We recognize that we are collective agents of history and that history cannot be deleted like web pages. — Angela Davis

Among the most celebrated of essay films made by the Black Audio Film Collective and directed by John Akomfrah is Handsworth Songs (1986). In this film, the narrator describes a black woman who is confronted with the remains of the 1985 Handsworth riots. She says: “The black woman gazed across the debris-ridden streets and said ‘there are no stories in the riots, only the ghosts of other stories. Look there and you can see jEnoch Powell telling us in 1969 that we don’t belong’”. This dialogue encapsulates a salient aspect of the film’s overall project in microcosm, positioning the riots within an entire history of racism enacted upon migrant populations in the streets of Britain during the post-imperial period. While the voice-over narration is explicit in its indictment of the historical past, the film is equally explicit in its refusal to visualise it, leaving the viewer to do the work of remembering or imagining Enoch Powell spouting his hateful rhetoric. What is visible in the film is the aftermath of the riots, situated as a palimpsest wherein the accumulated narratives of the past assume a spectral existence.

In this brief scene from Handsworth Songs, traces of a traumatic event are further burdened by the weight of a long history that has become difficult to see, recalling Rey Chow’s designation of ‘remains’. In her essay “Remains’ Regime Change”, Chow defines remains as “human labor that leaves its spoors”, arguing that remains acquire value on the basis of their elusiveness and their scarcity; qualities that derive from their signification as “incomplete, lacking in finality, forgotten or hidden”. [1] As the title of Chow’s essay suggests, however, the digital era has altered the traditional status of remains. The transformation of traces of the past into data privileges “the ease of the save” as all that is required for their preservation. [2] For Chow, this ‘regime change’ may have unexpected ramifications. As she writes, “Yet if everything can be left, nothing really is. Data so saved is perhaps no longer what we would call remains”. [3]

This article is guided by an overarching question: can filmic resurrections of archival footage assume the patina of remains, particularly within the digital economy of ‘the save’ that Chow describes? This question will lead us on to several others. Why should remains continue to be cultivated in the contemporary era? What do they offer us that newfound conceptions of data cannot? And can digital technologies exceed their nearly default affiliation with data to encompass remains? As such, Chow’s observation succeeds as provocation, enabling a meditation upon a burgeoning cultural imaginary that has its basis in the promise of digital preservation as that which will vanquish myriad forms of loss.

John Akomfrah’s essay film, The Nine Muses (2010), will serve as my primary case study in this regard. For the making of this film, Akomfrah received a Made in England bursary, funded by the BBC English Regions Program and Arts Council England. The only stipulations that accompanied the bursary were that recipients use materials from the BBC televisual archive and address a specific region in England (the West Midlands). These stipulations notwithstanding, The Nine Muses exemplifies its director’s longstanding, self-proclaimed obsession with archival materials. Akomfrah characterises this obsession as working with “ghostly traces of lived moments, those pariah images and sounds that now occupy a unique space somewhere between history and myth”. [4] In his film, Akomfrah primarily employs images and sounds from the BBC archive that assume something of an indexical function in relationship to Black and Asian migration to Britain between the years 1947 to 1970. In addition, some of the images that he employs are themselves fictional representations (clips drawn from films that focus on the migratory experience). While Akomfrah’s previous films, installations and writing are similarly riven by the desire to make visible the remaining vestiges of the imperial past, The Nine Muses bears a complex relationship to the archive. The original soundtracks accompanying many of its images were removed as a result of their ‘Voice of God’ quality and their overt racism. [5] By utilising essayistic techniques, Akomfrah re-contextualises these images, transforming their limitations into the grounds for an imaginative aesthetic project that is dedicated to a history without its official modes of remembrance. [6]

All That Is Left Behind

Broadly conceived, Chow identifies remains as among the most productive aspects of leftist political projects. [7] She argues that Marxist modes of thought, in their materialist leanings, often privilege precisely what “has been left behind” as a way of naming socio-economic unevenness. [8] As a result, “social justice is always part of a discourse of remains”. [9] Unlike endless sheaths of data that need never be deleted, Chow defines remains by their scarcity and political potential. Turning to philosopher Jacques Derrida, Chow notes that it is precisely in the present juncture that the status of writing as an act of inscription can be revisited. As she states, Derrida’s notion of arche-writing is marked by a rupture that “breaks open (a ground, a route, a path)”. [10]

Arche-writing is a term that emerges from Derrida’s dismantling of the binary opposition between speech and writing in Of Grammatology (1974) and, more expansively, through his critique of the Western metaphysical tradition. As elucidated by Gayatri Spivak, Derrida’s critique forms “a shorthand for any science of presence”. [11] In Of Grammatology, arche-writing refers to practices of inscription which can include writing in the conventional sense but also “cinematography, choreography and of course, pictorial, musical, sculptural ‘writing’”. [12] Arche-writing also denotes Derrida’s life-long investment in the articulation of ‘trace structures’ that are haunted by an absolute absence. As Derrida explains:

The hinge (brisure) marks the impossibility that a sign, the unity of a signifier and signified, be produced within the plenitude of a present and an absolute presence. That is why there is no full speech, however much one might wish to restore it by means or without benefit of psychoanalysis. [13]

For Derrida, any marker of presence only ever constitutes “a play” between absence and its opposite. [14] As Spivak puts it, “trace-structure, everything always already inhabited by the track of something else that is not itself, questions presence-structure”. [15]

While it is beyond the scope of this article to delve into the specificities and complexities of Derrida’s book, a number of Derrida’s remarks on the nature of arche-writing clarify Chow’s brief evocation of the term when she theorises the “artifactual plenitude” of the data regime. [16] While the ‘ideal’ data regime has yet to come into being in all of its fullness, Chow argues that it too will be predicated upon the fantasy of absolute presence, diminishing the tensions between “retention and escape, between appearance and disappearance” that lie at the heart of all acts of inscription. [17] For Chow, the endlessly renewable nature of the data regime is also resistant to scar formation. As she notes, a second promise of the digital age involves the ability of life forms to regenerate from physical injury without suffering visible scaring. [18]

It is clear that Chow’s conception of ‘data’ is not necessarily synonymous with actual data forms, a manoeuvre that is itself Derridean in its orientation. [19] Faculties of “the human sensorium” and human activities are necessarily about absence and limitation as much as they are about presence and the quest for completeness. [20] For Chow, data stands in for a paradigmatic shift with regard to the act of preservation. What Chow refers to as “human sensuous activity” is gradually being displaced by mechanised tools of data preservation and dissemination – those tools make it easy to not do the work of differentiating between what should be saved and what can be deleted. [21] As such, a digitally based plenitude is underscored by an implicit desire to do away with contingency, unpredictability and chance; all integral components of archival work writ large. Without the imminent threat of loss or failure of discovery that looms over remains, can data retain a similar political force? Chow ends her piece by asking a different though interrelated question: whether or not humans “should be treated as data or, as writing?” [22]

While Chow lists institutions such as museums, temples, churches and older libraries as the traditional abode of remains, the material archive is another site that goes unmentioned but implied by her grouping. Both Michel Foucault and Derrida after him have theorised the official archive as an institution of power and authority that determines how the past is produced, shaped and received by its users. As Foucault writes in “The Historical a priori and the Archive”:

The archive is not that which, despite its immediate escape, safeguards the event of the statement, and preserves, for future memories, its status as an escapee; it is that, which, at the very root of the statement-event and in that which embodies it, defines at the outset the system of its enunciability. [23]

In Archive Fever (1995), Derrida’s much cited statement regarding the archive’s role in structuring the past is as follows:

No, the technical structure of archiving archive also determines the structure of the archivable content even in its very coming into existence and in its relationship to the future. The archivization produces as much as it records the event. [24]

In line with Foucault and Derrida, Achille Mbembe in “The Power of the Archive and its Limits” assigns the archive something of a religious function (akin to a burial ground) where the remains of potentially subversive pasts are contained and rendered dormant. [25] And while Foucault denounces a view of the archive as that which makes possible the resurrection of long-forgotten documents, Mbembe offers an evocative description of just such a process. In Mbembe’s view, materials in an archive can be reintegrated into “the cycle of time” when they are put to use in texts or monuments that provide new spaces of habitation and signification. [26]

The archive has long exceeded its traditional affiliation with a specific place that houses works of art, the digital domain and so on. As such, Mbembe’s statement can be construed as part of a broader shift in the scholarly discourse that surrounds the archive as well as the reception of such materials. Derrida is an instrumental figure in this regard as he claims that the archive is oriented toward the future, involving “the question of response, of a promise and of a responsibility for tomorrow”. [27] In a cinematic context, Jaimie Baron has coined the term “the archive effect” to more precisely account for such a shift. As she writes, “I argue that the contemporary situation calls for a reformulation of ‘the archival document’ as an experience of reception rather than an indication of official sanction or storage location.” [28]

In delving into the BBC archive for The Nine Muses, Akomfrah assumes the task of ‘breaking open’ and further forging a newfound path to signification by severing many archival images from their accompanying sounds. [29] His film provides these images with a new space of habitation. But it is here that we can return to Akomfrah’s designation of archival film as “pariah images and sounds”. [30] To borrow another term from Baron, it is the ‘unruliness’ of signification that underlies Akomfrah’s assertion, thereby calling the indexical status of the archive into question. This idea is further solidified by Akomfrah’s description of archival materials as residing somewhere between “history and myth”. [31] Returning items from an archive back into the public domain, in all of their instability, reintegrates them into the flow of time. And yet, this is the moment when they can also assume the status of remains. In their altered form, these materials are made elusive once more as they allude to their past in its finite and limited guise, while signifying something else for the present and future. Across a wide range of art-based practitioners, digital technologies have become instrumental in returning archival materials into circulation, allowing for a definitive break with the data regime in the production of remains. This is clearly the case with Akomfrah, who had to digitise all of the material from the archives that he utilised, a process he describes as a “massive manual labour”. [32] Akomfrah’s labour is a far cry from “the ease of the save”. [33]

In Cinema and Sentiment (1982), Charles Affron advances an argument regarding the expressive capabilities of the cinema that is entirely applicable to the experience of viewing archival materials within a cinematic context. He argues that cinema’s “figuring of sensation” draws the compositional attributes of the medium towards “a status of presence” or what he refers to later as a “fiction of presence”. [34] As such, the cinema is able to imbue archival images with the status of presence so that we can view the remains of the past within the present tense of the viewing experience. This is one of the ways in which the cinema can restructure our reception of archival materials. In The Nine Muses, however, the image’s fiction of presence is continually disrupted through various means such as voice-over narration, drawing our attention to various instantiations of absence. The essayistic qualities of The Nine Muses are instrumental in transforming its archival base into something akin to Chow’s notion of remains – as that which hovers somewhere between appearance and disappearance.

Intermedial Interventions: Re-contextualising the Archive

In Timothy Corrigan’s succinct definition, the essay film aims to provoke an intellectual response to questions posed by an “unsettled subjectivity”. [35] Corrigan’s definition is readily applicable to The Nine Muses where an unsettled subjectivity emerges during the course of the film, especially in terms of ambivalences regarding the difficulties of migrant settlement. The film’s implicitly rendered conviction is that migrants arriving to Britain were citizens of the nation and did, in a legal sense, belong. As Corrigan and others explain, the essay film aims to preserve the process of thinking through its dialogic tendencies. In addition, essayistic filmmaking has an ability to draw from and “think through” a multiplicity of narrative and non-narrative forms. [36] As such, reflexivity is among the essay film’s most significant attributes. [37]

In The Nine Muses, however, Akomfrah also seeks to depict the process of feeling. In the press materials for the film, he recalls asking his family about their own migrant experiences, a gesture repeated by his longstanding collaborators, Lina Gopaul and David Lawson. They all responded by designating the UK as the coldest place that they had ever lived. As Akomfrah tells the story, the cold was a matter of climate. [38] The film itself suggests that the sensation of ‘coldness’ can be extended to larger questions of hospitality. Akomfrah’s emphasis on bringing the emotional story of these journeys to light is in keeping with the ‘long view’ of his work that returns us to the era of the Black Audio Film Collective. As he notes in an interview with Kodwo Eshun, the questions that animate his work and that of the Black Audio Film Collective are not formal but emotional. [39] The film exemplifies what Ben Highmore delineates as a characteristic feature of Akomfrah’s work. That is, his tendency to “interfere” with archival materials in order to generate a mood or an affective response. [40] More precisely, the intermedial nature of The Nine Muses demonstrates the conditions of possibility that these images yield in making visible journeys of arrival and the early days of settlement while simultaneously drawing attention to the limitations of these images to tell the entire story. That story exceeds the boundaries of the official archive and moves into affective and imaginative terrain. [41]

In his pioneering work, Dick Higgins uses the term ‘intermedia’ to categorise artistic work that “falls between media” and establishes cross-media configurations. [42] The essay film is inherently intermedial in its formation: its lineage returns us to the literary essay and a number of its signature attributes such as the “dialogic tension” between visual and verbal domains and a penchant for various kinds of transgression. [43] As Theodor W. Adorno outlines in his canonical piece “The Essay as Form”, the essay is a literary form that has been condemned precisely for its hybridity. [44] The essay film, as Corrigan puts it, “inhabits other forms and practices” by staging relationships between fiction and documentary, narrative and non-narrative modalities”, relationships that can also be described as intermedial in their orientation. [45]

Given its intermedial method of proceeding and its dialectical nature, the essay film readily evokes the notion of montage and Sergei M. Eisenstein’s conception of intellectual montage, in particular. [46] We can also discern a montage impulse across much writing about the literary essay. For example, Adorno proffers an analogy between the essay as form and a person learning to read in the absence of a dictionary. For Adorno, the reader will learn the meaning of a single word “thirty times in continually changing contexts”; in contrast, he deems a dictionary to be “too narrow in relation to the changes that occur within changing contexts” as well as “too vague” in relationship to the specificity of these contexts. [47] In an essay, meaning arises as a result of how various configurations of concepts assume the form of a “constellation”. [48] In its formal attributes, then, the essay can just as easily be described as a work of montage. As Adorno argues, in fact, discontinuity is “essential to the essay”. [49] Akomfrah’s ample use of a montage aesthetic throughout his body of work is well documented and The Nine Muses is no exception. [50] The designation of The Nine Muses as an essay film, however, enables us to situate its elements of montage within the broader tradition of essayistic practices. In Akomfrah’s film, those practices are put to the service of providing a new space of habitation for the archive, especially in terms of long neglected images and sounds relating to Black and Asian migration and settlement.

The Nine Muses offers distinct and fragmented renderings of its medial components. These components include televisual footage from the archive as well as digital imagery of Alaska and Scotland. The literary text that appears on-screen often expresses fragments of the Western literary and philosophical cannon without matching the text to accompanying images or voice-over narration. The film’s opening sequences can be taken as an archetypal illustration of the essay film form and its constellation-like configuration. Weaving together different medial elements, the film functions like the multiple threads of a carpet, to draw upon the words of Adorno. [51] The Nines Muses begins with a series of slow moving shots across a barren yet magisterial landscape of snow-covered mountains. An austere musical score and a voice that is singing a melancholic tune accompany these images. Near the end of these shots, a second voice is heard cracking through the first, expressing equal parts anguish and rage. The sequence functions as a prologue that generates a sombre mood.

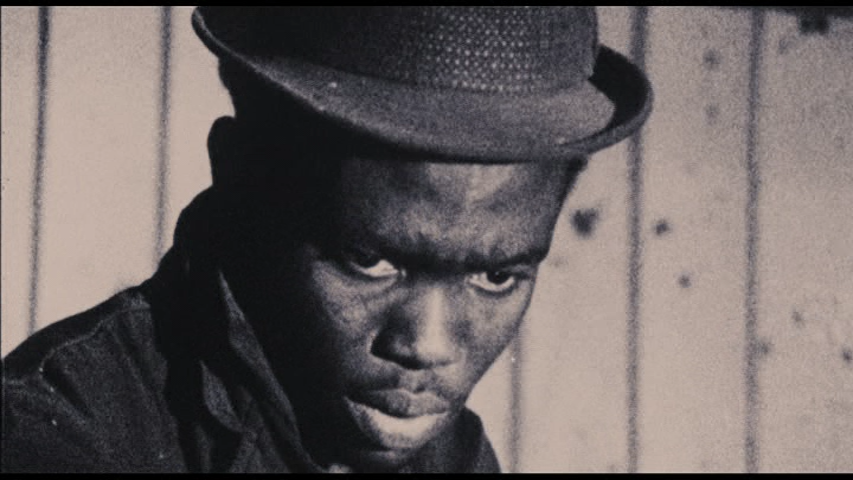

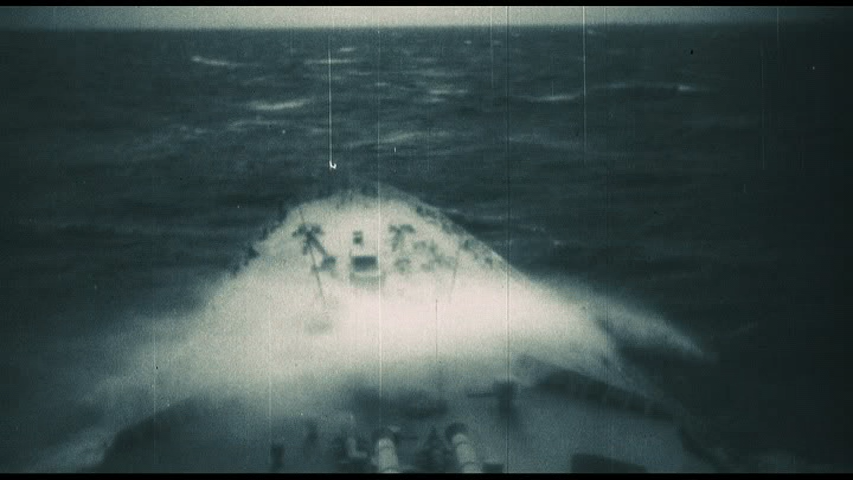

An image featuring text follows: “The gold fell very high in the sky/And so when it hit the earth/it went down very, very deep”. Akomfrah’s use of on-screen text is a clear example of an intermedial reference. As Irina O. Rajewsky defines it, intermedial references consist of medium-specific references to another medium. [52] Through his images of text and his use of voice-over narration, Akomfrah makes film-specific references to his literary sources. Though not cited in the film, the on-screen quotation that appears in the prologue derives from John Berger and Jean Mohr’s A Seventh Man (1975), a book that addresses the plight of migrant workers in Europe. The text is excerpted from a longer exchange that begins with the excitement of a migrant worker who expresses his desire for ‘gold’ upon arrival, only to be met by deflating response that emphasises the arduousness involved in such an endeavour. [53] The sounds that can be heard are recognisably industrial in nature, evoking the soundscape of a factory. Later in the sequence, Akomfrah oscillates between shots of a boat travelling across a river in Alaska and the archival clip of a black man at work in a factory. Although the shots of the boat will eventually feature a hooded figure clad in colourful, contemporary winter gear, Akomfrah’s alternation between the two scenarios gives us the impression that the hooded figure is journeying through the past and moving through the archival remnants of a collective history. The voice-over narration employed during this sequence is one of the few instances of narration in the film that stems from the archive itself. Presumably, the narration originates from the man seen in the archival footage. He states that if “they” (that is, the British) had not come to their country: “We would never have come to theirs. If we had not come, we would be none the wiser. We would still have the good image of England, thinking they are what they are not. And the English would be ignorant of us”.

Alternation between images, sounds and text is how Akomfrah’s film proceeds: “methodically unmethodically”, as Adorno puts it. [54] The film utilises this pattern from beginning to end. Each medial component retains the marks of its own medium-specificity in visual and sonic terms while also being brought into different modes of relationality, resulting in what Chiel Kattenbelt refers to as “mutual affect” between media. [55] In this sequence, the mutual affects that are generated from Akomfrah’s intermedial relations range from the melancholic to a deep-seated ambivalence. If the film establishes an elegiac mood (Akomfrah’s default aesthetic, according to Highmore), this affirms his stated aim in privileging of the often-fraught emotional tenor of migrant journeys. [56] The film begins with an archival extract that indicts the British imperial order for its circulation of an idealised image of the nation that sparked migratory journeys from former colonies. By doing so, the film constitutes a powerful response to past and present anti-immigration rhetoric that sidestep this history, especially in terms of its calls for migrants to return home. The voices that are heard singing during the film’s prologue foreshadow the sentiments of the voice-over narration itself, conveying sensations of sadness, anger and pain through abstract means. The entirety of the sequence recalls Mbembe’s observations concerning the politically subversive nature of archival materials. Once returned to the public sphere, these materials allude to the past as much as they bear relevance to the present, especially as anti-immigration sentiment continues unabated within post-Brexit Britain.

Akomfrah’s use of on-screen text in this sequence points us towards his second aim. That is, he claims to draw heavily upon a predominantly Western canon of literary references to suggest that these texts belong to this particular group of migrants (those who arrived to Britain as new citizens of the nation). [57] As such, Akomfrah stages an act of reclamation that counters the relegation of all migrants to the category of the non-Western ‘Other’. In their “Note to the Reader” at the start of The Seventh Man, Berger and Mohr outline the parameters of their task. They seek to offer pictures and words that do not always correspond to each other, thereby excavating the difficult conditions of European migrants in the post-war period. [58] They explicitly exclude considerations of migration from former colonies to European nations, including Britain. [59] And yet, Berger and Mohr’s reference to the ‘gold that fell high from the sky’ is one that we can attach to the migrant imaginary of an enchanted London, for it makes its way into black migration narratives to Britain in multiple iterations. [60] A central conceit that underscores The Nine Muses is that narratives of black migration to Britain are an integral component of a specifically Western history of migration. As such, they partake of Western tropes and myths. It is telling that Berger and Mohr omit the considerations of migration from former colonies even though they bear similarities to those migrating from southern Europe because “the history of their presence in the metropolitan centres belongs to the history of colonialism and neocolonialism”. [61] Their justification for such an imperative involves providing a “clearer focus” for what they perceive to be a new order of European-based migration. In drawing upon text from Berger and Mohr’s book for the opening of his film, Akomfrah exemplifies the wider applicability of their project, demonstrating an understanding of precisely what they choose to exclude. [62] Certainly, their emphasis on excavating the migrant economy as labour-intensive and exploitative resonates with the kinds of archival images that Akomfrah uses, including images of migrant labour. Such images serve as visual evidence of the very reason why migrants were brought to Britain during the post-war period. [63]

In the opening sequence, the mutual affects between media (text, voice-over and imagery) are demonstrative of the productive nature of ‘habitation’ and the staging of different modes of expression that can occur through a montage aesthetic. While there is an affinity between Berger and Mohr’s approach and Akomfrah’s (all induce productive dissonances between images and text), Akomfrah’s methods are also informed by the essayistic strand of documentary filmmaking. That strand is embodied in the work of directors such as Chris Marker, Chantal Akerman, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard and others, and all are indebted to the montage tradition.

To take another slightly different example, consider the section of the film that begins with the title “Terpsichore: The Muse of Dance”. After this section begins, it is followed by a famous passage from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night: “If music be the food of love, play on” the film’s voice-over recites. Archival extracts featuring individuals belonging to British Asian and Black communities dancing and playing various instruments follow. A classical score accompanies these images although it is at odds with the activities seen in these clips such as when the Indian dancers clap their sticks together as part of dandia rasa. [64] Images featuring the lone body moving through a snow-filled Alaskan landscapes are also interspersed with the archival footage. The “Terpsichore” sequence is exemplary of the overall structure of the film. As its title suggests, the film itself is subdivided on the basis of the ‘Nine Muses’, also narrating the Muses’ birth near its beginning. By resituating migrant journeys within a mythic framework, Akomfrah undermines their affiliation with market-driven demands. In this film, migrant journeys are integrated within a specifically Western imaginary: as epic stories of the West. In concert with the prologue, the “Terpsichore” sequence is also indicative of how the words of a canonical British text can be made to signify in relation to Black and Asian experiences of settlement in Britain. Akomfrah maintains an awkward discordance between the images, the voice-over and the use of music, while also evoking a clear sense of ‘Englishness’. [65] As such, the collision between these textual elements implicitly alludes to the struggles of migrant belonging. As is characteristic of the essay film, a tension between visual and verbal registers is the structuring principle for The Nine Muses. The repeated citation of Western canonical texts signifies within and against the imagery that is being paired with it.

In Twelfth Night, the dialogue that is spoken by Shakespeare’s character of Orsino is melancholic in nature, expounding on the difficulty of love and of being loved. Orsino’s emotional conflict is transposed onto the film’s images, suggesting ideas of welcome and acceptance. Simultaneously, the voice-over narration gestures towards a certain ambivalence that is not readily visible. This ambivalence can be discerned across numerous instances in the film. One particular sequence from a BBC documentary, The Colony (Philip Donnellan, 1964), powerfully reverberates with Orsino’s words. In this clip, a Jamaican man says: “Love, love, love. Cause I love you but majority of you don’t love me”.

To recall Corrigan’s words on the essay film, we might say that the ambivalent tenor of Akomfrah’s film is the mark of an ‘unsettled subjectivity’ in its displaced form. His juxtaposition of multiple medial components exudes both the potentialities and the limitations of the existing archive to convey the story of arrival and settlement. The film’s play between absence and presence also dovetails with Chow’s Derridean-inflected notion of remains. Often, the landscape-based imagery of Alaska that permeates the film features just one or two figures. Such imagery expresses a profound sense of isolation, corresponding to experiences of migrant settlement in ways that cannot be conveyed through recourse to the archive alone. As mentioned previously, some of the Alaskan imagery also involves shots of a hooded figure travelling across the river by boat. During these moments, we either assume the point-of-view of the traveller or we observe hooded figures gazing out from the river. These sequences evoke the sensation of journeying itself. That sense of journeying does not manifest itself in the existing archive (the latter features long shots of boats arriving into British ports). And yet, these sequences are hardly fixed in their meaning. Their abstract quality signals the impossibility of ever completely recovering and depicting how the past might have felt for those living through it. Nonetheless, aspects of a largely oral narrative from the past can take on the status of presence in reconfigured form, much like the scene from Handsworth Songs that I described at the start of this article. [66] As a result, absence is never fully materialised in this film. The Alaska sequence gesticulates towards remembrance and forgetting in the same moment. In conjuring up the past as sensation (primarily through the use of expressionistic and other abstract means), Akomfrah immediately raises the possibility of never being able to remember at all. The journey itself and the subsequent ‘tug-of-war’ between belonging and not belonging and being settled or unsettled becomes part of the emotional textures of this narrative, echoing other essayistic and scholarly accounts of the diaspora within a transnational framework. Historically speaking, the profound disjuncture that was experienced by post-war migrants as British ‘citizens’ and the racialised hostility that they encountered upon their arrival suggested that one could not be both Black and British at the same time. That tension is the historical ground upon which a similar ‘tug-of-war’ has been enacted across generations.

In his famed essay, “Stranger in the Village”, James Baldwin describes the inhabitants of a tiny village in Switzerland where he retreated to write. [67] As he explains:

The most illiterate among them is related, in a way that I am not, to Dante, Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Aeschylus, Da Vinci, Rembrandt and Racine; the cathedral at Chartres says something to them which it cannot say to me, as indeed would New York’s Empire State Building, should anyone here ever see it … go back a few centuries and they are in their full glory but I am in Africa, watching the conquerors arrive. [68]

Baldwin articulates the deep sense of ambivalence and anguish that accompanies the experience of being “strangely grafted” onto the West. [69] However, in a later interview, he makes an assertion that chimes more readily with the vision of the essayist as a ‘borrower’: “I believe what one has to do as a black American is to take white history, or history written by whites and claim it all – including Shakespeare”. [70] I view these statements as emblematic of an observation made by Homi K. Bhabha. Rather than moving from being unsettled to a gradual process of settlement, Bhabha suggests that the diasporic experience perpetually oscillates between belonging or even claiming and dislocation. [71] Similarly, Akomfrah’s reclaiming of texts from the Western canon signifies belonging as much as it does the inability to fully do so. That tension is exhibited in the awkwardness of the distinctions that Akomfrah maintains between text, voice, images and music.

Bhabha further says, “You cannot iron out historical memories of displacement”. [72] The resistance that this particular past and, by that matter, all historical pasts, raise to being unfolded across a linear trajectory finds a charged expression in the formal attributes of The Nine Muses. While his sets of images follow on from each other, their cumulative effect creates the impression of multiple pasts and presents, each commenting upon the other and emerging side-by-side. This characteristic of the film is perhaps what prompted one reviewer to argue that The Nine Muses resembles a moving-image installation piece, rather than a documentary or a work of narrative fiction. [73]

Association/Disassociation: Beyond Indexicality

Akomfrah’s deployment of image, voice and text re-contextualises archival footage so that its potential and its shortcomings are simultaneously on display. In doing so, he foregrounds textual habitation as an aesthetic counterpart to the broader subject of the film: the question of physical habitation. Dislocation and discord are embedded in the very form of the film, mirroring both the physical and emotional aspects of dislocation that were experienced by migrant populations upon first arriving to Britain.

Affective sensations of displacement are also expressed by Akomfrah’s play with the indexical status of his archival footage, extending its signification out beyond its normative categorisation as a historical ‘trace’. Akomfrah’s images are ‘unruly’ in ways that challenge their authoritative status as evidentiary traces of a period of migration – a status that has been conferred upon them, in part, by their archival preservation. In those sections of the film that are comprised of interviews with the Barbadian author George Lamming, he describes the feeling of not being able to call out to hundreds of people around you. For Lamming, this is the initial experience of the West Indian arriving in Britain: “No matter how tough he is, for the first time in his experience, he is alone”. But then he goes on to say that one becomes settled so that “then you too become part of the strangeness”. Recalling Bhabha’s observations concerning the perpetually unsettled nature of the diasporic experience, it is significant that Lamming’s notion of settlement involves becoming part of a strangeness that never recedes. These statements summon up states of loneliness and disorientation that correspond with Akomfrah’s work. That is, Akomfrah utilises documentary archival footage in conjunction with contemporary imagery to conjure up an affective response. By doing so, he diminishes the indexical status of a number of the documentary sequences so that they give way to abstract articulations of the tumultuousness, the arduousness and the disquiet of migrant journeys.

Akomfrah tempers the indexical connotations of the archive through associative forms of editing, juxtaposing the past and the present. [74] Here, editing directs the viewer’s eye towards the differences but also, more importantly, the similarities between the images. Rather than featuring migrant populations as such, Akomfrah returns to landscapes or individuals travelling through adverse conditions. In the first section of the film “Calliope: The Muse of Poetry”, for instance, the imagery of snow storms and snow-filled landscapes appears, once again alternating between archival and contemporary footage. The voice-over narration recites the opening verse of Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost. Archival footage of individuals walking through a storm is graphically matched with the hooded figure seen in the Alaskan snow. In Milton’s verse, he famously describes the biblical origins of the world as stemming from the loss of Eden and extending into a period of ‘chaos’. In The Nine Muses, however, Milton’s verse finds its on-screen connection with imagery of the British Midlands in disarray.

Across the film’s different sections, strong tensions between association and disassociation arise. This is because Akomfrah disrupts a direct relationship between the voice-over and the image. As exemplified by the poem itself, the verse describes a beginning that is marred by loss but inflected by greatness. Similarly, Akomfrah’s images relay a narrative of hardship in an inhospitable climate, borne out through multiple registers. Later in the film, Akomfrah interweaves footage of black migrants on ships with contemporary footage of the hooded figures in Alaska on a boat, also including archival images of a tumultuous sea. During this sequence, the voice-over narration includes passages from Homer’s The Odyssey, narrating the moment when Telemachus sets out on a journey to find Homer. Here, archival images of the stormy seas match the difficult journey that is being narrated. When coupled with images of migrant boats arriving to shore and shots of the sea, the voice-over appears to express both the gravity and the emotional upheaval of these journeys. Shots of the migrants’ arrival, alone, could not fully materialise such sensations. In these sections of the film, Akomfrah reveals how the deficiencies of the archive can be productive, especially in terms of expressing the affective register of the migrant experience. This enables Akomfrah to develop new aesthetic procedures that try to re-imagine what an archive is not always able to preserve (even as he includes the use of archival images). As such, Akomfrah’s ‘archive effect’ is periodically interrupted while also being underscored by contemporary landscape imagery. Graphic matches help to solidify the film’s repeated transitions between archival and contemporary footage, assuming the role of another structuring principle.

There is one section of the film where a reversal of this strategy is discernible, however, where a fictional film sequence appears to signify as documentary. In a section titled “Thalia: The Muse of Comedy”, Akomfrah includes archival footage of Enoch Powell, the absent figure from Handsworth Songs. In this segment of Powell’s notorious ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, Powell describes the feeling of resentment that ferments among the British populace when confronted with migrants in their midst. This footage is buttressed with archival and contemporary shots rain and of floods, visually underscoring Powell’s frequently cited sentiments regarding the violent outbreaks that he predicted would follow after passing of the 1968 ‘Race Relations’ Bill. (This legislation made it illegal to refuse housing, employment or public services on the basis of racial difference). Here, Akomfrah intersperses black and white footage of police officers arresting white individuals with Powell’s speech. Aspects of his speech continue to be heard over the images: “This is why to enact legislation of this kind before parliament at this moment is to risk throwing a match onto gunpowder”. The footage is followed by additional archival images of children burning things in a large bonfire, as well as close-ups of George Lamming’s eyes making it appear as though he were observing these events with dismay.

During a public screening of The Nines Muses, Akomfrah was asked if the footage of the black police officers in this sequence was ‘real’ in the documentary sense. Given the fact that Akomfrah embeds this sequence within a series of archival clips, the query itself seems justifiable. [75] While Akomfrah confirmed the fictional status of the footage; he added that he wanted to cultivate a certain indeterminacy so that the sequence acquired utopian connotations. Here, it is black police officers that prevent white individuals from enacting violence. In accordance with Powell’s inflammatory language, those individuals who are deemed to have lit the ‘match on gunpowder’ in the first place are the ones who extinguish it.

For Akomfrah, archival materials reside somewhere between history and myth. Such a stance is evidenced by his extension of the indexical status and signification of archival imagery. The example described above adds a further dimension to Akomfrah’s archival aesthetic, indicating the pleasures that can arise from viewing such images in new and unexpected contexts. In this regard, The Nine Muses accords with filmmaker Hans Richter’s own emphasis on the essay film. For Richter, the essay film emerges not just from an ‘unsettled subjectivity’ but from a profoundly imaginative one. As he writes, “The essay film, in its attempt to make the invisible world of imagination, thoughts and ideas visible, can draw from an incomparably larger reservoir of expressive means than can the pure documentary film”. [76] If remains are historically tethered to the human sensorium and its attendant activities, as Chow suggests, then Akomfrah’s use of voice-over, contemporary imagery, music and text constitutes a sensuous as well as imaginative act of interference. While continuing the aims of essayistic practitioners who seek to retain the process of thinking in their works, Akomfrah’s evocation of mood, sensation and feeling both augments and alters the signification of archival images.

Absence/Presence Today

And yet, there is one significant departure that The Nine Muses stages from many existing definitions of the essay film. With reference to Handsworth Songs, Allison Wieglus argues that The Nine Muses is not marked by instances of author-centred self-reflection. Often, self-reflection functions as the most explicit indicator of the essay film’s ‘unsettled subjectivity’. [77] Akomfrah and his collaborator Trevor Mathison make a number of appearances in the film. They appear together in the guise of silent hooded figures in Alaska while Mathison appears as himself in the sequences set in Scotland. At times, their presence on-screen signifies as an abstract depiction of the sense of isolation that is felt by migrant populations. At other times, though, they appear to assume the mantle of the ones who remember. In The Nine Muses, then, remembering is situated as a collective activity but not such that individuals are subsumed in the interests of the collective. On the contrary, what the film establishes is a politics of solidarity that transpires between the past and the present. The graphic matches involving the hooded figures across the film can be interpreted as visual evidence of such an overture, opening up their meaning beyond Akomfrah’s suggestion that images of Alaska convey the cold.

This reading returns us to the final line spoken by the narrator in Handsworth Songs: “the living will transform the dead into partners in struggle”. In both films, imagery drawn from earlier periods of migration and settlement is brought into a ‘status of presence’. By doing so, Akomfrah’s films enact a powerful political gesture, especially so in a nation where many of its contemporary inhabitants deny the continued potency of an imperial past.

In The Nine Muses, remains are converted into digital and affective data. Here, remains can be read as an essential component in the politics of collectivity and solidarity, giving credence to Chow’s assertion that remains belong to the domain of social justice. And yet, the fragments of the historical past that appear in the film are also rendered incomplete and elusive. Their indexical qualities are continually disrupted to signal absence. The Nine Muses offers a concrete rendering of what it means to work with remains, leaving formal traces of laborious processes behind in the completed film. To return once more to Chow’s distinction between data and writing, we can now advance the claim that The Nine Muses serves as an illustration of audiovisual ‘data’ as a kind of writing. Given Akomfrah’s tendency to hijack a multiplicity of media forms as well as the essay film’s disregard for linearity and its general proclivity for “heresy”, the essay film is conducive to just such an outcome. [78]

Let us revisit one of the questions posed at the start of this article: that is, the question of why the active cultivation of remains might continue to matter in the present. In stating that he wanted to make a filmic tribute to the neglected history of Black migration to Britain, Akomfrah mobilises archival remains in the interests of settling a debt with the past. For Mbembe and by extension, for Chow, the examining of archives means “to be interested in what life has left behind, to be interested in debt”. [79] If we accept the supposition that remains fall within a ‘debt economy’ (in contrast to the fantasy of the “undeleted (data) and unscarred (life)” that Chow recounts), then we can add that the elusiveness of remains acknowledges the limitations of what can be seen, heard and ultimately known [80] . As Chow explains, this is precisely why remains are able to haunt us. [81]

To briefly expand the scope of this article beyond The Nine Muses, I would close by observing that this is an era that is increasingly over-determined by attempts to exert mastery over time and space. In effect, the world is perceived to be entering into a period of chaos as a result of terrorism, global economic crisis and impending environmental catastrophe. [82] As an economic, social and cultural phenomenon, globalisation is dependent upon controls that can be wielded over circulatory channels in order to ensure maximum efficiency and speed. [83] The continued adoption of digital technologies (as they themselves continue to evolve) has only aided this process. As exemplified by the newly post-Brexit Britain and the post-Trump United States, ‘anti-globalisation’ and calls for further control to be exercised over physical borders seems destined to bring migration to a near standstill. Smart technologies are now being lauded for the ways that they may save the world from the ravages of climate change while also being lambasted for gradually diminishing urban environments through enhanced means of surveillance. [84] All of these examples are largely dependent upon both the fantasy and subsequent critique of data as an inexhaustible resource for information, control and power.

At this present juncture, then, the political force of remains lies in their deficiency and their inability to offer up a vision of completeness. The incompleteness of remains potentially opens up a space for dialogue about the past, allowing the past to remain very much alive through reconfiguration as well as futures that have yet to be foreclosed. In addition, the power of remains resides in the kind of presences that they make possible, especially for the purposes of contestation and resistance. Remains are not just about what cannot be recovered but also about what must continue to be imagined, a duality that is crystallised in The Nine Muses.

NOTES:

[1] Rey Chow, “Remains’ Regime Change”, World Picture, Issue 8 (Summer 2013), http://www.worldpicturejournal.com/WP_8/Chow.html (last accessed: 10 February 2017).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Akomfrah quoted in Icarus, The Nine Muses press kit, http://icarusfilms.com/if-muse (last accessed: 21 January 2018).

[5] Akomfrah made these specific remarks in 2012 while he was a distinguished scholar at Carleton University, Ottawa. For further discussions of Akomfrah’s work with sound and voice see Nina Power, “Counter-Media, Migration and Poetry: Interview with John Akomfrah”, Film Quarterly, Vol. 2 No. 6 (Winter 2011): 59-63; Siobhan McGuirk, “Epitaph to a generation: John Akomfrah Interview”, Red Pepper blog, 9 March 2012

http://www.redpepper.org.uk/epitaph-to-a-generation/ (last accessed: 20 January 2018);

and Dagmar Brunow, “Review of The Nine Muses”, Palimpsest: A Journal of Women, Gender and the Black International, Vol. 4 No. 2 (2015): 218-219.

[6] Akomfrah quoted in Icarus.

[7] Chow, “Remains”.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Gayatri Spivak, “Preface” in Jacques Derrida (trans. Spivak), Of Grammatology: Corrected Edition (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1974), p. xxi.

[12] Derrida, Of Grammatology, p. 9.

[13] Ibid., p. 69.

[14] Ibid., p. 71.

[15] Spivak, “Preface”, p. xix.

[16] Chow, “Remains”. While Chow briefly examines Catherine Malabou’s expanded and essentially updated usage of arche-writing, I employ Derrida’s formulation of the term. This is because the footage from the archive utilised by Akomfrah constitutes an instance of inscription in the way that Derrida describes, prior to digitisation.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] There are numerous film and media examples that exemplify the limitations of data preservation. For instance, Giovanna Fossati claims that analogue film still remains the most reliable means of preserving film on film (especially given the instability of digital carriers and their penchant for obsolescence that cannot be quelled without resources being funnelled into data migration on a regular basis). Unofficial digital archives such as the pirate archives described by Kuhu Tanvir have as precarious an existence as their contents, for these are often at the mercy of being deleted on the whims of users. Employing Hito Steyerl’s term for low-resolution digital images that incur scars from their circulation, Tanvir argues that the pirate archive is the abode of the ‘poor image’. See Giovanna Fossati, From Grain to Pixel: The Archival Life of Film In Transition (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2009); Kuhu Tanvir, “Pirate Histories: Rethinking the Indian Film Archive”, Bioscope 4.2 (2013), pp. 115-136; and Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image”, e-flux 10 (2009), http://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/ (last accessed: 21 January 2018).

[20] Chow, “Remains”.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Michel Foucault (trans. A.M. Sheridan Smith), The Archaeology of Knowledge (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972), p. 129.

[24] Jacques Derrida (trans. Eric Prenowitz), Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995), p. 17.

[25] Achille Mbembe, “The Power of the Archive and its Limits” in C. Hamilton, V. Harris, M. Pickover, G. Reid & R. Saleh (eds), Refiguring the Archive (Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002), p. 22. I first came across reference to this piece in Kass Banning’s insightful article on The Nine Muses, although I employ Membe’s work in a different context. See Kass Banning, “The Nine Muses: Recalibrating Migratory Aesthetics”, Black Camera: The New Series, Vol. 6 No. 2 (2015): 135-146.

[26] Achille Mbembe, “The Power”, p. 25.

[27] Derrida, Archive Fever, p. 36.

[28] Jaimie Baron, The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History (London: Routledge, 2014), p. 7.

[29] As noted by Banning, Akomfrah has drawn both explicitly and implicitly upon Derrida’s work for some time, particularly in terms of his preoccupations with the past as spectre. In her essay on The Nine Muses, Banning argues that Akomfrah’s work with the archive in relationship to ‘ghosting’ predates Derrida. See Banning, “The Nine Muses”, p. 135.

[30] Akomfrah quoted in Icarus.

[31] Baron, The Archive Effect, p. 3.

[32] Nathan Budzinski, “John Akomfrah Interview”, The Wire (February 2012)

https://www.thewire.co.uk/about/artists/john-akomfrah/john-akomfrah_the-nine-muses (last accessed: 21 January 2018).

[33] Chow, “Remains”.

[34] Charles Affron, Cinema and Sentiment (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), p. 7.

[35] Timothy Corrigan, The Essay Film: From Montaigne, After Marker (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 55.

[36] Corrigan, The Essay Film, pp. 33-35. See also Laura Rascaroli, “The Essay Film: Problems, Definitions, Textual Commitments”, Framework: Journal of Cinema and Media Vol. 49 No. 2 (Fall 2008): 24-47; and Nora M. Alter and Timothy Corrigan (eds), Essays on the Essay Film (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017).

[37] Ibid., p. 35.

[38] Akomfrah quoted in Icarus.

[39] Kodwo Eshun, “An Absence of Ruins: John Akomfrah in Conversation with Kodwo Eshun” in Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar (eds), The Ghosts of Songs: The Film Art of the Black Audio Film Collective (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007), p. 133.

[40] Ben Highmore, “Giving a Damn”, New Formations Vol. 82 (Spring 2014): p. 145.

[41] As Akomfrah observes in his interview with Eshun, what constituted “black presence” in the archive was always marked by “massive absences”, including those having to do with the context of some of the images he encountered. See Eshun, “An Absence of Ruins”, p. 132.

[42] Dick Higgins, “Intermedia”, Leonardo Vol. 34 No. 1 (2001): p. 49.

[43] Corrigan, The Essay Film, pp. 20-21. At this juncture, it is also prudent to note that Jihoon Kim offers a very specific definition of the intermedial essay film as that which brokers a dialogic relationship between analogue and digital materials. Given that the essay film itself transposes a literary form into a cinematic one, I have refrained from using the term ‘intermedial essay film’ in this context. See Jihoon Kim, Between Film, Video and the Digital: Hybrid Moving Images in the Post-Media Age (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2016), p. 203.

[44] Theodor Adorno (trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen), “The Essay as Form” in Notes to Literature: Volume 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1958), p. 3. To take one of many examples, Adorno argues that the essay leans towards art in its careful attention to the presentation of its materials. It also partakes of theory in its grappling with concepts while not engaging in their wholesale adoption. See Adorno, “The Essay as Form”, p. 18.

[45] Ibid., p. 51.

[46] Sergei Eisenstein (trans. Jay Leyda), “Methods of Montage” in Jay Leda (ed.), Film Form: Essays in Film Theory (New York: Harvest/HBJ Book, 1949), pp. 82-83.

[47] Adorno, “The Essay as Form”, p. 13.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid., p. 16.

[50] As Akomfrah notes, the “montage premise” of The Nine Muses is inspired by improvisational forms of music that take any note as point of departure. He also describes himself as “a born bricoleur”. See Akomfrah in Budzinski, “John Akomfrah Interview”.

[51] Adorno, “The Essay as Form”, p. 13.

[52] Irina O. Rajewsky, “Intermediality, Intertextuality, and Remediation: A Literary Perspective on Intermediality”, Intermediality Vol. 6 (2005): p. 52.

[53] John Berger and Jean Mohr, The Seventh Man: The Story of a Migrant Worker in Europe (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd., 1975), p. 68.

[54] Adorno, “The Essay as Form”, p. 13.

[55] Chiel Kattenbelt, “Intermediality in Theatre and Performance: Definitions, Perceptions and Medial Relationships”, Culture, Language and Representation Vol. 6 (2008): p. 25.

[56] Highmore, “Giving a Damn”, p. 145.

[57] This is a statement that Akomfrah made in 2012 during his time as distinguished scholar at Carleton University, Ottawa. He alludes to a similar reading in an interview with Ben Sachs, where he says that his indoctrination into ‘Britishness’ was through these canonical texts, giving him the right to use these ‘primary materials’ as he saw fit. Finally, Highmore similarly concludes that Akomfrah’s methods allow “migrant images to occupy Western canons”. See Ben Sachs, “The Latest Obsession: An Interview Nine Muses director John Akomfrah”, The Chicago Reader, 3 November 2012

https://www.chicagoreader.com/Bleader/archives/2012/11/13/the-latest-obsession-an-interview-with-nine-muses-director-john-akomfrah (last accessed: 21 January 2018). See also Ben Highmore, Cultural Feelings: Mood, Meditation and Cultural Politics (London: Routledge, 2017), p. 114.

[58] Berger and Mohr, The Seventh Man, p. 7.

[59] Ibid., p. 8.

[60] A key example is Anthony Simmons’ fictional film Black Joy (1975), where a character from Guyana arrives to London and is eventually put on the path of settlement. Searching for his father’s residence in Brixton, he comes upon a series of urban wastelands and houses in various states of demolition. The lyrics of the music utilised during this sequence are as follows: “Have you been told/The streets of London are paved with gold”. See Malini Guha, “Have you been told, the streets of London are paved with gold: Rethinking the Motif of the Cinematic Street Within a Post-Imperial Context”, Journal of British Cinema and Television Vol. 6 No. 2 (August 2009): 178-189.

[61] Berger and Mohr, The Seventh Man, p. 8.

[62] Ibid. There is an immense body of literature within cultural and historical studies that has explored the way in which the presence of migrants from former colonies in Britain troubles the view that colonialism was an external experience. This mode of a nationalised repressed accounts for the failure to recognise that Black and Asian migrants arriving to Britain during the late 1940s and early 1950s were citizens of the nation and a broader failure to address the difficult legacies of the imperial past that reverberate long after the official ‘end of empire’. For examples, see Ian Baucom, Out of Place: Englishness, Empire and the Locations of Identity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989); Paul Gilroy, There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation (London: Unwin Hyman, 1987); Paul Gilroy, After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture (London: Routledge Press, 2004); Stuart Hall, “When Was the Postcolonial? Thinking at the Limit” in The Postcolonial Question: Common Skies, Divided Horizons (London: Routledge 1996), pp. 242-260; and Bill Schwarz, The White Man’s World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[63] For example, see Nina Power, “Counter-Media, Migration and Poetry: Interview with John Akomfrah”, Film Quarterly Vol. 2 No. 6 (Winter 2011): 59-63.

[64] Dandia means ‘sticks’ while rasa means ‘dance’. Dandia rasa is a folk dance from the province of Gujarat, India, where performers clap sticks together while they dance.

[65] In “Locating English Identity”, Ian Baucom argues that the notion of ‘Englishness’ has shifted over the last 150 years. If Englishness was synonymous with ‘Britishness’ and, more specifically, Britain’s identity as imperial nation, then ‘Englishness’ after the decline of empire ceases to be a matter of space and one of racial distinctiveness. The shift from space to race underscores Enoch Powell’s declarations concerning the inability of non-white immigrants and their children to ever become ‘English’. See Ian Baucom, Out of Place: Englishness, Empire and the Locations of Identity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), pp. 3-41.

[66] For a sustained and insightful comparison between Handsworth Songs and The Nine Muses and an analysis of the Alaska scenes as tableaux, see Banning, “Recalibrating Migratory Aesthetics”.

[67] James Baldwin, “Stranger in the Village” in Notes of a Native Son (Boston: Beacon Press, 1955), p. 169. Note that scholars such as Banning have referenced different aspects of this essay when discussing Akomfrah’s tendency for moving back and forth in time.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Jordan Elgrably, “James Baldwin: The Art of Fiction”, The Paris Review Vol. 91 (Spring 1984), https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2994/james-baldwin-the-art-of-fiction-no-78-james-baldwin (last accessed: 21 January 2018)

[71] Homi K. Bhabha, “Mapping a Pluralist Space in Ismaili Studies”. Keynote, 2nd International Ismaili Studies Conference, Ottawa, March 9th 2017.

[72] Ibid.

[73] The Nine Muses began as a single screen gallery installation titled Mnemosyne. This reviewer may have had multi-screen installations in mind when making this comment. See Wendy Okoi-Obuli, “Review- John Akomfrah ‘The Nine Muses’ is a Deeply Moving Experience”, Indiewire, 2 April 2013

http://www.indiewire.com/2013/04/review-john-akomfrahs-the-nine-muses-is-a-deeply-moving-experience-136783/ (last accessed: 21 January 2018)

[74] While Banning also discusses Akomfrah’s use of associative editing, my particular emphasis is on the relationship between intermediality and associative editing.

[75] Akomfrah was asked this question at Carleton University.

[76] Hans Richter, “The Film Essay: A New Type of Documentary” in Essays on the Essay Film, p. 91.

[77] Allison Wieglus, “The Black Audio Film Collective’s Fragmented Cities” in Mediapolis: A Journal of Cities and Culture no. 2 roundtable, Vol. 2 (3 June 2017),

http://www.mediapolisjournal.com/2017/06/black-audio-film-collectives-fragmented-cities/ (last accessed: 21 January 2018)

[78] Adorno, “The Essay as Form”, p. 23.

[79] Mbembe, “The Power of the Archive”, p. 25.

[80] Chow, “Remains”.

[81] Ibid.

[82] This is an observation that is being explored by numerous film studies scholars in varying contexts. For one example, see Erika Balsom, “The Reality-Based Community”, e-flux 83 (June 2017), http://www.e-flux.com/journal/83/142332/the-reality-based-community (last accessed: 21 January 2018)

[83] On this subject see David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change (Oxford and Malden: Blackwell, 1990); Manuel Castells, “Space of Flows, Space of Places: Materials for a Theory of Urbanism in the Information Age” in Stephen Graham (ed.), The Cybercities Reader (London: Routledge 2002); and Saskia Sassen, “Spatialities and Temporalities of the Global: Elements for a Theorization”, Public Culture Vol. 12, No. 1 (Winter 2000): 215-232.

[84] For dystopian views on the global ‘smart turn’, see Orit Halpern, Jesse LeCavalier, Nerea Calvillo and Wolfgang Pietsch, “Test-bed Urbanism”, Public Culture Vol. 25 No. 2 (2013): 272-306 and Rem Koolhaus, “Rem Koolhaus asks: Are Smart Cities Condemned to be Stupid?” ArchDaily, 10 December 2014 https://www.archdaily.com/576480/rem-koolhaas-asks-are-smart-cities-condemned-to-be-stupid (last accessed: 21 January 2018)

[85] Chow, “Remains”.