Associate Professor John Bradley is Director of the Centre for Indigenous Studies at Monash University. He has been actively involved in issues associated with Indigenous Natural and Cultural Resource Management for 30 years. The majority of this research has been undertaken in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria in the Northern Territory with particular emphasis on the marine and island environments of the Sir Edward Pellew Group of Islands, the country of the Yanyuwa people, Borroloola. His most important contributions to this field have been in regard to ethno-biology, Indigenous language maintenance, land and sea rights and documenting Indigenous knowledge. His work and commitment in this area is on going and involves undertaking consultancies in regards to land and sea and cultural management and has most recently has involved the trialing of animation as an effective method of recording intangible heritage and as a teaching device within schools in regards to the cross generational transfer of knowledge. He speaks two Indigenous languages. He is presently rewriting the Yanyuwa encyclopaedic dictionary a work which has spanned 30 years. He has also played key roles in film making at Borroloola. His work has been documented in The Language Man (ABC-TV, 2008), and he has an on going involvement in the Yanyuwa animation project.

Graham Friday, from Borroloola, is a Yanyuwa elder of the Wuyaliya clan. He is also the head Yanyuwa ranger for the li-Anthawirriyarra Sea Rangers. He is active and determined in trying to demonstrate the value of Yanyuwa culture and country to a younger generation of Yanyuwa youth. He has been one of the key advisors in regard to the animation project.

Dr Amanda Kearney is a lecturer in the School of Social Sciences and International Studies at UNSW. Her doctoral research focused on Indigenous Australian cultural and social engagements with homelands, the politics of place and human relationships with powerful places over time. This, and her ongoing research has developed in working with Yanyuwa people, the Indigenous owners of land and sea in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria, Australia. Working with younger and older generations Amanda has sought to understand and document the terms of engagement and experience that inform a uniquely Yanyuwa way of experiencing the land and seascapes. Amanda continues to work with the Yanyuwa to investigate the complexities of their sea country and the important cultural terms on which they must be managed for future generations of Yanyuwa people. As an extension of this she is undertaking research in the areas of Indigenous knowledge and cross-generational knowledge transmission. By way of collaborative research, with the Yanyuwa community, Dr John Bradley (Monash University) and Tom Chandler (Monash University) Amanda is now working to consider the role of new animation technologies in the education of young Yanyuwa people.

Leonard Norman, from Borroloola, is a Yanyuwa elder of the Mambaliya-Wawukarriya clan. Leonard played key roles in the films Journey East (Buwarrala Akarriya) (1988) and Aeroplane Dance (Ka-wayawayama) (1994), and has been another of the key advisors in regards to the animation project. He is also a ranger with the li-Anthawirriyarra Sea Ranger and sees an important part of his role in the education of youth in regard to their sea culture history and Law of Yanyuwa country.

In June of 2010 a senior Yanyuwa elder died. He was 75 years old. In all of those 75 years, he never left his country; he spoke Yanyuwa language “like the old people long dead”, he knew the Law of the country, and yet could also speak with authority in English to the many research scientists, Government officials and others who travelled across his country. Because of his great wealth of knowledge and formidable intellect, this man was respected widely. With his death, the Yanyuwa have lost “the book and volume of his brain” (Evans 2010: 9). A library has gone from the country of the Yanyuwa people.

This old man died as four Yanyuwa elders were preparing to board a plane from Darwin to Melbourne to attend U-matic to Youtube. These four elders, Dinah Norman, Mavis Timothy, Graham Friday and Leonard Norman, were to present film and animation projects and works that they have undertaken and produced over the last thirty years. Their travel to Melbourne was motivated by the desire to showcase the work that has been done to document and look after their Law and culture for present and future generations of Yanyuwa.

With the news of the old man’s death, this group of elders had to return to their home community of Borroloola, which lies 1000 kilometres south east of Darwin in the Northern Territory. Before leaving, they gave instructions to the Symposium organisers that the animations and films representing thirty years of their lives and history should be shown, even in their absence. The job of introducing the animations and films and speaking to their history and creation fell to a group of four people nominated by the Yanyuwa elders. These four people are not Yanyuwa, they are not Indigenous. Two of them are well known to Yanyuwa families, and two have a particular closeness to Yanyuwa country and some of its Law, as a result of working to produce a series of digital animations of Yanyuwa country, stories and Law. These four people are John Bradley, Amanda Kearney, Tom Chandler and Brent McKee.

The paper that was presented at the Symposium, in the form of an open discussion and question-and-answer time, provided some background commentary to the Yanyuwa animation project which began in 2007. The discussion was shaped not only in terms of an academic engagement but also the cultural place and value of the animations, facilitated by the words of Yanyuwa elders conveyed to Bradley and Kearney. This two-way conversation about the Yanyuwa animation project began when the first animation was shown to Yanyuwa families three years ago. We start here with Yanyuwa words, Yanyuwa voices and family sentiment in regards to the animations themselves and the sharing of these cultural expressions of Law and family at the ACMI event in April of 2010.

In a conversation that took place before the ACMI event, and later out on the islands of Yanyuwa country in the south west Gulf of Carpentaria, Graham Friday (a senior Yanyuwa elder) reflected on the animations and the public event:

You know we were really no good when that old man died, we could not come to Melbourne so what could we do? We had to go back down the long road to Borroloola, to our family and look after them. Those animations are our Law, Yanyuwa Law; it is not Law for any other group of people in Australia, no one else. Our old people are dying, they have died too quick, so we had to think of ways to teach our kids so they can know something about their country. We are really happy for these animations, young people, old people, we really like them. Let me tell you, people on the outside looking at them, people on the outside, “whitefellas or blackfellas” they have nothing to say, nothing at all, those animations, well, that’s the choice we make, we have to do what we can, we do not want our kids to sit around with nothing.

These sentiments were echoed by Dinah Norman, the 75-year-old matriarch of the Yanyuwa community. Sitting on her front verandah in the remote township of Borroloola (Northern Territory), surrounded by her grandchildren and great-grandchildren, Dinah spoke with Bradley, Kearney and McKee. She reflected:

I sit here and I look at these young people, all of them, my grandchildren and all these other children, they do not speak Yanyuwa, they do not hear Yanyuwa, they have not seen the ceremonies of the old people, they do not know, they are in ignorance of all these things, some of them know the country because their parents and grandparents take them, but still they do not know the Law, the Law from the old people. I sit with my grandchildren and I look at the stories [animations] on TV, I am so happy that they are there, I teach my children the Law from the country when they are watching, we are talking about the country and family, maybe, maybe they will learn some of the stories, a little bit of the Law. (Translated from Yanyuwa into English by Bradley)

Dinah Norman’s son Leonard was present when his mother spoke these words, and he followed up by saying:

We couldn’t come to Melbourne, we had all the family to worry about, you know that old man was a big man, a Law man, Anthawirriyarra wirdiwalangu [a knowledgeable elder whose spirit and Law has come from the sea], a saltwater man, you know. So we had to have respect for him. You know, we had to leave you [Bradley], Amanda and Brent to be there alone, to talk for the animations, that’s not really the way it should have been, but that old man …You know those animations are really important to us Yanyuwa people, they are helping to keep our country strong, as kardirdi [mother’s brother] Graham said we are making our own choices about how to teach kids, we have known you [Bradley] for many years and Amanda too we know her, you have worked with the old people, and we know Brent, and his work is really important to us, we make our own choices about these things, I am telling you, no one, not one European or Aboriginal has anything to say about this, we make choices, if they are right or wrong we make them.

The distress caused by the old man’s death and the great burden carried by elders faced with a reality of language loss, and a breakdown in understandings of Law amongst young people, echoes through the statements made by Graham, Dinah and Leonard. Their comments reveal the great burden of responsibility that they face in safeguarding their Law and culture. It is in this context that people make decisions and activate choices as to the best ways to maintain Law and culture for their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The fact that Yanyuwa families make choices that involve collaborations and creative projects involving non-Yanyuwa and non-Indigenous people is historically embedded in a tradition of cross-cultural relationships that are built upon a principle of great mutual respect.

Yanyuwa country was settled by Europeans as late as 1886, and its culture recorded in minor detail in 1901 by ethnographers Spencer and Gillen (1912; 1969). Detailed research on the culture as an autochthonous people with a unique language, epistemology and spirituality started only in the 1980s, at which point Yanyuwa people, long inured to non-Indigenous disruption of their culture and lifestyles, were intent on, and able to control, how they were represented. This was both empowering and threatening, as the mediation they engaged in by creating films, television programs, dictionaries, books and a website were necessarily conducted in English and by a dwindling team of culturally knowledgeable elders. Only two outsiders, Bradley and linguist Jean Kirton, learnt the language. Yanyuwa ventures into Western media and forms of expression were designed for their own children, and those outsiders respectful of the power of Law and culture, in the fervent hope that they could document powerful knowledge before it was too late, and archive it for future unimaginable uses by their own people.

Australians have slowly learnt, guided by the artists, how to read the publicly available spiritual content of these works, and to respect what is silently withheld from outsider scrutiny. The affect inhering in such works is palpable; it speaks in many voices, almost effortlessly, across the cultural divide. Such works are a splendid starting point for understanding Aboriginal culture in the classroom. Yanyuwa treasures, however, are linguistic – song poetry, oratory and ritual songlines, performance – rather than visual. However, in the last ten years, a rich painted art tradition has emerged amongst some Yanyuwa families as a mode of expressing ancestral and post-contact narratives associated with Yanyuwa country. It is indeed a more challenging exercise to foster understanding of affect using such resources which do not readily translate into Western media – and that is precisely the challenge that was faced at the ACMI event and which this discussion hopes to address.

The West has a long and inglorious history of dismissing Indigenous social formations and the moral orders that go with them, relinquishing them to the categories of traditionalism or nativism leftover from an undesirable past. Indigenous social formations have proven to be incredibly resilient across time, despite attempts at cultural annihilation by the West. Across the country, Indigenous people have managed to maintain some form of extended kinship network that forms the basis of their identity. The onus remains on the settler state to learn to appreciate, work with and accommodate these social formations, rather than trying to wish them out of existence. This is imperative because of the richness and complexity that characterises Indigenous social formations; and (in our case) because the Yanyuwa worldview has much to offer the West in terms of deep ecological knowledge, spirituality and ways of relating to the world around us.

What is very rarely fully appreciated in everyday Australian contexts is how Indigenous networks of kinship, and the affective ties they bring, are often made invisible by the academic and Governmental processes which draw out of this complexity essentialised understandings of Aboriginality and “Indigenous affairs”. This leads to a myth of “pan-Aboriginality” where the specificity of Indigenous cultural expressions, group politics, discrete languages and political histories are overlooked and undervalued.

Beyond this, Yanyuwa ways of knowing are not museum pieces; they are not relics of a former cultural order. Yanyuwa culture has changed and is changing in response to contact with the encroaching mainstream society. What have historically been compromised and remains threatened are levels of control over the processes of representation. Early colonial writing and ethnographic curiosity made many Indigenous Australians captives of the archives, powerless to control the means by which their cultures were represented or recorded. This remains a threat for Indigenous people in Australia, where the country’s Indigenous populations are invoked in mythical narratives for the purposes of tourism, political campaigning, policy development and international showcases (such as, for example, the Olympic Games in 2000). Yanyuwa (like many other Indigenous groups worldwide) are uncompromising in their desire to move beyond being prisoners of the archives, in order to determine and voice their aspirations for themselves – rather than to be spoken for by the state or academia.

Sadly, many senior members of the Yanyuwa community have passed away in the last decade. As a result, the community faces a crisis in the maintenance of Yanyuwa language and cultural expressions, and therefore the longheld means by which social formations and moral orders were constructed and presented across generations. In 1979 there were approximately 260 speakers of the Yanyuwa language (Bradley 1997, Bradley and Kearney 2008:12-16). Today, there are now only five semi- to full-time speakers, and they have for some time sought the means to record and share their language and Law in ways that are engaging and captivating for their children and young adolescents. The five remaining speakers face the daunting task of maintaining the language and developing educational programs within contexts of limited funding and training in language-maintenance strategies, and a mainstream schooling system that prioritises English in the classroom.

Today, the Yanyuwa population is made up almost entirely of middle and younger generations of people striving to find a place in the world, both as individuals and more importantly as Yanyuwa families with a shared and collective identity that is deeply embedded in social memory. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, in 2006 the Indigenous population of Borroloola (including the distinct language groups of Yanyuwa, Mara, Garrwa and Gudanji families) numbered 774 (see Australian Bureau of Statistic Census 2006). Of that total, the number of younger individuals within the age group of 5 to 24 was 249, whilst those aged 25-54 totalled 215 (see Australian Bureau of Statistic Census 2006). The median age of an Indigenous person in Borroloola is 21, identifying a young population that is in need of sophisticated and culturally appropriate education and knowledge exchange programs.

According to the census, the number of Indigenous elders (65+) in Borroloola, across all language groups, is 24. A small fraction of this includes Yanyuwa elders, for whom there is a sense of great urgency and concern over the transmission of cultural knowledge across generations. Ensuring the well-being of young Yanyuwa requires more than education, schooling and employment in non-Indigenous and mainstream terms. It requires a commitment to the nurturing and development of their Yanyuwaness, cultural awareness, political strength, pride and sense of self-worth. For elders, these aspirations can only be met if an intrinsic desire to know culture prevails and is fostered. Collaborative projects, such as the Yanyuwa animation project, were born of this intrinsic need.

The Yanyuwa animation project is best seen as part of a cumulative strategy that has been building since the 1980s, when Yanyuwa first started to engage in various forms of research and recording with linguists, anthropologists, archaeologists, ethnomusicologists, filmmakers, scientists and lawyers. To date, collaborations have included the documenting and drafting of a Yanyuwa dictionary (Bradley, Kirton and the Yanyuwa Community 1992), compilation of an Indigenous atlas detailing the intricacies of their homelands (Yanyuwa Families, Bradley and Cameron 2003), recording song and dance (Bradley and Mackinlay 2003, Mackinlay 1995, 2000), drafting and presenting land claim evidence (Bradley 1992), filming documentaries (Kanymarda Yuwa – Two Laws 1981, Buwarrala Akarriya – Journey East 1988, Ka-wayawayama – Aeroplane Dance 1992), establishing a community website (Diwurruwurru), and a junior Sea Ranger program in which young people are mentored in the cultural and scientific protocol for managing their homelands.

Drawing together Yanyuwa knowledge of Country and new technologies of audiovisual/digital representation represents a further evocation of Yanyuwa ancestral narratives as present memory. The animation project, presented at the ACMI event, involves the production of digital animations of ancestral narratives and songlines in both Yanyuwa and English language versions. To date a series of digital presentations of Yanyuwa ancestral narratives and songlines have been produced for Yanyuwa families, under their guidance and direction. Digital renderings of Yanyuwa Law allow a compression of time (ancestral knowledge/contemporary encounter) and space (bringing visuals and a sense of country to the television screen or computer) that results in a proximity and immediacy for young and old viewers in the moment of sitting down and watching the animations.

Yanyuwa cultural treasure, made up of a body of stories – some of which have associated song lines – were first systematically made available in print form in 1988 (Bradley) . This was achieved with an intersubjective methodology that saw Yanyuwa tell their ancestral story to John Bradley, who then drew what he was hearing, with guidance and reflection from the narrator and other family members who happened to be around. This subsequently became the basis for an increasingly sophisticated series of methods for recording Dreaming material. This bilingual, illustrated anthology was attentive to the site-specificity of Yanyuwa narratives and to the special significance of multiple sacred sites, some with particularly high affective charge. But like so many Western representations of mythological material, it was limited by its presentation in a particular form of media, namely a book, which restricts its potential readership to children with a proficiency in reading English, as well as literary and anthropological scholars with a particular interest in Indigenous knowledges. It has also been restricted in its capacity to tell the narratives of Yanyuwa country, in that this text has been delimited, defined and classified according to a restrictive Western definition of oral mythological narratives, including creation myths, legends of sun, moon and stars and animals, and moral tales.

Print representations of Yanyuwa narratives (and Indigenous narratives more generally) have several inherent limitations: they fail to distinguish between different kinds of oral storytelling practice, and mark whether the context is a storytelling session for children or adepts; or whether the version is a fully-fledged performance complete with archaic poetic language, music, dance, and perhaps intended for an audience restricted on gender lines. Most significantly, these narratives are often told in situ, with the part of the narrative relevant to a particular moment, locale or action. Context is a given and superfluous to the narrative, as the objects and places referred to are evident to a Yanyuwa auditor; the narrative may begin in media res as narrative elements relevant to place are foregrounded, and the continuities of those parts of the story that belong in other places (because in Yanyuwa, stories move across country) are left for another oration.

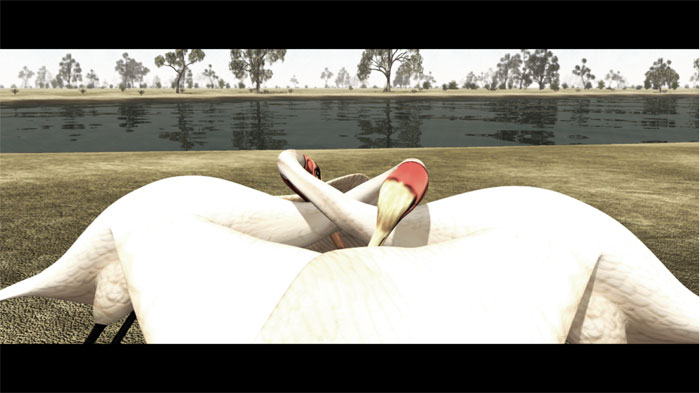

An excellent example of this is found in the story of the two Dugong Hunters Jurrunga and Jurruji (Figure 1). This particular narrative has been animated as part of the Yanyuwa animation project, and has been widely viewed and embraced by all generations of Yanyuwa families. This story is but one small part of a larger narrative that travels in an east to west direction across the breadth of Yanyuwa sea country (known today as the Sir Edward Pellew Islands). The portion of the narrative that has been enshrined in the animation, takes place on White Craggy Island, Wardirrila, and speaks to localised events at these places, whilst eluding to and making powerful reference to the extent of the story’s journey far and wide from the east to the west of Yanyuwa county.

The sense of the centrality of place to narrative is easily occluded in print texts, and very few anthologies of Indigenous Dreaming narratives pay any attention at all to this central element. Another element not deeply appreciated in Western re-presentations of Indigenous Dreaming narratives is that orations and songs are owned by those with a claim to the particular parcels of land spoken about or sung in the narrative – a notion that is anathema in the West where knowledge is considered freely available to those who seek it. Furthermore, European tales for children frequently get reduced to “just-so”, moralising tales. By contrast, Yanyuwa Dreaming narratives typically have cross-age auditors, many of whom are adepts not “spoken down to”. The narratives perform a great variety of functions from articulating the sacredness of the web of life, the kin relationships between the human and more-than-human worlds, to more mundane purposes like demonstrating how one might recognise a hidden water source, or know how to detoxify poisonous plants and render them nutritious. In other words, real learning through narrative and song is an expression of deep kinship ties, and can be location-specific. 120 years after white contact, these narratives inevitably carry a political freight palpable to their owners, and speak to a history of deep colonisation, dispossession and despoliation of sacred places by post-contact land use practices such as grazing and mining interests.

The Yanyuwa animation memory project is committed to moving away from crystallising manifestations of cultural expression, instead aiming to reproduce, with integrity, the vitality and affect of Yanyuwa narrative. The animations stand before generations of young people as aspirational motivators for finding and anchoring identity. They are dynamic constructions based on knowledge that is held by elders of the community who have a responsibility to make them present for younger generations. This younger generation carries the burden of stepping up as future elders and leaders equipped with the knowledge to manage, care for and carry country, Law and some semblance of a Yanyuwa way. The burden for both elders and younger members of the community is profound. Through decision-making processes, the Yanyuwa, in conjunction with anthropologists, digital animators and information technology specialists, have found a suite of mechanisms to illustrate ancestral beginnings in a manner that honours their ongoing presence in country.

Whilst elders are in a position of remembering and can call into being a social memory of Yanyuwa culture, middle and younger generations of Yanyuwa are not always equipped with an established knowledge of language and ancestral narrative. It is imperative that this knowledge, in some form or another, be present when younger people are in a position to seek it. The Yanyuwa animation project is an exercise in ensuring that the knowledge is present and available in generationally relative formats for young people to grasp it when ready. The transmission of an understanding of Yanyuwa Law and culture is considered a vital step in the development of self-esteem and well-being among younger generations who, according to elders, lack a sense of what it means to be a proper “Yanyuwa person” in the world today. For Yanyuwa elders, sharing of and looking after cultural information must take place in settings where the integrity of the knowledge is acknowledged, where there exists the social, cultural, political and emotional supports to fully understand what is encountered. Conscious decisions are made as to whether these supports exist.

Similarly, for young Yanyuwa, knowledge must be present in a manner that speaks to them, that resonates with the world that they know. It is in response to such a reality that Yanyuwa families have undertaken projects aimed at bridging gaps in knowledge and encouraging the cross-generational transmission of Yanyuwa culture. These are considered pivotal in the construction of mainstream and culture-based educational programs to teach younger generations of Yanyuwa just what it means to be li-Anthawirriyarra. In a world where Yanyuwa elders often feel that “things move too fast” and cannot contain the power of Yanyuwa narrative, the youth want access to their culture on terms that appeal to their generation. The terms of engagement and knowledge acquisition are heavily dependant upon, and influenced by, the desire to know, and having the conditions to support forms of knowledge in a shifting world of meaning – or at least to find connectivity between new knowledge and existing knowledge. For young and old, all exchange of cultural information is prefaced by the question: “What is the place for this knowledge?”

The completed works comprise a set of seven of digital animations (five stories and two partial songlines). They offer what print and web-based recordings of Yanyuwa Law and culture cannot. They capitalise on the highly visually literate X and Y generations, and on the new capabilities of 3-D animation, offering faithful recreations of actual Yanyuwa landscapes, peopled with realistic creatures. The landscapes have been built from a combination of satellite, photographic images and site-specific sketches, laying out the many landscape forms that exist in Yanyuwa country, and their surprising variety. For the non-Yanyuwa viewer who knows this country simply as “dry sclerophyll savannah”, the depiction of mangrove, ant-hill plains, rocky escarpments, islands, lagoons and lightly forested plains, all with their own distinctive moving Dreamings and geo-political and geo-physical land unit designations, indicate a different way of being in place, a greater intimacy in the encounter with the world around.

The animations allow the possibility that the sacralised transformation from vital to supervital be marked visually, non-naturalistically and dynamically, for example as in the Manankurra song line of the Tiger Shark, with bursts of light that viewers come to read as a marker of power. In Yanyuwa, such power is called wirrimalaru and it became important for a number of now deceased Yanyuwa elders that somehow this power be made visible. The team of animators and anthropologist/artist has generated a range of creatures in highly realistic detail that move and act according to each animal’s nature (yaynyngka or yaynyka in Yanyuwa). For example, in the case of the Brolga (Kulyukulyu) animation, the dancing brolgas – a long-legged bird found in savannah grasslands – acquire an extra charge for Yanyuwa viewers because of the fact that the much-loved ritual of the Brolga Dreaming, Kulyukulyu, was once used for funeral ceremonies as a way of returning the spirits of deceased kin back to their country (see Figure 2). What captures Yanyuwa affective responses is the memory of the ceremony and strong feelings evoked by the song and dance. For non-Yanyuwa viewers, the sheer aesthetic beauty of the images and the dancing movements will have their own pay-off.

The animations are challenging even for those who know the Country they animate. For insiders, cognitive dissonance occurs because the notion of story being intimately bound up with place has not been challenged by millennia of print and by the traditions of building-in descriptions of place, or by the narrative conventions of canonicity and breach (Bruner). A good example of the latter is the Wurdaliya narrative of the Farting Old Ngabaya (Spirit Man) (Yanyuwa Families et al. 2003:163-167) (see Figure 3). For a non-Indigenous reader of the tale, it has very little semantic coherence and no narrative impetus. It lists names of sacred sites in the order they are visited by Dreamings and briefly details their uses, tells of Dreaming creatures and pathways in the area, of initiation and funeral ceremonies conducted in the immensely long (25 kilometre) sand hills between the Robinson River mouth and Sandy Head, and of quarrels among groups of spirit men which result in the leader emitting a fiery fart which kills the dissidents. A diligent Yanyuwa insider who does not know the territory or an earnest outsider could consult the Atlas glosses (Yanyuwa Families et al. 2003:165-167) to the story, maps and photographs and learn a great deal more that would be of academic interest. However, how the digital animation adds affective value is to convey the urgency of the debates through tone of voice, to show the country in the almost photographic detail that the print story simply does not encompass, and to show the transformations in action.

One becomes aware of the resources of this Country (and their limitations) through the engaging graphics and its sacred resonances, especially when one witnesses the magical creation of sunken Pandanus tree circles that harbour wooden log-burial coffins. The sinister, blank but glowing eyes and huge feet and hands of the unpredictably powerful Ngabaya men, and their internal querulousness, function at many levels – reinforcing taboos about who may and may not be in the territory, how groups ought to conduct themselves (especially in relation to food and negotiations), and why these places are private and significant. For insiders, the images undoubtedly evoke memories of the ancestors, Dreaming and otherwise, who have been familiar with these places. The intensity of the old man’s fart and its consequences dramatise and enact sacred power, its terror, and the legitimacy of experience of the Country and kinship with it.

Traditional oral cultures and new technologies of digital media are underwritten by different imperatives and, for the West, there is the ever-present colonialist dilemma of the risks of commodifying, exoticising and othering cultural groups and their knowledges. The non-Yanyuwa learner inevitably relies on his/her cultural paradigms, needing reassurance that the journey is productive and mutually illuminating. The journey here outlined, the creation of the Yanyuwa animation project, has led to Yanyuwa families finding new and more effective ways of communicating their Dreaming narratives and their affective ties to kin, country and Law. This has been, and remains, an energising multidisciplinary and bicultural framework in which Indigenous and non-Indigenous people came together to achieve something that they each thought was important and meaningful.

This is a project with huge educational potential, not only for understanding the Dreaming narratives themselves, but also for cross-cultural exchange of a truly postcolonial kind. What the stories potentially teach a non-Yanyuwa listener/viewer is the difference between Western “hearings” of stories and Yanyuwa ontology. The beginning of this understanding is country, not imagined but actual, with its embedded affect, which is then overlain with kinship, an even more intense affect which connects people and all aspects of their world – other people, places, ancestors, spirits, country, animals, elements, and so on.

Each of the Yanyuwa cultural recording projects undertaken over the last few decades – including the books, dictionary, website, visual atlas, and the animations – are testament to cultural survival in very real terms. Furthermore, they enact crucial postcolonial and trans-cultural conversations that involve nothing less than understanding that all knowledge systems are necessarily provisional and dynamic, and mutually enriching. From a discussion of these various media and their uses for Yanyuwa and outsider education, there emerges a dynamic decolonising tension that warrants active acknowledgement. This springs forth from the different teaching and learning constituencies that create and then encounter Yanyuwa cultural recordings and presentations. In fact, the Yanyuwa animation project is an excellent starting point to teach decolonising methods and theory to a wide audience of non-Indigenous people. The specifics of this audience remain to be seen, as presently the animations have been created only for Yanyuwa families who are nurturing this body of knowledge in the quest for cross-generational knowledge transfer.

Amongst the elders Dinah Norman, Graham Friday, Mavis Timothy and Leonard Norman, and their extended family groups, a discussion is taking place as to where the animation project goes from this point. At invitation, Bradley, Kearney, McKee and Chandler are welcomed into these discussions to offer what they may to the ongoing effort of safeguarding powerful Yanyuwa knowledge for generations of young people that will stand up strong in their country and remember the lives, stories, affection and love of their old people. These are the choices that Yanyuwa make.

This paper is dedicated to Yanyuwa elders who are no longer with us, but spent their lives teaching the power and value of their land. In particular, this paper is dedicated to two Yanyuwa elders, Annie Karrakayn and Steve Johnston, who were instrumental in helping develop the storyboards and conceptual layout for the animations. This paper is also dedicated to the Yanyuwa youth who, through the animations, begin to see and feel more clearly their old peoples’ inheritance.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistic Census 2006. Available at:

http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/d3310114.nsf/home/Census+data. Accessed February 1, 2008.

Bradley, J. 1988. Yanyuwa Country: the Yanyuwa People of Borroloola Tell the History of Their Land. Richmond: Greenhouse.

Bradley, J. 1992. Warnarrwarnarr-Barranyi (Borroloola 2) Land Claim. Anthropologist Report on Behalf of the Claimants. Darwin: Northern Land Council.

Bradley, J. 1997. ‘LI-ANTHAWIRRIYARRA, People of the Sea: Yanyuwa relations with their maritime environment’, PhD Dissertation, Northern Territory University, Australia.

Bradley, J. 2007. Personal Communications, December.

Bradley, J., J, Kirton and the Yanyuwa Community. 1992. Yanyuwa Wuka: Language from

Yanyuwa Country, a Yanyuwa Dictionary and Cultural Resource. Unpublished document.

Bradley, J., and A, Kearney. 2008. Report on Remote Learning Partnership Project:

Borroloola Community. Consultancy Report to the Northern Territory Department of

Employment, Education and Training.

Bradley, J., and E, Mackinlay. 2003. “Of Mermaids and Spirit Men: Complexities in

Categorisation of Two Aboriginal Dance Performances at Borroloola, Northern Territory”,

The Asian Pacific Journal of Anthropology 4.1:1-23.

Evans, N. Dying Words. Endangered Languages and What They Have To Tell Us. London: Wiley-Blackwell.

Mackinlay, E. 1995. “‘Im Been Dance La Me!’: Yanyuwa Women’s Song Creation of the

Northern Territory”. Australian Women’s Composing Festival. Sydney: Australian Music Centre.

Mackinlay, E. 2000. “Blurring Boundaries Between Restricted and Unrestricted Performance:

A Case Study of the Mermaid Song of Yanyuwa Women of Borroloola”. The Pacific Journal of Research into Contemporary Music and Popular Culture 4.4:73-84.

Spencer, B., and F. J. Gillen, 1969. The Northern Tribes of Central Australia. Oosterhout: Anthropological Publications.

Spencer, B., and F. J. Gillen. 1912. Across Australia. Vols 1 and 2. London: MacMillan.

Yanyuwa Families, J., Bradley and N, Cameron. 2003. Forget About Flinders: An Indigenous

Atlas of the Southwest Gulf of Carpentaria. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Yanyuwa Families, J., Bradley, A., Kearney, B., McKee, T., Chandler, and C., Ung. 2009.

Wirdiwalangu Mayangku kulu Anthawirriyarrau – The Law that comes from the Land, the Islands and the Sea. (DVD) Monash University: Digital Animation Project.

Including the following ancestral narratives:

Crow and Chicken Hawk – Malarrkarrka kulu a-Wangka,

Brolga – Kurdarrku,

Dugong Hunters – li-Maramaranja,

Spirit Man – Ngabaya,

Tiger Shark – Adumu,

Rainbow Serpent – Bujimala

Manankurra songline part 1 and part 2.

Films

Two Laws (Kanymarda Yuwa). 1981. Directed by the Borroloola Aboriginal Community, with

Carolyn Strachan and Alessandro Cavadini. Red Dirt Films.

Journey East (Buwarrala Akarriya). 1989. Directed by Yanyuwa community, with Jan Wositzky. Marndaa Films.

Aeroplane Dance (Ka-wayawayama).1994. Directed by Trevor Graham. Film Victoria.