(‘Tex Arcana: The Cartoons of Tex Avery’, first published in Gerald Peary & Danny Peary (eds) The American Animated Cartoon: A Critical Anthology New York: Dutton, 1980. Republished with permission of the estate of Ronnie Scheib.)

[To some admirers, he is, after Disney, the single most important figure in the history of animation, a surrealist genius whose self-reflective intrusions into his cartoons are no less sophisticated than Brecht’s “alienating” devices. To others (bluenoses especially) Fred ‘Tex’ Avery represents everything loathsome about cartoons, from exaggerated violence to extra-corny sight gags, from outrageous silliness to crude sexual innuendo. Avery would not deny the charges, but would revel in them. Avery’s idea of a gag: “a guy would no sooner get hit with an anvil than he takes one step over and falls in a well.” His thoughts on anthropomorphic realism: “… we used any kind of distortion that couldn’t possibly happen.” About characterisation: “I’ve always felt that what you did with a character was more important than the character itself. Bugs Bunny could have been a bird” (Joe Adamson, Tex Avery: King of Cartoons).

Avery admits he was never a great artist; so he became a director instead, working at Warners between 1936 and 1942 and creating cartoon history. His animations are as much a part of the famed Warner Brothers style as those proletariat roustabout movies of Cagney, Bogart, and Pat O’Brien, short on bombast and budget but high on energy, speed, inner-city urbanity, and sheer wit. Avery directed the first real Bugs Bunny cartoon, A Wild Hare (1940) and it was he who planted “What’s Up, Doc?” in Bugs’s repertoire. He invented Porky Pig and Daffy Duck (and later, elsewhere, Droopy and those bizarre bugs killed off in Raid commercials). He trained Bob Clampett and Chuck Jones as his animators (and Bob Cannon too, of UPA McBoing-Boing fame) and his influence on their work is immeasurable. To trace only one line, of many: Jerry Lewis learned his cartoonish visual style from the best director of Martin and Lewis vehicles, Frank Tashlin; and Tashlin, of course, learned to make live-action narratives by directing cartoons at Warners in the “wild and woolly” Avery tradition. As Tashlin told Mike Barrier: “I would never once think I was ahead of Tex, anytime, anyhow. Tex was just marvellous.”]

In Believe It or Else (1939), one of Tex Avery’s Warners cartoon takeoffs on the newsreel doco format, Egghead, an early, recurring Avery standby, hero by default, divine retribution, or insistent incongruity, periodically pops up for short walk-ons protesting “I don’t believe it” or, for variation, bearing a sign proclaiming It’s a Fake. “Suspension of disbelief,” Coleridge’s aesthetic equivalent of soft lights and music, is hardly a mainstay of Avery’s oeuvre. Yet, as Greg Ford makes clear, the “anything-is-possible-in-these-here-cartoon-pictures” implosive bag of tricks Avery developed at Warner Brothers would be inconceivable without the bedrock foundation of believability and solidity Disney brought to the sound cartoon. For Avery’s mind-wrenching reversals, inversions, and violations of physical and psychological laws are only possible if these laws exist. Gravity, cause and effect, logic, subjectivity, personality, all the Disney-incorporated processes must weave their web of expectations, their dream of continuity, to set the stage for the violent shock of awakening that shudders through an Avery cartoon. Associations run wild, metaphors take on a life of their own, as the world of the mind in all its analytic clarity and preconditioned consciousness-streaming, its waking stupor and madly creative slumber, collides head-on with the world of the physical in ways that are only possible in “these here cartoony pictures,” although no one knew it before Avery and no one could forget it after him.

Almost from his arrival at Warners in 1936, the cute little pigs, squirrels, cats, bugs, and mice of the collectivistic Merrie Melodies and the bumpkin barn-yard “stars” of the more narrative Looney Tunes lost much of their wide-eyed innocence as the cartoons took on a new audacity, the pace quickened, and gags telescoped into gags. In as typical a Merrie Melodies as Penguin Parade (1938), one of Avery’s many forays into the Frozen North (until by poetic injustice he wound up with the thankless Chilly Willy at Lantz), a penguin orders a Scotch and soda, with a lemon twist, and the bartender promptly picks him up, pours in the proper ingredients and shakes briskly, producing instant inebriation. An aspiring swami in Hamateur Night (1938) confidentially thrusts swords into a basket containing an audience volunteer, then, after peeking into the ominously quiet receptacle, hands it gravely to the usher intoning “Give this gentleman his money back.” In the midst of fully orchestrated and choreographed renditions of whatever Warner Brothers tune a particular Merrie Melodies was pushing, characters suddenly freeze into grotesque attitudes in Avery’s early plays with the extreme “extremes” that were to become the hallmark of his work at MGM.

Avery’s films at Warners were generally structured around parody of an existing film or cartoon genre, the impact of his gags tending to explode the fundamental assumptions underlying these genres. Thus the “documentaries,” a series Avery invented at Warners, composed of spot gags gathered under a mock-monolithic “subject” and glued together by an omniscient, paternalistic narrator, targeted a simplified condensed world of analogy that, under the guise of education, unifies all things under the sun until the unknown becomes an exploitable variation on the known. Avery short-circuits the deadening “everything’s-basically-the-same-as-us-but-not-as-good” effect of such analogy by blatantly literalizing the implicit equation (whether between animals and humans or America and other cultures): a shapely female lizard in Cross-Country Detours (1940) sheds her skin – peeling it off slowly in time to slinky striptease music; by sudden reversals: one of the “primitive” inhabitants of The Isle of Pingo Pongo (1938) turns to snap a picture of the condescension-oozing narrator; or analogy-stretching word association: a frog croaks — by blowing its brains out with a revolver, destroying in the process that basic belief of the documentary that “seeing is believing.” Voice-over narration’s overly patient, overly “bright” tone, generally reserved for madmen, morons, children, and documentary film audiences, also affords Avery some great narrator/audience gags, including mad, unreadable diagrams “explaining” football formations (Screwball Football [1939]), a patently nonexistent optical illusion, in proof of which the audience is told to close one eye (half the screen blacked out), then the other (all black), and admonished “no peeking” as a slit opens on the screen (Believe It or Else), and the cap-off in Cross-Country Detours a split screen, on one side “for the adults” a horrible gila monster and, on the other, “for the kiddies,” a recitation by Shirley Temple of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” until Shirley, demolishing the split-screen line, frightens the gila monster away.

Heroes and Other Walk-Ons

In Hamateur Night, Egghead, who has sporadically interrupted the scheduled acts with his unsolicited renditions of “She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain,” is awarded the prize by popular acclaim – cut to an audience composed of hundreds of frantically cheering Eggheads, one of Avery’s many evocations of the nightmare of conformity and a fair indication of his assessment of his audience and their need for identification.

It is this need that Avery consistently refused to satisfy (although coming close enough to spawn the two greatest Warners stars, Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck), choosing instead to put into question the very idea of a hero. In The Village Smithy (1936) the narrator (reputedly and significantly the first offscreen narrator in cartoon history) interrupts his out-of-sync rendition of the Longfellow poem to introduce, for a split second, “our hero-Porky Pig.” In Little Red Walking Hood (1937) Egghead appears unexplainedly in the goshdurndest places, whistling a tune and toting a violin case, and when finally challenged by the legit cast, “Who the heck are you anyway?,” replies, “I’m the hero in this picture,” extracting a mallet from his case and clobbering the villain.

For it was particularly the popularized fairy tale, with its whole apparatus for suspension of disbelief in a self-enclosed, coded never-never land, the innocuous “children’s world” of boxed-off fantasy, replete with hero, villain, damsel in distress, local colour, happy ending, and sugar-coated moral, minus only the sexual terror, death, and repressed fears of the original, that inspired Avery’s most elaborate audience rug-pullers. A split-screen phone call from Red Riding Hood to Goldilocks warning of the Wolf’s imminent arrival (A Bear’s Tale [1940]), a Grandma/Wolf chase interrupted by a telephoned grocery list (“one dozen eggs, a pound of butter, a head of lettuce, and a pint of gin”) in Little Red Walking Hood, giant flashing neon signs, a drunk fairy godmother delivered in a police van, trumpeting royal pages breaking into a rousing chorus of “She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain” (Cinderella Meets Fella [1938]) are but a few of the little context-destroyers Avery introduced at Warners and continued at MGM. In Who Killed Who (1943) the victim, so designated by a large neon sign on the back of his of chair, is discovered reading a book titled Who Killed Who – From the Cartoon of the Same Name. Characters pause to comment on the action: “Do these things happen to you girls out there?” “I do things like this to him all through the picture.” “Heh, kissed a cow.” “I like this ending. It’s silly.” A seemingly endless series of identical tied-up butlers topple out of a closet like a riffled deck of cards in Who Killed Who, one pausing long enough to comment, “Ah yes, quite a bunch of us, isn’t it?”

Even corny, forced gags, fully admitting their compulsive nature, become funny in the teller’s relation to it (in Land of the Midnight Fun [1939]) a timber wolf alternately cries “Timber” and cracks up at the idea, knowing full well the joke’s on the audience), or in complicity they create with the audience (a skunk in Porky’s Preview [1941]), asked for a five-cent admission, replies, “I only have one [s]cent,” turning to the audience with a winked “get it?”). Little signs spring up commenting “Corny gag, ain’t it?”, or “Monotonous, isn’t it?”

“Hey You, in the Third Row!”

For Avery never lets his audience forget they are watching a cartoon, filling his films with cartoon-reality jokes, even portraying the audience in the film. Shadow figures of audience members play prominent roles in the action, creating cartoons-within-cartoons (one audience member turns informer in Thugs with Dirty Mugs [1939]), blurring all frame-line distinctions (Prince Charming has no sooner found Cinderella’s note informing she has gone to see a movie in Cinderella Meets Fella, than she calls out, “Yoo hoo, here I am in the tenth row,” and her shadow figure makes its way through the audience to join him on the screen). Bugs Bunny comes out to read the title credits of Tortoise Beats Hare (1941), a false-start opener Avery was to use repeatedly at M-G-M. Swingshift Cinderella (1945) begins with the wolf chasing Red Riding Hood through the woods and past the credits before they realise they’re in the wrong cartoon. A quarter of the way through Batty Baseball (1944) one player stops the action, demanding the MGM lion and opening credits, which haven’t yet appeared. The cartoon-reality gags become wilder and wilder at MGM, as characters race past sprocket holes into a white void, cross Technicolour line into black and white, or reach down to pluck out an animated projection hair.

“Look Fellas — I’m Dancing”

The most disorienting and absurdist gags in a Warners Avery still refer mainly to the fun of cartooning, a fun the audience is invited to share fully, in heightened consciousness of the possibilities of an ever-changing perspective. The increasing abstraction and plays with means of representation permit a liberation from the enclosure of believability and a delight in the process of animation, movement, change. Yet it seems obvious, at least in hindsight, that by 1940 Avery was beginning to chafe a bit at the strictures imposed by the Merrie Melodies format and childlike circle-upon-circle character design that persisted (with notable exceptions, chief among them Avery’s invention of and design for Bugs Bunny)into the early 1940s. Avery’s last Porky pic, Porky’s Preview, a hilariously ingenuous cartoon-within-a-cartoon, constitutes both a loving parody of a Merrie Melodie and a celebration of the wondrous possibilities of animating any design, no matter how rudimentary. It is a magnificently animated film, for all its deliberately “crudely drawn” stick figures, childish inverted lettering, mock-primitive sloppiness (a train with infinitely expandable wheels zips up and down mountains and past a THE END sign, no end to this frame line), overly visible process of production (a riotously forced-sync Mexican dancer, frozen until the music starts, animated, crossed-out, reanimated, recrossed-out and, when choreographic ingenuity runs dry, is whirled weightless through the air in time to the circular beat), Grand Finale of “September in the Rain” with a rain cloud that rushes back on cue, and fully justifies the obvious pride of its creator, Porky Pig whose cross-eyed self-portrait labelled “me” frequently appears alongside a matching approximation of the audience ticketed “you”), who explains modestly, “Shucks, it wasn’t hard ’cause I’m an artist.”

The Shield and the Lion

This is not to say that cartooning ceased to be fun when Avery moved to MGM in 1942, or that the cartoons he made there are any less funny. Quite the contrary. But they are far more disturbing, more manic, the world they portray is increasingly fragmented, as indeed was the world after the war. If the Warners films continually reintroduced elements incongruous to the repressive enclosure of “suspension of disbelief,” bringing the audience in on the joke, never letting it evade the freedom of consciousness, the MGMers unleashed repressed psychic processes upon an audience subjected to the runaway logic of obsession, with only the painful distance of absurdity as guarantee of sanity. It is at MGM that Avery joins such live-action directors as Bunuel, Rossellini, Fuller, and Godard in the elaboration of a modernist film vocabulary, disjointing narrative linearity, isolating libidinal forces, dislocating sound and image, piling up the excesses of multi-layered contradiction, de-normalizing the whole process of linkage articulating the absurdities of Our Daily Lives.

Two developments, the breathless acceleration of the gags and a new control of extremes, [1] both made possible by an increased flexibility in character design and animation technique, marked Avery’s work with his new unit at MGM (including such veteran animators as Ray Abrams, Irv Spence, Preston Blair, and Ed Love), allowing him to explore areas only hinted at in the Warners films (although Warners itself was to undergo a parallel development in animation style and technique at about the same time). The speeding up of the pace not only altered the relationship of the audience to the cartoon but also allowed Avery to experiment with new narrative structures more dependent upon complex rhythmic forces than plays with given formats. The emphasis on the extremes underscored dialectic of process, the stop-and-go rejection of alternatives implicit in the very violence of the one “chosen.” The impact of Avery’s extremes is perhaps most visible in his celebrated “takes” – bodies that break apart like a mad contradictory gaggle of exclamation points or zip out limb by limb, jaws that drop open to the floor in shock, necks that sprout multiple hydra-heads of surprise, tongues that jaggedly vibrate in horror or infinitely expand in desperation, eyes that grow the size of millstones or spring out of their sockets or multiply to form sets popping out in rows toward their object of lust or terror.

Avery’s “extreme” animation, with its jolting juxtapositions and violent fragmentation, is very different not only from the “natural continuous order things” of a Disney cartoon, but also from the unconscious dream flow of what Greg Ford calls the “mindscape” of a Clampett cartoon. Rather than defiantly flaunting taboo in the exuberant ego defiance of the adolescent, for whom anything is madly, wonderfully, and unthinkingly possible (Clampett), Avery’s films like those of Bunuel, present every form of madness with hallucinatory clarity and analytic distance, tracing the absurd and tragic forces of repression and the full scale marine-landing return of the repressed, and exposing in the process the logic of that ganglion of enforced obsessive compulsions labelled “normal behaviour.”

Yet there seems to be little in the Avery MGM cartoons that is not already, present in the Warners cartoons – but now sped up, pushed to excess, and very differently structured. A comparison between Avery’s Bugs Bunny series at Warners and Screwy Squirrel series at MGM is a case in point. The Bugs Bunnys were part of a hunting format Avery developed at Warners, structured around the mind games perpetrated on a dumb hunter by his vastly intellectually superior prey. (Avery had an undying love for not-so-bright characters, often giving them his own “duh” voice.) The beautifully balanced exchange between the amused, highly conscious “underdog,” constantly, effortlessly, and artistically reversing the situation, and genuinely grateful to his pursuer for the never-fail fall guy setups (witness the soon-to-be-classic smacking kisses Bugs bestows on Elmer in A Wild Hare [1940), the first true BB cartoon) and the stuck-in-his-role-playing hunter, so programmed that nothing passes through his brain and totally devoid of all sense of proportion or humour, was to lay the groundwork for countless late smart-aleck/dumb patsy Warners cartoon showdowns.

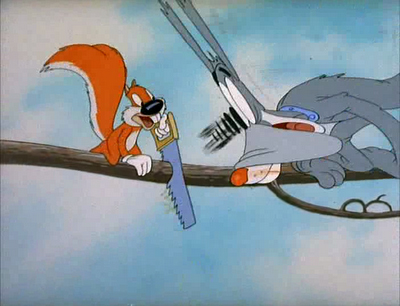

Avery himself was to cast various characters in these roles, but in Bugs and Bugs alone was Avery to create a character whose grace and charm were a gift to audience identification, whose energy could animate action, whose delight could spin gags. To a certain extent Screwy Squirrel was Avery’s MGM equivalent to a mischievous table-turning huntee. But where Avery’s Bugs Bunny cartoons have a lyrical contemplative beauty (compare Bug’s oft-repeated, traced, and re-traced mock death scene, graceful pirouettes, and supple carrot-feeling fingers in A Wild Hare), the Screwy Squirrels are rapid-fire cacophonic assaults on the audience. For Screwy, true to his name, is truly and certifiably insane, nutso, bonkers. His escape from the asylum in Happy-Go-Nutty (1944) is ample proof: sawing through the bars of an open cell door, he then compulsively climbs over a wide-open gate.

Heckling Hare (1941) features an extended falling sequence ending with the formerly terror-maddened duo Bugs Bunny and dumb dog matter-of-factly slapping on the brakes and screeching to a halt inches from the ground – fooled ya’. In Happy-Go-Nutty, when the dog is precipitated over a cliff by Screwy, the squirrel is waiting for him at the bottom, hawking an “extra” headlined “Dumb Dog Falls for Corny Old Gag” with a feature photo of the dog going over. The obvious exaggeration of the Heckling Hare fall and the reaction to it and the suddenly gained character and motor control at the end bespeak a joy in the possibilities of the situation exploited to the hilt by the characters as actors playing to and with an audience. The Screwy Squirrel gag, on the other hand, like so many of Avery’s meta-gags, calls into question the provenance of the image, the whole relationship between an event and its recording, creating a stupefaction in the somehow duped audience not synonymous with its very real pleasure in the excellence and daring of the joke, and divorced from any surrogate figure to incarnate that pleasure. The speed of the gags in the Screwy cartoons is such as to astonish, bewilder, and generally disorient the audience, left far behind in the wake of the manic madcap.

Whereas Bugs constantly defines the spirit and source of humour, shared with the audience and directed at some form of blindness, Screwy can refer only to the mad cartoonist in the sky: in Happy-Go-Nutty the characters rush into a very dark cave, sounds of crashing objects, and Screwy lights a match to tell the audience, “Sure was a great gag. Too bad you couldn’t see it.” While Warners, particularly in the brilliant films of Chuck Jones, was to develop Avery’s Bugs and Daffy until their personalities could encompass, control, and structure all levels of action and meaning, Avery’s characters at MGM become more and more visceral representations of abstract social and psychic forces beyond personality control.

Sign Language

In Happy-Go-Nutty the dog bags Screwy only to find another Screwy in front, him. Disgusted, he dumps the first Screwy out, picks up the second, and throws him in a bin marked For Extra Squirrels. The blatancy of the labelled garbage can, expressly there for the avowed absurdity of the gag, contrasts strangely with cartoon’s usual inventive and unexpected use of available props or sudden intrusion of incongruous elements, allowing the audience no illusion of vicarious fantasy control over the image, which begins increasingly to write its own logic. Indeed, Happy-Go-Nutty is full of insolent objects, as solid and realistically drawn as they are alien to the landscape: an anvil outside the nuthouse walls, whose only purpose seems to be as a surface for Screwy to compulsively bang his head against; ringing telephone in the middle of nowhere as setup for a vaudeville gag; a Coke vending machine to afford the pause that refreshes to hunter and hunted who drink, say a burp apiece, and continue. In The Cat That Hated People (1948) a cat on the moon is subjected to the surrealist logic of inexorable functionality as pairs of synthetically made-for-each-other objects (a scissors and a piece of paper, a tyre and a nail, a lipstick and a giggling pair of lips) chase each other across the lunar landscape, playing out the Marxist nightmare of alienation. Together with the breakneck pace, the insistent physicality of objects enabled Avery to work out wildly elaborate violations of the time-space sense. Droopy’s Good Deed (1951) features such a variation on a classic Avery paranoiac meta-gag: a good-for-nothing bulldog, in a murderous attempt to defeat Droopy, becomes the best Boy Scout, and meets the president(!), disguises himself as a woman, and stuffs several sticks of dynamite into a purse he ostentatiously drops in front of Droopy. He then jumps onto a cow, which gallops to an airplane, which speeds alongside a taxi, which instantly transports him to a building, the entire trip occurring in a matter of seconds, the vehicles becoming larger and larger in the frame, more and more instantaneous in their trajectory. But he has no sooner shut the door to his apartment, panting in exhaustion, than there is a knock at the door and there stands Droopy, who politely explains, “You dropped your purse ma’am,” hands it to him, and departs, leaving the bulldog to gape in stupefaction at the purse, which then explodes in his face. But the real object lesson comes in Bad Luck Blackie (1949) in which a sadistic bulldog gets his comeuppance in the terrifying forms of larger and larger objects that materialise from nowhere to fall on the luckless beast. In the awesome overkill finale a kitchen sink, a bathtub, a piano, a steamroller, an airplane, a bus, and an ocean liner thud from the sky, one after another, one behind the other, pursuing the dog toward the receding horizon, like victims of some avenging God-made disaster.

The new drawing style at MGM made possible many such plays with varying forms of representation. But, increasingly, the cartoon image began to reflect a world composed of images, the representation of a world perceived through a barrage of multiple and conflicting forms of representation. Blitz Wolf (1942), the first and one of the greatest of the Avery MGMers, casts the Disney Three Little Pigs in the role of defenders of a Free Pigmania, their old arch-enemy, the Big Bad Wolf, is fittingly slotted into the role of Hitler. Blitz Wolf is more than a film about the war, it is a film about the perception of the war back on the home front, a perception formed through representations, images, and words divorced from their unimaginable context. Thus everything is labelled and word-associatively activated: a scream bomb that screams; an incendiary bomb that gives Hitler a hotfoot; Hitler’s tank, inscribed Der Fewer Der Better, and subtitled German dialogue; shells explode to form the words BOOM or WHOOSH; a labelled Tokyo sinks, rising sun and all, in a single frame to leave a boasting sign: Doolittle Dood It. Wild and wacky analogies measure both their distance from reality and their closeness to some inverted survival sanity: a Mechanized Huffer and Puffer blows the first pig’s house down, leaving only a sign: Gone with the Wind, and another sign with an arrow sprouts up to comment, “Corny Gag, Ain’t It?”; a screaming shell is halted inches from its target by a copy of Esquire held up by Sergeant Pig; the shell retreats and returns with several of its whistling buddies, who then fall over in a dead swoon.

Narrative Frame-ups

Signs and labels of all description are but a part of the multi-layered text that is an Avery cartoon, fragmenting the context, emphasising the process of the gags, underscoring the director-audience complicity in awareness of the cartooniness of the cartoon. Live-action footage, magazine-ad drawings, and contrasts in proportion, texture, and drawing style were also extensively used by Avery. But unlike the disruptive use of such devices at Warners (as early as 1938 Daffy, in Daffy Duck in Hollywood, slaps together an amazing montage of live-action stock footage), at MGM these incongruities became the very stuff of the film, no longer disrupting a given format but creating its own. The incredible speed of the gags and the wide spectrum of representational styles allowed Avery to create totally new narrative structures, able to contain the most divergent shifts in texture and tone. While some cartoons (like the magnificently structured Bad Luck Blackie, considered by many to be Avery’s masterpiece) perfectly orchestrate these divergences in a complex equilibrium of tensions within a more classical narrative framework, others seem to take off in all directions at once, held together by some self-generating centrifugal force.

Take, for instance, The Shooting of Dan McGoo (1945). The cartoon casts three Avery regulars, the Wolf and the sexy redheaded beauty of the fairy tales (see below) as villain and “gal named Lou,” respectively, and Droopy, the sadsack basset hound, as hero, although, as in all the Droopy-Wolf cartoons, the Wolf steals the show with context-mastering lines like “What corny dialogue!” and wild and wolfy reactions to Red’s explosive Preston Blair-animated number “Oh Wolfie.” Lou’s number (an incredibly sexy multiservice salute to our fighting boys out there), the Wolf’s braying and howling reactions, and Droopy’s unemotional wet-blanketing of the Wolf’s overheated “takes” (rolling up and neatly tucking in the Wolf’s length-of-the-table extended tongue, holding up a menu to block the latter’s vision, through which the Wolf’s eyes immediately burn two charred holes) form the core of the cartoon, while around it local colour runs riot in fifty directions, each gag taking on a rhythm, visual style, and context all its own and, in its very separation, interreacting violently with everything around it. The camera pans past a bartender strategically stationed in front of a typical saloon cheese-cake painting of a supine woman, only her head, shoulders, and legs visible, and returns for a better look. The bartender, crossing his arms, advises, “You might as well move on, I don’t budge from here all through the picture.” In the later free-for-all gun battle he does move, only to reveal a sign lamenting “I ain’t got no body” where the rest of her should be. Whole gamuts of disparate graphic styles are incorporated into a single sequence: the Wolf orders a drink, cut to a close-up insert of gag-labelled bottles (4 Noses, with appropriate proboscis cluster); and when he drinks, pan to an Alka-Seltzer cutaway diagram of his stomach, where the drink as a rebounding fireball sends the whole Wolf, now totally transformed into an abstract fiery comet, ricocheting around the ceiling beams; in the midst of a verbal altercation, the Wolf suddenly menaces Droopy with an enormous ten-foot penknife that materialises from thin air, its mock-phallic resonance underscored by the hot fanfare opening of Lou’s act, which interrupts the action. The very air abounds in incongruities, including wild disparities in the level of gags: immediately following a particularly gruesome-grotesque introduction to the town (a sign reading Double Header Today – pan to two gallows with nooses, then pan further to a smaller gallows with sign: Kids 15¢), comes a typical Avery “funny-you-should-think-it’s-funny” joke as anticlimactic mirror of the first: saloon doors over which a sign reads Beer and a pan to the right for a miniature set of matching doors labelled Short Beer.

Whatever narrative unity is provided by the voice-over intoning of Robert Service’s overblown Yukon saga, of which the cartoon is supposedly an enactment, is undercut constantly by overliteralizations of the text (at the words “the drinks are on the house” everyone rushes out of the saloon to down a libation on the roof — on the house, get it?) or mock-fidelity to the plot (the “dramatic conclusion” unfolds in about three seconds, ridiculously and matter-of-factly sped up to be on cue with the text). Between the calling-the-shots narrator and Droopy’s “explanatory” asides to the audience (along the disorienting lines of “Hello, you happy taxpayers”), which are more alienating than complicity-inducing or action-forwarding, the whole narrative races to its pre-written conclusion, cycloning along in its wake entire worlds of don’t-quite-fit-in associations, in a perfectly controlled rhythmic chaos that only Avery could conceive and only Avery could execute.

Droopy

Droopy, Avery’s nearest approximation to a “star” at MGM, a kind of ambulatory non-identification principle, quite similar in that respect to Egghead, but unlike Egghead, an embodiment of a moral heroic code, was featured in most of Avery’s later genre pics, mainly Westerns. Unlike the Warners costumers, structured around the multiform reactions of Bugs and Daffy to their eagerly assumed (Daffy) or philosophically accepted (Bugs) roles, Droopy is plopped down in a situation he neither fits nor interacts with, passively following the rules, while all attempts to defeat him backfire by the laws of that Divine Providence that always (if arbitrarily) protects the “good.” A continual graphic and verbal understatement, he is set against a wonderfully overstated villain, the Wolf, who plays his part with all the orchestrated panache of a seasoned scene-stealing character actor. Droopy is usually cast as sheepherder or homesteader interloper, dogged, unconscious domesticating force of civilization (Droopy and his flock of sheep inexorably mowing a vast swath of locust-devastation through the Texas landscape of Drag-Along Droopy [1954]) against the I-took-this-land-from-the-Indians-so-don’t-nobody-fence-me-in cattleman Wolf (taking off his hat reverently to his trusty gun, reluctantly shot to take it out of its wounded yelping misery, and intoning his oft-repeated credo, “It’s the lawh a’ the West,” or gleefully chortling as he pumps a cow full of air until it floats gigantic and balloon-distended above the barn in Homesteader Droopy [1954]). Droopy was also featured in a series of rivalry cartoons between 1949 and 1952, usually against a try-anything, bag-of-dirty-tricks bull-dog named Spike. Although brilliantly animated, these situational duels (involving circus feats, Olympic games, bullfighting, and so forth) number among Avery’s weaker efforts, the quid-pro-quo structure lending itself to more personality-directed animation, the enforced symmetry of the conception resisting Avery’s more manic narrative build-up.

But Droopy perhaps worked best as foil to the Wolf’s subjectivity in Avery’s paranoia masterpieces, Dumb Hounded (1943) and Northwest Hounded Police (1946), where his inexplicable omnipresence perfectly embodies the inevitable futility of any endeavour at psychic breakout from obsession and the impersonal forces of understated repression lurking under every unturned stone. In Northwest Hounded Police, everywhere an escaped-convict Wolf goes in his increasingly desperate flight (in a nest atop a virtually unsealable promontory, underwater, behind fifteen locked multi-coloured and -form doors, on a deserted three-foot island), he finds Droopy already in occupancy (within an egg in the nest, in a school of passing fish, under a pebble-sized rock), finally reaching Dostoievskian proportions: the Wolf, attempting to get a new face from a plastic surgeon, has the bandages removed and gazes upon his new face in the proffered mirror – Droopy’s. The Wolf’s extreme reactions (a compendium of Avery’s most memorable takes) paint a vivid picture of the violence of his realisation that there is no escape (many of Avery’s films portray imprisonment of one kind or another). The entire film has the logic of the unconscious: the Wolf’s escape has the ease of a cartoon dream (he escapes by penciling in a door, then goes by the warden’s office all the way around the door frame – gravity inoperative), and his pursuit all the mounting relentless illogic of nightmare, until even the cartoon-reality gags share in the madness: the Wolf flees into a movie theatre only to see Droopy follow the MGM cartoon credits on screen. Yet it is also the logic of the fanaticism of the Mounties (“We aim to police” over their headquarters). The last shot of the cartoon is a revelation of both rampant paranoia and its very real basis (in a stacked deck of 1000-to-1 odds): a corridor of multiple Droopys stretching to infinity. Avery perfectly understood the terrible impersonality of the heroic principle backed and justified by limitless forces of repression.

“Oh, Wolfie!”

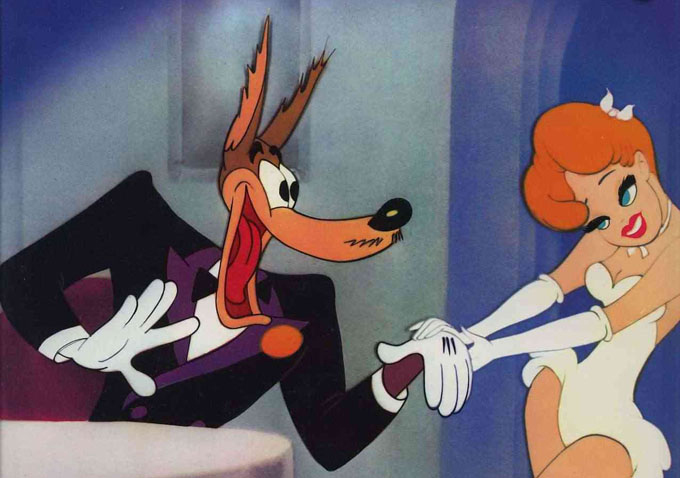

If Avery declined to create heroes with whom his audience could identify, the Wolf could be rather cornily said to represent “the animal in all of us,” with a relish and visual pizzazz few audiences, alas, can equal, unequipped as they are with yo-yo eyes and regenerative limbs. For in all the Wolf/Red films, the Wolf is, above all, an audience. Sex enters Avery’s MGM films as a reciprocal act, a duo between performer and audience, a perpetual cycle of temptation and frustration. At the same time it is a double act: the Wolf’s feverish takes (magnificently conscious choreographed celebrations of the wild and wondrous id) supplying perfect counterpoint to Red’s smooth and silky come-ons. Thus Red, as Little Eva (Uncle Tom’s Cabana [1947]), suggestively demure in a low-cut Southern belle ball gown with matching parasol, yearns with velvet voice for someone to carry her back to Ole Virginny, while Simon Legree (a barely human version of the Wolf), all controls spinning madly, compulsively and blindly runs the gamut of time-honored sex substitutes: in his sexual insanity, Legree unwittingly smokes his own nose, stubbing it out in an ashtray, “celeries” the saltcellar and munches on it (his teeth dropping out into a convenient butter dish), slices himself a wedge of table and chomps away, butters his hands and devours them up to the elbow, and gallops off with the middle chunk of a stage-prop Colonial pillar in his arms, instead of the red-haired plantation belle, Little Eva.

To what extent it is all an act, extending beyond and through the characters, a series of movie-imitative roles the characters eagerly, if naively, assume to disguise their rural origins and create a social persona to impress each other and themselves, can be measured by the rapid metamorphoses these characters can undergo: in Red Hot Riding Hood (1943), Avery’s first MGM foray to grandma’s house, Red’s torchy rendition of “Daddy I Want a Diamond Ring” encompasses within the continuum of sheer provocativeness an amazing variety of tones, simultaneously funny and sexy, from a raucous “Hey Paw” to an imperious “Fahther” to a mock childish-awkward knock-kneed “Daaaddy.” In the téte-à-téte that follows Red’s number the Wolf shifts from crude familiarity when talking about Red’s grandmother (“forget the old bag”) to suave French-accented persuasion (“Come with me to zee Casbah”), to hillbilly guffaw (“What’s yer answer to that, babe?”) with lightning speed, while Red caps her refined-affected Katharine Hepburn disclaimers with a bellowed “No” loud enough to knock the Wolf clear across the room.

But it is above all as a force that sex invades Avery’s cartoons, a blind energy oblivious to all physical laws – until it rushes headlong into intersubjectivity, in the form of conflicting desire or active repression. The aggressor, hot on the trail of the sexual object, suddenly finds himself the object of another’s sexual aggression: the Wolf no sooner embarks on his pursuit of Red (Red Hot Riding Hood) than he encounters her overlibidinous grandmother or (in Swingshift Cinderella [1945]) her martini-swigging fairy godmother – and the chase is on. It is this sexual drive that structures the films, from the frenzied stasis of act/audience cross-cutting (more complex in cartoons like Swingshift Cinderella, The Shooting of Dan McGoo, and Little Rural Riding Hood [1949], where a “third,” repressive element constantly intrudes, with mallet, baseball bat, or ball and chain, in repeated attempts to squelch the Wolf’s undying lust) to the express-train propulsion of the steeplechase pursuit. The nonstop rhythm (the Wolf and fairy godmother whizzing around the walls in Swingshift Cinderella or through a dizzying and constantly displaced series of trapdoors in Little Rural Riding Hood) slackens somewhat (the Wolf flings open a door and dashes into the brick wall it opens out on, the camera holding on the sign affixed to the bricks: Imagine that, no door!) or screeches to a halt for a momentary pause (the Wolf lovingly contemplating the hatpin he is about to jab into grandmother’s temptingly presented posterior), only to take off again with renewed vigour.

Nor is the sexual drive isolated: sexual teasers crop up continually in Avery’s films to further or divert other obsessive drives. Uncle Tom’s Cabana throws a new twist into the sex-money nexus: Simon Legree, absconding with the cash register under his coat, catches sight of Little Eva and rings up a whopping erection, the cash drawer suddenly springing from his pelvis. Nor is the sexual structure always explicit: Uncle Tom, prevented by age, race, and Harriet Beecher Stowe from having other than paternalistic interest in Little Eva, voice-over narrates himself into rather ambiguous sexual relation to Simon Legree – cast alternately as Superman (repelling machine-gun bullets with his ill-fitting costume) and victim of escalating Legree-propelled forces (camels, elephants, battleships, and steamrollers), sometimes even in situations generally reserved for the damsel in distress (tied to a floating log about to pass through a whirring saw, lashed to railroad tracks), until, in the phallic finale, he tosses the Umpire State building with Simon Legree on top over the moon.

The Nature of Force and the Force of Nature

Sex is not the only drive that structures Avery’s cartoons. In King-Sized Canary (1947), what starts as a scrawny alley cat’s desperate ransacking search for food (in a comfortable, if foodless, suburban household) rapidly escalates, with the help of a little bottle of Jumbo Gro, into a runaway power struggle, as first a canary, then a cat, then a dog, and then a mouse drink and grow to larger and larger proportions, the suburban-dwelling canary and dog quickly dropping out of the action as the initial survival impetus reasserts itself. The enormous distended bodies of the characters, with their tiny heads and hands and giant swollen bellies, give a peculiar edge to the inexorable Hegelian duality of postwar realpolitik that destroys the initial class solidarity between suburbia-excluded lower-class cat and mouse (mouse to cat: “You can’t eat me – I seen this picture before, and before it’s over I save your life”). This solidarity is at least momentarily regained as the cartoon ends when the gargantuan cat and mouse, barely able to straddle the much smaller globe of Earth, arms around each other, wave to the audience, having explained “Ladies and Gentlemen, we’re going to have to end this picture. We just ran out of the stuff.”

If many Avery cartoons follow the manic rhythm of mounting obsessive forces (the brilliantly animated Slap-Happy Lion [1947] equalling Northwest Hounded Police in that respect), many, like Lucky Ducky (1948) and Half-Pint Pygmy (1948), possess a curious contemplative beauty, even within as linear a structure as the chase, as they trace the process of that other great force – nature. Lucky Ducky follows with detached fascination the extended pursuit by a duo of hunters in a boat (George, short and irascible, and Junior, large and very dumb, two Avery regulars) of a small new-hatched duck with the face of an ingenue (coyly stripteasing out of its shell), the mechanical staccato laugh of a toy devil, and the superhuman strength (picking up the large boat as if it were a feather and batting it all over the horizon) of a force of nature, which indeed he is (the cartoon ends with the integration of this newest member into the indigenous community of ducks as they conga-line their defiant ring around the after-hunting-hours impotent hunters). Unlike the manic cartoons, which create a paranoid homogeneity through extreme subjectivity (everything is part of the same nightmare), the contemplative cartoons, through a total lack of structuring subjective consciousness, create a phenomenological homogeneity where everything in the frame, be it anthropomorphic, mechanical, or natural, is an interchangeable part of the same impersonal process: Junior starts the boat by absent-mindedly wrapping the starter cord around George’s head and pulling, which whirls George’s head around and somehow makes ignition contact simultaneously; the duck confronts George’s rifle with an African mask, whereby the rifle screams horribly, tongue protruding, and shrinks to the size of a toy, disgorging its bullets; a mother tree snatches its baby from the path of the oncoming boat in a Disney-like shot that is held for a disconcertingly un-Disneyish length of time in a long, calm, empty aftermath of action.

The shattering of the illusion of control (over oneself, others, or nature), which almost all Avery’s films are about, creates less anxiety in the nature films (probably because it carries no subjective weight at all) than a vague feeling of malaise, mitigated by an enjoyment of the free play of totally unhierarchical, unsubjective forms. A long lyrical sequence traces the progress of a coconut launched by a pygmy George and Junior are chasing in Half-Pint Pygmy. The cannonball coconut first knocks out George, then Junior, lands on a zebra whose stripes fall like steel bands, strikes an ostrich, causing his head in the sand to pop out of a further hole, flies into one kangaroo’s pouch and out another’s, makes a leopard’s spots drop like poker chips, knocks a turtle out of its shell, bonks a giraffe on the noggin, causing his neck to contract while that of an adjacent hippo expands, squelches a long-legged crane, flies over two goalposts to loud cheers, shatters a rhino’s armour plate to expose a dessicated body underneath, inverts the humps on a camel, and finally backfires to lay out the pygmy who started the whole thing.

Animation of Tomorrow

In the 1950s, as the animation became more limited, the drawing style more streamlined, and the perspective flattened out, Avery’s cartoons began to be more formally structured around spatial ideas already operative in his earlier films. There are myriad magical gags concerning a mysterious third dimension that opens somewhere within the very two-dimensional surface, so that a train can disappear into a house and reappear coming out of a nearby barn, a moose can run into a barn, the barn door can be folded up very small and tossed aside, whereupon it unfolds into a trapdoor and out charges the moose (Homesteader Droopy). Rock-a-Bye Bear (1952) and Deputy Droopy (1955, co-directed with Michael Lah, Avery’s major animator in the 1950s) are foreground/background exercises in spatial compulsion, as characters, working in a space where they cannot make a noise and continually besieged and goaded to utterance, must rush themselves or (when bodily trapped) each other’s disembodied heads or screams-in-a-bottle to a neighbouring knoll, there to give voice to their pain. Flea Circus (1954) explores the relationship of long shot to close-up in tracing the stage and private lives of a company of performing fleas.

Within a revised spot-gag structure, TV of Tomorrow (1953) uses a frame-within-a-frame setup to depict the take-over of the suburban household by a small box and the reciprocal smaller-than-life domestication of the image. The jarring implications of television’s insidious replacement of direct experience and total integration of technology into the home are highlighted in a contract bridge set featuring a live-action black-and-white TV “fourth,” who deals cards directly from the screen to an animated, colourful card-playing threesome in a brilliantly drawn and coordinated sequence. But the confusion of inner and outer, of the unlimited fantasy power of the image and the packaged enclosure of the box-as-possession (an age-old sexual problem given new impetus by the overweening voyeurism of sex through technology) is most explicit in Avery’s lineup of boob tubes, including a keyhole-shaped set for peeping toms, a slot-machine model “for those who like to-gamble on their channel,” which rolls first the beautiful head and arms, then the lovely legs of a woman, only to tum up a lemon in the centre, and a new low of displaced sexual drive: a TV set with a deeply plunging, lace-trimmed neckline.

More formal narrative structures began to succeed the more associative, all-inclusive, textually richer films of the 1940s, abstracting still further the drives and compulsions of the characters, themselves more one-dimensional, as the 1950s nightmare of dehumanising mechanisation, embodied in the movements of limited animation, invaded the screen. Avery inaugurated a whole series of cartoons at MGM structured around single, non-narrative repetition-compulsion situations. In Billy Boy (1954) the goat of the title eats everything in sight and, rocketed to the moon in a desperate attempt to end its ravaging destruction, eats that too; the film ends before we can discover what’s next on the menu. Cock-a-Doodle Dog (1951), one of Avery’s many cartoons about induced insomnia, is the sad tale of a sleep-craving bulldog haunted by a scrawny, half-dead rooster, who is driven by some obscure ineluctable need to crow over and over again, undaunted by all attempts to silence or murder him, like some recurring nightmare, and a horrible, neck-wringing rasping mechanical screech it is. The cartoon ends with the bulldog, now completely insane, crowing compulsively. Madness is also the fate of the little bongo player, Mr. Twiddle, nerves frayed to a frazzle by raucous music, who seeks silence at Hush-Hush Lodge in Sh-h-h-h (1955), Avery’s last cartoon, but meets instead the steady inexorable sound of a wah-wah trombone and a woman giggling inanely in an otherwise totally silent void.

As Avery moved toward more limited animation, his cartoons began to reflect the knee-jerk reflexes of the bourgeoisie, the relatively innocent movie-imitation role-playing of the basically lower-class characters of the fairy tales giving way to the empty mechanisms of socially determined compulsions (as the scrawny alley cats of the 1940s give way to the back-stabbing, get-to-the-top bulldogs of the 1950s). Clothes make the man in Magical Maestro (1952), where at each flick of an avenging magician’s wand an opera singer flashes without warning from one outlandish costume to another, with vocal accompaniment, gestures, and miscellaneous materialising rabbits to match, from tuxedoed high opera to skipping sailor-suited little boy to tutued ballerina to fruit-saladed Carmen Miranda. Cell-bound (1955) explores the dilemma of an escaping convict trapped in the warden’s television set and forced to play all the roles on all the channels. The frantic activity of the convict (portraying hero, villain, and girl in a Western, knocking himself out in a prizefight, playing all the instruments in a dixieland band and, finally, acting out his own insanity) contrasts chillingly with the very limited animation of the warden, whose occasional departures from wound-up automaton are switched off suddenly to return to dour normality. The Crazy Mixed-Up Pup (1955), perhaps the most imaginative of the four films Avery directed at the end of his career for Universal, exploits limited animation to emphasise and reinterpret the cartoon’s tendency to de-humanise the human and humanise the de-human. A cross-eyed mix-up with blood plasma causes a reversal of the master/slave dialectic worthy of Bunuel, contrasting the vitality of the hip lower classes with the push-button mentality of the square, flag-sprouting bourgeoisie. The humdrum, paper/slippers routine of lifeless middle-class suburbia is laid bare by two complexly interwoven simultaneous intrusions: the sudden anthropomorphism of the pet dog who comes on with the suave sexual assurance of a Humphrey Bogart on this sterile “Father Knows Best” set; and the out-of-control mechanisms of long-repressed animal instincts in suddenly dog-ized people.

It is somewhat ironic that the one full-animation director who could brilliantly redefine his praxis to fit the possibilities of limited animation (already experimenting in the form in 1951 in the hilarious literalisations of idioms of Symphony in Slang before it became the order of the day by the mid-1950s) should choose, despite continued offers, to continue in the medium only in the limited form of TV commercials, although Avery’s Raid commercials are masterpieces of the genre and have had no small influence on commercial animation.

Epilogue

It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that Avery’s was probably the greatest post-Disney influence on studio cartoons. In the fertile cross-pollination of animation, where what one director innovated, another incorporated and transformed in an endless creative cycle, it is often difficult to pinpoint influence. Yet Avery’s effect on the cartoon was all-pervasive, accelerating the pace (the difference between pre- and post-Avery timing is extraordinary), enlarging the cartoon vocabulary (giving more scope and heterogeneity to the levels of gags), and emphasising the importance of more visible extremes, to name only the most obvious. Myriad Avery gags and narrative structures reappear time and time again in others’ cartoons: Avery’s magnificent takes were incorporated with varying levels of success into an incredible diversity of cartoon characters and animation styles. Avery’s contribution to animation is inestimable, his 130-odd films, many of them among the greatest cartoons ever made, brought to the cartoon and to its audience an analytic consciousness matched only by an accompanying mad, free-associative liberation of the unconscious, the aspiration of the Surrealists that so few of them could realise. An Avery cartoon is a series of shocks: the reversal of patterned expectations, revealing the possibility of change and the forces that resist it; the creation of new connections and the destruction of the physical, moral, and psychological iron links between cause and effect; the redefinition of psychological time and space; nongags, exposing the gag itself as a form of compulsion; meta-gags, bringing the process of production into the cartoon. Avery’s cartoons stretched the possibilities of the medium so far that, although few followed him all the way, the cartoon was just never the same again.

Endnotes:

[1] Disney was the first to divide the work of animation into “extremes,” drawings of poses or attitudes of the characters, to be executed by the animators, and “in-between,” the intermediary drawings of the movements leading from one extreme to the other, to be executed, not very surprisingly, by the in-betweeners. This distinction is a very hairy one, because the division into extremes and the division of labour vary greatly according to animator, director, studio, and individual cartoon. Disney’s animation style tended to erase any visual distinction between drawings, giving the illusion of a smooth continuous movement. Avery and Jones, on the other hand, tended to emphasise extremes and make them stand out sharply, introducing a radical discontinuity in the visible process of production and allowing the audience to experience movement and change as an open process rather than as an irreversible organic becoming.