Motion picture serials, the forerunner of today’s serialized television dramas, have been around since the earliest days of the narrative cinema. Exhibitors rapidly realized that in order to assure continued audience attendance, open ended “cliff hangers” were sure to keep viewers returning week after week, to find out the latest plot twists, character developments, and of course, how the hero or heroine had escaped from the previous week’s peril. The first real serial, with multiple episodes and a running weekly continuity, was Charles Brabin’s What Happened to Mary? (1912), starring Mary Fuller as an innocent young woman who inherits a fortune, while the villain of the piece tries to separate her from her newfound wealth.

There was even a sequel to the serial, Who Will Mary Marry? (1913), as proof of the new format’s success. But the real breakthrough came in 1914, with Louis Gasnier’s The Perils of Pauline, starring Pearl White. Pauline established the hectic, action-packed formula that would persist until the production of the very last serial, Spencer Gordon Bennet’s Blazing the Overland Trail in 1956. Fistfights, non-stop action, minimal character exposition and a sense of constant, frenetic danger permeated The Perils of Pauline, and it generated a host of imitators.

|

Soon the “damsel in distress” format used in Perils of Pauline was being employed by a number of other serials, including Francis J. Grandon’s The Adventures of Kathlyn (1913), starring an equally athletic Kathlyn Williams, and Louis Feuillade’s epic mystery Fantômas (1913). Early serials were shown in weekly installments, a practice that continued throughout the lifetime of the genre, but early serial chapters could run as long as an hour, particularly in the case of Feuillade’s Les Vampires (1915), one of the most popular of the silent serials. These weekly screenings usually took place as a major part of the cinema program, and early serials were aimed at both adults and children. Occasionally, an enterprising entrepreneur would run a serial chapter throughout the week, to maximize attendance.

|

But by the late teens and early 20s, a fairly rigid structure had been defined through trial and error. Serials ran 12 to 15 episodes, with the first episode usually running a half hour, to set up the situation, and introduce the protagonists (and their adversaries) to viewers. Subsequent episodes clocked in at roughly 20 minutes. Each episode ended with what the industry termed a “take-out” – a scene of violent peril from which the hero or heroine could not possibly escape. The next chapter would pick up the action at the same point, but offer a “way out” for the lead character; a trap door offering a convenient escape, jumping from a moving car, or breaking free from some sort of fiendish device created by the serial’s chief villain.

The central characters in serials were more often types, rather than fully fleshed-out characters. In the early silent days, women were the protagonists of many of the action serials, thrown into situations of continual danger until the final reel unspooled. With the advent of women’s voting rights in 1920, the lead character became, more often than not, a heroic male; blindingly handsome, often endowed with above average mental acuity (as an investigator, adventurer, or soldier of fortune). A female companion was then introduced to support the hero’s efforts, with the possible addition of a young boy or girl “sidekick” to encourage adolescent identification with the serial’s characters. The hero was aided by a number of associates, who usually worked as a team to support the lead’s efforts. Lastly, and most importantly (for the leads in serials were usually rather bland), there was the chief villain, often masked, whose identity was not disclosed until the final moments of the last chapter.

Known in the trade as the “brains” heavy, the villain, in turn, would be aided by a variety of henchmen, or “action” heavies, who would unquestionably carry out the orders of their leader in a campaign of mayhem and violence that kept the serial’s narrative in constant motion. Indeed, though the serial format would serve as the template for weekly television series starting in the early 1950s, serials were far more violent than early television fare, noted for their extreme, non-stop action, their propulsive music scores, and seemingly impossible stunt work. And, unlike contemporary television series, which are open-ended – concluding only when audience interest has evaporated – serials were designed as a “closed set,” fifteen episodes and out, shot on breakneck schedules of 30 days or fewer, for completed films that could run as long as four hours in their final, chapter-by-chapter format.

Serials embraced nearly every genre – jungle serials [Jungle Menace [1937], with Frank Buck); crime serials (Alan James’ Dick Tracy [1937] with Ralph Byrd); the supernatural (Normal Deming and Sam Nelson’s Mandrake the Magician [1939], with Warren Hull); westerns (William Witney and John English’s The Lone Ranger Rides Again [1939], with Robert Livingston); and, of course, science fiction. Some of the earliest serials made were sci-fi efforts, including Robert Broadwell and Robert F. Hill’s The Great Radium Mystery (1919), Otto Rippert’s Homunculus (1916), and Harry A. Pollard’s The Invisible Ray (1920); all were successful with the public, who clamored for more.

Note that in almost all these cases, two directors were assigned to a serial, because of the sheer bulk of material involved. Sometimes directors worked on alternate days, to keep from becoming burnt out; in other instances, one director would handle all the action scenes, while another would shoot all the narrative exposition sequences. Serial scripts were immense, often running to 400 pages or more (or four times the length of an average feature), yet shooting schedules and budgets were often miniscule, and directors were expected to shoot as many as 70 “set ups” (a complete change of camera angle and lighting) a day to stay on schedule. Nat Levine, head of Mascot Studios, a prime purveyor of serial fare until his company merged with Republic Pictures, arguably the most accomplished of the sound era serial makers, used ruthless cost-cutting to bring in such films as The Phantom Empire (1935), a 12 chapter science-fiction/western hybrid serial directed by Otto Brower and B. Reeves “Breezy” Eason, starring a young Gene Autry.

Pushing his directors and crews to the limit, Levine also cut corners on actors’ salaries and other production costs, so that every dime he spent showed up on the screen. Actors, directors, and stunt men were left to fend for themselves; all that Levine cared about was finishing on time and on schedule. In between setups, Levine had an improvised dormitory set up on the Mascot lot in some vacant studio space, where exhausted stuntmen, actors and technicians could catch a few minutes sleep, and then grab a cup of coffee and some doughnuts to wake up, before being dragged back to the set. This arrangement also allowed Levine to keep an eye on his employees at all times, something like the production system used by the Shaw Brothers studios in Hong Kong in the 1970s. If you stayed on the lot all the time, Levine always knew where to find you.

As veteran serial director Harry Fraser recalled in his memoirs (Fraser would go on to co-script the first Batman serial in 1943, which was directed by Lambert Hillyer), Nat Levine was “the real Simon Legree without a whip” (102). Wrote Fraser:

I recall doing a Rin-Tin-Tin for him, released under the title The Wolf Dog [1933, co-directed with Colbert Clark], as I recall. I had an eighty scene [emphasis added] schedule one day, with the dog as the star and involved in most of the scenes. In addition to [former D.W. Griffith stock company member] Henry B. Walthall playing the human lead, there was a long list of supporting actors and actresses. Well, I came out with seventy scenes at the end of the day, but pushing everyone to the limit. But when the Serial King heard I was behind schedule by ten scenes, he practically accused me of causing the company to go bankrupt. My Scottish ire aroused, I listened to Nat rave on, then finally threw the script on the table and walked out of his office. (102)

![3.The Wolf Dog[3]](http://www.screeningthepast.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/3.The-Wolf-Dog3.jpg) |

Conditions at the other studios were little better. By now firmly consigned to the “kiddie trade,” where before they had also attracted adult audiences, serials were seen as being bottom-of-the-barrel product, and the major studios that churned them out (Columbia, Republic and Universal) saw them as strictly bottom line propositions. However, in many cases, viewers went to the theater each week not to see the feature attraction, but rather the serial, which kept them coming back for the next thrilling installment. Always cost conscious, serials would usually spend most of their production budget on the first three or four chapters, to entice exhibitors to book the serial, and capture audience attention; subsequent episodes were then ground out as cheaply as possible.

To top it off, the 7th or 8th chapter of many serials would be a “recap” chapter, in which expensive action sequences from earlier episodes were recycled for maximum cost benefit. Then, too, stock footage from earlier serials, as well as newsreel sequences, were often employed to keep costs down. Thus, most serials were compromised from the start. But occasionally, a serial hero would emerge who would rate slightly better treatment than usual, often a comic book hero transferred to the screen. Dick Tracy was one of the first of these; Flash Gordon was another, the star of three Universal serials produced between 1936 and 1940. Flash Gordon began its life as a comic strip with a lavish, full color Sunday episode on January 7, 1934, as created by Alex Raymond. The strip proved popular almost immediately and in 1936, Universal decided to gamble a significant amount of time and money bringing Flash to the screen.

While estimates range widely, the serial was roughly budgeted at $350,000, which was far more than the average serial at the time, usually brought in for $100,000 or less. Despite the generous budget, Flash Gordon was an ambitious project, requiring spectacular sets (many of them borrowed from other Universal productions), a plethora of special effects, and a fairly large cast of principal actors. Director Frederick Stephani, who also co-wrote the film’s script, was given a six-week schedule, but the circumstances surrounding the production were by no means luxurious. Even with an uncredited assist from co-director Ray Taylor, Stephani faced a daunting challenge. As Buster Crabbe, the star of the serial, and for many the archetypal, iconic Flash Gordon, remembered years later:

they started shooting Flash Gordon in October of 1935, and to bring it in on the six-week schedule, we had to average 85 set-ups a day. That means moving and rearranging the heavy equipment we had, the arc lights and everything, 85 times a day. We had to be in makeup every morning at seven, and on the set at eight ready to go. They’d always knock off for lunch, and then we always worked after dinner. They’d give us a break of a half-hour or 45 minutes and then we’d go back on the set and work until ten-thirty every night. It wasn’t fun, it was a lot of work! (as qtd. in Kinnard, 39)

|

In addition to Crabbe in the leading role, Jean Rogers was cast as Dale Arden, Flash’s nominal love interest; Charles Middleton, then in his 60s, made an indelible impression as Ming the Merciless, perhaps the most memorable of all serial villains for his pure cruelty and sadism; Frank Shannon portrayed Dr. Zarkov, Flash’s scientific advisor and mentor; and Priscilla Lawson appeared as Princess Anna, Ming’s daughter, who vacillates between loyalty to her father and a more than passing interest in Flash. Buster Crabbe, who as Clarence Linden Crabbe won a gold medal for swimming in the 1932 Olympics, was only 26 when he took on the role of Flash; while others, including future Ramar of the Jungle star Jon Hall tried out for the part, Crabbe was seemingly destined for the role.

![5.Charles Middleton as Ming, The Merciless;Buster Crabbe as Frash Gordon, Flash,[3]](http://www.screeningthepast.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/5.Charles-Middleton-as-Ming-The-MercilessBuster-Crabbe-as-Frash-Gordon-Flash3.jpg) |

As he told Karl Whitezel in 2000, Crabbe went to the audition for the role purely as a lark, with no real interest in the part. Watching Hall and others try out for the role from the sidelines, Crabbe was noticed by the serial’s producer, Henry MacRae. After a brief conversation, and with no audition at all, MacRae surprised Crabbe by offering him the part. Under contract to Paramount at the time, and not happy about it, Crabbe expressed polite disinterest: “I honestly thought Flash Gordon was too far-out, and that it would flop at the box office. God knows I’d been in enough turkeys during my four years as an actor; I didn’t need another one.” But MacRae persisted, and finally Crabbe told him that it was up to Paramount; “if they say you can borrow me, then I’d be willing to play the part” (Whitezel 52).

The two men shook hands on it, and a month later Crabbe found himself on a Universal sound stage, tackling the role that would become his lifetime calling card. His dark hair bleached blonde for the role, Crabbe dived into the hectic production schedule with a sense of cheerful fatalism; fate had given him the role, so he tried to make the best of it. As filming progressed, Crabbe grew more confident, and the cast and crew realized that they were working on something that was, to say the least, a notch above the usual serial fare. When production wrapped a few days before Christmas, 1936, there was no wrap party; that would have cost money. A few actors went across the street to a local bar for drinks, and director Stephani patted Crabbe on the back, thanking him for a “nice job,” and that was all.

At the time, Flash Gordon seemed like just another assignment for the young actor, who made six other features in 1936 alone as part of his Paramount contract. But, to Crabbe’s surprise, Flash Gordon made him a star overnight when it was released in March of that year. As the pseudonymous “Wear” in Variety enthused:

Universal’s serialization of the Flash Gordon cartoon character in screen form is an unusually ambitious effort. In some respects it smacks of old serial days when story and action, as well as authentic background, were depended upon to sustain their vigorous popularity. Here, instead, feature production standard has been maintained as to cast, direction, writing and background. [. . .] Buster Crabbe is well fitted for the title role, a robust, heroic youth who dares almost any danger. Character calls for plenty of action, which places him in a favorable light. Charles Middleton, best known of late for his western character portrayals, is a happy choice as the cruel Ming, [and] brings a wealth of histrionic ability to the part. Jean Rogers and Priscilla Lawson, besides being easy on the eyes, are entirely adequate, former as Dale Arden and Miss Lawson as Emperor Ming’s daughter. Frank Shannon indicates promise from his portrayal of the wild-eyed inventive genius [. . .] Flash Gordon should be a top grosser in serial field. (as qtd. in Willis, 49)

|

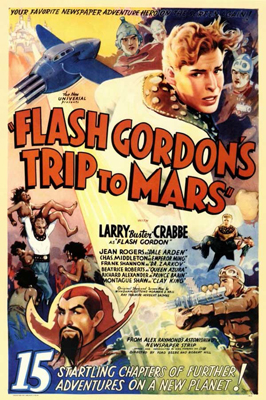

The die was cast, and as Flash, Crabbe achieved a certain sort of cinematic immortality, although to the end of his days he maintained a love/hate relationship with the role, convinced (perhaps correctly) that it had typecast him permanently as an action hero, when he longed for more serious parts. When the original film proved a box-office bonanza, Crabbe was called back for two sequels, the first of which was Ford Beebe and Robert Hill’s Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938), but for his second outing, the production was no longer a first class affair. As Crabbe remembered:

We started the routine of long days and short nights again, to grind out what would become a lesser product than the first had been, quality-wise. The producer took short-cuts, such as reusing some of the rocket ship footage filmed earlier, and replaying some of the landscape shots, assuming that audiences wouldn’t know the difference. [. . .] I never attempted to learn how well it did for Universal. Judging from the fact that, two years later, I would be called back for a third Flash Gordon serial [Ford Beebe and Ray Taylor’s Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe, 1940], I assume it was almost as successful as the first had been. (as qtd. in Whitezel 56)

![7.Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe Main Title[3]](http://www.screeningthepast.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/7.Flash-Gordon-Conquers-the-Universe-Main-Title3.jpg) |

In between these three iconic serials, in an attempt to break away from the Flash Gordon character, Crabbe also portrayed Buck Rogers in a 1939 Universal serial that was cranked out quickly on a modest budget, directed by Ford Beebe and Saul A. Goodkind. All the while, Crabbe kept appearing in “B” feature fare at Paramount, much to his chagrin, hoping for more substantial roles. But Paramount apparently saw little potential in the actor, and to Crabbe’s shock, despite his success with Flash Gordon, dropped him as a contract player in late 1939. Screen tests at other studios, including 20th Century Fox, yielded nothing. 20th Century Fox studio head Darryl F. Zanuck, after seeing Crabbe’s test, dismissed him with the words “he’s a character actor. We can hire all of them we need” (as qtd. in Whitezel 57).

Crabbe’s next film would seal his fate in Hollywood; he agreed to appear in a string of no-budget westerns for PRC, aka Producers’ Releasing Corporation, arguably the cheapest studio in Hollywood. Of all the studios, only PRC would agree to put Crabbe in a starring role, as astonishing as it seems today. His salary was roughly $1,000 a week for each six-day picture, with star billing, such as it was, thrown in as an added inducement. From there, it was all downhill. Crabbe had achieved lasting fame as Flash Gordon, but he would be forever identified with the role; now, the future seemed to promise only bottom-of-the-barrel action pictures.

But the die had been already been cast even with the cost-conscious production of Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe. Most of the cast was replaced by lesser-known actors for reasons of economy, with only Charles Middleton and Frank Shannon reprising their roles as Ming and Zarkov. As Crabbe remembered, with evident sadness:

I didn’t like the final Flash Gordon serial. We used a lot of scenes that we’d done before, the uniforms were the same, [and] the scenery was the same. Universal had a library full of old clips: Flash running from here to there, Ming going from one palace to another, exterior shots of flying rocket ships and milling crowds. It saved a lot of production time, but I thought it was a poor product that was nothing more than a doctored-up script from earlier days. (as qtd. in Whitezel, 59)

And yet, for all the compromises and production short cuts, the Flash Gordon trilogy stands as a major achievement in science fiction cinema history; indeed, the first Flash Gordon serial was selected in 1996 by the Library of Congress National Film Registry as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” No matter that it used recycled sets and costumes; nor that its score was comprised almost entirely of stock music from other Universal films, such as James Whale’s The Invisible Man (1935), Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Lambert Hillyer’s Dracula’s Daughter (1936), Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Black Cat (1934), or Rowland V. Lee’s Son of Frankenstein (1939), interspersed with snippets of new music by house composer Clifford Vaughan, and “lifts” from Liszt, Brahms, Tchaikovsky and Wagner (this last music cue from Parsifal, fitting in quite nicely). The trio of serials had made an indelible impact on popular culture.

The rocket ships were generally ineffective miniatures, the plots were predictably preposterous, and the special effects were often primitive, but somehow, none of this mattered. For the first two serials, at least, as Variety noted in their review, the cast performed with a sense of conviction and cohesion that lifted the project out of the ordinary and into the realm of myth and wonder. There is a genuine chemistry between Crabbe and Jean Rogers, and although the first serial, in particular, is clearly geared towards a juvenile audience, it nevertheless has an adult feel to it, perhaps because all the principals took their roles seriously, and didn’t condescend to the audience.

Charles Middleton, for example, had been a song and dance man earlier in his career, and had worked in films with everyone from Laurel and Hardy to director Cecil B. De Mille (in The Sign of the Cross, 1932), as well as providing a memorable foil for the Marx Brothers in Leo McCarey’s Duck Soup (1933), as well as appearing in a typically villainous role in John Ford’s adaptation of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1940). In all, Middleton appeared in more than 190 films, and worked in every imaginable role right up to his death in 1948. As with the other actors, Middleton played his role with conviction and sincerity, and as Ming, lent a certain gravitas to the entire enterprise. The world of Flash Gordon is at once fantastic, and yet real; one feels for the characters, who are drawn with greater depth than traditional serial protagonists, so that they seem to be actual personages, in an actual world, albeit one far removed from our own.

In the wake of the Flash Gordon trilogy, other science fiction serials would follow, mostly from Republic Studios. Many of the Republic efforts were quite effective, with high production values and superb special effects by Howard and Theodore Lydecker, including Spencer Gordon Bennett and Fred C. Brannon’s dystopic The Purple Monster Strikes (1945), dealing with an alien invasion from Mars; William Witney and Brannon’s memorably sinister The Crimson Ghost, in which the titular villain attempts to steal a counteratomic weapon known as a Cyclotrode, in order to achieve the (somewhat predictable) aim of world domination; Spencer Gordon Bennet, Wallace A. Grissell and stuntman extraordinaire Yakima Canutt’s Manhunt of Mystery Island (1945) with its plot device of a “transformation chair” to bring to life the serial’s villain, one Captain Mephisto (Roy Barcroft, Republic’s go-to heavy in residence), and a plot centering on the theft of a “radioatomic power transmitter”; and Harry Keller, Franklin Adreon and Fred C. Brannon’s Commando Cody: Sky Marshall of the Universe (1953), the only serial directly designed as a syndicated television series, thus providing a link between the non-stop frenzy of the serial format, and the more intimate domain of domestic TV fare.

![8. Commando Cody[2]](http://www.screeningthepast.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/8.-Commando-Cody2.jpg) |

Using recycled footage from Brannon’s King of the Rocket Men (1949), Radar Men From the Moon (1952), and Zombies of the Stratosphere (1952), Commando Cody’s format was a definite departure from the usual serial template; each 30-minute episode was self-contained, and yet the series maintained continuity, so that each episode could be run as a “stand alone,” or as a group. Released theatrically in 1953, the series of 12 episodes was picked up by NBC as a network series, running from July 16, 1955 to October 8, 1955 (Hayes 124). However, despite this attempt to move into television, Republic’s operation was winding down; the company’s last serial was Franklin Adreon’s non-descript King of the Carnival (1955). Republic officially closed its doors on July 31, 1959 as a production entity, although it still exists today as a holding company and a distributor of past product (Flynn and McCarthy, 324).

But though the later Republic, Columbia and Universal sci-fi serials provided predictably pulse-pounding entertainment, there seemed at length to be a perfunctory air about many of the serials in the mid-to-late 1940s. They were predictable, their plots unfolded like clockwork, they did the job, and got out. All nuances and much of the human element were gone. The serials had become a well-oiled machine, delivering predicable thrills on an assembly line basis, with characters that lacked depth, personality, or individuality. Serial leads were utterly replaceable, as were serial heroines; they did their job, and went home; dialogue was confined to exposition, with more and more repetition and recapitulation creeping in as the years passed by. The Flash Gordon serials created a world in which its characters lived, and took on definite human shape; subsequent serials, no matter how well crafted, lacked this three-dimensional quality.

Universal had been producing serials since 1914, with 137 productions in all to their credit, more chapter plays than any other company, until the ignominious end finally came with 1946’s Lost City of the Jungle, directed by Ray Taylor and Lewis D. Collins, which was shot almost simultaneously with The Mysterious Mr. M, directed by Collins and Vernon Keays. Lost City of the Jungle has achieved a certain notoriety as famed character actor Lionel Atwill’s last film; the actor was fighting what would ultimately prove to be fatal bronchial cancer and pneumonia, and was forced to leave the film in the midst of production.

Ironically, Atwill agreed to film his “death scene” for Lost City of the Jungle as his last work in front of the camera, leaving much of his role in the serial incomplete. Atwill then departed the Universal lot, never to return, and died on April 22, 1946. To finish Lost City of the Jungle, Universal used a double, created a new subplot to make Atwill’s character an underling instead of the “brains” heavy, and used outtakes for Atwill’s reaction shots. It didn’t work. Lost City of the Jungle was released the day after Atwill’s death, on April 23, 1946, to generally dismal results. When The Mysterious Mr. M, a nondescript science fiction serial was released to a similarly lukewarm reception, Universal called it quits.

Columbia fared little better. Lambert Hillyer’s incredibly racist Batman (1943), for example, the first appearance of the caped crusader on the screen, had a strong sci-fi element in the “mad lab” of Dr. Daka (J. Carrol Naish), a Japanese spy working to sabotage the allied war effort. While it was a solid enough effort, it relied on characters who were sketched in broad, charcoal strokes, with little shading or detail.

The Superman serials from producer Sam Katzman’s Columbia unit, 1948’s Superman, directed by Spencer Gordon Bennet and Thomas Carr, and 1950’s Atom Man vs. Superman, directed by Bennet alone, also have strong sci-fi elements, including disintegrator rays, teleportation machines, and, of course, the person of Superman himself, played in both serials by Kirk Alyn, as “a strange being from another planet who came to Earth with powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men,” as the narrative introduction for the subsequent Superman TV series would have it, in which George Reeves took over the title role. But in the two Columbia serials, whenever Superman was called upon to fly to the rescue, the legendarily cost-conscious Katzman switched to two-dimensional animation rather than using live action footage, which would have been more expensive, seriously compromising the production as a whole. The television incarnation of Superman ultimately served the franchise much more effectively, with vastly improved live action special effects.

Thomas Carr, for example, whose career as an actor stretched back to the silent era, and who actually played the role of Captain Rama of the Forest People in Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars, switched to directing program westerns in the 1940s, and would go on to direct a number of the early episodes of the Superman TV series, bringing much of the serial sensibility with him. But many viewers criticized the first season of the TV Superman series for its “excessive,” serial-like violence; it took a regime change at the producer level to create a more “user-friendly” Superman for home consumption. What had worked in the theaters, usually out of the view of parents and guardians on a Saturday morning, raised eyebrows when mom or dad watched along with their children in the family den.

Thus, a “softer” Commando Cody and Superman paved the way for 1950s Saturday morning children’s sci-fi; including a filmed West German half-hour version of Flash Gordon, Captain Video and His Video Rangers, Tom Corbett, Space Cadet, Captain Midnight, and Rocky Jones, Space Ranger, which arguably had the best production values of the lot (see Dixon). These Saturday morning teleseries would soon lead to more adult sci-fi, with The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits, Star Trek and Battlestar Galactica, all in prime time, and the children’s serial, as it had flourished in the past, would fade into the mists of our collective memory.

Yet of all these serials, it is the Flash Gordon trilogy that still commands our attention today. Its scrolling titles and futuristic gadgetry clearly inspired George Lucas’s Star Wars series, particularly the initial episode, released in 1977. It has inspired a host of remakes; after the 1954-1955 West German series, there was an animated series entitled The New Adventures of Flash Gordon in 1979-1980, Mike Hodges’ 1980 feature film featuring Max von Sydow as Ming the Merciless, which failed to live up to expectations, as well as Michael Benveniste and Howard Ziehm’s X-rated parody Flesh Gordon (1974), and a sequel, Ziehm’s Flesh Gordon Meets the Cosmic Cheerleaders (1989). As of this writing, director Breck Eisner has announced that plans are in the works for a new 3-D version of Flash Gordon, which will bypass the 1980 film and the Universal serials, and go straight back to Alex Raymond’s comic strip for inspiration. So it seems that Flash will always be with us, and that the original serials, tacky and art deco in design though they may be, will remain talismans of our cinematic past.

As for the sci-fi serial format itself, the serial truly paved the way for the television series of the 1950s and beyond; it offered compact thrills and a continuing storyline within the confines of a twenty-to-thirty minute template, and, just like contemporary television serials, kept audiences coming back for more week after week. Today’s teleseries are considerably more sophisticated, both in their technology and in their narrative structure, and the characters that inhabit them are, for the most part, fully dimensional human beings, not cardboard archetypes. And yet they owe a considerable debt to the serials, which inhabited a world of constant action, peril, and imagination, but were ultimately too simplistic for contemporary audiences. The half-hour television series format simply erased the serial from public consciousness; the theatrical serial had become obsolete.

People didn’t have to go out anymore to see the latest adventures of their favorite sci-fi heroes and heroines; they could watch them on TV. And so, just as Flash Gordon and its sci-fi serial brethren predicted much of our future technology (rockets, telescreens, the possibility of interplanetary travel), it also paved the way for the medium of television, with its chaptered format, rigorous schematic structure, and cliff-hanging plot lines. The future of sci-fi television, as well as theatrical series (the Star Wars and Star Trek feature films are two obvious examples) would play out in the 60s, 70s, 80s and continues up to the present day; many of the plots are as fantastic as the early science fiction serials, even if the special effects have markedly improved. But the Flash Gordon serials played an important part in the creation of contemporary televisual formats, as well the serial-like sequel formats of many contemporary theatrical science fiction franchises, and offered to audiences a sense of wonder and amazement that still resonates today, and continues to gesture towards the future.

Works Cited and Consulted

Ackerman, Forrest J. “The Ace of Space.” Spacemen 4 (July 1962): 34-41.

Barbour, Alan G. Cliffhanger: A Pictorial History of the Motion Picture Serial. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel, 1984.

. Days of Thrills and Adventure. New York: Macmillan, 1970.

Barshay, Robert. “Ethnic Stereotypes in ‘Flash Gordon.’” Journal of the Popular Film, Winter 1974: 15-30.

Behlmer, Rudy. “The Saga of Flash Gordon.” Screen Facts, 2, 4, 1965: 53-62.

Dixon, Wheeler Winston. “Tomorrowland TV: The Space Opera and Early Science Fiction Television,” The Essential Science Fiction Television Reader. J. P. Telotte, ed. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2008: 93-110.

Ellis, John. Visible Fictions: Cinema, Television, Video. London: Routledge, 1982.

“Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars.” Look Magazine, 15 Mar. 1938: n. pag.; 29 Mar. 1938: n. pag.; 12 Apr. 1938: n. pag.

Fraser, Harry L. I Went That-A-Way: The Memoirs of a Western Film Director. Wheeler Winston Dixon and Audrey Brown Fraser, eds. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1990.

Grossman, Gary H. Saturday Morning TV. New York: Delacorte, 1981.

Hayes, R. M. The Republic Chapterplays: A Complete Filmography of the Serials Released by Republic Pictures Corporation, 1934-1955. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2000.

Henderson, Jan Alan and Burr Middleton. “Behind the Ming Dynasty: Revelations from the Emperor’s Grandson, Burr Middleton,” Filmfax 85 (2001): 50-58, 87.

Kinnard, Roy. Science Fiction Serials. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1998.

Kinnard, Roy, Tony Crnkovich and R. J. Vitone. The Flash Gordon Serials: A Heavily Illustrated Guide. Jefferson, NJ: McFarland, 2008.

Lahue, Kalton C. Bound and Gagged: The Story of the Silent Serials. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1968.

Mitchell, Robert. “Flash Gordon.” Magill’s Survey of Cinema: English Language Films. Second Series, Vol. II. Ed. Frank N. Magill. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Salem Press, 1981: 796-799.

Parish, James Robert, and Michael R. Pitts. “Flash Gordon.” The Great Science Fiction Pictures. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1976: 125-127.

Rainey, Buck. Serials and Series: A World Filmography 1912-1956. Jefferson, NJ: McFarland, 1999.

Rovin, Jeff. “Flash Gordon.” From Jules Verne to Star Trek. New York & London: Drake Publishers, 1977: 44-45.

Schutz, Wayne. The Motion Picture Serial: An Annotated Bibliography. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1992.

Steinbrunner, Chris, and Burt Goldblatt. “Flash Gordon.” Cinema of the Fantastic. New York: Galahad Books, 1972: 125-150.

Turner, George. “Making the Flash Gordon Serials.” American Cinematographer, June 1983: 56-62.

Vermilye, Jerry. Buster Crabbe: A Biofilmography. Jefferson, NC: 2008.

Whitezel, Karl. “Buster Crabbe: An All-American in Outer Space,” Filmfax 79 (2000): 59-59.

Willis, Donald, ed. Variety’s Complete Science Fiction Reviews. New York: Garland, 1985.

Witney, William. In A Door, Into A Fight, Out A Door, Into A Chase: Moviemaking Remembered by the Guy at the Door. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1996.