The image we make ourselves of history is, more than ever, shaped by the audiovisual record. But the documentary image and sound cannot provide a transparent view on reality; it represents a world by mediation through an interpretive act. Therefore the documentary film’s historical account requires a perceptual engagement that resists the pull of the indexical and views the audiovisual record as inscribed by the contexts that have brought it forth. The need for such critical engagement is perhaps never more acute than when its object is the representation of war, and thus moments of contestation over truths and rights.

Control Room (US, 2004) by Jehane Noujaim is an early example of a sizable number of documentaries on the Iraq War and its aftermath. It covers events from the initial deployment of the so-called “shock and awe” tactics in March 2003 to the breakdown of civil order in the wake of the fall of Baghdad six weeks later. However, it is not the war itself that Noujaim focuses on. Rather, she observes these events at a double remove: the film’s locations are CentCom, the US central military command and media hub in Doha, Qatar, and the nearby headquarters of the TV satellite channel AlJazeera. From these vantage points, she investigates the construction of competing versions of the Iraq War and the pressures that shape them.

The promotional tag which accompanied the release of Control Room, “Two Channels. Two Truths”, highlights the questions which the film raises about the correspondence between the war and its audiovisual representation. In staging her inquiry into this, Noujaim crucially draws on the integration of footage from media sources. This practise of re-contextualisation of audiovisual “ready-mades” invokes, as Stella Bruzzi notes, “the fundamental issue of documentary film” and thus “the way in which we are invited to access the ‘document’ or ‘record’ through representation or interpretation, to the extent that a piece of archival material becomes a mutable rather than a fixed point of reference”.[1]

Given the thematic concern of Noujaim’s film with the construction and constructedness of audiovisual records of the Iraq War, how does she, in turn, make fragments of these records contribute to the rhetorical project of her film? This is the central question which will be investigated.

Control Room – Introduction

The conditions which govern the representation of armed conflict were thrown into particularly sharp relief during the war in Iraq: it was marked by an unprecedented intensity of coverage as well as a new form of media management in the shape of the large-scale embedding of journalists: 628 correspondents from 262 media organizations reported in real-time as they lived and travelled with fighting units, and fed into a 24/7 rolling programme of TV news reporting.[2] Embedding seemed to provide unprecedented access to images from the frontline. However, it did so within a highly controlled environment that seemed to jeopardise journalistic independence and offered immediacy without context and overview. More conventional processes of media management by the military were also in force during the conflict. Embedding was complemented by daily briefings for the world’s media from CentCom. Pronouncements in the shape of a “Message of the Day” were delivered to the contingent of international correspondents. Unattached or “unilateral” journalists were discouraged from venturing into the war zone. Where journalists defied this injunction, they reported under the watchful eyes of Saddam Hussein’s information minister and were exposed to considerable risk of being caught-up in the fighting. As the Organisation Reporters Without Frontiers states: “The second U.S. war with Iraq has been the most lethal for journalists since World War II”.[3] According to figures published by this organisation, 12 journalists were killed in the two months following the invasion of Baghdad. Altogether, between March 2003 and August 2010, 172 journalists lost their lives. While foreign correspondents made up the majority of the early casualties, 87 per cent of the overall number of casualties were reported to be Iraqis.

All the above obstacles in the pursuance of truth are evident in Control Room: information-flows to journalists are carefully managed in military briefings. An extensive sequence shows the bombing raid on the AlJazeera headquarters in Baghdad. The live reporting as coalition force take Baghdad is shown to record a thoroughly stage-managed event.

The exigencies of war reporting evoke the discussions amongst the film’s characters. They revolve around the conflict between a professional codex of unbiased reporting, culturally inflected obligations to bear witness, and military priorities. Thus, senior AlJazeera producer Samir Khader opens the film with the statement that propaganda is an integral part of any military campaign. In the context of war, objectivity—as Joan Tucker, manageress of the English-speaking AlJazeera website states—is a mere “mirage”. In one exchange, a correspondent from Abu Dhabi Television articulates his conflict of loyalty between a professional ethos of detachment and his cultural allegiance as “my people are being killed in Iraq”. Different cultural horizons shape not only what is shown but also what is seen. In one scene, media analyst Abdallah Schleiffer explains to American Press Officer Lt. Josh Rushing, that for an Arabic viewer, images of European-looking soldiers in Iraq will simply “blend” with the well established iconography of Israeli soldiers in Gaza – a political and visual context of which Rushing deems the American public to be largely ignorant. Recurring reaction shots of the AlJazeera staff as they watch images of destruction, inscribe this theme into the film. Control Room points to the way in which ideological and cultural disparities materialise around institutional contestants in a war that is not least fought with images. On one side of this divide are the Western media, a tradition of freedom of the press and an established hegemony in reporting about the Middle East. The emergent contestant to this dominance is the leading Arabic-speaking TV satellite channel AlJazeera.

Noujaim’s dramatisation of different representations of war crucially draws on statements by, and discussions between, a recurring set of characters from both camps in this war over representation. All of these characters display a complexity that defies cultural stereotypes. Thus, senior AlJazeera producer Samir Khader attests a failure to embrace modernity and democracy to the Arab states. His pent-up anger about the US invasion does not prevent him from seeking to “exchange the Arab nightmare with the American Dream”. If offered a job with Fox NC, this astute observer of the manipulative use of the media confides, he would take it. Sudanese born Hassan Ibrahim, a former BBC journalist, states his belief that the American people will stop a foreign policy of which he is an acerbic critic. American press officer Lt. Josh Rushing exhibits a combination of spin, bewildered naiveté and an astonishingly frank inquisition of his and his peer group’s assumptions.[4] This set of central characters is complemented by various international correspondents and representatives of the army, who make a more intermittent appearance. Together, these are the film’s agents in the constant process of raising and addressing issues surrounding the nature of war-reporting from opposing perspectives. The film’s marked predominance of close-ups, which are often the result of zooms from medium or long shots, reflect the central function which Noujaim ascribes to her characters. This also, one might surmise, exercises a degree of visual scrutiny in the presentation of a set of media experts who talk about the media. In Noujaim’s own account, the perception of her small film crew as part of a student production encouraged a willingness to talk frankly.[5] Undoubtedly, the impression which is conveyed by each of these characters is, to quote Bill Nichols, that “of a complex persona, without suggesting that the persona is a role wholly distinct from the person they would normally represent”. [6]

Noujaim’s juxtaposition of two truths downplays authorial intervention both in the eschewal of a voice-over commentary and the masked interactions between the film team of two and the film’s characters. With the exception of one almost inaudible brief question, the presence of Noujaim’s film crew is effaced. Factual inter-titles structure an extended exposition which sets out the film’s narrative baseline and introduce us to the main characters. But this overt authorial commentary soon dwindles to captions with the name and function of characters, and rare instances of temporal or narrative anchorage. It is from a weave of materials and a more dispersed narrative agency that Noujaim’s rhetorical project emerges: using a familiar documentary formula she intercuts her characters’ present tense statements with filmed passages from CentCom and the Doha AlJazeera headquarters and news footage.

This revolves around two themes: in four appearances President George W. Bush comments on the start and progress of what would come to be known as the official phase of the war, and demands Iraqi reciprocation of the humane treatment of prisoners of war. Three interventions by Donald Rumsfeld level accusations of faked evidence, propaganda and outright lies against AlJazeera. This footage enlists official statements to establish the chronology of war as the film’s temporal background, but it also testifies to AlJazeera’s pursuance of its motto, “The Opinion and the Other Opinion”. Noujaim’s inclusion of news fragments which carry the AlJazeera logo and feature announcements by the channel’s most prominent detractor, Donald Rumsfeld, as they are being interpreted into Arabic, contributes not least to AlJazeera’s characterisation as a pluralistic platform for dissenting voices.

A second and more copious set of footage features images of war and its consequences. It records angry protests against the US invasion, passionate pleas by Iraqi civilian victims of the bombing, US prisoners of war, and casualties from both sides. An extended sequence is dedicated to the death of AlJazeera correspondent Tarek Ayoub and the popular outcry that followed the US attack on the AlJazeera headquarters, a location that had been previously identified to the military command by the channel. Images of the breakdown of civil order and looting follow the iconic footage of the fall of Saddam Hussein’s statue.

Representations of War – Framings and Re-appropriations

Shots of bombs raining down on Baghdad and tanks driving through the desert became familiar TV viewing during the Iraq War. However, the major part of Noujaim’s selection of footage reflects aspects of the war which some audiences would have seen little of. The well publicised controversy surrounding AlJazeera’s broadcasting of images of American prisoners of war and casualties, highlighted different framings of the conflict in Iraq. Aday’s comparative analyses of war reporting by five American channels and AlJazeera list these differences. He comes to the conclusion that:

the coverage was dominated by episodic battle coverage, which, while certainly being the most important daily story, ended up crowding out other important aspects of the war. For American viewers in particular, the portrait of war offered by the networks was a sanitized one free of bloodshed, dissent, and diplomacy but full of exciting weaponry, splashy graphics, and heroic soldiers. [7]

AlJazeera, by contrast, focused more extensively on issues such as diplomatic efforts at conflict resolution, anti-war protest and the casualties and victims of war. With its focus on what Samir Khader summarises as the ”human cost” of war, the selection of war footage in Control Room contests a “sanitized” version of the Iraq conflict.

The thematic focus of Control Room is, in the words of Judith Butler, the “frames of war”. The frame, she notes:

does not simply exhibit reality, but actively participates in a strategy of containment selectively producing and enforcing what will count as reality … Although framing cannot always contain what it seeks to make visible or readable, it remains structured by the aim of instrumentalizing certain versions of reality.[8]

In Noujaim’s film different accounts of the conflict are shown to be shaped by a “weave of limitations”. [9] Notions of truth, objectivity and evidence become a ground of contestation which is mapped out by the statements of the film’s characters.

The iconic footage of the raising of Saddam Hussein’s statue in Baghdad’s Firdous square sparks off the film’s most exemplary discussion about the evidential value of images. In this we see reporters as they rush alongside the advancing tanks with recording equipment for this real-time representation of the fall of Baghdad. AlJazeera staff dissect the image as a consummate enactment for the media: the readily available pre-1991 flag, the unlikely uniformity of age and gender and the nationality of the allegedly joyous crowd is called into question. While the cadrage of this event supports its interpretation as a spontaneous expression of joy, a wider angle shot shows that, contrary to official claims, the local population is not coming out in celebration (Figs. 1-2).

|

|

| Fig.1 | Fig.2 |

Questions about the multiple inscriptions that shape visual accounts of the Iraq War resonate through this sequence: who produced these images and on whose behest? Does the camera capture history in the making or does it record events that fit a pre-existing historical narrative, or that are even staged with this in mind? What is in the frame and what is beyond?

The footage, which forms a major part of Control Room and has been embedded into a new enunciative framework, cannot be exempted from such questions about context. As Michael Zryd notes about the re-appropriation of images:

History is not contained within the image. The capacity of the image to function as historical proof resides in its contextual frame, in what we have been told about the image (or what we recognise within it) who made it and why? Where and when was it made? [10]

The Footage – Provenance

The institutional provenance of news footage in Control Room is, with rare exceptions, identified by its signature logo. In almost all cases it is the AlJazeera archive as a repository for news that has been either produced by the channel, or for which it provided a platform of transmission. In a discussion of constituent parts of archival film, Paul Arthur traces a line of argument that conceptualises actuality as the modern version of Hayden White’s “unnarrrated events”, and thus as “devoid of enunciative or rhetorical specificity” and merely “denotative” or “evidentiary”. As Arthur notes, it seems difficult to countenance that “any product of mass culture can be successfully stripped of its contextual signification”. [11] The markers of institutional provenance in Control Room certainly undercut such an assumption as they activate framings to which AlJazeera has traditionally been subject.

By the outbreak of the Iraq War, AlJazeera had established itself as the Arabic-speaking station of choice in the Middle East and for the worldwide diasporic community of Arabs. AlJazeera was founded in 1996 following an invitation from the Emir of Qatar to journalists of the disbanded BBC’s Arabic language TV channel to set up a satellite channel. Dependent on state funding, AlJazeera replicates the prevailing financial model for TV channels in the region, but diverges notably from the editorial policies of a still largely state-controlled mediascape. The open political debate which AlJazeera fosters through formerly unknown formats, such as its flagship talk show The Other Direction, and the provision of a counter-narrative from an indigenous perspective, quickly made AlJazeera a global media force to be reckoned with. Such fame, reach and independence also brought temporary and permanent bans in a number of Arabic states. In the West, and by contrast, AlJazeera soon came to be cast as the “mouthpiece of Osama bin Laden”, a label first acquired when the channel became the recipient of the first instalment of the bin Laden tapes which it duly broadcast. Catherine Cassara comments on the ways in which AlJazeera has been framed across cultural faultlines: “Given its record as gadfly to the conservative, autocratic regimes of the Middle East, it is ironic that AlJazeera came to the attention of broader Western audiences as the representative of the most extreme form of Islamic reaction”.[12]

In Control Room such contradictory perceptions are recorded when Donald Rumsfeld accuses AlJazeera of trading propaganda and lies, while Saddam Hussein’s Information Minister issues threats against the channel for waging “American propaganda”. The overall picture of AlJazeera that ensues from Control Room, imputes its own connotations to the channel’s signature logo and ultimately the footage itself. The characterisation of AlJazeera in Control Room frequently draws on a juxtaposition of its journalistic practices with Western media. This forms the explicit focus of discussion with MSNBC’s Donald Shuster. In his view, AlJazeera successfully fulfils its journalistic remit by “ruffling a few feathers”. However, these efforts are constrained by the lack of a tradition of freedom of the press in the region. Noujaim’s editing delivers an implicit indictment of Shuster’s assessment. In the scene that follows, information on the fifty most wanted men in Iraq is offered to the assembled journalists, only to be immediately embargoed. The judgment of one of the disenfranchised correspondents, that this is “unbelievably inept”, summarises the inferences which this scene supports.

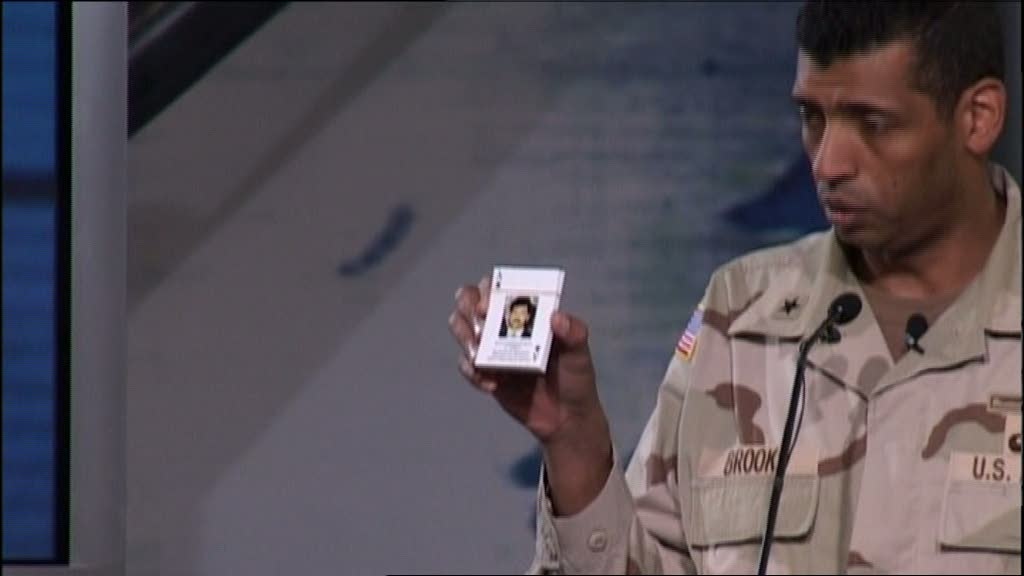

Representatives of the Western media are shown to collude with such instances of implicit censorship. When the “pack of cards” of Iraq’s fifty most wanted men is presented to journalists during a press conference, Noujaim shows a BBC journalist who engages in an act of witty camaraderie as he inquires if this will include the Iraqi information minister Muhammad Saeed al-Sharif, also known as Comical Ali in recognition of his fanciful information policy, since “every pack needs a joker”. It finally falls to AlJazeera’s correspondent to request that the proffered information be made available. A similar, all too easy consensus between the Western press and the military ensues as army officials “bury the lead” of the advance into Baghdad with the now discredited story of the rescue of Jessica Lynch, the GI who had purportedly been captured while fighting-off an Iraqi attack, and who was later rescued from an Iraqi hospital during a night raid by US marines. Lynch herself was subsequently to refute the official version of events as propaganda, stating that she had not fired a single shot, that there was no Iraqi soldiers in Nasirije hospital when it was stormed, and that she had been treated well and kindly by Iraqi hospital staff. Listening to the story of Jessica Lynch’s gallant rescue, one of the journalists thanks the speaker for “giving us this level of detail about Jessica Lynch” before she takes the bait by asking for more of the same. A little earlier AlJazeera journalists are shown as they greet the announcement of additional news on this episode with incredulity and disinterest. They instead seek information about the central news item of the day, the army’s advance into Baghdad. Noujaim’s portrayal of the Western Media and AlJazeera avoids simplistic oppositions. Thus, in one to one discussion, or in his statements to the camera, CNN’s John Mintier shows himself to be a vocal critic of the army’s media management. However, his shows of frustration cannot dispel doubts about the disempowerment of the media and the superiority of Western media practices which Shuster so readily claims.

This alleged superiority is also undermined by the instances in which AlJazeera correspondents emerge as a far more astute and reflective practitioners of their craft than their Western colleagues. It is Hassan Ibrahim who has to remind Josh Rushing that the context of war reporting has changed since Vietnam, and that his comparison of the bombing of Baghdad with the carpet bombing of Dresden is oblivious to the significance of TV in shaping public opinion. AlJazeera’s Joanne Tucker refutes allegations of bias by a British journalist who asks her: “Your journalists have a position on the war. Are they capable of being objective?” Tucker’s response questions this naïve application of the concept of objectivity. Her answer is contextualised by the due diligence she demonstrates by asking, “Are we sure about this news?”, as images of American prisoners of war are about to be broadcast. A subsequent scene shows Samir Khader as he rebukes one of his editors for a lack of balance in his choice of interviewee. If objectivity is, as Tucker states, an elusive goal, this scene suggests Al-Jazeera’s efforts to aspire to the best possible approximation of it; it attests to Noujaim’s portrayal of AlJazeera as a thoroughly reliable and competent source of information and reporting.

The Evidentiary Force of Footage.

In his provocatively titled essay “The Gulf War Did Not Take Place” Jean Baudrillard discusses the Gulf War of 1990 as a striking symptom of the “society of the spectacle”. The conflict serves him as prototype of war as “simulacrum”, a pure media event in which “events lose their identity and signifiers fade into each

other”. [13] This is not representation with a degree of transparency to the events themselves, but versions of these events that have become “coated” with speculation, uncertainty and self-reflection which renders them “sticky and unintelligible”.[14] Control Room is set in a realm of information processing and management that resonates with this description. It is a world which is saturated with TV images. Many of the events we see, such as the press briefings and interviews with government officials such as Bush and Rumsfeld, are staged for, rather than merely captured by, the cameras. The reality of an unfolding war seems far removed from this media hub. This is made explicit when a shot of a CentCom signpost that shows distances to a number of world locations is followed by an inter-title that lists the distance to Baghdad as 700 kms.

Noujaim juxtaposes this discursive world with the records of destruction, violence and suffering in the war footage. The air of urgency as casualties are raced to hospitals and the sense of chaos as a tangle of mutilated bodies is shown strewn across the floor, imputes these images with connotations of immediacy and authenticity. Angry outbursts by Iraqi casualties in which they blame Bush personally for the devastation they bear witness to, shatter the abstractions of war. The disparity between the world of CentCom and of actual warfare is brought home after journalists are denied access to the “pack of cards” (Fig.3).

|

| Fig.3 |

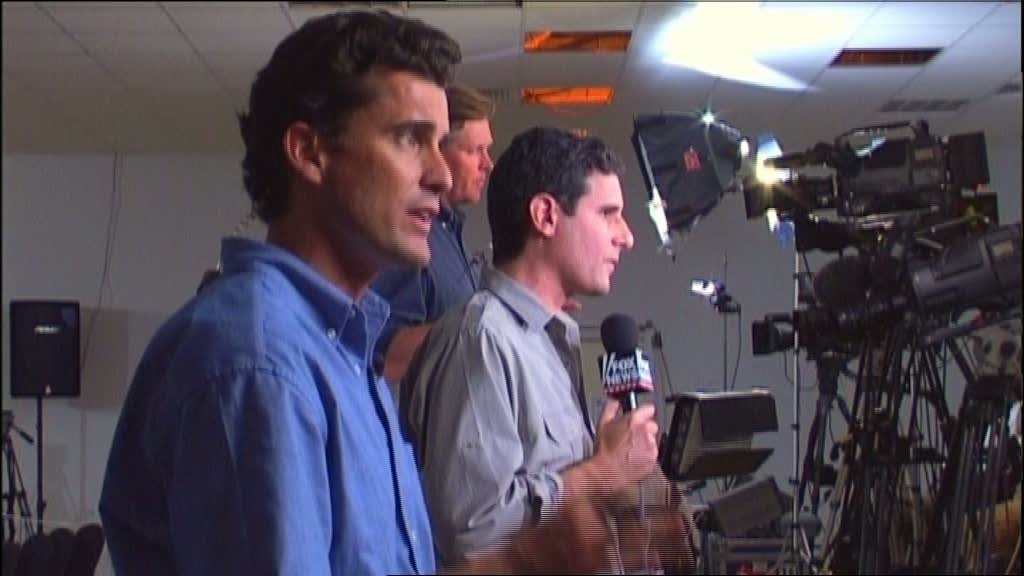

Left with nothing to report, a line-up of journalists is shown as they report on what they do not know about (Fig.4)—or in the case of AlJazeera’s correspondent, to sit and ponder (Fig.5).

|

|

| Fig.4 | Fig.5 |

The following shots of desert warfare and wounded civilians provide a potent reminder of the reality beyond their grasp. It also asserts the evidentiary authority with which Noujaim invests these images of war: by contrast to a realm of discursivity, they stake the forceful evidentiary claim of eye-witness accounts.

The integration of extra-textual footage in Control Room frequently draws on its summation by the film’s central characters. An early sequence establishes this close fit between the footage and its linguistic appendage. In this, Samir Khader claims that the US media has been “highjacked” to instill fear in the American people for which Saddam Hussein became a convenient target. Khader’s playacting of a popular American demand to “nuke him” brings about an abrupt transition to footage of detonating bombs. Later on, Ibrahim Hassan’s summary of American Foreign Policy as a case of “Democratise or I’ll shoot you!” calls up images of American troops in combat and of civilian casualties. In addition to this figurative verification of a verbal statement, Control Room features a number of instances in which the fit between image and word is entirely literal. This is particularly striking in the depiction of the events which surround the death of the AlJazeera correspondent Tarek Ayoub during the battle for Baghdad. In his account of this, Samir Khader explains that shortly before Ayoub was killed by American bombs, he asked for the camera to be moved away from his face as he sits anxiously on the rooftop of the AlJazeera headquarters. The soundtrack of the footage verifies his statement and the framing changes as requested. Throughout the film a process of mutual validation between linguistic framing and footage is at play. This validation is frequently supported by the impact of highly charged images of casualties of war that are prevalent in Noujaim’s selection of footage.

This epistemic force of the war footage is activated in a sequence in which Noujaim intercuts this with a press interview in which Donald Rumsfeld accuses AlJazeera of faking visual evidence to pretend that American bombs have hit women and children. Noujaim illustrates Rumsfeld’s statement with the very images he seeks to discredit. Wounded children are shown on hospital beds, crying women look upon a scene of destruction, and children wander through the rubble. At the end of the sequence an off-screen journalist’s question, “What about the footage of the children?”, is ignored by Rumsfeld, but again summons footage as proof of a reality that has been denied: the image of a disfigured and bandaged face of a child. In this constellation of two strands of footage Noujaim delivers a striking rebuttal of Rumsfeld’s accusation and reverse his charges against himself in a manner which Michael Zryd’s describes as “ironic re-contextualisation” in the re-appropriation of footage. This

ignites the subversive potential, which is inherent in many archival images as source of an official discourse, whether this emanates from government circles, industry or the media as purveyor of entertainment or news. Here too the material serves a proof, but not as proof of an event, but as proof of the insanity of an official discourse from which the archival material emanates.[15]

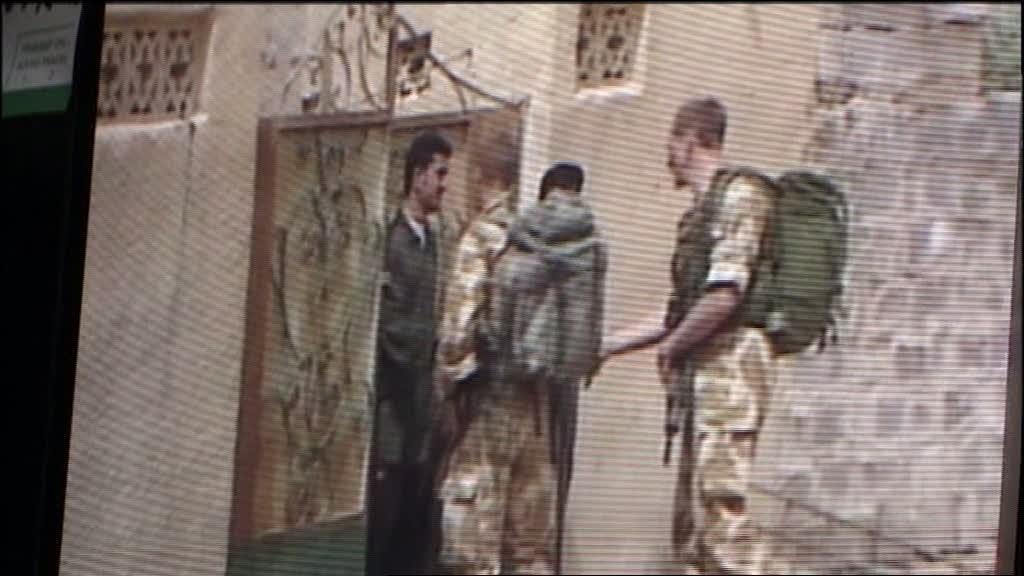

In the above sequence, footage provides evidence of a reality that is denied. This contrasts with a scene in which the evidentiary status of footage is explicitly questioned. It is one of three instances in which Hassan Ibrahim surveys news broadcasts of the war. One such shot sequence, one of the few in the film that do not carry a signature logo, features GIs as they are welcomed by Iraqi civilians. Ibrahim’s ironic comment, “Let’s see these liberating nice guys” inscribes these pictures with incongruity and unsettles any assumption that this footage might hold incontrovertible proof (Fig.6).

|

| Fig.6 |

However, such unproblematic evidentiary proof is once again assigned to the next shot in the sequence. The sight of a bomb crater where there was once a house is accompanied by Ibrahim’s assertion: “This is how Mr Bush is preaching democracy”. The implication of this statement is presently verified by a victim of this bombing who addresses the viewer with the statement: “I don’t want this democracy!”

Footage is not only recruited as evidence for truths and lies but also bias. An extended sequence of the film is dedicated to a discussion between media analyst Abdallah Schleiffer and Josh Rushing about the partiality of AlJazeera’s reporting. Rushing illustrates this with the example of a “promo-montage” which AlJazeera shows when cutting away to commercials. As he lists each component off-screen, successive shots of bombs, explosions and American tanks, culminate in the shot of a crying, bandaged child (Fig.7).

|

| Fig.7 |

However, the stylistic context of a montage sequence is dissolved as Noujaim cuts back to a shot of Rushing before the final image of the child appears. Severed from the stylistic context which underlies Rushing’s charge of bias and propaganda, the footage replicates the well-known iconography of images of warfare, but fails to illustrate his argument. Questioning any claims to an unproblematic referentiality in the reporting of the war, Noujiam nevertheless employs this assumption in her own use of footage. What Arthur refers to as “the spectre of evidentiary blockage and partiality”, is raised in a highly selective manner.[16]

Continuity from Fragments

Footage in Control Room comes in two different modi: it is a perennial part of the film’s diegesis as images flicker across screens and provide a focus of attention. Frequently this ubiquity assists seamless spatio-temporal transition. The first example of this features Bush as he announces the forty-eight hour deadline in the run-up to hostilities. Bush’s image must initially be inferred from the off-screen sound of his voice as staff in the AlJazeera newsroom watch in silence. From this, Noujaim cuts to a full-screen image of Bush which then transforms back into the size of a TV screen in a Doha coffee shop where he now is the object of attention for a new set of viewers. Smoothing over spatio-temporal gaps, footage assists transition and makes the film’s projected world cohere.

Other footage in Control Room has been selected and inserted and, as such, imports the potential disjunctures of a material mix into the film. In the words of Paul Arthur such re-appropriation results in “filmic structures in which recycled footage appears inevitably to privilege the perception of conscious construction over ‘unmediated’ presentation”.[17] In Control Room the visibility of conscious construction is attenuated through the way in which not only diegetic but also extra-textual footage is integrated.

Most notably there are a number of instances where the boundaries between the two types of footage become blurred. A scene might for example start with footage that originates from within the diegesis, but after a cut the imagery will fill the screen and lead into a series of shots whose anchorage within the projected world is uncertain. A particularly striking example of this comes in the three scenes which appear to flaunt the film’s recourse to archival footage. Each of these shows Hassan Ibrahim as he sorts through videos of recent news broadcasts. As these play on the screen in front of him he adds his commentary. If the use of pre-existing footage changes the filmmaker’s creative task to selection and arrangement, this sequence hands this task over to one of the film’s central characters. The first image displayed is of a dead child and elicits Ibrahim’s comment: “This child was essentially another weapon of mass destruction”. A shot of a detonating bomb comes with his laconic question, “Democracy?”. The sequence then continues with silent footage of coalition force soldiers who accost Iraqi citizens with physical and verbal force. The frame of a TV set which initially denotes these shots as one of the items in Hassan’s selection, then disappears. As the sequence continues with images of coalition soldiers who ambush a house, its inhabitants look on in a state of panic and confusion. However, any inferences about the status of this footage, whether the inclusion of this footage results from Hassan’s selection or whether it is inserted as authorial comment, remains uncertain.

An uncertainty of just whose perspective the footage conveys pervades Control Room: the film’s most overt visual commentary on the military intervention in Iraq comes in a montage sequence which consists of images of coalition soldiers as they force Iraqi men onto their knees. The sequence is intercut with a shot of women and children who appear to watch the scene (Figs. 8-9).

|

|

| Fig.8 | Fig.9 |

This assembly of images of humiliation is accompanied by the off-screen words of AlJazeera translator Muafak Tawfik: “All these pictures, who is going to miss all of this? Even a simple Bedouin can run it in the desert on a generator. They can see for themselves then”. However, when after the cut Tawfik is eventually shown as he sits in his office, an entirely unrelated image fills the screen behind him: there is no indication of whether he has commented on the picture which we have just seen or whether the use of footage in this instance is figurative rather than literal. The entire sequence is set to non-diegetic music and this contributes to an ambiguity about whether this is extant footage as it has been seen and commented on by Tawfik, or whether these images have been invested with their rhetorical thrust by Noujaim’s editing and arrangement.

Conclusion

At the close of Control Room Samir Khader offers his own conclusions on the fate that will befall the different accounts of this war. Reminding us of society’s short memory for the complex backgrounds of conflict, he concedes defeat on the battlefield of truths as he states: “There is one single thing that will be left: Victory. That’s it. People like victory. They don’t like justifications. You don’t have to justify. Once you are victorious that’s it!” If Control Room has presented us with two versions of this war, one of these will be submerged as history is being written. This concluding statement of the film guides our retrospective comprehension of the film and points to the significance of Control Room as intervention in the public discourse about the Iraq war.

In a global media environment, AlJazeera has been conceptualised as salient proof and example of an emerging contra-flow in global news reporting.[18] Hartmut Wessler’s investigation of whether this documents an interaction between traditionally dominant news flows and AlJazeera, or a mere reversal, comes to a sobering conclusion.[19] His analysis of the use of AlJazeera footage in the news programmes of three Western TV channels,F including CNN International (Eurofe), BBC World and the German Deutsche Welle TV, shows that it serves predominantly as decontextualised illustration for a narrow set of specific issues, or “Terror-TV-Fragments”.[20] As Catherine Cassara summarises it: “Western news outlets use AlJazeera as a convenient source of information in the Middle East, but rarely convey its takes on any of the stories they use”.[21] There is therefore little evidence for the emergence of “any form of enlightened discourse or a stable ‘communication bridge’” across the media divide. [22]

Noujaim’s selection of footage from the AlJazeera archives serves to validate the counter-narrative which the channel has come to symbolise. Her recourse to representational fragments of war defies an injunction which Baudrillard issues in the light of a sediment of “informational events” or an “informational aporia” left behind in the world’s archives. This representational surfeit of war defies conclusive critical analysis. Baudrillard predicts that “later there will be something to see for the viewers of archival cassettes and the generation of video zombies who will never cease reconstituting the event, never having had the intuition of the non-event of this war”.[23]

Control Room does not share this epistemological scepticism, and the changed discursive environment of a present day viewing of Control Room justifies this stance; following public disclosures about Abu Ghraib in April 2004, Bush’s calls to the Iraqis to reciprocate the humane treatment of prisoners now stands discredited. Donald Rumsfeld’s accusations against those who further their cause by lying, rebounds not least in the light of his denial of his involvement in the maltreatment of Iraqi detainees. Bush’s proclamation “that coalition forces have prevailed”, rings hollow. Accusations of propaganda, as AlJazeera claims that the war will be long and drawn-out, turn out to be a clear-sighted assessment.

Noujaim’s Control Room is an instance of representation in which, in Judith Butler’s words, “the mandatory framing becomes part of the story”.[24] The elusive nature of truth and the social processes which underlie its construction are a constant matter for discussion in Control Room. But what of the construction of Noujaim’s own framing of the frames, and therefore the way in which this thematic concern infiltrates the film’s formal construction?

With its strongly character-based approach, eschewal of overt commentary and thematic focus on what happens behind the scenes of institutions which construct news, Control Room displays an affinity that is acknowledged by its very title: the D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus documentary, The War Room (USA, 1993). It follows two campaign managers for the Clinton candidature in 1992 as they spin publicity in the run-up to the elections.[25] Acknowledging this stylistic lineage, John Hobermann asks whether Control Room can maintain an observational stance amongst the competing narratives it presents: “Can an independent fly on the wall elude the web?”.[26] Without seeking to rehearse well established arguments on the doubts whether any “fly on the wall” ever does, Noujaim’s use of footage with its conflation of authorial and character perspectives outlined above does most certainly not escape unharmed.

In his discussion of construction principles of films which are assembled from ready-mades, William Wees distinguishes between the formats of compilation, appropriation and collage. His categories reflect a scale of uses that ranges from the deployment of footage as unproblematic evidence to the investigation of the semiotics of representation itself. Drawing on Jay Leyda’s writing on compilation film, Wees offers a definition of the compilation film. This

may reinterpret images taken from film or television archives, but generally speaking, they do not challenge the representational nature of the images themselves. That is, they still operate on the assumption that there is a direct correspondence between the images and their pro-filmic source in the world. Moreover they do not treat the compilation process itself as problematic. Their montage may make spectators “more alert to the broader meaning of old materials”, but as a rule they do not make them more alert to montage as a method of composition and (more or less explicit) argument. [27]

Noujaim’s use of footage in Control Room asserts such an unproblematic correspondence between the image and the historical world it represents. Where the transparent window onto the world becomes blurred, it is shown as the result of wilful falsification with an agenda, rather than as the condition of all documentary imagery. In her essay ‘Mirror without Memories: Truth, History and the New Documentary’, Linda William describes truth as “the always receding goal of documentary”. The elusive nature of truth and the social processes which underlie its construction are a constant matter for discussion in Noujaim’s Control Room; however this thematic concern does not infiltrate the film’s own formal construction. Where Williams calls for “a careful construction, an intervention in the politics and semiotics of representation” in the engagement with the ever polysemous audiovisual record, the focus of Control Room is more accurately described as one of “simple unmasking or reflection”.[28]

If you are another who scream in open subject to getting hyper that if someone could write my term paper. Consider buying a term paper from us on reasonably cheap deal. Because we know that students have a tight budget and cheap custom term papers are what they deserve.

Works cited and consulted

Aday, Sean et al, “Embedding the Truth. A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Objectivity and Television Coverage of the Iraq War”, Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, vol. 10, no. 1, (2005), 3-21.

Allan, Stuart and Barbara Zelizer, eds., Reporting War: Journalism in Wartime.(London: Routledge, 2005).

Arthur, Paul, “On the Virtues and Limitations of Collage”, Documentary Box, vol. 11, (1997), 1–7.

Baudrillard, Jean, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press), 1995.

Bruzzi, Stella, New Documentary: A Critical Introduction, (London and New York: Routledge, 2006).

Butler, Judith, Frames of War. When is Life Grievable?, (London: Verso, 2010), 73.

Cassara, Catherine and Lengel, Laura, “Move Over CNN: Al Jazeera’s View of The World Takes on the West”, tbsjournal.com./Archives/Spring04/cassara_lengel.htm, 2004, (November 2010).

Chopra-Gant, Mike, Cinema and History. The Telling of Stories, (London: Wallflower Press, 2008).

Cortell, Andrew P. and Eisinger, Robert,M., “Why Embed? Explaining the Bush Administration’s Decision to Embed Reporters in the 2003 Invasion of Iraq”, American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 25, no. 5, (January 2009), 657 – 677.

Debord, Guy, Society of the Spectacle, (London: Rebel Press, 2004).

Hahn, Oliver, “Arabisches Satelliten-Nachrichtenfernsehen. Entwicklungsgeschichte, Strukturen und Folgen für die Konfliktberichterstattung aus dem Nahen und Mittleren Osten” Medien und Kommunikationswissenschaft, vol. 53, no. 2-3, (2005), 241 – 260.

Hoberman, John, “Seeing Double. A Room with a Different View: Digging through the Trenches of the Image War at Al Jazeera”, Village Voice, 11 May 2004. PAGES

Kolmer, Christian and Semetko, Holli A., “Framing the Iraq War. Perspectives from American, UK, Czech, German, South African and Al-Jazeera News”, American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 52, no. 5, (2009), 643-656.

Mor, Ben. D., “Public Diplomacy in Grand Strategy”, Policy Analysis, vol. 2, no. 2, (2006), 157–176.

Nichols, Bill, Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts of Documentary, (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press), 1991.

Plantinga, Carl, Rhetoric and Representation in Non-Fiction Film, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Reporters Without Borders, “The Iraq War: A Heavy Death Toll for the Media. 2003- 2010”, http://en.rsf.org/IMG/pdf/rapport_irak_2003-2010_gb.pdf , (November 2010), 2.

Thussu, D.K, “Mapping Global Media Flow and Contra-Flow”, in Media on the Move: Global Flow and Contra-flow, (New York: Routledge, 2007), 11-32.

Wees, William, Recycled Images. The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films, (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1993).

Wessler, Hartmut and Adolphsen, Manuel, “Contra-Flow from the Arabic World? How Arab Television Coverage of the 2003 War Was Used and Framed on Western International News Channels”, Media, Culture and Society, vol. 30, (2008), 439-456.

Williams, Linda, “Mirror Without Memories: Truth, History and The Thin Blue Line”, in Documenting the Documentary, eds. Barry Keith Grant and Jeannette Sloniowski, (Detroit. Michigan: Wayne State University Press: 1998), 379-396.

Winston, Brian, Claiming the Real: The Documentary Film Revisited, (London: British Film Institute, 1995).

Zryd. Michael, (2003), “Found Footage Film as Discursive Metahistory: Craig Baldwin’s Tribulation 99”, The Moving Image, vol. 3, no. 2, (2003), 40-61.

[1] Bruzzi, Stella, New Documentary: A Critical Introduction, (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), 17.

[2] Andrew P. Cortell and Robert M. Eisinger, “Why Embed? Explaining the Bush Administration’s Decision to Embed Reporters in the 2003 Invasion of Iraq”, American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 25, no. 5, (January 2009), pp.657 – 677.

[3] Reporters Without Borders, “The Iraq War: A Heavy Death Toll for the Media. 2003 – 2010”, http://en.rsf.org/IMG/pdf/rapport_irak_2003-2010_gb.pdf , (November 2010) , 2.

[4] For Josh Rushing such openness had its consequences. Following the film’s favourable reception at its Sundance premier in 2004, he was ordered by the Military not to talk to the press. He subsequently left the Marines, published the book AlJazeera Mission about his time as Press Officer during the Iraq War and now works for the English language version of the channel which was launched in 2006.

[5] Cf. Jehane Noujaim’s audio commentary about the film on the DVD released by Magnolia Pictures.

[6] Nichols, Bill, Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts of Documentary, (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991), 120.

[7] Aday, Sean et al, “Embedding the Truth. A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Objectivity and Television Coverage of the Iraq War”, Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, vol. 10, no. 1, (2005), 18.

[8] Butler, Judith, Frames of War. When is Life Grievable?, (London: Verso, 2010), 73.

[9] Allan, Stuart and Barbara Zelizer, eds., Reporting War: Journalism in Wartime, (London: Routledge, 2005), 5.

[10] Zryd. Michael, (2003), “Found Footage Film as Discursive Metahistory: Craig Baldwin’s Tribulation 99”, The Moving Image , vol. 3, no. 2, (2003), 121.

[11] Arthur, Paul, “On the Virtues and Limitations of Collage”, Documentary Box, vol. 11, (1997), 6.

[12] Cassara, Catherine and Lengel, Laura, “Move Over CNN: Al Jazeera’s View of the World Takes on the West”, tbsjournal.com./Archives/Spring04/cassara_lengel.htm, 2004, (July 2010), 3.

[13] Baudrillard, Jean, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995), 2.

[14] Baudrillard, (1995), 32.

[15] Zryd. Michael, (2003), 127.

[16] Arthur, Paul, (1997), 11.

[17] Arthur, Paul, (1997), 3.

[18] Cf. Thussu, D.K, “Mapping Global Media Flow and Contra-Flow”, in Media on the Move: Global Flow and Contra-flow, (New York: Routledge, 2007), 11-32.

[19] Cf. Wessler, Hartmut and Adolphsen, Manuel, “Contra-Flow from the Arabic World? How Arab Television Coverage of the 2003 War Was Used and Framed on Western International News Channels”, Media, Culture and Society, vol. 30, (2008), 439-456.

[20] Hahn, Oliver, “Arabisches Satelliten-Nachrichtenfernsehen. Entwicklungsgeschichte, Strukturen und Folgen für die Konfliktberichterstattung aus dem Nahen und Mittleren Osten” Medien und Kommunikationswissenschaft, vol. 53, no. 2-3, (2005), 254, quotation translated by the author.

[21] Cassara, (2010), 1.

[22] Wessler, Hartmut and Adolphsen, (2008), 457.

Hopes of bridging a cultural divide are raised in Control Room, if not at institutional, then at interpersonal level in the exchange between Josh Rushing and Hassan Ibrahim. Their initial difference of opinion on the political rationale for the invasion concludes with Rushing’s angry assertion: “I won’t back off of my opinion…” Towards the end of the film they discuss their diverging views on the fall of Baghdad. An act of liberation which is justified by instability in the region for Rushing, is a nation ransacked and the further promotion of US/Israeli dominance for Hassan Ibrahim. The agreement which they do reach is that “misunderstanding is running across the board”.

[23] Baudrillard, Jean, (1995), 47.

[24] Butler, Judith, (2010), 71.

[25] Jehane Noujaim’s previous film on the rise and fall of a dotcom business, startup.com, was co-directed with Chris Hegedus.

[26] Hoberman, John, “Seeing Double. A Room with a Different View: Digging through the Trenches of the Image War at Al Jazeera”, Village Voice, 11 May 2004, 1.

[27] Wees, William, Recycled Images. The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films, (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1993), 36.

[28] Williams, Linda, “Mirror Without Memories: Truth, History and The Thin Blue Line”, in Documenting the Documentary, eds. Barry Keith Grant and Jeannette Sloniowski, (Detroit. Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 1998), 393.