Uploaded 1 March 2001

Table of contents

1. The exigency of writing

2. On writing and directing

3. Lois Weber, writer of cinema

4. Lois Weber, writing exigence

5. Lois Weber and the mirror of cinema

6. Appendix: Lois Weber’s surviving films

1. The exigency of writing

The infinite conversation [2]

Wait, what is the “exigency of writing” of which Blanchot writes? Whence the urgency, the emergency, and where directed? Another play with possession? Blanchot is famous for his”of” (the “of” of Blanchot is The writing of the disaster and The madness of the day and The space of literature and The gaze of Orpheus). Is it the urgency felt by the writer: the need to write and? Yes. Or is it the urgency imbued by writing: the need to read and? Yes. Or the urgent need within writing: the battle of writing and language, our epoch’s need and? Yes I said yes, perhaps most of all, Yes.

no longer the writing that has always (through a necessity in no way avoidable) been in the service of the speech or thought that is called idealist (that is to day, moralizing), but rather the writing that through its own slowly liberated force (the aleatory force of absence) seems to devote itself solely to itself as something that remains without identity, and little by little brings forth possibilities that are entirely other: an anonymous, distracted, deferred, and dispersed way of being in relation, by which everything is brought into question – and first of all the idea of God, of the Self, of the Subject, then of Truth and the One, then finally the idea of the Book and the Work – so that this writing (understood in its enigmatic rigor), far from having the Book as its goal rather signals its end: a writing that could be said to be outside discourse, outside language.

Outside language. Writing urgently pours forth. In an. (Unending stream.) How does such exigent writing happen? How, and under what circumstances, does “moralising” writing metamorphose into something “without identity”that “brings forth possibilities that are entirely other”? And, how far is that process under conscious control? How far is it the product of a writer’s will and how far the inevitable result of writing and writing again, or of writing in the age of its technological reproducibility?

Yet another word of elucidation or obfuscation. When I speak of “the end of the book,” or better “the absence of the book,” I do not mean to allude to developments in the audio-visual means of communication with which so many experts are concerned. If one ceased publishing books in favor of communication by voice, image, or machine, this would in no way change the reality of what is called the”book”; on the contrary, language, like speech, would thereby affirm all the more its predominance and its certitude of a possible truth. In other words, the Book always indicates an order that submits to unity, a system of notions in which are affirmed the primacy of speech over writing, of thought over language, and the promise of a communication that would one day be immediate and transparent.

(In parentheses Orpheus might glance forwards and backwards at the same time). Which is to say, for my purposes that in common usage the Film is the Book and directing = writing. How does directing, then, create the circumstances in which “the Film” no longer holds the ultimate value? I would say, at least partly insofar as directing makes “incomplete” films, films which are inadequate – bad films, then, at least by most lights. One of the least remarked effects of the auteur gaze in criticism was to downplay the Film in favour of a grander, less defensible (oh yes, much less defensible), ultimately ungraspable text, the textual auteur. That is, to some, perhaps to a significant, extent, auteur criticism took the steps here suggested by Blanchot, reading writing “without identity”.

(I am not Orpheus). And, subsequently, the ideologically-driven defeat of (bourgeois) auteurism, resurrected the Film. My own analyses nowadays almost always place “the film” where the name of the director used to be placed. It seems more accurate to place the weight of authority on the present text rather than on an absent, past, generator. The author is the identity we can do without. But at the same time, when I do that, I am perforce ignoring precisely that writing in the film which tends to undermine the Film – or, rather, I am misapprehending it, vitiating it (since I do not ignore it, but rather, seek it out). This argument for authorship is also an argument for Tom Gunning’s book, The Films of Fritz Lang.[3] Tom Gunning doesn’t want to be an auteurist. He is more sophisticated than that. But what he does is to destroy the Films by writing about each of them, simultaneously writing them into a single, unfinished, ungraspable text, a text without identity, articulated in many permutations: Platonism, postmodernism. A text he calls Lang.

Now it may be that writing requires the abandonment of all these principles, that is to say, the end and also the coming to completion of everything that guarantees our culture – not so that we might in idyllic fashion turn back, but rather so we might go beyond, that is, to the limit, in order to attempt to break the circle, the circle of circles: the totality of the concepts that founds history, that develops in history, and whose development history is. Writing, in this sense – in this direction in which it is not possible to maintain oneself alone, or even in the name of all without the tentative advances, the lapses, the turns and detours whose trace the texts here brought together bear (and their interest, I believe, lies in this) – supposes a radical change of epoch: interruption, death itself – or, to speak hyperbolically, “the end of history.”Writing in this way passes through the advent of communism, recognized as the ultimate affirmation – communism being still always beyond communism. Writing thus becomes a terrible responsibility. Invisibly, writing is called upon to undo the discourse in which, however unhappy we believe ourselves to be, we who have it at our disposal remain comfortably installed. From this point of view writing is the greatest violence, for it transgresses the law, every law, and also its own.

Communism. You are not surprised. Blanchot’s is a passage of references which is also a passage of acceptance. Here writing again finds its “moralising” voice – in its “terrible responsibility . . . to undo” the discourse in which we find ourselves, to break “the law, every law and also its own”, a missionary of transgression through the violence of language.

2. On writing and directing

For writing about the cinema, Alexandre Astruc’s”caméra stylo” essay signalled a detour into language, which was to make directing a form of”enunciation”.[4] But what impelled Astruc, initially at least, was the parallel between writing and directing, not between film and language. In his evolutionary understanding, film language was being brought into being through cinematic writing, created by praxis. When others (let us say, Christian Metz), stopped (for many years) to explore the possibility of film language, language and cinema, the impersonal enunciation or the site of the film, Astruc assumed that if these things did not exist he and his film making friends would soon bring them about. He was describing and advocating an activity, a verb, not a state or material of that activity, not a noun.

But at the same time, Astruc could only conceive of writing as a deliberate engagement with language. He criticised Henri Georges Clouzot for using film imagery tinged with “heavy associations” (19), and he said that the real problems for film makers were “the translation into cinematic terms of verbal tenses and logical relationships” (22). In so doing, he bought into a model of “good writing” which one can still see at work today in most analyses of film texts.

Directing is most usually thought of as an activity intimately involved with the conventions of film usage (“film language”). This seems commonsensical enough. What I will call “good directing” understands itself as the proper use of film in film making – in other words, as a good film activity rather than a good activity in which film happens to be used. “Good directing” easily becomes directing that is conscious of the problematic relation between language and discourse, conscious that this relation must be always re-negotiated at every point in the text.

In “good directing” the text is seemingly saturated with sense to the extent that it is saturated with language: every image and every cut portends. Moreover, everyone understands that there is a relation of complex and profound significance between semiotic and structural levels in this kind of directing (that is in directing as an art and directing as possession) – between shots and sequences, sequences and episodes, episodes and the whole.

This is a model, as I have suggested, that owes its origin to a model of “good writing”, a privileged relation between writing and language, that almost everyone accepts. But there is also writing that does not conform to that model and that may, nonetheless, be good. There is writing”without identity” that takes language for granted or that finds language a barrier that cannot be surmounted, that is, writing that is entirely inside or outside language – in which language is wholly familiar or utterly strange. This is recognisably writing, but it is not what one thinks of when one thinks of writing. Edgar Rice Burroughs and Agatha Christie practised this kind of writing. They wrote entirely within language, comfortably, familiarly, taking language for granted, only making themselves felt on the title page. So did Mickey Spillane and the poet Julia Moore in another, unschooled or naive, way. They wrote outside language: they were uncomfortable with the limits of language, they had more to say than language alone could say, they wanted language to be themselves.

In such writing, the well-turned phrase is only an artifice within the diegesis (usually a clever line of dialogue, a “telling” camera movement), not an organic part of the whole. Astruc would be disdainful (he was good at that). Virtually all of the thinking and the art in this kind of writing or directing happens somewhere beneath or above language and is often apparent as aspects of structure or of figuration abstracted from the verbal or the cinematic – even sometimes in the form of “heavy associations” at those levels.

Nor is it the case that this kind of writing”stops” at a structural or figural level – that it resists more detailed analysis.

A banal sentence truly chosen at random from Burroughs:

Tarzan at the earth’s core [5]

This sentence is quite clearly an example of the delineation of character through Roman Jakobson’s”poetic function”. Poetry, or the foregrounding of language, is apparent not only in the alliteration of the s (“suggestion … smile … smouldered … his … eyes”) – which surely dictates”suggestion”, in many ways the key word of the sentence – but also in the way vowel sounds are deployed from loose (“As Tarzan ate”) to tight (“in his eyes”). One might also note that one, clichéd, word, “smouldered”, acquires additional levels of sense in context as one realises that in the scene, the food being eaten is not cooked and that Tarzan is remembering a civilised aristocrat’s reaction to underdone fowl.

What provokes critical resentment in such analysis is usually the question of conscious effort: did Burroughs work on this sentence? Did he make the”good writing” analysis can discover in his work? This is for some the real question of “authorship”(the critic, not the writer, is the true author) – but in the end it is, I think, more a question of the kind of writing involved, anonymous writing that takes language for granted, that makes no demand on language, merely makes a use of it. A writing whose formal causes and results are not really understood. And, for that reason, this is also perhaps a question of writing in general, a question that assumes that writing can happen sometimes because in spite of language, as it does in Julia Moore’s famous dictum, “literary is a work very difficult to do”. This wonderful sentence is not “good writing”, but an example of the very best, most precious, writing done because in spite of language, outside language.[6]

In film one of the best known directors working entirely within language is Howard Hawks. The difference between Hawks’s films and, say, Josef von Sternberg’s is simply that Hawks’s effects are never laboured and, consequently, he is never caught pointing to the cinema/himself as von Sternberg, a master of cinematic language, always is. Some might say that working within language is the common place of many “classical Hollywood”directors, like Raoul Walsh, John Ford, George Cukor and Dorothy Arzner. Some might even say that such an approach was almost a necessity for survival in Hollywood from the mid-twenties into the fifties at least.

Among the notable women directors, Alice Guy, it seems to me, always worked entirely within language. This is not surprising, since she contributed quite a lot to the formation of that language and was surely comfortable with what she had done.

But certain film makers inside and outside Hollywood have tended to use the cinema naively, displaying a certain “archaic” sensibility even in films made with great professional or aesthetic aplomb. Such directors seem to have understood cinema as a barrier to be transcended rather than as a medium of expression. Despite their apparent primitiveness, they made use of film “not so that we might in idyllic fashion turn back, but rather so we might go beyond, that is, to the limit, in order to attempt to break the circle, the circle of circles”. I am thinking of Abel Gance, King Vidor, Cecil B. DeMille, Ed Wood. And, I would say, Lois Weber.

3 Lois Weber, writer of cinema

She was a writer rather than a playwright or screenwriter, and as if to emphasize this fact, her 1915 feature, Sunshine Molly, begins with a shot of hands opening a book titled Sunshine Molly by Lois Weber; all nondialogue titles consist of pages from that book; and the reels close with the title “End of Book 1,” and so forth.[7]

Of course it is much easier to make a case for a film maker as a true cinematic writer in Astruc’s sense than it is to argue for her naivete. Lois Weber has all the proper and professional qualifications for authorship – more, in fact, than many film makers who followed her. She did indeed write most of the films she directed. The years of her greatest productivity, 1912-1921, were also years in which she routinely enjoyed the most complete control possible over the films she made.

By 1912 she and her husband, Phillips Smalley, were “prima facie heads of Rex” (a production company they took over from Edwin S. Porter)[8] , and in 1917 they formed “Lois Weber Productions” which continued to produce her films until 1921. (The Blot was the last “Lois Weber Production”). According to Weber’s biographer, Anthony Slide, Weber and/or Weber and Smalley usually operated as an independent production entity on the pictures they made even when no umbrella company was credited through all the years of their association with Universal and the Bosworth Company.

“I would trust Miss Weber with any sum of money that she needed to make any picture that she wanted to make. I would be sure that she would bring it back.”(Carl Laemmle)[9]

Lois Weber Productions were a good investment, cost-effective. The company made movies cheaply: in later years at least shooting on location even for interiors, using a small cast, working fast. Its somewhat sensational topics and titles guaranteed at least a modest box office return, and at times may have done much better than that. At Universal under Carl Laemmle Weber seems to have been mostly allowed to make the films she wanted in the way that she wanted, but there is some evidence that her independence was pretty severely constrained after the apparent box office failure of the four films that Lois Weber Productions made at Paramount between 1919 and 1921 (including The Blot, which, although made for Paramount, was released independently). She rejoined Universal in 1922 and made three more films for that company, but left in 1925 after a picture she felt should have been hers by right was assigned to someone else. She only directed four films in the eight years from 1926 to 1933, which Slide reports as the nadir of her career.

Not only does she direct a picture. Before she begins to direct, she writes her own rough scenario from the story selected. It may be her own story (she has had several successes with”originals”), or it may be a book, or a play. In any case, she comes to a more satisfactory understanding of what she wishes to make of it if she does not only the first roughcast, but the full continuity, herself. By this time she sees the picture complete, though occasionally she changes her mind and makes a few alterations. Then she writes captions, for this seems in her eyes to be part of a director’s “job.” When there is a chance for fun Lois Weber – who looks so soft and sweet – can be as funny, as “smart,” as any of the expensive “gag men” whom all the studios keep on high salaries nowadays, to “pep up” a languid film. Though she never uses slang in conversation, and rather dislikes it personally, as she dislikes smoking, no one can use slang to better advantage on the screen than she. No one can depict the”hard boiled” modern flapper with keener touches than can this seemingly old-fashioned, gentle-mannered, soft-eyed woman, Lois Weber.[10]

In testimony like this, it is possible to discern the figure of Astruc’s compleat auteur, a Hitchcock before Hitchcock: screenwriter, dialogist, wit, hip to the jive, viewing this modern age with eyes ascetic and wise. But there is another move here too. Inextricably tangled in the description of the cinematic writer is the cinematic woman: she who transforms a questionable masculine domain to something fit for a lady.

Her writing and her womanliness are one. She writes woman on her films; she makes le caméra stylo into l’ouverture toute voyante, an omphalos knotting all lines of sight into her own. She can act as a man, be a man, without ceasing to be always a woman. Unselfconsciously, like so many women before and after her, she unsexes language:

The real director should be absolute. He alone knows the effects he wants to produce, and he alone should have authority in the arrangement, cutting, titling or anything else which it may be found necessary to do the finished product. What other artist has his creative work interfered with by someone else?[11]

4. Lois Weber, writing exigence

“The most extraordinary thing about my sister is that she is so ordinary.”(Ethel Weber)[12]

People should listen to siblings – even siblings who speak in clichés. We assume that extraordinary films are made by extraordinary people. But if something out of the ordinary is required even to survive in the picture biz (and they are always telling us that it does), then surely the most unusual movies, the ones that look different from any of the others, will be the ones exscribing an ordinary vision, crafted by those ordinary people who by luck (or a spouse’s ambition) are vouchsafed cinematic opportunity. I am not just being clever here, or at least not in the matter of ordinary vision. The greatness of Henri Rousseau=s painting is as dependent upon the banality of what it discloses, its percepts, as upon the uniqueness of the manner of its disclosure, its affects: it is an extraordinarily ordinary vision. The same may be said for other artworks called naive.

If women would only understand that many men are not half so interested in a well-ordered house as they are in a well-groomed wife, things might be different.[13]

Now there is an ordinary sentiment. It is a quotation from Lois Weber encapsulating the message of one of her films for Paramount: Too Wise Wives (1921). This is also the message of many of Cecil B. DeMille’s “naughty” comedies of marital infidelity made for Paramount around the same time. Weber is not DeMille, although they shared a common sense of the mission of the cinema. Weber’s film is a transformation of De Mille’s sex comedy into a comedy of domesticity and the everyday. When women change clothes onscreen in Too Wise Wives it is because they are shopping and the film wants to depict a desire for nice things, not because they are provocative minxes and film wants to inflame a desire for sexy bodies. And in the end, the result is that the sincerity of Weber’s attempt to persuade is as clearly apparent as De Mille’s conflict-ridden prurience.[14]

In moving pictures I have found my life’s work. I find at once an outlet for my emotions and my ideals. I can preach to my heart’s content, and with the opportunity to write the play, act the leading role, and direct the entire production, if my message fails to reach someone, I can blame only myself.[15]

I’ll tell you just what I’d like to be, and that is, the editorial page of the Universal Company. . . The newspaper and the clergyman each do much good in their respective fields and I feel that, like them, I can, in this motion picture field, also deliver a message to the world . . .[16]

Weber (and DeMille) wanted to use the cinema to preach, to editorialise, to educate. Just as it was for Lenin and Lunacharsky, for them the cinema was the most important of all the arts. Forget DeMille, Weber had the credentials. She was the daughter of a minister who had spent several years in missionary street work. Throughout her career, she spoke about the uplifting potential of the motion picture and made movies that were clearly intended to be good for their audiences. Thus it seems clear to many of those who have written about the director that her film making was the equivalent of “the writing that has always (through a necessity in no way avoidable) been in the service of the speech or thought that is called idealist (that is to day, moralizing)”. If her films appear naive, one would assume from this understanding, it is at least in part because that kind of moralising is old-fashioned, that kind of idealism is old-fashioned.

But this is an idealist, even naive, understanding that depends on taking the quotations attributed to her at face value: accepting their authenticity and their intention, not reading the events or the words very carefully at all.

Why would we believe even that Lois Weber said the things that trade papers and fan magazines printed when we know that trade papers and fan magazines usually printed what publicists gave them to print? Why would we believe that Lois Weber, for example, said that her film Too Wise Wives advocated making one’s self beautiful for one’s husband, when the film does nothing of the kind? In point of fact the woman in the film who makes herself beautiful for her husband is “too wise”: she is deceiving him by pretending a subservience to his desire that she does not feel. In this film, the two wives who are too wise learn to treat marriage rationally, as a partnership based on mutual respect and trust. They learn not to be too subservient and not to be too manipulative. This is a complicated lesson and it does not make for sensational cinema – or, as we have seen, for a sensational interview.

And the minister’s daughter? Slide wants to discover in Weber some trace of Mary Baker Eddy, but it is possible that there may be some Aimée Semple MacPherson too. Indeed, in his account of her early life, Slide does not describe a minister’s daughter who happened to end up in show business, but a person with a strong desire to be noticed who turned ceaselessly to performance and self-display, no matter what the circumstances of her life happened to be. Jayne Mansfield no less.

She did not spend her teenage years preparing for the pursuit of God nor for the pursuit of a husband. Instead, she was a concert pianist at sixteen (1895?), quitting within a year. She did not retire to a convent, nor did she return home to pursue a husband. Instead, she joined a group of religious performers, the Church Army Workers, for two years. Apparently they played mainly for prostitutes (her street missionary work). Yet when the minister, her father died, she did not take up his preaching, nor did she take up the so-often-postponed pursuit of a husband. Instead, she took up the advice of an uncle and a career on the musical stage, joining Phillips Smalley’s touring company when she was 25 and marrying him a year later (1905), when he was 40. Smalley may have been an intelligent man; he certainly was a snob with good family connections, a womaniser, and (at least later) an alcoholic.

Had she pursued this husband? Marriage apparently meant that she could no longer perform on stage. Nothing daunted, while the theatre company was touring, she began to work in films. She was soon a writer-director-actor of talking pictures for Gaumont (1908), then under the management of Herbert Blaché, husband of the first important woman film maker, Alice Guy, who may have been in temporary retirement at the time and at any case does not seem to have been much in evidence in Weber=s life. Smalley, seeing an opportunity (and perhaps also protecting his interests in other ways), joined his wife in films and the two worked mostly in partnership after that until 1919, when their marriage seems to have begun a final downward spiral (they were officially divorced in June, 1922).[17]

Just as I started to play a black key came off in my hand. I kept forgetting that the key was not there, and reaching for it. The incident broke my nerve. I could not finish and I never appeared on the concert stage again. It is my belief that when that key came off in my hand, a certain phase of my development came to an end.[18]

This account of why Lois Weber quit being a concert pianist is an interesting one. I do not think that she took her commonplace accident as a religious or mystical call, but she surely seems to attribute to it, to the event, a significance beyond the common.

There is an obvious psychological level here: a commentary about the forging of character, about someone who needs to be in control, about growing up. But there is also a level of reading and writing, of the cinema, in the story. We can see what happened in close-up: the key breaking, the hand reaching (it is a right hand, we sense this with certainty because we can see the hand trying over and over to strike the missing key as the tempo increases, until, in futility and in long shot, the girl slams both hands down upon the keyboard and dissolves in weeping, running frantically from the stage while the concert master wrings his hands and wonders if he will have to refund everyone’s money). This anecdote is the climactic incident in the imaginary film of Lois Weber’s life; and what happens in this incident is that something very ordinary and quite contingent is transformed into something filled with fate and import (a woman detects perfume in a letter, or sees her mother in the act of stealing food): meaning is exscribed, writes itself out of the mundane so that it can be read anew, exchanging the thing for a symbol.

Aside from Hypocrites, allegory does not play a strong role in Weber’s films.[19]

On the contrary. All of Lois Weber’s work is allegorical, like the story of the black key. Rather than the most realistic, hers is the most unreal, most literary, most symbolic cinema. Nothing in it is as it appears. Everything means. Nothing is specific and itself: no pair of shoes, no Ford motorcar, no lovely Claire Windsor, no dashing Louis Calhern, no carefully chosen authentic location setting (The Blot). They all stand for something else. No indices, only icons. The mountain of detail that she assembled was never intended to serve as a mere record of life as it is lived. Rather, it was intended to present earthly stories with heavenly meanings, to mirror truth, which is to say, to disclose the Being beneath existence, God in the details, purpose of life.

She used film as a central theme in her 1916 production, Idle Wives, in which a husband and wife (played by Weber and Phllips Smalley) drift apart. They, and others in the story, are brought back together after viewing a motion picture titled Life’s Mirror, which, quite naturally, is advertised on the theater marquee as a film by Lois Weber.[20]

Allegory insists on the unfulfilled nature of the text by gesturing towards its (ultimately unsatisfactory) completion, which is also its origin, elsewhere. It is a state of constant reference, always becoming, shifting, troping. We have seen, in Slide=s own testimony, how two of Lois Weber=s films make this gesture turn upon itself and into fiction (in Sunshine Molly, an imaginary book by Lois Weber and in Life’s Mirror, an imaginary film by Lois Weber). In other films, the gesture is more palpable and the referents more “real”. In The Blot there is a famous instance, which most sophisticated commentators take as the “message” of the film, where an actual issue of The Literary Digest is cited and passages in it reproduced.[21] The Hand that Rocks the Cradle, a film based on events in the life of Margaret Sanger, quotes directly from a speech given by Judge John Stelk on February 8, 1917.[22] In Hypocrites (1915) there are quotations attributed to Browning and Milton, a reproduction of a painting by Faugeron and an article about that painting by Elbert Hubberd that apparently appeared on July 12, 1914. In 1915 at least, Weber claimed several times in those interviews of dubious authenticity that she found inspiration even for the films that did not explicitly display them in newspaper editorials and commentaries.[23] The result is not only a cinema of preaching or editorialising, but also, and consequently, a cinema of allegory which manifestly highlights its own insufficiency as communication, claiming only that it encrypts another, impalpable text.

Doubtless we need to search carefully for what has been concealed for us to find in these films.

What is the blot of The Blot? One particular intertitle seems to settle the matter very directly.

it is a blot on the present day civilization that we expect to engage the finest mental equipment for a less wage than we pay the commonest labor

Slide says that “The title [of the film] refers to the blot on civilization, that is, that we expect to hire the finest mental equipment for less than we pay the common laborer”(118), and Jennifer Parchesky, who has written the best and most thorough discussion of the film, also accepts the fundamental significance of this titular intertitle, claiming that “Phil West’s pronouncement . . . provides a key to what goes without saying but is everywhere visible in the film: the anxiety about the deterioration of the collar line that had formerly distinguished white-collar workers from blue-collar laborers.” [24]

Of course, both Slide and Parchesky are right – mostly right, partly right. Weber, who usually wrote her own intertitles, of course intended this one to remind viewers of the title of the film and to indicate what it was really about. And that was, of course, because otherwise viewers might have missed the point. (As Parchesky’s comments suggest, even with this prompting, viewers may still miss the real point – of course).

But we may agree to understand something more in these words, so easy to copy incorrectly, which are, strictly speaking, neither those of an intertitle nor something Phil West pronounces. They occur, in fact, in an insert shot of letter from West’s father to his son and they are a quotation from a letter written previously by West to his father. That is, they are, most emphatically, written words (twice, or even three times written – if you count the once for us). The letter contains more words than these – so many more, in fact, that its contents must be extended over two insert shots. In the first such shot, which contains the quotation, West’s father writes of the pleasure and astonishment of his son’s letter and a certain guilt in having left his parental duty to West=s university teachers. In the second shot, which classically completes and extends the narrative of the first, the letter of the father declares his intention of seeing his son and discussing the matter further “if you feel so strongly about it”, provided he is “not so completely changed as to make recognition difficult”.

It is during that meeting that The Literary Digest is produced and its printed contents inserted on screen and into the film in two shots that recall the two devoted to the typewritten letter. West shows these words to his father, again using writing to make concrete his personal sensibility as he had in originally writing the letter we cannot read. All this writing addresses his father for him before West himself speaks (in written intertitles). And all that he has witnessed and discovered during the long time that the story has played itself out (the effects of low wages on the family of a university teacher; his understanding of the prevalence of this condition) is crystallised in writing, in a single word, his trope: “the blot”. Everything else serves only to gloss his word, to fill it out, explain it. The film is completed, swallowed, for a moment, in that word, just as the film flowed initially from it, from the title that prefaces the action.

The meeting between West and his father is displayed in an interesting manner. It takes place over two locations, neither of which play any part in the rest of the film: a study or den and what may be a university campus. During the time with his father, West does not mention the family he has come to know or the woman who has won his heart. Instead he speaks in banal generalities of what is owed good teachers. Slide says that the scene is “an awkward moment … preachment rather than entertainment” (118), but this may only be another way of recognising that it exists in an uneasy relation with the narrative, tracing actions of a different order within its different space. Here, where we are at the point of the film, so to speak, we are hardly in the diegesis at all: we have been cinematically written outside the everyday story and rapt into the realm of big ideas, that place where the ordinary is transmuted into the extraordinary in the touch of writing.

Indeed, this is an awkward moment, one of the few moments when The Blot‘s naivete is frankly, even fulsomely displayed. The clumsy blot of this sequence exscribes itself as something which happens when one writes on heedless of propriety, a sudden flood obscuring lines of careful planning, la reste d’une ouverture saignante. Good directing is enemy here, proper structure, organic wholeness – the Film itself, yes. This is ciné-writing outside cinema because the cinema cannot be trusted to declare what must be said. Control must be wrested from the looped certainty of seducing story, admonitory words deployed anew to point at the point, heavy words that form the impossible sounds of inner speech. The mark of the blot I cannot show.

5. Lois Weber and the mirror of the cinema

Lois Weber’s imaginary movie was called Life’s Mirror. It did not work the way an ordinary mirror does, however. Instead of reflecting the characters in Idle Wives, it reconciled them: what they saw in the movie was not what they were but what they could be. The title of this imaginary film and the way it works suggests quite strongly that Weber’s idea of the cinema was derived from the commonplace Aristotelianism of her day. We may suppose that she believed that true art holds a mirror up to nature – it is an imitation of life – but the artful image in the mirror is refined and heightened: it shows the essential – crafting a moral or a conclusion. The cinema is peculiarly susceptible to this kind of interpretation because of its apparently close relation to reality (it “reflects” what is before the camera like a mirror) and its less obvious malleability.

This idea of the mirror of the cinema is based upon the deception of appearances, that is, upon the fundamental notion that real things stand for something else, more real than they are. The cinematic mirror is intended to reflect that hyperreality through the mundane reality of appearance. Mirrored structures allow a progressive building up of what is truly to be shown by using analogy to strip away the inconsequential from appearance.

Such an understanding amounts to a fundamental instruction for cinematic writing by defining in advance the essential nature of film language. “Good directing” comes to involve respecting and enhancing the properties of the cinematic mirror – and this would seem to be precisely what Weber set out to do. Her films are made of parallel, mirrored, constructions which radiate out from a central character or a group of characters. Such structures seep into and subtly deform the linear impetus of the narrative into a spiral, for in this kind of universe stories only end to begin again. If one character does something to protect his car from the rain, other characters will soon be engaged in the same activity, but in a significantly different manner. The fate of any character cannot be comfortably settled until each one of its aspects has been similarly finished off. In The Blot this involves gathering all the young men in the movie into one place at the end and paying each due attention so that the film forgets no one.

In order to produce an artful mirror through film making, as in other arts, it would seem that the obdurate materiality of the medium must be thoroughly tamed and trained lest it show too much. This surely accounts for the urgency of Lois Weber’s need to control all aspects of film production. But it is just this materiality that is the cinema’s own urgent truthfulness. The camera cannot lie, only those who wield it can. Thus the need for a preacher – a woman, a figure of unblemished honesty, l’ouverture – to take on that role. Two different truths are at war here – and neither can afford to recognise their difference or, indeed, that they have anything to fight about.

To illustrate this exigency of cinematic writing I can think of nothing more elevated than Harpo mirroring Groucho in Duck Soup. Together they dance the phases of writing Blanchot describes. And in the end, as we know from the beginning inevitably it must, a mistake reveals that the mirror is no mirror and all bets are off. That is, material reality, here the same as writing “outside language”, overpowers its “idealist” variant.

Let me try to describe the same process as it plays itself out over four moments in Lois Weber’s Hypocrites.[25]

At the beginning of the film a photograph of Lois Weber appears immediately following the last written credit, “BOSWORTH Inc. presents HYPOCRITES written and produced by LOIS WEBER Copyright 1914 by Bosworth (Inc)”.

Hypocrites: portrait of the author

This image acts as a kind of confirmation of what we have just read. But it is also, of course, A Portrait Of The Author. Written testimony to its authenticity is inscribed on its surface – “Yours, Sincerely Lois Weber”. It is a picture of a Woman, an authorising woman – one who writes and produces. But it is also a picture of a particular type of authorising woman, one who unmistakably embodies the authority of respectability. More than that, one who openly dedicates herself to us, one who urges her sincerity upon us in writing, as if we could not see it in her mothering gaze.

Here then, is this film’s first figuration of its director, a figuration heavily weighted with moralising significance. It will need all of that significance to counterweight the cinematic image it is about to display.

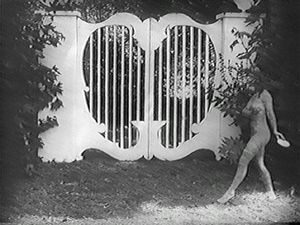

After an epigraph (“What does the world, told a truth, but lie the more’ Browning”)[26] and an intriguing, and disingenuously simple, display of the characters we are to see in dual roles, another title introduces a prologue, “The Gates of Truth”. These gates are shown, and in a moment, Truth enters.

In view of all I have written here (and leaving out of consideration the way in which Hypocrites itself deploys this figure), there can be no doubt that this naked woman with a mirror is also on some level a figuration of the cinema – or, at least, of the cinema as Lois Weber intends it. But there can also be no doubt that this figure raises questions of another order for film maker and audience alike.

In 1974 Kathleen Karr described a device used in exploitation cinema that she called “the square-up” and which she had traced back to 1912.[27] The square-up at its crudest and most direct is a “prefatory moralistic statement of apology for contemplating the discussion of nefarious subjects” (108).

The “square-up” soon became a stock element of practically every example of the silent exploitation film. It was very much of a protective device and most interestingly foreshadowed the Supreme Court’s later guide-line decision on obscenity (regarding Lady Chatterly’s Lover) that in order to be obscene a work must be “utterly without redeeming social importance.” (109)

Later in the piece, Karr quoted a classic square-up, prefaced to Weber’s 1916 feature, Where are my children? (124-125). Given the history of the device, I think that there can be no doubt that Weber’s Portrait Of The Author in Hypocrites is intended to square-up the figure of Truth, whose nakedness is both a literal and a symbolic issue for the film and who appears many times in it.

Thus the sign of the female enunciator, a sign exploited even more elaborately later by Mrs Wallace Reid in films like The Red Kimono (1925), is also a sign intended to cleanse the film, to absolve it of prurient intent. The image of Woman, conventionally only a figure created by and for male lust, acts to purge that lust before it has even been called forth. It is as though the authorising photograph of the cinematic writer as Woman is intended to be seen in front of the metaphorical figure of naked Truth as Woman, a lens or an opening through which the truth of Truth can be discerned. Put in another way, the introductory picture is far more than simply a sign of a woman’s authorship. It is a sign which, however naively, proclaims that a woman’s vision – a woman’s cinema – is different from a man’s.[28]

And such devices change the ontology of the images we see, animating them differently. A sermon does not merely preach about the wickedness of the world, it reflects that wickedness back upon its auditors – making them party to it, making them guilty as it offers its vision as a means to repentance. Which is to say that the sermon’s re-vision of the world, its deregulation of the senses, is the first step to changing the state of those who hear it. A sermon turns pleasure into displeasure and vice-versa. In a sermon, the sense of the world shifts, and the old world makes new sense.

Or does it? Can l’ouverture which Weber makes of herself force everyone to see through Margaret Edwards, the naked woman on the surface? The answers are obvious, and were obvious even when the film was released, as the controversy around it demonstrated.[29] The obstinate, everyday materiality of the cinema, its goes-without-saying literalness, registered the naked Margaret Edwards as the naked Margaret Edwards. Those who were so minded could abstract that specific, meaningless image from the sensational figure Weber intended to make it mean and instead create their own lubricous figures, equally, if not more, meaningful and sensational.

This means that the cinematic author whose rather smug and serene portrait underwrites the film turns out to be something of a pathetic or tragic figure after all. And indeed, as the figure of the Truth-teller enters the diegesis – which is to say, as the narrative begins – the haunted futility of its mission becomes apparent.

This figure is a man. Weber has unsexed herself in a commonplace way, as she did in describing what a director does – but also to rather more drastic ends, as we shall see in due course.

That this figure is nonetheless at least partly intended to stand for the director herself is apparent from what it is doing in its first appearance: preaching a sermon to a more or less inattentive or discomfited audience. Moreover, the written text of the sermon (Matthew 23.28) has preceded the minister himself, summoning the scene and his presence in it, as the line from The Ring and the Book summons the figure of Truth.[30] This is a figure of words or of writing, a cypher, a trope – not intended to read as itself (indeed the character has no name, only a title).

This scene of speaker and audience recurs nightmarishly in Weber’s work.The Blot opens with an emaciated, dedicated older man speaking to (teaching) an audience of inattentive younger men. In Too Wise Wives society women are shown attending a political lecture given by a man to whom they pay no real attention. In The Hand that Rocks the Cradle (originally titled Is a Woman a Person?), campaigners for birth control, one of whom is played by Weber herself, are arrested before they can complete their speeches. In each of these figurations, words fall on deafened ears, a speaker’s gift is scorned or balked. The compounded vision is one of infernal torment that surely would be mete only for the most notorious sinners of classical mythology.

In Hypocrites the minister turns from his hypocritical congregation to the visionary pursuit, and capture, of Truth herself. “Since my people will not come to you, come to my people,” he importunes. In his vision, he brings Truth back into the world, but not as an object of display – rather, as the means by which he is enabled to see beneath outward appearance and into inner Being. Under his instruction Truth holds her mirror up to a list of everyday scenes that might have found a place in Borges’ Chinese encylopaedia:

* Politics

* Society

* Love

* The mote in the eye

* Modesty

* The home

and Truth’s mirror shows the hypocrisy of each, displaying to him, and to us, the invisible evil behind the bland surface of convention. In the simplest possible fashion, life’s mirror, the cinema, has been passed from the director to her surrogate in the text – along with the author’s mission to expose what cannot otherwise be seen. The minister then moves through life like a television reporter shadowed by Truth in the role of his video camera operator: in a circuit our eyes, his eyes, her eyes.

And there is no scene that is not evil, there is nothing ordinary behind the ordinary – only deception, corruption, deception, sensation: lurid, all-too-lurid figures. This reflected world cannot satisfy the desire of one who has seen Truth as she is. Such a soul can find peace only the realms of Truth herself, behind the gates where all the unborn babies live.[31] Thus the minister dies and the hypocrisy of the world lives on.

Hypocrites: “but lie the more”

In the list of scenes in which hypocrisy is revealed in the mirror of Truth, one is marked by its titular difference from the rest.”The mote in the eye” is no clear kin of “Society” or “Modesty”, and that is because the hypocrisy that it figures is of a radically different order.

Each of the scenes has re-visioned members of the minister’s congregation, representatives of mundane hypocrisy: a rich man, a society woman, a pretty young woman, a philanderer, a young family. These are the people faced by the minister in the opening scene – those at whom he gazes and who return his gaze. The object of “The mote in the eye”, although also in the church, is not someone at whom the minister looks. Rather, from the choir stalls behind and to one side, she looks at him. She looks at him in adoration. Throughout his vision, she goes where he goes. In a long allegorical sequence set in mediaeval times, she continues to gaze, enraptured, at him and at the figure of Truth that he sets before the people.

And this scene exposes the hypocrisy of her seeing, the mote in her eye (but not the beam in his). If it had not been obvious before, in this scene it becomes obvious that the shape of Truth’s mirror is the outline of an eye – for what the mirror now reflects is another eye, the voyeuristic eye of this woman, an eye that gazes in a circuit of her eye, his eye, truth’s eye, our eye.

But something (not a mote, I think) is also reflected in her eye. Her eye is also a mirror, a mirror now one with the mirror of Truth. But her eye is not a blank. There is something caught by the cinema in it. As the figure of naked Truth dissolves away, it begins to reflect (inadvertently?) a motion picture camera and a man cranking the camera. Her eye shows the cinema where we know truth to be.

Almost before that reflection has been fully absorbed (and certainly before one can decide whether it is”deliberate” or a “mistake”), another image is superimposed upon this eye that reflects the truth, that is the mote. It is the face of the minister, and it is not unlike a skull.

When he recognises the image in her eye, the minister gestures his revulsion and departs with Truth and the mirror, leaving her alone, looking at nothing.

There can be no doubt that he is the mote in the eye that hinders her sight. Her hypocrisy has been to pretend to love the Truth when she loves only him. In effect he spurns her because she has misrecognised him, mistaken the outward form of a man for the inward, invisible aspiration, the body for the spirit, nakedness for Truth. And if in some way she stands for all of us in the audience, he and Lois Weber spurn us too, insofar as our love for her cinema of truth, for the cinema, is only, as it is in my case at least, a love for what it is and not for what it would like to be.

But it is somewhat harder to reflect on the image of the camera operator we have seen – the later-to-be-famous man with a movie camera (who is also reflected in a woman’s eyes in Vertov’s film of that name). In two senses the camera operator (Dal Clawson? George W. Hill?) is another figuration of the cinema. First, he figures the cinema in his aspect(the camera), as the figure of Truth does in hers (nakedness). Second, his appearance is a result of the materiality of cinema, throwing us outside idealist and moralising language just as Margaret Edwards throws us outside language with her body that cannot be inscribed.

If this is an accident – if it is, as I take it, an instance of a naive relation with the cinema – it is nonetheless, and inescapably, a moment in which a certain sublimity is articulated that “good directing”can never know, a moment in which the world is made sense by the cinema, sense manifests, rises up, is born to presence, where before there was only appearance and meaning. It is a moment one lives for.

Where is the camera? The image of the minister is in the choir singer’s eye because it is in her heart. The image of the camera seems to be in her eye because it is in the mirror – the camera is the heart of the mirror. Yet the point of Hypocrites is at least partly that Truth has no human heart, no place for love. Here, as elsewhere (in Lacan for example), the mirror is cold, lacking feeling, as austere as the rejecting minister who does not recognise the beam in his own eye. And indeed, the heart of this mirror is not human, but a machine, a mechanical heart whose beating corresponds to the frames of the film it registers without compassion.

In this image, the minister overlays the machine: an unfeeling other overlays another, equally unfeeling, and equally dedicated – in the middle of what can only be described as a pool of love. The love spills out, beyond the face at its focal point, suffusing the machine, contaminating the mirror. And we can see what the minister cannot. That he is driven by his lack, as she is by hers. That his ascetic desire for absolute nakedness dooms him in this world – and that what might redeem him to life is here, exscribing its finite longing in the mirror, transforming the mirror and the cinema itself if only for a moment.

A blink of her eye.

6. Appendix: Lois Weber’s surviving films

This essay has been based on a very few films – those three features which I could view and review during its writing: Hypocrites (available in a restored version through Kino on Video [http://www.kino.com/newstuff/firstladies.html] and in a 16mm print taken from the Australian original print held by Cinemedia Australia [http://www.cinemedia.net/]), The Blot (available through Mediabay [http://www.mediabay.com/]) and Too Wise Wives (available in a tape called”America’s First Women Filmmakers” for purchase in the Library of Congress Video Collection distributed by Smithsonian Video [gopher://marvel.loc.gov/00/research/reading.rooms/motion.picture/sales/vidsale]). I understand that a print of Where are my children? has been screened on the Turner network in the United States.

Anthony Slide suggests that at least some material from 17 Lois Weber titles has survived. Some he mentions as having been preserved in the Library of Congress: A Japanese Idyll (1912); False Colours (1914 incomplete); Hypocrites (1915); It’s No Laughing Matter (1915 incomplete); Sunshine Molly (1916 incomplete); Shoes (1916 incomplete); Discontent (1916); Where are my children? (1916); To Please One Woman(1920); What’s Worth While? (1921); The Blot (1921); Too Wise Wives (1921); A Chapter in Her Life (1923); The Marriage Clause (1926 incomplete). He lists Suspense (1913) as having been preserved in the British National Film Archive. Two others he describes as though he has seen them, and I assume they exist somewhere:The Dumb Girl of Portici (1916) and Sensation Seekers (1926). Kevin Brownlow says that a variant, “European version” of Where are my children? also exists. [32]

Endnotes:

[1] I must thank Adrian Martin twice. First for asking me to write about Lois Weber, and second for his patience while I did (not). I must thank Deb Verhoeven for giving me the opportunity to teach a course based on Hypocrites. I must thank Cinemedia Australia, where I watched and rewatched the Australian 16mm print of Hypocrites, and the AV staff at the La Trobe University Library, who are always so supportive and understanding. I must thank Caro again for her patience in getting this ready for you to read. I must thank Anthony Slide, Jennifer Parchesky, Maurice Blanchot and the invisible Jean-Jacques Lecercle for having written so eloquently and telling me so much I did not know and Jessica Rosner for her work in restoring Hypocrites for video release. But this article is dedicated to Andrea and Anna and Eloise and Kathy and Peter and Sam – and, always, Diane.

[2] Maurice Blanchot, The Infinite Conversation, translated by Susan Hanson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), xii. All the other quotations in this section come from the location cited.

[3] Tom Gunning, The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity (London: The British Film Institute, 2000).

[4] Alexandre Astruc, The birth of a new avant-garde: la caméra stylo“in The New Wave: Critical Landmarks selected by Peter Graham(Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1968), 17-24. Published originally in Écran français 144 (1948).

[5] Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tarzan at the Earth’s Core (London: Mark Goulden Ltd., n.d.), 65.

[6] Apparently the poet, known as”the sweet singer of Michigan”, used this sentence in the preface to her last volume of verse, A few choice words to the public with new and original poems by Julia A. Moore, published in 1878 (see The stuffed owl: an anthology of bad verse, edited by D. B. Wyndham Lewis and Charles Lee [New York: Capricorn Books, 1962], 233). A very wise critic once cautioned me against using Moore’s phrase as the title of an essay because it was not at that time politic to claim to be writing literature.

[7] Anthony Slide, Lois Weber: The Director Who Lost Her Way in History (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996), 67.

[8] Slide, 46.

[9] Carl Laemmle, qtd. in Winifred Aydelotte, “The little red schoolhouse becomes a theatre,” Motion Picture Magazine (March 1934), rpt. in Slide, 5.

[10] Alice M. Williamson, Alice in Movieland (London: A. M. Philpot Ltd., 1927), 231.

[11] Lois Weber, qtd. in Mlle. Chic, “The greatest woman director in the world” The Moving Picture Weekly (May 1920), rpt. in Slide, 57-58.

[12] Ethel Weber, qtd. in Elizabeth Peltret, “On the lot with Lois Weber” Photoplay (October 1917), rpt. in Slide 32.

[13] Lois Weber, qtd. in Aline Carter, “The muse of the reel”, Motion Picture Magazine (March 1921), rpt. in Slide, 29.

[14] On which see Sumiko Higashi,Cecil B. DeMille and American Culture: The Silent Era (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 142-178.

[15] Lois Weber, qtd. in Bertha Smith, “A perpetual leading lady”, Sunset (March 1914), rpt. in Slide, 37.

[16] Lois Weber, qtd. in “The Smalleys have a message to the world”, The Universal Weekly, 10 April 1915, rpt. in Kay Sloan, “The Hand that Rocks the Cradle: an introduction”, Film History 1, no. 4 (1987): 341.

[17] The events summarised in this and the preceding paragraph are covered in Slide, 19-45 and passim.

[18] Lois Weber, qtd. in Peltret (see note 12), rpt. in Slide, 21. The same story apparently occurs also in Smith (see note 15), but perhaps not in the same words.

[19] Slide, 64. He cites only Memories (1913) and Even as you and I (1917), which was produced at Universal, but released as the first “Lois Weber Production” (105-106).

[20] Slide, 37.

[21] The issue is the one for April 20, 1921 and the articles cited are “Impoverished college teaching”and “Boycotting the ministry”. See Jennifer Parchesky’s excellent analysis of the class politics represented in the film, “Lois Weber’s The Blot: rewriting melodrama, reproducing the middle class”, in Cinema Journal 33 (1999): 23-53.

[22] Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley, Is a woman a person? [The Hand that Rocks the Cradle], Film History 1 no.4 (1987), 363. The text is the release continuity of a film that is lost. Subsequent references to this film are also based on this continuity.

[23] See Slide, 74-76.

[24] Parchesky, 34.

[25] There is some doubt about the correct title of this film. Anthony Slide, Kevin Brownlow and the scholars of the American Film Institute have called it The Hypocrites. At least one surviving publicity still is labelled Hypocrites!. I take the title from the opening credits of the 16mm print currently circulated from the Australian National Film Collection by Cinemedia Australia and which has provided the basis for the research for this article. That print was struck from a 35mm print originally held in the Australian National Film Archive which is the single most complete original print of the film and is, I think, of the earliest release (1915). The same title is used on the videotape restoration produced recently by Jessica Rosner for Kino On Video, which makes use of material from the later (1916) release version as well as the Australian material. Both these sources also correct both Slide’s and the AFI’s divergently inaccurate plot summaries

[26] In the new video restoration of the film, which uses some material from the version re-released in 1916, these words from Browning are dissolved over Weber’s portrait, over-writing and further authorising it.

[27] Kathleen Karr, “The long square-up: exploitation trends in the silent film”, Journal of Popular Film 3, no. 2 (Spring 1974): 107-128. Further references to this article appear as page numbers in brackets in the text.

[28] For what it is worth, Weber and Smalley are credited as working together on five of the seven Bosworth films. Weber alone is credited on It’s No Laughing Matter and Hypocrites, released within a week of each other.

[29] See Slide, 72-74.

[30]This is not the case in the restored video version, in which we see the minister preaching before we know the text of his sermon, but it is the case in the 16mm print based on the version found in Australia.

[31] Such a gate is apparently figured at several points in Where are my children? See the discussion of the film in Kevin Brownlow’s Behind the Mask of Innocence (New York: Knopf 1990), 50-55.

[32] Brownlow, 50.