(First published in Expanded Cinema, P. Dutton & Co., Inc., New York 1970 )

Susan Sontag once defined the “two principal radical positions” in contemporary art as that which recommends the breaking down of distinctions between genres, and that which maintains or upholds those distinctions: on the one hand seeking a “vast behavioral magma or synaesthesis”; on the other hand pursuing “the intensification of what each art distinctively is.” She concluded that the two positions are essentially irreconcilable except that “both are invoked to support a perennial modern quest – the quest for the definitive art form.”1

Surely the definitive art form is not anti-environmental, as art must be when viewed in terms of genres: to isolate a “subject” from its environs by giving it a “form” that is art denies the natural synaesthetic habitat of that subject, physical or metaphysical, icon or idea. In the progression of art history through Form, Structure, and Place, the idea of art as anti-environment has long been surpassed. This is not to say that any activity that seeks to discover the essence of a medium is somehow disreputable; on the contrary, the exclusive properties of a given medium are always brought into sharper focus when juxtaposed with those of another.

Thus, in intermedia theatre, the traditional distinctions between what is genuinely “theatrical” as opposed to what is purely “cinematic” are no longer of concern. Although intermedia theatre draws individually from theatre and cinema, in the final analysis it is neither. Whatever divisions may exist between the two media are not necessarily “bridged,” but rather are orchestrated as harmonic opposites in an overall synaesthetic experience. Intermedia theatre is not a “play” or a “movie”; and although it contains elements of both, even those elements are not representative of the respective traditional genres: the film experience, for example, is not necessarily a projection of light and shadow on a screen at the end of a room, nor is the theatrical experience contained on a proscenium stage, or even dependent upon “actors” playing to an “audience.”

Carolee Schneemann: Kinetic Theatre

Pioneer intermedia artist Carolee Schneemann describes Kinetic Theatre as “my particular development of the Happening, which admits literal dimensionality and varied media in radical juxtaposition.” She works with untrained personnel and various materials and media to realize images that range from the banal to the fantastic, images which, in her words, “dislocate, disassociate, compound, and engage our senses to allow our senses to expand into primary feelings, as well as the sensitive relatedness among persons and things.” Through these methods she seeks “an immediate, sensuous environment on which a shifting scale of tactile, plastic, physical encounters can be realized. The nature of these encounters exposes and frees us from a range of aesthetic and cultural conventions.”

Since 1956 Miss Schneemann has continually redefined the meaning of theatre. Though New York is her home, she has staged radical intermedia events throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe. Her best-known works include Snows, presented as part of New York’s Angry Arts Festival in 1967; Night Crawlers, staged at Expo ’67 in Montreal; Illinois Central (1968); and the film Fuses. I asked what directions she will follow in future intermedia work.

CAROLEE: I’m moving more into technology and electronics. My long-range project is completely activated by the spectators. I’ll sensitize the audience through a performance situation in which detailed film images are set off by the audience as they move into the performance environment. They’ll activate overlapping timed projectors. If they want a film to be shown again they’ll have to figure out what they did to make it start in the first place. These films will show detailed aspects of performance situations: touching, handling, moving. Then as the participants move in other directions the actual materials shown in the films will be introduced. They’ll fall from the ceiling or be tossed out of boxes.

GENE: I take it you find film/actuality interactions effective in involving the audience.

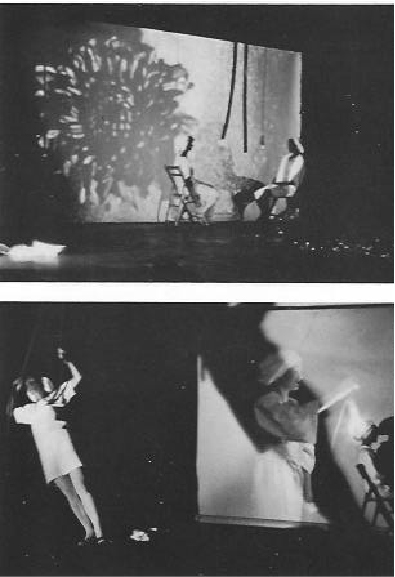

Carolee Schneemann: Night Crawlers. Expo ’67. Live performers (right) contrasted with film projection.

CAROLEE: Night Crawlers, which I did at Expo ’67, was very successful in this manner. I juxtaposed my Vietnam film with a little Volkswagen that drove in front of the film and stopped. It was stuffed with foam rubber. My partner and I performed a complex of physical handling on top of, and inside the VW while another person was pulling all the foam out. It was a very intimate and humorous event in front of this horrifying Vietnam film. Before it began, a girl and I went through the audience and stepped on their shoulders and knees and gave each person candy and cake. We spoke to them. They got very turned on by the whole thing. At the end we brought them into the performance area and played lights and sound around them. They found elements of the environment that they could start to tear down. They began rather hesitantly, but after they ripped a couple of layers of paper there’d be a message greeting them, saying proceed, or directing them to paint cans. The point seems to be to let people work out of impulses that are blocked. If the situation is obvious they tend to be destructive. They’re working in daily life with outmoded kinds of repressions and resistances. They tend to get violent. So we try to open up an empathy between them and what we’re doing that they’re not consciously anticipating.

GENE: Do you always use film in your theatre pieces?

CAROLEE: Yes, I tend always to use it in some aspect of an environmental performance situation, primarily because of the intensification of information it gives, which may just be sensory information. And I use it to transform the environment. I tend to use film very formally. Every element that goes into the environment I’m working with is very carefully shaped in terms of scale, time duration, what’s going on in juxtaposition to a film. In Illinois Central there was a three hundred and sixty-degree visual environment that was changing and shifting all the time, composed of films and slides. And I like using slides against films because I can start and stop, overlap, black out, manipulate. I’ve been working with portable projectors so that the image can be shifted in space.

GENE: Do you work with body projections?

CAROLEE: Yes, and I find it always satisfying. I do a lot of performing just in the light of film projectors. So that it’s a very compacted image and there are no peripheral distractions. It becomes central to the environment without your really having the sense of film, because the bodies or forms of people are quite embedded in it.

GENE: Do you make your own films or work with found images?

CAROLEE: I animated the Vietnam film, shot it from stills with various lenses so that it seems as if it’s really moving. The images in that film were central to the development of Snows. My Snows movie begins with a very beautiful 1947 newsreel, a snowstorm, a fall of confetti during a parade, and ends with a car exploding and bursting into flames, then the Pope blessing people. One little horrific element after another: volcanic eruptions, ships going down… For my film Viet Flakes I shot a still of a Nationalist soldier shooting a Communist worker. It’s in three sections: he raises his gun, he leans forward, and the victim is lying there with a dark spot under his head. Then I got two newsreels of winter sports in Zurich during World War II while all hell was breaking loose everywhere else in the world. Then I made a little 8mm. film that played on our bodies, showed a New York blizzard and a car driving through the city. The projectors were either carried by hand or mounted on revolving stools.

GENE: How did you work with film for Illinois Central?

CAROLEE: I went out in advance and shot footage of empty horizons. Very slow, attenuated, linear footage. Then I borrowed about five hundred slides of the same landscape, this absence of form. And I used the slides stretched out against the film; while the film would have a certain kind of horizon line, I’d have six duplications of one slide horizon feeding into the film from all around the room. And then as the film shifted, slide images would shift. It wasn’t decorative. I use films and slides as compacted metaphors. It compounds the basic range of emotive material. It concretizes the event, girds it in. While the live physical movements are ambiguous and emotional, the films lend a banal insistence.

GENE: How do you think of your work in terms of their objective and subjective aspects, actuality versus illusion?

CAROLEE: I’ve always thought that I’m creating a sensory arena, and what you describe as kinetic empathy is very basic to the process. Because the information, in terms of what we’re able to feel, how much the audience is able to open up, be moved and touched – it’s all completely of the moment. There’s this strange sort of fulcrum of the individual sitting there without narrative or literary preparation to help him follow the action. It’s all involved in sensory receptivity. And I’m bombarding them, I’m giving them more than they can possibly assimilate at any one point. Unlike painting, which used to be my medium, where you could take a great deal of time. And the thing is, with a static element, the audience is actually being more active. You choose the time duration and manner in which you experience the object. But my theatre pieces call forth a whole other range of response areas. At the end of Snows many people in the audience are crying, and they don’t really know why, because it all happens with an incredible immediate speed and it’s overwhelming.

GENE: Some critics feel that many of the arts explore sensory awareness or perception well enough, but that one doesn’t come away with a knowledge of a subject having been learned.

CAROLEE: I know that criticism, but it doesn’t bother me because it’s not a real criticism anymore. What I’m going more toward is not merely a sensory or perceptual activation of the audience but an actual physical involvement. There no longer can even be the situation of performers who prompt or provoke the audience; we must deal directly with the audience itself as performers. As much as we so-called actors need to be performers, so they need to become performers, they need to enact that situation themselves. They must give over a kind of trust in the situation and go into it. I approach the audience with a great deal of care and tenderness, never being physically aggressive. The media information may be aggressive, but it’s going to stimulate them in ways that I have to be responsible for. So in terms of what that media might provoke, I have to oversee it.

GENE: So in a sense one goes to the theatre for completely different reasons than one used to; I hesitate to use the term “therapy,” but it seems to approximate something like that.

CAROLEE: We go to the theatre in search of inner realities because of the bankruptcy of the myths and conventions we’re used to dealing with in everyday life.

GENE: Perhaps in the near future, the whole process of living will be in this active seeking out of experiences.

CAROLEE: Right. What people really want is tactile confirmation, to be in touch with their physicality, to be able to communicate, and to grow, to touch one another and be touched. To get away from the somnambulism of contemporary life. We get all this information and there’s absolutely no way to react. You’re reading some horror in your newspaper while eating your doughnut. And if you were a natural animal you’d at least scream for fifteen minutes or chop the sofa into bits – assuming that you can’t go and change the thing that the media tells you is an outrage. So we’re trapped with all these fears of real impotence.

GENE: What other kinds of environmental projections have you done?

CAROLEE: Smoke, balloons, and buildings. In Montreal I did an outdoor event in which we carried the projectors and moved films across buildings at night, the images breaking into planes and fragments. The basic condition for my work is that whenever I find out how something works, what makes it go, say in regard to technology or any kind of element—even a human being – then I want to change it. As soon as I saw what a frame was for film I wanted to break it. I didn’t want to be stuck with that same rectangle.

Milton Cohen: Space Theatre

Milton Cohen, primary creative force behind the famous ONCE group of Ann Arbor, Michigan, has, since 1958, been developing what he calls “Space Theatre,” a highly original and effective environmental projection system for intermedia events. In fact Space Theatre is more concept than system, for Cohen continually modifies the hardware and architectural parameters of the theatre he has constructed in his studio. Yet the motive remains, as always, “to free film from its flat and frontal orientation and to present it within an ambience of total space.”

The core of Space Theatre is a rotating assembly of mirrors and prisms adjustably mounted to a flywheel, around which is arranged a battery of light, film, and slide projectors. The movement of the mirror/prism flywheel assembly determines image trajectories as the projections are scattered throughout the performance environment. In the past, Cohen has positioned rectangular and triangular panels about the space, to serve both as screens and as strategic points for image interaction with live performers. Often these panels have also been mobile—revolving, folding, or tilting – operated mechanically or by hand in a manner responsive to the image being projected.

Cohen’s most recent presentation was Centers: A Ritual of Alignments. Here the projection surface was a translucent circular core from which eight triangular screens radiated. Behind each screen was a photoelectric cell that activated sound and strobe-light events at various positions in the performance area. (Cohen often employs the amplified sound of the projection equipment itself as the aural complement of the imagery.) Behind the core, also described as the “target” area, was a slide projector.

Carolee Schneemann: Illinois Central. 1968. “I’ve always thought that I’m creating a sensory arena… we must deal directly with the audience itself as performers.” Photo: Peter Holbrook.

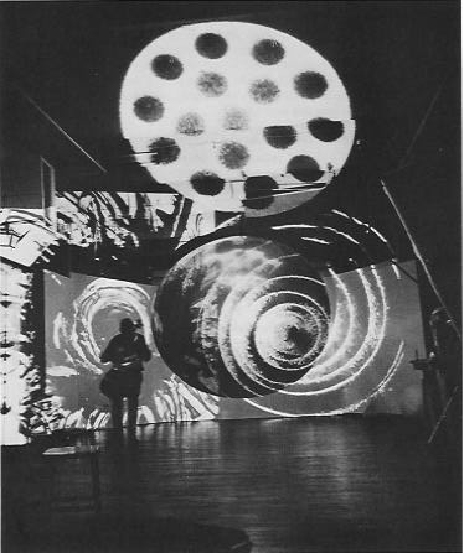

Centers: A Ritual of Alignments, as performed by Milton Cohen in his Space Theatre. 1969.

Film imagery was basic to the performance. Cohen adapted projectors to handle twelve-foot film loops projected sequentially on the fanlike screens, making one round every twenty seconds. Simultaneously various geometrical target patterns were rear-projected onto the core. The audience is seated on revolving stools in the twenty-foot area between the projection system and the screen. Their attention is polarized between the gyrating film and the free-floating slide imagery registering on walls and screens that define the total enclosure.

The multi-channeled sound is electronic, instrumental, and vocal, and moves in complex trajectories from speaker to speaker. The effect, according to Cohen, “is one of sound in flight; sound seeking target.” This theme of seeking out the target is carried over into the visuals through the manipulation of the projection console in a discrete sequence of maneuvers that search out the center. “When and if this centering is won,” Cohen explains, “the performance may proceed to the next film loop. But also ways must be discovered for other performers (live dance, live music, etc.) as well as the audience to contribute to the audiocentric and luminocentric probes. Ultimately there must be a common voyage for all to that identifying place which describes at once the center and the whole.”

The ONCE group has explored structures other than Space Theatre. Perhaps the best known American intermedia theatre event was their Unmarked Interchange (1965), in which live performers interacted outrageously with the Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers film Top Hat projected on a huge screen inset with movable panels, louvers, and large drawer-like sections. While a couple dined by candlelight at a table in one corner of the screen, a man read into a microphone from the pornographic novel, Story of 0, at the opposite end of the projection surface; periodically a girl walked across a catwalk in the center of the screen and hurled custard pies in his face. In another opening, a man played a piano. And over all of this Fred and Ginger danced their way through 1930’s Hollywood romantic escapism.

John Cage and Ronald Nameth: HPSCHD

Computer-composed and computer-generated music programmed by John Cage and Lejaren Hiller during 1967-69 was premiered in a spectacular five-hour intermedia event called HPSCHD (computer abbreviation for Harpsichord) at the University of Illinois in May, 1969. Computer-written music consisted of twenty-minute solos for one to seven amplified harpsichords, based on Mozart’s whimsical Dice Game music (K. Anh. C 30.01), one of the earliest examples of the chance operations that inform Cage’s work. Computer-generated tapes were played through a system of one to fifty-two loudspeakers, each with its own tape deck and amplifier, in a circle surrounding the audience. Cage stipulated that the compositions were to be used “in whole or in part, in any combination with or without interruptions, to make an indeterminate concert of any agreed-upon length.”

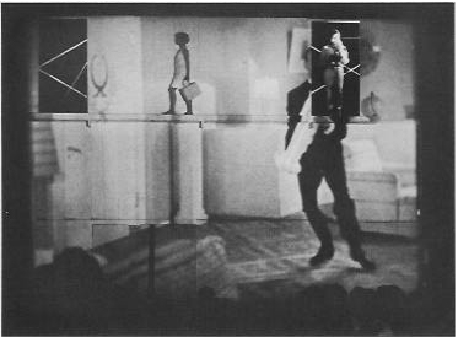

ONCE Group: Unmarked Interchange. 1965. Live performers interact with projection of Top Hat, starring Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers. Photo: Peter Moore.

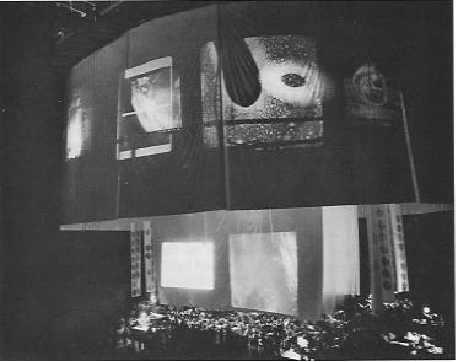

The university’s 16,000-seat Assembly Hall in which the event was staged is an architectural analogue of the planetary system: concentric circular promenades and long radial aisles stretching from the central arena to the eaves of the domed ceiling. Each of the forty-eight huge windows, which surround the outside of the building, was covered with opaque polyethylene upon which slides and films were projected: thus people blocks away could see the entire structure glowing and pulsating like some mammoth magic lantern. Over the central arena hung eleven opaque polyethylene screens, each one hundred feet wide and spaced about two feet apart. Enclosing this was a ring of screens hanging one hundred and twenty five feet down from the catwalk near the zenith of the dome. Filmmaker and intermedia artist Ronald Nameth programmed more than eight thousand slides and one hundred films to be projected simultaneously on these surfaces in a theme following the history of man’s awareness of the cosmos. “The visual material explored the macrocosm of space,” Nameth explained, “while the music delved deep into the microcosmic world of the computer and its minute tonal separations. We began the succession of images with prehistoric cave drawings, man’s earliest ideas of the universe, and proceeded through ancient astronomy to the present, including NASA movies of space walks. All the images were concerned with qualities of space, such as Méliès’ Trip to the Moon and the computer films of the Whitney family. The people who participated in HPSCHD filled in the space between sound and image.”

Milton Cohen’s Space Theatre, Ann Arbor, Michigan. 1969. Sight and sound move in

complex trajectories through a maze of shifting, revolving, faceted surfaces, seeking the target.

John Cage and Ronald Nameth: HPSCHD. 1969. Assembly Hall, University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana.

Fifty-two loudspeakers, seven amplified harpsichords, 8,000 slides, 100 films. Photo: courtesy of Ronald Nameth.

Over the central arena hung eleven opaque polyethylene screens, each one hundred feet wide and spaced about two feet apart. Enclosing this was a ring of screens hanging one hundred and twenty five feet down from the catwalk near the zenith of the dome. Filmmaker and intermedia artist Ronald Nameth programmed more than eight thousand slides and one hundred films to be projected simultaneously on these surfaces in a theme following the history of man’s awareness of the cosmos. “The visual material explored the macrocosm of space,” Nameth explained, “while the music delved deep into the microcosmic world of the computer and its minute tonal separations. We began the succession of images with prehistoric cave drawings, man’s earliest ideas of the universe, and proceeded through ancient astronomy to the present, including NASA movies of space walks. All the images were concerned with qualities of space, such as Méliès’ Trip to the Moon and the computer films of the Whitney family. The people who participated in HPSCHD filled in the space between sound and image.”

Seven amplified harpsichords flanked by old-fashioned floor lamps stood on draped platforms on the floor of the central arena beneath the galaxy of polyethylene and light. In addition to playing his own solo, each harpsichordist was free to play any of the others. Each tape composition, played through loudspeakers circling the hall in the last row of seats near the ceiling, used a different division of the octave, producing scales of from five to fifty-six steps. Only twice during the five-hour performance were all channels operating simultaneously; these intervals were stipulated by Cage.

Nameth has collaborated in several intermedia performances in addition to making his own computer films and videographic films, as well as conventional cinema such as Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable. In 1967 he worked with Cage in the preparation of Musicircus, an eight-hour marathon of sight and sound involving nearly three thousand persons – musicians, musical groups, orchestras, and composers in addition to a participating “audience” – all making music together.

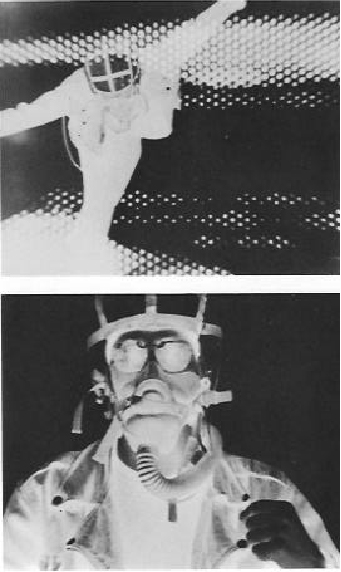

Two scenes from Ronald Nameth’s triple-projection film As the

World Turns for intermedia presentation L’s G.A. 1968-69.

In 1968-69 Nameth worked with Salvatore Martirano and Michael Holloway in a music/theatre/film presentation titled L.’s G.A. (Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address), which traveled throughout the United States and Japan. Described as a mixed-media event “for gas-masked politico, helium bomb, three 16mm. movie projectors, and two-channel tape,” L.’s G.A. was simultaneously a showcase for Martirano’s electronic tape compositions, Nameth’s multiple-projection cinema, and Holloway’s poetry. Nameth employed video imagery for his cinematic triptych As the World Turns, which he described as “the visual counterpart of Martirano’s music.” Depending on the physical limitations of the performance space, Nameth’s film was projected in the form of two smaller images side by side within a larger image, all three images adjacent to one another, or all three superimposed over one another.

Two scenes from Robert Whitman’s Prune Flat. 1965. Performers’ actions were synchronized with their film versions. Photos: Peter Moore

Robert Whitman: Real and Actual Images

The higher ordering principle of intermedia, or what might be called “filmstage,” is the simultaneous contrasting of an actual performance with its “real” projected image, so that the live performer interacts with his movie self. The New York artist Robert Whitman developed this technique in several variations during the period 1960-67, after which he abandoned film/theatre compositions for experiments of a more conceptual nature.

In The American Moon (1960) the audience viewed a central performance space from six tunnel-like mini-theatres whose openings were periodically blocked by plastic-and-paper screens on which films were projected. Persons in each tunnel could see through their screens to the flickering images on the screen of the opposite tunnel. Thus Whitman engaged cubic space, filmic space, real and projected images.

In his most famous work, Prune Flat (1965), Whitman utilized a conventional proscenium stage with a large movie screen as backdrop. Two girls performed various movements and gestures in person, while their filmed images performed the same action, and some different ones, on the screen. A third girl was dressed in a long white gown on which was projected a movie of herself removing her clothes. The girl’s physical actions were synchronized with the film being projected on her: she pretended to “throw” her skirt into the wings as the filmed image did so, etc. Finally a nude image of the girl was projected on her fully-clothed figure.

Aldo Tambellini: Electromedia Theatre

A pioneer in intermedia techniques, Aldo Tambellini has worked with multiple projections in theatrical contexts since 1963, always striving to cast off conventional forms, using space, light, and sound environmentally. In the spring of 1967 he founded The Black Gate, New York’s first theatre devoted exclusively to what Tambellini calls “electromedia” environments.

Aldo Tambellini: Black Zero. 1965. Shown at the artist’s Black Gate Electromedia Theatre in New York.

His archetype, fully realized in Black Zero (1965), is a maelstrom of audio-visual events from which slowly evolves a centering or zeroing in on a primal image, represented in Black Zero by a giant black balloon that appears from nothing, expands, and finally explodes with a simultaneous crescendo of light and sound. Literally hundreds of hand-painted films and slides are used, each one a variation on the Black Zero theme. In addition to electronic-tape compositions, the piece often is performed in conjunction with a live recital of amplified cello music.

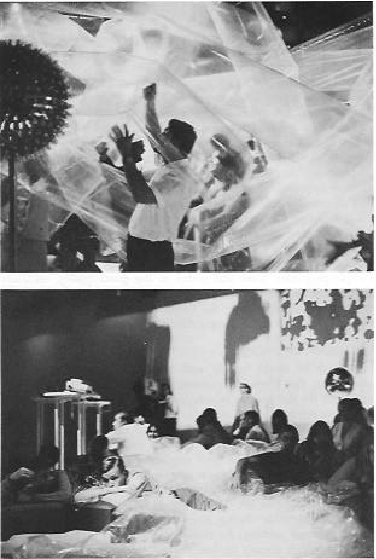

In Moon-Dial (1966) he collaborated with dancer Beverly Schmidt in a mixture of the human form with electronic imagery in slides, films, and sounds. With Otto Piene, he presented Black Gate Cologne at WDR-TV in Germany in 1968, which combined a closed-circuit teledynamic environment with multi-channel sound and multiple-projection films and slides as the participating audience interacted with Piene’s polyethylene tubing. Another version of this piece was conducted along the banks of the Rhine in Dusseldorf, with projections on a mile-long section of tubing.

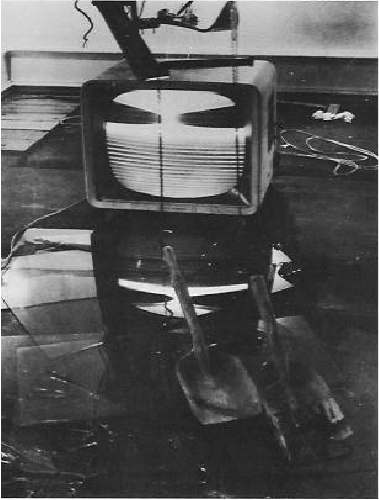

Wolf Vostell: De-Collage

Although he works largely with television, both as object and information, the German intermedia artist Wolf Vostell is most significant for the way in which he incorporates his video experiments into environmental contexts. Actually, his videotronic manipulations are no more sophisticated than the distortion of broadcast programs using controls available on any common TV set. But this is precisely the point of his work: rendering the environment visible as “art” by manipulating elements inherent in that environment.

Aldo Tambellini and Otto Piene: Black Gate Cologne. 1968.

Tambellini’s electromedia environment combined with Piene’s helium-inflated

polyethylene tubing at WDR-TV in Cologne, West Germany. Photos: Hein Engelskirchen.

Since 1954 Vostell has been engaged in what he calls “de-collage” art, or decomposition art. This is not to be confused with destruction art, fashionable during approximately the same period, for Vostell destroys nothing: he creates Happenings or environmental theatre in which already broken, destroyed, damaged, or otherwise derelict elements of the environment are the central subjects. Beginning in 1964 he made the first of several versions of one film titled The Sun in Your Head, described as “a movie of de-collaged television programs combined with occurrences for press photographers and audience.”

Wolf Vostell: Electronic Happening Room. 1968. One of Vostell’s de-collaged TV sets

in a multiple-projection intermedia environment designed to generate an awareness of

man’s relationship to technology. Photo: Rainer Wick.

Basically, Vostell seeks in all his work to involve the audience objectively in the environment that constitutes its life. He seeks to break the passivity into which most retreat like sleepwalkers, forcing an awareness of one’s relation to the video and urban environment. He sometimes describes his work as a form of social criticism employing elements of Dada and Theatre of the Absurd.

In Notstandbordstein (1969), the streets, sidewalks, and buildings of Munich became the “screen” on which a film was projected from a moving automobile. Vostell’s Electronic Happening Room (1968) was an environmental attempt to confront the participant with all the technological elements common to his everyday life, from telephones to Xerox machines to juke boxes. As in most of his work, complex multiple-projections of films and slides were combined with sound collages taken from the natural environment. In New York, in 1963, he exhibited a wall of six blurred (de-collaged) television sets.

In 21 Projectors (1967) the audience was surrounded with a staccato barrage of multiple film and slide projections in complex split-second patterns designed to reveal the surrealism of life in the media-saturated 1960’s. He describes his archetypal work as one in which “events on the screen and the actions of the audience merge: life becomes a labyrinth.”

1 Susan Sontag, “Film and Theatre,” Tulane Drama Review (Fall, 1966), pp. 24-37.