Scott Balcerzak’s Buffoon Men: Classic Hollywood Comedians and Queered Masculinity continues the tradition of queer scholarship committed to re-reading mainstream cultural texts. As his book title suggests, his study focuses on a selection of Hollywood comedies specifically structured around male comic stars produced during the height of the studio system from the early sound era to the immediate post-war period.

Balcerzak opens by ruminating on Groucho Marx’s backhanded quip, “I would never want to belong to any club that would have me for a member”, using it to introduce the major theme of his study: membership within the hegemonic fraternity of elitist, white, male, heterosexual Americans. Throughout the book, Balcerzak returns to a particular preoccupation America has repeatedly had with masculinity, centred on the belief that the American male has, through urbanisation and domestication, become increasingly feminised. He reasons that it is the social pressure for men to conform to a rigid set of performative practices attributed to maleness that made these comedians so popular, for they dared display alternative expressions of being and behaving that confront the validity of the dominant construction of manhood.

In a book dedicated to queered masculinity, Balcerzak’s first case study is amusingly apt in its focus on the work of Mae West, whose star persona was inspired by her early associations with New York’s fringe drag culture. As well as providing insight into the history of drag in America and several of its leading personalities, Balcerzak convincingly argues that West’s sexually aggressive persona was itself a drag performance that ridicules the performative nature of gender. He notes that the genre of “comedian comedies” with which he is chiefly concerned is dominated by male personalities and generally excludes female performers. West, it is argued, is one of the few female comedians who managed to rise to the top of a notoriously male-centric vocation. By way of a discussion of her film My Little Chickadee, Balcerzak introduces West’s co-star and the subject of the following chapter, W. C. Fields. Emphasis in placed upon how the popular comedian’s incompetent “antisocial” alcoholic con man persona parodied normative masculinity and the roles it occupies – husband, lover, father, protector and provider – by utterly failing in his performance of them.

Chapter three focuses on Jewish comedian Eddie Cantor. Through his exploration of the “nebbish” – a Yiddish term for a small, weak, cowardly male – Balcerzak provides an in-depth analysis of Cantor’s feminised and homoerotic screen persona. He provides a close look at Cantor’s manifold uses of blackface, charting its origins and significance to Jewish performers while highlighting the unique differences between Cantor and Al Jolson’s use of the art form. The chapter also examines the whitewashing of popular Jewish actors in Hollywood and the complexities involved in assimilating the Jewish pariah into popular culture, while ensuring his exclusion from privileged white culture.

The following chapter focuses on influential radio personality Jack Benny who, with his popular 1930s radio show The Jack Benny Program, provided the prototype for character-based television comedy that today is de rigueur. Describing Benny’s radio character as a vain dandy, Balcerzak explores how the medium of radio afforded Benny opportunities to push the queer elements of his comedy further than was possible with visual media.

The second half of Balcerzak’s book analyses the work of three male comedy duos: Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsey, and Bud Abbott and Lou Costello. Laurel and Hardy are presented as a feminised duo, differentiated from other comedy pairings of an emasculated male character prone to fits of hysteria with a masculine straight man. The chapter centres on the duo’s 1933 film Sons of the Desert in which they are members of an ineffectual fraternity whose purpose is to make “real men” of its members. This leads into a fascinating historical account of the rise and demise of fraternal societies in America during the first half of the twentieth century. Balcerzak briefly discusses the 1987 documentary Revenge of the Sons of the Desert which looks at the worldwide Laurel and Hardy “appreciation society” that models itself on traditional American fraternities, only to parody them with carnivalesque rituals that subvert authority, order and propriety.

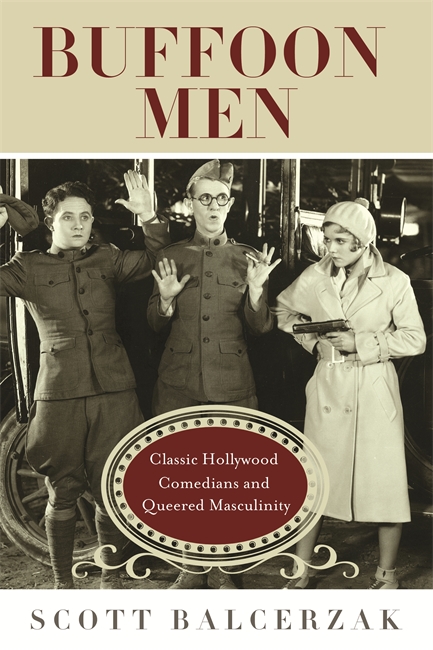

Continuing his analysis of fraternal bonds, Balcerzak’s final chapter compares changes in the construction of masculinity in the decade leading up to America’s entry into the Second World War. His analyses of Wheeler and Woolsey’s comedy Half Shot at Sunrise (1930) and the Abbott and Costello vehicle Buck Privates (1940) traces Hollywood’s shift towards increasingly conservative representations of homosocial relations in the armed forces. While Wheeler and Woolsey’s First World War soldiers mock rank and revel in sexual frivolity, Abbott and Costello’s film focuses on the recently introduced peacetime draft, issuing a rallying call to national service that is presented as a masculine rite of passage as, in between the hijinks, its protagonists are transformed from a motley crew of softies into a disciplined team of toughened privates.

Buffoon Men begins and ends with a discussion of contemporary comedians, arguing that an essential role of the male comic has long been that of a satirist interrogating and problematising contemporary constructions of patriarchal heteromasculinity. Unfortunately, Balcerzak’s concluding chapter is his least compelling, as he attempts an all-too brief summary of popular American comedy since the 1940s that devolves too much into generalisations. His discussion of black comedians is limited to Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy, the latter described as a “heterosexually aggressive leading man” (195). But Murphy’s early hypermasculine persona typically targeted racial stereotypes and parodied white male insecurity, while Boomerang (1992) conspicuously plays with his persona, satirising his prized virility as it is undermined by an increasing emasculation at the hands of powerful women. Balcerzak also argues that female comedians have rarely enjoyed the levels of success of their male counterparts, and that most breakthrough performances by women have taken place on television. He is dismissive of most female comedians with the exception of such recent Saturday Night Live alumni as Tina Fey, suggesting this new generation of comediennes represent a change in direction for women in comedy as writer/producers. Surprisingly, Balcerzak fails to mention Better Midler in his discussion of popular female comedians. Considering his first case study was focused on Mae West, it seems fitting that he should include a discussion of Midler, especially as the two women share similar backgrounds, honing their talents in exclusively queer environments, and are both popular gay icons. In early December 2013, Variety fell victim to an online hoax when it published an article claiming that Midler was to play Mae West in an HBO biopic to be directed by William Friedkin and written by Harvey Fierstein. The prank successfully generated significant online buzz that generally praised the casting of Midler as West, further demonstrating the similarities between the two stars.

While the scope of Balcerzak’s book is ambitiously broad, each of his case studies is supported by meticulous research and an accessible writing style. It will prove a useful resource for researchers, teachers and students of gender studies, film history and Hollywood comedy.