I’m allowed to go to picture shows,

That is, if nurse is feeling able;

But we only go to Mickey Mouse,

I’m not allowed Clark Gable!

It’s such an imposition

For a girl who’s got ambition

To be an in-between!

(Love Finds Andy Hardy, USA 1938)

In film buff histories, the retrospective compilations produced for awards shows, and in commentary on youth culture, there are two commonly cited histories for teen film. One begins in the 1950s and the other in the 1980s. These stories are in some respects compatible, so that the story about the ’50s focuses on the emergence of the teenager about whom teen film could be made, and to whom it could be sold, and the story about the ’80s focuses instead on the consolidation of “teen film” as a tight singular generic form. In this essay I want to problematise both approaches and contribute to the history they jointly sketch by thinking about what adolescence meant in cinema before the 1950s. But a sense at what is at stake in these competing claims will serve as a useful starting point.

The idea that teen film is an invention of the 1950s—part of the Western emergence of youth culture after the Second World War—is a popular one. Jon Savage puts the argument this way: after the War, “the spread of American-style consumerism, the rise of sociology as an academic discipline and market research as a self-fulfilling prophecy, and sheer demographics turned adolescents into Teenagers.”[1] Thomas Doherty’s Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s is a highly influential example of this argument, analysing an extensive archive of films and the media circulating around them. Doherty claims that the decline of the Hollywood studio system in the 1950s, and related threats to the profitability of cinema, produced a flood of films in which teenagers were central in order to cater to a market newly identified as “teenagers”. He links this to changed economic relations between studios and theatres but also to forces more intimately connected with adolescence, such as post-war suburbanization and the rise of television, which extended the significance of the family home (Doherty, Teenagers and Teenpics 18-19). Amidst these influences, the teenager appeared as both exciting film content and reliable filmgoer.

For Timothy Shary, the 1980s is a renaissance period for teen film largely produced by the multi-screen movie theatre. The multiplex clarified a returning adolescent demographic to whom more and more varied teen films should be addressed. He attributes to this some changing conventions for teen film, including the “complexity of moral choices and personal options” built into the variety of the multiplex (Shary, Teen Movies 55). For Shary’s longer study, Generation Multiplex, the multiplex represents an adolescent quest for social space that recalls the significance of early picture theatres but with more demographic coherence. The techniques by which the film industry exploited this audience also recalls the commodified youth culture Doherty identified in the 1950s but with less demographic coherence and suggests a resurgence that is also a difference at the level of both genre and audience. Despite the usefulness of these different histories I want to supplement them with a focus on earlier films, and earlier modes of distributing and understanding adolescence, and thus suggest the importance of a different kind of continuity underpinning what we now call teen film.

A critical historiography of teen film can find references to films about adolescence before the 1950s in the most influential accounts of teen film as a genre. David Considine’s The Cinema of Adolescence is an important reference point, although many of the films Considine cites are included as precursor texts in Doherty’s Teenagers and Teenpics and in Shary’s genre overviews that emphasise the ’80s.[2] I will draw most heavily on Considine’s text in this essay because he offers a more detailed and longer history. Doherty not only claims that teen film was invented in the 1950s but restricts teen film proper to 1955 – 1959. He summarizes the next forty years of films about adolescence as “a series of postclassical phases retreading, revamping, and reinventing the generic blueprints of the original teenpics of the 1950s.” (Teenagers and Teenpics 190). Shary’s Teen Movies presents a strikingly different history, locating teen film’s infancy in 1895-1948, its early adolescence in 1949-67, its later (rebellious) adolescence in 1968-79, supplemented by a rebirth in 1978-95, and a coda of new teen film speculations in 1994-2004. It is only possible to reconcile Doherty and Shary’s claims if they are talking about different types of teen film, and they centrally differ on the question of whether ’80s teen film is part of the genre or a reply to it. For Shary, teen film in the 1980s became sophisticated and self-conscious while for Doherty this is a “double vision” (Teenagers and Teenpics 196) which betrays these films’ address to adults (as well as teenagers) and makes them not teen film at all.

Although the ’80s is often convincingly represented as a high period for the genre, Considine’s The Cinema of Adolescence, published in 1985, represents the generic shape of teen film as well established before then. Beginning with the recognition that films about adolescence made in the 1930s could remain intelligibly about adolescence for adolescents of the 1970s, Considine emphasises continuity as well as development in the cinema of adolescence. And he stresses the importance of the 1940s and 50s for crystallising a cinematic image of adolescence and discusses teen film in the 1960s and ’70s unaffected by later claims that little teen film appeared in these decades. What we define as teen film depends on very particular historical vantage points, which doesn’t make it at all incoherent.

I do not aim here to resolve these histories into one that is singularly complete, but I want to claim something stronger than that films about adolescence before the 1950s are important precursors to teen film. I think we can approach the history of teen film much as we would a history of fashion—noticing that while, in retrospect, particular styles stand out as characterising periods, even for such a retrospective eye particular conventions and even dramatic changes can become more or less visible over time. But the underpinning idea of fashion is something else, a conceptual apparatus with a longer history wound into other fields. I want to consider here the clear emergence of teen film conventions in pre-1950s films about adolescents: for example the dominant tropes of the high-school film, of the youth-as-party film, of sexual education films, and the alienated force of the adult world so important to films about teen angst.

There are certainly narrative conventions that help define teen film: the youthfulness of central characters; content usually centred on young heterosexuality, frequently with a romance plot; intense age-based peer relationships and conflict either within those relationships or with an older generation; the institutional management of adolescence by families, schools, and other institutions; and coming-of-age plots focused on motifs like virginity, graduation, and the makeover. Engaging with teen film as a genre means thinking about the certainties and questions concerning adolescence represented in these conventions, including the role of teen film in producing and disseminating them. As Adrian Martin argues, “the teen in teen movie is itself a very elastic, bill-of-fare word; it refers not to biological age, but a type, a mode of behaviour, a way of being . . . The teen in teen movie means something more like youth.”[3] Both “youth” and “adolescence” might be more appropriate names for what centres teen film than “teen”. While “teen” names a set of tendencies and expectations rather than an identity mapping onto the years thirteen to nineteen, the concept “teenager” is too narrow to define a genre that is preoccupied with what Martin as well as many scholarly discussions of adolescence call liminality. The fact that we label this genre of films “teen film” is nevertheless significant. “Teen” describes an historical extension of, and limit on, a period of social dependence after puberty. The contradiction between maturity and immaturity that “teen” thus describes is central to teen film, and if the conventional content of teen film can be seen emerging in the decades before the 1950s it is importantly shaped by cinema’s own relation to this contradiction.

“The Little Shopgirls Go to the Movies”: The Age of Cinema

In May 1924, film producer B.P. Schulberg published a short opinion piece in the U.S. magazine Photoplay entitled “Meet the Adolescent Industry: Being an Answer to Some Popular Fallacies”.[4] This was one of many defences of cinema published in the popular press in the 1920s. Schulberg associates film with a mesh of promise and vitality, vulnerability and development, that we still associate with adolescence. He claims here that the contemporary film industry is still maturing and not yet predictable although it has developed unique characteristics. Two years after Schulberg’s essay, film producer, historian and film magazine editor, Terry Ramsaye would claim, “Like all great arts the motion picture has grown up by appeal to the interests of childhood and youth”.[5] But this is evidently not true of arts like painting, theatre and literature to which Ramsaye refers, while it may well be true of cinema.

The modern idea of adolescence is quite different from the markers of majority and ideas about education of earlier periods.[6] Adolescence as an identity crisis bound to both emerging sexuality and training in citizenship was “discovered” in the nineteenth century by new social sciences and new modes of cultural criticism at the same time as experiments with cameras and film were tending towards cinema. Adolescence and cinema were in many respects new industries for the twentieth century, and film’s popularity among youth, and its images of youth, have been an important way of talking about cinema for as long as there has been a cinema industry to talk about.

Public discussion of the threat of mass culture and the vulnerable impressionability of film audiences frequently met up with concerns about adolescence as an especially vulnerable and important life stage. Considine, Doherty, and Shary all generally agree that, as Considine puts it, “From its inception, the cinema has attracted the attention of individuals and groups who believed that it exerted an undesirable influence upon the young.” (2) Schulberg and Ramsaye suggest the importance of ideas about the film audience to early associations between adolescence and film. This was not only the case in the popular press—see the essays by Wilton Barrett and Donald Young in a 1926 issue of Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.[7] Early twentieth-century sociologists and psychologists in the US, Britain, and Europe widely stressed the importance of studying film’s effect on youth.[8] Reference to these debates generally appears in existing scholarship on teen film to account for the historical development of ideas about youth that teen film is presumed to reflect, although Considine gives teen film a little more weight suggesting that it at least responded to the conditions and ideas discussed in sociological and media accounts of adolescence in the 1940s and 50s.[9] For my argument, teen film is not only a crucial contributor to dialogues about the meaning of adolescence it is intrinsic to the dissemination and public institutionalisation of ideas about modern adolescence. Even in the 1910s and 1920s, both cinema and adolescence were already associated with rapid technological and cultural change and diverse authorities opined about what films youth should see and whether or not film could be good for youth.

The modern idea of adolescence underpinning these discussions is often associated with American sociologist G. Stanley Hall. The influence of his model of adolescence as a period of “sturm und drang” (storm and stress) influenced but not defined by puberty—in fact a much longer period of social development—has been recognized by scholarship on teen film.[10] But despite Hall’s reference to a longstanding association of America with youth and Europe with age, it is misleading to think of this adolescence as particularly American, a slippage with far-reaching effects for existing scholarship on teen film. Hall’s pivotal 1904 publication, Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion, and Education,[11] was directly indebted to contemporary European debates about psychological and social development and especially to the work of Sigmund Freud. Hall’s model of adolescence conjoined psychoanalytic and sociological theories, defining adolescence as a personal crisis but also a key social indicator.

After World War I, a range of images of modern life strengthened relatively new presumptions that the problems of adolescence not only revealed but manifested and predicted broader social problems. The two “Middletown Studies”, conducted in 1929 and 1937 respectively by sociologists Robert and Helen Lynd,[12] indicate the increasing centrality to everyday life in America of both the institutions that managed adolescence, like high school, and popular representations of adolescence, including cinema, and new theories about adolescence. These popular representations of adolescence were not just reflected in but also drew on the social sciences, like sociology and psychology, expanding at the same time as the expansion of cinema. Cinema and the social sciences mutually validated each other’s ideas and images of youth, or at least validated the significance of representing youth. That is, the idea of adolescence to which we are now accustomed, and on which teen film today still depends, was produced by interactions between social and cultural theory, public debate, and popular culture.

Psychoanalysis is an important example. In 1909, Hall brought Freud and Carl Jung to lecture in the United States, establishing the influence of psychoanalysis there. For Freud, adolescence was not a passage into adult roles for which childhood had been a training ground. Instead it was a complicated clash between new sexual capacity, already conflicting and often inexpressible fears, ideals, and desires built up and elaborated in childhood, and the new social expectations of immanent adulthood. Psychoanalytic ideas about adolescence shaped new approaches to education and the family across a wide range of experts and institutions. Direct reference to Freud also entered the field of popular cinema—so that Photoplay could describe Alla Nazimova’s Salome (1923) as a “petulant princess with a Freudian complex”,[13] and the Shirley Temple vehicle The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (1947) could joke about an “Oedipal complex”.

Hollywood was not the only film industry influenced by this transnational story about modern adolescence centred on difficulty. In Germany, for example, the dominant studio system in the 1920s and ’30s fed intense debate about the impact of film on society, and on young people in particular. My subtitle, “The Little Shopgirls Go to the Movies”, is taken from a 1927 essay by Siegfried Kracauer in which he uses the newly important social category of working girls to exemplify the problem of the cinema audience.

Watching films the shopgirls watch, Kracauer declares, “According to the cinematic testimony, a human being is a girl who can dance the Charleston well and a boy who knows just as little”.[14] Given that Kracauer also stresses the homogeneity of popular film across the US and Germany, his suggestion that this young audience has a critical perspective remains important to historicising teen film. It points to a complexity in relations between youth in the audience and youth on screen rarely factored into discussions of the genre except as a feature of the generic self-consciousness characterising popular film in the 1980s and ’90s. But if Kracauer’s shopgirls were an adolescent audience, were they watching teen film?

It seems that no one used the label “teen film” before the 1950s “teenpics”—and teenpics and teen film might even refer to different generations of film for and about adolescence. However it is nevertheless useful to ask where these teenpics came from and what modes of cinema for and about adolescence appeared before the 1950s. I propose that there are four necessary conditions for teen film, the first of which is the modern idea of adolescence as personal and social crisis discussed above. But teen film is not defined entirely by what adolescents are represented as being and doing. The second condition for teen film is the incorporation of the modern idea of adolescence into film regulation, without which teen film as we understand it would not exist, and my discussion of teen film conventions and strategies before it is usually thought to begin also offers a beginning point for that history, which I discuss in more detail elsewhere.[15] It is impossible to understand teen film without considering how film censorship and classification systems are premised on the simultaneous definition and protection of youth. In lieu of the more extensive discussion this demands, I will only stress here that systems for managing film production, distribution and consumption always relied on a set of debates about age, maturity, citizenship, literacy, and pedagogy that are not only an important context for teen film but shape its content.[16] These debates and their relation to changing conventions for popular film can be seen in the cinematic and extra-cinematic discourse on adolescence in the early twentieth century.

The public association between film and youth at this time was not only centred on calls for protecting youth from film. In 1926, Arthur Krows’ pessimistic account of cinema argues that film “must meet the level of intelligence of every audience which is to see it” and thus appeal to “the lowest intellectual level”. In support he cites a declaration by “Adolph Zukor, head of the largest film producing, distributing and exhibiting organization in the world” that “the average moviegoer intelligence is that of a fourteen-year-old child”.[17] Terry Ramsaye usefully places this focus on youth in the context of transnational exchange, particularly in the ways American films, after World War I, aimed to compete with international film production.[18] At the time Kracauer, Ramsaye, and Schulberg were writing, cinema’s industrialisation was increasing its emphasis on technological innovation (including the appearance of the “talkies”), and thus refining the ways in which cinema constructed its continued novelty. And the construction of a recognisable array of genres appealing to, and naming, popular tastes and lifestyles was crucial to this development.

This comprises the third condition for teen film—the emergence of targeted film marketing. The idea that teen film is film sold to teens has been given different histories. For Doherty, the teen market was a dramatic development of the ’50s, for Considine it is a more gradual emergence, and for Shary it both appears gradually and is dramatically shifted at particular points, most notably in the ’50s and the ’80s. However, these writers all agree (taking into account Considine’s later introduction to Shary’s Generation Multiplex) that teen film emerges when the film industry actively solicits a youth market through manipulations of genre. The industrialisation of cinema which makes this possible clearly begins earlier than the 1950s. Almost as an aside Shary notes that “one of the reasons the teenage population became more visible” in the early twentieth century “was due to the spread of movie theatres, where young people would congregate” (Teen Movies 2). He gives a great deal more weight to changes in theatre attendance following the emergence of malls and “multiplexes” in the 1970s and ’80s, but the earlier impact of picture theatres as youth venue is equally important.

Film marketing thus overlaps with the final condition for teen film: the translation of modern adolescence into institutions for the analysis and management of adolescence. This refers not only to social theories and public policies or institutions. Censorship and classification systems belong among these institutions, and film made clear contributions to defining what kinds of adolescence were problematic and how they might be managed. For example, the expanding significance and expectation of high school not only gave new coherence to age cohorts, further generationalising culture, but introduced a setting for popular film that was both accessible and dramatic. But the expansion of high school attendance depended on new explanations of its necessity by social and psychological theories about development, family, and culture. That is, it was dramatically advanced by popular film. And when high school was a less common step between childhood and social independence before the 1930s,[19] cinema still found in youth an exciting figure of vulnerability and promise.

Ingénue in the City: Gish, Chaplin, Rooney, Temple

Shary claims that, until the 1930s, with All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), “American cinema depicted young characters on screen in wildly inconsistent ways (and rather infrequently at that)” (Teen Movies 1). However, some important types and tropes for teen film emerged in American cinema between 1910 and 1930. Central to the images of conflict between independence and dependence, rebellion and conformity, maturity and immaturity proliferating in early narrative cinema is an image of youthful innocence known as “the ingénue”. I want to suggest here that the ingénue’s type of innocence is vitally adolescent because it is always on the edge of disappearing: out of date, under threat, or already compromised by the necessities of life and the demands of growing up. And the ambivalence about maturity, about growing up, centred on the ingénue is one of the most important characteristics of teen film as a genre. Its emergence and refinement in pre-1950s film encompasses a wide range of films and figures, some of which seem to be much more like “teen film” character types than others.

Considine lists Mary Pickford first among the pre-talkies icons that shaped the “cinema of adolescence”, noting that she was “barely sixteen at the time she was placed under contract to D.W. Griffith” (2). In the later 1910s, Pickford was a well-known media figure, dubbed “America’s Sweetheart” for her successful representation of a particular image of girlhood. This American girl simultaneously represents a culture under contestation, the virtues of the past, and the promise of a new world. Despite the overt claims of Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915), this image of girlhood was not confined to the US but appears wherever cinema engages with a clash between cultural identity and modernisation: for example in Alfred Hitchcock’s early British films and in Charles Chauvel’s outback Australian films. But Pickford’s girl iconically opposed the corrupting influences of modern life and to accomplish this she was held—rather like Lewis Carroll’s Alice—just on the edge of adolescence. Pickford’s famous long curls symbolised both her little-girlhood and an idealisation of the past, referring to a nineteenth-century convention for girls tying up their long hair as a sign of entering womanhood, and it was matched by costumes with similar connotations. This image of girlish virtue was attached to Pickford even as the fashions for clothing and hair around her changed and she herself aged.[20] Across the field of films and extra-cinematic texts in which she appeared the Pickford girl always raised questions about sophistication and maturity.

The problem of a modern world which leaves no room for innocence becomes in such films a drama about the inevitable tragedy of growing up. The exemplary female ingénue of this period is Lillian Gish, filmed by Griffith as a beautiful victim. Birth of a Nation, the most famous Griffith-Gish collaboration, intersects male and female ingénue narratives by combining boys going off to war with girls who find themselves at the mercy of corrupt men. But I want to focus instead on the melodrama Broken Blossoms (1919), in which Gish plays Lucy Burrows, an innocent who always knows too much about the world. Twelve-year-old Lucy is routinely beaten by her father, but she knows that she must lie about this. As with the Pickford girls and Birth of a Nation’s Elsie Stoneman, Lucy’s long unbound hair represents both her innocence and her age. Twelve is an important age for stories about adolescence, taking up English Common Law standards defining minority as pre-pubescent that were displaced by laws on education, child labour, and sexual consent that confirmed a distinction between physical and social maturity. Lucy not only equates childhood and innocence but at the same works as a tragic figure because she is positioned at the furthermost limit of childhood innocence, where it seems to have become untenable.

Physically mature and theoretically capable of leaving her father, Lucy is constrained by family, church, and money. Her choices, at the centre of this story, are to stay with her father, become a prostitute, or find a man to protect her. The evident sexualisation of her alternatives is furthered by elements that became important to later teen film: a makeover plot in which new clothes offer a new outlook that reveals her intrinsic beauty; and a romance narrative centred on the desirability of innocence. It’s Lucy’s innocence that her would-be lover, Cheng Huan, admires. Although much older, Cheng is also framed as an ingénue. The film opens with his departure from China to the West, where he has high hopes for dialogue between cultures and even for converting the West to Buddhism. But the London where we next see Cheng is seedy, violent, and unjust, and has relegated him to opium dens and despised service. Lucy defines it by opposition—her faintly hopeful earnestness against its slovenly intemperance. But Cheng too clings to idealism in his upstairs rooms—a world of secret orientalist beauty that explains his desire to save Lucy.

For Gish’s famous on-screen presence, youth was crucial to the types of fear, love, and disgust she was displayed as feeling. Griffith explained her type of beauty as immortal and spiritual, defined against female sexual maturity where “years show their stamp too clearly.”[21] But on-screen youth wasn’t only a staving-off of death and redundancy. The Griffith-Gish films emphasise the problem of what adolescents can do and what they cannot control at the border of the private and the public. In both these respects I want to juxtapose these stories of innocence with a set of films that do not centre on teenage characters and which it might seem tendentious to claim as teen films: the ingénue-in-the-city films of Charlie Chaplin. I want to suggest Chaplin provides an interesting limit case for an argument that the cinematic adolescent central to teen film is defined less by age than by a slippery social position that juxtaposes promise and powerlessness.

Chaplin’s “little tramp” character is neither young nor old but a figure of entwined innocence and experience. As a character named in credits (later defined by his iconic costume of bowler hat, shabby black suit, and cane) the tramp appears in Chaplin’s second film, Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914), where he plays a game with the camera and the audience, repeatedly walking into frame as if by accident. Across dozens of films, Chaplin’s tramp plays innocent knowingfulness against the corrupt sophistication of the city. His agelessness is central to this performance so that his tricks and manipulations, as much as his clumsiness and confusion, seem innocent rather than malicious or idiotic. In films like Modern Times (1936), he occupies the adult world like a child in a huge doll’s house.

In The Kid (1921), the tramp is played against type as a parent figure to a street urchin. He is both a criminal and yet too innocent to withstand the worldly machinations of characters with less capacity to love. Promotion for The Kid emphasised a parallel between “tramp” and “kid”, posing them to emphasise their matched perspectives on the world: looking back over their ludicrously baggy trousers with twin melancholy expressions, or peering wide-eyed around a corner under ill-fitting hats, their fingers grasping the same wall. The tramp’s comic failings are generically failure at adult roles—to hold down a job, to be a provider, or to find a romantic partner. If adult roles escape him they also oppress him. Any exception is almost unbelievable good fortune, as in the close of The Kid where, in a sequence that could be a dream, the tramp is not only welcomed into the house where the kid has been restored to his long-lost mother but is helped to that reunion by the previously hostile police. The tramp is necessarily mobile, permanently dissatisfied, and always making-do. But he is as tolerant as he is cynical, and the tramp’s triumph lies in his insistent innocence in the face of knowing exactly how the world works. In never growing up precisely because he knows the score. Without ever playing an adolescent, Chaplin was the Holden Caulfield of his time.

In Hollywood before 1950, growing up on screen was not only a matter of the development of characters in particular films but of narrating stardom across sequences of films. In The Kid, the kid is played by Jackie Coogan in a precursor to an array of “tough kid on the street” films in which the protagonists ranged from small children to young adults in their twenties. Their relation to proper adult roles and institutions with social authority unites them, often in angry protest, establishing a position eventually labelled “the juvenile delinquent” (JD). The JD film is often associated with the 1950s, and its later influence in teen film generally referenced back to that period, but in fact the JD figure emerged gradually across the previous decades. Considine’s history rightly emphasizes not only key texts like Boys Town (1938) and City Across the River (1949), but also the broader sub-generic conventions established by popular film series about kids on the streets (165-67; 178-79).

Drawing on the movie Dead End (1937), “The Dead End Kids” is a label uniting a range of popular films about juvenile gangs. They focused on the question of what brought “kids” to crime and what might keep them out of it. As in Dead End, where Humphrey Bogart plays the tellingly nicknamed “Baby Face”, older characters often replicated or openly reflected on the Kids’ narrative about trying to escape a life of crime. These films gave popular form to what would become teen film’s key narratives about rebellion and authority but equally its less discussed narratives about class and destiny. The Kids belong to “Code” Hollywood, when new moral guidelines meant that judgment and punishment were built into film representations of villainy. The Production Code has been widely discussed in film history (see Doherty, Pre-Code), but it is also vitally important to the emergence of teen film. Commencing in 1930 and given more authority in 1934 with the establishment of the Production Code Authority (PCA), the Code not only responded to the putative effects of film on youth but also encouraged particular stories about and images of youth. The JD raised questions about environment, responsibility, and socialisation that linked film to “realistic” current issues and films centred on the JD could thus satisfy the demand for pedagogy and punishment while allowing opportunities for pathos and debate.

Institutions that might protect adolescents from delinquency appeared in film alongside public sphere discourse along the same lines. In a 1944 Saturday Evening Post feature, for example, delinquency is understood as much through narrative film as through the social programs being reported. The article refers to the Dead End Kids and directly cites Boys Town. One anti-JD strategy is referred to as “the Boys’ Town plan” [22] [23] the representation of delinquency and its management in cinema had clearly expanded.

Jimmy Cooper mixed such street kid roles with adolescent romantic comedies and with coming-of-age films like Paramount’s Henry Aldrich series. Considine positions this series as a direct reply to the success of the MGM Andy Hardy films starring Mickey Rooney (43-44). Rooney’s own image was built through a mix of youthful comedic and dramatic roles (including Boys Town, in which he played the JD junior lead). But the Hardy films came to underpin his image. There were eighteen Hardy films between 1937 and 1946, followed by a relatively unsuccessful sequel with an adult Andy in 1958. A representative still from Love Finds Andy Hardy is reproduced as Figure 1. Like many other critics, Considine sees this series as a “distortion of reality that both confirms and denies, heeds and ignores, the changing nature of the American family” (28), but the Hardy films belong to a contradictory field of stories about adolescence at the time.

Despite the reassuring predictability of the plots centred on him, Andy is an engaging character because his terror in the face of judgment is tempered by earnestness and enthusiasm. He established a type for film and television adolescents which remains recognisable today. Love Finds Andy Hardy typically begins by demonstrating the reasonable authoritativeness of Andy’s father, Judge Hardy. But it centres on Andy’s quest to improve his social standing by negotiating relationships with three different girls who want to be his girlfriend. The gains he might make from each must be juggled with urgent hormonal impulses always in conflict with the virtue of girls and, at the same time, his father’s expectations. Fifteen-year-old Andy is very sure about the kind of man he should be in ways that contrast sharply with the heroes of many later teen films, but he is entirely unsure how to achieve this goal. In Life Begins for Andy Hardy (1941), Andy graduates from high school and moves to the city, but the “begins” in the title is indicative for the series as a whole. Andy is forever waiting for things to be real for him—for a real car, real job, real love.

The epigraph to this essay is from a song sung by one of Andy’s girls in Love Finds Andy Hardy: the young Betsy Booth (Judy Garland, Figure 1). Georgeanne Scheiner opens her book on pre-1950 movies about girls with the same lyric (1). Betsy’s adolescence is more clearly marked by clothes and admiration than is Andy’s, but both understand adolescence as a place of potential in which one strives to attain an image of adult sophistication hoping that respect will follow. Betsy’s “In Between” represents the difficulties of adolescence as progress through popular culture (Mickey Mouse vs Clark Gable), socialisation (toys vs boys), and chronological age (she yearns to be 16, the age of consent). While no special youth culture between child and adult is here identified with this in-between-ness, Andy’s stories are punctuated with activities, like the swimming pool, the school dance, and the soda shop, that seem particular to youth and which continue as key tropes in teen film. And generational difference and cultural change are central to the Hardy series, with The Courtship of Andy Hardy (1942) even implying that Andy’s parents had similar conflicts with their own parents.

Placing Shirley Temple in this history of teen film might initially seem almost as problematic as including Chaplin, given that she is most famous for her roles as a small girl, styled in extravagant curls and baby doll dresses. But not only did Temple later play adolescent roles, her “little girl” is another version of the ingénue trope. She questions what maturity means. The Temple girl is so excessively knowing that her innocence is a comic question rather than a banal fact. At first, Temple’s career responded directly to Pickford’s girl-played-by-a-woman, unfaithfully remaking a number of Pickford films as musical comedies. While Temple was a different kind of child-adult than Pickford, how much little girls should do or know remained central to her characters. Like Chaplin’s tramp, the Temple girl makes a virtue of suffering under institutions. She is frequently pressed into roles inappropriate to her years due to accident or neglect. The danger this exposes her to generally remains implicit, however, because unlike Gish’s girls a “little princess” film demands happy closure.

In Stowaway (1936), Temple plays Ching Ching, an orphan raised in China, who is sent away from her foster home to avoid a dangerous raid and inadvertently ends up on a ship going to America. Comparing this story about intercultural encounters and youthful innocence to Broken Blossoms throws up many differences in style, narrative, and performance but it leaves one crucial similarity. These girls are wise beyond their years because they have suffered—as Tommy (Robert Young) says, Ching Ching speaks like an adult. The advice Ching Ching repeatedly offers is not childhood instinct but the careful rehearsal of learned pseudo-Confucian homilies. And if she is a natural rather than trained entertainer in Stowaway, the vignettes in which she sings and dances are also knowing tableaux that insistently raise questions about training and environment.

Rooney made a successful transition to adolescent star which was unavailable to Pickford and which Temple failed to make. Shary speculates that “Americans seemed far more prepared to watch a boy grow into manhood than to watch a girl grow beyond adolescence.” (Teen Movies 8 ) But Garland’s role in the Hardy series makes it clear that a girl could parallel Andy’s always abortive development—making the same tentative moves towards adulthood without ever being entirely transformed. Considering Temple’s relative lack of success as an adolescent actor, Shary suggests “teens of the late 1940s were quite likely eager to move beyond their parents’ notions of youth, which Temple had represented to them” (Teen Movies 9). But Temple did have some success in “bobby-soxer” movies like Kiss and Tell (1945) and The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer. These films contain highly recognisable teen film characterisation and plot devices, including misrepresentation of sexual reputation, the new kid at high school, and teenage endeavours to construct an image of maturity through both sex and personal style. Such films, and Figure 1, foreground a distinctive 1940s youth culture through clothing, music, language, and practices like basketball, cheerleading, “malt shops”, and jukeboxes. The bobby-soxer, as Scheiner puts it, “had her own language, mannerisms, fashions, concerns, and style” (6), and on screen this teenage world is construed as alien to any parent culture.[24]

The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer parodies teenage aspirations while stressing the appropriateness of youth culture. The moral thrust of the film is about acting one’s age but the film centres on ambivalence over this necessity. Older sister Margaret (Myrna Loy) is a judge who doesn’t realise she’s missing out on love while still a young woman, Dick (Cary Grant) is a playboy who is unaware what kind of woman he really wants, and Temple’s Susan doesn’t realise she is still a child. Susan is moody, dreamy, and desperate to be an adult even while she sulks in her bedroom. Her characterisation stresses the idealism and ennui of adolescence widely associated with much later films, and also the importance of sexual development in comparison to other forms of education (although Susan is a high-achieving and articulate student). This film more explicitly than many around it also presents a theory of adolescence through references to psychoanalytic and other developmental theories supplemented by the visualisation of fantasy. Thus it is with reference to both bobby-soxer and JD films that Considine can argue that adolescence emerged in the 1940s “as a fact and phase recognized by the motion picture industry” (33; 42). But if Gish and Pickford did not make teen film in the same way as Rooney and teenage Temple, it remains important to ask what marks the transition between Broken Blossoms and The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer.

“The Orchidaceous Clara Bow”: The Plastic Age and the Flapper Star

If Temple and Rooney’s adolescent roles were teen roles, Doherty’s taxonomy of teenpics would call them “clean teens” (Teenagers and Teenpics 145-86). Indeed, in the heyday of the Production Code, adolescence was dominated by a stark opposition between delinquents and clean teens that has had a lasting effect on teen film. Both figures worked by presenting adolescence as a problem of what one could and should do and both were in effect produced by the Code itself. This is an under-emphasised element of Code Hollywood conventions—while Doherty pays attention to “juvenile” figures of social upheaval (Pre-Code 6, 90-91, 156-57, 167-69) his own histories suggest little important common ground between these and other figures of youth. Images of wild youth on screen had far less to do with empirically new patterns of social delinquency than with changing film genres and cinematic strategies. The Code forced US film, and encouraged other film industries, to search for ways to represent transgression indirectly, producing strategies like the shadows of film noir and the new filmic uses for the uncertainty, vulnerability, and impulsiveness of adolescence. The clean-ness of many successful 1940s screen teens can distract us from the diversity of youthful roles before the ’50s and make it worth looking back at the scandalous films which inspired the Code.

While the pre-Code roles of Jean Harlow are never discussed as teen films they were crucially girl roles, dominated by the question of who Harlow’s characters would become. Harlow was just nineteen when she played the controversial Helen in Hell’s Angels (1930), declaring: “I wanna be free. I wanna be gay and have fun. Life’s short. And I wanna live while I’m alive.” If, as Considine stresses, there were not many girl JD films during the first period of the subgenre’s popularity (172-73; 182-83), this is partly because girls’ risky behaviour was linked to sexual reputation rather than crime. We could compare Harlow in Hell’s Angels to Clara Bow’s nineteen-year old performance as Orchid in Grit (1924). Orchid is a street gang-member trying to go straight, but the reference points for her morality are principally sexual rather than criminal. It matters to the sexual dimension of bad girls rather than bad boys in pre-Code films that Grit was written by “jazz age” chronicler, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and both Grit and Hell’s Angels are a hybrid of gang and flapper film genres.

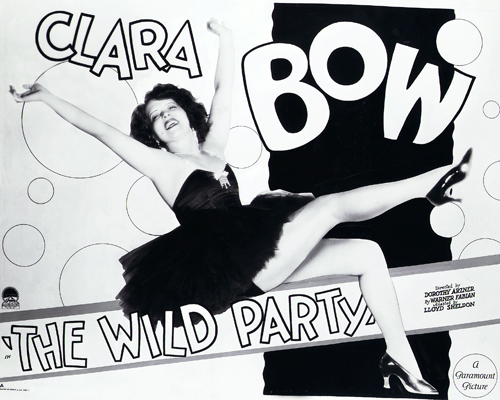

As a popular pre-Code genre that combined representation of current social issues and a focus on adolescent identity formation, the flapper film is an excellent test case for the claim that there were teen films before the Code.[25] These films, exemplified in the promotional image for The Wild Party (1929) reproduced as Figure 2, centred on the shockingly unregulated behaviour of modern girls. They shared an ethos opposed to the ingénue and efficiently summarised as pleasure by the character Diana Medford (Joan Crawford), heroine of the flapper series beginning with Our Dancing Daughters (1928). “It feels so good,” Diana says, “just to be alive”. Film perfected rather than invented the flapper image, which was established by the press and popular fiction as uniting ambivalence about contemporary life, spectacular generational difference, and disrupted gender norms. Colleen Moore had some of the most famous flapper film roles, including in Flaming Youth (1923). But Flaming Youth was based on a Warner Fabian novel that itself drew on media panic over “flappers”, tying them to new public perceptions of changing gender norms.

The heroine of flapper films often first appears to be a rebel and is discovered to be an ingénue; or else she understands herself as a rebel only to discover her desire to conform. The ambivalent relationship between rebellion and conformity so important to teen film is clearly established in these films as a youthful characteristic if not a necessary psycho-social developmental stage. As Figure 2 indicates, publicity around Bow stressed her blend of vulnerability and action. In 1930, Leonard Hall described her as “[d]ashing, alluring and cinematically untamed, she was flaming youth incarnate—the personification of post-war flapperhood, bewitching, alluring and running hog-wild. All the old taboos and thou-shalt-nots were knocked dead by the new freedom for adolescents”.[26]

The Bow vehicle It (1927) was one of several film adaptations of the sensational romance novels of Elinor Glyn.[27] As “It”, Bow was a particularly adolescent version of feminine glamour and as explicitly commodified as any teen film hit. As advertorials put it:

IT can move mountains and cash registers. IT is sought, sought, sought. Students of IT have found manifestations most frequently in members of the feminine sex, sized about five feet two, red-headed and aged eighteen.[28]

In uniting flapper films as teen films I disagree with Scheiner’s distinction between college-aged flapper roles and films of this time about school-aged youth (30). The lack of clear distinction between teenagers and young adults in the flapper films becomes, in fact, a recurring feature of teen film. To consider this claim I will focus on The Plastic Age (1925), a Schulberg production directed by Wesley Ruggles and starring Clara Bow.

Hugh (Donald Keith) is a high school athletic star, beloved and trusted by his parents, who send him off to college with high expectations. Hugh’s college peers lack the serious application he is used to, and he is soon dragged into fraternity hazing and meets the popular party girl Cynthia (Clara Bow). Hugh is instantly in love and Cynthia is touched by his innocent sincerity. They commence an affair which leads Hugh away from his commitments to sports and study. His disappointed father disowns him. After they narrowly escape arrest during a raid on a nightclub where Hugh has wound up fighting friend-turned-rival Carl (Gilbert Roland), Cynthia decides to push Hugh away for his own good. He regains his success on and off field whilst, unbeknownst to him, Cynthia pines for him at a distance. They are finally reunited as Hugh is leaving college for the last time, when Carl reveals Cynthia’s constancy and newfound virtue.

Though Bow has more respected and more famous films, The Plastic Age exemplifies how flapper films developed the concerns of later teen film. It opens with a dedication addressing contemporary public life which became a minor refrain for teen film while it became obsolete in other genres:

Dedicated to the Youth of the World—whether in cloistered college halls, or in the greater University of Life.

To the Plastic Age of Youth, the first long pair of pants is second only to—the thrill of going to college.

From extant reviews and promotion we know that Bow’s The Wild Party (Figure 2), based on another popular Fabian novel, has another familiarly teen-film plot, centred on girls competing for their teacher’s romantic attention. But The Plastic Age offers a narrative which is as much about the boy as the girl, even if Bow shines in comparison to Keith. Hugh’s story about parental expectations and the conflict between reputation, aspiration, and temptation in an athletic star’s life are as relevant to later films as the moral makeover of Cynthia.

For contemporary teen film, Hugh might be a “jock” and, typically, the emphasis is on his personal rather than sporting development. He begins the film sure he is already a man, while his mother in particular feels otherwise. She urges his father to give Hugh advice about girls before he leaves, foreclosing, it seems, on the pregnancy narrative common in flapper films. But the sex education Hugh’s father can offer doesn’t equip him to deal with Cynthia. For contemporary teen film, Hugh might also be a “geek”. He is teased by other boys for being studious, clumsy, and a “great gink”, and for having the wrong underwear. Either way, Hugh is the good boy counterpoint to the smooth girl-catching sophistication of his roommate Carl. Hugh’s confrontations with new ideas of manliness are central to his college experience; he is an ingénue with inadequate skills for coping with college life despite the value credited to his virtuous self-deprecation and romantic good intentions.

Sex and drug use are often implied in the flapper films. In The Plastic Age, smoking and drinking are represented as commonplace parts of college life, despite (or because of) the reigning US Prohibition laws (from 1920-1933), and other illegal drug use is also apparently common. There’s a typical reference to marijuana in one dance hall scene as characters come and go from behind a heavy curtain amid clouds of smoke and the direction and camera work imply the effects of drugs. This curtain also represents and conceals sex as kissing and fondling clearly progress to something more affecting off-screen. It’s important to the flapper film that such risky behaviour is entwined with the dominant expectations of adolescence—school or college, career choice, and developing independence and romantic attachments—and in this way the flapper film contributed to debates that led to the Code.

Cynthia is as wild as any boy, and if her sexiness is fun-loving it is also somewhat jaded. Her makeover plot is centred on falling in love. A key difference between flapper films and girl-centred teen film in later decades is that they might feasibly end in marriage, which was gradually removed from films about adolescence while romance stayed central. Plots where girls play central roles very often close with a romantic couple, but teen film belongs to the extension of adolescent development and thus delay of the full social maturity with which marriage is associated. The Plastic Age closes with a couple who have suffered in order to be together in the right way, but marriage is only a possible future. Extracting marriage from the girl-centred film not only reflects changed models of girlhood but also a new generic distinction between adolescent and adult romance on screen.

Thus The Plastic Age foreshadows the high school film. While it shares many narratives and motifs with later college films, the mesh of close monitoring by parents and institutions with experiments in identity and transgression is especially apparent in high school films. And many recognisable high school film types and tableaux appear. Alongside the good and bad boys and girls we find the cool teacher who understands what kids are really like; the fat boy and the clever boy as the butt of popular boys’ taunts; love triangles that depend on reputation for girls and prowess for boys; and the recurring motifs of the locker room and the big dance. A stress on the gap between institutional expectations and the real life of adolescents in those institutions makes most college films seamless extensions of the high school film.

Like Pickford and Temple, Bow’s celebrity was dominated by an unresolvable story about growing up.[29] It was not only, as critics like Scheiner suggest, that her image stayed trapped in girlhood (51). Bow fell from stardom in the wake of “the talkies”, and yet talking itself was also not the whole problem. As distinct from the players of Pickford’s era, the flapper stars were not “little girls”. The characters they played tended to vivacious, impulsive sexuality which extended into their public images as stars—on and off screen they were exciting party girls. But they were also supposed to represent a self-interrogating “everygirl”. The ideal adolescent Bow played had to be widely accessible, and both the public scandals that marked her career and her strong Brooklyn accent made her a too particular kind of girl. The public scandals around Bow exemplify the culture in which the Code appeared,[30] but Bow also exemplifies how the teen-star commodity seeks contradictory effects from youth. As partial synonyms for “teenager”, the terms flapper and bobby-soxer point to a nexus of adolescence, commodity culture, and governance. They are simultaneously social problems and fashionable styles. Commodified teen film stars, as much as the characters they play, dramatise the problem of maturity through the circular trap of youthful glamour and public dramatisations of a clash between innocence and experience.

The ideas about adolescence to which these earliest teen films referred were not exclusively American. But Hollywood’s establishment as the premier film industry in the world at this time is not incidental to a history of teen film. Its dominance grounds the strong association between teen film and American-ness which now warrants closer interrogation. That is the work of a larger project, but closer consideration of teen film’s early forms and gradual emergence will enable a better understanding of Hollywood’s contribution to the genre. Teen film emerged at a time when the cinema refined its products into a field distinguished by genres. These genres were structures for appealing to expectations, producing novelty, and repeating success, but contra Doherty’s important and generally insightful archival work on the production of 1950s teenpics, this is not more true of teen film across its history than many other genres. A broader historical and cultural range in discussing teen film has much to offer. And while the popular and scholarly histories of teen film that emphasise the 1950s or the 1980s are compelling for good reason, they make more sense in relation to one another, and are also individually illuminated, following attention to teen film’s own long adolescence.

Works Cited

Barrett, Wilton A. “The Work of The National Board of Review.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 128 (1926): 175-186.

“Clara Bow”, Photoplay, June 1925.

Considine, David M. The Cinema of Adolescence. New York, McFarland, 1985.

Doherty, Thomas. Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality and Insurrection in American Cinema, 1930-1934. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Doherty, Thomas. Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s, 2nd edition. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002.

Doherty, Thomas. Hollywood’s Censor: Joseph I. Breen and the Production Code Administration. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007.

Driscoll, Catherine. Teen Film: A Critical Introduction. London: Berg, 2011.

Driscoll, Catherine. Modernist Cultural Studies. Miami: University Press of Florida, 2010.

Hall, G. Stanley. Adolescence: Its Psychology and its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion, and Education. 2 vols. New York: Appleton, 1904, 1911.

Hall, Leonard. “What About Clara Bow? Will the Immortal Flapper Learn Self-discipline? Or is she Fated to Dance Her Way to Oblivion?” The Talkies; Articles and Illustrations from Photoplay Magazine, 1928–1940, edited by R. Griffith, 20, 275. New York: Dover Publications, 1971. Originally published in Photoplay 1930.

“How They Do Grow Up”, Photoplay, October 1923.

Hurlock, Elizabeth. Adolescent Development, 2nd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1955.

“Interview with D.W. Griffith” Photoplay, August 1923.

Kracauer, Siegfried. The Mass Ornament, translated by T. Y. Levin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Krows, Arthur E., “Literature and the Motion Picture,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 128 (1926): 70-73.

Lewis, Jon Hollywood V. Hard Core: How the struggle over censorship created the modern film industry. New York: New York University Press, 2000.

Lynd, Robert S. and Helen M. Lynd. Middletown: A Study in American Culture. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co, 1929.

Lynd, Robert S. and Helen M. Lynd. Middletown in Transition: A Study in Cultural Conflicts. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co, 1982. Originally published in 1935.

Martin, Adrian. “Teen Movies: The Forgetting of Wisdom,” Phantasms. Ringwood, Vic.: McPhee Gribble, 1994, 63-69.

Mitchell, Alice Miller. Children and Movies. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1929.

“The Quest for It”, Photoplay, April 1927.

Ramsaye, Terry. A Million and One Nights: A History of the Motion Picture Through 1925. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1926.

Review of Salome directed by Alla Nazimova, Photoplay, August 1922,.

Savage, Jon. Teenage: The Creation of Youth Culture. London, Viking, 2007.

Scheiner, Georgeanne. Signifying Female Adolescence: film representations and fans, 1920-1950. New York: Praeger, 2000.

Schrum, Kelly. Some Wore Bobby Sox: The Emergence of Teenage Girls’ Culture, 1920-1945. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Schulberg, B. P. “Meet the Adolescent Industry: Being an Answer to Some Popular Fallacies,” Photoplay, May 1924.

Shary, Timothy. Generation Multiplex: The Image of Youth in Contemporary American Cinema. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002.

Shary, Timothy. Teen Movies: American Youth on Screen. New York: Wallflower Press, 2005.

Storck, Henri. The Entertainment Film for Juvenile Audiences. Paris: UNESCO, 1950.

“They Showed How Juvenile Delinquency Can Be Licked,” Saturday Evening Post, 24 April 1944.

Wall, W. D. and W. A. Simson, “The Emotional Responses of Adolescent Groups to Certain Films.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 20 (1950): 153–63.

Young, Donald. “Social Standards and the Motion Picture.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 128 (1926): 146-150.

Zeitz, Joshua. Flapper: A Madcap Story of Sex, Style, Celebrity, and the Women Who Made America Modern. London: Crown, 2006.

Notes

[1] Jon Savage, Teenage: The Creation of Youth Culture. (London: Viking, 2007), 18.

[2] David M. Considine, The Cinema of Adolescence (New York: McFarland, 1985). Thomas Doherty, Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s, 2nd edition (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002). Timothy Shary, Generation Multiplex: The Image of Youth in Contemporary American Cinema (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002); Teen Movies: American Youth on Screen (New York: Wallflower Press, 2005). Further references to Considine, Doherty’s Teenagers and Teenpics and Shary’s Teen Movies appear as page numbers in brackets.

[3] Martin, Adrian. “Teen Movies: The Forgetting of Wisdom,” Phantasms. (Ringwood, Vic.: McPhee Gribble, 1994), 66-67.

[4] Schulberg, B. P. “Meet the Adolescent Industry: Being an Answer to Some Popular Fallacies,” Photoplay, May 1924, 98.

[5] Terry Ramsaye, A Million and One Nights: A History of the Motion Picture Through 1925 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1926), xi.

[6] Catherine Driscoll, Modernist Cultural Studies (Miami: University Press of Florida, 2010), 21-65.

[7] Wilton A. Barrett, “The Work of The National Board of Review,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 128 (1926); Donald Young, “Social Standards and the Motion Picture,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 128 (1926)

[8] Elizabeth Hurlock’s overview of such research was published in 1949 and updated and expanded in 1955. Elizabeth Hurlock, Adolescent Development, 2nd edn. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1955). U.S. examples include Alice Miller Mitchell, Children and Movies (Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1929); in Britain, see W. D. Wall and W. A. Simson, “The Emotional Responses of Adolescent Groups to Certain Films,” British Journal of Educational Psychology 20, 1950; and in Europe see Henri Storck, The Entertainment Film for Juvenile Audiences (Paris: UNESCO, 1950).

[9] Doherty uses Hall, the Lynds, and general reference to sociology of youth to account for the American-ness of adolescence (Teenagers and Teenpics, 32-42). See also Georgeanne Scheiner, Signifying Female Adolescence: film representations and fans, 1920-1950 (New York: Praeger, 2000), 29-31. Further references to Scheiner’s text appear as page numbers in brackets.

[10] Both Shary and Doherty acknowledge Hall’s influence. Doherty notes that Hall “had condemned the nineteenth-century economic environment as ‘one where our young people leap rather than grow into maturity,’ arguing that ‘youth needs repose, leisure, art, legends, romance, and, in a word, humanity, if it is to enter the world of man well equipped for man’s highest work in the world’” (Doherty, Teenagers and Teenpics, 41).

[11] G. Stanley Hall, Adolescence: Its Psychology and its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion, and Education, 2 vols (New York: Appleton, 1904, 1911).

[12] Robert S. Lynd and Helen M. Lynd, Middletown: A Study in American Culture (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co, 1929); Middletown in Transition: A Study in Cultural Conflicts (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co, 1982).

[13] Review of Salome directed by Alla Nazimova, Photoplay, August 1922, 67.

[14] Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995), 301.

[15] Catherine Driscoll, Teen Film: A Critical Introduction (London: Berg, 2011).

[16] See Jon Lewis, Hollywood V. Hard Core: How the struggle over censorship created the modern film industry (New York: New York University Press, 2000); and Thomas Doherty, Hollywood’s Censor: Joseph I. Breen and the Production Code Administration (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007). Doherty and Lewis both follow books on teen film with books on the history of U.S. film censorship and classification, although unfortunately without directly considering the relations between these subjects.

[17] Arthur E. Krows, “Literature and the Motion Picture,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 128 (1926), 72.

[18] Ramsaye, 324; 381.

[19] Driscoll, Teen Film, 34-35.

[20] In 1922, when Pickford was 29, Photoplay captioned a studio portrait: “The world has been waiting for Mary Pickford to grow up. But Mary says she will continue to leave the maturer roles to others. When we look at her here we think she’s right”. But the following year the same magazine declared: “the time has come when Mary must put up her curls, because life has made a woman of her. Womanliness is in the thoughts behind her eyes and it radiates outward. It is in the new lines of her body. In the warm understanding, the gentle curve of her lips. . . . Wifehood, charity for the world, the love of a man, the desire for motherhood, the awakening of the girl-mind,–they’re all there. And no curls, no slim, bare legs, no reproduction of child-actions can mask them any longer.” “How They Do Grow Up”, Photoplay, October 1923, 40.

[21] “Interview with D.W. Griffith” Photoplay, August 1923, 35.

[22] “They Showed How Juvenile Delinquency Can Be Licked,” Saturday Evening Post, 24 April 1944, 96.

[23] “They Showed How,” 70.

[24] For detailed discussion of the emergence of the girl culture focused on the “bobby-soxer” figure see Kelly Schrum, Some Wore Bobby Sox: The Emergence of Teenage Girls’ Culture, 1920-1945 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

[25] Several origins for the term have been suggested but “flapper” is always a label for femininity challenging codes for both appearance and behaviour. The flapper was opposed to corsets and associated with short hair, shorter skirts, and newly active lives characterised by jobs, cars, smoking, drinking, and dancing. See Joshua Zeitz, Flapper: A Madcap Story of Sex, Style, Celebrity, and the Women Who Made America Modern (London: Crown, 2006).

[26] Leonard Hall, “What About Clara Bow? Will the Immortal Flapper Learn Self-discipline? Or is she Fated to Dance Her Way to Oblivion?” in The Talkies; Articles and Illustrations from Photoplay Magazine, 1928–1940, ed. R. Griffith (New York: Dover Publications, 1971), 275.

[27] Driscoll, Modernist Cultural Studies, 79-80.

[28] “The Quest for It”, Photoplay, April 1927, 109.

[29] In 1925, Photoplay stated that Clara has “given this nation of staccato standards its most vivid conception of this fantastic classification of girlhood and declares earnestly that she has folded her flapper ways and is under-taking the serious business of being a grown up young lady” (“Clara Bow”, Photoplay, June 1925, 78).

[30] Jon Lewis, Hollywood V. Hard Core, 92-96.