You Can’t Keep A Good Auteur Down

This article was originally published in The Chicago Reader 23 August 1974. It is published here with the kind permission of the author.

Most of the people I know don’t seem to like Julie Andrew’s too much. And so, I suppose that most of the people I know aren’t going to like The Tamarind Seed, Blake Edwards’ new film, just because he’s indulged himself in a little nepotism and cast his wife, sweet Julie herself, in the lead. Now, ask yourself, is this a responsible attitude? Is this any way for your average, young, affluent, and college-educated moviegoer to conduct himself? Is it right to harbour a bitter resentment toward a well-meaning person who you’ve never even met just because one rainy evening in 1965 your parents dragged you kicking and screaming to the local movie house where you were forced to endure The Sound of Music, possible the most puerile picture ever made, and all because your mother thought the family should “do something together” for a change? Just because you would have rather stayed home to watch The Man from U.N.C.L.E, does that make it right for you to hold a grudge against an innocent woman for ten whole years, to the point where you felt secretly revenged when you heard that The Julie Andrews Show had been cancelled in midseason last year? Well, maybe. But that still doesn’t stop The Tamarind Seed from being one of the most intelligently written and directed films to come along this year (would I kid you?)

Blake Edwards has come a long way since he was the toast of Hollywood in the early sixties. His nearly unbroken chain of commercial and critical successes (from Breakfast at Tiffany’s through to The Pink Panther) was beginning to rust a little when he made The Great Race, his first overbudgeted superproduction, in 1965. From that point on, Edwards’ films became more idiosyncratic and less profitable, and his stock reached the low point in 1969 with the financial disaster of Darling Lili. Even though was easily the best musical of the sixties, nobody seemed to take to this World War I extravaganza featuring Julie Andrews as a Mata Hari type desperate to bed down with flight commander Rock Hudson. It was too bad, since the film cost about $15 million (according to rumour), and when it grossed something like a buck and a half on release, Paramount Pictures nearly took the pipes. Edwards’ last two film Wild Rovers and The Carey Treatment, were made and unmade at MGM, where studio chief James Aubrey went ape with his notorious executive scissors in attempts to make the projects more marketable, and succeeded only in making them nearly incoherent. You can’t keep a good auteur down, though, and now that Blake is back with the blessing of independent financing, it’s clear that his abilities are as sharp as ever.

Edwards’ characters usually inhabit closed, hostile environments from which they can rarely escape and must eventually become a part of. The setting of most of the comedies and mainly of the dramas is the sleek superficial world of a sophisticated urban society. The idea of superficiality plays an important part in Edwards’ mise-en-scene, as he generally uses the glossy surfaces, bright colours, and hard lines of the harsh architecture that surrounds his characters to define them. In Gunn, probably Edwards’ most explicit film, the repetition of these elements equates the hero’s expensive Bel Air home to a succession of night clubs and bars, and finally to a run down seaside carnival. It’s as if the nightmare world that Hitchcock’s characters suddenly find themselves in is a given for Edwards instead of a potential. We’re born into hell, we don’t fall there anymore. The inescapable malignant force that forms the cold geometry of Edwards’ images precludes the possibility of compromise, and so if a character is to function at all within those images he must become as impersonal as they are. Communication then becomes reduced to ritual.

Edwards, though, is a fervent moralist. His heroes possess a surprising degree of moral force which they attempt to sublimate in order to deal with the decadence of their surroundings, until like the James Coburn character in The Carey Treatment, that force erupts in the face of some particular outrage. To the other characters the hero’s actions seem insane, suicidal. Peter Sellers’ Inspector Clouseau appears as a destructive bungler in the world of The Pink Panther and A Shot in the Dark precisely because he is the only character in those films with any degree of ethical awareness.

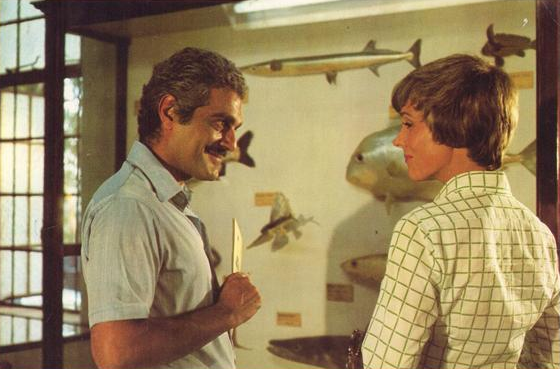

In The Tamarind Seed, the place of moral outrage is superceded by romantic love. Andrews is a secretary to a high British government official who falls in love with Omar Sharif while she is vacationing in the Barbados. Sharif, though, turns out to be a Russian spy, and while Julie doesn’t mind, their superiors back in London take a dim view of the situation. The affair sets off an incredibly complicated string of events which culminates in Sharif’s exposure of a traitor in the British defence department in exchange for political asylum.

Edwards uses the London/Barados dichotomy to underline the basic conflict in this film between the corruption and inhumanity of the men involved in the rival intelligence organizations and the purity and immediacy of Andrews and Sharif’s relationship. The film ends on a bravura play on Edwards’ part that sure to alienate middle brow audiences from coast to coast. While the stars are hiding from the secret police in a Barbados beach bungalow, a bomb explodes, maiming Andrews and apparently killing Sharif. Andrews is recuperating in a local hospital when the head of the English intelligence service arrives with an envelope for her. Inside is the tamarind seed telling her that Sharif is still alive. The ending, which at first seems totally contrived, works when we realise how subtly Edwards has built up the seed as a symbol. According to island legend, the seeds of a tamarind tree at a certain plantation took on the shape of a man’s head after the tree served for the lynching of a slave. Sharif cynically scoffs at the story (at this point, he still belongs to London) when Andrews shows such a seed at the local museum. Later, Andrews must leave the island to return to her job. As she boards the plane, Sharf gives her a package in which she finds a seed like the one on exhibit. Sharif’s acceptance of the seed as a symbol of a miraculous sympathy between man and nature reflects his regeneration through his relationship with Andrews. The seed’s reappearance in connection with Sharif’s resurrection characterizes that event as a genuine miracle. Their relationship, which first offers them the hope of survival in the brutal world the film portrays, finally allows them to transcend that world completely in some quasi-religious sense. The lovers are re-united in a remote, apparently unpopulated valley, a setting which suggests a realm of experience entirely different from any that the film has presented before.

The Tamarind Seed may not be everybody’s cup of tea, to say the least, but I think even the most cynically minded viewer would have to begrudge Edwards some respect for the conviction that he brings to his admittedly unfashionable material. It takes a lot of nerve to throw logic of your narrative out the window in favour of a more personal ending, but Edwards has never shown himself willing to compromise.

Cruel To Be Kind

This article was originally published in The Chicago Reader 17 July 1981. It is published here with the kind permission of the author.

Blake Edwards’s S.O.B. has been received as a fierce farce in the tradition of Swift and Waugh, but what impressed me most was its ultimate lack of corrosion. Again and again, Edwards sets up a sequence for a smashing satiric blow, but just as the hammer is whistling down, it disappears; a tap of compassion appears in its place. S.O.B. is an angry film, but not a bitter, annihilating one, for all of it’s emphasis on the grotesque, the vulgar, and the venal, it leaves a sense of emotional generosity in the end—if not compassion, understanding; if not forgiveness, acceptance. Unlike Swift and Waugh—and unlike Robert Aldrich, whose chilling Hollywood satire, The Legend of Lylah Clare, genuinely belongs to their tradition—Blake Edwards is not a misanthrophe. He doesn’t have the scornful distance of the true satirist; the rhetoric of contempt, of absolute, icy separation from his characters, and their situations, isn’t his. He has, of course, implicated himself in his satire: S.O.B. is about an attempt to rescue a commercially suspect film through the surprisingly crass ploy of baring the breast of its goody-goody star, a strategy indistinguishable from the marketing plan for S.O.B. The affronts deployed in S.O.B. are largely affronts committed by S.O.B. But Edwards’s involvement goes beyond autobiography and simple self-laceration. As a filmmaker who has always urged his audience to see through surfaces and penetrate the emotional truth underneath, Edwards is incapable of adhering to a strict surface view of his characters, which may be the chief stylistic requirement of satire. The two-dimensional caricatures of S.O.B. have a disturbing tendency—the process seems almost subconscious—to turn into three-dimensional characters. It’s not a matter of thick “humanizing” touches applied here and there, discretely labeled virtues to balance out the vices, but of an attitude that comes from behind the camera, expressed through the length and composition of shots. There is a remarkable moment, for example, when Shelley Winters, playing a greedy, treacherous talent agent in her standard cartoon style, is discovered sharing a bed with a black woman. What begins as a vaguely racist, certainly sexist shock gag develops into a valid, broadening character point about Winters, largely because Edwards does not cut away from the black woman immediately after getting his laugh. Instead, the shot persists (Winters is talking on the telephone), holding both women in a loose comfortable, wide-screen composition, and the persistence gives the black woman some weight, some independent presence. She’s there as an answer to Winters’s emotional needs (sad needs, if the woman is a prostitute), and she lets us see a side of Winters that we hadn’t expected: the harridan has a heart. It’s a small moment, but a very revealing one, pinpointing the qualities that set Edwards apart from most contemporary comedy directors. In Mel Brooks’s movies, people are turned into jokes. In Edwards’s, jokes become people.

In S.O.B., Blake Edwards set out to make a stinging, acidulous satire, but I think his best instincts as an artist got in his way. The film fails as satire, but it fails in ways that are consistently more interesting, more complex, than the effects he seems to be aiming for. It’s as if Edwards wrote one movie and directed another: the verbal clues to the characters to the characters, which are deliberately vulgar, heavy, cheap, don’t jibe with the dimensionality, the vulnerability, and (occasionally) the courage with which the actors move through the frame. I’ve been told that the script for S.O.B. was written in the early ‘70s (it took Edwards success with 10 to get the project off the ground); perhaps he’s lost the edge of his anger in the intervening years. The only thoroughly black character is the studio chief played by Robert Vaughan (his name is David Blackman, and he dresses entirely in black), who is an amalgam of the heads of Paramount and MGM when Edwards worked for those studios during his darkest days. For the first half of the ‘70s, it seemed that no Edwards film could be released without being subjected to commercial “improvement”, and when Edwards has Blackman boast to his lackeys, “If there’s one thing I am, it’s a great cutter”, the line has the anger of an artist attacked where it hurts the most—in the mutilation of his work. Yet Edwards is able to muster some sympathy for Blackman, if only as a cuckold (his girlfriend is two-timing him with an actor, in a subplot based on a well-known Hollywood incident). And Vaughan is also allowed to give the wittiest (and least expected) performance in the picture: as he struts and strikes poses with the high physical stylization of a veteran farceur, you can’t help but warm to him; the charm and talent of the actor are permitted to shine through the character. Even David Blackman, after all, is only doing his shoddy best under impossible circumstances. And so goes S.O.B., devoted to a tremulous sense of shared humanity and institutionalized madness, a devotion that emerges almost in spite of its author.

When Edwards was in his first ascendancy during the early ‘60s, he was often attacked for the savagery of his gags—for the cruelty of the bedroom farce in The Pink Panther, the too-realistic deaths in A Shot in the Dark, the sheer excess and frenzy of the pie fight in The Great Race. Edwards was widely credited with being the first filmmaker to embrace the sick-joke aesthetic of Lenny Bruce and his nightclub followers. Yet the sick joke, as perpetrated by Bruce, hangs on a purposeful repression of feeling, a fierce denial of humanity as a means of coping with an inhuman world. Edwards’s gags were (and are) cruel, but what distinguished them from the sick joke was Edwards’s constant insistence on the consequences of his gags, on pain. Characters who catch their fingers in cigar cutters appear in subsequent scenes with bandaged hands: Edwards seldom grants his characters the powers of instant healing that are routinely given in cartoons and classical slapstick. The sting of pain is a quality unique to Edwards’s sight gags, and it gives his gags a unique emotional complexity—something of a distorting mirror effect, in which every laugh bounces back as a grimace, every comic cruelty is answered by a pang of compassion. Edwards insists on pain in his humour, not as a sadist, but as a deeply committed humanist. It’s been said that, through pain, we learn we are alive: the same can be said of Edwards’s characters. It is through their pain that we approach them, know them, and it is often only in pain that Edwards’s characters achieve self-awareness—the knowledge that they exist, and that they hurt.

In a world so full of pain, both physical and emotional (in the comedies no less than in the dramas), there must be anesthetics—and Edwards’s are full of them” alcohol (chiefly in Days of Wine and Roses, but incidentally in almost every Edwards movie), drugs (The Carey Treatment), sexual obsession (10), and sarcasm (Edwards’s diagnosis of Los Angeles in Gunn is of a city suffering from terminal flipness). S.O.B. covers all of these, and adds some new ones, notably money (the single-minded pursuit of) and movies (the single-minded pursuit of). There are two poles of existence in Edwards’s film—agony and oblivion—and his characters constantly shuttle between them.

In S.O.B., Edwards goes further into oblivion than he has ever done before: it’s as if the Hollywood setting, a landscape of constant betrayal, demaned more and stronger drugs than any world Edwards has ever explored. His central character, producer-director (and autobiographical figure) Felix Farmer (Robert Mulligan), has, at most, three or four lucid moments in the entire film; the balance of the time he is drugged, suicidally depressed, or maniacally enraged (in the astonishing finale, he goes yet another step further). Even the structure and visual style conspire to keep Felix in a steady haze. Rather than organize the film around the acts and perceptions of his central character, as this kind of autobiographical fantasy would seem to invite, Edwards has divided his movie into three main sections, each presented through diffuse ensemble playing. The first section takes us from Felix’s suicide attempts upon his discovery that his multi-million dollar musical is a bomb through his hatching of a plan to save the film by giving it some sex; section two covers the making of the remake, from Felix’s scheme to buy the film back from his studio to the filming of his wife’s nude scene; th final sequence begins with Felix’s ultimate betrayal by the studio, and proceeds to a conclusion of surpassing strangeness and unexpected delicacy. Each section ends with a moment of breakthrough—a sudden parting of an anesthetic haze—but only the first belongs to Felix. For the balance of the film, he skulks, often unnoticed, through the foreground or background of Edwards’s elongated frames, frequently inscribing a straight, unruffled trajectory across the dramatic action that occupies the centre of the frame and involves him only tangentially. The crowding of the images—with a remarkable collection fo character actors—itself becomes a kind of haze, through which Felix’s blurry figure can occasionally be discerned. Edwards’s visual and narrative strategies inflict on Felix the ultimate Hollywood indignity: he isn’t allowed to star in the movie of his life. And this strange, insistent dislocation gives the film a curious, highly effective emotional spin: we have to fight to hear Felix above the din, and our efforts to make him out—to approach this clearly central character who is never allowed to occupy the centre—turn into metaphor. The chief concern of S.O.B. if not film colony satire, but a more universal emotional subject: the failure to connect, to be heard, to achieve an authentic moment within an artificial, anesthetized world.

Standing in opposition to S.O.B.’s crowded interiors—parties, sound-stages, offices—is the openness of the ocean: we glimpse it through the picture windows of Felix’s Malibu home; later it becomes the setting of the final sequence. Edwards has often used vast, natural elements as a rebuke to the haze of his characters—the Alpine slopes of The Pink Panther, the shifting landscapes of The Great Race, the sea and Hollywood Hills of 10. It’s an image distinguished less by it originality than by the subtlety and suppleness of its use; nature insinuates itself into Edwards’s films with a sanctified stealth. The opening shot of S.O.B. (following the satirical credit sequence) is of the ocean shore, an elderly man appears, jogging with his dog. He suffers a heart attack, and crumples to the sand—and the camera pans up from his body to Felix’s patio, where the director sits, stunned by the first news of his failure. The body on the beach, accompanied by the howling, mewing dog, becomes a running gag; days pass before anyone notices that he is dead, as the tide washes the corpse in and out. But the gag stops being funny after the first time or two that Edwards returns to it; instead it deepens in a way that seems emblematic of Edwards’s method in the film as a whole. What begins as an archetypal Edwards “sick joke” becomes something almost unbearably painful: the imagery of the sea, backed by the cries of the dog, whistles through the farce of the film like a cold wind. An intimation of mortality as strong and blunt as this has no place in a giddy Hollywood satire; it represents Edwards’s personal call to feeling, a call that can be heard in all of Edwards’s work, though seldom with such piercing urgency. That call makes S.O.B. a fine exemplar of an all but extinct tradition: the serious American comedy.