(The original manuscript of Kinopraxis is published here with the kind permission of Bertrand Augst.)

Table of contents

1

The contribution of J. -L. G to the Week of Marxist Thought on the theme “Film and event” at Besançon in December 1967, printed in La Nouvelle Critique #199 (November 1968) as “Un Prisonnier qu’on laisse taper sur la casserole”.

2

Extracts from text, in French, representing a talk “on the work of the filmmaker” by J. -L. G. and Michael Cournot at Nanterre “before students” in 1967 at some time textually “three weeks” prior to the start of filming for La Chinoise, printed in Revue D’Esthetique XX, 2-3 (April-September 1967) as “Quelques evidentes incertitudes”.

3

Taped in San Francisco by Joris Svendsen, Tom Luddy, and David Mairowtiz, March 1968, printed in San Francisco in Express Times, 14 March 1968, as “Talking Politics with Godard”.

4

Extracts from text, in German, taped in Paris in August 1968, printed “as nearly verbatim as possible” in Film VII, 4 (April 1969), as “Die Kunst ist eine idee der Kapitalisten”.

5

Extracts from text, in French (which seems taped), published, undated by J. P. C. and Gerard Leblanc in Cinéthique #1 (January 1969), as “Un cinéaste comme les autres”.

6

Text in French, dating to March 1969, representing the sound accompanying image shot by a person or persons as yet unknown to the editors for French television, specifically for a show or a series titled Cinéma Six. The image reel bears the hand-written date “I. P. N. ‘Cinéma 6’ Journes 19 mars 69.”

7

Text in Italian, taped in Paris at an unspecified date by Paola Rispoli, printed in Filmcritica #194 (January 1969), as “Cinema provocazione”.

8

Taped in London by Jonathan Cott. Undated. Printed in Rolling Stone #35 (14 June 1969), as “Jean-Luc Godard”. Copyright 1969 Straight Arrow Publishers, Inc.

9

Text printed in Cinéthique #5 (September-October 1969), as “Premiers ‘Sons Anglais‘”. Signed: ON BEHALF OF THE DZIGA VERTOV GROUP: JEAN-LUC GODARD.

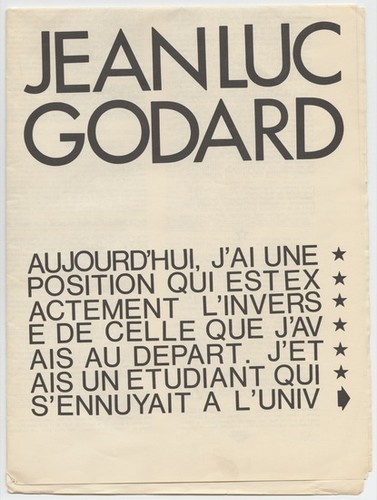

JEAN-LUC GODARD was first published as No. 0 issue of a “news & text broadside” called Kinopraxis on the occasion of a screening of Jean-Luc Godard’s See You at Mao (British Sounds) in Berkley in 1970. The translations were prepared by David Deneger, the texts were selected and edited by Bertrand Augst and David Deneger, and printed under a rubric dating to May ’68: Liberez l’Expression.

© Bertrand Augst & David Deneger 1970

JEAN-LUC GODARD

1

My position today is exactly the opposite of the position I took at the outset.

I was a student and I started to get bored with the university, the way a lot of them do as soon as they’ve gotten their degrees (leurs bacs), who got their degrees without any clear idea why they were working to get one, and don’t know what to do with the time on their hands. I got out of it through my encounter (I don’t know now quite how it came about; I was about twenty) with film, I mean with what I’m now calling image and sound. I was wanting to, I was tempted to make them myself, images and sounds, to talk about them … I met some guys in pretty much the same situation as mine, who came from pretty much the same background as mine, and so … we were wanting to get into this French universe of image and sound. We found out then how closed it was. We didn’t know why, we didn’t know how. I didn’t even know what the words “Marxism” and “capitalism” meant. I was twenty years old, I admit, but, as I’ve told you, I’d been raised in a bourgeois universe. So what we did was, we wrote at first more or less for ourselves. We showed films. We started a film-club in the Latin Quarter. We attempted to publish little movie magazines of our own with the money we had saved, so we could talk about the movies we liked and criticise the ones we didn’t. We hadn’t thought yet about making movies of our own, because we didn’t know how they were made. It took seeing a lot of movies to learn that movies are made in labs, with a camera (!); that the raw stock is manufactured by Kodak; that the magnetic film is manufactured by Agfa; that the sound is recorded by microphones; and that you have to have money if you want to make films. We started to make little home-movies, with money from our savings or out of pocket. I stole right and left in my family to get enough money to make movies, I mean to try first to make images and later to make sounds, too. Sound cost much more then. A roll of sixteen-millimeter reversal film black-and-white cost 50,000 old francs, which, for a student who was always broke, was really a lot of money. Little by little we became critics. We shouted loud enough to be heard and, as time passed, we were increasingly less isolated, for (for example) the Cinémathèque française came into being around that time, too. I became a critic. Then I made some short films. Finally I made a feature. I made one, two, three, four … Today, having made fifteen features, I realise then I’ve come into … If you like, I used to think of the thing we used to call “traditional French film” as a fortress, which had to be taken by storm. I see now that I did in fact succeed in taking it by storm. I occupy it now: I’m its prisoner. Maybe it’s true that I’ve succeeded in destroying some things in film … in one particular way of making film, but I’m aware now, you know, that I’m free but still I’m a prisoner. I’m the prisoner, if you like, banging his dish on the bars of his cell. They let him make all the racket he wants. Three out of four traditional directors (metteurs en scène) (and I think of myself as one of them, too), in Moscow or in Hollywood, are stuck in a prison somebody else made. They don’t even know it’s a prison. I do, at least. Inside the prison I’m free to do as I please, but still I want to get out. And that’s where I place the link between the creation and the distribution of film, because up to now I’ve only been thinking about the creation of film. In some sense, I have made a complete circuit of myself and now I’m back to what I began with. From the point of view of creation in film I find myself forced to restructure my language, to get back to the basics. Higher mathematics have been enabled to make new discoveries through a radical re-examination of the basic elements of arithmetic and geometry, and modern philosophy as a whole is in the process of rediscovering, re-examining language from the point of view of its grammar and the philosophy of grammar. I think that I’ve got to get back to these basics, and that is where the creation and the distribution seem to me to be closely linked, for if the creation is at a stand-still it is because it’s run into a blank wall, it’s because movies have been … are being distributed in ways that do not now allow you to reach the public as you have to reach it. This is the second time I’ve come to Besançon [1] ; if I keep coming back, it is because something is in the works here; people have decided that … it’s not going to happen in months; it’s a question of years but – two or three people who make movies in Paris are trying to think about the work it takes to make movies, in collaboration with workers in Besançon who will be thinking about artistic creation in terms of the work they can do themselves. Everyone will be thinking about it in terms of the work he does himself, but everyone knows it concerns him as directly as anyone else. I hadn’t realised it till now. I hadn’t known how much I needed it till I realised that I’ve run out of breath when it comes to creation in film. I think it’s a need that all young filmmakers now feel (and youth is not a question of age), I mean, everyone who is interested in seeing film that is truly independent, because film, of all the arts, is always the most enslaved, economically and culturally enslaved. The simple fact that you are still going to see movies in theaters is clear proof. There is really no reason why movies should have to be shown in theaters. They can be shown in your own home; that’s what television is; the problem of film, I think (this needs to be said), is inseparable from the problem of television; there should be one single word for them both, for what I call image and sound. The electronic distribution of image and sound is called television; the photographic distribution of image and sound is called film; but it’s obvious that film as we know it … the screening of movies in theaters accounts for no more than twenty or maybe even ten per cent of the total market. The amount of film Kodak manufactures for use in the industry is only two or three percent of the amount it manufactures for use by amateurs. Anyway, I think that the future for the professionals in film lies in the amateurs, in taking the word in its broadest sense.

[Text in French, representing “the contribution of J. -L. G. to the Week of Marxist Thought” on the theme “Film and event” at Besançon in December 1967, printed in LA NOUVELLE CRITIQUE #199 (novembre 1968) 62-63 as UN PRISONNIER QU’ON LAISSE TAPER SUR SA CASSEROLE. English text copyright 1970 by Jack Flash.]

*****

2

I discovered film very early, in the film-clubs in the Latin Quarter which is where I was spending my time since the lecture-halls at the Sorbonne were (already!) so full you couldn’t get in. And I had many long talks about movies with friends of mine like Truffaut and Rivette, who were just getting into it then. So what I did was, I hung around a lot, I gave them a hand now and then, I learned something about the technical side of film. That’s what I was doing for ten years before I made my first movie. And when I made my first movie, I had no idea where I was headed, I had no dogmatic views about anything. Anyway, I had the feeling, confronting this world of producers and artists, that I was a child. It took me a long time to realise that it was I who was the adult, and that the difficulties came from its being children who finance and run the film industry. It is only now, after fifteen movies, that I have some sense of where I stand. This is involved with the feeling I have that my youth is behind me now: I just don’t have the enthusiasm I had when I signed my first contract. I’ve been lucky in my relations with producers: I can do pretty much what I want; but I still have the feeling (it surprises me still) that it’s been like a punishment or kind of purgatory. In any case, when I got started in film I was not hampered by definitions; definitions didn’t interest me, the way they do philosophers, and maybe some other kinds of artists, too. All I had was image and sound.

Despite what I was saying, I haven’t any better idea where I stand than you do. In three weeks, I start shooting a film that has what is theoretically a very well-defined subject: the view students have of Chinese-Soviet relations today, but I just can’t get into it. I read L’Humanité and Le Monde every day, but I never feel really enlightened or moved to action, so I’m going to have to just jump in without being able to say in advance what swimming is or even the water you swim in. If it were possible to single out a few specific ideas about film, to state a few general principles, I feel it would help me. But I believe just as firmly that this is impossible. When I heard (Roland) Barthes talking about film at a round-table recently, I felt I was listening to somebody’s grandfather talking to his kids about life: “I’m telling you this for your own good … ”

Can you teach film? I don’t think so. You can teach Algerians how to work a tape-recorder, but they’ll have to find out how to make effective use of it themselves. It’s like some kid coming to ask me if he can watch me shoot. I ask him, “Where do you live? Is there a church near you? Is there a Woolworth’s (un Prisunic)? Make a movie about the Woolworth’s with the money you can save. I can give you a little advice about making it, but watching me shoot, me or Clouzot or Hitchcock, it isn’t going to teach you a thing.” Still, I have never been able (in which the men on the Cahiers are just like me) to separate action from reflection, though many who make movies can. But when I reflect it’s almost automatically and it’s always short-lived. If I really have to, I can talk about myself making movies but I cannot define film, any more than I can define music or painting, for example. If you are waiting for me to give you pat answers or ready solutions, you are going to be disappointed.

I am committed, yes, because it has been film that revealed life to me. In the beginning, it kept it hidden. I mean, I had enough on my hands just fighting the system with a few buddies of mine (camarades), trying to make my own little revolution – I still remember how calm I felt May 13, 1958 at Cannes – but after a while it started to go in the opposite direction: it was in making Le petit soldat (1963) that I discovered the war in Algeria, and today it is life that’s revealing movies to me. I am certain it was the Ben Barka affair [2] that got me going on Made in USA (1966). I am quite well aware that a movie is never going to solve a problem. If I were a baker, I’d be writing PEACE IN VIETNAM on my loaves, but I’d know it wouldn’t put a stop to the fighting. You have to be yourself first, at least if you’re interested in having the public become aware of a problem. If none of the recent Russian films has done any real harm to American imperialism, it is because the one ambition of the Russians who make movies is to imitate the Americans. But, as it happens, when Pierrot le fou (1965) was screened in Hollywood (in 1966) in connection with the thing they have there with the Oscars, they stopped the film at the point where Belmondo and Karina do the sketch on Vietnam.[3] They simply refused to consider it. You see, they took it for what it was. But in France they said I’d used somebody else’s real war just to make a bad joke. It was the same way with Les carabiniers (1963): it passed unnoticed in France, but (in Algeria), when it was shown at the film-club in Tlemcen, the people recognised it as their own war. Nothing has ever given me greater pleasure – you can call me a left-wing anarchist, if you like.

The notion that there is some real difference between “commercial film” and “intellectual film” is completely false; it’s the invention of people who want to keep certain films in the ghetto. When I was in Algeria, one of my movies was shown at the Cinémathéque there. A real “popular” audience mostly young people (not students, though), who showed somewhat more respect than you usually get from the young, because they were aware that they had a Cinémathéque only because people had worked hard to get one. I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to be there during the screening or not, because it had some literary quotations in it … Even a little Heidegger. But I listened to the dialogue and it flowed as smoothly as water. Even the quotations seemed free from the guilt that seems to attach to their being quotations; Being, Nothingness, it was all perfectly clear … But the great masses of French are terribly well-conditioned, and no one seems even to notice. I’ll give you an example. (Albert) Cervoni[4] published a very harsh review in France Nouvelle of La grande vadrouille (Gérard Oury, 1966). Some readers in Lille wrote a letter in protest. They said, “But we have the right to laugh, after a hard day at work.” The editors took sides with the readers, against the reviewer! I still criticise the (French) Communist Party for limiting its activity in film to denunciations of American movies; it hasn’t tried to create a real film culture here, which is what Lenin did in Russia. Still, Cervoni is right when he says, “I’m not saying that you don’t have the right to laugh, but laugh at Chaplin or The Suitor (Le Soupirant, Pierre Etaix, 1962), because if you laugh at La grande vadrouille, you’re betraying yourselves.”

[Extracts from text, in French, representing a talk “on the work of the filmmaker” by J-L. G. and Michel COURNOT at Nanterre “before students” in 1967 at some time textually “three weeks” prior to the start of the shooting for LA CHINOISE, printed in REVUE D’ESTHETIQUE XX, 2-3 (avril- septembre 1967) 115-122 as QUELQUES EVIDENTES INCERTITUDES. English text copyright 1970 by Jack Flash.]

*****

3

I got my political conscience at 35 (instead of 15). Maybe it’s because, all around the world, the movie industry is completely separated from real life. I wanted to do a movie and I had to enter this very peculiar world. But when I was in I had to fight just to make a movie because we were not accepted. After having succeeded in making a few movies, I discovered that what I was doing was coming from something unreal. I felt I had to make new movies in a different way. In the process of trying to make new kinds of movies, I discovered imperialism from an aesthetic point of view.

What is imperialistic about the movies up to now, in their form?

It’s a group of people who want to oblige other people to make movies their way. Look at Africa, for example. They are not able to make even one black movie. They have only white movies. Even in Guinea, which is rather revolutionary. Even in Algeria – they are trying, but it’s very difficult for them. Because they can look at films on TV. All over the world, TV is only a “show” with commercials. Even in Cuba, the TV is still completely American.

Is there anything about film production that you would call reactionary or imperialist?

It’s a way of telling people: this is the right way to make a movie, and if you don’t do it this way, you won’t be able to exhibit it. If there is an imperialism in production, it is an aesthetic imperialism.

Could you elaborate on that? For example, I liked, in your film, Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her, 1966), your point about the “gestapo of the structures.” Could you describe the gestapo nature of film production?

If I use this expression, it’s because one structure’s been imposed and all the others eliminated. Just now, I don’t know what a structure is and I’m trying to find out – I discovered American cinematic imperialism when I signed a contract with Columbia. I physically experienced at 35, what a black man in Africa must feel much earlier.

In what way is it possible for any art form to influence immediate action? Is it possible to prevent, for example, what’s bound to happen in this country? Is it possible to reflect it?

Not to reflect it, but to work in the same direction. You can make a movie or a painting that will say exactly the same thing as Stokely Carmichael.[5] But this will not necessarily be a picture of violence. Let’s take a painter like Matisse, who was a member of the French Communist party. He never went to war, so he painted flowers all his life. But his paintings, in one way or another, were going in the right direction.

Specifically, I mean, where can a filmmaker show any direct influence?

Specific influence – when he’s speaking on TV or making a documentary. In real life, though – when he’s not making movies. Then he does as everybody else does.

Would you say that a movie like Far from Vietnam (Loin du Vietnam, 1966) can in any way have any real significance and, ultimately, some real effect on the war?

Yes it has. But, as the North Vietnamese say: Any time you say the word “Vietnam”, just say the word, it helps us. And that’s what Castro said at the end of the Cultural Congress in Havana. He said, to European intellectuals: Just try to work and speak or make paintings and it will help us. As long as you are doing it.

In Far from Vietnam, there is a sequence where you say you wanted to go to Hanoi and they turned you down. You say you feel that if you had gone, you might have done more harm than good. Is that true?

Maybe. Because I don’t know exactly what I should have done. It’s like that La Fontaine fable: a bear wanted to scare a fly away from the forehead of his master, so he threw a great stone at it, and the master died.[6] With the North Vietnamese I didn’t know all the implications. They could be distrustful of people, and perhaps that’s why they didn’t invite me. They didn’t know me. I might think I was doing something good, that would turn out bad.

So then, your reluctance is because you don’t think you could make the right film out of it?

Yes. It’s like when they try to make so-called “left” pictures in Hollywood, like Salt of the Earth (Herbert J. Biberman, 1953). This film is only shown to people who are already convinced, in Communist meetings. They show the film at the end of a meeting, and it’s just like listening to a record you like very much. Like a speech in a Congress, after which everybody applauds, but it makes no difference because everybody knows what’s going to be said. Just now they are preparing, in Hollywood, a picture about Malcolm X, for example. Script by James Baldwin. In my opinion, if such a movie were a success, it would have to be banned in the United States. The fact that it’s not banned is the proof of its not being any good.

And Tony Richardson’s making a film about Che Guevara.[7]

I’d like to continue speaking about art. But maybe we shouldn’t, because now it’s reactionaries who only talk about art. Art is a normal everyday activity. It’s not an extraordinary one. What must be done is to show art as an everyday activity, like sports. It’s precisely the reactionaries who try to say that art is something out of the ordinary, something special. So they pay well and try to give artists a luxurious life.

In a Socialist society, it wouldn’t be that way.

No. They hope not. But in Russia, it still is.

In Cuba?

Yes, they are trying, but it’s very difficult. In China, they are. But it will take them years and years.

Would you say that in China they have found their artistic language?

Oh no. Not at all. Mao said: A piece of art which is politically just, but which fails from an artistic point of view, is bad. But the contrary is bad too. Bad politics and good art is bad too. This is very clear, but this is very hard for them to do on a practical level. Up to now the Chinese movies are rather bad.

Do you think your techniques or the way you think about film now, could help them in seeing their reality? At the stage of revolution in which they find themselves?

Not now, because they do not see any foreign pictures.

If talking about art is reactionary then we’ve got to talk about how we can achieve political ends without the medium of art. What I’m looking for is an alternative to guns. Obviously art is not the alternative.

Art is a special gun.

Would you lend us your camera to put a gun in it?

No. But there are different sorts of guns. There is a real gun and another sort of gun. One is science, one is art, one is a novel …

How do you explain the camera as a gun?

Well, ideas are guns. A lot of people are dying from ideas and dying for ideas. A gun is a practical idea. And an idea is a theoretical gun.

Would you come with us to Chicago this summer to shoot the demonstrations there? And let us use your camera both as idea and gun?

No. This is for Newsweek. The real picture to be done is a picture about the structure of all that. And this I’m not able to do because I’m not an American. I would be looking at it from an outside point of view. I could make a documentary. But I’m more of a novelist or a poet, and when I say “poet” I don’t mean any superiority. It’s just that a poet doesn’t work the same way as a newsreel man. I’m more of a chemist or a mathematician. And would you ask a mathematician to come to Chicago?

[Taped in San Francisco by Juris SVENDSEN, Tom LUDDY, and David MAIROWITZ. March 1968. Printed in San Francisco EXPRESS TIMES 14 March 1968, 8-9, as TALKING POLITICS WITH GODARD. ]

*****

4

Didn’t you do any work with the States-General?[8]

They had about fifty hours of footage. Nobody knows what is on it. Nobody knows where it is. Nobody knows who wants it. You have to pay them to see it, anyway, or else buy it, which is in pretty bad taste, I think.

But you’re still trying to work with film in factories and places like that, are you not? Don’t you think it could be useful?

Yes, in some degree, but I’d be really surprised if you could. Yes, I’d be really surprised. Well, I don’t know.

There’s been a lot of talk about the States-General in precisely those circles that have been interested in agit-film (Agitationskino), but then the directors’ group broke away, and then the Co-op.[9] The registered filmmakers’ union is all that’s left now. Still, a lot of people were talking about the States-General as if it were really important.

Yes. For two or three days a few thousand people got together who’d never met one another before … though afterwards they never saw each other again either. A few groups were formed and a few others gained strength. Some groups that arose in political meetings came out politicised in the process. And then there are always the organised communist filmmakers. They have done nothing at all.

How are the Action/Film Clubs (les Ciné-clubs d’action) involved?

[These groups, Film‘s editors say, “strive for a political counter-cinema; they were already active in the politicisation which took place at the time of the Algerian war. Filmmakers from these clubs (which include Communist Party members) agitate tirelessly with film.”]

Not at all. The Party filmmakers and cameramen did next to nothing. They never do. There are also some little peripheral groups, groups of workers who have been investigating the possibilities in film; they’re trying to create a counter-cinema on their own. There are the regular film-club people. And now there are the people who’ve gotten together to work on the ciné-tracts, who want to try to carry them further.

Are they students?

No. Only a few. Chris Marker is involved in this work, I am, too, and five or six other people. We are going to try to work more with the people from the People’s Workshops (les Ateliers populaires).[10] You know? The people who made the May posters. They are very well-organised and they’ve been quite successful. I think the ciné-tracts were really a good idea. They started out with things about the police, about the repression, in an attempt to publicise what had been happening. The newspapers had been suppressing a lot. To make it more widely known, they simply filmed photographs, for example. I mean, they made films, but very stylised. Marker made a few movies only from photos. I think it’s a good idea. I’ve been doing something similar for some time now in my movies. You take a photograph and a statement by someone like Lenin or Che, and then you divide Che’s sentence up into, let’s say ten parts, one word per image, and then you add the photo that corresponds to the meaning, “corresponds” either with it or goes against it, depending on the circumstances. That’s a ciné-tract. But there are lots of other ways. It’s still a pretty individual matter, still to a certain degree a work of art.

For whom do they make them? What kinds of audience?

They make them for everyone. They’re for anybody who wants them … the film-clubs, groups, the unions. Or you can show them in factories, wherever you have a contact. Or you can give them away. It doesn’t matter.

I’ve heard that some of the students’ groups were involved. Who organised their distribution?

The people who’d been involved with them. In connection with certain factories, certain groups É Besides, some of them knew each other already. Everybody should be making ciné-tracts. Some have been sent abroad, to London and to Italy.

Weren’t a couple of guys named Godard and Marker deeply involved in this work?

Yes. But only for practical reasons. Godard made a few, because he had a sixteen-millimeter camera. There were about forty. But now everybody’s back in his own corner again. But the point is to be making them all the time. There should be discussion and plans of action to vote on. There have been many screenings in Paris and elsewhere. The police came to a recent screening and confiscated everything. I wasn’t there. The ciné-tracts are made for agitation. We also make them to send abroad. But basically they’re for groups, to start discussions.

That’s the kind of work that was discussed in the States-General. Films ought to be made anonymously. But already the Co-op is busy now dealing in directors.

The Co-op is a real mess.

People are still making movies from scripts, but work with ciné-tracts is a much more political kind of work.

But it’s possible to be doing both. You can carry on cultural agitation and do political work at the same time. I’ve done something like that myself, with the Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung.[11] It ought to be just what the Marxist-Leninists who’ve been working with the Quotations from Chairman Mao have been waiting for.

The statutes of the States-General say that film has to be transformed into “a public service.” Has anything really been changed since last May?

No, not really. No. Now it’s worse. The only way to make films differently lies in doing it little by little. I think it is possible, it can be done É I don’t know. The structures are already there. You have your place within them. But if you’re in the process of changing yourself, if you refuse to make films the same way, then it’s possible. You’ve got to give it all up. You’ve got to change the life you’ve been living. Making a movie is very easy. It’s much harder to make changes. Almost nobody wants to. This was obvious at Avignon. Béjart [12] isn’t dancing any differently now than he used to. That’s all there is to it. That’s how it is. You have to make a complete change. And it’s hard.

You have to change the whole system, too. Everything in film …

You have to smash the system. You can’t just make movies now. You’ve got to … But nobody really wants to. They all want to hang on to their privileges, whatever they are. To make a movie right, they tell you, you’ve got to have a big camera, a big crew, and a cast of thousands. Lots of money. That’s how it is. That’s how you can do it, if you’re living in a socialist paradise. But you can’t do it here, now. Maybe our kids will, but we can’t. Take three photos; make a movie with that. Make movies differently. We can … Make your movie with a Mitchell (camera), if you can. If you can’t, it doesn’t matter. You stop making movies just to shoot film. You can make movies cheaply. Why do you always have to have synch-sound? It’s expensive. All you have to do is film the people when they’re listening, not when they’re talking. That way you shoot silent. You add the sound later. That’s how to make a sound movie cheaply … You know, you just can’t keep on making movies the same way …

[Extracts from text, in German, taped in Paris in August 1968, printed “as nearly verbatim as possible” in Film VII, 4 (April 1969) 22-26 as DIE KUNST IST EINE IDEE DER KAPITALISTEN. English text copyright 1970 by Jack Flash.]

*****

5

Personally, I think I have nothing to say. No, I don’t see what I can do. What kind of magazine? Can you afford to throw money away? The magazines now in existence are useless; the least they could do is merge.

But there is now no magazine that systematically studies the economic infrastructure of film.

Yes, but in the final analysis it’s all tied together. You can’t restrict it to film alone. It’s tied up with political activity … Two or three groups have been formed inside film. If you’re going to start a magazine, you should get together with them. Burch and Fieschi have a school[13] of their own now, but I don’t know whether they have the money for a magazine. Besides, they’re more academic, less politicised, lots say they’re more theoretical than some others. Losfeld[14] offered to pay for a magazine, but under any other circumstances I don’t see … Or else use mimeographed leaflets.

Despite this, there are some real differences.

Yes, there are. There are indeed. But in that case, what’s the point in having a magazine? When what you could do is make films?

Exactly. Maybe both at once …

A magazine is interesting if it takes clear theoretical stands … A magazine isn’t interesting – well, I don’t know … — unless you have to have it to get the movies you’re making into circulation. If you don’t make the movies, if all you do is make your magazine and not make any movies, the way it’s been up to now …

Okay. But you’ve got to get these films into circulation. A magazine can help you get them into circulation.

Perhaps. If you like. A news sheet, a leaflet that told you what people were doing, something like that, in which you can go for the news you need, that’s all. Just news. Maybe a few notes on theory, every now and then, if you have space. Everybody who could do it at (their) own expense should do it; then you add three or four more sheets if the group thinks it has any interest. Nothing else. Something very simple. But a magazine? It always … it’s the truth, capital T, every month, just like that.

For example, Un Film comes les autres (A Movie Like the Others, 1968) is something that somebody might want to talk about.

I don’t see any point in talking about it. There’s maybe some point in showing it, now and then …

Right, show it everywhere …

No. Of course not. I don’t mind if it’s shown now and then, but I definitely don’t want it shown everywhere. Zanuck wants to show movies everywhere. Me, I don’t. Zanuck or Stalin … — because the distribution of films ran the same way with them both.

This doesn’t have to mean theatres.

No. Right. I agree. I think there ought to be a lot more movies like that, and when there are …

Yes, but if you do show this kind of movie in the usual places it’s going to bring about some real changes, both inside film and outside it …

I agree, completely. But it’s better to spend a little money making movies and use your energy seeing how you can get them shown. But you aren’t going to get that done in theory. You do it in practice. Theory … Everybody agrees now that you’re going to have to make different movies in different ways …

You might try, though, to use a magazine to get people together, start a group, or even, groups …

Yes, the problem that the magazines present is real and basic, I think. That is just the kind of work that you do not use a magazine to do. Later on you might need to have one, but you don’t need one now. It’s just the opposite of what it’s always been. I mean, Peking … the revolution in China didn’t come about because some people – Mao, or somebody else, I don’t know – said, “All right, first what we’ll do is start Peking News Service. Then people will join us. And then we’ll make the revolution in China.” Just the opposite. They didn’t start Peking News Service till they’d taken power.

But to know how to make movies, you have to do some theoretical work. Couldn’t you use a magazine to support you in your efforts to do some work in theory?

No. As things stand, the people who are ready now to make new movies (des films nouveaux) … There aren’t what I’d call masses of them and even if there were, they wouldn’t have the money you’d need to make masses of movies. There’s just a few. So what you have to say to each other can be passed around by a very simple means; on a typewritten sheet of paper. The place to start is from very simple and very practical problems. And from the point of view of the practical problems, there is already a magazine called Practical film (Cinéma pratique)[15] that tells you everything you need to know about all the gadgets, all the tricks … Read Practical film and reflect on it with the theory of Marx. I admit it’s extremely reactionary, but you’d only be using it for what it could tell you about technique, in which respect it’s very good – even best: it goes into detail, it gives all the addresses, that kind of thing. If a kid wants to shoot some film, it’s not in the Cahiers or Positif that he’s going to learn … He has to buy Practical film to find out where to get it and how to do it.

But isn’t it true that a kind of militant film is already being made now, underground, with very little in the way of means, with the bare necessities?

Yes, it is, but I’m pretty sure, too, that it will be condemned for a long time still to live in a state of dependence precisely on what it condemns, or at least on what it is reacting against. For theoretical reasons, then, you’re going to have to stop talking about film, if you want to be able to talk about it in the future; you have to talk about something other than film. Film has to arise in social practice with ideas about film. People have to make social practice and discover the ideas about film implicit in it. It’s all tied together … And it’s different in different places. The kind of film you can make in France now isn’t the film you can make in Guinea or South America.

I guess the notion now of author film (film d’auteur) has lost all its point …

We’ll talk about it later. Not about author film but about responsible parties (délégués responsables) or something like it. The man who painted the picture of Mao Tse-tung had been placed in charge of the painting; he was responsible for choosing the colors, things like that. But that isn’t why they say he’s its author, say he’s the comrade (camarade) responsible for the painting. There’s plainly no sense in having forty people to hold a single brush. It’s the same way with film. But we’re still a long way away. We’ve fought so hard to get the guys who were exploiting us off our backs. They were talking about what (Georges) Wilson[16] had done, you know; the stagehands were saying, “When you put on a play we’re never given a voice in the proceedings.” Someone said, “That sounds reasonable. Why don’t you give the stagehands a voice in the proceedings?” That’s when he said, “He’s a stagehand; I’m a theatre director.” As a matter of fact, if you push it far enough, someone tells ’em, “You know, of course, that before you choose a play you have to read sixty or so,” and at that point they’re likely to say, “Oh, well, forget it; I’d rather be a stagehand.” We’re nowhere near the root of the problem yet …

But collective creation is still quite utopic for film, is it not? For practical reasons? As things now stand it’s impossible to think even about collective montage, however interesting it would be: you just can’t have ten people working on one editing-bench.

No, but it’s the man in charge who … Take a car. You don’t need forty people to drive it. You need one. Right? But it’s possible still to have several people involved in deciding where it will take them all. It’s the same way with film. In practical terms, you can make movies with very few people; it is technically possible. And if there are only three or four of you there, it is much easier to talk it over than it would be if you were fifty or sixty. But it’s possible, too, to have projects for the fifty or sixty to vote on, and then choose the three or four who will actually make it. This is the problem that a committee faces: you choose one guy or another to do one thing or another; but it’s the committee that is making the movie. But as soon as you get to this point, you’ll have to be making radically different movies – much simpler movies; you’ll have to look at the problems from the other side, if you want to get back to simplicity and not simply be doing cheap what others are doing much more expensively.

Will there be a place for professional actors in this kind of film?

Yes, of course. You’d make the actor responsible for the action. The people who know what you have to do to bring in the fiction participate in it, too. They create. But the way they are used as a rule, they’re more like objects, things, something like that – at best, magic objects.

But if you use actors as subject, doesn’t that mean you use the public as object?

You can’t ask a theoretical question like that without saying, too, in the same breath that in practical terms it’s not a question at all. When you have to use an actor, you take an actor and you try (with his help) to see whether you can in fact use him.

One question you can ask, though, is whether acting, in the degree it is a profession, isn’t linked to a class-based oppression?

Yes, of course, but … Let’s be doing the things that don’t move us to ask such questions as that. All those guys in the actors’ union who sit around all afternoon talking at each other like that … They aren’t real problems.

Do you think the same way when it comes to writing a script … telling a story?

No, not at all. You are always telling stories. If you’re going to call a well-written book a “script”, all right. Some people have to take lots of notes, put them together in some fairly traditional-looking form; that’s their business.

In Un Film comme les autres the starting-point was the discussion those people were having … and the photos were added later?

Yes, that’s right.

So this is, at the same time, a very conscious aesthetic stand that you’re taking. Does it vary with the subject matter, the subject you have at hand, the subject that interests you?

The only idea in doing it like that was to get it done more simply and rapidly, in other words, to get it done more cheaply, and also more in movement in terms of the relations between its various parts; I mean by this that the shot that comes next comes out of the shot that it follows. In Un Film comme les autres some students are having a discussion; this has an interest in itself, you know, and it’s much better anyway trying to tell the story of May (1968) just as they tell it and not sticking a lot of other stuff in, and then sticking more talk on top of that, too. The way it is now, it holds together; several parts in the whole experience do come together; and it’s even possible to draw a few conclusions from it all when it’s over.

From this point of view, then, of showing the film, do you expect the spectator to take a part in it, too, and is his experience of the film something that takes it farther along, or do you think it’s simply something that comes along in addition, just like that, but nothing really?

It’s fine if there are discussions afterward, because there haven’t been any, in the past.

If it were in your power to do so, would you prevent the showing of your earlier films?

No. I don’t care. They have to be examined again, critically. You cannot deny what you’ve already done. Mine or others …

Nevertheless, you’ve broken with them, haven’t you?

Broken? No, changed.

Broken with their aesthetic, with their … call it “romanticism”?

Maybe not. Not that much. “Romanticism”? Misdirected, maybe. I haven’t been able to do any theorising. I’m trying to, that and practical work, too. I do a little of both. Right now, I’m doing nothing. But, I think, they’re equally hard.

Are you still making ciné-tracts?

Not right now, no. Maybe I’ll make some more, I don’t know …

What position do you take in regard to the purely formal work that is being done in film right now? In relation to somebody like (Jean-Daniel) Pollet[17] (maker of Méditerranée, 1963), for example?

That it’s interesting. If the States-General had the money still to make movies, movies like these would get made, too, but they just wouldn’t get as many votes as the others … These are theoretical movies É I think it would have been better for Pollet, though, to have done political work for three months before he started on Méditerranée; he’d have made a different movie. Méditerranée would have said something besides what it does about death. Maybe it would have had something to say about class struggle. It wouldn’t have talked about death and the Mediterranean basin as if it were Camus.

But we (Cinéthique) are going to talk about Pollet and his movie because he’s a member of the bourgeoisie, which involves him in problems – as it does you, too, doesn’t it?

It’s the problem the hippies are having, musicians, people like that, who could have radicalised but who don’t, stay outside it all, revert to the wild state, don’t want to be bourgeois and choose to revert to some state of nature or other, who don’t want to be anything else.

Yes, but at least Pollet is honest when he says, “I’m a bourgeois; I was born in a prison: bourgeois culture …”

But that’s easy to say. Leave Paris behind. Try to find work at Mazda [a battery manufacturer].[18] Then you can …

For example, he really wanted to find a way to work political meanings into (his movie Tu imagines) Robinson (1968), but he couldn’t.

That proves it’s just not enough. He’s not going to be able to find social practice all by himself, it is obvious. Correct ideas do not drop from the skies. He wants correct ideas to drop from the skies. So he’s saying, “If a correct idea drops on my head, I’ll pick up on it. But as long as it doesn’t, I can do nothing. I’d like to, but here I am, watching the sky, and nothing’s coming …”

He has political ideas, but he can’t work them out in film as yet.

(Cf. Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung, Peking Foreign Languages Press 1966, p. 206: “Where do correct ideas come from? Do they drop from the skies? No. Are they innate in the mind? No. They come from social practice, and from it alone; they come from three kinds of social practice, the struggle for production, the class struggle, and scientific experiment.” Where Do Correct Ideas Come From? (May 1963), first pocket edition, p. 1.)

That’s the hardest part of it all, right there. Because it is spectacle that you’re talking about when you’re talking about film, because it is spectacle, and because film is more bourgeois than any other kind of spectacle. The people who are working in spectacle, too, are real slaves. They’ve been “integrated” like the blacks in America. The stagehand at the T.N.P. (Théâtre National Populaire, “People’s National Theatre”) or the Comédie-Française is an Uncle Tom, in relation to the spectacle he’s helping to make. He has nothing to do with the working-class, really; he is a worker, he gets paid what a worker at Renault is likely to get; but there’s just no connection … he has no real experience of the working-class struggle. What he calls working-class struggle takes place deep inside it, anyway; all it is, as a matter of fact is tolerance or privilege (in one degree or another) somewhere deep inside the big bourgeois game. There is no class struggle in the way the stagehands and Robert Hirsch (director of the Comédie-Française)[19] relate to each other at work. For the people who work in spectacle, the only way to radicalise is to cut all ties, all … I don’t mean they have to forget what they’ve learned that has any value as theory, but they should put it aside, keep it in reserve and keep checking it over as they go along, if they want to get off to a new start. This means they have to turn their backs on É leave it all behind, what they usually do. Right now, it doesn’t look like you’ve much of a chance to come out a winner. The bourgeois ideology of spectacle has reached a still point … And it’s got such strength it’s everywhere now, even in the most oppressed countries of the Third Word. But, you know, it’s harder for a man like Pollet to make the movie he’d like to make than it is for … It’s easier for Ousmane (Sembène, Senegalese, maker of The Black Girl (1966) and The Money Order (1968))[20] to find out … to know what he has to do than it is for Pollet. Ousmane doesn’t have to go around saying, “I’d really like to but I just can’t get it together.” No, he says, “I’d really like to, but they’ve been keeping me from it.”

What do you mean when you say you have to leave it all behind?

There are two different things you can do. There are several theatre troupes now that perform in the streets, do it quite differently … They go out of the suburban slums, things like that, to reach people better, they do things to get closer to people. It’s the same way with film. It’s very simple, really. You say you’re politicised now. All right. There are groups that exist. They’re easy to join. You can take part in the discussions, you can listen, and look; you can be very serious about your listening and looking. The movies you’ll make then will just have to be different. I’m not saying it’s easy or even that it’s simple at all. I’m saying that it seems to me the only thing you can do. You know, I more or less agree with the situationists; they say that it’s all finally integrated; it gets integrated in spectacle; it’s all spectacle.

But there’s no point in such clowning if you don’t think movies have some use in social practice today.

But I’m sure they’ve a use. – But what I’m calling “film”, you’ve maybe noticed, it’s everything, it’s image and sound, in any medium: in newspapers, books, showings on television sets or screens, in theatres or in meeting-rooms … It has to be useful, it’s like … it is literature, it is speech, it is science …

Yes, but if you don’t pay close attention to its political meanings, if you don’t keep an eye on its impact, the effect it is having …

All right. Let’s pay attention. If it’s movies you’re making, you’re saying that when you make them you’re paying attention to … Well, in any case, it’s evolving, it is changing, it isn’t going to be good unto all eternity.

But one of the jobs that still needs to be done (now it’s urgent) lies in seeing that the public can get to see what’s being made. This means you’ll have to deal with circuits of distribution.

No it doesn’t. Why do you have to have circuits of distribution? As things stand, circuits of distribution, they put you … It’s Amalgamated Drygoods (c’est Prisunic), it is Ford (car manufacturer) that talks about circuits of distribution. Let’s say simply that people have to see the movies. But even more than that, they have to make them. You’ll have to start making a simpler product. You’ll have to make it more cheaply. You’ll have to make something that can keep you going behind enemy lines. It will have to be financed by collections, contributions from organisations that choose to involve themselves. Super-Eight is still too expensive, and you have to have a really good projector. You’ll have to have one or two other guys to make your movies, so while one is shooting, the other guy can run around France showing the film. In practical terms, what you’ll have is an underground network, a lot of different maquis, that keep in touch. You could say that their aim is to produce … I mean, to make acts of resistance. Sabotage means you make movies, in Super 8 or on video-tape, it all depends on what each maquis has at its disposal. How much does a two-and-a-half minute reel of sixteen(millimeter) cost, in black-and -white, silent? Five thousand old francs. The same thing in eight (millimeter)? Two thousand francs. A thirty-minute movie costs ten times two thousand francs. If ten different people each contribute two thousand francs, you can make a thirty-minute movie each month. There are a lot of people around who can afford to contribute two thousand francs. Then, let’s see: why should you make it, that movie? There aren’t so many problems. And if you somehow run into more money, if you can make bigger movies than that, you have to ask whether you really need them.

That sounds a little like what was happening last May.

The criticism that I have to make of what happened last May is, simply, that much too much footage was shot. They’d been deprived in the past, so they wasted a lot, just shooting it up; it’s even hard to do anything with what they did shoot. What little’s been done is all right, but you certainly didn’t need that much footage to get it done. Now there’s no money to do anything else. You know, nothing prevents a man like Pollet, as a matter of fact, he or others, from doing something, through the States-General or something else, with what’s around, but he doesn’t want to; he sits around saying, “Oh, I’m a member of the bourgeoisie, so I’m never going to get out.” It has to be said; the people making experimental film (du cinéma de recherché), but who are still “oppressed” because they never succeed in doing what they really want to do, they’re oppressed within themselves, I agree, but they are nevertheless much less oppressed, really, than any worker or any member of an oppressed class that is oppressed by the whole system. He can find shelter in music, in art, in his experiments, which the other guy can’t: he’s never been to school. You see what I mean: the other guy is oppressed every minute of his life, while guys like (Marcel) Hanoun (a French filmmaker)[21] and Pollet – or like me – who stand around saying, “Okay, I’ll do it alone” … It’s a fact; we’re never too much in touch; we’re never in contact enough. I think we have to improve our contacts. I know it’s not easy. The day when there are as many manual laborers who take an interest in art as there are intellectual workers, the final link will have been made. I think Pollet, Hanoun, anyone, really, should make their movies, but in the closest touch possible, rather than each outside it all. And I don’t mean that they keep in touch by reading a magazine to see what’s going on; I don’t want them to say, “Oh, I keep up on my reading; I am aware what’s going on,” or even, “I’m a poet, so I feel it all coming down,” not putting it quite like that, I guess, but still an anarchist, in the bad sense; I mean, in the sense it has for the bourgeoisie; I mean, “outside”. The real meaning of the word “anarchy” lies in things like workers’ councils, communes, land redistribution, sharing the work. The work gets done little by little. There is never a big, real break É

[Extracts from text, in French (which seems taped), published, undated by J-P. C. (?) and Gerard LEBLANC in Cinéthique #1 (janvier 1969) 3-12 as UN CINEASTE COMME LES AUTRES. English text copyright 1970 by Jack Flash.]

*****

6

I’d like to ask you, first, to tell us what a director is. Can you say he is someone who has a profession, which is called film, or is it something more than that?

I think we’ve gotten off to a bad start, with questions like that. I thought this was called Initiation in Film. Initiation … In the first place, it has a religious sound to it that … I don’t like that, and É Because the second question you ask is already understood in it. You are already deep in a grammar, an ideology, which is religious, or political, and which, in the long run … there are, you know, there are …

And you attach … you have always attached great importance to film. For you it is extremely important.

Yes, at one time. At one time, yes, because … I mean, it was necessary, at one time … Let’s say, it was the only way I could do it. It was saying, I exist. But in fact it was only an attempt … it was reformist, if you like. And now, I think, after … I mean, for me, after what happened last May, you know, it opened my eyes. And as a director, a man is É if he agrees to be that and that only, he is only a cultural product, willed a cultural product by the state, tolerated by the ideology of imperialism, it has to be said: there are different forms of imperialism, and that is one of them, too; it is cultural imperialism. And, you know, a program like the one you have here, if it was really É if it was a real Initiation in Film, it really was what it says it is, it wouldn’t be shown on television. It would show what a film is. The first thing it would do would be to say … Because no one has a very clear idea of what a film is, you know, and because the ideas people have about what a film is have all been provided by Hollywood, by the Americans, because it was they who invented the image. And I, I go even further: I think every image, I mean everything people call “image”, nobody has a very clear idea of what it is, and because now with all this development the image has been undergoing, and television and publishing, too, that kind of thing, people are … The image … I mean, Gutenberg, what he invented[22] … not Gutenberg, really, but his equivalent for the image, something like that, it hasn’t really changed since Gutenberg. The image is still pious, I mean it’s being manufactured by men who are, in one degree or another pious men; they can even be rebels … sometimes they do; but they don’t really know …

And you, you began … one could say, with a certain conception of film …

Yes, at the time they were ////////////// us. Yes. We wanted to make images, so someone said … Okay. Anyway, people are always talking about the images, as a matter of fact, and never about the sounds, or so it seems. The sound is always defined as an image in sound (une image sonore) …

In other words, a director, when you started, for you … Was it a pleasure, or did you do it because you were forced to?

I think it’s a drug. It is a drug, and today, still, three out of every four people who love film, who are trying to fight the kind of film they call “commercial” are, let’s say they’re on drugs, the way the beatniks fight the establishment. Fine. This is the first step in a man’s act of revolt, but you have to go beyond it, and then you’ve got to go beyond it again. And what is truly film, you know, after … I mean, here in France, there are people … just a few … people who have been trying to carry on the struggle, who regrouped shortly after last May, and whose films or attempts at films are É are completely É have been banned, you know. These people are trying to make films, to show films to the high-school kids (les lycéens), and in point of fact the only place where the films from last May (which, God knows, were not very good nor even really very instructive, nothing like that, but they were interesting, if only because they came from some place besides Pathé News or Hollywood or French T.V.), the only place where the police come to stop their being shown is in point of fact to the high-school kids – or, in other words, the people who supposedly are learning knowledge, you know.

Do you mean that film has to stop being the work of specialists?

No, no. Not at all! It was … it was never … it was invented by a guy whose name is Lumi?re, who was anything but a specialist, who was making all kinds of things, and then he made that, too. Later on it fell into the hands of the specialists. All kinds of specialists. The specialists in finance, the specialists in culture, things like that.

Oh. All right. But, you know, for the public, the director … He’s always a specialist. I mean …

It would be better, it would be better to tell the public that directors don’t exist, there are no directors, and that every movie you see … Yes, there is in fact a director, a very big man, who is de Gaulle. Who isn’t … he didn’t make them himself, but the line they follow, every text, every sentence in ’em is produced … is a product of Gaullism. This is what I mean when I say it’s de Gaulle (or his lackeys) who directs them. I mean … Then, too, just the opposite: the French people have never made a film. The French people have never made a single film. None whatsoever. You can’t. Take anyone coming out of the theatre, anybody at all, and ask him, “Have you ever in all your life seen a film that talks about you, the life you have with your wife, with your kids, about the money you take home, about your … I mean, everything. Or, at the very least, a part of something or other, it doesn’t matter.” Never. He goes to see other people’s movies. Then, too, he’s learned his lesson so well he’s completely unaware of it all. He’s really nice: he even pays to see them.

But, don’t you think, isn’t it possible, with the system as it now exists, for filmmakers – like yourself, for example – to make this kind of movie?

But in the first place it would mean that you had to negate yourself as a filmmaker, as you have been tolerated, and that, I mean … A pact exists, between what people call the revisionists or the imperialists, for example, from that point of view. For me, it’s the same thing. Okay. But there is no such thing in France as a communist film. Although the French Communist Party … Today still, now more than ever before, shows it’s the only real party in France. The odd thing is, that there is no such thing as a communist party in É no such thing as a communist film in France. There never has been. Though, if you try to tell them that, they always say, “Oh, yes, there has been. In 1936, there was a film in ’36 … “[23]

Renoir’s …

Renoir was anything but a communist. He’s some kind of anarchist fucker who was nice enough and just big enough, too, to make that movie, because he was more or less in synch with his times. And now just look where he is, and look at the kind of movies he’s making. That’s it right there. So, it … it is meaningless, because, you know, nobody at the Political Bureau in Paris is ever going to have the guts it would take to go see … I can give you a good example. There is Rhodiacéta, in Besançon.[24] There are some people there who are interested in film. Okay. People have been lending them cameras, giving them film, stuff like that, because of the connections and the friendship we’ve had for them, and now they’ve shot their first film, all by themselves, with … cutting corners, but they, they …

You mean the workers?

Yes, the workers. And they appealed to the Party for aid, so they could finish their movie, and the Party refused. They appealed to the C. G. T.,[25] too, which also refused. So it’s been us, the so-called “leftists”, who have had to furnish the film they need to finish their movie. So it’s obvious that it’s all pretty complicated. That’s just one example, but it’s a very precise one. I mean … But as for film in general … So, you have to negate yourself in the degree that you are É See, you’ve come to interview me. Why? Because, because I’ve … you’ve seen my name in the papers so many times … Oh, yes. So, because you’ve seen it so often … Oh, yes.

But we’ve seen your movies, too …

Sure you did, but that’s not interesting, it’s not interesting. What would make an interesting interview, would be asking someone, and working with someone … someone you found in the street, anybody at all, or if you know other people like that [!] … and take this guy and ask him, “What does it mean, to direct … a film?” Okay. Then, you’d start to talk it over together. If he hasn’t the faintest idea, well, all right: you start to work on it, to see what it could be, and then, in two or three years or maybe in fifteen years, you come up with a totally, a totally different definition.

You mean, you think that direction has to be taken out of the hands of directors, and, in the end, that …

No. I think film has to be made … maybe by filmmakers still, for the meanwhile, but with people who have never made any film, so that later, maybe – whether these people here realise they’re really not qualified to make movies, because they’ve found through the people (I’m not exaggerating) a real idea … While, as for us, we, we’re still relying, we still rely on a lot of reflexes, that are not even ours, really. We say we’re trying to fight them, but we’re not even aware … Just in the words that we speak, in the way that we frame … way we make the images. It’s even worse with television. Besides, even the most sympathetic … All you really have to have is a camera, that’s all. But there are twenty of you to do the job. Why? It would be better … you’d be better off making other movies, because two is enough to … you can do it with two, the job you’re doing.

You think you can give people cameras … give everybody a camera, and let them express themselves?

That means nothing, “give them cameras”. What you mean is … “Express themselves?” It’s Edgar Faure[26] who’s always saying … it’s André Malraux[27] who says, “There’s got to be freedom of expression!” Which means nothing. And, even then, it’s only some kinds they can tolerate. It’s not all. – But that is meaningless, too.

So, what’s the solution?

Okay. The solution is to stop making … making movies for … for … for imperialism. It means that, if you work for the O. R. T. F. (Office de la Radio-télévision française), you stop making movies for the O. R. T. F., or if you do keep making movies, you make movies they won’t be able to show now. When there are lots of movies like that, that they can’t show, then they’ll begin to see that it just isn’t as easy as all that. That kind of thing. It means that you stop every time, it’s something you have to do every day, like that. You’re going to tell me it’s easy for me to talk like that, but I … it’s what I’ve always been doing, right from the start, even in a bad sense. It means … it means refusing … Because you’re relying … Or even myself: the speech I’m making you now is the kind of speech professors make. I don’t care to be a professor. I don’t care to be a teacher or a student. I want to be both, at the same time. Of course, there is a time … There is someone who knows more who ought to speak, but not … not because he’s had his name in the papers, not because he’s had more experience – or, if he has had more experience, it has not to be the kind of experience everyone else has been having. No director … the only directors who have had even a little experience in the kind of film that has to be made, were a few of the Russian directors, right after the Revolution É men like Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov, who were soon, uh, stopped, you know, and put back on the … on a … on the straight and narrow path.

You’ve always said that, for you, film was something like a way of life. Or that it was tied …

[THE TAPE RUNS OUT OF THE MACHINE. A NEW REEL. THE CLAP SAYS, “CINEMA SIX, two, take one.”]

Do you think there’s a way out, for you filmmakers?

Yes, in practical terms there are things you can do … on the one hand, outside the fascist workshops; on the other … I mean, everybody will take it on himself to do what he has to do; and, on the other, if you stay inside it, change it little by little, which isn’t easy. In the army … I mean, to make a protest within the army isn’t as easy as it is in some little outfit or on É on a stage. Look, right now, you’re doing just what I think you have not to do. I mean, you rely on forms of speech, but what you’re saying is that you look at them critically. So you keep talking, but it just isn’t interesting. The only thing that just might be interesting … be interesting and at the same time a real protest, would be to use the raw stock you’ve got, because it’s already paid for, use it but just to light-strike it, or, if you did shoot it, shoot it so it couldn’t be shown. If that’s all you did, you’d have made it impossible for the … you’d have made it impossible for them to … For example, not … simply not …

That’s incredible, I don’t believe you, expose it like that, light-strike it, doing something like that … What? Waste film? Waste film that belongs to the 0. R. T. F.? Because it’s my footage and I’m just throwing it away if I do that … Waste it? In … — So, from time to time you waste as much stuff as you can, indiscriminately … At that moment, I think, the protest …

That’s not the reason. But it’d show them … — And I don’t mean you do it once and once only. I mean that you have to do it over and over again … — All the time. For example, this is a … quite practical, really. Right now, you’re doing precisely … There are five people here listening to me as if I were giving a lecture. Well, I’ve … I’ve nothing, really, to teach them. So I don’t see why it’s not him or you or that guy over there who É who’s telling people what he says on French television … I mean, what he thinks. They’re the ones who … But I’m right, yes, I am … Why? You can see it clearly in the famous face-to-face interviews, in things like that. The C. G. T. cameraman É For example, last May, the C. G. T. cameraman did nothing to sabotage de Gaulle; he filmed him as well as he could, even though he was on strike against him. But he was doing his … he was doing his job, is what they call it, his little job, what is …

But, as soon as the revolution …

That’s … that’s what I meant … No. No. But at that level, on his level … — Yes … — the action he took to back up his demands, that’s what it was, the action he took to back up his demands. But that … he didn’t do it. He tries. The power structure is well aware of it, much more aware of it than he thinks, but that’s the only way. You have to fight with weapons É with the weapons you have.

So you sabotage.

But … Sabotage? No. You … On the contrary. You let … Stealing more and more film from the O. R. T. F. … — Every militant movie is made with film stolen from the O. R. T. F. That’s good, right there, but there’s a lot of other things that go like that. On the level of the text and É on the level of text and of meaning, everything that is being made today, eighty percent, at least, is – and even if it is “protest” film – is half-fascist in the way it works because it follows rules of grammar and discourse just like the papers, or books.

What do you have to do to change these rules?

Well, in the first place, you have to reflect, you have to reflect and you have to do something different and do it with different people, people who haven’t already learned these rules. You’ve got to go see the illiterates and the pariahs. I don’t mean, uh … Yes, I do, the pariahs, in both senses of the word. – The people who’ve been deprived of film. A guy who’s … One of the people who’ve made de Funès big box-office.[28] The proof he’s been deprived is, he goes to see de Funès.

But, let’s say, as soon as we’ve made the revolution, what kind of film …

You don’t make the revolution just like that. It takes tens and hundreds of years. The only place they really stopped making movies, at the same time they closed the universities, is in China, for example. It really impressed me because nowhere else … Look in France, last May, everyone was on strike. Everyone. Even the Mogador.[29] Even the Rheims soccer team. Everything. Everything. There was one single place that didn’t close, films kept on being shown, in the theatres, whether the projectionists belonged to the C. G. T. or they didn’t. They got their pay raise so they kept on projecting. You see? In other words, the projection of images just had to go on. Even the papers stopped printing. But the projection of movies? It never stopped. And even … For example, at Avignon and Venice, even the protestors … The one thing they didn’t protest was the projection of movies. In China they stopped. Why? Because they realised that the movies … In the wake of their disagreements with the Russians, they realised that the movies they’d been making were modelled on the Russians’ movies. The Russians’ movies were modelled on the American movies. So they simply said to themselves, “That won’t do. We’ll shoot some film from time to time. We’ll film the first of May, or the atomic bomb, or chairman Mao, what’s so important it has to be shown? We’ll shoot it any old way, in other words like Lumière, in other words, it’s pretty good and then uh, we’ll think about it all later on, because the problem of the image, you know, nobody is really in a position just now to solve them (sic), because nobody has really, uh … There are more important jobs that have to get done – the cultural revolution, lots of other problems that have to be solved. And the problem of the image is so complex, since for the last two thousand years of civilisation we’re still in the same … still in the ideology of the image: the image is very important but it is only an ideology; so let’s just stop.”

But don’t you think … I mean, you seem very close to Lumière … Take Lumière, for example … [IT BECOMES DIFFICULT, IF NOT IMPOSSIBLE, TO TELL WHAT ANYONE IS SAYING: J-L. G. AND HIS INTERLOCUTOR TRY TO SHOUT EACH OTHER DOWN: BUT THE QUESTIONER CLEARLY ENDS HIS SPEECH:] … Lumière?

No, no. Not necessarily. But at least let’s say it’s not that remote. The beginnings of paintings? Nobody knows. Lumière? You’ve got a date. Fifty years ago. In two hundred years, it’ll have been lost, already. No one will know, no one will know where the movies are. You see. We can look at it again. We can date it, we can still follow the development. So let’s study Russian revolutionary film, which hasn’t been studied yet, really. It hasn’t. Not by the Russians or the Americans or anyone, really. What has been done is purely anecdotal. They’ll tell you, Eisenstein made this movie that year and that movie then. But what were his ties at the time? Nobody ever says anything about that. They don’t even know whether he sided with Trotsky or Bukharin or Stalin or Lenin or who. Nobody knows a thing about it. So É But he was up to his neck in it. He talked politics all day long with his comrades, and all that. And that’s where he É it was to get out of these discussions that he made É that he made his movies.

They are …

So, let’s stop – no, the … I mean, I think … There are a lot of things you could do; they go from, it goes from dynamiting some specific movie theatres, occasional terrorist tactics, sabotage, and the opposite; the reconstruction of certain movies which is important, too. Let’s make movies that … let’s be … that the O. R. T. F. won’t be able to show, or that they will but only after a struggle, because it will be a struggle …

This means that you do still have to make movies.

You have to make movies, but stop making them the way they are being made. They’ll tell you (that) you have to have three men to handle the camera. Try to have one or else eighty. Let’s say you’ve got a Coutant (camera). When they tell you have to have three men – right here you have three or four men, right? – but they’ve done all right with just one, haven’t they? One is enough. Okay. So, you tell them, either I have to be by myself, or else I’ll have to have a hundred and fifty man crew, because if you did, you’d be having new problems. Then you’ll find the … you’ll find … you’ll find the true … you’ll find the new ways.

But it’s not enough simply to change the kind of crew you have to be able to make different movies.

Of course not. It’s not enough. I’m just giving one … I’m telling you one of a thousand things you could do. It’s not up to me. It’s your … it’s you who’s got to do it.

But in relation to the content of these movies, or in relation to their form, if you prefer …

It’s the same thing …

How are they to be different?

It’s the same thing … But … Different? I don’t know. Something that’s big, make it little. Something’s that little, make it big. Do that, systematically. Then, too, go to the people who don’t make filmÑnot to the ones who want to make film, but who haven’t … the ones who aren’t making their images, who aren’t making images. The images and sounds they see, somebody tells them, “That’s you, there,” it isn’t, it’s not them, it isn’t true. So go to them, listen to them talking. Someone from the South doesn’t talk like somebody from the North. Things like that. Go ask the guy, “If you had to film your wife now, how’d you do it?”

But it’s not enough just to go out with a camera … You’ve got to get them to participate.

It doesn’t matter. On the contrary. Let … Stop the cameras. For a while take still-photos. Show still-photos on television. Bring a photo of me back to your boss. That’s it right there.

No, it’s only that, you know, the route you think film should take to … I mean, without going into any of the details, being less … let’s say, being less suicidal, and, I don’t know … Because I get the impression, uh, from what you’ve been saying … it’s pretty frightening, I think …

[AT THE SAME TIME:] I … In the degree in which you’ve said that … No. No. Not at all. Me? My ideas … Ideas for films? I’ve got ’em …

Film was your life. How can you stop making film?

But I’m not.

Okay. Then can you tell us why you continue …

[PAUSE. A SECOND INTERLOCUTOR UNDERTAKES A NEW LINE OF QUESTIONING.]

You keep referring to Lumière, going back to Lumière …

Not any more. I said so … It’s quite practical still for some people, more for … more than others. I went back to that stuff ten years ago. But if it helps people, going back to Lumière …

[J. -L. G.’s FIRST INTERLOCUTOR RETURNS TO HIS OLD LINE OF QUESTIONING:]

No, not just like that … No. What can … What you’re saying … Why do you continue, then if you do it in spite of yourself? Because I … What bothers me, a little, is that I get the feeling it’s a real dead-end. So, don’t you think it’d still be good for you to try and see how to get out?

[THE TAPE RUNS OUT OF THE MACHINE. NEW REEL. THE CLAP SAYS “CINEMA SIX, three, take one.” — “Hold on” — “We’re not shooting?” — “Don’t shoot.” — J. -L. G. : “Now it’s ‘two’.” — “Yes.” — “Yes, go on.” — “SECOND SET-UP, CINEMA SIX, three, take one.”]

You’ve often said that film and life were one and the same thing for you. So, do you think that if you stop making movies …

You mean I lived and made film while others were dying little by little. You ran into them in the street, they continue to live but in effect they were dead.

But you continue to live, so you continue to make movies.

Um?

You want to continue to live, so you continue to make movies.

Not necess(arily) … But I don’t know what you’re talking about. “Film?” I never did know and now less than ever. I think other people are capable of finding it out, but I … I certainly can’t, with a … that kind of thing – but I’d really like to know what it is, of course.

But, I found you in a place that ought to be very familiar to you …

Yes, it’s a cutting-room. It’s a cutting-room that several of us have gotten together to rent, that we share. But, I think … You know, I don’t make that much use of it, because I’m trying to make movies that don’t require editing (des films sans montage), you know, movies that are much simpler, by … by doing the shooting exclusively in terms of … Kodak makes pretty good reels: there are two-minute reels, five-minute reels, ten- minute reels. That’s good enough. That’s all I need. And then I … The work consists in shooting by reels and not in making what they call “montage”, which has been completely … What they are calling “montage” now has nothing … is nothing compared to what the Russians were trying to … to find when they called it “montage”.

I mean, film …