Everybody says that digital video allows you to do this or that, without even saying what was actually done. Digital video allows you to be free, but free to do what? [1]

This special dossier comes after our Late Godard: Digital + 3D Cinema research symposium held 21-22 October 2015, at the University of Technology Sydney. This brought together scholarly and practice-based academics, contemporary artists and film critics to discuss the new forms and aesthetics that have emerged in relation to Jean-Luc Godard’s late digital films Film Socialisme (Film Socialism, 2010), Les trois désastres (The Three Disasters, 2013) and Adieu au langage (Goodbye to Language, 2014). The morning session commenced with a keynote address by Miriam Ross which looked at Adieu au langage within the wider history of stereoscopic cinema. The afternoon panel session, “Digital Godard: Forms and Aesthetics” hosted by ABC film critic Jason Di Rosso and featuring Julian Murphet (University of New South Wales), Dirk De Bruyn (Deakin University) and artist Alex Gawronski (Sydney College of the Arts), was broadcast on Radio National, and can be listened to online in both condensed and complete versions.

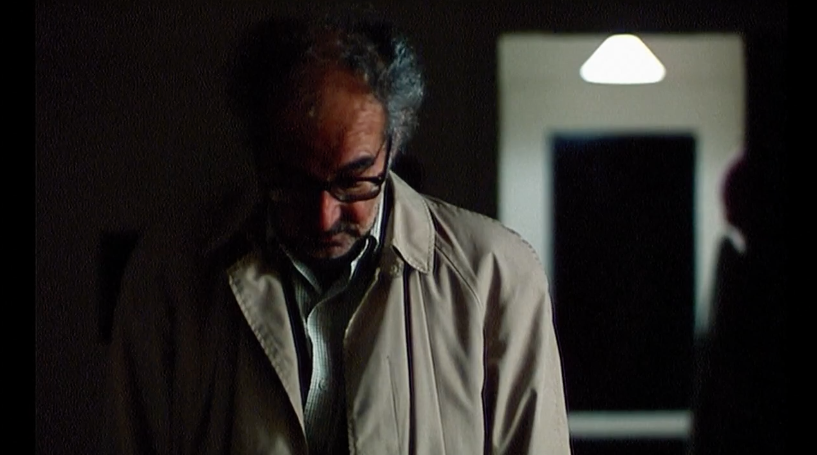

The symposium was motivated in part since Adieu au langage had not been screened in Sydney (it had its only Australian screening at Melbourne International Film Festival 2014), as well as in response to our interest in Godard’s late filmmaking techniques, which happen on the fringes of an industrial production model and use prosumer model digital technology in interesting ways to create images of startling beauty and depth. We were also interested in exploring Godard’s collaborative practices, so the symposium included screenings of one of Godard’s early shorts, Tous les garçons s’appellent Patrick (All the Boys are Called Patrick, 1957) made in collaboration with Éric Rohmer, and a film portrait of Godard made by his current collaborator Fabrice Aragno, Quod Erat Demonstrandum (2012).

The symposium raised stimulating ideas with respect to globalisation, stereoscopic media, screenwriting, micro-budget filmmaking and small scale, collaborative digital production processes. Working into his mid 80s, Godard shows ways to generate cinema from bare means and outside a traditional production model. As suggested by Miriam Ross, the way Godard uses 3D technology challenges the dominance of the highly controlled, big budget model of 3D cinema making, and demonstrates the possibilities for other low budget filmmakers. This is a welcome and motivating lesson in an Australian context. In addition, these late works raise new questions in relation to theories of the image as well as demonstrating a consolidation of interests that have run through his work since the beginning – experimental uses of technology, a deep relationship to painting, the use of found footage to explore ideas of politics and poetics, and an interest in spaces – natural, urban and global.

These four papers demonstrate divergent points of thinking in relation to Film Socialisme and Adieu au langage from four different zones of screen scholarship. Our aim in compiling these essays was to present a fresh perspective and to propose new spaces for engagement and ongoing discussion around the forms, aesthetics and significance of the work of Jean-Luc Godard today.

Thanks to our reviewers for this Special Dossier, the Editors of Screening the Past and in particular to Adrian Martin for his stewardship.

References

[1] Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Luc Godard: The Future(s) of Film, Three Interviews, 2000-01 (Bern: Verlag Gachnang & Springer, 2004).