Marius Sestier holding a stereo viewer.

Postcard. Marius Sestier Collection. National Film and Sound Archive.

Courtesy Mme Petitbois and Messrs Sestier and Jeune.

Patineur Grotesque (Australia 1896), although filmed in Melbourne, was unknown in Australia until recently. The film was found and preserved by the Magyar Nemzeti Filmarchivum (the Hungarian National Film Archive) in 1966 but was not identified as a film produced in Australia. It was during the production of the 1996 BIFI (Bibliothèque du Film) publication ‘La Production Cinématographe des Frères Lumière’ that the film was listed as part of Marius Sestier’s work in Australia. In 2005 Coralie Martin, an intern of the National Film and Sound Archive‘s Scholarly and Academic Research program, assessed the NFSA’s holdings of frères Lumière films against the holdings of the Centre National de la Cinématographie (CNC) in France. Coralie identified two films made in Australia by Lumière representative Marius Sestier which were not in the NFSA’s Collection. The NFSA undertook negotiations with the CNC for copies of the films and they arrived in May 2006. One film was from the Melbourne Cup Carnival Series shot in Melbourne in 1896 and identified as Weighing in for the Cup, and the other was of a burlesque (comic) roller skater, also made in 1896 but unknown to NFSA curators as there has been no previous mention of this film in Australia. For further information about the work currently undertaken by the NFSA on the life and work of Marius Sestier, please go to http://www.nfsa.gov.au/the_collection/marius-sestier-collection.html

……

Marius Sestier, a pharmacist and representative of the frères Lumière to India and Australia in 1896, shot Patineur Grotesque in late October of that same year, and, oddly enough, it was never screened here despite having been screened elsewhere in the world in 1897. The film’s recent discovery and release by the National Film and Sound Archive in March 2010 has inevitably instigated further research. For not only is Patineur Grotesque now believed to be Australia’s earliest surviving film, it also provides an opportunity to reassess the predominant understanding of the first days of cinema in Australia. This essay examines the Australian theatrical milieu in which Sestier had to operate in and offers an interpretation of the circumstances as to why Sestier decided to film Patineur Grotesque and why its existence has not been known in Australia for over a century.

When Marius Sestier and his wife, Marie-Louise Sestier, arrived in Australia in September 1896, they were surprised to discover that they were not the first to bring a Cinématographe to these shores. The Lumière Cinématographe, which was typically the first projecting apparatus wherever it opened in the world, was in Australia the third projecting machine in operation at that time and one of five within the following six weeks of their arrival. With the exception of Edison’s Vitascope, the other four were branded as a “Cinematographe”.[1]

The Sestiers also realised that some of form of immediate action had to be taken to secure both the integrity and commercial viability of the Lumière Cinématographe. The global introduction of the projected moving image had already grabbed Australia’s attention approximately a month earlier when Harry Rickards, the English-born Australian theatrical entrepreneur, presented “The Cinematographe” as part of an act by illusionist and magician Carl Hertz at Harry Rickards’ Melbourne Opera House on 17 August 1896. Based on promotional strategies employed in Bombay, where the Lumière Cinématographe had captivated audiences and enjoyed the premiere position as a theatrical attraction since early July, the Sestiers were undoubtedly expecting to repeat that same success in Australia. The presentation by Harry Rickards would, however, force the Sestiers to significantly reconsider the approach to their Australian seasons.[2]

Australia’s first exposure to the “Cinematographe” came about purely by chance. According to London-based George Musgrove, theatrical manager and entrepreneur, in a letter to his business partner J. C. Williamson, Rickards had been in London earlier in the year where he booked Carl Hertz at a fee of £90 per week on the basis of his previous success in Australia. Musgrove also reported that

Hertz had nothing new to offer the Australian public – and certainly not a Cinématographe.[3]

Hertz recalls in his biography that just prior to leaving for Australia he approached Felicien Trewey, the frères Lumière representative in London, to buy the Lumière Cinématographe. Trewey adamantly refused because he was not authorised to sell the Lumière Cinématographe to anyone. But persistent in his quest to exploit the novelty of the “Cinématographe”, Hertz bought an R.W. Paul Theatrograph the day before he left England on 28 March 1896 and referred to it as “The Cinematographe” for his tours to South Africa and Australia. He claimed he bought one of only two machines from the British inventor Robert W. Paul.

“He [R.W. Paul] took me [Hertz] on to the stage and showed me the whole working of the machine … We were there for over an hour, during which I kept on pressing him to let me have one of the machines. Finally, I said: “Look here! I am going to take one of these machines with me now.”

And with that, I took out £100 in notes, put them into his hand, got a screw driver … I had one of the machines unscrewed from the floor … The next day I sailed for South Africa on the Norman with the first cinematograph which had ever left England”[4]

Hertz’s illusions and magic act opened on Saturday, 15 August 1896 at the Melbourne Opera House and it was on the Monday, 17 August, after the main show, that Hertz presented “The Cinematographe”. Press coverage and the public’s reaction to the new invention were immense, within the week Rickards decided to headline it above Carl Hertz, and “The Cinematographe” remained the top entertainment attraction for more than a month. As reported by The Bulletin, “Rickards is bound to make the most of his flourishing monopoly …”[5] Rickards had unexpectedly hit the jackpot and he was indeed determined to keep it.

This was the setting when the Sestiers arrived in Australia aboard the Messageries Maritime steamer, “Polynésien”, on 9 September 1896. The steamer first docked at Albany before docking in Melbourne on its way to Sydney, which is where the Sestiers planned to begin their Australian tour of the Lumière Cinématographe. On 14 September the “Polynésien” left Melbourne for Sydney and among the new passengers was Harry Rickards, along with his wife and daughters. Rickards was on his way to Sydney to open “The Cinematographe” at the Tivoli. That Rickards and Sestier met on board is a matter of conjecture. But that Rickards heard the Lumière Cinématographe was on board is highly probable given that the Sestiers had used it to entertain fellow passengers throughout the journey from Colombo, the news of which was reported in Australian dailies.[6]

Moreover, the temptation by fellow passengers to inform the famous theatrical entrepreneur of this new device for viewing pictures would have been considerable. What followed in Sydney tends to suggest that Rickards may have perceived a threat to his cash cow and, as a consequence, felt he had to put his guard up against this new competitor.

Rickards’ plan for “The Cinematographe” was to simultaneously exploit it in Melbourne and Sydney. Carl Hertz’s tour had always been planned to include Sydney, but the move from Melbourne was put off at least once, apparently due to public demand. But it was more likely because Rickards awaited the arrival of another machine, “The Second Edition”, as he would call it.[7] Hertz completed his season in Melbourne while Rickards left for Sydney on the “Polynésien”. On 17 September Rickards placed an “Announcement Extraordinary” in The Sydney Morning Herald to promote the opening of “The Cinematographe” for Saturday, 19 September at the Tivoli, with Hertz to open on the following Monday. Even though in his advertising campaigns Rickards had already split “The Cinematographe” from Hertz’s act, it is uncertain whether or not Rickards intended to wait for Hertz’s arrival before making this announcement, as an earlier press report had indicated the two would appear together: “Carl Hertz…make his debut at the Tivoli Company, when the cinematographe will be placed on the stage.” [8] ; or perhaps he felt the presence of the Lumière Cinématographe to be so great a threat that it would spoil his premiere if he did wait for Hertz.

Rickards’ presentation would be the first Sydney public exhibition of this new projecting apparatus and anticipation would have been high across the theatrical world as well as among the general public. For almost a month Sydneysiders had been reading news reports from Melbourne about this marvellous invention and were eager for the experience. For the Sestiers, however, the announcement must have been a complete surprise. As the official frères Lumière representative to Australia, Marius Sestier was the only person authorised to use the word Cinématographe. Yet there it was, advertised in a major daily newspaper by someone else! Something was definitely amiss and that gave the Sestiers cause to investigate further.

On Saturday 19 September, as part of an excited Tivoli audience, the Sestiers spent 8 shillings for the evening’s entertainment to size up the competition.[9] As was expected, the audience’s reaction to Rickards’ “The Cinematographe” was tremendous and its first public screening in Sydney was a huge success. But what was obvious to the Sestiers was that Rickards’ Cinematographe was not a Lumière Cinématographe. As there was no projection booth in the Tivoli the projector would have been, as it was in Melbourne, on view and placed within the audience, making it obvious to the Sestiers that it was a different machine. As well, the films were not frères Lumière titles and were fainter and indistinct by comparison to the Lumière image, which was steadier, larger and brighter. Harry Rickards, perhaps unwittingly, was trading on the reputation of the Lumière Cinématographe while actually presenting the Theatrograph.

The Sestiers now had an unexpected advantage in having seen their rival’s program and witnessed the audience’s reaction. The Sydney show was a repeat of the first Melbourne program and was a collection of R.W. Paul’s earliest films. Most were produced initially for the Edison Kinetoscope but then reprinted for use on the Theatrograph without the benefit of a negative, making them indistinct and causing them to flicker when projected onto a screen. These first films included a seascape, most likely Rough Seas at Dover (1895); horse racing, in Kempton Park Races (1895); and military reviews, which made up a program not so dissimilar from a frères Lumière program. But there was also an emphasis on comic and theatrical scenes, a speciality of the Kinetoscope and of Paul’s Theatrograph, including a skirt dancer (The Butterfly Dance, originally an Edison Kinetoscope film) and a scene from the American production of the highly popular play Trilby. The real highlight of the night was, according to a review, a scene on London’s Westminster Bridge when a man crossing it turns his head towards the camera, apparently in response to a call from the audience.

Although the Sestiers knew they had a superior product, it was evident they had to change their promotional strategy and needed to consider what they were up against. Uppermost in their minds would have been the popularity of the Rickards’ presentation at the Tivoli; that the R.W. Paul “Cinematographe” was now entrenched in the public’s mind as the benchmark; and the implication of the use of the word “Cinématographe”, which the Lumières had patented world wide.[10]

On the morning of Monday, 21 September, the Sestiers embarked on a new strategy and sent a cable to the frères Lumière in Lyon alerting them that Australia was going to prove unique in that the Lumière Cinématographe’s premiere position was already taken. Sestier sought their advice and also ordered the latest films:

Concurrent usurpant pour Cinématographe. Cablez orders. Expediez nouveauties. Sestier [11]

Sestier’s first advertisement for the Lumière Cinématographe in Australia.

Daily Telegraph, 22 September 1896.

While waiting for a reply, the Sestiers took the next step in establishing the superiority of the Lumière Cinématographe by arranging for a notice in a major newspaper. In Bombay their approach to advertising the Lumière Cinématographe was to stress the scientific nature and wonder of this new apparatus which was consistent with what was done elsewhere in the world. This approach was usurped by Rickards for “The Cinematographe” and the Sestiers realised that Australians were already impressed by, and engaged with, this new technology. Their new strategy emphasised the differences from all other Cinematographes, gave authority and standing to Marius Sestier as a representative of Auguste and Louis Lumière, substantiated the Lumière Cinématographe’s international provenance, and asserted its significance as the only authentic Cinématographe. The announcement appeared on 22 September 1896 in Sydney’s Daily Telegraph and was placed above that of Rickards’ advertisement for “The Cinematographe” at the Tivoli Theatre. The notice immediately hit the target by challenging Rickards’ integrity.

The Sestiers’ strategy was effective and the press picked up on the idea of “authentic and authorised” with varying degrees of comprehension: “‘only authentic Cinematographe’ (whatever that may mean)…”[12]

It also proved to be audacious and risky in light of the reply they received from the frères Lumière on 24 September, which insisted that such usurping was impossible to prevent. The Sestiers continued to press the point over ‘exclusivity’, which they perceived to be the key to their success, not to mention a thorn in their rival’s side. To reinforce their strategy the Sestiers replied to the Lumières requesting they be given exclusivity for all of Australia before their Australian debut on 28 September. The reply received on the 27 September gave Marius Sestier exclusivity until May 1897, the month the Sestiers were scheduled to return home.[13]

On 28 September the Sestiers opened the Salon Lumière at 237 Pitt Street in Sydney where recently vacated auction rooms provided a commodious space for audience and projection. For their first program, selected from the 150 titles brought with them, the Sestiers had heeded their experience at the Tivoli earlier in the month and included three comic films (A Baby’s Quarrel, A Game of Cards, and Watering the Garden), two military scenes (The Cuirassiers and Parade of the Guards), a seascape (Sea Bathing), two theatrical scenes (The Hat Trick and the Empire Theatre in London), plus Leaving the Lumière Factory, The Serpent, Demolition of a Wall and Arrival of the Paris Express. This was an expansion of their opening season in Bombay in early July 1896 when they opened with six films typical of the frères Lumière standard first program. The public and press response was exceptional with several reports of queues lining up across the street.[14]

The two “graphes” competed for the Sydney audience. Salon Lumière was open up to twelve hours almost every day and ran shows every half hour. This enabled patrons to attend whenever they liked, and as the program changed regularly they were always able to see something new along with the favourites. At the Tivoli, Rickards’ show was only open in the evening, regulating audience attendance and, unlike the Salon Lumière, featured other entertainers. Rickards’ repertoire of films was smaller but in early October he was able to offer coloured films, which had been coloured frame by frame in R.W. Paul’s laboratory.

With this development Marius Sestier asserted his authority and upped the ante. Armed with the Lumières’ confirmation of his request for exclusivity, a paragraph in The Bulletin, accompanied by a photograph of Marius Sestier, emphasised that Sestier was “the sole representative in Australasia of the Lumière Cinématographe” and hinted at the potential for legal action.

The name “Cinématographe” seems to have been devised and registered by the Messers Lumière before there were any rival machines in the field. Sestier, their agent in charge of the newly arrived “Cine,” is said to carry power of attorney to fight the question re infringement of title, which is undoubtedly an important consideration as things are going.[15]

While this notice encompassed all who used the word Cinematographe to describe the apparatus with which they projected moving images, it was also aimed squarely at Rickards, and could have prompted a meeting between Rickards, Hertz and Sestier. In such a meeting an agreement may have been reached in which Hertz would no longer present the Cinematographe in Australia and Rickards would retain only the Melbourne market given that he had already captured it. Marius Sestier was to hold exclusivity, as far as possible, in all Australian states except Melbourne, where he performed but did not open a venue. There would also have been some agreement about ceasing to use the word Cinematographe. What followed may certainly have been in Rickards’ tour plans all along, or it could have resulted from such a meeting, where patent and territories would most definitely have been the main points of discussion.

Rickards closed “The Cinematographe” and Carl Hertz at the Tivoli in Sydney on 14 October. That date in itself would be meaningless were it not for the fact that it happened to fall on a Wednesday, which was not the usual day for closing highly lucrative shows. Carl Hertz continued his Australian tour for Rickards as a master illusionist and prestidigateur without “The Cinematographe”, but with one exception. After Sydney, Hertz arrived in Brisbane and performed at the Opera House on the closing night of the Rickards’ season before heading to Rockhampton, where, on the last two nights of that season, he presented “The Cinematographe”. In a review of his show in Rockhampton, Hertz claimed to have made improvements to the projector.[16]

When in Adelaide for the Christmas and January seasons, Hertz was billed under the Lumière Cinématographe presented by Marius Sestier at the Theatre Royal. After a short return season in Sydney, Hertz acquired a new “Cinematographe” and left for a lengthy and profitable tour of New Zealand under the management of Edwin Geach. Upon his return to Australia in July 1897, almost two months after the Sestiers had returned to France, Hertz toured Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth, the goldfields of Western Australia, and Hobart, and in all of his shows he presented “The Cinematographe”. His last shows were in the town of Zeehan in Tasmania while he waited for good weather to sail for England. He left Australia in the early days of December 1897.[17]

In Melbourne, where the R.W. Paul Theatrograph had been running almost continuously, Rickards persisted in calling it “The Cinematographe” but did not open it in any of his other capital city venues. However, in November 1896 he leased “The Cinematographe” to Philip Newbury of the Newbury-Spada Company who toured regional Victoria, Hobart and regional Tasmania, giving these areas their first exposure to moving pictures.[18]

The closing of Rickards’ show at the Tivoli on 14 October left Marius Sestier with just over two weeks as Sydney’s sole exhibitor of the Cinématographe before he departed for Melbourne where he was contracted to appear as a “speciality” in the J.C. Williamson pantomime spectacular Djin-Djin the Japanese Bogey-Man. But Rickards and Hertz did not simply pack up and go.

One of the films screened at the Tivoli was R.W. Paul’s The Derby, a film of the famous British horserace, the Epsom Derby, which had run that past June and in which the Prince of Wales’ horse Persimmon won. Newspapers reported that Paul had filmed, processed and screened it that same night at the Alhambra in London giving it the reputation of being the first filmed news story. The film was a hit when it headlined in both Sydney and Melbourne, where the population was gearing up for the Melbourne Cup Carnival. Earlier in the month a journalist had suggested that the filming of the Melbourne Cup would be a good idea. On 12 October Carl Hertz said he would soon have a camera and James McMahon, who had been presenting the “Cinematographe” in Brisbane, announced he had a camera and both declared they would film the forthcoming Melbourne Cup.[19]

The frères Lumière expected that Marius Sestier would make films in Australia and the imperative to do so was intensified with this new challenge. On the eve of his departure to Melbourne Marius Sestier, along with his business partner Henry Walter Barnett, presented Passengers Leaving the S.S. Brighton at Manly. This film not only has the reputation as their first Australian-made film, it is the first film made and screened in Australia. It was well received by the public and the filmmakers promised to return from Melbourne with more locally-made films that would be toured in London and Paris. Sestier and Barnett made and screened around 19 Australian films. Four films were made in Sydney: Passengers Leaving the S.S. Brighton at Manly; two films of NSW Horse Artillery at Drill, Victoria Barracks, Sydney; and George Street near the General Post Office. In Melbourne they made 15 films: Patineur Grotesque and the remaining 14 comprised of the Melbourne Cup Carnival Series of Arrival of Train – Hill Platform, The Lawn Near the Bandstand, Arrival of H.E. Lord Brassey and Suite, The Saddling Paddock, Finish of Hurdle Race – Cup Day, Weighing-out for the Cup, Finish of the Race, Weighing-in for the Cup, Lady Brassey placing the Blue Ribbon on “Newhaven”, Near the Grandstand, Afternoon Tea under the Awning, “Newhaven” his Trainer W. Hickenbotham and Jockey Gardiner, Derby Day – The Betting Ring, and Decoration of Newhaven-Derby Winner.[20] Despite their plans to film the Melbourne Cup, no such Australian made films are known to have been made by Carl Hertz, Harry Rickards, James McMahon or their employees.

When the Sestiers arrived in Melbourne they were confronted with three other projection systems. The city was inundated with “graphes,” as the press seemed to have lamented:

Melbourne – will be chock-full of cinematographes before the week has ended. No 1 is to be found at the Opera House; No 2, which is just out from Paris, is on The Block; No 3, Edison’s Vitascope, is at the Athenaeum; whilst the last, the Lumière, is to run with the big “Djin-Djin” show at the Princess’ Theatre from Saturday next.[21]

Magnificent as is the exhibition of M. Marius Sestier’s Lumiere Cinématographe, one is in momentary doubt whether the cinematographe ought to be classed a novelty this Cup time. It appears as necessary to the completeness of a theatrical entertainment as the orchestra or the printed programme. Just amazement would have been excited had Messrs. Williamson and Musgrove dared to open their house without the cinematographe. We have the Princess’s Theatre with “Djin Djin” and the cinematographe; the Theatre Royal with Henry V., and the new invention appears upon the stage before Harfleur or the Battle of Agincourt can be so much as thought of. At the Opera House the cinematographe is still in possession. Under another name – the vitascope – it has invaded the Athenaeum-hall; lower down Collins-street it has broken out also, making a temporary home in the premises upon the block. The country visitor who returns home from this racing carnival still in ignorance of the marvels of the cinematographe must have gone nowhere and seen nothing.[22]

The “Perfected Cinematographe” was showing on Collins Street and appearing in the pre-show of George Rignold’s Henry V. Also on Collins Street at The Athenaeum was Edison’s Vitascope. Despite any agreement that may have been made in Sydney, Rickards was still presenting his projector as “The Cinematographe”, but had the word placed less conspicuously in his advertising.[23]

The word Cinematographe, instead of being exclusive, was applied by operators and a confused press to anything that projected moving images. Even in Sydney where the Sestiers had insisted on their exclusivity and, presumably, struck a deal with other theatrical operators, James McMahon had moved from Brisbane with his “Cinematographe” into 237 Pitt Street, the original home of Sestier’s Salon Lumière in Australia. Indeed, during this time a “Cinematographe” was always on show somewhere in Australia. Even though the Lumière Cinematographe was recognised as the best, the Sestiers must have been frustrated that others – especially Harry Rickards – should capitalise on the profile and reputation of the Lumière Cinématographe. Marius Sestier, a good-natured and caring man with a twinkle in his eye and a cheeky sense of humour, parried with the film Patineur Grotesque.[24]

The gold “bust” of the early 1890s and, in 1896, the beginning of a ten-year drought put financial stress on Melbourne’s legitimate theatre world. Already by 1895 J.C. Williamson’s company, nicknamed “the Firm”, was in financial trouble. Without funds to import top shows, the difficulty in finding good available acts, and with the failure of some recent shows, Williamson and his partner George Musgrove believed they might have to close, at one stage asking their company to accept a major pay cut.[25] Good new Australian material was almost non-existent and so Williamson, with librettist Bert Royale and composer Leon Caron, wrote and produced a pantomime spectacular titled Djin Djin the Japanese Bogey Man. The pantomime ran for months at the Princess Theatre but its success only just brought the books into balance. By mid 1896 Williamson and London-based Musgrove were discussing what they would present for Christmas that year. Still in financial straits, the lack of funds preventing them from being able to pay for top acts and plays, they needed a hit to put them back in the black. As time was running out they settled on a revival of Djin Djin the Japanese Bogey Man, re-working the songs and costumes, and employing a new cast and new “specialities”. Djin Djin opened on the evening of 31 October 1896, Derby Day, with the fate of the company riding on it.

Marius Sestier and the Lumière Cinématographe was one of the new “specialities”, in fact was the main drawcard for Djin Djin. When exactly Williamson signed Marius Sestier to appear is not clear but Williamson, returned to Sydney for the Scott Inglis-Yda Hamilton wedding where he was giving away the bride, one of the Potter-Bellew Company, and for the opening of his new show The Goodwin Comedy Season, featuring Nat Goodwin in mid September. On the afternoon of Saturday 26 September Williamson had given, at no charge, the use of the Lyceum Theatre to the Sestiers for an invited guests and press only preview. Subsequent to that Williamson’s Sydney theatre manager, Charles Westmacott, together with the photographer Henry Walter Barnett, had a managerial role in the Salon Lumière.[26]

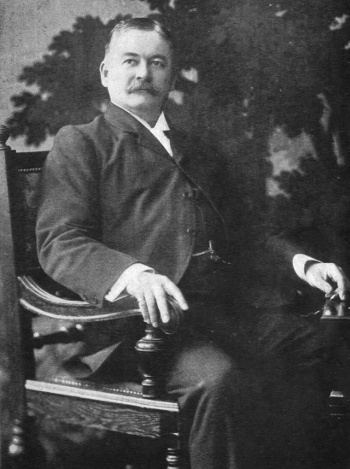

Marius Sestier, 1896. [Photo H. Walter Barnett]

Marius Sestier Collection, National Film and Sound Archive.

Courtesy Mme Petitbois, Messrs Sestier and Jeune.

On 31 October Marius Sestier was in Melbourne for his performance in Djin-Djin where he was to appear at the end of Act Three, Scene One when the Shogun’s enchanted son is restored to him and in celebration ‘A Grand Speciality Entertainment’ is given prior to heading off to Fairy Land.[27] Earlier in the day Sestier and Barnett had filmed the proceedings of the Melbourne Cup Carnival’s Derby Day at Flemington. They would return to Flemington on the following Tuesday to film the Melbourne Cup.

Patineur Grotesque, a film of a burlesque roller skater, was made between 29 October and 2 November. It was never screened in Australia but premiered in France in February 1897. In the cable received from the frères Lumière in which Sestier was granted exclusivity, Sestier was also asked to film only “the best subjects”. With a limited number of negatives at hand, Sestier and Barnett would have carefully considered a selection of subjects for filming, and their intention to film the internationally known Melbourne Cup Carnival certainly fitted that bill. But Patineur Grotesque, although in keeping with the Lumière convention of filming theatrical acts, does not immediately appear to meet the criteria of “best subjects”. At first glance the film seems fairly unremarkable, inoffensive, an everyday street act caught on film. However there are elements that belie this immediate impression and which reveal an insult.[28]

The film shows a man on roller skates dressed in a suit with only the top button done up. He is also wearing a hat and smoking a cigar. He is situated in the foreground and centrally within the frame. The action takes place in a park and behind him is a semi-circle of spectators watching him and the camera. Behind the spectators, trees and buildings can be seen, and a small amount of traffic on a road that separates the park and the buildings is also visible. The skater performs his act in which he skates around in comedic fashion, tripping and falling. He performs to his audience, ignoring the camera for the most part, except for one moment when, with his back towards the camera, he lifts his coat tails to reveal an upright white hand motif on his bottom, which he thrusts at the camera.

While the location cannot be determined precisely, a likely locale would have been Melbourne’s Yarra Park in Jolimont, on Wellington Parade near Jolimont Terrace. In 1896 this was a large park in which was located the Scotch College Cricket Ground, the Melbourne Cricket Ground and the Richmond Cricket Ground. Its layout of paths also suggests a likeness to what is seen in the film. Moreover, Yarra Park was close to where the Sestiers were situated at the Spring Street end of Melbourne for both their accommodation and purposes of work.[29]

Also close by was a skating rink, Wagner and Beyer, which had opened on 5 October 1896 at 184 Exhibition Street between Little Bourke and Bourke Streets.[30] In 1896, roller-skating enjoyed a huge resurgence throughout Australia and New Zealand and became quite a craze. It was quite common for rinks and places like Aquariums or other large amusement houses to include trick, comic or burlesque skaters performing nearby to attract patrons. Skating also featured on stage where “champion” skaters like Fred Norris, Professor Sid Frith, Harry Steele, and Harry Williams would perform.

Identification of the skater in Patineur Grotesque seems near impossible but he may well have been associated with either the new rink or with one of the shows in town. The skater is made up as a bearded but balding man and is smoking a large cigar. He wears a hat that he lifts on several occasions. Under his jacket he wears a plaid waistcoat with a fob watch in his pocket and he appears to be well padded around the torso. But the most distinctive thing about his appearance is the motif of a white hand on the seat of his pants, which he deliberately thrusts to the camera when he lifts his coat tails and appears to break wind at the camera.

Screening at Rickard’s Opera House on Bourke Street between Swanston and Russell Streets, was R.W. Paul’s Chirgwin, the “White-eyed Kaffir”, which had begun its season around the 26 September 1896. Only part of this R.W. Paul film survives today and in it Chirgwin removes his jacket to reveal a white hand motif on his rear but with the fingers pointing downwards as if cupping his buttocks. When the skater in Patineur Grotesque thrusts his bottom at the camera it is clearly the same white hand motif but with the fingers pointing upwards.[31]

The skater is certainly parodying Chirgwin and it is possible that Sestier simply found him performing in the park and filmed him. But this does not resolve why Patineur Grotesque was never publicly screened in Australia, or why the actions in the film would imply a deliberately orchestrated insult. Perhaps there were problems with film processing and developing which reportedly had occurred with other films made in Sydney by Sestier and Barnett, although, that would not account for the existence of the film today. Perhaps, too, Patineur Grotesque was thought somewhat offensive because George H. Chirgwin was due to arrive at the end of the month to star at Rickards’ Opera House.[32] The key to answering these questions lies in the translation of the title, as this film had no English release title, and was not titled until its premiere in France.

Literally translated patineur means skater and grotesque means ludicrous or ridiculous. In 19th century French, a skater was slang for con man. But the insult goes further with patineur also meaning “cultivateur en attouchements lascifs”, or in English “farmer of lewd fondlings”, or, as commonly known these days, “pimp”. Further insult is implied when the skater raises his hat, for patineur encapsulates another slang reference, that of “bonneteur”, which means con man or a stranger who ingratiates himself by lifting his hat too often to win you over.[33]

The slang nature of the title Patineur Grotesque provides an understanding as to why it was not screened in Australia. Sestier was annoyed at all and sundry who profited by usurping the name “Cinématographe”, and because he had made agreements only to see them broken, this cheeky film with its layers of humour and insult was made to vent his frustration.

J.C. Williamson. Djin Djin programme book, 1895.

Courtesy Latrobe Rare Books Collection, State Library of Victoria.

Once the film was developed and screened to a closed audience of immediate colleagues, the insult, and to whom it was directed, were very clear. In a photo of J.C. Williamson published in the Djin Djin programme book, the skater’s outfit is reminiscent of J.C. Williamson who, in the fashion of the day, often left the top button of his jacket done up as the skater does.[34] The white hand motif refers to Rickards’ film programme at the Opera House, but in having the hand centrally positioned over the skater’s bottom and with its fingers pointing upwards, was meant to produce an obvious and familiar insult – “up yours, mate!” It was most likely a wonderful moment for Rickards’ competitors, but also wise advice to Sestier to not screen it to the Australian public.

Patineur Grotesque was not screened in Australia because the caricature of Williamson insulting Rickards was not only possibly libellous, it was also unacceptable. As much as Rickards was disliked by the J.C. Williamson theatrical fraternity – Musgrove having referred to him as “a blustery ass” in letters to Williamson – Rickards was relied upon to defray their high costs of imported stars by sharing them once they were in Australia. In letters written between George Musgrove and J.C. Williamson just as the Cinematographe was exploding around the world and in Melbourne, Musgrove discusses Rickards’ plans to tread on the J.C. Williamson patch and produce a pantomime. In reaction to this, Williamson planned for his next production, which would be Djin Djin, to take the wind from Rickards’ sails by placing as many “specialities” of the sort that Rickards would usually employ in his own shows. Williamson also asked Musgrove about securing a Cinematographe. Musgrove replied that he didn’t think the Cinematographe would do what Williamson wanted it to do and he advised against taking Rickards on at his own game. They also discussed Rickards’ newest comedian, Will Crackles, whom Rickards had promised to share at the end of his six month contract. Not trusting Rickards, who had a renewal option on Crackles’ contract, Musgrove signed Crackles to play a main role in Djin-Djin. Even so, “the Firm” had to stay on the right side of Rickards to ensure Crackles would be available to them.[35]

There was already a sensitive balance between Australia’s top two theatrical entrepreneurs that Patineur Grotesque had the potential to jeopardize. But in late 1896 that balance was not tipping in favour of “The Firm” and the survival of the company was at stake. Musgrove and Williamson knew they would need to woo and sweet-talk Rickards, even if they disliked this man, for having already stepped outside of their agreement with him over Crackles. “The Firm” could not chance Rickards taking offense at Patineur Grotesque and making life difficult for them.

But no such difficulties existed elsewhere in the world and Patineur Grotesque was accepted into the first catalogue of frères Lumière films and had its first public screening in Lyon from 7 March 1897 as Melbourne: Patineur comique. Then, a few weeks later, it was renamed as Patineur Grotesque, the title it has kept for the past 114 years. As part of the frères Lumière catalogue the film was picked up and screened by other frères Lumières operators around the world. To date, research shows that the film screened in Hungary, Spain and Brazil in 1897 and in Mexico in April 1898, where it was included in their first programs of the Lumière Cinématographe. To be included in the first programs indicates that Patineur Grotesque was a success, and hit its mark as a comedy for the first shows were designed to impress the audience. (This gives some justification to the claim made by Georges Sadoul, the prolific French film historian, when in 1973, he wrote that Patineur Grotesque was the forerunner to Max Linder and Charlie Chaplin.)[36]

Consequently Patineur Grotesque, in which Sestier gives Rickards the finger, was ironically an Australian theatrical “in” joke destined to never reach Australian screens. Paradoxically, Patineur Grotesque’s superficial and simple humour, so easily translated across cultural or language barriers, was recognised by the world as a successful comedy. That Patineur Grotesque, prohibited to Australians, should be the first glimpse of Australia on film in many countries is testament to the skill of its maker, Marius Sestier.

Endnotes

[1] On 17 August 1896 Carl Hertz first presents a public preview in Melbourne of “The Cinematographe” in reality the English-made R.W. Paul Theatrograph in Table Talk 21 August 1896. On 26 September James McMahon opens in Brisbane with a projecting system advertised as the ”Cinematographe” in The Courier Mail 24 September 1896, p. 2. In Adelaide on 19 October 1896 Frank St Hill and Mr Moodie opened “The Cinematographe”, in reality an Edison projecting kinetoscope, at the Theatre Royal and Beehive Buildings as per the Express and Telegraph 19 October 1896, front page. At the Melbourne Athenaeum Edison’s Vitascope opens on 31 October 1896 according to The Age 24 October 1896 (p. 8). Also in Melbourne was “The Perfected Cinematographe” developed by Henri Joly and presented by French artist Gustave Neymark and French-born émigré photographer Albert Perier which opened on Collins Street on 26 October 1896 as per The Age October 24 1896, p. 8.

[2] Bombay Scrapbook. Marius Sestier Collection. National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. The scrapbook indicates he took his lead from Lumière Cinématographe advertisements in French and American newspapers where the emphasis was on the nature of the apparatus as a “scientific marvel”. An earlier essay, Jean-Claude Seguin, “Marius Sestier, Operateur Lumière Inde-Australie: Juillet 1896-Mai 1897,” Cinema 1895 16, June 1994, pp. 34-58, discusses Sestier’s promotional strategies in Bombay and in Australia.

[3] George Musgrove to J.C. Williamson, 23 February 1896, J.C. Williamson Collection, MS5783 Box 614, Folder 9, National Library of Australia, Canberra.

[4] Carl Hertz, A Modern Mystery Merchant: The Trials, Tricks and Travels of Carl Hertz, the Famous American Illusionist (London: Hutchinson & Co, 1924), pp. 116-120, pp. 138-159. Hertz’s first visit to Australia was for J.C. Williamson and George Musgrove in 1892; Hertz’ description of his purchase of a “Cinematographe” in 1896 when he bargained with Paul for an apparatus.

[5] The Age, 21 August 1896 – 17 September 1896. Various reviews and newspaper advertisements for Carl Hertz at Rickards’ Opera House, Melbourne; Sundry Shows. The Bulletin, 3 October 1896.

[6] 1. M.M. Polynésien passenger list. Shipping Master’s Office: Passengers Arriving in Sydney 31 August to 31 October 1896; 2. The M.M. Liner Polynésien, Daily Telegraph, 17 September 1896 p. 7; 3. Arrival of the Polynésien, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 September 1896, p. 4; 4. Le Cinématographe. Le Courrier Australien 19 September 1896, p. 3.

[7] Plays and Players, Punch, 4 September 1896; Amusements: Opera House, The Age, 5 September 1896; Amusements: Tivoli Theatre, The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 September 1896, p. 10; On and Off the Stage, Table Talk, 11 September 1896.

[8] Amusements: Tivoli Theatre, The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 September 1896, p. 10; Tivoli Theatre Announcement Extraordinary, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 September 1896, p. 2.

[9] Sestier Tournée, Marius Sestier Collection, p. [16], National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. This accounts and daily activities book records the Sestiers’ attendance at the Tivoli on the 19 September 1896.

[10] The difference in quality in the projected image between the Cinématographe and the Theatrograph at this early stage was that Hertz had acquired the Theatrograph just as R.W. Paul was at the beginning of developing his machines and process. And as, at that time, Paul had no camera to make films he was reprinting Edison kinetoscope films from a print and not a negative to fit his Theatrograph projector. Kinetoscope films were produced for a very different viewing environment that is, enclosed within a kinetoscope viewer and were also much shorter in screen time being between 20 and 40 seconds. Many of the early kinetoscope films were filmed inside and the action took place against a plain background. The frères Lumière on the other hand had already had at least a year to develop their process and refine their filmmaking. Their films were one minute in duration, were filmed outside providing visual interest – foreground, background as well as centre frame all contained movement. The size of the projected image may also have been a contributing factor as one reviewer notes the large projected image being 10ft by 12 ft, in Sydney Mail 17 October 1896, p. 801.

The Lumière Cinématographe was patented in 1895 and as each new improvement was made a subsequent patent was taken out. But the frères Lumière were not the first to call their apparatus a Cinématographe which was a machine that could shoot, develop and screen films. There is much conjecture around who was first and who patented what as in 1896 in France alone there were 129 patents taken out for similar machines which had been in development for a number of years, but at the time the frères Lumière and their operators believed they had sole rights to the word and the process having been the first to patent it. For a more lengthy discussion see Bernard Chardère, Le Roman des Lumière. (France: Editions Gallimard, 1995); Jacques Rittaud-Hutinet, Le Cinéma des Origines: Les Frères Lumière et Leurs Operateurs, (France: Editions de Champ Vallon, 1985); Georges Sadoul, L’Invention du Cinéma, (France: Editions Denoël, 1945)

Titles being screened by Rickards are listed in the newspaper advertising: Amusements: Opera House. The Age, 29 August 1896, p. 8; Amusements: Tivoli Theatre. Sydney Morning Herald, 21 September 1896, p. 2. Carl Hertz makes a claim to having bought kinetoscope films in Johannesburg and spending all night adapting them to run on the Theatrograph as the spracket-holes [sic] didn’t match, in Carl Hertz, A Modern Mystery Merchant: The Trials, Tricks and Travels of Carl Hertz, the Famous American Illusionist (London: Hutchinson & Co, 1924), pp. 144-145.

The call from the audience to the man on the screen was apparently devised in Melbourne and so one assumes that it was one of Rickards’ troupe who provided the call in Sydney to give the audience the idea, Sundry Shows, The Bulletin, 12 September 1896.

[11] Sestier Tournée, Marius Sestier Collection, p. [17], National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. Translation: Rival for Cinématographe. Cable instructions. Send new pictures immediately.

[12] Sundry Shows. The Bulletin, 3 October 1896, p. 8. In the same paragraph the journalist praises Rickards’ show and The Cinematographe.

[13] Sestier Tournée, Marius Sestier Collection, p. [17], [19], National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. Transcription of cables received by the Sestiers from the frères Lumière.

[14] Amusements: Lumiere’s Cinématographe, The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 September 1896, p. 2. In Bombay the Sestiers opened with Entry of Cinématographe, Arrival of a Train, The Sea Bath, A Demolition, Leaving the Factory, Ladies and Soldiers on Wheels, New Advertisements: Marvel of the Century. The Bombay Gazette, 7 July 1896, p. 2.

[15] Sundry Shows, The Bulletin, 10 October 1896, p. 8. The photograph was taken by Marius Sestier’s Sydney business partner Henry Walter Barnett, a high profile society and theatrical photographer and co-owner of the Falk Studio.

[16] Of course, this may simply have been due to the lack of electricity in some of these areas.

[17] Carl Hertz’ tour subsequent to his first shows at the Tivoli on Sydney: Brisbane: Amusements: Opera House, The Brisbane Courier, 13 and 17 October 1896, p. 2.; Rockhampton: Local News, The Morning Bulletin, 17 October 1896, p. 5. Amusements, Meetings: Theatre Royal, The Morning Bulletin, 19 October 1896, p. 5; Amusements. Theatre Royal. Rickards’ Tivoli Company, The Daily Northern Argus, 23 October 1896, p. 1, 3; Chartres Towers: Local and General, The North Queensland Register, 11 November 1896, p. [5]; Townsville: Shipping Departures: Franklin for southern ports, North Queensland Herald, 25 November 1896, p. 38; Maryborough: Amusements Town Hall Rickards’ New Tivoli Speciality Co., Wide Bay and Burnett News, 3 Dec 1896, p. 3. Local and General News, Wide Bay and Burnett News, 8 December 1896, p. 2; Gympie: Local and General News, Gympie Times, 10 December 1896, p. 3; Brisbane: Entertainments Opera House, The Brisbane Courier, 10 December 1897, p. 2. Opera House: Harry Rickards’s [sic] Company, The Brisbane Courier, 11 December 1896, p. 4; Melbourne: Amusements Opera House, The Age, 19 December 1896, p. 8; Adelaide: Amusements. Theatre Royal, Adelaide Advertiser, 21 December 1896, p. 2; Sydney: Palace Theatre, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 February 1897, p. 3, Amusements: Palace Theatre, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 February 1897, p. 2.; Hobart: Amusements, Lectures. Theatre Royal, The Mercury, 2 July 1897, p. 3; Melbourne: Amusements. The Athenaeum. The Argus, 9 July 1897, p. 8; Perth: Entertainments: Cremorne Theatre, The West Australian, 14 August 1897, front page; Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie in Carl Hertz, A Modern Mystery Merchant: The Trials, Tricks and Travels of Carl Hertz, the Famous American Illusionist (London: Hutchinson & Co, 1924); Entertainments: Fremantle Town Hall, The West Australian, 18 September 1897, front page. Zeehan: Zeehan News, The Mercury, 3 December 1897, p. 2.

[18] On and Off the Stage, Table Talk, 4 December 1897, p. 14; Amusements. Exhibition Theatre. The Geelong Advertiser, 8 December 1896, p. 3; Academy of Music. The Cinématographe, The Examiner, 18 December 1896, p. 4.

[19] Sundry Shows, The Bulletin, 3 October 1896; Amusements: Tivoli, Sydney Morning Herald, 12 October 1896; Amusements: The Animetograph-Denimy, The South Australian Register, 19 October 1896.

[20] The exact number of films made is inconclusive as no list of the exact titles appears to exist. It was the practice to give a film a title that was descriptive rather than interpretive, and thus it could be altered in whatever way was seen fit at the time. Hence, some of the titles such as Weighing-in for the Cup and Weighing-out for the Cup may indeed be the same film simply rephrased even though they are two different events in the course of a horse race. Similarly, Lady Brassey decorating the winner “Newhaven” may have been filmed once or twice as Newhaven won both the Derby and the Cup.

In Sestier Tournée, Marius Sestier Collection, p. [20], National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra, there is a list of the films in the order they were made but, once again, exact titles are not given; The French Cinématographe, The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 October 1896, p. 8, reveals the plan to make further films for screening in Paris and London.

[21]Greenroom Gossip, Punch (Melb), 29 October 1896, p. 355.

[22] Entertainments, The Australasian, 7 November 1896, p. 917.

[23]Amusements: Opera House, The Age, 31 October 1896, p. 12; Amusements: Opera House, The Age, 7 November 1896, p. 12.

[24]Both family and professional photographs of Marius Sestier capture this twinkle in his eye and a cheeky attitude. Two examples from his life indicate his caring nature. As a French pharmacist he was required to assist the sick and wounded almost like a paramedic does today, and in Bombay he gave free screenings to orphans who would otherwise not be able to attend.

[25] Two of the most recent shows featuring expensive imported acts had not been as successful as hoped. First, there was the American Potter-Bellew Company which undertook a long season of dramas in Melbourne at the Princess Theatre and then moved to Sydney’s Lyceum. The second was The Goodwin Comedy Season starring Nat Goodwin, an American comedian, for whom J.C.Williamson’s had put together a touring company of forty or so imported actors. Goodwin’s company performed a mix of drama and comedies did not achieve the financial reward hoped for, although good reviews were constant. Mimes and Music, Evening Post (NZ), 5 September 1896, p. 2; George Musgrove to J.C. Williamson, Letters, J.C. Williamson Collection, MS5783 Box 614, Folder 9, National Library of Australia, Canberra. The pay cut is discussed by of one of J.C. Williamson’s top managers George Tallis in his biography by Michael and Joan Tallis, The Silent Showman, (South Australia: Wakefield Press, 1999), pp. 35-36.

[26] Amusements: Lyceum Theatre, The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 September 1896, p. 10. Williamson returned from Melbourne on 3 September; A Theatrical Marriage, The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 September 1896, p. 3; Amusements: Lyceum Theatre, The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 September 1896, p. 2; Lumiere’s Cinématographe, The Town and Country Journal, 3 October 1896; Amusements: Salon Lumiere, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 September 1896, p. 2.

[27] Djin-Djin, the Japanese Bogie Man: Or, the Great Shogun who Lost his Son and the Little Princess who Found Him: A Fairy Tale of Old Japan / by Bert Royle and J.C. Williamson; music by Leon Caron; with additional numbers by H.J. Pack. Theatre Programme, 1895-6. Rare Books, State Library of Victoria.

[28] Sestier Tournée, Marius Sestier Collection, p. [39], National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. In this daily activities and accounts book a list shows the films made in Australia in the order they were made. The “Skater” is listed before the Melbourne Cup films. Patineurs Comiques as it was first called premiered in Lyon see, La Photographie Vivante, Le Passe-Temps et Le Parterre Reunis, 7 March 1897, p. 8. The film screened again in April this time with the title Patineur Grotesque see La Photographie Vivante, Le Passe-Temps et Le Parterre Reunis, 4 April 1897.

Sestier Tournée, Marius Sestier Collection, p. [19], National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. Cable stuff.

[29] The layout of Yarra Park, showing the alignment of paths can be found in the following map: Sands and McDougall Pty Ltd New Squared Map at http://nla.gov.au/nla.map-rm3030-sd-cd

[30] Amusements. Skating Rink, The Argus, 1 October 1896, p. 8. This is a very small line ad at the bottom of one of the columns.

[31] Amusements. Opera House, The Age, 26 September 1896, p. 8. Paul made two films of Chirgwin in 1896. A Filoscope version (similar to a flip book) of the only known surviving film is held at The National Museum of Photography, Film and Television in the UK. It can be viewed on the BFI DVD release R.W. Paul: The Collected Films 1895-1908.

[32] Jack Cato, The Camera in Australia. (Victoria: Georgian House, 1955) pp. 116-117. Cato relates how inexperience in developing the negatives caused films to be ruined.

Opera House: “The White-Eyed Kaffir”, The Argus, 1 December 1896, p. 6. Chirgwin’s first show was for Harry Rickards in Melbourne on 30 November.

[33] Argoji: Argot Français Classique. A slang dictionary covering several centuries. http://www.russki-mat.net/argot/Argoji.php

ScoundrelsWikiSite: Scoundrels’ Glossary. A website of slang terms for scoundrels in various languageshttp://scoundrelswiki.com/ScoundrelsGlossary.

[34] Djin-Djin, the Japanese Bogie Man: Or, the Great Shogun who Lost his Son and the Little Princess who Found Him: A Fairy Tale of Old Japan / by Bert Royle and J.C. Williamson; music by Leon Caron; with additional numbers by H.J. Pack. Theatre Programme, 1895-6. Rare Books, State Library of Victoria. Photograph of J.C. Williamson is on page [15].

[35] George Musgrove to J.C. Williamson, Letters, J.C. Williamson Collection, MS5783 Box 614, Folder 9, National Library of Australia, Canberra.

[36] Patineur Grotesque in Lyon: La Photographie Vivante, La Passe-Temps et Le Parterre Reunis, 7 March 1897, p. 8; La Photographie Vivante, La Passe-Temps et Le Parterre Reunis, 4 April 1897, p. 8. Patineur Grotesque in Rio de Janeiro: Maite Conde, Film and the Cronica: Documenting New Urban Experiences in Turn of the Century Rio de Janeiro. Luso-Brazilian Review Vol 42 No 2 (2005), p. 70; Adriano Medeiros da Rocha, Cinejornalismo Brasileiro: Uma visão pelas lentes da Carriço Film, Niteroi, 2007, p. 20, 39. In Spain: Pedro Nogales Cárdenas, Cine No Professionale e Historia Local, Capítulo 3º: Arte, pp. 160, 163; Mónica Barrientos Bueno, Inicios del cine en Sevilla (1896-1906): de la presentación en la ciudad a las exhibiciones continuadas Sevilla Secretariado de Publ., Univ. de Sevilla 2006, p. 333. In Mexico: Juan Felipe Leal, Carlos Arturo Flores Villela, Eduardo Barraza, Anales del cine en México, 1895-1911, Volume 4, Part 3. Mexico, Voyeur, 2007, p. 151.

Georges Sadoul, Histoire Generale du Cinema: L’Invention du Cinema 1832-1897. (Paris: Denoël 1973), p. 356.

Created on: Wednesday, 1 September 2010