“Clay…the least commercial work ever made in the history of cinema.”[1]

Almost two decades ago Graeme Cutts quite rightly characterised Giorgio Mangiamele as “one of the forgotten directors of the Australian cinema” (Cinema Papers, 1992, p. 17). In the intervening years, Mangiamele has frequently scored a mention in the new standard histories that have appeared, and has now achieved his own entry in the Oxford Companion to Australian Film. In spite of such formal acknowledgement, however, his actual work has remained largely unexplored. It’s true that in more recent times Raffaele Lampugnani and Gaetano Rando have written illuminatingly about several of Mangiamele’s migrant films, and his only foray into screen comedy, Ninety Nine Per Cent (1963), has also recently received closer analysis.[2] However, either because it never achieved a wide theatrical release or in part simply due to general neglect, what is surely Mangiamele’s most accomplished film, Clay (1965), has continued to be frequently cited but has never received the critical attention that it undoubtedly deserves. The recent restoration of the film by the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) and its release on DVD by Ronin Films provides a golden opportunity for a closer look at what must be one of the most remarkable but also most neglected early films of the Australian revival, indeed only the third Australian feature ever invited to screen in competition at Cannes.[3]

Fashioning Clay

As filmmaker Nigel Buesst amply documents in his Carlton + Godard = Cinema (2003), a widespread cinephilia and more general cultural ferment in the inner Melbourne suburb of Carlton played a significant role in attempts to relaunch Australian feature filmmaking in the early 1960s. Mangiamele, himself a resident of Carlton, was certainly part of what Bruce Hodgson has called the Carlton “ripple” in the revival of Australian cinema during this period.[4] Yet, as Buesst’s documentary also makes clear, Mangiamele operated largely apart from the more university-oriented and French New Wave obsessed movement, and not only because he was a recent immigrant to Australia (naturalised in 1957), with his early films, Il Contratto (1953) and The Spag (1962), focused so squarely on specifically migrant issues.

Just how much, and what sort of, experience in filmmaking Mangiamele brought with him from his period in the photography and film unit of the Italian police force when he migrated to Australia in 1952 remains, despite some concerted research, a matter of conjecture. What is clear, however, is that Mangiamele’s cultural and artistic formation in art schools in Italy—institutions which until the early 1960s remained stubbornly permeated by the idealistic aesthetics of Benedetto Croce—brought him to filmmaking with a very different approach to even that of an other aspiring “art” director such as Tim Burstall, with whom Mangiamele briefly collaborated during this period. It’s Clay, I would suggest, that really embodies this different—and Mangiamele’s very characteristic—approach to cinema.[5] Indeed, as soon as one begins to look more closely it becomes clear that, leaving to one side the migrant and social themes which he had treated in the earlier films, Mangiamele was here attempting quite self-consciously to create something analogous to that “cinema of poetry” that Pasolini was theorising (and practising) in this very same period.

The Italian treatment of Clay, a 19-page typescript conserved at the NFSA, strongly suggests that the film was conceived, rather remarkably, in one fell swoop.[6] The final version of the film certainly does show a number of significant changes and additions—Margot’s voice-over about the possibility of it all being a dream is completely absent from the original treatment, as is the scene in which the well-off couple come to buy some pottery and the one in which the priest comes to scrounge some chickens—but in many ways the film appears to be “all there” in these 19 pages. Interestingly, when asked, many of the actors who worked on the film have declared to have never seen a complete screenplay and yet even such insert shots as that of a car wheel splashing through a puddle can be found, clearly delineated and visualised, in the Italian script, suggesting that much of what’s most distinctive about the film was already there as part of its original conception.[7]

Since the script is undated one wonders when and how it came into being. According to newspaper reports of comments made by Mangiamele himself on set, the original idea for the film had been sparked by a chance visit to the former artist colony of Montsalvat at Eltham, Victoria.[8] One can only presume this to have been after the completion of Ninety Nine Per Cent, and therefore sometime in 1963. By the end of that year Mangiamele must have already completed the Italian version and possibly had it translated into English since by early 1964 he had begun to assemble and rehearse the willing cast in Melbourne and by May was actually shooting the film at Montsalvat.[9] After seven gruelling weeks of filming in very trying wintry conditions, Mangiamele, assisted by actor, Chris Tsalikis, edited the film in his photographic studio at Rathdowne Street, although Tsalikis remembers that post-production of the sound (both Tsalikis and Janina Lebedew were dubbed by Robert Clarke and Sheila Florance respectively) required a further week of work in facilities in Sydney.[10]

Exhibiting Clay

Pre-announced by largely complimentary previews—in The Age by film critic and vocal advocate for a local film industry, Colin Bennett, and in the Herald by David Bornstein—Clay was given its premiere before an invited audience at the Palais Theatre in St. Kilda on 13 December 1964.[11] By all reports the film was received warmly enough by the invited guests although Chris Tsalikis recalls that many attendees also appeared rather puzzled by what they took to be an “arty” film.[12] Ironically, given Mangiamele’s self-professed atheism and hostility to the Catholic religion, one of the most enthusiastic responses to the film came from the reviewer for the Catholic weekly, The Advocate, who characterised it as an “arresting” film and advised its readership to “See this film Clay if you have the opportunity.”[13]

Mangiamele was certainly keen to get the film to an overseas festival but, given that the Commonwealth Government showed absolutely no interest in supporting the film, it remains unclear how it received its invitation to Cannes.[14] Nevertheless, by the end of March 1965, the film had been officially accepted for screening in competition at the French festival.[15] Having mortgaged his house to finance the film, Mangiamele had difficulty in finding the money to follow it to France but the Sitmar Line eventually provided a discounted sea fare for himself, assistant director, Ettore Siracusa and actor and assistant editor, Chris Tsalikis. The extraordinary, and continuing, lack of interest by the Commonwealth government, which failed to even advise its ambassador in France about the fact that an Australian film was competing at the prestigious festival, came to be matched by the ingenuity of Mangiamele who exploited the opportunity of the ship’s docking at Naples on the way to Cannes to invite Italian journalists to an on-board screening of the film. This succeeded in creating a certain amount of ongoing interest in the Italian papers for this “expatriate” Italian filmmaker and the film he was taking to Cannes.[16]

The film screened in the afternoon of 25 May. In the 1992 interview Mangiamele told Cutts that the film’s reception at Cannes was “very, very good” (Cinema Papers, p. 20). Lead actor, George Dixon, who flew there independently for the occasion, remembers a more mixed reaction.[17] Certainly most reviews praised the film’s visual poetry although many also voiced some reservations about the narrative and dialogue. Perhaps none more so than Variety which had reviewed the film at its Australian premiere in December of the previous year and had concluded that, “Photographer Mangiamele emerges streets ahead of scripter Mangiamele or director Mangiamele”. Though it conceded that, “Visually it’s frequently a poem brought to life with some breathtakingly poignant and arty shots”.[18] In its review of the film at Cannes, Variety now suggested that “[the] Pic is technically good and has some okay conception” but “is somewhat too grandiloquent for much chance abroad except for a few arty spots”.[19]

A month later, with Mangiamele still in France exploring the possibilities for European distribution, the film, which in the meantime had won several awards in the Australian Film Award Competition, was included in both the Melbourne and the Sydney Film Festival programs.[20] Curiously enough, in spite of Colin Bennett’s strong praise for the film six months earlier, neither Bennett himself, nor Erwin Rado, director of the Melbourne festival, did anything to promote what was, after all, the only Australian-made feature among the 139 films being screened. This might seem all the more curious given the widely-reported call for government support for the local film industry with which renowned architect, Robin Boyd, opened the festival on 4 June.[21] In the event, the Melbourne festival audience reacted rather tepidly to the film, while the Sydney audience proved to be decidedly hostile.[22] By the time Mangiamele returned to Melbourne in late July, the film had already dropped out of sight in Australia although it was screened in late September of that year in both London and Glasgow as part of the Commonwealth Arts Festival. In August of the following year, undoubtedly hoping to give the film one more airing, Mangiamele personally organised a short season of screenings of both Clay and Ninety Nine Per Cent at the St. Kilda Palais (27–31 August). Competing for attention with foreign big-budget blockbusters such as Doctor Zhivago, Mary Poppins and My Fair Lady, it appears to have done poorly in box-office terms but did attract at least one positive review from Leonard Glickfeld in the Australian Jewish News which highlighted the “pure cinematic poetry” of the film and concluded that Mangiamele “has the potential to be Australia’s first Fellini.”[23] The film received another showing when the ABC, which had bought the television broadcasting rights in March 1965, screened a drastically-shortened 50 minute version as their Thursday movie on the evening of 10 November 1966. Mangiamele was interviewed for the occasion and was reported in that week’s TV Week as characterising Clay as “an experiment, not a money-making deal” in which “the camerawork expresses poetry in a visual form”.[24]

The Film Festival report in the Federation News resorted to metaphor in its characterisation of Clay: “In agricultural terms, Clay is heavy and requires careful handling.”[25] In continuing the metaphor one might say that Clay was effectively buried for the next three decades. In 1998 SBS bought the television rights for a 54 minute version which came to be screened in an afternoon slot on 13 November 1999. The film only surfaced theatrically again in 2003 when an incomplete version of it was shown as part of a Mangiamele retrospective at ACMI.[26]

The Art of Clay

In a very thoughtful account of a long interview with Mangiamele published just after the filmmaker’s death in 2001, Quentin Turnour remarked on the difficulty of teasing formative influences from Giorgio. The neorealists, De Sica and Rossellini? Yes, but only acknowledged after prompting. Warmer and more spontaneous, Turnour recalls, was Mangiamele’s response to the suggestion of a possible influence of the so-called French Impressionists of the 1920s, filmmakers such as Jean Epstein, Germaine Dulac and the early Jean Renoir, with the ensuing discussion demonstrating what Turnour judged as “a now rare knowledge of their work and [of the] the importance of the image and the use of silence in cinema.”[27] Following this lead, Turnour later on in the piece advises a downplaying of that neorealist heritage with which Mangiamele has come to be so predictably associated in favour of a recognition that, in fact, “Mangiamele shares with the ‘high’ silent era an interest in allegorical narrative, the Symbolist image and the filmed dream.”[28] Turnour’s characterisation is, I believe, both perceptive and compelling, and provides something of a key to appreciating the cinematic poetry and the artistry of Clay.

Clay begins with what is surely one of the most stunning and lyrical opening sequences in any Australian film. Amid the high-pitched sound of a whistling wind, the camera floats aimlessly as a leaf between the stark bare branches of gum trees thrust towards the sky like the plaintive fingers of so many upturned hands. A disembodied voice, which we will later recognise as belonging to Margot, begins: “Everything seems so unreal now. Perhaps it’s a dream. Perhaps … what?” [29] As the title appears, unseen kookaburras begin to cackle and the whistling wind is joined by the doleful notes of a muted trumpet sounding alone in the wilderness. The simply-styled credits appear, the camera continues to float erratically through an almost-abstract high-contrast black-and-white treescape, and the wind and the trumpet continue their mournful duet. As we’re drawn, almost hypnotically, in to the image we realise, with a startle perhaps, that the extreme high contrast of the black and white derives from the direct use of the negative rather than the printed positive of the film (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1

Clay: Opening image

(Courtesy: Rosemary Mangiamele)

The boldness of such a move is typical of the daring that Mangiamele displays throughout his film, a film made, we will remember, on a no-shoestring budget. Making a virtue of necessity, one might think, by “the poorest (financially) film director in the world”, as N.A. Kovach called him in a report from the Sydney Film Festival.[30] And yet if one were willing to dig deeper one might find an artistic precedent for such a stratagem in a number of silent films, most notably perhaps, in Jean Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet (1930). In a sequence towards the end of Cocteau’s film when the black angel lies over the body of the dead boy in order to take up his spirit, the transformation is imaged by several seconds of the film switching to negative (Figure 2). [31] Now it is true that Cocteau is not a filmmaker that Mangiamele ever explicitly acknowledged and it would seem almost impossible to establish any direct influence. And yet as soon as one begins to look closely at Clay in this light it becomes almost impossible not to notice the insistent presence of what one might call Cocteau-ean stylemes in what is, significantly, an allegorical—indeed a dream—narrative.

|

Figure 2

Angel covering boy’s body in

Jean Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet (1930)

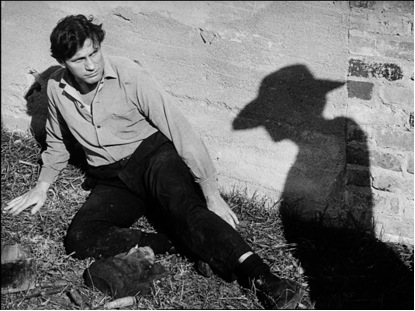

Nick’s dramatic eruption into the landscape, and into the narrative, is done in what at first appears to be a highly-stylised and choreographed naturalism: he is clearly a criminal on the run, desperately flailing his way through a waterlogged countryside with a dozen anonymous policemen in close pursuit. Exhausted and mud-spattered, he collapses onto the wet earth, where he will soon be discovered by Margot and her father as they are driving in the torrential rain to their home at Potters’ Point. But if Nick’s connection with mud and clay is at first accidental and external—he has simply been spattered with it as he has fled from the police—it is soon transformed into a figural identification. Sitting inside the car between Margot and the father, Nick is presented as a clay bust, his face completely covered in mud (Figure 3). Indeed, much more completely muddied than when we last saw his face (Figure 4) in an image strongly reminiscent of Vittorio/Accattone in Pasolini’s Accattone (1961) (Figure 5).

|

Figure 3

From Clay: “He’s like one of your clay models.”

(Courtesy: Rosemary Mangiamele)

|

Figure 4: Clay

(Courtesy: Rosemary Mangiamele)

Figure 5

Vittorio (Accattone) in

P.P. Pasolini’s Accattone

Significantly, to Margot’s question “Who is he?” the father answers: “He looks like one of your clay models”.[32] At this point (but only after running her fingers over Nick’s profile as though he were a clay model), Margot wipes the mud from Nick’s face with a cloth to uncover the human skin beneath. The identification is soon strongly reiterated, however, when Nick, after having had his feet washed and rested, awakens to see that Margot has indeed sculpted a clay model of him (Figures 6-8).

Figure 6: Clay

(Courtesy: Rosemary Mangiamele)

Figure 7: Clay

(Courtesy: Rosemary Mangiamele)

|

|

|

|

Figure 8 – 10: Clay |

||

It is difficult, especially given the other clay statues which we have seen earlier looking down from the shelves of the workshop, not to be reminded not only of the appearance of the statue in Blood of a Poet but also of the ubiquity of animated and non-animated statues in Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast (1946) (Figures 11 and 12).

|

|

|

Figure 11-12: |

|

In his TV Week interview with Annamaria Ardossi, just before that drastically-shortened version of Clay was screened on the ABC in 1966, Mangiamele downplayed any symbolism in the film. “The word ‘clay’, he said, “was chosen for its visual character, not for its symbolism. There is a lot of mud and rain in the film.”[33] But whether Mangiamele was being playfully disingenuous or simply trying to avoid scaring away ordinary television viewers, the film itself amply demonstrates not only its symbolic but, at least in places, its Symbolist poetics. While hardly in the way of an imitation or even homage, the film appears, at least at one level, to be constructing a complex allegory of art and of the artistic struggle very much in the style of Cocteau. We should note that the film is set and shot, of course, at the former artist’s colony of Montsalvat. Significantly, a range of the arts (with perhaps the odd exception of verbal poetry) seem to be purposely included in the film: the father is a potter but also an accomplished painter, Margot is a potter who also sculpts. Nick, who now also exists as one of Margot’s clay statues, is shown in one sequence to be himself sculpting a head in wood. Earlier, outside the dance hall, when quizzed by Margot, he has confessed a passionate desire to return to painting in order to express the beauty of the natural world to which he had only recently awakened. In the climactic fight between Nick and Chris, his rival for Margot’s affection, Chris rather appropriately throws a heavy clay bust at Nick which Nick narrowly manages to avoid. Most Cocteau-like of all, perhaps, a defeated Chris stumbles up from the mud beside a broken statue that perfectly mirrors his broken spirit (Figure 13).

|

Figure 13

Clay: Chris defeated

(Courtesy: Rosemary Mangiamele)

Given Mangiamele’s reticence to acknowledge cinematic influences, such allusions can’t but remain tantalisingly conjectural.[35] If even minimally tenable, however, they would confirm a style of cinema inspired more by the great cinematic experimenters of the silent period than by the modernists who were achieving dominance at the time the film was made. One wonders: was it this orientation that, at least in part, made the film so distasteful to viewers at the Sydney festival?And yet one would want to note that the allegorical dimension of the film is far from being single-tracked. Or rather, within what appears to be its over-arching Symbolist allegory, the film seems able to bring together into a relatively-seamless unity a whole series of disparate poetic and cinematic allusions. The film’s success in kneading these together to the point of expressing them as its own makes their individual identification at times quite difficult. So, for example, one is left to wonder whether Mangiamele’s “rare knowledge” of the French Impressionists conserved a memory of Jean Epstein’s whimsical The Three-Sided Mirror (1927), a film that includes, even if in quite a comic tenor, an episode featuring a male flâneur who frequents a female sculptress who has created a bust of him. Significantly, Epstein’s enigmatic film ends with a speeding car careering out of control, killing the male protagonist who thus reverts to what he had always in a sense been, an insubstantial image in a three-sided mirror. Mangiamele’s love for leaves swirling in the wind, everywhere apparent in Clay, as in previous films, might have originally been triggered by one of the final images of Epstein’s film (Figure 16) where the car’s passage lifts a whirlwind of leaves into the air just before failing to make the curve and slamming into a tree.[34]

|

|

|

|

Figures 14-16 |

||

And yet there was at least one modernist director whose spell Mangiamele could not evade, even in Clay. The proof is in the brief episode featuring the young priest who seems to come to the colony in order to collect some form of tithe. Now, Mangiamele’s atheism and his consequent hostility to the clergy are well known and amply documented. In a late interview with Raffaele Lampugnani, Mangiamele explained the priest’s appearance in the film as an image of how the clergy exploit the populace and literally “scrounge” from them.[36] If so, the implied allusion might be thought to point in the direction of Germaine Dulac’s fiercely anti-clerical The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928). It’s significant, however, that this is one of the few scenes in the film which is absent from the original Italian treatment so that, clearly, Mangiamele must have thought of adding it, in all probability, during filming.

Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963) opened at The Lido in Sydney in February 1964. After doing what the trade journal, Film Weekly, called “record business”, it moved to Melbourne.[37] It was also screened—albeit only once—at the Melbourne Film Festival on May 30 that year.[38]

Given Mangiamele’s declared love of Fellini, there can be little doubt that he must have made the effort to see 8 ½ in one venue or another, and in the very period when he was already rehearsing, if not actually filming, Clay. No doubt delighted at the comic portrayal of the clergy, especially in the Saraghina sequence where the priests chase Guido along the beach in order to castigate him, Mangiamele seems to have appropriated and slightly changed the image to a gawky young priest on a bicycle chasing his hat. In spite of what Mangiamele said about his inclusion of the priest to Lampugnani, the comic touches and the upbeat music in the sequence are distinctly Felliniesque and are clearly reminiscent of 8 ½ (Figures 17 and 18).

|

Figure 17:

Federico Fellini: 8 ½ (1963)

Figure 18:

Clay: the priest

(Courtesy Rosemary Mangiamele)

Pace Mangiamele, to note such a layering in the imagery of the sequence is, of course, in no way to impugn its artistic originality but rather to begin to glimpse the textual density of the film and the depth that lies beneath—or within—what has always been blithely indicated as the beauty of its photography.But, in any case, something more complex is happening here than mere appropriation. Or rather what Mangiamele is appropriating is not just the Felliniesque image of the priest but rather the entire self-reflexive dimension of Fellini’s most autobiographical work to that date. For if Guido chased by priests in 8 ½ stands in for a young Fellini, Nick menaced by the shadow of the priest and rejecting his offer of spiritual comfort (and adapting a version of Diogenes’ famous reply to Alexander for his purpose) stands in for Mangiamele himself (Figures 19-20).

|

|

|

Figures 19-20: Clay |

|

And a further confirmation that the allusion here is indeed to 8 ½ is provided by the way in which the priest’s departure is matched with Margot’s animated entrance, her graceful run onto the scene echoing the charming dance-like entrance of Claudia Cardinale in Fellini’s film (Figures 21-22). But clearly there’s even more here. Given the gradient of the hill, so strongly emphasised by the low camera angle, the other memory that is evoked here is that of the armed priest on the bicycle going off with the husband in Visconti’s Ossessione (1943) (Figure 23).

|

Figure 21: Clay

Margot’s entrance as the priest departs

Courtesy Rosemary Mangiamele

Figure 22: 8 ½

Claudia’s entrance

Figure 23: Luchino Visconti, Ossessione (1943)

Gino watches Bragana and the priest leave

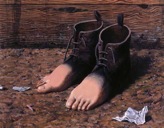

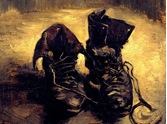

It’s a depth and density of imagery that emerges, for example, from a closer consideration of an earlier sequence of the film when an exhausted Nick is first brought into the potter’s workshop. Margot asks his name in order to introduce him to the group. Having been introduced and having acknowledged the others, Nick looks down with an air of helplessness. The camera pans slowly down his muddied trousers and arrives at his feet, closing in on the sight of gaping shoes with feet showing through (Figure 24). Despite the superficial realism, here, this is an intensely poetic representation of the travails of the traveller, and of the miles he’s trudged through the harsh countryside. Moreover it’s surely impossible for these “shoe-feet” not to evoke at least one of René Magritte’s series of hybrid representations known as The Red Model (Figure 25). Furthermore, given the universal wretchedness and human suffering strongly connoted by the image, what comes to be invoked in the same gesture is probably nothing less than a memory of Vincent Van Gogh’s Boots and Laces (Figure 26).[39]

|

Figure 24:

Clay: Nick’s shoes

(Courtesy Rosemary Mangiamele)

|

|

|

Figure 25: |

Figure 26: |

Nick’s near faint at this point leads to his being seated on a stool while the two women (one of whom is called Mary) now proceed to wash his feet. In spite of Mangiamele’s aversion to Catholicism it’s difficult for such a gesture to avoid some Christological implications (significantly, even in the original Italian script the feet are referred to as “piedi piagati”[wounded feet]). One might think that it’s precisely in order to neutralise these inevitable Christological connotations that the camera, in the sequence immediately following, is made to pan horizontally alongside Nick’s sleeping body rather than looking up from the feet, studiously avoiding any representation that might bring to mind an iconic pietistic image like Mantegna’s Dead Christ (c.1490) (Figures 27-28). As the camera closes in on Nick’s face he awakens to find that Margot is fashioning a clay bust of him.

|

Figure 27 :

Clay: Nick sleeping

(Courtesy Rosemary Mangiamele)

|

Figure 28:

Mantegna, Lamentation Over the Dead Christ (c.1480)

Once again, then, what emerges from such a close examination is the remarkable imagistic and allusive density of Mangiamele’s film, a poetic depth and richness that is either overlooked or misconstrued by a gaze attentive only to its presumed realism and its putative “beautiful photography”.

It’s impossible to go much further in a close analysis of the film’s poetic stratagems within the limits of a journal article. Nevertheless, perhaps even the brief and fragmentary observations offered above may help to suggest the tenor and complexity of Mangiamele’s cinematic artistry in the film and the way in which his aspirations to a poetic cinema come to be successfully realised in Clay. And as tentative as such observations may themselves need to remain, they should nevertheless serve to offer strong confirmation to Tom O’Regan’s unnecessarily hesitant suggestion that art cinema in Australia begins “perhaps” with Clay.[40]

[1] Carlo Laurenzi in Il corriere della sera, 25 May, 1965 (here and elsewhere, unless otherwise indicated, my translation).

[2] Raffaele Lampugnani, “Depicting the Italo-Australian migrant experience Down Under: Images of estrangement in the cinema of Giorgio Mangiamele” in Rita Wilson and Susanna Scarparo (eds.), Studi d’Italianistica nell’Africa australe / Italian Studies in Southern Africa, vol. 18, no. 1 (2005) and “Comedy and Humour, Stereotypes of the Italian Migrant in Mangiamele’s Ninety Nine Per Cent”, Fulgor, vol. 3, no. 1 (December 2006) [ online at http://ehlt.flinders.edu.au/deptlang/fulgor/volume3i1/papers/Lampugnani_v3i1.pdf]; Gaetano Rando, “The Representation of the Italian Australian Diaspora in the films of Giorgio Mangiamele with particular reference to the two versions of The Spag”, in La diaspora italiana dopo la Seconda Guerra Mondiale / The Italian Diaspora after the Second World War (Bivongi, Italy: AM International, 2007) and “Liminality, temporality and marginalization in Giorgio Mangiamele’s migrant movies”, in Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 1, no. 2, (2007). Now see also Gino Moliterno, “Cinematic Intertextuality and Comic Allusion in Giorgio Mangiamele’s Ninety Nine Per Cent” , Screening the Past, Issue 27, 2010, http://www.latrobe.edu.au/screeningthepast/27/intertextuality-mangiamele-ninety-nine.html. It’s heartening to note that, even more recently, Silvana Tuccio has submitted a doctoral thesis on the films of Mangiamele at the University of Melbourne.

[3] There has continued to be confusion about whether Clay was the second or third Australian film to be invited to Cannes after Charles Chauvel’s Jedda (1955). However, the official Cannes records show that Walk into Paradise (Lee Robinson, Marcello Pagliero, 1956) appeared in competition in 1956 and therefore preceded Clay (see record online at <http://www.festivalcannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/3577/year/1956.html>, accessed 7 July 2011).

[4] Bruce Hodson, “The Carlton Ripple and the Australian Revival”, Screening the Past, November 2008; http://www.latrobe.edu.au/screeningthepast/23/carlton-australian-revival.html.

[5] Mangiamele’s Crocean orientation was noted and underscored by Carlo Laurenzi in the Corriere della sera article (op. cit) which was reporting on the screening of Clay at Cannes. Presumably paraphrasing Mangiamele’s own comments, Laurenzi wrote: “Come nessuno al mondo Mangiamele è persuaso che il cinema debba disancorarsi dalla socialità, dal documento, dall’umorismo, dal senso commune, da tutto ciò che non è purezza poetica. Può darsi che Mangiamele sia consapevolmente crociano: è nato a Catania e ha studiato a Roma, dove, non più di tredici anni fa, frequentava la scuola di polizia nel quartiere Flaminio. Noi, che ignoriamo quasi tutto sui corsi di insegnamento nella scuola di polizia, non escludiamo affatto che l’estetica di Benedetto Croce sia onorata in quell’accademia”. [Like no-one else on earth, Mangiamele is convinced that cinema needs to de-couple itself from social comment, from documentation, from amusement, from the commonplace, from everything that is not pure poetry. Perhaps Mangiamele is self-consciously Crocean. Born in Catania, he studied in Rome where, some 13 years ago, he joined the police school in the Flaminio quarter. Having no idea what is taught at police school, we cannot discount the fact that the aesthetics of Benedetto Croce may have figured prominently in that academy.]

[6] NFSA, Title no. 746025. The manuscript is undated. On the title page, above Mangiamele’s Rathdowne studio stamp, appears in printed handwriting: “ARGILLA/soggetto cinematografico di Giorgio Mangiamele/tradotto in inglese col titolo ‘Clay’ [ARGILLA/ film treatment by Giorgio Mangiamele/translated into English under the title ‘Clay’]. The English translation is undoubtedly NFSA Title no. 728093. In similar handwriting (and above the same commercial stamp imprint) the title page reads: “Clay/screenplay by Giorgio Mangiamele.” Mangiamele’s knowledge of English was good but not faultless, so the extreme accuracy and fluency of the English version suggests that the translation could not have been made by Mangiamele himself.

[7] In the event, a car wheel splashing through the puddle at the entrance to the compound comes to be used almost obsessively in the film as something of a punctuation device. Attention is even drawn to its repeated appearances on the soundtrack where we hear the male of the couple who come to buy some pottery actually say to the father: “why don’t you fill in that puddle at the entrance of the place?” Given such highlighting, it’s interesting to speculate whether Mangiamele may not have been recalling the puddle that the car drives through at the school entrance at the beginning of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les diaboliques (1955), a film similarly obsessed with water and water imagery.

[8] Reported in “They’re a Dedicated Set”, article by Bob Ross in The Sun, 6 June 1964, p. 23.

[9] That filming had already begun by early June 1964 is confirmed, and illustrated by two photos, in the Sun article (ibid).

[10] Phone interview, 22 September 2010.

[11] Colin Bennett, ‘Clay: A new local feature’, The Age, 12 December 1964, p. 37 and David Bornstein, ‘The Film that Giorgio [of Carlton] made’, Herald, 12 December 1964, p. 26. Interestingly Bornstein’s article is one of the very few that reports that Mangiamele’s new film was shown together on a double bill with his earlier Ninety Nine Per Cent.

[12] Chris Tsalikis, phone interview, 22 September 2010. The film attracted a very positive review from V. Basile in the Italian newspaper, La Fiamma, which also stressed its artistic qualities. Basile suggested that parts of the film, such as the opening sequence, reached “le vette della più pura arte cinemetografica”[the peaks of the purest cinematographic art] but conceded that the film was not without its faults. Nevertheless it concluded that “Mangiamele ha ancora una volta dimostrato che dietro la macchina da presa è un maestro,” [Mangiamele has again given proof that behind the camera he is a master]. See “Clay: un altro successo di Giorgio Mangiamele,” in La Fiamma 19 December 1964, p. 6.

[13] The review appeared under the rubric of “Remarkable Films made in Melbourne” in The Advocate, 24 December 1964, p. 19.

[14] In the wake of the premiere there was much talk about the film going to Berlin. Reports in La Fiamma on 19 December 1964 and 14 January 1965 stated unequivocally that the film would be representing Australia at the upcoming Berlin Film Festival.

[15] The fact that the film had been accepted for Cannes was reported by Andrew McKay in his article, “The Film Man of Rathdown [sic] St.” in The Herald, 27 March 1965, p. 6, which also recounted how the Commonwealth Government had refused to contribute the £400 necessary to add the French subtitles. The film’s selection for Cannes was also communicated by Robert Clarke, one of the actors and a technical assistant on the film, in a letter to the editor of The Bulletin, April 3, 1965 (p. 40).

[16] The screening of the film for Italian journalists aboard the ship in Naples is reported by Bruno Rubino in his article “L’Australia a Cannes sarà rappresentata da un nostro emigrato”[ Australia will be represented at Cannes by one of our expatriates], in Domenica del Corriere 16 May, 1967.

[17] Phone interview, 21 June 2010.

[18] Variety, 23 December 1964, p. 7.

[19] Variety, 26 May 1965, p. 7. But some of the French papers, among them Le Monde and Le Figaro had been even less impressed by the film. See Andrew McGregor’s account in his Film Criticism as Cultural Fantasy: The Perpetual French Discovery of Australian Cinema (Bern: Peter Lang, 2010), pp. 39-40.

[20] By the time it was screened at the festivals the film had already received the Silver Award in the General Category, the Silver Medallion for black and white photography in the Kodak Photography Awards and the Silver Plaque in the black and white category of the Australian Cinematographers’ Society Awards.

[21] Boyd’s impassioned plea was reported verbatim the following day in The Age (5 June, 1965, p. 5): “We need Government acknowledgement for this art and support for it. […] We need schools for training artists in the film – directors, writers, actors. We need at least one university to open a course in the art of the film. In this field, as in so many other things, we are bursting wih unrealised and frustrated talent..” All the more curious then that in his extensive “Summing Up the 1965 Festival” in The Age 26 June, 1965 (p. 23), Colin Bennett failed to even mention the Australian-made Clay.

[22] In its wrap-up of the Sydney Festival The Film Weekly reported that “‘Clay’ was possibly the most unpopular feature of the entire festival. […] The audience was not prepared to tolerate the film’s defects just because it was an Australian feature.” 24 June, 1965, p. 3.

[23] The Jewish News (Melbourne), 9 September 1966, p. 13.

[24]“Celluloid and Clay”, TV Week, 12 November 1966, p. 17.

[25] Quoted in The Melbourne Film Festival Press Book, 1961-1966, p. 106.

[26] Since then the film has been shown as part of a forum on Mangiamele at the They’re a Weird Mob Film Festival in Sydney in 2005 and was also featured as part of a Mangiamele retrospective in Catania, Sicily, in the same year. In 2010 Australian Screen put several clips of the film online at http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/clay/ . The film is now available on DVD as part of Ronin Films’ The Giorgio Mangiamele Collection (2011).

[27] Quentin Turnour, “Giorgio” in Senses of Cinema, issue 14, June 2001 (available online at: http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2001/14/mangiamele_quentin/; accessed 10 July 2011).

[28] Ibid.

[29] Turnour points out the irony of Clay having been so summarily dismissed when “the dream landscape of Clay is almost that that Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) was later to penetrate”.

[30] N.A. Kovach, “Report from Down Under: The Twelfth Sydney Film Festival” in International Press Bulletin, vol. 1, no. 3 (1965), p. 35.

[31] But the stratagem is quite common in silent cinema and appears in films as different as Hans Richter’s Vormittagsspuk (Ghosts Before Breakfast, 1928) and James Sibley Watson and Melville Webber’s remarkable Lot in Sodom (1933) although it’s difficult to know whether Mangiamele might ever have had occasion to see any of these. Indeed, another possible source (closer to home) of inspiration for the opening treescape may very well have been a night scene in John Heyer’s Back of Beyond (1954) where the truck’s headlights create a similar effect as they illuminate the landscape. None of this, to my mind, excludes the possibility of Cocteau being the principal point of reference.

[32] An interesting, and surely significant departure, here, from the original treatment/screenplay where the father’s answer is given as: “He’s a man and he needs help. The rest doesn’t matter”. NFSA Title no. 728093, p. 2. Clearly Mangiamele decided to strengthen the identification while actually filming.

[33] “Celluloid and Clay”, art. cit., p. 17.

[34] Swirling leaves at a car crash appear not only in Clay but also in Sapos, one of Mangiamele’s later New Guinea films.

[35] Andrew Pike in his notes of an interview with Mangiamele conducted at his Rathdowne studio on 21 January 1970, recorded that “Mangiamele recognises no influence on his work, and would hate to be influenced – he is trying to develop his own style. He can’t define this style, however: it doesn’t come from the intellect; it is inherent in his way of seeing the subject at hand”. NFSA Title no: 599515.

[36] Raffaele Lampugnani, “Giorgio Mangiamele: Poet of the Image”, Italian Historical Society Journal, (Melbourne), January-June 2002, pp. 22-23.

[37] Film Weekly, 6 February, 1964, p. 4 and April 9, 1964, p. 9. My thanks to Adrienne Tuart for helping me track down this information.

[38] Melbourne 1964 Film Festival program.

[39] “They [the boots] reveal the plight of the man who wore them so utterly and, through his adversity, the toil and fatigue of the whole world”. Frank Elgar, Van Gogh (New York: Praeger, 1966, p. 85. This characterisation could very easily be applied to Nick’s shoes.

[40] “‘[…] art cinema’ is a post-Second World War phenomena [sic] in Australia, beginning perhaps with Clay (Mangiamele 1965)”. Australian National Cinema (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 223.