Introduction

When it is completed, Part Three will be the fifth instalment of a review of the lesser John Ford films contained in the gigantic Ford At Fox box set. It will cover most of the movies Ford directed at Twentieth-Century Fox from 1937 until he enlisted in the United States Navy after the bombing of Pearl Harbour. This segment, Part Three (a), consists of just one review. The coming segment(s?) will deal with films made later in this period. Part Two (a), (b) and (c) dealt with Ford-Fox films made from 1931 to 1936; and Part One with the silents contained in the box set.

Most attempts to periodise a director’s work are intended to provide readers with some guidance in its interpretation, and that is partly the case with my division of this review into numbered Parts. But the periods here are selected opportunistically rather than as the result of a grand interpretative design. They are dictated more by the contents of the Ford At Fox set than they are by the director’s overall career. This is perhaps most obvious in Part Two, where the first films are there simply because they are the earliest in the set which were made with soundtracks, but the “period” ends because certain thematic strands seem to have come together in a fairly complex and, I would say, satisfying way. A mere accident, a technicality, makes the last film mentioned in Part Two the last Ford made for “Fox Studios” (as distinct from Twentieth-Century Fox) and gives the period a veneer of proper historical periodicity.

Part Three works in almost the opposite manner. It ends just before an historic event of the sort that Changes Everything (the United States’ entry into the Second World World), but it begins with a film, Wee Willie Winkie (1937), which is there because of questions of craft and because of certain ideas the film seems to be articulating – that is, how it appears and how it thinks.

I am struck by how inconsistent Ford’s work is from 1931 to 1939 – and, as others have been, by how many of the more ambitious and better-known titles of that period were not made for Fox. But I am also struck by how the “upward trajectory” that Andrew Sarris once declared had commenced in Ford’s work with Judge Priest (1934)[1] begins to trend downward with Mary of Scotland in 1936 and takes until Stagecoach in 1939 to bounce back. (Some bounce!) By contrast, Tobacco Road (1941), a movie I am going to try very hard to appreciate, seems something of an aberration in the succession of features from 1939 to 1952, the date of the last of the Ford features in this box. And the foregoing suggests another way to periodise these films. Ford features from Mary of Scotland to Stagecoach: Mary of Scotland (RKO 1936), The Plough and the Stars (RKO 1936), Wee Willie Winkie (Fox 1937), The Hurricane (1937 Goldwyn UA), Four Men and a Prayer (Fox 1938), Submarine Patrol (Fox 1938), Stagecoach (Wanger UA 1939).

I am disappointed that the Ford At Fox set does not contain Submarine Patrol, which is a film that Tag Gallagher discusses side-by-side with Four Men and a Prayer (162-164).[2] And, of course, all of the journeyman productions, minor successes, turkeys and failures from 1936 through 1938 are quite a bit more interesting than one might think – at least they are if you are writing this review. But none of them is really in the same league as the Will Rogers trilogy and The Prisoner of Shark Island, which were featured in Part Two (c).

Ford features from Stagecoach (1939) to The Quiet Man (1952): Stagecoach (Wanger UA 1939), Young Mr. Lincoln (Fox 1939), Drums along the Mohawk (Fox 1939), The Grapes of Wrath (Fox 1940), The Long Voyage Home (Argosy Wanger UA 1940), Tobacco Road (Fox 1941), How Green Was My Valley (Fox 1941), They Were Expendable (MGM 1945), My Darling Clementine (Fox 1946), The Fugitive (Argosy RKO 1947), Fort Apache (Argosy RKO 1948), Three Godfathers (Argosy MGM 1948), She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (Argosy RKO 1949), When Willie Comes Marching Home (Fox 1950), Wagonmaster (Argosy RKO 1950), Rio Grande (Argosy Republic 1950), What Price Glory (Fox 1952), The Quiet Man (Argosy Republic 1952).

The features from 1939 to 1946 contain no less than four of the five Ford “classics” I mentioned in the first part of this review – the kinds of movies that I am only going to write about in a brief and disjointed way. Indeed, these films are the ones that absolutely established Ford’s status as a “master”. I would argue that of the remaining eight features in the box above only three are usually considered less than significant. And yet … and yet … I do think that his experience of the war changed everything for Ford, as it did millions of others, and Ido think that this change is significant enough to warrant labelling a separate period (1941-1952) and a separate Part (Part 4) in this review.

Darryl S. Zanuck, who took over at Fox in 1935 and who was most definitely a hands-on guy, would seem to be a leading candidate for the force most likely to be responsible for the consistency of the string of Ford at Fox movies made from 1939 to 1946. Ford, perhaps naturally, tended to resist this idea. He also tended to resist Zanuck, and after My Darling Clementine, made only “lesser” movies for Zanuck’s studio.

It is hard to know what to say about the Zanuck thesis. I suspect that the idea that the head of Fox had such an influence must have had at least a little to do with Fox’s willingness to make such a fine production of the Ford At Fox set, and so it has had a beneficial effect on you and me. There is a reasonableness about the story which Zanuck’s influence imagines – a story in which structure and social conscience are imprinted by Zanuck on Ford’s casual genius – one I suspect that Zanuck himself might have endorsed. (In this story Tobacco Road,When Willie Comes Marching Home and What Price Glory figure as instances of backsliding or deliberate insolence). But at the same time, there is a kind of opportunistic revisionism at work: only another strong personality equally dedicated to the art of the screen would have been able to tame this director’s wild spirit. In such an understanding film history continues to march along the well-worn path of Great Individuals; it is just that the path has been widened to accommodate two or three abreast.

I don’t mean to suggest that Zanuck did not have an influence, and a strong one, on these films – or even that his influence does not account for their current “classic” status. “Classic” is a word with infinite connotations of respectability, sobriety, craft and solidity. It is the state to which self-conscious bourgeois art aspires. The four “classic” Ford-Zanuck films are, it seems to me, monuments of bourgeois art in the same way that Four Sons is – monumentally worthy, resolutely good-intentioned and profoundly moving. Really, the sort of movie that you have to see only once, or never at all.

That good.

______________________________________________________________________________

Wee Willie Winkie (1937)

[See Addendum: Shutters]

The Steamboat Round The Bend DVD came from a DVD set of Will Rogers films that Twentieth-Century Fox issued in 2006. Similarly, the DVD of Wee Willie Winkie might seem to have originated in the six volume Shirley Temple – America’s Sweetheart collection issued by Fox from 2005 to 2008.[3] However, the Wee Willie Winkie DVD restoration was something of a joint Ford-Temple venture, with the new DVD version simultaneously appearing in both the most recent of the Temple collections and the Ford At Fox box. This is some restoration. Apparently 77 hours were spent on it, which is, I guess, a lot these days. Some blips remain on the dialogue track, corresponding to missing footage in the source material, but anyone ought to be impressed by the result. In this case the “Restoration Comparison” featurette is definitely worth looking at.

There is a different version of the film on each side of the disc. The one on Side B is black-and-white, but the A version is the same print retrospectively toned to approximate the appearance of the film’s first release. Mucking about with colour – or rather, the lack of it – in Shirley Temple’s movies has prompted some populist debate about the merit or otherwise of “colourising” those films. This toning, however, is not true colourisation – or, rather, the colourising performed here is a legitimate mimic of the toning that was actually applied to prints in 1937. Moreover, the tones used (mainly sepia, but with some night scenes in deep blue) suits the film perfectly, casting it into a past of faded photographs and utopic dreaming suitable for the time and place of its setting and for the hyperbolic nostalgia of its literary source, a short story by Rudyard Kipling.

Tag Gallagher says that Wee Willie Winkie, Four Men and A Prayer and Submarine Patrol are “naive little matinee pieces”, but almost in the next breath that Wee Willie Winkie is “next to Steamboat round the Bend the gem of the period” (160). He is right, of course.

This film is important in popular history for two reasons. It prompted a particularly lurid review in the British magazine Night and Day, written by Graham Greene, and which is sometimes cited as the principal cause of that publications demise soon after. It is also supposedly the source of one of the most enduring stories about John Ford, that lovable maverick character. Gallagher retells the story as everyone else does: “Ford ordered the studio cop to keep Zanuck off the set. When, later, Zanuck complained Ford was behind schedule, he tore out a bunch of pages from the script: “Now we’re all caught up.” And he never did shoot those pages” (133). I believe that I have read this anecdote attributed to at least three other directors, and I suspect that the incident may have happened over and over again. Perhaps it is happening again now.

The story told by the film

A pointed plot summary should prove useful. Young Priscilla Williams (Shirley Temple) and her mother, Joyce (June Lang), emigrate from the United States to “Northern India 1897” some time after the death of Priscilla’s father. There they are to become part of the household of Colonel Williams (C. Aubrey Smith), Priscilla’s grandfather, who commands the Seventh Highlanders on the dangerous frontier between what was then India and Afghanistan. They are met at the Raj Pore railway station by Sergeant Donald MacDuff (Victor McLaglen). In the town of Raj Pore itself, Priscilla picks up a talisman dropped by a Pashtun (“Patan” in the film) leader, Khoda Khan (Cesar Romero), who has just been arrested for arms smuggling, and attempts to return it to him, but is stopped by the authorities. One of the first people they meet is red-haired Lieutenant Brandes (Michael Whalen), who is young, attractive, something of a maverick, and whom Priscilla nicknames “Coppy”. The Colonel is not really looking forward to having two women living in his (rather spacious and well-appointed) quarters; and his attitude towards them, as well as towards Coppy’s more relaxed ideas of discipline, is antediluvian even by the standards of 1936. As part of a program to soften that attitude Priscilla decides that she will become a soldier. Coppy orders MacDuff to instruct her. MacDuff suggests that she can avoid the absurdity of being called “Private Priscilla” by adopting the name of “Wee Willie Winkie” – from a nursery rhyme she has apparently never heard of and he cannot manage to recall very well himself. “Private Winkie” does simple drill exercises, is given a uniform, and acquits herself well enough to win some affection from the men, especially MacDuff. Meanwhile Joyce is facing a rather more difficult initiation, especially after it becomes clear that Coppy fancies her more than he does Elsie Allardyce (Lauri Beatty), a proper daughter of the regiment.

Coppy takes Joyce to a sign that marks the very edge of the frontier (“and beyond that sign lies all Asia”) and tells her of the wonders on the other side, evidence of a great civilisation. Later he tells her that the promise of a peaceful accommodation between the British and Asia is what had drawn him to this post in the first place, but that now he believes he must leave because it is clear that the regiment/British policy is committed to conflict rather than negotiation and peace.

Because Priscilla has not been raised inside the closed world of the regiment (and perhaps because she is “naturally” born to oppose tradition), she questions the way things are done and insists on fair play rather than kowtowing to rank or regimental precedent. When she is discovered drilling with the men, the Colonel forbids all further military training and contact with MacDuff. This does not deter her ’satiable curtiosity. She has run-ins with the Colonel, Mrs Allardyce, (Constance Collier) and a drummer boy named Mott (Douglas Scott); she is also drawn to Khoda Khan, now imprisoned at the fort. Innocently she takes a message to him from Mohammet Dihn (Willie Fung) that informs him of a coming attempt to free him.

The result is an unexpected attack on the fort/compound, timed to take place during the regiment’s annual dance. Coppy has taken time out from his proper duties to meet clandestinely with Joyce when the attack starts. A feint towards the arsenal distracts the defence as Khoda Khan is taken from gaol. The Colonel is furious, and Coppy is placed under arrest. Joyce upbraids the Colonel and says she and Priscilla are leaving. The Colonel lectures them about the danger and his duty.

The cantonment is cut off and prepares for a siege. A patrol is sent out to the hills, commanded by Coppy, who has been released inadvertently when the Colonel remanded all sentences in order to have every man available to withstand the coming attack. The patrol is ambushed and Sergeant MacDuff is gravely wounded,

Joyce, Priscilla and Coppy are all struck with guilt. Priscilla visits MacDuff, who dies peacefully while she, all unknowing, is singing “Auld Lang Syne” to him. She determines to go to Khoda Khan and explain why the fighting must stop, and Mohammet Dihn – who by now is extremely unsettled and is anxious to get away from the fort himself – helps her achieve that aim. When her absence is recognised the next morning, the regiment sets out to bring her back, risking total annihilation because Khoda Khan’s forces completely control the key frontier pass where she has gone to find him.

In the denouement of this complex set of impulses and events the Colonel and Khoda Khan develop a mutual respect based upon their ideas of virtue, which Priscilla in every way exemplifies, and the stage seems to be set for the kind of peace and negotiation of which Coppy has been dreaming. In a military coda, Priscilla has been reinstated as Private Winkie, and praised for what she has done. She reviews the troops with her grandfather as Khoda Khan, Joyce, Coppy, and everybody else left alive looks on.

The story told by Kipling

It is routinely pointed out that the story told by the film of Wee Willie Winkie cannot possibly be the story Kipling wrote because Shirley Temple had to play the lead and Shirley Temple was a little girl whereas Kipling’s story was about a little boy. Sometimes it is noted that the boy’s name in Kipling’s story, Percival, was changed to a girl’s name, Priscilla, for the film. However my regular guide for this review, Tag Gallagher, definitely a fan of the film, says nothing at all about Kipling’s story, nor does he mention anyone else who has. And this is strange for the story told by the film is a much more nuanced one than Kipling’s, much more aware of the issues raised by colonialism and gender, much more interesting and well-crafted – just plain all around better, period. Moreover, the story in the film appears to me to be a deliberate repudiation of just about everything Kipling’s story endorses.

“Wee Willie Winkie” is the first story in Kipling’s collection, Wee Willie Winkie and Other Child Stories (1888). (The second story in that collection is the far better, and perhaps unintentionally harrowing, “Baa, Baa Black Sheep”.) There is a line within quotation marks directly under the title “Wee Willie Winkie”: “An officer and a gentleman” – and that is what the story is about. The first thing we learn about young Percival William Williams is that he “picked up the other name in a nursery-book, and that was the end of the christened titles”. The next thing we learn is that Colonel Williams of the 195th regiment was Wee Willie Winkie’s father, “and as soon as Wee Willie Winkie was old enough to understand was military discipline meant, Colonel Williams put him under it. There was no other way of managing the child … Generally he was bad, for India offers so many chances to little six-year-olds of going wrong”.

Wee Willie Winkie, whose self-selected name is always given in full in the story, is “managed” by awarding him with and depriving him of good conduct stripes (and pay). The common soldiers of the regiment come to idolise the boy “on his own merits entirely”. He is naturally good at nicknames, and styles Lieutenant Brandis “Coppy” because of the colour of his hair, thereby enhancing the officer’s standing with the regiment.

Yet Wee Willie Winkie was not lovely. His face was permanently freckled, as his legs were permanently scratched, and in spite of his mother’s almost tearful remonstrances he had insisted upon having his long yellow locks cut short in the military fashion.

Coppy becomes close friends with Wee Willie Winkie. Indeed we would say that he becomes something of a surrogate father or, perhaps as Kipling might have had it, an older brother. At any rate, the next thing that happens (within three weeks of Coppy’s naming) is that Wee Willie Winkie spots his friend kissing a “big girl”, Miss Allardyce. Quite a long exchange ensues as Coppy (successfully) endeavours to explain the nuances of pre-marital conduct to Wee Willie Winkie, who is hampered throughout by a simply atrocious “cute kid” accent in which “th” is mostly voiced as “v” and “r” mostly as “w” (e.g. “You didn’t tell when I twied to wide ve buffalo ven my pony was lame; and I fought you wouldn’t like”). Wee Willie Winkie agrees to keep Coppy and Miss Allardyce’s secret for thirty days, after which point their engagement will be announced.

Still, the boy cannot resist the temptations of India or, at least, the temptations of regimental life there. He accidentally burns up a week’s worth of horse fodder and is confined to “his quarters”. When he spots Miss Allardyce taking a ride “across the river”, where even Coppy never goes and where “it seemed to him that the bare black and purple hills … were inhabited by goblins”, he feels impelled to break his arrest. “It was a crime unspeakable”. He gets his pony and rides after Miss Allardyce, whose motive for crossing the river “was simple enough. Coppy, in a tone of too hastily assumed authority, had told her overnight that she must not ride out by the river”. Two wilful, naughty children then, in mortal danger. Now we know why Wee Willie Winkie thinks of her as “the big girl”.

Miss Allardyce’s horse stumbles and falls, and she twists her ankle. Wee Willie Winkie appears and Miss Allardyce tells him to ride back and get help from the regiment. Instead, after a bit, Wee Willie Winkie ties up the reins on his pony and gives it “a vicious cut of his whip” so that it heads back on its own.

“Oh, Winkie! What are you doing?”

“Hush!” said Wee Willie Winkie. “Vere’s a man coming – one of ve bad men. I must stay wiv you. My faver says a man must always look after a girl. Jack will go home, and ven vey’ll come and look for us. Vat’s why I let him go.”

At first Wee Willie Winkie is afraid that the men may be goblins, but when he hears “the bastard Pushto that he had picked up from one of his father’s grooms lately dismissed”, he knows that

People who spoke that tongue could not be bad men. They were only natives after all.

Then rose from the rock Wee Willie Winkie, child of the dominant race, aged six and three-quarters, and said, briefly and emphatically “Jao!”

“Who are you?” said one of the men.

“I am the Colonel Sahib’s son and my order is that you go at once. You black men are frightening the Miss Sahib. One of you must run into cantonments and take the news that Miss Sahib has hurt herself, and that the colonel’s son is here with her.”

(You will notice that, in an extreme instance of cuteness, Wee Willie Winkie’s problems with pronunciation do not carry over into Pushto.) Naturally the bad men are not about to take orders from a child.

“Are you going to carry us away?” said Wee Willie Winkie, very blanched and uncomfortable.

“Yes, my little Sahib Bahadur,” said the tallest of the men, “and eat you afterward.”

“That is child’s talk,” said Wee Willie Winkie. “Men do not eat men.”

A yell of laughter interrupted him, but he went on, firmly: “And if you do carry us away, I tell you that all my regiment will come up in a day and kill you all without leaving one. Who will take my message to the Colonel Sahib?”

…

Another man joined the conference, crying: “Oh, foolish men! What this babe says is true. He is the heart’s heart of those white troops. For the sake of peace let them go both, for if he be taken, the regiment will break loose and gut the valley.”

And much more to the same end. “It was Din Mahommed, the dismissed groom of the colonel, who made the diversion.”

The pony makes it back to the cantonment where it is spotted by Sergeant Devlin of E Company, who has not appeared in the story until now. Devlin rouses the troops, including a drummer boy named Mott, also introduced here, only a page or so from the end. Mott, who knows that Wee Willie Winkie cannot fall off his pony, also intuits that he must be across the river and in the hands of the Pashtans. A bloodless rescue is effected.

“You’re a hero, Winkie,” said Coppy – “a pukka hero!”

“I don’t know what vat means,” said Wee Willie Winkie, “but you musn’t call me Winkie any no more. I’m Percival Will’am Will’ams.”

And in this manner did Wee Willie Winkie enter into his manhood.

So there you have it. The whole of the rest of what I have to say about Wee Willie Winkie is only pointing out how the film text differs, mostly in good ways, from Kipling’s text. To that end, what follows will be more concerned with certain aspects of the film as a whole than it will be with Ford’s direction.[4] This does not mean that the direction is not worth discussing, only that I do not have the inclination to do so here.

Comparison, analysis, interpretation

The most important of the good ways the film differs from the short story are, I think, the changes mandated, or at least guided, by casting Shirley Temple in the lead. To move from “Percival” to “Priscilla” is to move from the realm of self-conscious legend to that of Victorian novelistic conventions. Priscilla is no knight of the round table; instead she is a fictional wonder girl.

But this fictional wonder girl is incarnated in the most popular child star of the thirties – herself a rather remarkable, and not wholly real, being. Surely the most immediately perceived quality of Shirley Temple onscreen is how utterly unlike any actual, living child she is. What we see is something almost wholly artificial, a animated doll, a sprite – all surface. In every one of her films that I have seen, Temple portrays a creature of inspiration and optimism, always apart, unmoved by the uneasiness and ambiguity of psychology, thought and responsibility.

These qualities combine with the gender change imposed by her casting in Wee Willie Winkie to force a change in the point-of-view from Kipling’s male-oriented story of military ideological indoctrination to one in which a specific historical situation is observed and (almost incessantly) interrogated. Temple’s Priscilla is once, twice, three times an outsider: first as a child, second as a female, and third as an artificial construct.

As if to underline this change, the film begins with Priscilla looking out at India from the window of a railway carriage. Reflections course across her face and her mother’s. Typically she is asking apparently naïve questions, but her mother’s answers are also naïve. Neither of these Americans can properly see what is unfolding before them in India. Her mother doesn’t even look.

There is just a suggestion of a shadow pattern within the carriage, visible above the characters. This visual motif will reappear throughout the film in heightened form as horizontal and vertical striations. The effect of the set design, lighting, and direction here is to ally Priscilla and Joyce in their separation, which quite quickly becomes a gendered separation as they attempt to find a way of living in the masculine-defined confines of the regiment.

Joyce plays a major role onscreen, whereas Wee Willie Winkie’s mother is entirely ineffectual in Kipling’s story, although she is mentioned twice. The differences between the two mothers points up the film’s somewhat enlightened treatment of women. When the Colonel refers to Joyce as a “helpless female”, she makes a point of reminding him, “I did my best to find work”, and Priscilla mentions more than once that Joyce put off asking for help from her late husband’s father until there was no other course. Both Priscilla and Joyce defy the Colonel, and Joyce comes as close as possible to leaving the cantonment with Priscilla because of what she perceives as the Colonel’s unfair treatment of her romance with Coppy.[5]

Sergeant MacDuff is next introduced to us and to Priscilla and her mother. At first blush, one wonders why McLaglen, a perfectly acceptable stage-Irishman, would have been forced to play a Scot, when his accent is so particularly execrable (after all, Kipling’s character is an Irishman named Devlin). But almost immediately there is the inevitable, conventional, (gender) joke about kilts and Priscilla’s inability to understand them even though she is herself wearing a dress. In this case, his kilt aligns MacDuff with the other women even before the character knows it himself.[6] In addition, I would say, McLaglen’s deplorable artificiality as a Scot plays very well off Temple’s own artificiality, moving the two effortlessly into that realm of conventional performance that served Ford so well in the Rogers films.

The Scots, common soldiers all, are distinguished throughout from the English officers of the regiment – and they are represented much more positively than are the regiment’s officers, Coppy excepted. That the distinction is based on ethnicity rather than class is surely intentional and surely some viewers at least would have recognised an implicit comparison/contrast with the rebellious Patans, introduced next in the character of Khoda Khan, who is not in Kipling’s story at all.

Khoda Khan is hard evidence that Cesar Romero was capable of acting. Romero is very effective as a “good bad man”. One never believes he is a conventional villain, but rather a noble character temporarily self-cast as a menace. This means that Priscilla’s trust always has a solid experiential base for the audience – and the expansion of the character as well as its role in the film’s narrative ensures that the film makes room for a critique of a certain kind of colonialism. Here, as before and to come, the character is introduced to us and Priscilla as something she perceives or discerns.

As it happens, the next significant character introduced in this manner is Khoda Khan’s secret ally, Mohammet Dihn, whom Priscilla tentatively identifies as her grandfather. Kipling’s Din Mahommed is instrumental in changing the minds of the bandits who have trapped Wee Willie Winkie; he helps to rescue him from captivity. Mohammet Dihn plays a more complicated, and far less positive, role in the film’s story. Indeed, so conflicted and noxious is his treatment by the film that the only way his character can be resolved is through madness and summary execution. At first it seems that Mohammet Dihn will be a comic character, not unlike those played by Stepin Fetchit. He is servile, difficult to understand, lazy and deliberately obtuse. However, when he enlists Priscilla to carry a message to the imprisoned Khoda Khan he takes on a more sinister cast. After his leader’s escape he makes preparations to flee the cantonment – preparations which are menacingly intercut with a significant dialogue between Priscilla and her grandfather. Priscilla leaves that dialogue resolved to go and find Khoda Khan, and Mohammet Dihn promises to take her to him – believing she will prove a welcome hostage. He giggles more and more during the journey, and even more when he finds out that his actions do not meet with Khoda Khan’s approval. When news of the regiment’s arrival is brought, Khoda Khan orders him tipped over the side of his mountain top fastness.

The Mohammet Dihn character in the film, unlike Din Mahommed in Kipling’s story, is clearly an ugly ethnic stereotype. But we mustn’t be too quick in identifying the ethnicity of that stereotype as Muslim. The noble Khoda Khan, even if he is played by Cesar Romero, is much more clearly a believing Muslim than Mohammet Dihn; and this is because Mohammet Dihn is not only played by an ethnic Chinese actor, Willie Fung, but is played as an ethnic Chinese stereotype – which only adds to the unnecessary offensiveness of the characterisation.

In Kipling’s story Coppy had two functions, one dependant upon the other. The main function was to act as an elder brother/surrogate father to Wee Willie Winkie, and the dependent function was to introduce the child to adult romance and its consequences (including chivalry). In the film Coppy is a bridge between Priscilla and MacDuff, and also between Joyce and life in the regiment – that is, in both cases he mediates ultimately between the women and the Colonel – but in no way does he seem to mediate between Priscilla and adult romance. Crucially, he represents a more enlightened attitude towards “Asia” than anyone else associated with the regiment – but he is also marked clearly as the Colonel’s successor, that is, as one who will simultaneously continue the (colonialist) tradition of the regiment and somehow ameliorate that tradition.

The Colonel, introduced finally after all the other narratively significant characters, is not the protagonist’s father, as is the case in the Kipling story, but her grandfather – the object of her initial quest and the several mis-identifications that quest has engendered. The disparity in age as well as in culture (British/American) explains rather well the distance between them and the Colonel’s inability to control the child, a question that is not even raised in Kipling’s story. However, what seems to be stressed in Ford’s film is a conflict of conventions: Shirley Temple’s irresistible force against C. Aubrey Smith’s immovable object, her questioning against his certainty, her new beginning against his desiccated tradition.

Between the railway carriage and the Colonel are the broad social and cultural issues that the film is thinking about, just as between the introduction of the Colonel and Priscilla’s first visit to Khoda Khan are stretched the specific issues the film is thinking about.

We experience India initially as a set of words (“Northern India 1897”) and a flourish of music that promises excitement. A train spouting black smoke cuts through a pass and steams towards us. In a Hitchcock film, say The Shadow of a Doubt, such a train would presage disaster. Here it seems to signal only adventure.

Priscilla sees India as landscape which we can perceive through the railway window behind her when she turns to question her mother. The congruence of her and our point of view at the same moment that the separation of our and her understanding is being stressed in the exchange of dialogue sets up a disjunct, if commonplace, relation between audience and protagonist, sound and vision, which the film will finally resolve in a series of improbabilities. From this point we are bound to her, each of us watching, inexperienced, displaced (déplacé), within our respective situations.

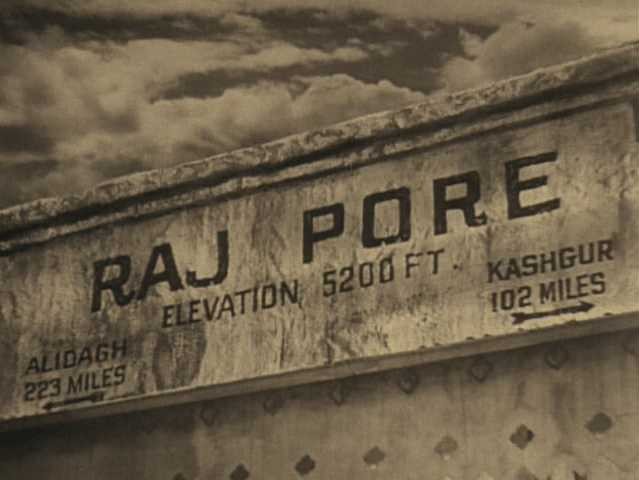

Yet despite this relation, we rush ahead of Priscilla to a sign.

More words. “Raj Pore”. A destination in India. Is this where we are going? “Elevation 5200 ft”. Does this mean it is high up? Why does the sign say anything about elevation? “Alidagh 223 miles”, “Kashgur 102 miles”. Names we – western observers like Priscilla – may hardly be able to read, much less to pronounce, much less to locate in our minds. Where in India are they? What do they mean? We are asking questions like Priscilla, without even knowing it.

India, then, is explicitly an object of curiosity, a place that needs explaining – and that, as we shall see shortly, only partly explains itself.

Three shots of colonial spectacle establish Raj Pore and the train coming into the station. The last two of these are of the train. Bearded men in turbans lean out of the railway windows smiling, perhaps coming home – a typical Orientalist vision predicated on the difference of the Other, hiding our kinship with it.

But the next shot implicitly asserts that kinship, for it is the first strong reverse shot in the film, and it is of the interior of Priscilla’s carriage. Her point of view is the point of view of the bearded men, and she is as pleased by what she is seeing as they seem to have been. “Look Mommy, there’s an elephant! Are we going to ride the rest of the way on an elephant?” In spite of her kinship with those men, she does share the Orientalist desire to become one with the seduction of the exotic, with difference, with a new life – with an elephant[7] – which presumably they do not.

Priscilla is utterly delighted by the spectacle of Indian poverty when beggars rush the train – because, I suppose, we are to understand that she mistakes it for welcome – but the film continues its display of difference right through to MacDuff’s kilt, encompassing the Scottish military in its assertion of fascinating Otherness and coaxing us to make distinctions in degrees of difference that presumably Priscilla does not (honi soit qui mal y pense). MacDuff leads the two pilgrims on a clear path through a juggler, vendors waving plates of fruit, and holy beggars. The path leads to another vehicle, a sort of stagecoach, driven by one of those bearded men in turbans. Priscilla asks him if this is where the circuses come from, and he answers, “Yessss. Very hot day”, which disappoints but does not discourage her. After all, we may think, if you ask a stupid question you can expect a stupid answer. Later, when “Yesss” turns out to be what every Indian official and rebel spy says in reply to every English colonialist attempt at interpellation, we may think that it is not the stupid answer it first appears. Rather than signalling incomprehension it implies insubordination.

On that level, a level on which some may always already understand the bearded subaltern’s “Yessss”, we are witnessing the curtain rising on the a new act of the colonial spectacle, in which we, and to some measure Priscilla, are privy to an act of rebellion – a step up from insubordination. We see fully the mishap which reveals the rifles, the dramatic tracking shot that identifies Khoda Khan, and the honourable impetuosity that results in his arrest (following a sequence of police whistles as interpellative as any Althusserian could wish). We have been taken extremely swiftly from an exotic tourist spectacle of indigenous difference and colonial fascination to an equally exotic conflict between indigenous freedom fighters and colonial oppressors. Priscilla, the spectator, the questioner, the white American girl, knows instinctively who has been wronged and how (Khoda Khan has lost his amulet in the struggle with the local authorities). Perhaps we are not immediately so sure, although there are several hints in the way the direction, montage and script emphasise the anxiety evoked by the callous and unthinking response of the authorities, including MacDuff, instead of the stock Oriental villainy we might have expected.

The coach makes its way to the regiment’s headquarters, and another level of the narrative, through a landscape we already know is more an abstract site for adventure than a specific location in India. Here again in this John Ford film, as so often in Kipling’s fiction, convention confounds convention, only a movie, just an image.

”But Mommy, if we’re in India, where’re all the Indians?”

“They’re not the same kind of Indians that we have in America, darling.”

“What kind are they, then?”

“These are the real Indians. The ones back home were called that by mistake because … [a little exasperated] when Christopher Columbus discovered America, he thought it was India.”

“Then, is grandfather an Indian?”

“No dear, he is an Englishman, a colonel in the army. You know that.”

“Then why doesn’t he live in England?”

“Because Queen Victoria transferred him here.”

This exchange, which opens the film, also opens the tangle of colonial conventions that the film surveys. Priscilla surely has already seen many people from her railway carriage, but none of them look like Indians to her – because they do not look like the same kind of Indians “that we have in America”. But Priscilla is unlikely to have seen many, perhaps not any, native Americans, living on the East Coast as she did. The Indians she, and her mother, are most likely to have seen are iconic Indians, the ones imaged in western paintings and magazines – Frederick Remington’s Indians, Edward S. Curtis’ Indians – very like the ones that viewers might imagine, those who appear, somewhat later, in western movies, some directed by John Ford.

These, of course, are not “real Indians”. Her mother implicitly promises Priscilla that the Indians they have seen and will see (and that we are about to see) are “real” – but by that she appears to mean “first” or “original”. The firstness of these Indians, however, does not separate them altogether from their American counterparts, known sometimes as the “first” Americans. In invoking “American Indians” right at the beginning, certain parallels between the situations of Indians in America and Indians in India are also suggested by the film. These parallels are reinforced by Priscilla’s grandfather being “a colonel in the army” “transferred” by his government to India.

Colonel Williams is not an Indian. He is an English man in India. Priscilla and Joyce are not Indians either. They are American women in India. They are all three displaced, but Priscilla and Joyce are displaced in history as the colonel is not, by virtue of their geographical and gender identities.

Two iconic historical figures are also mentioned in this exchange: Christopher Columbus and Queen Victoria, on one level America and Britain. But the masculine one, Columbus, is the iconic discoverer, someone who opened worlds undreamed of, iconic also because of his misidentification of what he had found, because he mistook the new world for the old. Queen Victoria’s iconic status derives from her association with tradition, the ways things have always been. Queen Victoria signifies the persistence of the past into the present and future: the inability to see the new world revealed by the working of time. Feminine Victoria may be, but her closest association in Wee Willie Winkie is with Colonel Williams, the Ur-masculine representative of the Crown who in the end corrects its flawed vision, just as the ultra-”feminine” Priscilla and Joyce correct Columbus’ abstract misperception by recognising the possibility of a new world within the old.

Priscilla is not satisfied that Colonel Williams should be an Englishman and not an Indian. The exchange leaves her with a puzzled expression, and her puzzlement mounts, along with her delight, in the town of Raj Pore, a place that displays Indians and their doings as a colonialist spectacle.

that pleasant pageantry … is the arrogant, racist and resented position of the British. We see that position in almost every scene, whether with English ladies shopping, English gentry in a tea shop, English officials supervising native police, English breaking through train-station crowds, or English balls interrupted by attacking Pathans. Pax Britannica vs. native rule. Everywhere can be sensed the flag, the cross, and British music. “England’s duty, my duty,” huffs the colonel. (Gallagher 161)

It puzzles Priscilla that she is not understood by the coach driver, and even more that she is not allowed to return Khoda Khan’s talisman. But there is something even more puzzling in the events that happen in Raj Pore, something that is never directly acknowledged as a source of puzzlement for Priscilla: Sergeant MacDuff condemns Khoda Khan out of hand as a troublemaker and never afterwards indicates that he is aware of any conditions that might be onerous for Indian or Afghan people – although he is clearly aware of conditions in the army itself that he believes are unjust and onerous (and this is one reason he undertakes to mentor Priscilla).

Yet Khoda Khan’s arrest becomes the focal point of Priscilla’s puzzlement. She condenses the situation down to a simple question.

Priscilla: “Why is everybody mad at Khoda Khan?”

Private Mott: “Ha! That’s a good one, that is: ‘Why is everybody mad at Khoda Khan?’”

The “everybody” to whom Priscilla is referring certainly includes MacDuff, even if Khoda Khan is the subject of their conversation only once. And it certainly does not include Mohammet Dihn, who has already sent her to see the imprisoned Khoda Khan, or any other Indian or Patan character. Why everybody is mad at Khoda Khan is never really made clear to Priscilla, or to us. Mott, like almost everyone else – the Colonel most recently in the narration (see the scene described by Gallagher below) – takes the situation as given. Coppy is the only other person who even hints at that question, however indirectly, in his paean to what lies on the other side of the frontier.

Later, Priscilla repeats the question to the Colonel, which leads to a most interesting exchange, supplemented by an exercise in what would have been called at the time “parallel montage”.

Colonel: “We’re not mad at Khoda Khan. England wants to be friends with all her people. But if we don’t shoot Khoda Khan, Khoda Khan will shoot us.”

[Their conversation cuts to Mohammet Dihn preparing to flee and stealing things from the house.

The Colonel explains that the regiment’s job is to keep the pass open so that trade can cross the borders and benefit everyone, even Khoda Khan.

CU of Mohammet Dihn’s hand with a knife.

Cut to CU two-shot of Colonel and Priscilla:]

Priscilla: “Couldn’t you go and explain all that to him?”

Colonel: (Laughs ruefully) “It wouldn’t be much use…”

[Mohammet Dihn leaves while the Colonel’s voice over continues:]

“… For thousands of years, these Patans have lived by plundering…”

[CU two-shot of Colonel and Priscilla again] “… They don’t seem to realise that they would live much better if they planted crops, traded and became civilised.”

Priscilla: “But grandfather, I don’t want anybody more to get killed.”

Colonel: “Neither do I, my child, neither do I. [Kisses her] But don’t worry your little head about that any more tonight.”

A lot of the unsatisfactory nature of this explanation hinges on the dismissive quality of the Colonel’s last line, just as a lot of its “justification” (if one can call it that) hinges on the menacing quality of the intercut shots of pillage in a sequence of actions which might otherwise have been imaged as those of a very frightened person. It is, I should say, a happy accident of the medium that one can find other explanations for these shots, which after all are not signs of imminent physical danger for any of the white people in the cantonment.

The Colonel’s position is more certainly justified by the lines about how the rebels would be better off if they radically engineered their traditional way of life into a semblance of pre-industrial European culture (say around the eighteenth century). This is a general position that, at least later in his life, made Ford uneasy, and even made some nineteenth century British imperial types uneasy – types like Coppy, the Orientalist romantic. Today we are more likely to recognise such a policy as both tyrannical and impossible to implement.

It is interesting that Priscilla does not respond to the Colonel’s argument (and indeed will reiterate it shortly to Khoda Khan). She merely says that she does not want more killing. Intuitively she recognises that the Colonel’s arguments amount to an excuse for not taking steps to make the future he has claimed the Empire wants – a future in which there is no killing. Indeed, the Colonel here indirectly evokes the Queen (“England”) as a harbinger of change, not a bastion of tradition. He has begun to realise that he is trapped by the conflicting conventions of his role.

After Priscilla leaves the Colonel she determines to go to Khoda Khan, demonstrating that, unlike the Colonel, she will act to achieve peace. She accepts Mohammet Dihn’s offer to be her guide. On the journey she is again confronted by the colonial spectacle of exotic landscape, peoples and customs. Khoda Khan and his followers are ensconced in luxury at the topmost level of a tower beyond gauze curtains. Her arrival precipitates the same kind of reaction in Khoda Khan that his own arrest precipitated in the Colonel: recognition that having this prisoner is certain to provoke hostilities.

Here is part of the conversation between Priscilla and Khoda Khan:

Priscilla: “Then don’t you think it’s awful silly to be mad all the time and fighting when you don’t have to?”

Khoda Khan: “Why don’t you ask your grandfather that question?”

Priscilla: “I did, and he said he didn’t want the war but you wanted it.”

[Khoda Khan laughs and translates to the others who laugh too]

Priscilla [with her mouth full]: “Then you would stop the war, wouldn’t you, if I can make you understand?”

Khoda Khan: “What is there to understand?”

Priscilla: “But my grandfather told me that the Queen wants to protect all the people and make them happy and rich and all that!”

[Khoda Khan laughs, translates to the others, who all laugh loudly except one who looks thoughtful.]

…

Khoda Khan: “Between your people and my people there must always be war.”

[Priscilla says that this means that her grandfather was right and that Khoda Khan does want war.]

As far as she is concerned, the choice between war and peace is simple – and so, of course it is for both Khoda Khan and the Colonel. The Colonel claims that Khoda Khan is culturally impelled to war; and Khoda Khan claims that the British (always) lie, especially about their peaceful intentions – that is, that the British are culturally impelled to conquest/war – and that furthermore war between the British and the Patans is a condition of their existence.

It is significant that these two positions are presented as a conflict between cultures, a colonial conflict. We have been witness and party to various ways in which the English have asserted their dominance. We have been witness and party to ways in which Patans and Indians have resisted that dominance. And it seems to me that the Empire has not come off well in the comparison. Moreover, the conventions of (classical) narration alone will have already informed us that this irreconcilable conflict of cultures must be reconciled in the end of the story. To put the situation in slightly different terms, the film rejects cultural determinism in favour of finding a resolution on a higher level.

If the Colonel dismisses Priscilla by belittling her mind and invoking her status as a child, Khoda Khan dismisses her by laughing at what she says and translating her words to his mocking followers, another way of invoking her childishness. Indeed the laughter of these men reprises an earlier incident in which high ranking British officers laughed at the sight of her drilling with the men. Yet it is Khoda Khan who is brought directly to recognise the injustice of his attitude. He comforts her when she dissolves in tears because her efforts to make peace are only producing laughter and rebukes the others for continuing to laugh at her. His protective care is only interrupted by news of the arrival of the rescue expedition.

Thus the discussion with Khoda Khan remains unresolved just as the discussion with the Colonel was left unfinished, and the questions asked in those discussions are never directly answered by any of the participants. But then Priscilla impulsively repeats the action she had taken when she left the safety of the regiment to appeal to Khoda Khan. She runs out of the crowd around Khoda Khan and into the line of fire in order to help her grandfather.

Surely we are to understand that this action and its predecessor move the discussion about war and culture to an entirely different level, the level on which Priscilla happens to have been operating the whole time. She has acted, immediately and intuitively, on her conviction that the killing must stop, prompting first the Colonel and then Khoda Khan to act to prevent her being killed, and in the process to recognise that the two sides, Prospero and Caliban, do share some common ground in their regard for the person of Miranda, the wonder of the world, the child who acts for peace.[8]

Children, women, colonialism, vision

This 1937 film was preceded in Afghanistan by a period, 1926-1929, when Soraya Tarzi, then queen of that country, was instrumental in introducing radical reforms for women. In one speech she said:

It (Independence) belongs to all of us and that is why we celebrate it. Do you think, however, that our nation from the outset needs only men to serve it? Women should also take their part as women did in the early years of our nation and Islam. From their examples we must learn that we must all contribute toward the development of our nation and that this cannot be done without being equipped with knowledge. So we should all attempt to acquire as much knowledge as possible, in order that we may render our services to society in the manner of the women of early Islam.[9]

In the Preface to Wee Willie Winkie and Other Child Stories Rudyard Kipling also has something to say about women’s knowledge; but he relates that knowledge specifically to the privileged knowledge that only children possess.

Only women understand children thoroughly; but if a mere man keeps very quiet, and humbles himself properly, and refrains from talking down to his superiors, the children will sometimes be good to him and let him see what they think about the world.

Without in any way suggesting that Ford’s film displays any direct engagement with Sorya Tarzi’s words, Wee Willie Winkie does seem to display more of her global modernist idea of the role of women than of Kipling’s arch paternalism. As I have suggested, one of the clever things the film does is to treat Priscilla and her mother together for much of the time, thus emphasising their gender, and the relation of that gender to the positions they, together and separately, take on regimental life.

After the coach ride out of Raj Pore, the film turns its attention to the regiment and to the difficulties which must be overcome for mother and child to exist there. For Joyce these difficulties are manifested in the life of the small British community that has been extruded by the regiment, while Priscilla attempts to integrate herself within the walls, so to speak.

When the Colonel refers to her as a “helpless female”, Joyce contrives to mention that the reason it has taken her so long to appeal for his help after her husband’s death is that she was trying to find work, that is, to make her way without anyone’s help. The mother and child’s mere survival is testimony to her success as much as their presence in India is to her failure. Aside from the uncomfortable attitude of the Colonel himself, Joyce and Priscilla actually have a fairly easy time fitting in. Joyce’s potential rivalry with Elsie Allardyce is dissolved by Coppy’s immediate attraction to her and smoothed over by Mrs MacMonachie’s connivance and the acceptance that implies.

Priscilla works out on her own that she has to be a soldier if the Colonel is going to like her. “You see,” she explains to Coppy, “The Colonel’s never had any little girls around.” Coppy then orders MacDuff to instruct Priscilla how to be a soldier, in something of a running gag about the delegation of authority within the regiment. Priscilla imitates the movements of soldiers extremely well. And, although

MacDuff suggests the Wee Willie Winkie name, she, rather than MacDuff, realises that her military title will be Private Winkie.

Priscilla is not the only outsider attempting to find a reasonable place within the regiment. Mott (Douglas Scott) appears early in the piece as the butt of the soldiers. Priscilla asks Mott how to get to be a soldier, but he scorns her request; clearly he regards her as a nuisance because she is a girl. There is also a scene of interaction between the two that climaxes with Priscilla following Mott around and imitating his military stride. Gradually in other ways as well she takes his place. Mott’s uniform is shrunk to Priscilla’s size in boiling water as a sort regimental initiation “joke” by MacDuff and his friends. The next shot shows Priscilla wearing it. Mott is given two dogs, both of which he intends to keep for himself. He says he would trade one for something of Priscilla’s, but she has only “girl’s things”. MacDuff half tricks, half cons, Mott into giving one back, which MacDuff then passes on to Priscilla. There is no question but that in the minds of the soldiers, Priscilla is, for no accountable reason, a more satisfactory Mott.[10]

Gallagher says that “Priscilla … can mime the imperialist spirit Stepin-Fetchit-like” (161), which seems about right if it is agreed that Stepin Fetchit’s mime was a form of cultural resistance. But Gallagher seems to think that the film endorses British imperialism because Priscilla is adopted as the regiment’s “mascot”, when surely the point is that she is not anyone’s mascot. She twice refers to her training with MacDuff as “play”, which of course is precisely what Kipling’s Percival would not say about his comparable situation. Indeed, Private Winkie makes little sense considered as a mascot unless by “mascot” is meant the living spirit of the regiment. The conclusion that the film endorses British colonial imperialism mirrors what Andrew Sarris says of the film in The John Ford Movie Mystery: “…as the supposed Irish patriot of The Informer and The Plough and the Stars [Ford] was compelled to perpetuate Hollywood’s glorification of C. Aubrey Smith’s British Empire, shifting from Liam O’Flaherty to Rudyard Kipling.”[11] But surely Priscilla represents what hope of escape from their situation there may be for the others in the film, all embedded one way or another within a vision of colonial imperialism.

The narration of this part of the film is fashioned around a succession of small victories as Joyce and Priscilla begin to win the Colonel over to the idea of including women in his vision of the regiment. For example, it is the Colonel who settles what might have been a very disruptive dispute with Mrs Allardyce by laughing it to scorn. When Priscilla disobeys her grandfather to join a three-hour punishment drill that he has imposed on the group with which she has been training, she cannot make it back and must be carried by MacDuff. The result is that he forbids her trying to be a soldier at all. Such unbending lack of understanding is also nearly the cause of the pair’s permanent departure, when he abruptly dismisses Joyce’s plea for tolerance after Coppy has been imprisoned for having left his post to visit her during the regimental ball. This is what Gallagher has to say about that scene:

The scene in which the colonel attempts to justify duty’s point of view is set with stunning expressionism in a darkened room, he to the left engulfed in shadow, Priscilla and Joyce in the middle, their white dresses illuminated. The composition lends majesty to his words, but lends them subjectivity, too. He does not quite win his point. (162)

This “composition”, if that is what it is, also lends a great deal of integrity to what the American women say and a great deal of menace to what the Colonel says. Set beside the women, the Colonel cannot help but abuse his power, as he has been doing from the beginning of the film. In the later scene between Priscilla and the Colonel which has already been discussed, the two actors are shot at the same level, and it is clear that Priscilla’s white nightdress marks her as the one who is in the moral ascendant.

Kawaii and bushido, the inhuman child and the outcast warrior

Shirley Temple is well-cast because the isolation that surrounds Priscilla (her foreign-ness, her inexperience, her not having a place – but also that peculiar impersonal aura of Temple’s) is what allows her to do what no one else can or could. Gallagher points out that Priscilla is “Ford’s most affirmative hero … her higher wisdom derives … from an innocence reflecting humanity’s innate virtue” (160). That innocence is, from another point of view, one of the qualities of her inhumanity. Priscilla is inhuman as a saint is inhuman, a monster of virtue like Simone Weill.

In my viewing of the film for this review I have been struck by the quality of kawaii, which is Shirley Temple’s most obvious and influential trait. Kawaii is, more or less, Japanese for “cute” and it is a word much used about the child characters in anime – the ones with big eyes and small mouths. Historically it seems very likely that Temple, the star, had at least some visual influence on the postwar Japanese representation of childish innocence and virtue, as did Mickey Mouse and certain of his predecessors. At any rate, one of the key markers of kawaii is its artificiality, its “monstrosity”. Kawaii cute is not “natural cute”. It is manufactured, drawn, sculpted, performed: first the expression, then the content. Kawaii makes the point that those who have it are not to be confused with real human beings.

In Wee Willie Winkie kawaii is visually, experientially, what sets Priscilla apart from everyone else (most especially from Mott, who fails singularly to be cute). It is possible that Ford and McLaglen may have intended us to think that MacDuff is cute too: he certainly resembles some of the large, stupid and clumsy characters in American cartoons and Japanese anime. However, if that is the intention, I don’t believe that it has been achieved. McLaglen is far cuter in some of the scenes in Hangman’s House, even arguably in The Informer.

This exchange, which is at least a little cute, is as good as it gets for McLaglen.

While it is clear that Priscilla’s hold over MacDuff, and virtually everyone else in the regiment (not excluding the Colonel) is her kawaii, Khoda Khan seems to be more impressed by her sense of justice. She cannot charm him as she can her grandfather. Khoda Khan’s followers, on the other hand, laugh at her because she is a child speaking as though she were a grown-up, which is what the kawaii children in anime often do. They see this as a mistake rather than an integral part of the inhuman thing she is.

At the same time as it is concerned with detailed expositions of Temple’s kawaii actions, the film is representing regimental life as a hermetic world of its own, built on slightly opaque rituals and strange happenings. It seems that the regiment’s isolation is a source of the strength and virtue of its military life. Soldiering is different. It is even different from the culture that spawned it, represented by the colonialist and petty provincial attitudes of some of the officers and their families. Soldiers on foreign soil are, after all, doubly outcast: first, they are cast out of home; second, they are outcast from where they now live. Nietzsche claims that frontier soldiers are scapegoats stained by the very task that society employs them to do, and the popular Japanese figure of the ronin is often deployed in narratives which explore a similar idea. It is interesting, and à propos, that often in anime kawaii children take on the roles of ronin.

Not all of the ways in which Priscilla and the regiment articulate their distance from the all-too-human world are cute, however. Among the things Priscilla observes with some puzzlement in the cantonment is MacDuff knocking out a soldier during a boxing lesson. After he has landed his punch, he spots her and goes over to her. She shuns him. However, she is only avoiding him because they have been ordered not to fraternise any more, not because she is in any way upset by the violence she has just witnessed.

When Mohammet Dihn, almost as an afterthought, is pitched over the side of Khoda Khan’s stronghold, laughing maniacally, Priscilla’s reaction is to look on expressionlessly and say, “Well, Mr. Dihn!”

One of the film’s most emotional scenes seems to suggest a similarly inhuman possibility. The wounded MacDuff is dying and Priscilla wants to see him. After some hushed consultation she is admitted to the bedside. After a brief exchange, MacDuff asks her to sing him “the song once more”, and she sings “Auld Lang Syne”. MacDuff quietly dies while she is singing, and she leaves completely unaware of what has happened.

It is one of my earliest memories of an unhealthy tendency to deconstructive criticism that when I first saw this scene I thought it was clear that Priscilla had, like a shaman, sung the Sergeant to death. Actually, I put it somewhat differently: Shirley Temple had sung Victor McLaglen to death. This was because I wanted to insert the scene into a largely imaginary narrative in which John Ford, irritated beyond measure by working with a notoriously difficult brat (who, I fantasised, had bitten him on the set), had devised this scene as his revenge. Since that time I have been surprised that this interpretation of the scene has not become the common one, and it may well be that the whole of this elaborate byplay on kawaii and ronin and inhumanity and outcasts has been devised so as to make a solid critical framework for my deviant understanding.[12]

Wee Willie Winkie is among Ford’s most seminal prewar films not only because like virtually every postwar picture it studies militarist ethos, but also because it grasps the paradox that one must grow up, one must go on, one must belong, and that this is good, even though thereby one’s conscience is arrogated and one is inculpated in collective evil. The future is to be entered into willingly. (162)

This is what Gallagher writes in his summation of the film. I wonder: it seems to me that Wee Willie Winkie is quite utopic in its rejection of the idea of collective evil, at least in times to come. The celebratory ending of the film is surely intended as a sign of a better society in the making, much as a similar scene closes Judge Priest. Priscilla never does grow up, she never does “belong”: instead she leads. At the same time, of course, she leads from the rear, even from the opposite side. She is allied with the common soldiers and with the rebels, Khoda Khan and Mohammet Dihn (if only by virtue of the fact that he twice acts as her helper). She trains as a soldier, not as an officer, understands the regiment as soldiers do, not as the Colonel and Coppy do. She treats those she likes with strict impartiality, and she likes almost everyone (“Well, Mr. Dihn!”). Her conscience is clean and likely to stay that way.

At the same time, the conscience of the rest of the world is not. War, its inescapable guilt and hope, seems to be a condition of Ford’s vision. What is recognised by Ford’s films is precisely the changing condition of the affairs of the world (that is, history), and this unceasing change finds its most dramatic and visible expression in war. Far from being always and forever an evil-but-necessary agent of change, war is a symptom of the inevitable change of history. What makes war emblematic is the military: those who are engaged in fighting the war and therefore are removed, at a distance, from society in general – outsiders. And what makes outsiders so important is the possibility that they, like a wonder child, may find a new and better way of making a community, if only in a brief glimpse.

The finale of the film reminds me of the last chapters of Frank L. Baum’s Oz books or the endings of musicals. All the survivors (and the spirits of the good people who have not survived) are gathered together for a big party with music and ritual that lifts the heart and a roll call of the principals. In this case, however, the finale is also a celebration of the regiment. In one sense this celebration takes place because Priscilla has (been) returned to the regiment; in another it takes place because the regiment, through Priscilla, has been able to overcome irreconcilable cultural differences. But, I think, in a rather more important sense the finale tells us that the regiment – and Priscilla now reinstated within it – is itself the embodiment of that higher reconciliation, the culture that exists outside all other cultures, the legion that contains multitudes.

Fan service. Honi soit qui mal y pense.

Shutters

Throughout the film runs a visual motif of shutters or blinds, which often seem to isolate only those who can see something other than what is normal in the circumstances. These figurative images arise “naturally” from the film’s imagined landscape: India in the heat of summer. Blinds and shadows can be found in the background and at the edges of scene after scene. But after a certain point their presence is remarked on, pushed before our eyes: they become crucial elements in the sense the film is making. The catalogue below is intended only to alert viewers to certain ways in which these images are handled; it is by no means exhaustive.

I would also like this list to stand for some of what Ford’s direction brings to Wee Willie Winkie, which has not been a central concern of what I have written above.

Priscilla is introduced as an observer, slid on to the screen from the right, looking out of the window of her train compartment, separated from what she sees by an invisible glass screen. Reflections move across the pane. In the carriage with her mother there are vertical shadows and occasionally a shadow flicks horizontally across the scene. These fleeting and receding images are only hints of what is to come.

Inside the coach on the way to the cantonment: panels and the vehicle’s sparse structure separate the passengers from what is around them in a variation of the railway carriage at the beginning of the film.

Stripes. Priscilla and Joyce lit from right. Striped shadow of blinds over both their bodies and faces, making obvious Priscilla’s striped shirt and the stripes on Joyce’s travelling dress. This point marks the beginning of the film’s more obvious use of striation imagery

|

|

| Coppy and Joyce. Taking tea in Raj Pore. Observing the ball as they begin to acknowledge their mutual love. | |

|

|

| During Khoda Khan’s imprisonment he is shown facing outward behind his barred window as well as with the shadows of bars over him. | |

Priscilla brings on MacDuff’s death. Her somewhat illicit visit to Khoda Khan in gaol, which had lead to his escape, was a precursor of this mission of mercy.

The Colonel at breakfast the morning after Priscilla’s clandestine flight to Khoda Khan.

Priscilla looks out through the slatted shades of Khoda Khan’s courtyard as the Patans prepare to meet (and probably destroy) the regiment – but then she runs through those barred blinds to become part of what is going on (during the attack on the cantonment she hid under her bed, only emerging when it was over).

Endnotes

[1] Andrew Sarris, “The American Cinema”, Film Culture No. 28 (Spring 1963), p. 4.

[2] Tag Gallagher, John Ford: The Man and his Movies, rev. ed. (2007), pp. 160-164. Available online athttp://www.scribd.com/doc/1556055/John-Ford-The-Man-and-his-Movies. Other citations from this book are in the form of page numbers in the main text.

[3] I can’t resist adding a note about the oddity of both of these “collections”. The first set of Rogers’ films comprised the last four of his films that were released, all from 1935: Life Begins at Forty (George Marshall), Doubting Thomas (David Butler), Steamboat Round the Bend, and In Old Kentucky (George Marshall). The second set contained what might be charitably considered a dog’s breakfast of Rogers’ features made between 1931 and 1934: Ambassador Bill (Sam Taylor 1931), Too Busy to Work (John Blystone 1932), Mr. Skitch(James Cruze 1933), and David Harum (James Cruze 1934). (They Had to See Paris 1929, Rogers’ first talking feature, directed by Frank Borzage, is included in the Murnau, Borzage and Fox set). Lightnin’ (Henry King 1930), A Connecticut Yankee (David Butler 1931), State Fair (Henry King 1933) and The County Chairman(John Blystone 1935) remain unreleased. The 18 Shirley Temple films thus far released in the 6 volumes of the Twentieth-Century Fox DVD collection do not include Little Miss Marker (Alexander Hall 1934), Our Little Girl(John Robertson 1935) and Poor Little Rich Girl (Irving Cummings 1936), presumably awaiting volume 7.

[4] The screenplay of Wee Willie Winkie is credited to Julien Josephson and Ernest Pascal. These two must have been considered top screenwriters, at least if you judge by their screen credits. They had written, separately and together, many of Fox’s A-list historical movies and thus might be expected to be adroit and swift researchers as well as canny plotters. However, nothing I have found suggests that either or both, more than anyone else (Ford, for example), would have been responsible for so altering Kipling’s story.

[5] Joyce is not the only independently minded woman portrayed positively in the film: Mrs. MacMonachie (Mary Forbes), a character not imagined by Kipling, is too.

[6] I am quite aware that Irish regiments also wore kilts, but I am pretty certain that even if Zanuck and the screenwriters were willing to condone showing such a thing, Ford would have opposed it. He would not have liked showing the Irish as colonial collaborators in India and, very possibly, would not have wanted to show Irish characters in skirts (although I imagine he quite enjoyed putting McLaglen in them).

[7] Readers thinking of Graham Greene at this point ought to be ashamed of themselves.

[8] The reference here is to the work of Octave Mannoni, specifically to Prospero and Caliban, a book which I do not take as simply as it may appear in this passage.

[9] Relax, I am not going to try to make a big deal of this coincidence. I just want to point out that in certain ways the history of Afghanistan is rather in advance of where you perhaps thought it might be. Seehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soraya_Tarzi

[10] Again I urge you not, not to think of Graham Greene.

[11] Andrew Sarris, The John Ford Movie Mystery (London: Secker & Warburg, 1976), p. 76.

[12] Now you know why I have been urging you to ignore Graham Greene.

Created on: Saturday, 28 August 2010