neighbor into his apartment was when a group of nuns was in the audience.

The fact that the surviving audience responses to Kinoautomat have been quantified speaks to the wider tendency in film reception studies, whereby the results that forge trends in viewing habits (or the ones that form notable exceptions to those patterns) are the ones that usually comprise lasting historical records. In a sense, the historical does not take into consideration the individual that is part of the collective. More specifically, film history does not consider individual experiences that are part of a collective (and often abstract) “body” of spectatorship. Vivian Sobchack notes that, in the practices of both mainstream cinema and in theories of spectatorship, “the particular human lived-body (specifically lived as ‘my body’)” is missing because it is “in excess of the historical and analytic systems available to codify, contain, and even negate it.” [40] Thus, the lack of significant audience response analyses to Kinoautomat point to irreparable yet unavoidable gaps in studies of film reception, extending beyond empirical records and indicating the crucial omission of phenomenological and biocultural considerations from the notion of spectatorship.

The fact that the interactive component overshadows all other contextual and narrative considerations (that traditional film analysis would otherwise consider) in the recent scholarship of Kinoautomat is indicative of what is at stake when new methodologies shift the priorities of existing fields of study. In this case, Kinoautomat’s “new medianess” is a double-edged sword: certain of its formal and performative resemblances to operations of digital media have prompted its academic excavation and association with digital discourses, but at the cost of marginalizing other equally valuable aspects such as historical significance, audience reception, and sheer film appreciation. Subsequently, if these aspects were to be fully integrated into digital media studies, then the scope of media studies – as well as the notion of “digital culture” – would be informed with even more complexity and cross-cultural perspectives.

The fragmented rediscovery of influential works like Kinoautomat, along with the difficulty of broad-ranging cross-contextual analysis, is an object lesson in how film and media studies should (re)constitute and productively engage with the material-procedural diversity and inconsistencies of both digital and filmic encounters, without necessarily conflating the two. As Gitelman and Pingree assert, when the histories of each medium are forgotten or ignored, “we lose a kind of understanding more substantive than either the commercially interested definitions spun by today’s media corporations or the causal plots of technological innovation offered by some historians.” [41] Ultimately, Kinoautomat makes a powerful case for considering the inherently political nature of film preservation and restoration, and for regarding the practices of archiving and remediation as cultural processes that produce and codify cinematic heritage. [42]

NOTES

[1] In The Language of New Media (MIT Press, 2001), Lev Manovich identifies interactivity as one of the traits of new media, and argues that this interactive nature is what allows the user to become “the co-author of a work” (49). But, later on in his book, Manovich admits: “to call computer media ‘interactive’ is meaningless – it simply means stating the most basic fact about computers” (55).

[2] Marsha Kinder defines database narratives as structures that expose or thematize “the dual processes of selection and combination that lie at the heart of all stories and that are crucial to language: the selection of particular data (characters, images, sounds, events) form a series of databases or paradigms, which are then combined to generate specific tales” (Kinder 2002b: 6). Mike Figgis’s Timecode (2000), as an example, illustrates the database aesthetic in the form of four split screen sections displaying overlapping actions shot in the style of real-time surveillance footage.

[3] Lev Manovich identifies interactivity as one of the traits of new media, and argues that this interactive nature is what allows the user to become “the co-author of a work” (Manovich 2001: 49). But, later on in his book, Manovich admits that “to call computer media ‘interactive’ is meaningless–it simply means stating the most basic fact about computers” (55).

[4] Edward Branigan’s definition of narrative as “a way of organizing spatial and temporal data into a cause-effect chain of events with a beginning, middle and end” is a useful starting point for thinking about narrative as a mode of cultural production and a means of comprehending the world. Edward Branigan, Narrative Comprehension and Film (New York: Routledge, 1992), p.3. Marsha Kinder defines database narratives as structures that expose or thematize “the dual processes of selection and combination that lie at the heart of all stories and that are crucial to language: the selection of particular data (characters, images, sounds, events) form a series of databases or paradigms, which are then combined to generate specific tales.” Marsha Kinder, “Hot Spots, Avatars, and Narrative Fields Forever: Buñuel’s Legacy for New Digital Media and Interactive Database Narrative,” Film Quarterly, 55 (4) Summer 2002, p.6.

[5] Kristen Daly, “Cinema 3.0: The Interactive Image,” in Cinema Journal, 50 (1) Fall 2010, 83.

[6] Thomas Elsaesser, “The Mind-Game Film,” in Puzzle Films: Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema, ed. Warren Buckland (Malden, MA: Warren Buckland, 2009), p.21.

[7] Ibid., 29.

[8] Timothy Corrigan, Cinema Without Walls: Movies and Culture After Vietnam (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1991).

[9] Timothy Corrigan, Cinema Without Walls: Movies and Culture After Vietnam (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1991).

[10] It should be noted that Manovich’s views on the relationship between narrative and database are not consistent if we take his entire body of work into account. Sometimes he sees the two as contradictory, while other times he sees them as supplementary.

[11] In theaters equipped with custom electronic voting consoles (including the space at Expo 67, and more recent screening locations), the viewers’ color-coded votes were displayed along the periphery of the screen. In some other conventional theaters, including Prague screenings, the voting was done using color-coded cards.

[12] Chris Hales, “Cinematic Interaction: From Kinoautomat to Cause and Effect,” Digital Creativity, 16(1) 2005, 64.

[13] Erkki Huhtamo, “From Cybernation to Interaction: A Contribution to An Archaeology of Interactivity,” in The Digital Dialectic: New Essays on New Media, ed. Peter Lunenfeld (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2000), p.107.

[14] Elizabeth Ezra and Terry Rowden, Transnational Cinema: The Film Reader (New York: Routledge, 2006), p.5

[15] Historical information paraphrased from the Kinoautomat official website, http://www.kinoautomat.cz/index.htm , and Chris Hale’s article, “Cinematic Interaction: From Kinoautomat to Cause and Effect,” in Digital Creativity, 16(1)2005, pp. 54–64.

[16] Anne Jagemann, Kinoautomat DVD review, Art Margins Online, 12/31/2009. Accessed Febuary 2012. http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/6-film-a-video/549-raduz-cincera-jan-rohac-vladimir-svitacek-qkinoautomat-clovek-jeho-dum-one-man-houseq-dvd-review

[17] A notable exception to this tendency is Nico Carpentier’s recently published book, Media and Participation: A site of ideological-democratic struggle (Chicago: Intellect, 2011), which contains a well-rounded analysis of Kinoautomat.

[18] Michael Naimark, “Interval trip report: World’s first interactive filmmaker”, 1998. http://www.naimark.net/writing/trips/praguetrip.html . Accessed February 2012.

[19] Marshall Delaney, “Film Techniques at Expo 67,” Saturday Night (Canada), 82 (7) July 1967, pp. 33-35

[20] In the digital version of the film, the repetitive (and presumably unintentional) glitch that momentarily freezes the film when the hall porter is introduced contributes an additional layer of disjunction that undercuts any effort towards narrative immersion and draws attention to the materiality of the DVD and the remediation process from celluloid to disc.

[21] Anna Munster, Materializing New Media: Embodiment in Information Aesthetics (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth, 2006), p.81.

[22] Ibid., 81.

[23] Alan Williams, “Introduction,” in Film and Nationalism, ed. Alan Williams (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2002), 4.

[24] Factual information taken from Ian Willoughby’s article, “Groundbreaking Czechoslovak interactive film revived 40 years later” (06/14/2007), posted on the Czech radio website Radio Praha.

[25] Janine Marchessault, “Multi-screens and future cinema: The Labyrinth Project at Expo 67,” in Janine Marchessault and Susan Lord (eds), Fluid Screens, Expanded Cinema (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), pp. 39-40.

[26] Sergei Eisenstein, “The Cinematographic Principle and the Ideogram,” in Film Form: Essays in Film Theory, trans. Jay Leda (San Diego, CA: Harcourt, 1977), 30.

[27] Michael Cowan, “Moving Picture Puzzles: Training Urban Perception in the Weimar ‘Rebus Films,’” Screen 51, no. 3 (Autumn 2010), 200. Paul Leni’s Rebus Film Nr. 1 (1925) is an example of a rebus film. Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Z2zwDOZ_qI

[28] The most passionate (and overtly biased) accounts of the growing apathy among the public are documented by contributors including Tomáš Pecina on the Czech political and cultural online website Britské listy (British letters). Even though the listy is notorious for publishing exposés and conspiracy theories, it is also known for its risqué and uncensored opinion pieces, which make it more reliable as a historical discussion of Czechoslovakian politics in the 1960s and 70s than the contemporary government-sanctioned reports. Britské listy, http://www.blisty.cz/ (Accessed June 2012).

[29] Jan Čulík, “There was no censorship in Czechoslovakia in the 1970s and 1980s.” Lecture presented at University College, London, 25 April 2008. http://www.arts.gla.ac.uk/Slavonic/Censorship.htm

[30] See for example Robert A. Rosenstone, Visions of the Past: The Challenge of Film to our Idea of History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), and History on Film/ Film on History (London: Longman, 2006).

[31]

History on Film/ Film on History (London: Longman, 2006), p.164.

[32]

Martin Jay, “Historical explanation and the event: Reflections on the limits of contextualization,” New Literary History, vol. 42, no. 4 (Autumn 2011), p. 558.

[33]

Ibid.

[34]

After the film’s 1972 ban in Czechoslovakia, the film was last screened as a performance piece at Expo 74, and briefly broadcast on Czech television in the 1990s to an unsatisfied public.

35 Watch the official English language trailer to the digitally remastered DVD edition of Kinoautomat here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s6mnuGIcjXo

[366] Eli Horwatt. “A Taxonomy of Digital Video Remixing: Contemporary Found Footage Practice on the Internet,” in Scope: An Online Journal of Film & TV Studies, 2010.

[37]

Ibid.

38 Of course, this “intended” ideological purpose was not obvious in Kinoautomat’s original exhibition contexts, nor was it ever publically confirmed by the film’s creators (although Činčera’s daughter and others have spoken about it in interviews given after his death). The political dimension of the film was toned down during the 1960–70s in both international expos and local screenings.

[39]

Frank Kappler, “The Mixed Media – Communication that Puzzles, Excites and Involves,” in LIFE 63(2) 1967, p. 28C.

[40]

, The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience (P rinceton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), p. 147.

[41]

Lisa Gitelman and Geoffrey B. Pingree (eds), New Media, 1740-1915 (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003), p. xv.

42 Caroline Frick demonstrates these principles through cross-cultural comparative study and extensive examination of American film preservation practices in her book, Saving Cinema: The Politics of Preservation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).