In the early 1950s Hollywood explored several new technologies in order to fight a major box office decline. In 1948, more than 90 million Americans had visited the theatre at least once a week, but this figure decreased to 51 million in 1952. [1] In 1953, only 32.4 per cent of all cinemas were making profit from the sale of tickets. [2] Twentieth-Century Fox, the studio of president Spyros S. Skouras and executive in charge of production Darryl F. Zanuck, did not escape the crisis. While Skouras had announced record profits in May 1946, the studio’s revenues were falling rapidly by the end of 1948. [3] In 1952, Fox’s incomes from admissions reached the lowest point since 1943. [4]

The different tendencies that caused this economic decline have been extensively commented upon. The Paramount Consent Decree of May 1948 had demanded the studios to divest themselves of their theatre holdings, while the prohibition against block booking kept them from imposing units of multiple inferior pictures on exhibitors. [5] To make matters worse, the investigations of the House Committee on Un-American Activities had prompted successful boycott campaigns against films made by alleged left-wingers. [6] More importantly, Hollywood was failing to respond to the needs of a heavily changed and diversified audience. Postwar baby boomers had moved to the suburbs, far from the downtown first-run movie theatres. [7] There they were developing new leisure-time activities, outside (outdoor sports, barbecues and recreation parks), but especially inside the house, as the television became a popular alternative to the big screen. Although Tino Balio has argued that “TV did not make significant inroads into moviegoing until the mid-fifties”, it is often identified as the main reason for Hollywood’s economic crisis: the more Americans acquired television receivers, the less they attended film theaters. [8]

In response to these developments, the film industry needed to strengthen the appeal of its product. After experiments with three-colour Technicolor, stereophonic sound and 3-D, the success of the three-strip widescreen process Cinerama in 1952 finally convinced Hollywood that widescreen could lure back moviegoers. Four studios of the Big Five (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Warner Bros., Paramount Pictures and Twentieth-Century Fox) looked into the possibility of creating their own widescreen system. Eventually, Fox obtained the formula for the anamorphic Hypergonar lens, developed by French astronomer Henri Chrétien, only one day before he was contacted by Warner’s representatives. [9] In February 1953, the studio started filming its first CinemaScope pictures.

The anamorphic technology which CinemaScope was based on had a clear impact on how films were made and on how they looked. While Fox filmed its first Scope pictures – How to Marry a Millionaire (Jean Negulesco, 1953), The Robe (Henry Koster, 1953) and Beneath the 12-Mile Reef (Robert D. Webb, 1953) – with the original Chrétien lenses, manufacturer Bausch & Lomb would provide several revised designs throughout the 1950s. Despite various updates to the Hypergonar, they did, however, never manage to eliminate all of the technical flaws. [10] The CinemaScope process relied on lens attachments that squeezed a wide-angle view onto 35mm film. During projection, the reversed mechanism unsqueezed the image, resulting in an aspect ratio of 2.66:1. This would be reduced to 2.55 because of engineering considerations, and to 2.35 after the addition of an optical soundtrack. The compression factor was roughly 2:1, but tended to vary across the surface of the lens. This made figures or objects near the edges of the image appear thinner than those positioned centrally. Even more remarkable, actors shot in close-up suffered from CinemaScope mumps, their faces stretched out horizontally. Actors and objects appeared at their sharpest when filmed from far back, so directors were advised to put the camera no closer than six or seven feet. [11]

The first generations of CinemaScope lenses consisted of a prime lens and an anamorphic attachment which had to be focused separately. Filmmakers therefore had to avoid complex camera or character movements so that the focus did not have to be adapted during the shot. In addition, the anamorphic lens design, even after both lenses were joined in one unit, drastically reduced the light-gathering power. This had the most noticeable impact in the domain of staging: as the CinemaScope lenses provided very little depth of field, directors were forced to spread out the action over the lateral, rather than the recessive axis. A typical early CinemaScope composition contained several characters on one plane, relatively far from the camera, in a static layout. These changes made cutting less necessary, as such a composition often included all the essential elements of a scene. Moreover, quick cuts between long shots in widescreen were said to confuse rather than engage spectators. [12]

The technical restrictions of the anamorphic technology had significant aesthetic consequences. In general, CinemaScope films had shots that lasted longer, the camera was put further back, compositions got more static, depth staging became rarer, and more characters were used in order to fill the frame. Despite the efforts Fox made in order to minimise reports on the extensive influence of CinemaScope on film style and production, its artistic personnel approached the transition with mixed feelings. Nonetheless, various critics, most notably those writing for Cahiers du cinéma in France and Movie in Britain, were famously enthusiastic about the stylistic choices the anamorphic widescreen system seemed to encourage. Their ideas still mark the discourse on CinemaScope style today.

This article explores film style in 1950s CinemaScope. It focuses on the two stylistic elements that were most frequently commented upon by trade papers and critics: the length of the takes and the scale of the shots. Adopting a data-driven methodology, the article will analyze the quantifiable formal parameters average shot length (ASL) and shot scale in a stratified sample of 31 CinemaScope films released in the 1950s. In order to find explanations for the trends revealed by this dataset, it will take into account the various factors that could have influenced stylistic choices. Moreover, this study will also contain in-depth style analyses in order to demonstrate the materializations of some of the tendencies suggested by the data.

In general, this study argues that CinemaScope had a clear impact on the production and style of 1950s Classical Hollywood films. Nevertheless, this shift did not affect what Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson have called the stylistic norms of the studio era. [13] The introduction of CinemaScope, as the analyses will demonstrate, challenged filmmakers to adapt to heavily changed working conditions, but it did not remove any basic stylistic options from their range of choices. It does, however, offer a very suitable case for analyzing how a phase of technological transition challenged the Hollywood system to show its flexible nature.

CinemaScope and Cinemetrics

In order to study the cutting rates and distribution of shot scales of 1950 CinemaScope films, this article adopts a method which is generally being labeled “statistical style analysis”.1 This refers to the systematic measuring and examining of quantifiable stylistic parameters in a sample of films. Scholars have applied this methodology onto a variety of formal elements, ranging from camera movement and shot scale to luminance and sound, employing manual as well as automatised measuring tools. [14] Many researchers in this field have used complex statistical methodologies in order to measure large samples of Hollywood films, and identify broad tendencies and non-obvious patterns. [15]

The method used in this study is more straightforward: in a first phase, the average shot lengths (ASL) and the distribution of shot scales in a sample of 1950s CinemaScope films were measured by using the digital tool Cinemetrics. Developed by Yuri Tsivian, Cinemetrics is “open-access interactive website designed to collect, store and process scholarly data about film”. [16] The measuring tool was originally designed to quantify cutting rates in films, but several scholars have used Cinemetrics to obtain data related to more complex parameters like shot scale, shot density or camera movement. The second phase entailed the identification of patterns within the obtained dataset. Subsequently, I sought to clarify these patterns by analyzing the production context and style of the films. Rather than employing complex statistical models, I aimed to provide film historical explanations for obvious tendencies within the data. Indeed, as Baxter has argued, the “statistical analysis of quantified filmic data is a means rather than an end”: it can highlight patterns and deviations, but these then need to be explained by film scholars. [17]

Although the currently available tools allow for several stylistic parameters to be measured, this study focuses on cutting rates (quantified as average shot length) and shot types or sizes (quantified as the distribution of shot scales). Salt has listed these as the most significant stylistic characteristics and the ones that lend themselves the most easily to quantitative analysis. [18] Additionally, both ASL and shot scale are relevant to examine in the context of CinemaScope, as they have been the most frequently commented upon by filmmakers, critics and scholars when discussing film style in anamorphic widescreen. While the distortion problems and poor light gathering power of the lenses made it difficult to shoot close-ups in CinemaScope, Fox trivialised this by claiming that the vast image could show great detail, thereby eliminating the need for close-ups. Even in shots with two or more characters, Zanuck argued, “each one of them seemed to be in an individual close-up”. [19] In addition, various trade press articles supported the elimination of the necessity to cut that CinemaScope prompted. President of the American Society of Cinematographers Charles G. Clarke for instance argued that it would be “more comfortable, interesting and natural to the spectator if scenes are sustained and a minimum of cuts are made”. [20]

This vision was quickly adopted by the film critical discourse, with Cahiers du cinéma and Movie becoming the most fervent advocates of the elimination of close-ups and explicit editing in CinemaScope. The French saw the style that the process seemed to encourage as one that would no longer manipulate reality, but at the same time provided more expressive resources to auteurs. [21] The vision of Movie was similar, with Charles Barr calling the CinemaScope style an alternative to “the explicit close-up/montage” approach, which allowed spectators less freedom to interpret “the meaning” of a scene. [22] Today’s critical discourse on CinemaScope style is to a large extent still shaped by these accounts. The systematic analysis of ASL and shot scale data below is therefore meant to serve as an empirical validation of the influential ideas on CinemaScope style that were launched by industry and press in the 1950s.

Sample Design

This study analyzes ASL and shot scale in 1950s CinemaScope by considering a representative selection films. Between 16 September 1953 (when The Robe, the first CinemaScope release, premiered) and December 1959, a maximum of 355 American CinemaScope films were released in the United States. As no comprehensive overview of all CinemaScope films using Bausch & Lomb lenses has been composed yet, this amount is based on two (not entirely accurate) lists: one that was published in the book Widescreen Movies, and another one that is available via the website The American WideScreen Museum. [23] Both include several post-1956 titles that were shot with superior Panavision lenses (mainly at MGM), as well as the 38 titles that were released as RegalScope pictures, which employed the exact same optics as CinemaScope, but were only used for low-budget films in black and white. All of these were removed from the list the sample was obtained from. [24]

The CinemaScope list displays a wide variety in terms of studios, genres and personnel. The 355 films were directed by 137 directors, filmed by 92 cinematographers and edited by 125 editors. Five of the eight major companies that dominated the studio era produced the large majority: Fox, MGM, Warner, Columbia Pictures Corporation and Universal-International. RKO Radio Pictures made only one film in Scope, while Paramount, having launched its own widescreen system VistaVision in 1954, did not produce a single one. United Artists was already mainly operating as a distributor for independently produced films, and therefore did not invest in CinemaScope films either. Of the 355 films, 68 were produced by smaller or independent production companies. Independent production increased considerably throughout the 1950s: in 1957 about 58 percent of the films released by the eight top studios were produced independently. [25]

In order to compose the sample while taking into account the diversity of the population, I have opted to rely on stratification, a process which divides the sample into sub-groups and then draws random samples from each of those. [26] The CinemaScope sample is stratified along two criteria: production company and release date. This generated 21 lists of films of which the sub-samples were drawn. Using a random number generator, each film was assigned a number between 0 and the total amount of films in the sub-group. Subsequently, the films with the highest numbers were selected. [27] This process produced a stratified CinemaScope sample (SCS) of 31 films.

In order to fully understand the meaning of systematically obtained data on film style, one needs to analyze them in a broader context. This stratified sample aims to provide a norm for analyzing cutting rates and shot scale in 1950s CinemaScope. As Salt argued, such a standard of comparison needs to reflect “the general technical and other pressures acting on the work of all filmmakers at that time and place. And ideally that requires the analysis of a large number of films, both good and bad, chosen completely at random”. [28] The measurements presented in this article will furthermore be compared to other datasets of 1950s Hollywood films in order to define the impact of the introduction of anamorphic widescreen on ASL and shot scale.

Average Shot Length and Genre: House of Bamboo

The producers, directors and cinematographers that praised the arrival of CinemaScope in trade journals predicted that the new process would eliminate fast cutting. Likewise, the critics of Cahiers and Movie avidly embraced the new emphasis on mise-en-scène Scope seemed to be creating instead. Several scholars have nonetheless used systematic measurements to demonstrate that the introduction of CinemaScope only had a minor impact on cutting rates. Salt, for instance, showed that the ASLs of Hollywood films had already begun to increase six years before The Robe premiered. [29] His dataset furthermore reveals that from 1955 onwards, filmmakers appeared to realise that rapid editing remained a feasible option in widescreen, as ASLs decreased again. Bordwell came to a similar conclusion: although the CinemaScope films he measured generally had higher ASLs than flat widescreen from the same period, the anamorphic process did by no means force filmmakers to abandon rapid successions of shots. [30] Initially, ASLs did become slightly higher, but those who preferred so could still rely on fast cutting. Both Salt and Bordwell saw how the classical continuity system restabilised from the mid-1950s onwards, as the quality of Bausch & Lomb lenses improved and filmmakers became accustomed to the new production conditions.

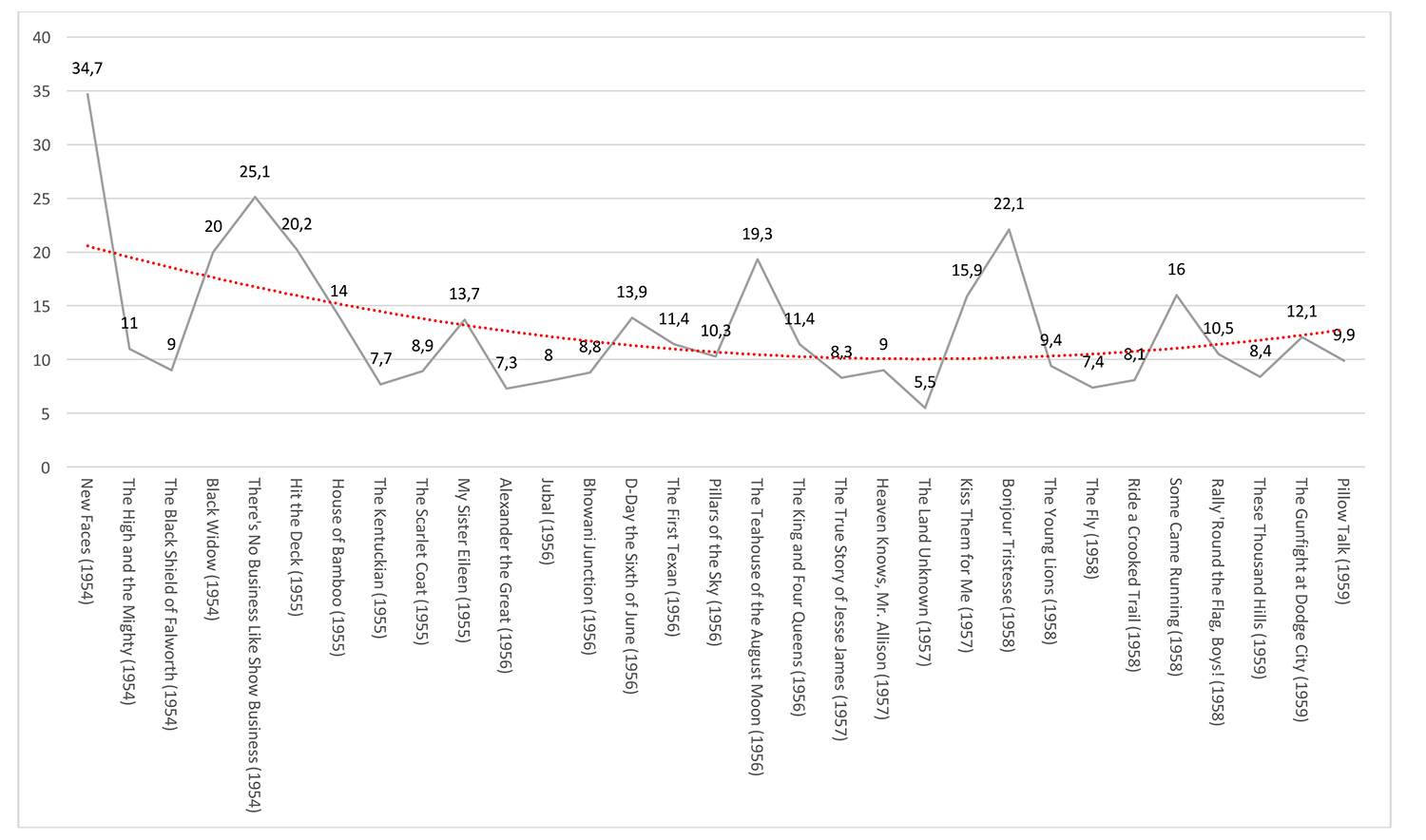

The ASL data of the SCS echo these findings. This study is, however, mainly concerned with patterns and fluctuations within the dataset of 1950s CinemaScope films. The combined ASL of the sample is 12,8 seconds, with over half of the films falling between 8 and 12 seconds. This is in line with the measurements presented by Bordwell and Salt. [31] The SCS data also suggest a decrease in the ASLs of CinemaScope films throughout the 1950s. [Table 1] This tendency, exposed by the second order polynomial trendline, is caused by improved equipment and a growing familiarity. In addition, it is illustrative of the broader trend towards intensified continuity in Hollywood studio films. According to Bordwell, the increase in cutting rates is one of the main indicators of this stylistic intensification, the start of which he situated in the late 1950s. [32]

Table 1: Average shot lengths of Stratified CinemaScope Sample (SCS) (ranked according to month of release)

Despite displaying easily recognizable patterns, the ASL dataset does contain a number of deviations. Some of those are directly related to the characteristics of certain film genres. Musicals and, to a lesser extent, comedies and melodramas generally have high ASLs, whereas spectacular genres like western, adventure and science-fiction are often cut faster. Three of the four slowest films in the sample are early Scope musicals: New Faces (Harry Horner and John Beale, 1954; 34.7 seconds), There’s No Business Like Show Business (Walter Lang, 1954; 25.1 seconds) and Hit the Deck (Roy Rowland, 1955; 20.2 seconds). The dynamic profiles of these films show the impact of their narrative structure on the cutting rates, indicating that the typical song and dance routines considerably raise the ASLs. Shootouts, chases and other action sequences have the opposite effect on the averages of western, adventure and science-fiction films, with the ten fastest films in the SCS (having ASLs between 5.5 and 8.9 seconds) all being examples of one of these genres. Furthermore, most of them were shot towards the end of the 1950s, when faster cutting rates were quickly regaining popularity.

House of Bamboo (Samuel Fuller, 1955), an early action-driven picture, has a remarkably high ASL of 14 seconds. Given the various tense heist scenes it contains, the data invite further explanation. Based on his available ASLs, Fuller appears to have been a relatively fast cutter. [33] However, as Lisa Dombrowski has written, the director preferred to “juxtapose long-take scenes with those reliant on montage”. [34] The prologue of the film, for example, shows the raid on a military train between Kyoto and Tokyo in a rapid succession of 31 shots, resulting in an ASL of only 4 seconds. [35] However, the film contains some notable long takes as well. Right before its climax, House of Bamboo even includes three successive sequence shots: a static two-shot in which gang leader Sandy Dawson (Robert Ryan) wrongly assassinates his henchman Griff (Cameron Mitchell) in his bathtub (74 seconds), a mobile crane shot that ends with Sandy’s informant Ceram (Sandro Giglio) informing him about the mistake (175 seconds), and finally a piece of ensemble staging as the gang prepares the robbery that will conclude the film (164 seconds). [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Fuller had a habit of shooting only one or two takes for each shot, which assigned greater responsibility to his editors, who often did not have sufficient material to conceal errors. [36] The editor’s personal style does not, however, appear to have caused the high ASL of House of Bamboo. James B. Clark also cut Fuller’s first CinemaScope picture the year before. With 9.8 seconds, Hell and High Water has a relatively low ASL, but this could be explained by the fact that large parts of the film take place on a submarine. Not unlike other early Scope pictures on board of vehicles, the camera is inevitably put close, as a result of which the cutting is faster: Beneath the 12-Mile Reef has an ASL of 10 seconds, The High and the Mighty (William A. Wellman, 1954) of 11 seconds. In his autobiography, Fuller recalled that “Fox executives were anxious to see if a CinemaScope movie could be made without gigantic sets and thousands of extras”. [37] Satisfied with the result, Zanuck screened Hell and High Water multiple times as an example of how to stage and cut a small-scale CinemaScope film. [38] House of Bamboo, in contrast, was Hollywood’s first-ever shot film in Japan, so the camera is put further and the shots are longer in order to show the exotic settings. Dombrowski noticed that both films “demonstrate Fuller’s ability to adhere fully to classical norms”. [39] His first two CinemaScope films indeed illustrate that, even more than individual preferences, genre, setting and narrative conventions had an impact on ASLs.

Average Shot Length and Staging: The True Story of Jesse James

Some filmmakers embraced CinemaScope in order to refine their stylistic signature. In the SCS, the ASLs of Vincente Minnelli (Some Came Running, 1958; 16 seconds) and Otto Preminger (Bonjour Tristesse, 1958; 22.1 seconds) stand out between the faster films of the late 1950s. [40] Both were neither influenced by genre conventions nor the different editors they worked with. Minnelli’s ASLs slightly went up after CinemaScope was launched. [41] Preminger’s ASLs rose more clearly, but after 1953 there is only a minor difference between his flat and anamorphic pictures. [42] On the other side of the spectrum, fast cutting directors like Nicholas Ray (The True Story of Jesse James, 1957; 8.3 seconds) and Richard Fleischer (These Thousand Hills, 1959; 8.4 seconds) demonstrated that the set of stylistic options filmmakers could rely on remained more or less the same. [43] Although Ray claimed that “the art of film has little to do with the art of editing”, numerous critics and scholars have stresses his idiosyncratic cutting methods. [44] V.F. Perkins, for instance, noted Ray’s use of “incomplete shots”, as a result of which “the montage becomes a pattern of interruption in which each image seems to force its way on to the screen at the expense of its predecessor”. [45] Jean-Luc Godard similarly described Ray’s “signature” by “the sudden insertion, in a scene with several characters, of a shot of one of them who is only participating indirectly in the conversation he is witnessing”. [46] Harper Cossar added that Ray did not adjust his editing style to CinemaScope, but rather “breaks his conversation sequences into familiar shot-reverse shot patterns that Preminger and others regard as belonging to the Academy ratio era”. [47]

Although the film was re-edited by Fox, the cutting rates of The True Story of Jesse James seamlessly fit into Ray’s recognizable ASL data. [48] Furthermore, Ray’s fast cutting did not prevent him from employing the width of the CinemaScope frame for the purpose of staging. A key scene depicts the moment Jesse overtakes his brother Frank as the leader of their gang. While the cutting is in line with the rest of the film (the scene lasts 165 seconds and has an ASL of 9.8 seconds), characters are constantly moved around, subtly entering and leaving zones of attention. The first shots present the gang of nine in two-shots and three-shots as the men consider how to react against the Northern sympathizers that have ruined their farms. As the critics quoted above wrote, several cuts abruptly move away from talking characters in order to focus on the reactions of others. When Frank announces that his younger brother has a plan, Ray switches to an establishing shot. This has Jesse in a central position, his face brightly lit by an oil lamp, as he proposes to rob a Yankee bank to compensate for their losses. [Figure 2] The next shot reveals the skeptical reaction of the Younger brothers, flanked by Frank in an aperture framing to their right. Subsequently, Jesse is pushed to the margin again, edge framed on the left side of a composition that is intersected by a wooden beam. Frank now occupies a central position on the other side of the beam. Cole Younger, spokesman of the farmers, distrusts Jesse’s plans, and firmly remains on Frank’s side. [Figure 3] But while the James brothers convince one farmer after another, Cole gradually moves to the center of the composition. When he is finally won over by Jesse’s strategy, the camera, for the first time in the scene, pans. This movement generates a new setup that emphasises the shifting roles within the gang: Frank is pushed to the right edge, while Jesse, now centralised, is joined by Cole on his side of the beam. [Figure 4] This scene is illustrative for Ray’s film style, and demonstrates that high cutting rates still allow filmmakers to develop complex widescreen choreographies.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

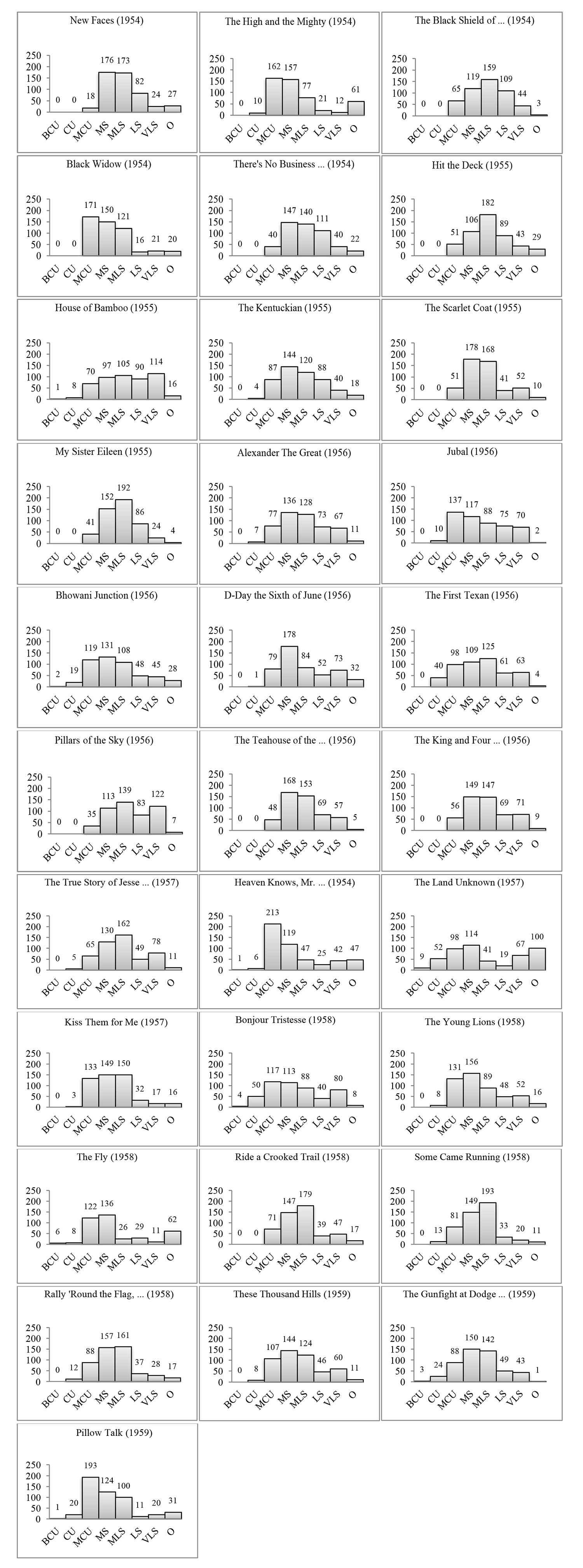

Shot Scale: Cutting off the Top and Bottom

Trade press articles abundantly described how CinemaScope would take away the need for close-ups, as the new format could provide more detail. [49] Critics, however, argued that the anamorphic widescreen process would not eliminate the close-up altogether. [50] They did, however, claim that it would discourage cutting in to closer shots to explicitly stress compositional details. [51] In order to provide a general overview of the distribution of shot scales in 1950s CinemaScope, the 31 films in the SCS have been subjected to a complete shot scale measurement. [52] [Table 2] The data confirm the decreased popularity of the close-up in CinemaScope. On average the films contain 10,8 big close-ups and close-ups per 500 shots. This is only half the amount that I measured in a fifteen film-sample of Fox films released from 1950 to 1953 (20,7 BCUs and CUs/500 shots) and a ten film-sample of comedies and melodramas released in the same period (22,8 BCUs and CUs/500 shots). [53]

Table 2: Scale of shot per 500 shots in CinemaScope comparison sample (ranked according to month of release)

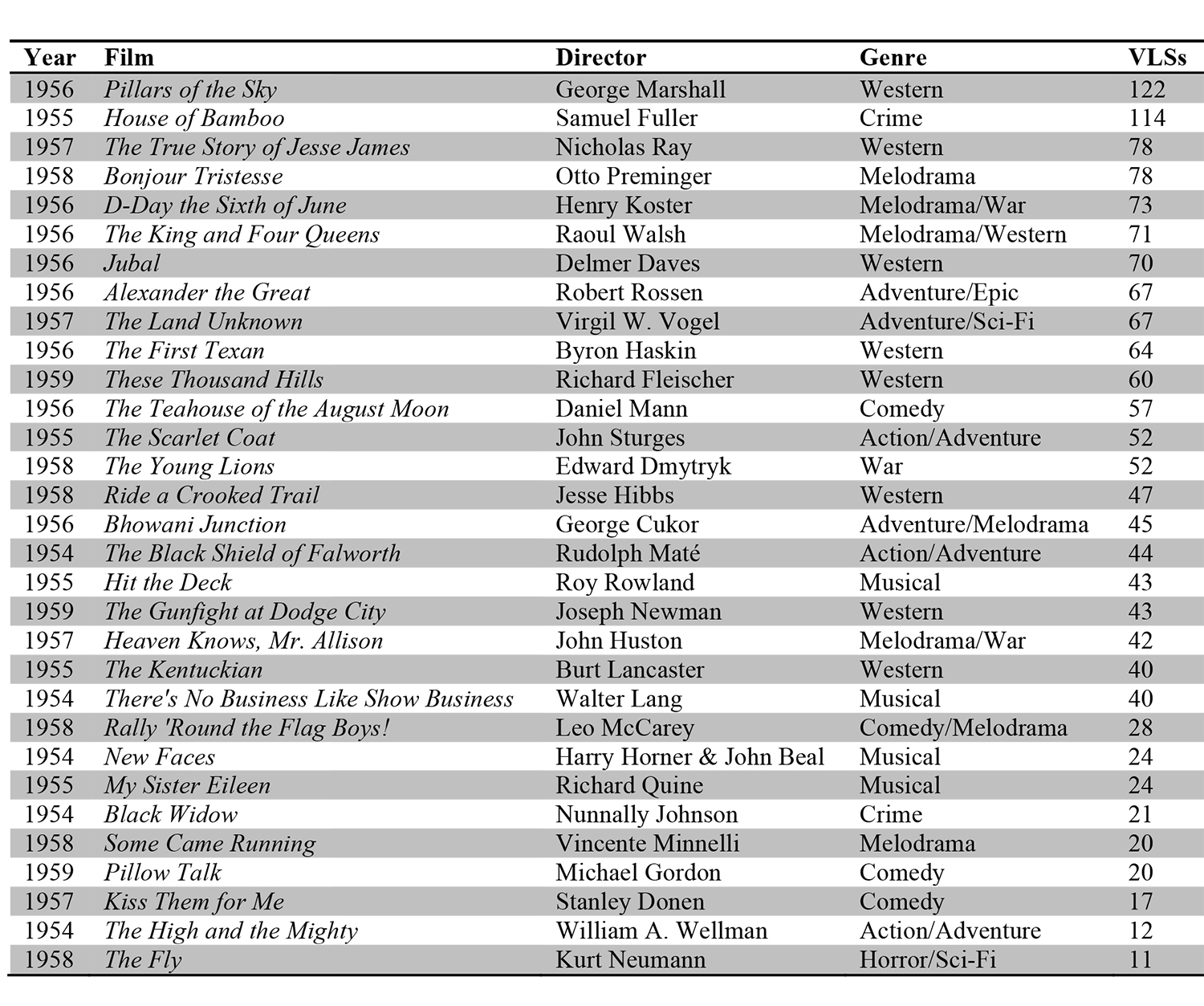

As with regard to ASLs, genre conventions urged filmmakers to use certain shot types more than others. The shot scale data show that spectacular genres such as western, war and adventure contain high amounts of very long shots, whereas melodramas and comedies are generally shot from closer. Given the outdoor settings and the important role of the landscape in many of the action-driven pictures, the shooting location is an even more accurate indicator of the amount of close and long shots. Of the ten films in the SCS with the lowest amount of very long shots, nine were filmed at the studio. Of the ten with the most very long shots, nine were shot on location. [Table 3] While some of these were recorded at studio ranches, others like House of Bamboo (Tokyo), Bonjour Tristesse (the Côte d’Azur) or Alexander the Great (Robert Rossen, 1956; Andalucía) were runaway productions. [54] Further down the list, exotic locations like Nara (Japan), Lahore (Pakistan) or Trinidad and Tobago lifted the amount of very long shots in more intimate films like The Teahouse of the August Moon (Daniel Mann, 1956) Bhowani Junction (George Cukor, 1956) and Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison (John Huston, 1957). [55] As Kate Fortmueller has explained, the high amount of very long shots in Bhowani Junction serves not only to showcase the setting, but also the various instances of non-violent collective action, with massive crowds gathering to protest against British rule. [56]

Table 3: Amount of very long shots per 500 shots in CinemaScope comparison sample (ranked from highest to lowest)

The relation between the amount of close shots on the one hand and the genre or shooting location on the other is less obvious: several pictures shot away from the studio figure among those with the most close-ups. Possible explanations for the abundance of close shots in these films are the development of improved lenses (Bausch & Lomb provided updated optical camera systems in 1954), but also the availability of natural light when shooting outdoors in sundrenched locations. [57] This partly solved the light gathering problems of the anamorphic lenses, allowing filmmakers to create depth compositions with reasonably close foregrounds. The film with the most close-ups in the SCS is The Land Unknown (Virgil Vogel, 1957), a black-and-white science-fiction film shot at Universal that contains various scenes of four expedition members packed together in a small helicopter (unsurprisingly, it is also the fastest film in the sample). [Figure 5] Similar setups explain the high number of close-ups and medium close-ups in the early Scope disaster film The High and the Mighty. The entire film takes place aboard an airliner, so the crew and passengers are constantly shot at close range. [Figure 6] For Cahiers, The High and the Mighty proved that CinemaScope would not cause the close-up to disappear. [58]

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Similar to the ASL data, the distribution of shot scales in the SCS suggests an initial period of acclimatization after which filmmakers slowly readopted their familiar practices. If we divide the SCS into two groups, ranked according to month of release, the data show a clear pattern: the first sixteen releases (1954-1956) contain only 6,4 big close-ups and close-ups, way less than the average of 15,5 in the second group (1956-1959). This restabilization can be explained by a growing acquaintance with the anamorphic technology, and the availability of better Bausch & Lomb lenses, that allowed filmmakers to put the camera closer than initially prescribed by the studios.

For some, tighter framings were just a logical consequence of the shift to widescreen. Despite directing all of his nine 1950s widescreen pictures in CinemaScope, Minnelli claimed that the format did not have “a shape that makes much sense”. Cutting off the top and bottom of a regular composition, CinemaScope, according to the director, reduced the visual field vertically, rather than extending it horizontally. [59] Most flat widescreen ratios were created by letterboxing an Academy ratio picture during shooting, printing or projecting. [60] This could change the shot size, turning, for example, medium close-ups into close-ups. As Minnelli’s quote suggests, several creatives seemed to have adopted a similar approach when working with CinemaScope. Some of the drawings that production designer Ward Ihnen made in preparation for The King and Four Queens (Raoul Walsh, 1956) indeed display squarer compositions with the top and bottom cut off. [61] The storyboards for Jubal (Delmer Daves, 1956), produced by art director Carl Anderson, reveal a similar tactic: various layouts are designed in a format less wide, but have a CinemaScope frame imposed on them, reducing the height of the composition. [62] These drawings offer yet another illustration of the various ways in which the introduction of CinemaScope urged filmmakers to move between formal continuity and adaptation.

Conclusions

This article aimed to provide a general overview of the cutting rates and the distribution of shot scales in 1950s CinemaScope. Measuring and analyzing the two stylistic parameters that had been discussed the most frequently in trade papers and critical journals of the 1950s, it looked for patterns and deviations within the data. Subsequently, I tried to provide explanations for these tendencies, by considering aspects like genre conventions, narrative structures, individual preferences and release dates. Examining the form as well as the production context of the films, this study tried to answer two questions: how do 1950s CinemaScope pictures look, and why do they look like that?

The methodology used in this article is layered. The data collection and initial analysis are quantitative, building further on previously conducted studies within the realm of statistical style analysis. Additionally, extensive archival research and multiple film style analyses provided explanations for particular tendencies. Indeed, in order to really understand what such data indicate, one needs to situate them in broader contexts, relying one, what Donato Toraro has called “contextual statistical analysis”. [63] Such an approach implies taking into account comparable samples, but also considering the production process and the internal dynamics of the films. This method can help us to understand how and why particular choices were made, and what their stylistic implications were.

This methodological model is easily transferable to other regions and timeframes. It is particularly useful for revealing the stylistic norms in a demarcated period, which the work of individuals or studios can subsequently be compared with (as is the aim of this project). It is evident that film style entails a lot more than cutting rates and shot types, and, even more important, that it cannot be reduced to isolated components. While the digital tools that scholars have at their disposal are evolving quickly, other stylistic elements are not as easily quantifiable as ASL and shot scales. However, the layered approach that characterises a contextual statistical style analysis allows researchers to take into account other formal elements as well. The scene analysis of The True Story of Jesse James, for example, shows how to relate ASL data to staging and shot composition. Even more importantly, it demonstrates that stylistic elements do not exist in a vacuum, but interact continuously, something this methodological model aims to acknowledge.

Acknowledgements

I thank the Research Fund – Flanders (FWO) for financially supporting my research stays in Los Angeles and in New York City. I am particularly grateful to Louise Hilton of the Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Ned Comstock of the Cinematic Arts Library at the University of Southern California (USC), and Jennifer B. Lee of the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University.

Short bio

Sam Roggen is a guest lecturer in Film Studies and Visual Culture. He is a member of the Visual and Digital Cultures Research Center (ViDi, University of Antwerp). Sam holds a doctoral degree in Film Studies and Visual Culture (Antwerp, 2018). His articles on film style, film technologies and Classical Hollywood cinema have been published in such journals as Projections, Screening the Past, LOLA, The Journal of British Cinema and Television, the New Review of Film and Television Studies and the Quarterly Review of Film and Video. sam.roggen@uantwerpen.be

Endnotes

[1] Cobbett Steinberg, Reel Facts: The Movie Book of Records (New York: Vintage, 1978), p. 371.

[2] John Izod, Hollywood and the Box Office 1895-1986 (London: Macmillan Press, 1988), p. 143.

[3] Douglas Gomery, The Hollywood Studio System: A History (London: BFI Publishing, 2005), p. 123.

[4] Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century-Fox: A Corporate and Financial History (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1988), p. 79.

[5] Murray Pomerance, American Cinema of the 1950s: Themes and Variations (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2005), p. 8.

[6] Izod, Hollywood and the Box Office, p. 132.

[7] Peter Lev, Transforming the Screen 1950-1959 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), p. 212.

[8] Tino Balio, Hollywood in the Age of Television (London: Routledge, 1990), p. 3; Solomon, Twentieth Century-Fox, p. 82.

[9] John Belton, Widescreen Cinema (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press) pp. 121-122; See also Albert Arnulf, “Henri Chrétien (1979-1956)”, Film History Vol. 15 No. 1 (2003), pp. 5-10.

[10] For a detailed overview of the anamorphic technology and restrictions of the CinemaScope system, see Belton, Widescreen Cinema, pp. 138-148.

[11] Jack Warner to John Huston, letter, 19 February 1954, folder 374, John Huston Papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; Stuart Byron and Martin L. Rubin, “Elia Kazan Interview”, Movie No. 19 (1971), p. 8.

[12] Jack Clayton to Jack Warner, letter, n.d., folder 374, John Huston Papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

[13] David Bordwell, Janet Staiger & Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style & Mode of Production to 1960 (London: Routledge, 1985).

[14] Barry Salt, “Statistical Style Analysis of Motion Pictures”, Film Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1 (1974), pp. 13-22.

[15] On camera movement, see Barry Salt, “The Shape of 1999: The Stylistics of American Movies at the End of the Century”, New Review of Film and Television Studies Vol. 2 No. 1 (2004), pp. 61-85. On shot scale, see Sergio Benini, Michele Svanera, Nicola Adami, Riccardo Leonardi & András Bálint Kovács, “Shot Scale Distribution in Art Films”, Multimedia Tools and Applications Vol. 75 No. 23 (2016), pp. 16499-16527. On luminance, see James E. Cutting, Kaitlin L. Brunick, Jordan E. Delong, Catalina Iricinschi & Ayse Candan, “Quicker, Faster, Darker: Changes in Hollywood Film over 75 Years”, i-Perception No. 2 (2011), pp. 569-576. On sound, see Nick Redfern, “The Time Contour Plot: Graphical Analysis of a Film Soundtrack”, (Paper presented at the Sound and the Screen Conference, University of West London, 20 November 2015).

[16] Yuri Tsivian, “Cinemetrics, Part of the Humanities’ Cyberinfrastructure”, in Michael Ross, Manfred Grauer & Bernd Freisleben (eds), Digital Tools in Media Studies: Analysis and Research. An Overview (New Brunswick: Transaction, 2009), p. 93.

[17] Baxter, “Evolution in Hollywood Editing Patterns?”.

[18] Barry Salt, Moving into Pictures: More on Film History, Style, and Analysis (London: Starword, 2006), p. 14.

[19] Darryl F. Zanuck to Nunnally Johnson & Jean Negulesco, memo, 17 March 1953, folder 25, Jean and Dusty Negulesco Papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The argument that the size of the CinemaScope image made close-ups unnecessary can be found countless times in 1950s trade press articles. See also Charles G. Clarke, “Practical Filming Techniques for Three-Dimension and Wide-Screen Motion Pictures”, American Cinematographer Vol. 34 No. 3 (1953), pp. 107, 128-129, 138; Henry Koster, “Directing in CinemaScope”, in Martin Quigley, Jr. (ed), New Screen Techniques (New York: Quigley, 1953), pp. 171-173; Leon Shamroy, “Filming ‘The Robe’”, in Quigley, New Screen Techniques, pp. 177-180.

[20] Charles G. Clarke, “CinemaScope Photographic Techniques”, American Cinematographer Vol. 36 No. 6 (1955), p. 362. See also Leon Shamroy, “Filming the Big Dimension”, American Cinematographer Vol. 34 No. 5 (1953), pp. 216-232; Jean Negulesco, “New Medium – New Methods”, in Quigley, New Screen Techniques, pp. 174-176; “CinemaScope Didn’t Just Happen”, Action Vol. 14 No. 7 (1953), pp. 4-7.

[21] André Bazin (trans. Catherine Jones & Richard Neupert), “Will CinemaScope Save the Cinema?”, The Velvet Light Trap No. 21 (1985) pp. 8-14; Jacques Rivette (trans. Liz Heron), “The Age of metteurs en scène”, in Jim Hillier (ed), Cahiers du Cinéma, the 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), pp. 275-279.

[22] Charles Barr, “CinemaScope: Before and After”, Film Quarterly Vol. 16 No. 4 (1963), p. 17.

[23] Robert E. Carr & R.M. Hayes, Wide Screen Movies: A History and Filmography of Wide Gauge Filmmaking (Jefferson: McFarland, 1988), pp. 91-103. The website The American WideScreen Museum is curated by Martin Hart and offers extensive information on several widescreen processes. See http://www.widescreenmuseum.com

[24] As most Panavision titles released between 1956 and 1959 carry the CinemaScope trademark as well, it is possible that the list of 355 films still includes some films shot with Panavision. Whenever I encountered a CinemaScope picture filmed with Panavision lenses, it was removed from the list.

[25] Balio, Hollywood in the Age of Television, p. 10.

[26] Patrick Sturges, “Designing Samples”, in Nigel Gilbert (ed), Researching Social Life (Los Angeles: Sage, 2008), p. 176.

[27] On 4 January 2014, 277 of the 355 films in the list were available on VHS, DVD, Blu-ray or via video on demand services. Whenever an unavailable film was included in the sub-sample, it was removed and replaced by the next film on the list.

[28] Barry Salt, Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis (London: Starword, 1983), p. 219.

[29] Ibid., p. 246.

[30] David Bordwell, “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses”, in Poetics of Cinema (London: Routledge, 2007), p. 304. The distinction between anamorphic widescreen on the one hand and ‘flat’ widescreen on the other hand originated immediately after the launch of CinemaScope. Creating a wide angle experience on the concave Miracle Mirror screen, CinemaScope promised spectators a better, more immersive version of 3D. This article will repeatedly refer to non-anamorphic widescreen films as ‘flat’ films. See Clarke, “CinemaScope Photographic Techniques”, p. 336.

[31] Bordwell, “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses”, p. 304; Barry Salt, “The Shape of 1959”, New Review of Film and Television Studies Vol. 7 No. 4 (2009), p. 403. Bordwell measured 68 CinemaScope films from 1954 and 1955: 30% to 40% of these had ASLs between 8 and 12 seconds. ‘About a third’ had ASLs between 12 and 19.9 seconds. Nine had ASLs higher than 20 seconds. A fifth had ASLs lower than 8 seconds. In the period 1956 to 1960, two thirds of the films he measured had ASLs between 7 and 13 seconds, marking a shift towards faster cutting rhythms. Salt measured the cutting rates of 7448 Hollywood films released between 1930 and 2005, without specifying the amount of CinemaScope films. The total ASLs for the years 1953-1959 (so not exclusively CinemaScope films) all fall between 9 and 11 seconds. The samples Salt and Bordwell have used are neither random nor stratified, which makes them less representative of the entire population of 1950s CinemaScope pictures.

[32] David Bordwell, “Intensified Continuity: Visual Style in Contemporary American Film”, Film Quarterly Vol. 55 No. 3 (2002), p. 16.

[33] Ten of the twelve films Fuller directed in the 1950s have been measured by Cinemetrics users. Eight of them have an ASL that is lower than twelve seconds. The two exceptions are House of Bamboo and Park Row (1952), a completely self-financed film Fuller shot while on leave from Fox and the only film in his oeuvre that he was able to write, direct, and produce in complete independence. All Cinemetrics measurements are available through the database at http://cinemetrics.lv/

[34] Lisa Dombrowski, The Films of Samuel Fuller: If You Die, I’ll Kill You! (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2008), p. 17.

[35] Despite the fast cutting in the pre-credits robbery, the scene displays a lot of attention for colour and composition, with the black train in the snowy landscape echoing the colours of Mount Fuji in the background. See Gerald Peary (ed), Samuel Fuller: Interviews (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2012), p. 23.

[36] Dombrowski, The Films of Samuel Fuller, pp. 19-20.

[37] Samuel Fuller, Christa Lang Fuller & Jerome Henry Rudes, A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting and Filmmaking (New York: Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, 2004), p. 313.

[38] Darryl F. Zanuck to Hedda Hopper, letter, 16 January 1954, folder 3292, Hedda Hopper Papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; Darryl F. Zanuck to all contract directors, all contract producers, all contract cameramen and Earl Sponable, memo, 26 January 1954, folder 25, Darryl F. Zanuck folder, box 116, Earl I. Sponable Papers, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries.

[39] Dombrowski, The Films of Samuel Fuller, p. 77.

[40] On CinemaScope staging in Bonjour Tristesse, see Christian Keathley, “Bonjour Tristesse and the Expressive Potential of Découpage”, Movie: A Journal of Film Criticism No. 3 (2011), pp. 67-72.

[41] Twelve of the fifteen films Minnelli directed in the 1950s have been measured by Cinemetrics users. They all have ASLs between 15 (The Long, Long Trailer; 1954) and 31,9 seconds (his first CinemaScope picture Brigadoon; 1954). Five pre-widescreen films have a total average of 19.7 seconds, seven CinemaScope films one of 21.5 seconds.

[42] Ten of the thirteen films Preminger directed in the 1950s have been measured by Cinemetrics users. They all have ASLs between 13.3 (Anatomy of a Murder; 1959) and 46 seconds (Carmen Jones, the slowest CinemaScope film anyone has measured; 1954). Three pre-widescreen films have a combined total average of 14.5 seconds, four CinemaScope films one of 25.4 seconds, three flat widescreen pictures one of 23.3 seconds.

[43] Cinemetrics has ASL data of sixteen of the films that Ray and Fleischer directed in the 1950s. Both have only one film with an ASL higher than ten seconds: Bigger than Life (10.6 seconds) and Compulsion (10.6 seconds), both shot in CinemaScope. While Harper Cossar claims that Ray’s visual poetics changed in the widescreen era, his cutting rates seem to have been affected barely by the variety in aspect ratio or genres in which the director worked throughout the 1950s. See Harper Cossar, “Ray, Widescreen, and Genre”, in Steven Rybin & Will Scheibel (eds), Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground: Nicholas Ray in American Cinema (New York: State University of New York Press, 2014), p. 190.

[44] Nicholas Ray & Susan Ray (ed), I Was Interrupted: Nicholas Ray on Making Movies (Berkeley: University of California Press), p. 42.

[45] V.F. Perkins, “The Cinema of Nicholas Ray”, Movie No. 9 (1963), p. 65.

[46] Jean-Luc Godard (trans. Tom Milne), “Le Cinéaste bien-aimé”, in Tom Milne (ed), Godard on Godard: Critical Writing by Jean-Luc Godard (New York: Da Capo, 1986), pp. 60-61.

[47] Harper Cossar, Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema (Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 2011), p. 122.

[48] Geoff Andrew, The Films of Nicholas Ray: The Poet of Nightfall (London: BFI Publishing, 2004), p. 111.

[49] One must take into account that trade press and critical articles sometimes used diverse definitions when referring to a close-up. Some of these seem to have been based on the size of the screen on which the film was projected. An often-quoted Time Magazine review of The Robe mentioned, for instance, that “in CinemaScope close-ups, the actors are so big that an average adult could stand erect in Victor Mature’s ear.” Given that a Miracle Mirror screen, developed for the projection of CinemaScope, could be up to 24 feet high, an average adult would have been able to stand erect in Mature’s ear when the actor was shot in medium close-up or even medium shot. See “The New Pictures”, Time Magazine, 28 September 1953, accessed May 23, 2017, http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,818950-2,00.html

[50] André Bazin (trans. Dudley Andrew), “The Trial of CinemaScope: It Didn’t Kill the Close-Up”, in Dudley Andrew (ed), André Bazin’s New Media (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), pp. 294-298.

[51] Barr, “CinemaScope: Before and After”, p. 17.

[52] In order to measure the shot scale, the size of the human figure depicted within the frame is determined in relation to the height of the frame. This generates a division into seven possible shot sizes. A big close-up (BCU) includes only the head of the figure, while a close-up (CU) contains at least its head and shoulders. A medium close-up (MCU) shows the body from the waist and elbows upward, a medium shot (MS) displays it from the hips and wrists upward, and a medium long shot (MLS) covers it from the knees upward. A long shot (LS) shows the body of a standing figure in its entirety, whereas a very long shot (VLS) is every shot that contains more than merely the full height of the figure. An eighth category, labeled ‘Other’ (O), is used in order to register all shots that do not contain a human face. These might take the form of empty landscape or interior shots but also insert shots of objects or body parts other than the human face.

[53] Sam Roggen, “CinemaScope and the Close-Up/Montage Style: New Solutions to Familiar Problems” (unpublished manuscript); Sam Roggen, “The Air Around Faces: Clothesline Staging and Modern Urban Style in 1950s CinemaScope” (unpublished manuscript).

[54] Parallel with the launch of widescreen cinema, the phenomenon of the runaway production flourished. The reasons for its popularity – Hollywood doubled its amount of runaway productions in the 1950s – were diverse. After the second World War, various countries tried to attract foreign investments in order to stimulate their domestic film industry. Hollywood studios were attracted by tax breaks and production subsidies abroad. It also gave them an opportunity to escape the jurisdiction of the unions. In addition, blacklisted artists and craftspeople that lived in exile outside the U.S. could contribute more easily to pictures that were filmed abroad. Finally, runaway productions were also encouraged by “the lifestyle choices of Hollywood’s globe-trotting and capricious elite.” See Camille Johnson-Yale, A History of Hollywood’s Outsourcing Debate: Runaway Production (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2017), p. 3.

[55] While Bhowani Junction is set in India, shooting moved Lahore, when the Indian government declined the MGM production.

[56] Kate Fortmueller, “Encounters at the Margins of Hollywood: Casting and Location Shooting for Bhowani Junction”, Film History Vol. 28 No. 4 (2016), p 112.

[57] An announcement written by Earl I. Sponable, Director of Research at Fox, mentions six improvements in comparison with the first generation of anamorphic Bausch & Lomb lenses: improved resolving power, better depth of field, better flatness of field, corrections of optical aberrations, the addition of a single control to manage the objective lens and its anamorphic attachment simultaneously, and an extended assortment of focal lengths. See Earl I. Sponable, “New CinemaScope Camera Lenses”, 1954, box 106, Earl I. Sponable Papers, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries. See also Charles R. Daily, “Progress Committee Report for 1955”, Journal of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers Vol. 65 No. 5 (1955), p. 226.

[58] Bazin, “The Trial of CinemaScope”, p. 297.

[59] Mark Shivas, “Minnelli’s Method”, Movie No. 1 (1962), p. 23.

[60] Not all flat widescreen formats were created by masking the top and bottom of the picture. Paramount’s VistaVision ran 35mm film through the camera horizontally, generating a wider and finer-grained negative area. Adjusting the shape of the negative, VistaVision foreshadowed the development of notable wide gauge formats like Todd-AO or Super Panavision 70.

[61] Ward Ihnen, “Drawings for The King and Four Queens”, 1956, folder 8, Ward Ihnen Collection, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

[62] Carl Anderson, “Storyboards Jubal”, n.d., folder 24, Carl Anderson Papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

[63] Donato Toraro, “Reflections on the Pickpocket Statistical Analysis”, Offscreen Vol. 8 No. 4 (2004), accessed December 20, 2018, http://offscreen.com/view/pickpocket.