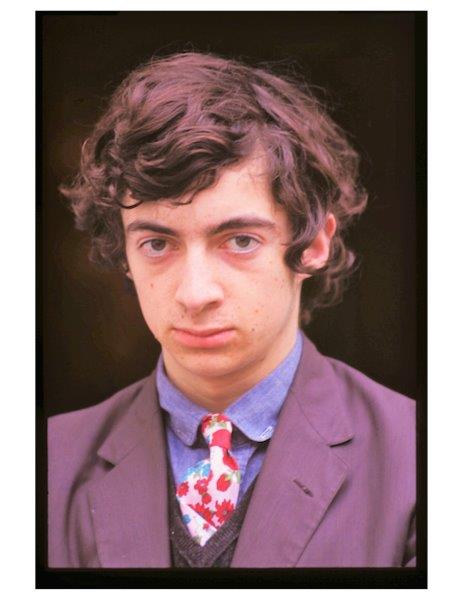

Philippe Mora, aged 18, in London soon after having left La Trobe University in late 1967.

Year one at La Trobe for me was 1967, and it was literally a wild year. Some friends from University High joined me in the brand new campus for what was going to be a romantic adventure (or so we hoped). This included my girlfriend Freya Mathews. While making out with Freya one day in the surrounding bush I got a tingling sensation in my butt. When this turned to acute pain I found myself lying on a nest of vicious, angry red ants. She went on to write brilliant books on ecology.

Nothing radicalizes students faster than pointless police brutality, and in 1966 the Victorian police, Deputy Premier Arthur Rylah and Premier Henry Bolte were really good at radicalizing Melbourne’s youth. They were the Viet Cong’s best friends. Every time one of their cops hit a kid on the head (I was hit, for example), the anti-Vietnam war movement gained passion. Violence against children is simply unacceptable. And we were kids.

US President Lyndon Baines Johnson visited Melbourne in October of 1966. Some of us Uni High students threw eggs at his limousine as it drove by, and we unfurled a long poster that read, “HEY HEY LBJ HOW MANY KIDS HAVE YOU KILLED TODAY?” My mother MIrka helped us paint it. The next day at school the principal sternly warned us not to throw eggs or protest in school uniform!

In January 1967, South Vietnam’s gun totin’ whacko Air Vice Marshal, Nguyen Cao Ky visited Melbourne at the invitation of Prime Minister Harold Holt. In 1965 Ky had said he “only has one hero – Hitler” (sic). Meanwhile, The Age reported that Labour leader Arthur Calwell called Ky a “little Quisling gangster”, a “miserable little butcher”, and a “moral and social leper”. For us young students all this made for a heady mix. We protested (not in school uniform) Ky’s arrival for a dinner at Government House in the Royal Botanic Gardens. It was dramatic film noir. Darkness and flashing lights, dogs and yelling. Police went nuts, like Les Patterson on acid, chasing us through the gardens. I escaped injury that time but not terror.

This was the explosive political background to my first year La Trobe University. Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove (1964) had already radicalized many of us culturally in 1964 by showing us that leaders simply could not be trusted. Kubrick planned to move his family to Perth to avoid nuclear war.

I started the La Trobe Film Society and we screened classics in 16mm. I introduced Otto Preminger’s In Harm’s Way (1965) and the audience laughed uproariously to my puzzlement, until someone yelled out that my fly was undone.

I put out the first ever issue of Cinema Papers (my title translation of legendary Cahiers du cinéma) with an after hours guerilla printing operation in Professor Wolfsohn’s office. He later commended us for the magazine, and attended the auspicious launch at the East End Bookshop, Exhibition Street, hosted by John and Sunday Reed.

The cover featured the bleeding nurse from Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1926). We also published Sugar in the Head at La Trobe, a student paper with an anti-war theme and cover art.

My cohorts and I created Cinematheque Discotheque, a riotous rock concert night with movies, and bands including Jeff St John and the Id. Turnout was huge and we had literally barrels of cash.

I then made Give It Up (1967), a 16mm short film about apathy. Shot in Acland Street, St Kilda, outside the Tolarno Bistro, it starred some La Trobe team – Don Watson, Demos Krouskos and Howard Willis. Sweeney Reed and my kid brother Tiriel Mora also featured. The NFSA summary for the film reads: “Symbolic of Australians’ response to the Vietnam War, a man is repeatedly kicked and beaten in a busy street while onlookers do nothing.”

Then it was ‘Bye Bye La Trobe University’ for me. I went to London in late 1967 and was startled to see that what we thought was radical, like opposing the Vietnam War, was mainstream thinking in much of the British press. It was okay to be against the war. You would not be chased by police!

But La Trobe was still in my blood and I made a sculpture out of raw meat as a protest to man’s inhumanity to man. This prompted a royal complaint about a bad odour in Covent Garden … but that’s another story. The story of La Trobe in the subsequent years continues here, in the following dossier, Radical Beginnings.