Abstract:

In Michelangelo Antonio’s L’Eclisse (1962), Cold War Rome is conceived of as a sequence of controlling frames from which the camera seeks liberation. In the opening sequence a reversed picture frame vies with an electric fan in a modernist flat to convey the grueling endgame of a long-term love affair in terms of the conflict between traditional and contemporary art media. This paper examines the film’s contribution to an understanding of the emotional necessity behind contemporary art’s rejection of the past and the birth of new media in 1960s Italy.

It is widely recognized that Michelangelo Antonioni’s film L’Eclisse is a late Italian Neo-Realist critique of the alienating effects of capitalist reification, mass society, mechanization, dysfunctional gender roles and urban living in Cold War Rome. [1] In this paper I argue that part and parcel of this critique is the film’s attack on traditional art forms, particularly painting, though it is no less hostile to popular film narrative of the “Kiss-Kiss Bang-Bang” variety. [2] I want to explore the possibility that it is possible for films to express emotions about the history of entire media, that Antonioni did this in L’Eclisse and that to have done so engages with specific debates about the history of the death of painting in the international culture of the 1960s.

I begin with some thoughts on the respective origins of painting and cinema, which hinge on questions of religious art. Cinema’s attacks on the high status enjoyed by older media owe their origin to sacred rituals; Boris Groys was nevertheless persuaded that “cinematic iconoclasm operates less in relation to some religious or ideological struggle than it does in terms of the conflict between different media”. [3] In “Christ in His Beauty and Pain”, however, Gerhard Wolf speculates upon the possibility that the divergence of painting and film media stems from the optical regimes of two kinds of medieval art that claim their authority from direct imprints of the Godhead (acheiropoieta or icons “made without (human) hands”.) In Charles Peirce’s semiotic terms both Veronica cloths – the sudarium or sweat cloth that registered Christ’s features after Saint Veronica had offered it to him en route to Calvary – and the contents of icon covers – the salient features of sacred relics isolated for viewing by metal covers that occlude the rest – are indexical signs directly connected to their referents. While the indexical presence of both types of objects intensifies religious mystery, their modes of delivery offer alternative paths of development towards cinematic projection and framed picturing respectively. For whereas the Veronica cloth acts as a material screen transmitting the pure image of an absent divinity (a magical quality that film retains), the frame of the icon cover partially conceals the body of a sacred icon to concentrate its spiritual essence for the viewer, just as a frame accentuates the enclosed image of a painting. [4]

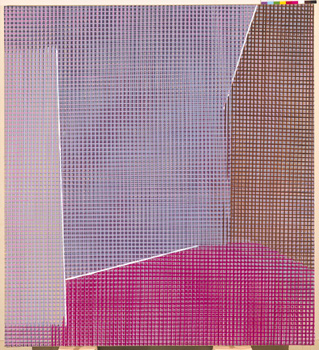

In relation to other aspects of both media, I contend that a continuity between painting and popular film narrative can be found if we turn to a later phase of art history: the invention of history painting in the Italian Renaissance and the intellectual drawing techniques that Vasari called disegno. According to Alberti, perspectival composition arranges bodies in space to tell praiseworthy stories (storie) through convincing suggestions of human movement. It is important to note that this conception of pictorial composition is alien to the storyless harmonies that enliven the flattened picture planes of modernist paintings. [5] The surface harmony of Soledad Sevilla’s abstract version of Diego Velàzquez’s Las Meninas, for example, flattens out the illusion of pictorial space on which the narrative elements of the celebrated original depends

Fig 1. Soledad Sevilla, Las Meninas no. IX, 1981-3, oil on canvas

Fig 2. Diego Velàzquez’s Las Meninas, 1656, oil on canvas

As the highest in the hierarchy of genres, history painting combines bodies in movement to narrate the heroic actions of virtuous souls. [6] It is significant here that the Italian word affetti means both motions and emotions, for in painting the one is needed to express the other. Anne Jensen Adams explains that:

Renaissance treatises on art advocate the use of body pose and gesture to express the internal emotional states associated with character. Gesture as discussed in these treatises has two functions. First, it conveys life, indirectly indicating the existence of the soul that animates the body. Second, specific gestures can be signs for particular emotions. Alberti wrote of how the “feelings are known from movements of the body.” Leonardo essayed in the same vein: “Let the postures of men and the parts of their bodies be so disposed that these display the intent of their minds”. [7]

Working in the Northern pictorial tradition, Rembrandt cogently developed this expression of inward emotions through external movement. As the second figure from the left in Rembrandt’s Syndics (1662) rises to answer the invisible speaker situated on our side of the picture surface, the interaction of bodies propelling narrative momentum includes our own. In Althusser’s sense we are “interpellated” by an open narrative fragment that forces us to comply with the assembled group’s authority. Our visceral responses to the representation of movement project our imagination into what will happen next. Mutatis mutandis, the void left by the next moment draws our narrative identification forwards. The relevance of such visual narrative techniques to film is suggested by Michael Tiern’s enterprising “how-to” book: Aristotle’s Poetics for Screenwriters: Storytelling Secrets from the Greatest Mind in Western Civilization. [8]

Fig 3. Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild, 1662, oil on canvas

Although the moving image repudiates the static space of painting to engulf the fictive space outside the screen (known as “hors-champ”), it takes from painting the capacity to tell stories by creating the illusion of bodies in movement. Filmic movement expresses emotion by putting figures and backgrounds in sympathetic motion with our kinetic sensations. It creates the illusion that the whole film, not just the figures, are alive and “going somewhere”. Jennifer Barker argues that:

a theory of cinematic experience that seeks to ground its analysis on the co-constitutive, reversible relationship between bodies: both those of the viewing subjects and also that of the film and its capacity for embodied perception and expression. Such an analogous relationship – one in which emotional sympathy’s “feeling for” is seen as derived from muscular empathy’s “feeling with” – between film and viewer “manifests itself in the muscular movements and comportments and gestures of each”. … Hence, watching a film involves a form of affective empathy: to understand a film is to grasp it “in our muscles and tendons as much as in our minds”. [9]

What happens, though, to the emotions associated with both media when, in a defining sequence of a film, the character physically interacts with a picture frame serving as the representative of another artistic medium?

Near the beginning of the opening sequence of L’Eclisse, Vittoria (Monica Vitti) distracts herself from the tension of breaking up with her lover Riccardo (Francisco Rabal) by engaging in a number of “typically feminine” household occupations. (Later she will clear the cups to the kitchen, make sure lights are out and curtains open and looks after her secretarial functions, for she also worked for him as a translator.) [10] After a night of gruelling argument she toys with a bourgeois picture frame with an overscale, imbricated leaf border. An expert on the history of picture frames assures me it is a fabricated prop that would overpower any image it enclosed. [11] Vittoria reaches her hand through it, extracts an ashtray full of butts left over from their quarrelling, centres the phallic bronze paperweight (a kitsch Henry Moore), and assesses the aesthetic effect of her arrangement. Pretty as a picture herself, she has composed a picture, just as the director has framed a film, but it does not hold her interest and we feel again the weight of her listless boredom. In the next shot we see her from the other side of the frame as she reaches over it to stroke the rim of a feminine vase whose shape was concealed by the frame in the frontal view. For all its triviality, this literal turning point subliminally determines our response to the rest of the film.

Fig 4. Picture frame in Michelangelo Antonioni, L’Eclisse, 1962, film still

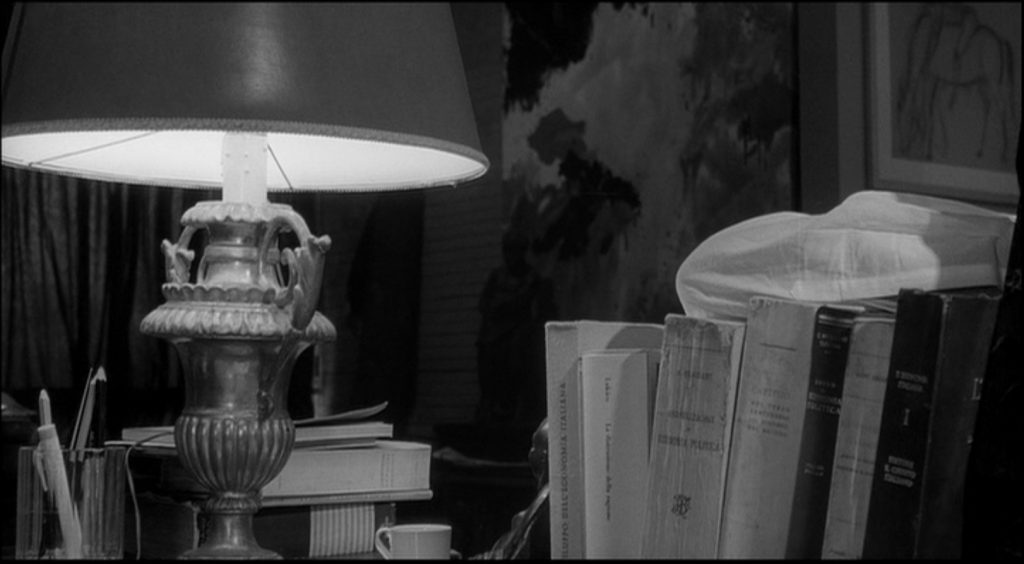

All this time Riccardo has been anxiously observing her from his chair, where his ardent gaze and forward inclination show how stirred he is by her distracted autoeroticism. His clenched first next to the onyx pyramid is a phallic symbol of thwarted Roman authority that answers the masculine shape of the stubby modernist sculpture she centred in the frame. The first shot of the film had been a natura morta, showing an arrangement of seemingly dead objects, including a white shape on top of some books. Only when the camera pans right do we realize it is Riccardo’s arm. It cues the theme of reification that Vittoria verbalizes later on: “What can I say? There are times when holding a needle and thread, or a book, or a man – it’s all the same”.

Fig 5. Opening shot: Riccardo’s elbow, Michelangelo Antonioni, L’Eclisse, 1962, film still

Her psychosexual decision to leave Riccardo is marked by the shot of the reversed picture frame. Her game with the frame was an attempt to distract herself from the anguish of the situation. She is carrying on as normal as she does with those other stereotypically feminine household chores. Riccardo does this too when he gets on with shaving. But the momentum of her dilemma continues through the unconscious fantasy that motivates her actions. The probing of the frame and centring of the bulbous sculpture is a tacit continuation of the sexual dimension of her affair with Riccardo, but the switch away from the paperweight represents her severance from him, the renunciation of sexual attraction and her transition to self-healing. Unknown to herself, her innermost thoughts are expressed through non-verbal play with symbolic objects, as in Kleinian child analysis. The corollary to her behaviour is that we too are unconscious of these matters on first viewing. We have no idea what is happening yet and will only understand on subsequent screenings. Its impact on us is subliminal. And yet, on a different level of understanding linked by this formal device, it establishes in the viewer a reflexive awareness of how filmic narrative operates in the rest of the film.

This aspect of the incident has attracted much attention. Apparently trivial as narrative incident, the prop says something thematic about the nature of film, and on the metacinematic level resonates with later key episodes. Vittoria’s manipulation of the picture frame, for example, anticipates her rotation of a crass novelty pen that dresses and undresses a nude woman in the parents’ apartment of her next, even less satisfactory lover, Piero (Alain Delon). [12] Another parallel is when she passes by a water barrel with Piero. She breaks a stick and sets it floating in the circular frame but separates it when it sticks to a sodden matchbook. It is another exercise in pictorial composition with similarly unconscious implications for her new relationship. The matchbook bears the funereal image of cypress trees and, like the previous picture frame, has mysteriously flipped over onto its other side when the water barrel recurs in the final sequence. [13]

The metacinematic meaning of the opening picture frame sequence is driven home by things flipping over throughout the film. Picture frames, bodies, soles of shoes, playing cards, pens, and sodden matchboxes all reverse themselves against the static background of pictorial cages that proliferate inside and outside buildings, trapping and releasing people across the city. This is a formal means of contaminating other scenes with the angst of the opening break up between Riccardo and Vittoria. Likewise, art frames fail to preserve their autonomy against the vulgar incursions of mass culture, which multiplies frames for its own purposes. Even the free expression of an abstract painting in Riccardo’s flat internalises a rigid intra-compositional frame. They belong to an interplay of doors, windows, curtains, mirrors, chair backs, partition walls, piazzas, road intersections, facades, passenger vehicles, shop window grills, and even spectacle frames. These and other frames, grids and containers rehearse a lexicon of cinematic modes derived from painting in which reversal, opacity, transparency, reflection, containment, compartmentalization and division are enlisted for a pastiche of static pictorial metaphors of interpersonal subjectivity and social power relations. Our awareness of frames overwhelms our attention to plot, yet strengthens the anomie of the existentialist drama played out by known and unknown characters.

Since the fabric of ancient Rome obtrudes in the film, there is surprising continuity between these cagings and the Early Modern discourse of urban framing to which Richard Trexler attributed that “rigidification and formalization of behaviour, called ritual, which signifies the presence of the holy” in Renaissance Florence. Yet to reinforce the alienating conditions of modernity cut off from an inscrutable past, the Holy in 1960s Rome is transformed into the menacing secular sublimity of nuclear war that threatens to obliterate all frames. [14] The frames of L’Eclisse stage rituals – domestic, economic, amorous – and the heightened awareness of existence that comes from breaking them.

This applies to the disruption of narrative in the opening sequence, where the lived geography of the flat and the story of the break-up are thoroughly scrambled. Antonioni ensures that we never gain our bearings. [15] If the modernist flat is a Corbusian “machine for living”, then the machine is broken. Antonioni breaks the 180 degree rule inside its interior, employs peculiar camera angles and confusing perspectives upon previously encountered scenes and perplexing mirrorings within a room cluttered with heterogeneous bric-a-brac. Freezing the story line, or leaving us to imagine it in the absence of logically unfolding events, arrests our conventional empathy, though we still feel the entropy of the couple’s declining intimacy in the boredom they exude. The sequence is felt as the culmination of a causal matrix whose sources neither the characters nor we understand but which resonates with “the abstract mimesis of lost emotions in the shape of … artefacts” from different times and places that congest the living room. [16] Each work expresses the emotions that went into its manufacture, which suck the characters’ emotions into their frozen voids, petrifying the characters’ bodies as if by contagion. When Vittoria walks out on him, Riccardo grasps a painting.

Despite the bewildering presentation, we infer what the broader problem is due to the characters’ dysfunctional relations, though what those are due to is the burden of the film’s meaning. Antonioni had declared that “Eros is sick.” [17] Broadly speaking the rift between contemporary science and fossilised moral habits brought about by the existential malaise of industrialised capitalism has corrupted gender relations by supressing emotional reality. Riccardo’s books and papers suggest he is a radical economist. She is in a subordinated gender role as his translator/secretary. Vittoria’s only recourse is futile attempts to escape from the multiple physical and emotional frames that encage her. As she opens the curtains, a phallic mushroom tower blocks Riccardo’s window. A phallic cactus impedes her exit through his front door. The horizontal, rectangular, modernist frame that surmounts the garden gate as she leaves the house is less an entrance statement for the flat as for the reified modernist world she re-enters. By the time she reaches the Borsa – the extraordinary Roman Stock exchange housed in Hadrian’s temple – it has turned into a frantic pressure cooker where economic modernity ferments inside an anachronistic cage. Escaping to the flat of a white Kenyan acquaintance prompts her to engage in the make-believe of a pseudo-African dance whose cringing racist parody is worthy of Fred Astaire’s Swing Time. Fetishizing the ‘Other’ (a stuffed elephant’s foot is a prominent trophy) in this ironic, late-night episode allows the characters to act out primitivist fantasies as a temporary respite from the exhaustions of modernity. In another episode modern technology takes over from primitivism to the same end. An aeroplane temporarily releases Vittoria into the clouds on a joy ride to Verona. Here and over the trees as she stands in the street after Piero has stood her up, Antonioni’s camera spreads its wings and flows. These are transient moments of aesthetic possibility and release within the unending process of engagement. It is here that the camera comes closest to the indexical registration of optical accidents and momentarily releases viewers from the unrelenting ironic awareness that they too are alienated modernists seeking distraction through film just as the characters do in their aimless and impulsive wanderings.

The oppressive effects of traditional works of art do not thematise the whole film yet dominate other episodes, such as the scene in the stuffy bourgeois apartment of Piero’s parents, where a classical bust, antique cabinets and a more conventional range of paintings extend the themes of the opening sequence in different thematic directions. Though it does not bear directly on art, perhaps the major parallel with the flipped picture frame at the beginning is the final shot of the film, which enacts the “Eclipse of the title. After a series of close-ups and a long holding shot, the street light is turned off, leaving the film in darkness before it ends. Few habitual events could better demonstrate the exercise of social control over public space. The extinction of the street light shows the way a breakdown in ordinary human relations with the world gives rise to a pervading sense of anxiety, uncanniness and angst. The shot terminates a plotless sequence of views that matches the discontinuous opening sequence. It projects an “impossible consciousness”, the filmic experience of watching something when no one is there to see it. The sequence is not devoid of human figures, however, though we have seen none of them before. The views feature the Roman suburb of EUR whose acronym stands for Exposizione Universale Roma. It was built as Mussolini’s ideal city for the 1942 World Fair and abandoned due to the war. The final sequence juxtaposes scenes from this impersonal realm that the main characters have haunted throughout, but we search for them in vain due to the same kind of narrative disruption as at the beginning. We mistake unknown figures for those we know due to superficial resemblances that must have been carefully planned, but feel as if they are due to our own projective habits. As our preconceptions are disabused, the effects of estrangement intensify. By abstracting space and evacuating human presence from the scene, the extinction of the street light intensifies the pre-existing effects of alienation. It embraces us in the terrifying intimacy of darkness, intensified by the sudden burst of discordant atonic music. This is no longer an evocation of ‘impossible consciousness’ for viewers are supremely present to a scene that cinematically enacts a collective panic attack.

The eclipse of the streetlight is supposed to have replaced the director’s footage of a real solar eclipse, which would have translated the film’s title too literally. [18] The most convincing interpretation of the ending I have found is that in this rare avant-garde film for mass audiences – its failure at the box office prompted coining of the term “Antoniennui” [19] – the extinguished light destroys the myth that film ever shows anything other than ideologically manipulated “reality”. [20] The film expires before it ends, leaving a black frame void of meaning, a “champ vide” or “empty frame”. It echoes the flipped frame at the beginning, but works on a different mode of consciousness. The extinction of the streetlight does to filmic time what the picture frame did to filmic space: the ending before an ending matches a frame within a frame. Right from the start the over-determined bourgeois frame reminds the viewer that even a randomly fragmented narrative is ideologically framed as “an alternative world” [21] at a time when the “real” world was framed by the off-screen menace of atomic war. At the beginning atomic war is symbolised by the mushroom-shaped EUR water tower through Riccardo’s window while at the end newspaper headlines declare “La Gara Atomica” and “Peace is Weak”. The reversed picture frame and the champ vide after the extinction of the streetlight recall the ontological paradox that Stanley Cavell credited to all cinema: “film screen both screens me from the world it holds … and it screens that world from me”. [22] Our consciousness of these instances of reflexive mediation produces the opposite effect to the motorised empathy film shares with history painting: it suspends belief in filmic illusion. In L’Eclisse the backdrop of possible nuclear annihilation is the chief source of the sense of characters adrift in a nihilistic void searching for distraction and relief from boredom. It is this that calls forth the reflexive apparatus of the film, keeping us in a stance of negativistic modernist self-critique obliging us to recognise ourselves in the characters’ alienated aimlessness.

Turning to the art world of Antonioni’s day, I want to show how the cameo of the reversed picture frame at the beginning of L’Eclisse resonates with the European institutional discourse of the death of painting as Antonioni was making this film. It had been a long time coming. As far back as 1820-21 Hegel’s Lectures on Aesthetics gave it philosophical momentum by claiming that the driving impulse of art, as a vanishing moment of thought, had passed over into philosophy. [23] “Today painting is dead”, lamented the academic painter Paul Delaroche around 1839 after encountering the daguerreotype, the first successful photographic process. [24] It seemed to him, as to many others, that painting had ceded to technology the primary mimetic purpose of Western art since the Renaissance. Marcel Duchamp, however, gleefully welcomed these developments in writing to the photographer Alfred Stieglitz in 1922: “You know exactly what I think of photography. I would like to see it make people despise painting until something else will make photography unbearable”. [25] He relished the death of “retinal art” because it emancipated “the beholder’s share” from what he considered as the institutional stranglehold of traditional art forms. [26] Five years before L’Eclisse he wrote: “All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act”. [27] Henceforth it is “the beholder’s share” that “transubstantiates” matter into art. [28] Indeed, since the Salon des Refusés discredited the Official Salon in the 1860s, where the revolutionary art of Jacques-Louis David had once galvanized bourgeois power against the aristocracy, “practices of negation” had begun to permeate French Impressionist and modernist painting as art withdrew from bourgeois constituencies and lost public relevance through “lack of an adequate ruling class to address”. [29]

T. J. Clark has enumerated:

The refusal of simple equivalences between particular aspects of a representation and aspects of the thing represented: the Impressionists’ broken handling, Cezanne’s discarding of the usual indicators of different surface textures, the Fauves’ mismatching of colour on canvas with colour in the world out there. Deliberate displays of painterly awkwardness, or facility in kinds of painting that were not supposed to be worth perfecting. Primitivism of all shapes and sizes. The use of degenerate or trivial or “inartistic” materials. Denial of full conscious control over the artefact; automatic or aleatory ways of doing things. A taste for the margins and vestiges of social life; a wish to celebrate the “insignificant” or disreputable in modernity. The rejection or parody of painting’s narrative conventions. The false reproduction of painting’s established genres (Manet was a past master at this). The parody of previous powerful styles (Abstract Expressionism in the hands of Johns or Lichtenstein). And so on. [30]

All these practices pulled visual art away from the traditional painting of classical, Christian and nationalist themes and the literary anecdotalism that Clement Greenberg had castigated as “that virus of the eye”. [31]

Antonioni uses negational practices in a recondite parody of the Apollo and Daphne tradition in painting. As Riccardo reaches out to grasp Vittoria, the mushroom water tower outside the window flattens onto his head to transform him into the semblance of an Apollonian “dickhead” (testa di cazzo in Italian), [32] freezing the big hair of his arboreal Daphne. [33] The anachronistic humour of this cold, anxious shot is caustic but remote, as if passionate empathy and cynical detachment could coexist in the same viewer.

Riccardo, Vittoria and the water tower, Michelangelo Antonioni, L’Eclisse, 1962, film still

Antonio Pollaiuolo, Daphne and Apollo, ca. 1470-80, oil on wood

If modernist strategies of negation produced painting whose surfaces flattened the deep space in which stories can be told, they culminated in the 1960s art world with the rejection of painting in favour of the unframed, interactive creativity of participatory media, whose purpose was to repudiate traditional spectatorial distance. These new forms included Antonioni’s films themselves, praised by Umberto Eco in Opera Aperta (1962). Published in the same year as L’Eclisse appeared, this book is often credited with the inspiration to build upon the prior hybrid forms of collage, readymades and Vertovian montage, and so provide the rationale for new art forms, including mixed media, installation, performance, body, action and object art, minimalism, conceptualism and video art. These forms bear out its claim that “work in movement” revises the relationship between artist and audience to produce “a new mechanics of aesthetic perception”. In devising “new communicative situations” it required the subordination of product to process to persuade audiences to abandon the passive uses of art in favour of the active constitution of meaning by those who use art. The urgency of the audience’s practical and imaginative needs, so it was argued, should replace the elitist ideological agendas usually promulgated by mimesis. [34]

But what became of paintings within cutting edge art practice of the early 60s? As representations they were no longer regarded as “’natural’ analogues for human experience”, [35] but became object-events defined by the, context of audience participation. In the Italian works that started with Lucio Fontana, Piero Manzoni and Alberto Burri and were later associated with the Arte Povera movement, paintings became mere surfaces to be cut, drilled, burnt, torn or attacked. “Finally”, as Peter Weibel comments, “only the empty frames of paintings, or just the backs of paintings would be shown”. [36]

Fig 8. Giulio Paolino, Senza Titulo, 2009

Giulio Paolini’s Senza Titulo, 1961, a back within a back within a back; another Paolini with the same title, 1962, consisting of a paintbrush in a pot of painted balance on the lower strut of an empty frame sealed only with transparent plastic foil; Piero Manzoni’s Living Sculpture, 1962, where the artist does away with the painting and signs the back of the naked model instead; Robert Rauschenberg, Homage to David Tutor, 1961, where in the company of other artists, Rauschenberg is wired for sound as he paints a canvas with a clock on it that the audience cannot see. When the alarm on the clock goes off the cluster of performances stop and a bell boy wraps the painting and takes it away without anyone ever seeing its front until it turns up in a Berlin gallery some years later. Roy Lichtenstein’s Masterpiece (1962) depicts the artist receiving adulation from his girlfriend for a painting reversed against a wall that no one call tell is a masterpiece or not. Antoni Tàpies’ Reversed Canvas, 1962 consists of an ancient stretcher back with window fittings in the shape of a crucifix turned against us with the enigmatic sense of a culture hidden from Franco’s reactionary regime.

Fig 9. Antoni Tàpies, Stretcher on Canvas, 1962

These and many more paintings were part of the intellectual climate in which Antonioni made his film. At a time when European cinema was staking a claim to serious artistic status in the context of a crisis in traditional notions of art, L’Eclisse implicitly sides with these radically negational forms of contemporary art (but excluding abstract expressionist art, to judge from the opening sequence in Riccardo’s flat). When Vittoria extracts the ashtray from the picture frame it is done within an understanding of what would become Arte Povera’s challenge to the cult of valuable art materials and beautiful subject matter. Acknowledging post-war poverty, Alberto Burri made paintings out of the roughest sacking, while Manzoni presented cans of his own excrement as works of art. These were “materials that might permit a ‘poor’ artist to create works of potentially “rich” art”. [37] For Vittoria’s feminine, bourgeois aesthetic, painting must still be “beautiful”. By removing the ashtray she takes what is ugly out of the frame to beautify her composition. Thus the film takes possession of what she rejects as ugly, but her own aesthetic attitude is negated once we view the back of the frame. Here, as in many instances throughout the film, subtle formal devices hinge character point of view with metacinematic critique: our view of the painting is prised away from hers when we realise her hand on the frame puts us in a different viewing position from her own, the director’s position in fact. [38] While we face the frame head on, she must be standing to our right, reminding us that she is not the only vehicle of consciousness in the film.

In one sense the turned canvases of this period constitute a cry of mourning for the death of painting in a technological age that has rendered it obsolete. Several stretcher bars of reversed paintings, including Tàpies’s, are unmistakably cruciform, suggesting martyrdom. Generally, however, the turned canvases of this era are opera aperte suggesting emancipation. As the window closes on fixed representation, another opens on the auratic presence of object-events whose meaning is viewer-determined. In rejecting the traditional arts assembled in Riccardo’s flat, the view of Vittoria on the reversed side of the picture frame reenacts this change.

But I have also claimed that L’Eclisse is as hostile towards the mass medium of popular film as it is towards traditional art. As Antonioni insisted a year after its release: “once the two or three rules of cinematography have been learned, nothing remains but to break them”. [39] The opening sequence deploys “a diverse set of techniques to frustrate our expectations of conventional film narratives”. [40] I have already cited a number of negational strategies in the opening sequence, to which can be added disjunctive eyeline match shots, mismatching screen directions as the characters move towards or away from each other … the high key and low contrast of the photography and the adoption of bizarre viewpoints, all of which accord a “lack of naturalistic interest in the picture” that breaks with film tradition. [41] Like Vertov Antonioni was hostile towards narrative film drama, but unlike Vertov he realized that in order to activate that hostility in the viewer it was necessary to include narrative for contrast with, non-narrative techniques. Gavriel Moses explains that:

The general structure of the opening sequence breaks down into an alternation between what may be called “normal” or conventional cinematic exposition and what seems like the cinematic equivalent of “poetic” language. It is evident that large sections of the sequence attempt a plain and faithful “realistic” exposition of events, while others diverge in the direction of extreme formalism. Often the realistic and coherently causational stream of events is interrupted by a flow of poetically structured images, non-sequential moments of the action “frozen” at some significant instant. [42]

I have argued that L’Eclisse represents experimental film in allegiance with participatory new media. What, then, is the relationship between the film’s hostility to traditional art on the one hand and popular film narrative on the other? How can they both serve the interests of experimental film technique? The apparent contradiction is resolved if we consider their relationship as a war that sets them against each other.

We have already seen how the change from recto to verso views of the picture frame both narrates Vittoria’s decision to leave Riccardo at the subliminal level and suspends our belief in narrative at the meta-level. We have also examined the formal means by which the film connects these different levels of meaning. The whirring fan in the same opening sequence achieves a similar double assault on film narrative and traditional artistic techniques by a reflexive allusion to both media. Vittoria’s first appearance in the film brings to David Rosenfeld’s mind the desire for Antonioni to have drawn the film closer to a Vermeer painting. “The composition of this first meeting of Vittoria would be complete if only we could discern, however vaguely, Antonioni’s hand in the mirror of Riccardo’s apartment, as we view the foot of Vermeer’s easel in the mirror of his painting, ‘The Music Lesson’”. [43] But considered as a reflexive substitute for the director’s camera analogous to Vermeer’s easel leg in the mirror, the electric fan swinging from side to side in the opening sequence satisfies this desire completely. The halting choreography of converging and diverging rhythms of the fan, the episodic movements and turning gazes of the characters, and the director’s alternately fixed or panning camera angles confers the quality of estranged anthropomorphism on all of these human and inanimate processes. The fan resembles a dispassionate automaton, making either the camera seem alive when we know it is dead or the characters dead when we know they are (or were) alive. The episode does not of course invoke Vermeer’s painting, but since it follows the reversal of the picture frame so closely, the fan can be read diachronically as a contrasting representative of the camera, while panning synchronically across all the static art forms in the room in gyrating opposition to their mute traditionalism. The emotional historiography of L’Eclisse uses cinematic experiment to lift the dead hands of traditional art and popular cinema from future imaginings of erotic intimacy and social integration.

Fig 10. Jan Vermeer, The Music Lesson (1662-65), oil on canvas

References:

[1] See Peter Brunette, The Films of Michelangelo Antionioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 73-89, Michel Butor, ‘Rencontre avec Antonioni,’ Les Lettres francaises, no. 880 (1961), 15-21, and Jacopo Benci, ‘Michelangelo’s Rome: Towards an Iconology of L’Eclisse’, in Cinematic Rome, ed. Richard Wrigley (Leicester: Troubador, 2008), pp. 67-78.

[2] Gavriel Moses, Eclipse (Italy, 1962), The Opening Sequence, 12 min.: NOTES AND ANALYSIS (London: Macmillan Films, 1975), p. 9.

[3] Boris Groys, “Iconoclasm as an artistic device/Iconoclastic strategies in Film”, in Iconoclash: Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion and Art, ed. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2002), p. 282.

[4] Gerhard Wolf, “Christ in His Beauty and Pain: Concepts of Body and Image in an Age of Transition (Late Middle Ages and Renaissance)”, The Art of Interpreting: Papers in Art History from The Pennsylvania State University, Volume 9 (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University, 1995), pp. 164-197.

[5] Thomas Puttfarken, The Discovery of Pictorial Composition: theories of visual order in painting 1400–1800 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000), pp. 49–62.

[6] Rensselaer W. Lee, “Ut Pictura Poesis”: The Humanist Theory of Painting (New York: Newton, 1967).

[7] Anne Jensen Adams, Public Faces and Private Identities in Seventeenth-century Holland: Portraiture and the Production of Community (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 100.

[8] Michael Tierno, Aristotle’s Poetics for Screenwriters: Storytelling Secrets from the Greatest Mind in Western Civilization (New York: Hyperion, 2002).

[9] Jennifer Barker, “The Tactile Eye”, paraphrased by John Rhym, “Towards a Phenomenology of Cinematic Mood: Boredom and the Affect of Time in Antonioni’s L’Eclisse”, New Literary History, 43 (2012): p. 479.

[10] Moses, Eclipse p. 26.

[11] I am grateful to John Payne, Senior Conservator of Painting at the National Gallery of Victoria, for this observation.

[12] David Saul Rosenfeld, Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Eclisse: a broken piece of wood, a matchbook, a woman, a man (2007), chapter 6, [http://www.davidsaulrosenfeld.com/chapter6.html].

[13] Rosenfeld, Michelangelo Antonion’s L’Eclisse, chapter 2, [http://www.davidsaulrosenfeld.com/chapter2.html].

[14] Richard C. Trexler, Public Life in Renaissance Florence (New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, San Francisco: Academic Press, 1980), p. 47.

[15] William Arrowsmith, Antonioni: the Poet of Images, ed. Ted Perry (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 73.

[16] Moses, Eclipse, p. 10.

[17] Michelangelo Antonioni, “Making a Film is My Way of Life”, Film Culture, 24 (1962): p. 44.

[18] Michelangelo Antonioni, The Architecture of Vision: Writings and Interviews on Cinema (New York: Marsilio Publishers, 1996), p. 59.

[19] Andrew Sarris, “No Antoniennui”, Focus on Blow-Up. Ed. Roy Huss (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1971), pp. 31–35.

[20] Adriano Aprà in Adriano Aprà and Carlo di Carlo, “Elements of Landscape: L’Eclisse”, Interviews, produced by Kim Hendrickson, on Michelangelo Antonioi’s L’Eclisse: Disc Two: The Supplements (Criterion Collection, 2005): “The light in the very last shot, a streetlight flooding the screen, rapidly transforms into total darkness where the words ‘The End’ appear. That also is the eclipse of realism. This film attempts – within mainstream cinema, not experimental cinema – to be an avant-garde film, one of experimentation – I’d call it ‘overground,’ instead of the classic ‘underground’”.

[21] Richard Reña, sound commentary on Michelangelo Antonioi’s L’Eclisse: Disc One (Criterion Collection, 2005).

[22] Rhym, “Towards a Phenomenology of Cinematic Mood”, p. 490.

[23] Margaret Iverson and Stephen Melville, Writing Art History: Disciplinary Departures (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2010), pp. 158-9.

[24] Paul Delaroche, quoted in Douglas Crimp, “The End of Painting”, October 16 (1981): p. 75.

[25] Marcel Duchamp, The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (New York: Da Capo Press, 1973), p. 165; originally published in Manuscripts, No. 4 (New York, December, 1922).

[26] E. H. Gombrich, “The Beholder’s Share”, Art and Illusion: a Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961), part 3, pp. 181-287.

[27] Marcel Duchamp, “The Creative Act”, in Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: a Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings, ed. Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), p. 819.

[28] David Hopkins, After Modern Art, 1945-2000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 34.

[29] T. J. Clark, “Clement Greenberg’s Theory of Art”, Pollock and After: the Critical Debate, ed. Francis Frascina (London: Harper & Row, 1985), p. 59. See also Hans Belting, The End of the History of Art?, trans, Christopher S. Wood (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1987), p. 40.

[30] ibid., 55n.

[31] Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting”, Art and Literature, 4 (1965): pp. 193–201.

[32] Rosenfeld, Michelangelo Antonio’s L’Eclisse, chapter 2, [http://www.davidsaulrosenfeld.com/chapter2.html].

[33] Rosenfeld, Michelangelo Antonio’s L’Eclisse, chapter 2, endnote 9, [http://www.davidsaulrosenfeld.com/endnotes.html].

[34] Umberto Eco, The Open Work (1962), trans. Anna Cancogni (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989), pp. 22-23 and passim.

[35] Hopkins, After Modern Art, p. 98.

[36] Peter Weibel, “An End to the ‘End of Art’? On the Iconoclasm of Modern Art”, in Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (eds), Iconoclash: Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion and Art (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2002), p. 614.

[37] Rosenfeld, Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Eclisse, chapter 2, [http://www.davidsaulrosenfeld.com/chapter2.html].

[38] See Michael O’Pray, Film, Form and Phantasy: Adrian Stokes and Film Aesthetics (Oxford: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), p. 128.

[39] Michelangelo Antonioni as quoted by Philip Strick, “Antonioni, ‘A Motion Monograph’,” Motion, 5 (March 1963): p. 23.

[40] Rhym, “Towards a Phenomenology of Cinematic Mood”, p. 479.

[41] Moses, Eclipse, p. 10.

[42] ibid.

[43] Rosenfeld, Michelangelo’s L’Eclisse, chapter 2, [http://www.davidsaulrosenfeld.com/chapter2.html].