There has been a resurgent interest in media production studies recently, one that has significantly redirected attention away from macro studies of patterns of ownership and consumption towards an interest in labour, in the actual activities of media workers. David Hesmondhalgh and Sarah Baker’s recent study, Creative Labour (2010) examines the types of work that characterise magazine journalism, music and television, and the ethical as well as economic questions to which they give rise. John Thornton Caldwell’s influential study Production Culture (2008) analyses the self-representations, self-critiques and ‘cultural self-performances’ of workers in the film and television industries encouraging an attention to the multifaceted nature of production practices and how they are embedded within industry rituals of behaviour. Two important collections of essays appeared in 2009: Media Industries: History, Theory and Method edited by Jennifer Holt and Alisa Perren, and Production Studies edited by Vicki Mayer, Miranda Banks and Caldwell. Mayer’s own contribution to the latter argued that production studies should attempt to ground broad social theories by examining specific production sites, with a central focus on the relationship between workers’ material conditions and the formation of their subjectivities, thus between labour and identity.

In Below the Line, Mayer develops these concerns, investigating an “expanded conceptual field for television production” (23) through a series of four case studies, which, as the title suggests, moves discussion away from the conventional focus on an elite group of “above the line” workers who have conspicuous power and control over the production process and whose names are conspicuously highlighted in the credits, to those whose labour is uncredited, ignored or invisible. She argues that production studies’ attention to this select few “creative professionals” has colluded with the media industries’ own self-promotion and she critiques the mechanisms through which “creativity” and “professional” have been constructed historically in particular ways. These conventional paradigms urgently need to be rethought because the media industries themselves are changing rapidly as the “new media economy” generates novel networks and work spaces, unsettling established hierarchies and blurring the boundaries between “the material and symbolic dimensions of labor” (19).

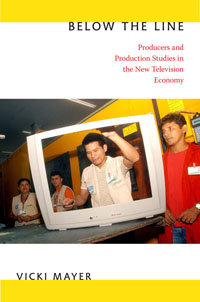

The first of four case studies – each based on participant ethnographic fieldwork – analyses the labour embodied by mainly female assembly line workers, in an electronics factory in the international industrial zone of Manaus, Brazil, who supply television sets for Mitsubishi. Although this would seem an obvious case for studying the mechanised routines of mass production, Mayer argues that the operatives show creativity and ingenuity, particularly when working on a new component, in devising physical and mental variations that help them reduce stress or boredom. Through this deliberately provocative example, highlighting unconsidered actions performed in a remote location far from the centres of corporate power, Mayer subverts the conventional hierarchies of recognition and reward, of professionalism and creativity.

Mayer’s second study charts the emergence of a new generation of media professionals, male videographers who shoot soft-core video footage during the ten-day Mardi Gras festival in New Orleans. They work for corporations “organized like television studios” (72), which market soft-core entertainment packaged into series such as Girls Gone Wild, for the lucrative market of 18-24 year old males. Despite the low status of their product, the cameramen take pride in their skills, professionalism and dedication to their craft, which they regard as an art form.

The third study analyses those who cast reality television programmes. Because “being yourself” in front of the camera and projecting a “character” that will have audience appeal is a difficult skill, these reality casters exercise judgement and accumulated expertise in finding their subjects and in preparing them for their “role”. In doing so they forge a generic consistency for reality television as well as creating a buzz around the casting to generate interest, building an eventual audience for the programme. Mayer argues that they perform a liminal role, acting as friendly and confidante to the public, but as a skilled professional for television stations and sponsors.

The final study examines another liminal role, that of local citizen regulators. These volunteers, agents of neither state nor market, but acting as a supposed bridge between them as representatives of the public, perform an important function. But their work is another form of invisible and in this case uncompensated labour, even though such roles are proliferating in a deregulated marketplace. This chapter brings to the fore Mayer’s ethnographic approach as she draws on her own experiences as a regulator in two different towns, San Antonio, Texas and Davis, California. Mayer scrupulously interrogates her own identity formation as a citizen consumer who is also an academic, and a middle-class Caucasian woman.

The compelling detail of these case studies unsettles conventional paradigms that ascribe creativity and professionalism to a relative narrow range of tasks performed by an elite group. They fulfil Mayer’s aim to “repoliticize the ordinary” (186) by revealing the often hidden issues of gender, ethnicity and class as well as location and place, which open out into her wider critique of the self-deluding “rhetoric of the creative economy”, by exposing “its implicit material inequalities” (176). The Conclusion reviews the paradoxical nature of the new media economy, which has given a much wider range of people access to production whilst at the same time offering workers less security, safeguards and stable employment. Most tellingly, Mayer notes that workers are now engaged in complex but also often unconscious exercises in making themselves marketable as work starts to invade every aspect of social life. Overall, this volume succeeds in enlarging the scope of television production studies significantly. It should encourage other researchers to cast their net widely.