Young Duke Cameron lies mortally wounded on a smoky, bloody Gettysburg battlefield. Suddenly, a northern youth appears above him, bayonet poised to strike him through. A glimmer of recognition passes over the youth’s face. The wounded Rebel is his childhood chum. As the Yankee lowers his rifle and bends over his dying friend, a shot rings out. He falls to the ground beside his chum and they die in each other’s arms.[1]

The recollections of this dramatic death scene are those of Australian-born actor André de Beranger, who played “young Duke Cameron”. The year is 1914, but the only shooting being done here is with a movie camera. The location of the “battlefield” is a ravine in the San Fernando Valley, outside Hollywood; one of the sets for DW Griffith’s twelve-reel Civil War blockbuster The Birth of a Nation (David W. Griffith Corporation/Epoch Producing Corporation, 1915). Griffith began filming on 4 July, American Independence Day – marking a display of nationalism on his part as well as a flair for publicity. A week before Griffith started shooting in California, however, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, had been assassinated in Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia. Within a few weeks, Europe was at war. While Griffith and his cast and crew played Confederate and Yankee soldiers in the warmth of a California summer, creating special effects using smoke and mirrors, thousands of young men in countries across Europe and the British Empire began enlisting to serve in a war many thought of as a great adventure, and one that would be over in a few months – not much longer than Griffith’s eventual film shoot. Instead, the Great War, as it came to be known, lasted four years and killed over ten million people. Because the United States delayed its entry into the war until 1917, Hollywood was able to cement its position as the dominant player in the fledgling film industry as studios shut all over Europe and Great Britain.

De Beranger acted in and directed movies in the United States, England and Europe, during the early years of the twentieth century, cast in D.W. Griffith and Ernst Lubitsch movies and co-starring with the likes of Douglas Fairbanks, Lillian Gish and Clara Bow. His film career faded, however, after the introduction of talkies and when the Great Depression closed many studios. Today he is almost unknown either in Australia or the United States, lucky to rate even a footnote in accounts of the golden days of Hollywood or in biographies or autobiographies by his contemporaries. It is difficult to verify de Beranger’s own versions of his life and career, so tangled are the narratives. The most extraordinary of these is his war service record. He claimed to have served with the Australian forces, without ever specifying where, and to have been a fighter pilot with a crack Canadian-based squadron during the Great War. Australian and Canadian military archives reveal no official records for André de Beranger, or for George Augustus Beringer. He is a man missing in action. With a service record set against the backdrop of Hollywood opportunism and the practice of splicing real war footage into films for action sequences, he was probably one of many in the industry who chose to blur the line between fact and fiction, without questioning the morality of the process. Playing the role of young Duke Cameron in The Birth of a Nation might have been the closest de Beranger ever came to active service.

The merging of fact and fiction onscreen that began in the last decades of the nineteenth century, and the use of “war footage” proved to be immediately popular with audiences. It is not easy to ascertain whether audiences at the time could identify, or even cared, that they were watching fake footage, as long as it was action entertainment. The outbreak of the Spanish-American war in 1898 provided plenty of opportunities, and cameramen from both the American Edison and Biograph companies went to Cuba to film soldiers and ships. Cameramen J Stuart Blackton and Albert E Smith, however, worked from home, buying postcards of ships from the American and Spanish fleets and setting up a little battle scene on the roof of the Vitagraph studio on Nassau Street in New York City. The cutout cardboard ships were nailed to small pieces of wood and set floating on an inch of water; a few pinches of gunpowder were placed behind each ship – “not too many for a major sea engagement of this sort” according to Smith – to provide smoke and explosions for their short film The Battle of Manila Bay (American Vitagraph Company, 1898).[2]

The development of the film industry coincided with the growth of US colonial imperialism; the two fed each other. By 1915, film was the fourth largest industry in the United States, with some ten million people allegedly seeing a film each day, according to Vachel Lindsay in his landmark survey The Art of the Moving Picture, published in that year.[3] War images were received as entertainment as well as a source of factual information, and the practice of splicing real “documentary” footage into feature films increased as soon as war was declared in Europe, much of the material being shot in France and Germany. From the first months of what was initially referred to as the “European War”, American film companies attempted to exploit public interest in actual footage from the front lines of battle. The war was not expected to last more than a few months, initially, and the real footage provided ready-made drama, saving time and money on film production. It was important for film-makers to cash in before the war in Europe became old news and cinema audiences turned their attention elsewhere.

As early as August 1914, The Moving Picture World ran advertisements such as one from Ramo Films Inc in New York, headlined “War! War! War!”

The War of Wars

or the Franco-German Invasion of 1914

400 Stupendous Scenes

Taken on the Actual Battlefields of France

Will Be Released Within a Week

The First Authentic Photoplay to Depict the Great Events of

the Reigning Sensation of the World

The Austro-Servian [sic] Film Co., with offices at 220 West 42 Street, Manhattan, took a hard-sell approach with distributors, declaring:

War and More War

EVERYBODY Reads About the European War

EVERYBODY Talks About the European War

EVERYBODY is Interested in the European War

EVERYBODY Wants to See Photo-Plays of the European War

“WITH SERB AND AUSTRIAN”

4 Reels

Is the First Subject of Its Kind Put On a Hungry Market

This is Not a Bawling Bull but Good Hard Facts

If You Don’t Realize It to Your Benefit You’ll Realize It to Your Loss

Even more provocative was an advertisement from The Kaiser Film Company, a couple of blocks away on West 40 Street:

COMING

Ready August 15th

Actual, Authentic, Real and Only Motion Picture of

THE MAN OF THE HOUR

KAISER WILLIAM [sic] II

His soldiers in full action. Scenes from the Theatre of the World’s Greatest War.

We positively guarantee that the scenes showing Kaiser William were taken from actual life and by special permission of the Kaiser himself.

Some of the American film industry’s most extraordinary blends of fact and fiction occurred in D.W. Griffith’s 1917 drama Hearts of the World (D.W. Griffith Productions/Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, 1917) and its 1918 sequel The Great Love (D.W. Griffith Productions/Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, 1918). The films portray the lives of a young couple growing up in a little French village where peace is shattered by the intrusion of war. Partly financed by the British Government’s War Office, and including footage actually shot in the trenches in France under Griffith’s direction, Hearts of the World starred not only Dorothy and Lillian Gish and their mother – with Lillian’s peasant girl costume designed and created by Nathan of London – but also British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and French Premier René Viviani playing themselves. The New York Times review of the sequel The Great Love commended:

Mr. Griffith for the deftness with which he can link fact and fiction in an almost continuous chain [taking] some remarkable scenes of London during an air raid, a great English munitions plant, fighting at the Front, British hospitals, and other centers of interest and activity, and skillfully [tying] them together with a story of love and German plotters.[4]

Griffith actually shot much of Hearts of the World on Salisbury Plain in England and the Lasky Ranch in California, and spliced this together with German documentary footage he had purchased.[5] And he was probably the originator of at least some of the stories circulating at the time of the film’s release, suggesting he and his actors and crew had put themselves in real danger at the Front. The only member of the company allowed to visit the Front was Griffith himself; his cameraman Johann Gottlob Wilhelm (Billy) Bitzer, owing to his German ancestry, was not even permitted to enter France, forcing Griffith to make do with an unnamed and uncredited army cameraman.

Fact and fiction on film in some ways replicated the lives of the actors who were making their careers at this time. De Beranger offers an interesting case in point. Like Bitzer, he was also of German stock, and the war service record he seems to have fabricated served not only to enhance his reputation and career prospects, but also to hide both his background and his illegal entry into the United States. He had grown up in Australia, leaving Sydney for Canada in 1912, at the age of nineteen, arriving in Vancouver and then traveling to Toronto, possibly with a stage actor colleague. From Toronto, de Beranger seems to have slipped across the United States-Canadian border – as had a young Samuel Goldwyn several years earlier – to start a new life with a new identity. De Beranger was a man without official papers.

Disguising German ancestry resulted in the transformation of George Augustus Beringer into Frenchman Andre de Beranger, although invented names and backgrounds were commonplace in Hollywood. De Beranger, born in inner-city Sydney in 1893, was in fact the youngest son of a German engine-fitter, Adam Beringer, who had settled with his wife and children in New South Wales in 1885. Adam Beringer became a naturalised Australian in 1905, yet two of his Australian-born sons, one of whom was an electrical engineer and the other a telephone mechanic, were required, under the laws of the time, to give depositions to the Australian Special Intelligence Bureau during the Great War, in May 1918, both being classified as “Enemy Subjects in the Public Service”.[6]

A world away in Hollywood, André de Beranger provided for film studio publicity departments the stylish fabrication of a French identity, birth on a French ocean liner off the coast of Australia, and an education in Paris, specialising in law and architecture. The name “André de Beranger” seems appropriately debonair and aristocratic, and until the advent of talkies, lack of an authentic French accent would not have posed problems. He played foppish Frenchmen in at least a dozen silent films, including The Popular Sin (Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, 1926), Altars of Desire (MGM, 1927), If I Were Single (Warner Bros Pictures, 1927), and Beware of Bachelors (Warner Bros Pictures, 1928). Such affectation was not uncommon. Actor and director Henry Lehrman had first appeared at the Biograph Studios in New York in 1909, speaking with an absurd French accent, and claiming to have considerable experience with the French film company Pathé. Lehrman was in fact “a streetcar conductor on the 14th Street line who became enamoured of film people while transporting them to work”.[7] D.W. Griffith was not taken in by “Pathé” Lehrman’s accent and story, but he found him amusing and cast him as an extra.

Bluff and versatility were the means by which many people entered the film industry, particularly during the early decades of constant technological development and innovation. Many actors also wrote scripts and assisted with direction, and de Beranger was soon to became one of them. ‘Directing’ at the time, however, was not an elevated role. The director was there to coordinate storyline, camera and actors – a sort of go-between. It was the cameramen who were the real artists, manipulating machinery and the available light. These brilliant technicians were to be much in demand during the war for their ability to capture images of battle. By the end of 1914, de Beranger was described in the trade journal The Moving Picture World as having been “an assistant director to Mr. D.W. Griffith for almost a year. Much of this work would have been on The Birth of a Nation.

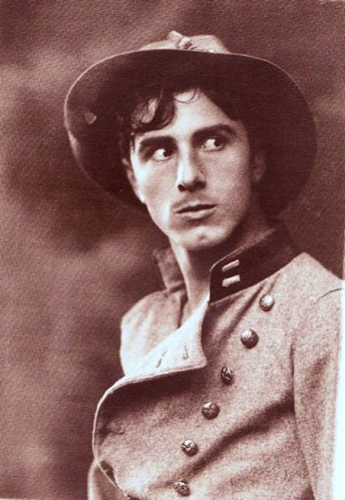

Wells Vincent studio portrait of Andre de Beranger as young Duke Cameron, in the uniform of a Confederate soldier (The Birth of a Nation)

Griffith had employed a cast of his favourite actors, including Lillian Gish, Mae Marsh, Henry Walthall and Ralph Lewis, as well as over three hundred extras for this movie. Filming in the San Fernando Valley began with the battle scenes, which had been rehearsed without gunfire and smoke:

Small groups of actors were placed under the leadership of individuals who would transmit action instructions from Griffith on a tower overlooking the location. Elmer Clifton, Henry Walthall, George Siegmann, Erich von Stroheim, and Andre de Beranger each headed a unit. Each group was rehearsed separately and prepared to execute their movement on a signal from the tower[8]

Amid the noise of battle, instructions to these assistant directors were conveyed by the waving of a series of coloured flags. De Beranger, who had just turned twenty-one when filming got underway, also played the part of Duke Cameron, youngest of the Southern Cameron family’s sons. Elmer Clifton, Henry Walthall and George Siegmann likewise had acting roles as well as assistant director duties.

Griffith inspired his actors with his fervour and enthusiasm, and equally importantly, worked closely with technical staff, who were filming with heavy, hand-cranked Pathé cameras, illuminating outdoor scenes with light bounced off mirrors, and processing each day’s footage in a makeshift laboratory at the studio.[9] In an industry that was trying out new acting and filming techniques almost daily, Griffith attracted those willing to turn a hand to anything.

The Birth of a Nation opened in Los Angeles in February 1915 to acclaim and controversy, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Civil War’s end, and was a huge box office success. By then, movies were the most popular entertainment in the country. Almost every town of any size had a movie theatre; there were nine hundred in New York City alone. While audiences marvelled at the artistry of the film – the acting, the settings and special effects, the gripping narrative – the subject matter was highly controversial. Griffith, himself a Southerner and the son of a Civil War soldier, had based his film on the Reverend Thomas Dixon’s 1905 novel The Clansman: an historical romance of the Ku Klux Klan and play of the same name. The portrayal of negroes and mulattos, in many cases using white actors in blackface make-up, as violent and depraved at worst and simple-minded at best, and the glorification of the Ku Klux Klan, was regarded by many as an endorsement of racial intolerance and the supremacy of whites. Persistent campaigns by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to have the film banned received a boost when the United States finally entered the war in 1917; African American soldiers formed part of the army fighting in France, and the film was condemned for being “damaging to the national unity upon which our success in the war with Germany depends”.[10]

Despite, or perhaps because of, its subject matter, the film raised the profiles of all the actors who played credited roles, including de Beranger’s – even though an error in the original continuity script, which confused the roles of de Beranger and Maxfield Stanley, who played the part of older brother Wade Cameron, still appears in listings and re-releases of the film through to the present day. During 1916 and 1917, de Beranger played a variety of comic and serious roles, ranging from the part of Johan Tonnesen in a film version of Henrik Ibsen’s play Pillars of Society (Fine Arts Film Company,1916), to a gambler and bandit who dies from the plague in Mixed Blood (Universal Film Manufacturing Company, 1916), and professional assassin Automatic Joe in the hilarious Flirting With Fate (Fine Arts Film Company, 1916). Although the last was clearly designed as a vehicle for rising star Douglas Fairbanks, de Beranger stole the picture with his portrayal of a hitman employed to “assassinate” Fairbanks, but who sees the error of his ways and joins the Salvation Army. With one raised eyebrow and a curled upper lip, he snarls such villainous lines as, “Why, I’d croak a whole family for a dollar!”

In 1917, however, the careers of many in Hollywood were interrupted. Up until then, the American film industry had been reaping the benefits of the disruption of the film industries in Europe and England and the closing of many studios there after 1914. Hollywood eventually felt some direct effects of the war. In March of 1917, President Woodrow Wilson had decided to call for a draft of eligible men into the US armed forces. Anyone failing to register would be arrested and imprisoned for a year.[11]

Film quickly became an effective propaganda tool for the US Government. From 1917, the Committee on Public Information mounted a nationalistic “hate the Hun” campaign of posters, pamphlets and rousing speeches in theatres that contributed to a rise in anti-German-American sentiment.[12]

On 5 June, the first draft registration day, over ten million men across the country filed their details. De Beranger registered in Los Angeles, using the name “George Beranger”. He gave his address as “1701 St James Apt, Los Angeles”, and his place of employment, as an actor at Thomas Ince’s Culver City Studios. He gave his correct place and date of birth, but in response to the question “Are you (1) a natural-born citizen, (2) a naturalized citizen, (3) an alien, (4) or have you declared your intention (specify which)?” he answered “lost papers”. De Beranger also claimed exemption from the draft on the grounds that he intended “to join Australian troops”. A month later, in The Moving Picture World’s Roll of Honor column, de Beranger was noted as having “left this week for Australia, his native land, where he will join the army”. Others mentioned in that particular column give the names of specific regiments and training corps they will be joining: the Officers’ Training Corps in Toronto, the Eighth Reserve Regiment of Engineers, the Second Oregon Naval Militia, Colonel Charles A. Doyen’s regiment of United States marines. De Beranger’s entry is curiously vague by comparison, and it is not clear whether he or Culver City Studios placed the story. He was one of many movie industry employees who indicated their willingness to join the war effort, and indeed his filmography lists only two titles for 1918, but there is no record in the Australian National Archives to indicate that de Beranger served with the Australian troops in any capacity. Those “lost papers” might have made it difficult, if not impossible, for him to return to Australia. So one is left to ponder whether he enlisted and served elsewhere – or whether he fabricated his war service, as he had his earlier life.

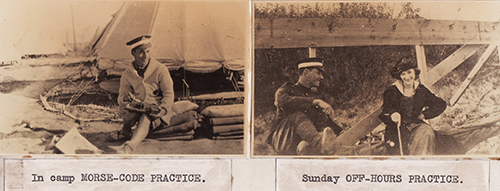

A page of photographs in one of his scrapbooks presents one version of a war service record. The scrapbook page is titled “WORLD-WAR I. Cadet-Pilot (Royal Flying Corps) Long Branch, Ontario”. The central, shadowy photograph of de Beranger in the cockpit of a biplane is captioned “RFC CAN 74665 SQN. 85”.

Andre de Beranger in the cockpit of a biplane (family collection)

Below this are two smaller photographs: one is of de Beranger in shorts, cardigan and peaked cap, seated in front of a tent and with a piece of equipment on his lap, captioned “In camp MORSE-CODE PRACTICE”; the other is of de Beranger, in what appears to be the full uniform of the Royal Flying Corps (Canada), seated next to an unidentified young woman dressed in a stylish velvet jacket and matching hat, and captioned “Sunday OFF-HOURS PRACTICE”. The white band on de Beranger’s cap signifies an enlisted man in training; the puttees he is wearing in the lower right photograph indicate he was not an officer.

Andre de Beranger, in uniform, possibly at Long Branch near Toronto in 1917 (family collection)

I have not been able to ascertain who took these photographs, and for what purpose. Perhaps they were only ever shown to friends and family. De Beranger is not listed in the Canadian Airforce Archives. The Royal Flying Corps was the “over-land air arm” of the British military during most of World War One, and in 1917 the American, British and Canadian governments joined forces to instruct cadets in flying, wireless, air gunnery and photography at several locations in Ontario, including Long Branch near Toronto. It is possible that de Beranger did train as a member of the Signal Corps, and that he arranged to be photographed in the cockpit of a biplane – kitted out in helmet, goggles and leather jacket – without actually taking the aircraft up. Novelist William Faulkner also trained as a cadet pilot near Toronto, and although the war ended before Faulkner had finished his course, he acquired an officer’s dress uniform and a set of wings for the breast pocket, a swagger stick and even a limp. It is unlikely that Faulkner ever flew solo, and he saw no active service, but he encouraged others to believe he had, telling many highly exaggerated or untrue stories of his wartime exploits.[13]

De Beranger’s claimed affiliation with Squadron 85 seems equally farfetched. The squadron was formed in Upavon in Wiltshire, England in mid-1917 and was posted to France in May 1918, where its pilots downed nearly a hundred enemy aircraft. The Royal Flying Corps had a distinguished membership, including flying ace Billy Bishop, scientist and inventor Henry Tizard, cricketer Jack Hobbs, and author of the Biggles books W.E. Johns. In the late 1920s, aviation mogul Howard Hughes was to base his movie Hell’s Angels on the exploits of the Royal Flying Corps, hiring actual World War One aces to fly the stunt planes.

The photograph of de Beranger in a biplane also appears in a folio of studio portraits of his acting roles, which he sent to his older brother Albert Beringer in 1918, presumably as a Christmas gift. The folio appears to have been made professionally; the “Wells Vincent LA” studio shots show George costumed for roles in the films The Birth of a Nation, Those Without Sin (Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company, 1917), Flirting With Fate, The Bride of the Sea (Reliance Film Company, 1915), The Good-Bad Man (Fine Arts Film Company, 1916), and Sandy (Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, 1918). None of these is concerned with flying or the war, and the photograph of de Beranger in a biplane is not a studio portrait. Is he portraying war service as one of a series of acting roles? Perhaps. Or is he engaging in a little family joke, and taking a dig at his brother? Having been classified by the Australian Special Intelligence Bureau as one of the “Enemy Subjects in the Public Service” – although not until May 1918, which seems rather late in the war for the bureau to be engaging in such investigations – Albert Beringer might not have appreciated the humour. Another interpretation of events is that de Beranger was providing his brothers with photographic evidence of the German-born family’s loyalty to British king and country. None of his four brothers in Australia was in active service during the Great War, although the oldest, Adolf “Jim” Beringer, became a member of the citizen forces, having been rejected for active service because of his German birthplace. Albert Beringer, in his deposition for the Australian Special Intelligence Bureau, noted, rather confusingly:

The German language was never spoken in our house. My father never spoke German in the house. My mother understood German. My father and mother sometimes talked in German together, but the children never learnt it and did not understand it. I have 5 brothers all living – none of them spoke German … I have no German friends in Australia … when war broke out, I nearly lost my wife. She was broken down in health. It is for my wife’s sake that I do not enlist. If I had my own way I would not be afraid to enlist at any time. One of my brothers enlisted in the Canadian Army.[14]

Albert Beringer’s older brother Charles also claimed that he had not enlisted because “My wife has been in indifferent health ever since the last child was born. She is very delicate”.[15] Charles Beringer’s deposition reveals quite a detailed account of his younger brother’s “war service”, much of which cannot be verified. Read against de Beranger’s own pictorial record, the former reveals a blend of fact and fiction – or at the very least exaggeration:

My only unmarried brother is in the Royal Flying Corps. His name is George Augustus Beringer. He enlisted in Canada … The last I heard of him he was in Ontario. He went to America and entered the Moving Picture business as an actor. He enlisted before conscription was declared in the United States. He was in a Training School for Officers. I last heard that he was away somewhere fighting. It was in a newspaper cutting that he sent it [sic] to my wife. He was in New York before. I have some snap shots of him in the Flying Corps. I believe that he is away fighting somewhere now. The long delay since hearing from him gives me the impression that he is away fighting.[16]

“Cadet-Pilot de Beranger” would have been in impressive company either among the members of the Royal Flying Corps, Squadron 85, or among those in the movie industry who fabricated or exaggerated war service records. Cole Porter, for example, who did not even register for the 1917 draft and left for Paris two months later, claimed variously to have joined the French Foreign Legion and served in the French Army and to have received the Croix de Guerre – none of which was true. He certainly looked the part of a military man, however, and allegedly had a collection of appropriate uniforms made to suit. What can be verified is that he offered to assist the Duryea Relief Party, founded by American society hostess Nina Larre Smith Duryea, with the distribution of food in Paris during the war.[17]

If indeed de Beranger fabricated – or at least exaggerated – a war service record, then his decision in 1920 to direct a film that was not only anti-war but also critical of the United States Senate’s rejection of President Woodrow Wilson’s plan for a League of Nations, seems a forthright political statement, particularly from a man who did not at the time have American citizenship or even permanent residency status.

Uncle Sam of Freedom Ridge (Harry Levey Productions, 1920) was shot as a full-length, seven-reel feature but only ever released as a short film. It is concerned with a Civil War veteran who is preparing to play the role of “Uncle Sam” in a Red Cross pageant when he hears of the death of his son at the Front. At the end of the war, when the League of Nations Bill fails, “Uncle Sam”, concluding that his son’s death has been in vain, shoots himself with his Civil War pistol. The dialogue includes such provocative speeches as:

We’ve gone back on our friends and let the rest of the world go to hell, so long as we were tucked safe into our little home bed with the Atlantic Ocean pulled over our ears … Anybody who thinks this country has got any ideals worth fighting for is a darn fool.[18]

The film was screened at campaign rallies for the Democratic Party to gain support for the League of Nations. It was rumoured at the time that one of the film’s backers was Bernard Baruch, the head of Wilson’s Trade Board; Wilson himself publicly praised the film.[19]

De Beranger was not to apply for United States citizenship until March 1940, perhaps in response to the outbreak of war and the subsequent tightening of restrictions on overseas travel. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the United States Government also began interning people of German, Italian and Japanese heritage considered to be “enemy aliens”. The application for citizenship was, again, partly a work of fiction. De Beranger gave his full name as “George Augustus Alexandre Beranger”, his “race” as “French-German”, and the date on which he arrived in the United States as 7 April 1922 from London, thereby ignoring ten years’ work in the film industry in New York and Los Angeles dating from 1912, including his first big war role in The Birth of a Nation. The false arrival date hid George’s probably illegal entry into the United States from Canada without official papers – not so much “lost”, as he had claimed in the 1917 military draft, but non-existent.

By the outbreak of World War Two, in September 1939, de Beranger’s film career was all but finished, and he was working as an architectural draftsman with the City of Los Angeles Council. When the Great Depression had hit Hollywood in 1930, several studios closed, and the repercussions were felt across the industry. “Efficiency experts” were brought in by the studio heads and recommended increasing working hours and cutting actors’ salaries by as much as fifty per cent. Freelancers such as de Beranger were the first to be let go. He continued to act in films through the 1930s, although for the most part, ironically in the age of sound, he was cast in uncredited, mainly non-speaking roles: head waiter, apartment manager, florist, hotel clerk, and so forth. His most challenging work from this period might have been another form of “war service”.

Two letters to cinematographer and film historian and archivist Charles G. Clarke, dated November 1942, indicate that de Beranger intended “Leaving for Australia as soon as my papers come from Washington”[20], and that he was keen to sell his silent film library and projector before he departed. Postcards written to one of his Australian nieces show that de Beranger did travel to Sydney late in 1943, possibly after his application for US citizenship was approved in December of that year. By February 1944, he was back in Los Angeles. The reasons for the trip are a mystery, as are the means by which he was able to arrange passage across the Pacific Ocean at such a dangerous time. Many of the records of United States ships carrying troops and civilian passengers to and from theatres of war were destroyed by the United States Department of the Army in 1951.[21] One possible explanation for the trip was that de Beranger had joined the theatre troupe established by British-born Shakespearean actor Maurice Evans, who was commissioned as a captain in the United States Army, and put in charge of the Forces Entertainment Section in the Central Pacific. Evans did some cutting and modernising to produce a play that became known as The GI Hamlet – including removing a third of the text and dressing Hamlet in trousers and a dinner jacket with silver brocade lapels. It was such a success that Evans would stage the play in New York in the late 1940s.[22]

War presented many in Hollywood with reels of footage of action sequences and with the opportunity to act out and to embellish roles. Creative flair, assisted by missing official papers, allowed de Beranger to cut, shape, rewrite and adapt the script of his own life to suit his circumstances. His war service record remains a vague sketch of a role, outlined by a fragmented trail of public records in Australian and American archives. These “war service” performances took place against a backdrop of Hollywood appropriation and opportunism during the Great War, in an industry that thrived on myth-making and illusion.

***

A life characterised by ambiguity ended no less enigmatically. A recluse at the time of his death in 1973, de Beranger was found in his Laguna Beach house south of Los Angeles, behind locked gates and high walls. He had been dead for several days before neighbours noticed mail spilling from the letterbox, and called the police. De Beranger’s body was surrounded by press cuttings, photographs, films and trunks of costumes – mementoes of a life spent partly in disguise.

* André de Beranger, whose real name was George Augustus Beringer, was my husband’s great uncle, which has given me access to family photographs and papers, and intriguingly vague stories about his life and career.

[1] Barbara Duarte, ‘Lagunan Beranger Helped it Happen’, South Coast News, 25 March 1966.

[2] Albert E Smith with Phil A Khoury, Two Reels and a Crank, (New York: Doubleday, 1952), pp. 66-7.

[3] Vachel Lindsay, The Art of the Moving Picture (New York:Macmillan, 1915).

[4] ‘Griffith Builds New Love Story on War’, New York Times, 12 August 1918.

[5] Craig W. Campbell, Reel America and World War I (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.,1985), 96.

[6] Deposition from Albert Charles Valentine Beringer, 15 May 1918, series no A387, item 7912983, National Archives of Australia (NAA), Canberra; Deposition from Charles Joseph Wilfred Beringer, 16 May 1918, series no A387, item 7912984, NAA, Canberra.

[7] Robert M. Henderson, D.W. Griffith: his Life and Work (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), 95.

[8] Henderson, p. 150.

[9] Henderson, p. 152.

[10] National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) national secretary John R. Shillady to Mayor John F. Hylan of New York in February 1918, quoted in Melvyn Stokes, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation: A History of ‘The most controversial motion picture of all time’ (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 228.

[11] ‘World War 1 Draft Registration “Background Information”, Draft Boards Exemptions and Deferrals’, compiled by Raymond H. Banks, http://www.slcl.org (accessed 30 July 2005)

[12] Clayton R Koppes and Gregory D Black, Hollywood Goes to War: How Politics, Profits and Propaganda Shaped World War II Movies (New York: The Free Press/Macmillan, 1987), pp. 48-9.

[13] Richard Gray, The Life of William Faulkner: a Critical Biography, Blackwell, Oxford, 1994, pp. 3-5.

[14] Deposition from Albert Charles Valentine Beringer.

[15] Deposition from Charles Joseph Wilfred Beringer.

[16] Deposition from Charles Joseph Wilfred Beringer.

[17] Charles Schwartz, Cole Porter: a biography (New York: Da Capo Press, 1992), 45-7.

[18] ‘Uncle Sam of Freedom Ridge’, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) unpublished script collection, Margaret Herrick Library, Los Angeles, 39, 41.

[19] New York Times review dated 27 September 1920, http://movies2.nytimes.com (accessed 6 November 2006)

[20] George Beranger to Charles G. Clarke, 21 November 1942 and 26 November 1942, Charles G. Clarke Collection, Margaret Herrick Library, AMPAS, Los Angeles.

[21] ‘1943 Troop Ship Crossings’, http://troopships.pier90.org (accessed 7 September 2006)

[22] ‘Hamlet in Hawaii’, Time, 27 November 1944, http://www.time.com (accessed 4 January 2007)