Cooking must be the most totally valid art form. Its aim is totally functional. [1]

This idea of the social role of the artist as being that of an educator/transmitter of ideas etc. in the global inter-communication system, is something that really interests me. Further, I would like to no longer regard an object as an ‘art work’ separate from other environmental images (both media and natural) but rather as visual information. [2]

Lynsey Martin began his experimental film practice in Australia during the early 1970s. His 16mm films use collage, incorporate the photographic image’s grain and its erasure, hand-painting and direct inscription on the film’s surface. Martin deals with the film’s material elements, the frame’s design, movement and the act of looking in both public and private space. His films incorporate abstraction, chance, the deconstruction of film language; they speak to the diary film and found footage cinema. Though often marked as formalist, they reveal a consideration for the marginal and invisible events that shape everyday life.

The Invisible Margins

Outside a shrinking circle of Melbourne artists and critics, Martin’s experimental 16mm cinema remains largely forgotten in Australia today, and unknown internationally. This is despite a portion of his early thinking remaining accessible in Cantrills Filmnotes (Nos 9, 12, 16, 17/18, 23/24, 29 and 30) and despite a solid enough screening program from the 1970s through to the 1990s, particularly in Melbourne. Jim Knox has described Martin’s experimental films as “some of the most extraordinary cinema ever made in this country, and still largely unknown”. [3]

This marginal cultural position is characteristic of the Melbourne Experimental film scene in general over this period, having been overtaken by Super 8, video art and new media. Martin’s screening record confirms the shifting visibility of his work in innovative film circles. His work initially screened at the Melbourne Filmmakers Co-op in 1972, and in 1982 was part of the Preston to Phillip Survey: 10 Years of Art Education and also New Cinema, New Film at RMIT’s Glasshouse Cinema the same year. But now it is totally absent from curated screening events.

Through MIMA, Martin’s work participated in 1986 as part of programs on Dreamscapes, Animation & Texture and Melbourne: The Place and in 1987/8 was included in MIMA’s National Exhibition Tour of Film and Video, screening in all the State capital cities as well as regional centres including Geelong, Albury and Bendigo. In 1990 his work was included in MIMA’s Showcase Experimenta Festival and in 1992 MIMA’s The Colour of Film program. In 1996 he participated in a screening at the Erwin Rado Theatre in Fitzroy as part of a benefit program for the Melbourne Super 8 Group. MIMA itself morphed into Experimenta in the 1990s, jettisoning its interest in experimental cinema to concentrate solely on new media work, a shift that marks the time when Martin’s films faded from public screens.

Martin reads his own retreat more as a response to semiology, which Peter Wollen brought into film theory in the early 1970s. Internationally Wollen’s celebrated article “The Two Avant-Gardes” made a distinction between a Godardian political cinema and a formalist co-op cinema, influenced by painting and sculpture that Wollen considered apolitical. [4] Martin identified more with this latter history of film art.

I felt intimidated by the hold that the semiologists had gained over film theory and analysis. With all their signs and signifiers, I felt that I couldn’t withstand their barrage, so I retreated. I felt I had nothing to be apologetic about and I felt that theory and dissection were important but their approach was somehow divorced from reality. A kind of almost clinical, scientific approach to an inherently humanistic, expressive endeavor. So I put the film aside… but kept thinking about it. [5]

Nevertheless, Sam Rohdie, for one, sought out and highlighted Martin’s work in a survey of Australian avant-garde film, linking it into the self-reflexive structural work emanating out of the London Filmmaker’s Co-Op. He also referred to the 1967 Ubu Manifesto on the Handmade Film, penned in Sydney by Albie Thoms, Aggy Reade and David Perry. “The means of image production coincides with the image produced- the films are ‘about’ scratch, incising paint and dye” [6] For Rohdie, Martin’s “carefully controlled system and structure” [7] sets it apart from the more anarchic Ubu work. Rohdie interviewed Martin for his RRR radio program in that period but the conversation never went to air and is now an un-locatable document. Martin describes his own practice as artisanal, occupying an uneasy gap between cinema and art. As a self-funded artist he was:

an active participant and contributor to the Experimental/non-narrative/independent /avant-garde/abstract film milieu in Melbourne of the late 60s to late 80s, a movement generally unknown to the general public and indeed to much of the prevailing film as art, film festival, art galleries scene. My films are essentially self-made, self-produced in the sense that as an artist, I aim to exercise control over as many aspects of the medium that I possibly can. That is production direction, photography editing, sound etc. [8]

I became reacquainted with his work in 2013 when Leading Ladies (1975-9) was included in a historic program of Australian experimental film at the Alternativa Film and Video Festival in Belgrade, Serbia. Martin’s work had screened in New Zealand in 1982 in a program organized by Corinne and Arthur Cantrill. In 1985 he screened at the Arsenal in Berlin and in Osnabruck and Frankfurt. Earlier, in 1976 Martin presented his work at an Open Screening at the London Filmmakers Co-Op during a visit reported on by Martin in Cantrills Filmnotes [9] . During this period in London Martin recalls making contact with Stephen Dwoskin who showed him around the Royal College of Art. He also recalls Malcolm Le Grice commenting on his films:

“Your films are interesting, but they would have been so much better, had they been made here in England”. Similarly, I have a very clear recollection of what Arthur Cantrill said when I told him, when I returned to Australia. He remarked, “That was a very easy thing to say”. [10]

Martin had left in January for “a self-imposed exile for four and a half months” [11] which ground to a halt a number of filmmaking projects. A re-configured Frames was not re-visited until 2007.

Understandably, despite a measure of public exposure for local work, Australian film culture has been serviced by an international canon that privileges the British and North American avant-garde. It is these films, for example, that were first acquired in the 1970s and 1980s for study through the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) Non-Theatrical Lending Collection in Canberra. The international status of this canon was built on a sustained and networked level of public exposure and critical examination not readily available to Australian experimentation. In a pre-digital world location and population size alone impacted Australian work’s limited access to this process. Despite the documentation provided by Cantrills Filmnotes, this work is not seen. Elsewhere I have explored how even this important magazine confirmed the status of its editors and originators ahead of those who populate its pages in this environment. [12]

Such discounted space is not unique, although the views that produce it can be contested. When viewing a retrospective of Dutch experimental film at the Rotterdam International Film Festival in 2004, I was struck by both the lack of attendance by international guests and the parallel investigations evidenced in the program, assigned and identified with other artists in the international canon. A program of Balkans structuralist film viewed in Belgrade, Serbia in 2013 played out a much more politicized formalist cinema than the more well-known British structuralist films to which it can be compared. Ivan Galeta suggested in Belgrade that formalist film had actually originated in Zagreb at GEFF as part of the 1960s anti-film movement, through artists like Mihovil Pansini. [13]

Background

Martin was born in 1951. He studied graphic design, photography and film at Preston Institute of Technology and Victoria State College in Melbourne. As an “Art School” Preston’s specialty was design and painting. Swinburne’s specialty was film and Prarhan’s photography. “In those days, arts teaching institutions were independent and enjoyed a high degree of autonomy and following the British model, were called colloquially, ‘Art Schools’”. [14]

He has worked in graphic design, educational film, television production and mixed media. The bulk of his professional career has been as a Secondary school teacher. In the 1970s he worked at Essendon Technical School. From the early 1980s Martin worked for 23 years in the Secondary High School system, initially at Lakeside Secondary College and later at Keilor Downs Secondary College where he taught Visual Communication and Design, Art and Art History.

Martin’s photographic obsession began with his father’s 35mm camera, a Minolta Rangefinder. This early preoccupation extended through to his tertiary education. Numerous colour and black white photographs were shot and self-developed, a foundation that later transitioned into his moving image practice.

Martin’s focus on the mundane and incidental gestures of everyday life lie somewhere between a formal and a personal autobiographical approach that begins with this gestural use of his father’s camera. When loading film rolls into this camera Martin advanced the film past the fogged area and then nonchalantly shot a couple of test images of the window in his room, in and out of focus and without looking through the viewfinder. There were also similar film run-ins in super 8 and 16mm of this same window between 1971 and 1973. This was really normal professional practice, but Martin collected this technical residue, assembling these repetitive casual half-images for the autobiographical Frames, a project that has experienced several shifts over the years and remains incomplete. Such peripheral and chance events reappear in various guises in Martin’s practice. The same material also appeared in the 3-screen version of Parts 1-6 in 1973.

Another strand of experimentation that led to Martin’s interest in filmmaking developed in the early 1960s through the collages he constructed and assembled for multimedia slide shows. He was attracted to these assemblages via photographs in American music magazines where the abstract light shows often framed the images of music idols such as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and the rock band Cream. This time appropriating his father’s 35mm slide projector, Martin reconfigured scraps of 35mm film with a painter’s toolbox he was developing through an exploration of abstract painting. Coloured acetate, ink and paint were used to engage and echo the Abstract Expressionism of Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline and Jackson Pollock. “It wasn’t long before I was doing light shows myself at High School social functions with as many school projectors that I could commandeer.” [15] These shows evolved to using as many as seven slide projectors, their screens knitted together into walls of light in relationships that expanded on the constructions of the individual slides.

Mentoring

Two critical relationships impacted Martin’s practice. His work colleague and film editor Tony Paterson was a strong technical influence while successful experimental filmmakers Corinne and Arthur Cantrill fostered Martin’s aesthetics.

Upon completing his tertiary studies Martin worked as a Graphic Designer and Assistant Director making educational films and television, exhibition design and publications. He worked with Tony Paterson, a seasoned film editor who had worked at Crawford Productions and was renowned for cutting episodes of the TV cop shows, Homicide and Division 4. This relationship across film art and the commercial sector began during the Australian Film Industry’s resurrection, in which Paterson played a key role. Paterson edited the first legendary Mad Max (George Miller, 1979) and a number of early John Duigan films including The Firm Man (1975), The Trespassers (1976), Mouth to Mouth (1978) and Dimboola (1979). Paterson encouraged Martin’s experimentation with technical advice on films like Leading Ladies and Automatic Single Continuous and by providing sound editing and equipment support.

As well as providing screening opportunities, Corinne and Arthur Cantrill edited Cantrills Filmnotes magazine, to which Martin contributed from its 1970s beginnings. Martin also attended informal film events in their double storey Brunswick home, ‘Prestonia’. On countless Sunday evenings through the 1970s and 1980s, the Cantrills organised informal home screenings of 16mm experimental films. These were programs that Arthur had assembled to screen to his students at Melbourne State College the following week, often assembled from those available at Canberra’s NFSA Non-Theatrical Lending Collection. Such events included works by Robert Breer, Pat O’Neill, Oscar Fischinger, Malcolm Le Grice, Kurt Kren, Peter Kubelka, Lotte Reiniger, Jeff Keen, Berthold Bartosch, Bruce Conner, Su Friedrich and Stan Brakhage.

As it was for others like myself, Michael Lee, James Clayden, Chris Knowles and Maggie Fooke, this was Martin’s de-facto initiation into experimental film. This induction ranged through viewings of formalist work, personal cinema, avant-garde animations, artist film and video and innovative documentary. In the 1980s at the edge of empire we received this amalgam of British, American and European concerns as the international canon. Eventually Australian experimentation was incorporated into this accesible archive.

The Films

Martin has completed 9 films from 1969 to 2017, all self-funded. A substantial portion of work in the expanded cinema thread remains incomplete through lack of funds, time and resources. Even with the stand-alone single-channel works concentrated on here there is often a multi-year gap between initiation and completion. Whitewash, for example was begun in the late 60s when he was still living at home as a teenage secondary school student. Upon his retirement from teaching in 2007 he has returned to a series of earlier projects from the 1980s and 1990s. This has been made more difficult, having been diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease, which has required a number of hospitalisations to manage over the last few years.

Martin’s early work is available from the NFSA Non-Theatrical Lending Collection. This is the same collection used by Arthur Cantrill to introduce the international canon of experimental film to his students. Martin’s films available there are Approximately Water (1972), Whitewash (1973), Inter-View (1973), Leading Ladies (1975-9) and Automatic Single Continuous (1982). The Melbourne University Library also has a copy of Leading Ladies. These films, with Light and Dark (2006) form the body of this analysis, discussed in order of completion.

Approximately Water (1972, 4 minutes)

This film emerged out of a two week film workshop organised by Corinne and Arthur Cantrill while Martin was a second year design student at Phillip Institute of Technology:

We wanted to give the workshop an orientation towards new cinema concepts – film as a means of personal communication, rather than a general filmmaking course imitating film industry procedures. The idea was not only to make film, but for the participants to see as much new work as possible, to meet other filmmakers, and to be aware of the relationship of film ideas/concepts to style and technique. [16]

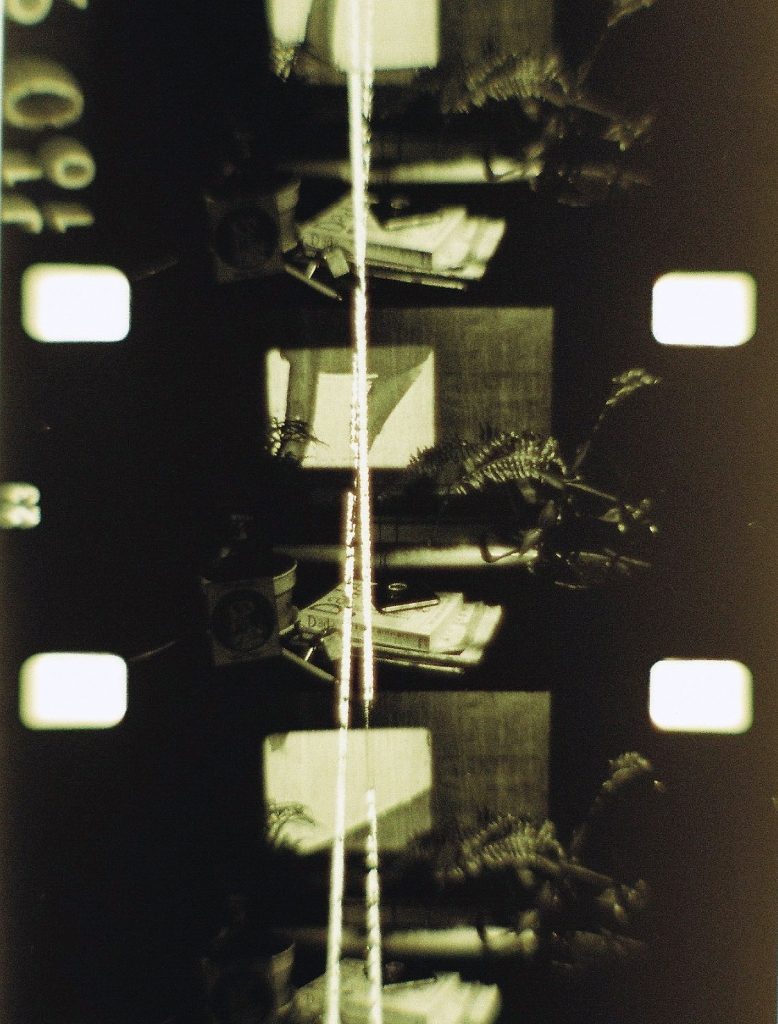

Approximately Water is a straightforward recording of a stream of tap water in negative with a jazz-rock music soundtrack that evokes running water. The stream was recorded with one continuous take using a stationary camera. Over the film’s duration, different direct-on-film techniques such as dyes and scratches are layered over this originating movement.

This conceptual work of art foregrounds the materiality of 16mm film and the mechanics of film projection. The film’s content re-iterates the act of a strand of film streaming through a film projector or camera gate. This is this film’s subject; a time slice of running water. When you scroll through the film over a light table every drop of water that passed by the camera lies before you in sculptural form. Each drop is recorded on consecutive frames. The stream of water is transposed to the field. Martin points out: “What I was interested in was the old thing of abstraction vs. reality and the use of the mundane, day to day phenomena as a vehicle of expression.” [17]

This dialogic flow between water, time and film introduces in rudimentary form what Corinne and Arthur Cantrill later explored in their three colour separation landscape film Waterfall, completed in 1985. The politics of these films differ. The Cantrills transport Martin’s mundane view of urban everyday existence into a picturesque Australian landscape. Their bush scene references the privilege of British landscape painting and the dining rooms and studies in which it was hung, while Martin remains steadfastly stationed at a routine fixture servicing the suburban garden.

For Michel Foucault, the garden is a heterotopia, a manufactured microcosm of sampled global environments and plants. Melbourne’s suburban gardens are generally centered by the British lawn, fringed by a mixture of introduced and native flora and maintained by the garden hose and lawn mower. Such a suburban garden is a liminal transitory space fashioned into the most unobtrusive and repetitive of the garden’s forms.

Jorge Lorenzo uses a similar reflexive structure to Approximately Water to political effect in his recent On the Road by Jack Kerouac (2013). Delivered from a muted Mexican outsider position Lorenzo demolishes the beat generation’s revered position in contemporary Western Art by precisely transforming Kerouac’s text into a cascade of information flow. [18] Approximately Water’s politics sits somewhere in between Lorenzo and the Cantrills, in a heterotopic space that both de-familiarises and reduces the commonplace to a perceptual exercise in pattern recognition.

Whitewash (1973, 4 minutes)

“Out, damned spot! out, I say!”.

Lady Macbeth in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606)

This film’s soundtrack is appropriated from Pink Floyd’s the “The Narrow Way”, a track on the studio half of the 1969 Ummagumma Album. This song is written and performed entirely by David Gilmour, using multiple overdubs to combine the instruments played. Such sonic overdubbing is a similar technical strategy to the visual layering Martin employs in both Approximately Water and Whitewash.

A recurring theme in Martin’s work rears its discordant head here. This is the gap between the conception, beginning and completion of a work. His practice is intermittent. Projects can lie dormant for significant lengths of time: “conceived as a piece of handmade film in 1969 it wasn’t until a 3-day week-end early in 1973 that I finally got down to realizing the piece”. [19]

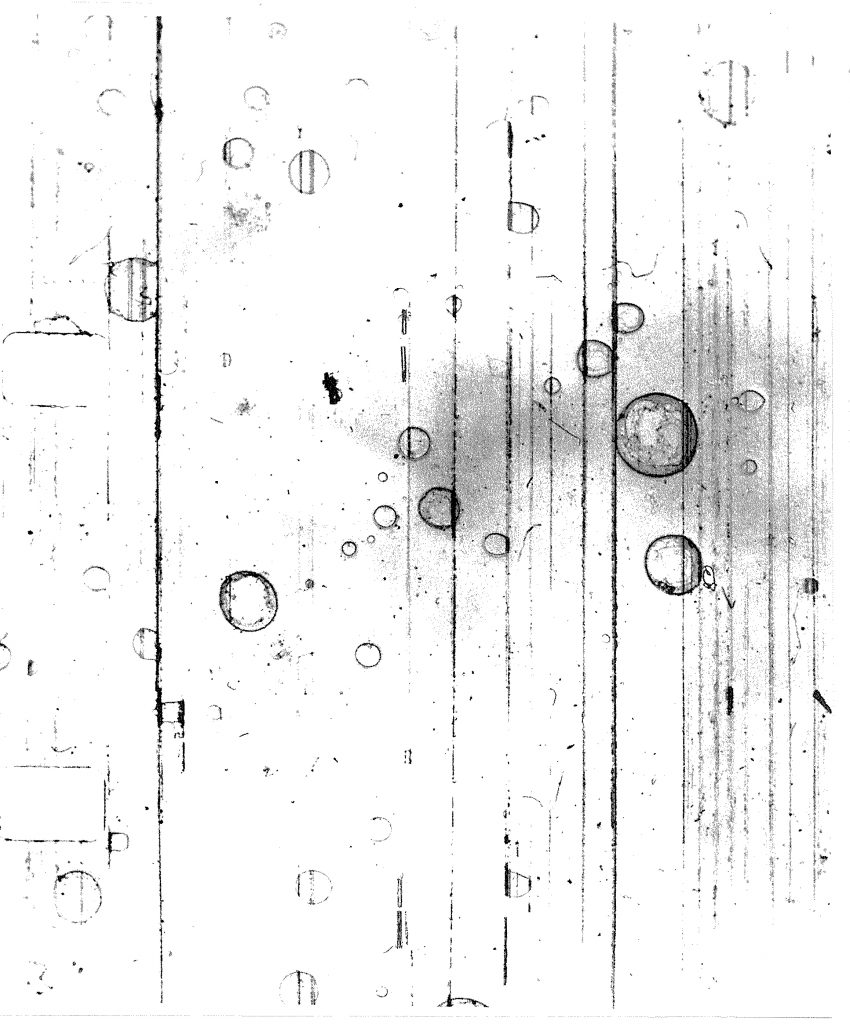

Like Martin’s career, the film approaches a level of constructed invisibility, consisting of scratches on clear film stock, produced using incising and sanding instruments. These inscriptions are ephemeral and fleeting, often difficult to see. Norman McLaren has similarly drawn directly onto the film’s surface with the larger 35mm format instead of 16mm, but Martin’s aesthetic is closer to Len Lye’s cameraless animation. Lye’s Particles in Space (1966) and his later incomplete Tal Farlow (1980), published after Whitewash, come to mind. Martin describes Whitewash as not having a beginning, middle or end. Its first inscriptions are vertical lines, which then shift to horizontal movements and other effects like hole punches and the pulsing effect of scratching intensely on one frame and then leaving the next frame blank. There is also the subtle patterned residue of watermarks created by leaving sprayed water to dry on the film after being over-sprayed with a fixative.

The images of the film documented on the pages and cover of Cantrills Filmnotes in 1973 are much sharper than the patterns available in a viewing of a print of the film. These stills have been produced from the film’s original scratched material, shot with light from the side of the frame as well as from behind. These images have a three-dimensional quality that reveals the incision’s cavity and its removed residue. The sharpness and depth of this original material is not available in a print of the film. These artifacts are as clearly visible in any print of any film. This original Whitewash is materially different to its fogged-like copies. Essentially this film, through its reproduction, white-washes itself. Every new generational copy made of it is whiter than the original. This organised erasure stresses an effect of diminishing returns, an essential characteristic of analog film that sets it apart from the digital moving image. In the digital, each copy clones the original. No information is lost. This film’s content is the material process of whitewashing. Whitewash sets in train a serial self-mutilation. If we inscribed our bodies in this way, it can be considered a form of traumatic self-harm.

Martin’s title choice opens up a number of practical, social and political meanings for reading the film. Whitewash originally described a low cost lime and chalk based paint used on farms to aid in the sanitation of equipment. It was also used on the interior and exterior of worker’s cottages in Britain and Ireland. During the Second World War ‘whitewash’ camouflaged military equipment in winter conditions. As a laundry additive it brought a bright tinge to boiled white textiles.

Such uses migrated into popular culture as metaphor to describe one-sided sporting contests, for example, or the cleaning up of one’s political profile. The political ‘whitewashing’ of a person or group, indicated the suppression of any negative connotations attached to that individual or organisation. In contemporary culture ‘whitewash’ is also used as a derogatory term describing a minority that has successfully assimilated into western society. The recent academic publication that foregrounds the term, White-Washing Race [20] argues that racist discrimination still operates in contemporary American culture.

In Australia ‘whitewash’ also insinuates racism. It plays out in gutted form those assimilation programs of a racist White Australia Policy impacting both migrant and indigenous groups still implicitly operational in early 1970s daily life. There is a powerful scene at the beginning of Phil Noyce’s Rabbit Proof Fence (2002) that demonstrates its originating fervour in relation to indigenous Australians. Neville, Protector of Western Australian Aborigines in 1931, in a slide slow presentation demonstrates how half-caste aborigines will be ‘bred out’ through the whiter offspring of succeeding generations. This is Neville’s demonstrated definition of the government’s assimilation policy.

Whitewash is read here as an ethical yet inarticulate revulsion against such racist views. The skin of the body, the skin of the film. The film performs an act of self-mutilation by a young white male entering the vexed political situation of implicit white privilege that is nevertheless, given his class and age, inaccessible to him personally. Inside the formal, the personal returns.

Inter-View (1973, 25 minutes)

Certainly such revulsion takes clearer form in Martin’s next film Inter-View, where he directs the same strategies of erasure refined here at newsreel footage connected to the Vietnam War and the numbing effects of propaganda resident in the nightly television news.

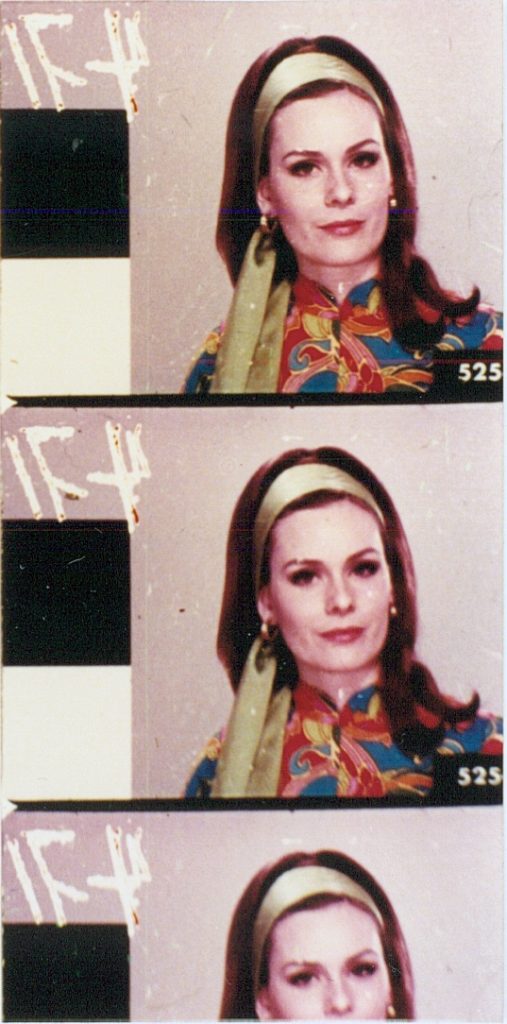

Inter-View is in two parts, the first has been shot off the television screen with a Bolex 16mm camera, most likely Paterson’s, and frames news events linked to the Vietnam War. Television monitor’s rolling bars are intermittently visible. The second part is comprised of original television broadcast material, discarded black and white out-takes, male and female headshots of interviewers and interviewees. For this second part of the film, Martin did not scratch the original broadcast footage, which had a magnetic stripe soundtrack but had a print made, which he then systematically mutilated. The film is silent, despite the voice dependent nature of the material.

This film’s duration and silence imposes a different looking on the viewer. Martin enlists a Zen saying to make his point: “If something is boring for 2 minutes, try it for 4, if still boring after 4 try it for 8 and if still boring try it for 16 and so on. Soon one discovers it is not really boring at all”. [21] Such durational strategies have also been used to effect by James Benning’s 1970s structural cinema. Benning found creative ways of reintroducing the social through the structure of feature length works such as Landscape Suicide (1986) and North on Evers (1991). His long durational shots demonstrate how trauma may be denied and forgotten but remains implicitly traceable within the landscape. [22] Is there a trauma embedded in Martin’s film?

As we watch Inter-View our interest in deciphering what the talking heads say dissipates. We are drawn to gestures, eye movements and pauses. We look for new clues. Now parts of the image are systematically scratched away, drawing our attention to incidental features such as the microphone, an isolated hand or a mouth. The rough and shaking texture of these erased images takes over. The frame of one such isolated mouth is the cover of Cantrills Filmnotes No 16 (December 1973).

Martin understands this image removal with a razor blade as an angry response to the politics of the time. His incisions attack the manipulative nature of the originating newsreel material. This response is reminiscent of the similar excision of American soldiers from the frame by the Cuban documentary filmmaker Santiago Alvarez in his 1969 short film: the 79 Springs of Ho Chi Minh.

Alvarez performed an aggressive act of bewitchment on his film material. He etched out the eyes of American soldiers in Vietnam War footage, like a shaman might place needles in a voodoo doll. Alvarez had experienced the U.S. bombings of Hanoi directly during a visit there, and survived in a rudimentary fallout shelter. Having already built a reputation as a committed political documentary filmmaker, enabled by his country’s critique of U.S. Imperialism, [23] Alvarez’s incisions perform his politics.

Martin comes at his mutilation from a different cultural position. He addresses the perceptual impact of a local propagandist press at its pre-reflective source by physically removing its mark and producing a gap. For Martin’s generation the Vietnam War was a very real and direct experience that never left. National media delivered the telling possibility of being sent into combat as an 18-year-old. Australia’s support of the United States was serviced by a conscription system determined by one’s birthdate. You were conscripted by chance, by a roll of the dice, announced on the radio like a macabre Tattslotto result. In 1972 the Australian Labor Party’s election victory, led by Gough Whitlam, ended Australia’s participation in this war. Those that had gone to fight and returned were not embraced as heroes. Some were spat upon. Many returned soldiers played out the fractured and traumatised personal lives of angry and broken men. Inter-View stands as a testament to this situation.

Martin’s looking is deviant to the culture’s required mean and replaces the crisis of military service. If one is young, white and male, living in Australia’s affluent suburban sprawl and uneasily critical of this privilege, how do you respond? If drawn to a politics that rejects an unwanted war into which one is invited to sacrifice one’s life, what do you do? Martin’s response is a critical visual language that talked to this situation’s visceral impact on one’s body and senses. This response forces a different way of looking. Such a language’s syntax and address stands in contrast to the master’s house, the language of the dominant culture. Though dismissed by Wollen, such a line of experimentation is implicitly political and of a markedly different register than achievable through any explicit documentary form.

There exist four versions of Inter-View. The first version is the 16mm original with a degenerating magnetic soundtrack. Its brown magnetic strip contains the questions and answers, the conversation that is denied the viewer. Secondly there is the systematically scratched and fragile copy, with its grooves, residue and uneven surface with no soundtrack. Thirdly there is the projection copy, which has been printed from this second mutilated roll of film. Its quality is further diminished. Its surface is smooth and clean. The earlier incisions are now only a photographic record. The fourth copy is a digital transfer from this projection copy, now eternally reproducible without further change. It could be productive to project these artifacts side by side, or slowly scrolled through over a light table: the original, the copy and the clone. Is this how a wound heals?

Leading Ladies (1975-9, 5 minutes)

In 1974 the Education Department decided Tony and I would be more gainfully employed at Collingwood Technical School, where the Electronics Department had set up a black and white closed-circuit television station. Collingwood Technical School was considering setting up a 16 mm projectionists’ licence training facility in opposition to RMIT, and procured a large box of discarded film leaders from the State Film Centre. When the school decided to scrap the idea of running the course, the leaders were to be thrown out. Having made films using ‘found’ footage, I recognised the leaders as having the potential to become a film and asked if I could have them. Thus, Leading Ladies was born. [24]

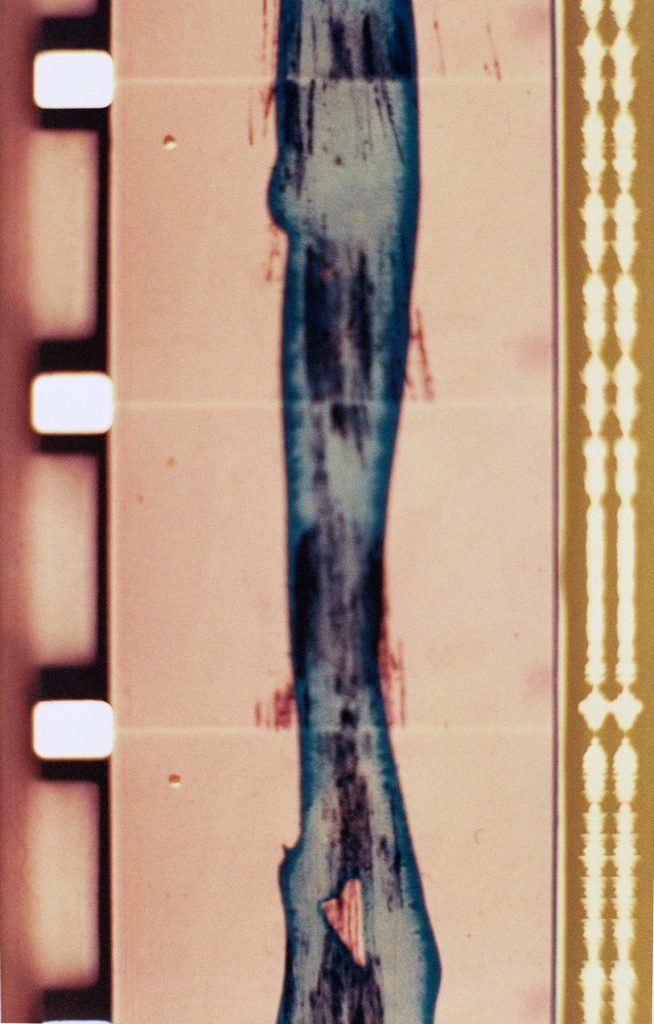

Leading Ladies assembles those images placed at a film’s head and tail by laboratory technicians for quality control. These are not the leading ladies chosen by the casting department or hired on the director’s couch, but nameless women accessible to the proletariat servicing the production line. This material remains hidden during normal cinema projection but here becomes the film’s subject. These are images of women’s faces, countdown leader, other laboratory reference strips, lettering and printer sync marks. The countdown numbers enabled projectionists to focus the film before the real action began. The women’s faces, referred to as ‘Kodak Ladies’ or ‘China Girls’ are colour images spliced into the films to check the colour balance and exposure of the prints, to ensure that the film processing is operating within industry standards.

As they were not for viewing purposes but to be inspected over a light table, these images only spanned a handful of frames. They are only available for a subliminal they to for a fraction of a second of screen time. The women’s faces are chosen to help fine-tune the print’s skin tone and colour. These ‘China Girls’ regularly held a colour bar, to further aid in colour grading. These faces are consistently easy on the eye, likely the residue of male dominated workplaces. The women’s white skin can remind us that exposure and colour in cinema has been calibrated for white skin, not black or brown. Such hidden consequences of racism can be the most coercive, as they are woven seamlessly into the fabric of daily life.

The soundtrack is similarly compiled from the artifacts of the laboratory’s printing and processing operations; clicks, buzzes and scraps of effects. These artifacts lead to a measured dialogue between sound and image. The sound track took as much consideration to edit as the image, using an EMS synthesizer, with a final mix constructed again with the assistance of Tony Paterson and his studio equipment.

Martin had been able to use Tony Paterson’s flat-bed editing table to assemble Leading Ladies, as well as his Bolex to shoot the film’s titles. In the title Martin dedicates the film to Bruce Conner’s Cosmic Ray (1961), although he had only seen that film after he had nearly finished Leading Ladies, which he makes clear in the dedication.

I have dedicated Leading Ladies to Bruce Connors (sic) Cosmic Ray (b & w 1961), the two films are similar in some respects, although I had not seen Cosmic Ray until 1976, when my film was nearly finished. [25]

This is a surprising and ambiguous dedication. Clearly Martin recognised an affinity with Conner’s work but he had come to it through his own creativity and political position. This seems an equivocal gesture delivered from the margins of the margins, an even more denied practice that Conner’s itself, an erasure of Martin’s own originality and an acquiescence to the subsidiary role that Australian artists find themselves occupying in the 1970s.

Automatic Single Continuous (1982, 9 minutes)

This is a formal exercise in which chance is a structural element. The title refers to automatic exposure by the camera, the three single takes, the continuous recording of a scene with the camera analogous to the human eye. [26]

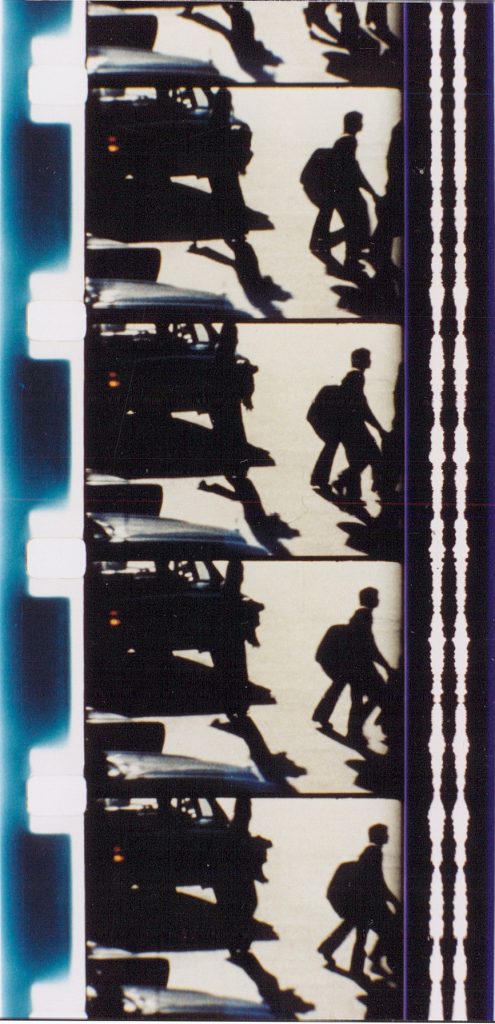

Automatic Single Continuous was recorded in 1982 at Melbourne’s iconic Flinders and Swanson Streets intersection above the traffic from the elevated square that used to sit opposite Flinders Street Railway Station before the current Federation Square’s construction. It was filmed at three separate times of day, two in daylight and the last at night. The sounds of traffic, co-edited with Tony Paterson, constitute the soundtrack.

The camera pans move effortlessly over the intersection catching legs, faces, light-poles, shadows, silhouettes and the uneven bitumen between the tram-lines, all abstracted elements linked seamlessly through the camera’s constant movement. The camera rests behind a policeman’s head orchestrating traffic. His cap is pure white. It is a hot day. The sequence completes with a skyward pan. The concluding night sequence has related camera moves and further benefits from the abstracted movement of car lights that bring the direct on film techniques of the preceding works to mind. The car lights are used like a luminous pen to write the film.

Here Martin transports the kind of perceptual events imposed on the viewer in Inter-View into the street. There is a comparable rhythm to the gestures and clicks of the direct on film works and the camera-eye’s encounter with public space and much more unstable than Benning’s settled inspection of the landscape. The viewer’s roaming eye becomes the subject of the film. We are inside the body. Martin’s camera movement suggest the same saccadic rhythms, scans and double takes that the eye performs effortlessly in mapping three-dimensional space. These are the pre-reflective perceptual performances that Merleau-Ponty identifies before critical thinking occurs:

My field of perception is constantly filled with a play of colours, noises and fleeting tactile sensations which I cannot relate precisely to the context of my clearly perceived world, yet which I immediately place in the world, without ever confusing them with my daydreams. [27]

In 2012 in Belgrade I saw a retrospective of Serbian filmmaker Ljubomir Šimunić small gauge works from the 1970s. The films reminded me of Automatic Single Continuous. I wrote that Šimunić:

glimpsed everyday street scenes write the kind of eye movement across the frame that the Situationist city dérive elicited in chance walks and taxi rides through the city. What is documented here is a new way of seeing borne from city life, where reflections, the car’s mobility and the double images offered by both the taxi and shop window are inscribed onto the viewer’s sensory cluster. The layered speed of Šimunić’s visual writing also predicts the compacted grazing and sampling response to the tidal wave of visual media that today immerses the everyday, both on the street and online. [28]

The same is true of Lynsey Martin’s Automatic Single Continuous. Though both offer indelible demonstrations of the perceptual impact of city life none of these films are considered part of experimental film’s canon.

Martin’s material was originally shot on Super 8 and blown up to 16mm on the Melbourne State College JK Optical Printer, where Arthur Cantrill was Associate Professor and taught film. The film has lost some of its original luster, having acquired a red tint. This is a result due from the breakdown of dyes in the film’s emulsion. Dyes fail over time. They decompose because of temperature, light and through chemical reactions to materials within the dyes themselves. In the 1980s Cyan dye was particularly unstable and its breakdown lead to affected films gaining a reddish tint.

Light and Dark (2006, 12 minutes)

Where Automatic Single Continuous moves Martin’s perceptual riffs into public space, the black and white Light and Dark, completed in 2006, moves them back into the intimate and dark recesses of a private living space.

The film was started in 1973 when Martin moved out of his parent’s home to house-sit the Cantrill’s Brunswick residence while they lived in Oklahoma where Arthur had secured a teaching position. Light and Dark is better described as sepia than black and white. It was shot on the cheaper black and white film but printed onto colour print stock by the laboratory. Consequently, the film has a brownish tinge that approaches a traditional sepia tone.

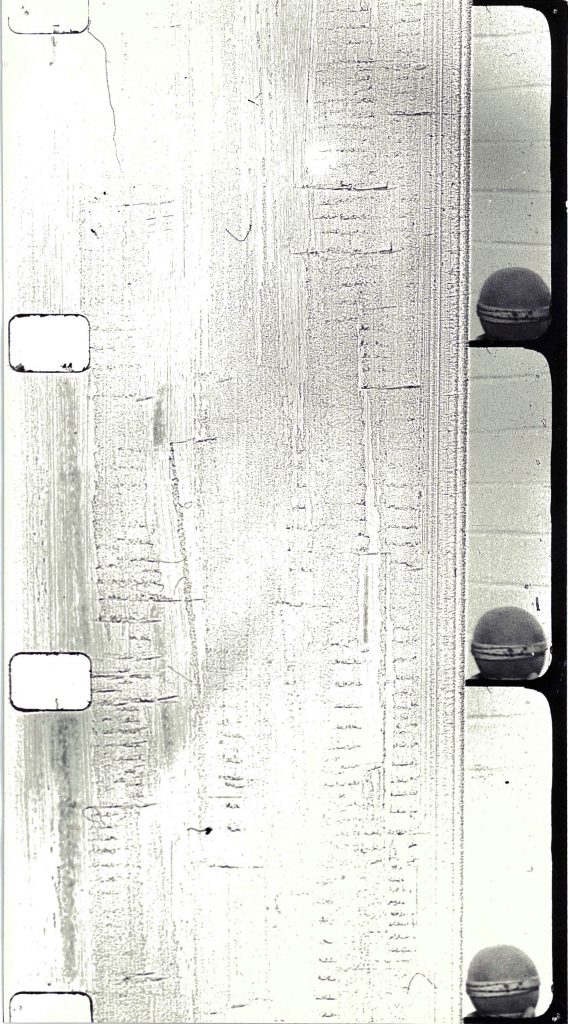

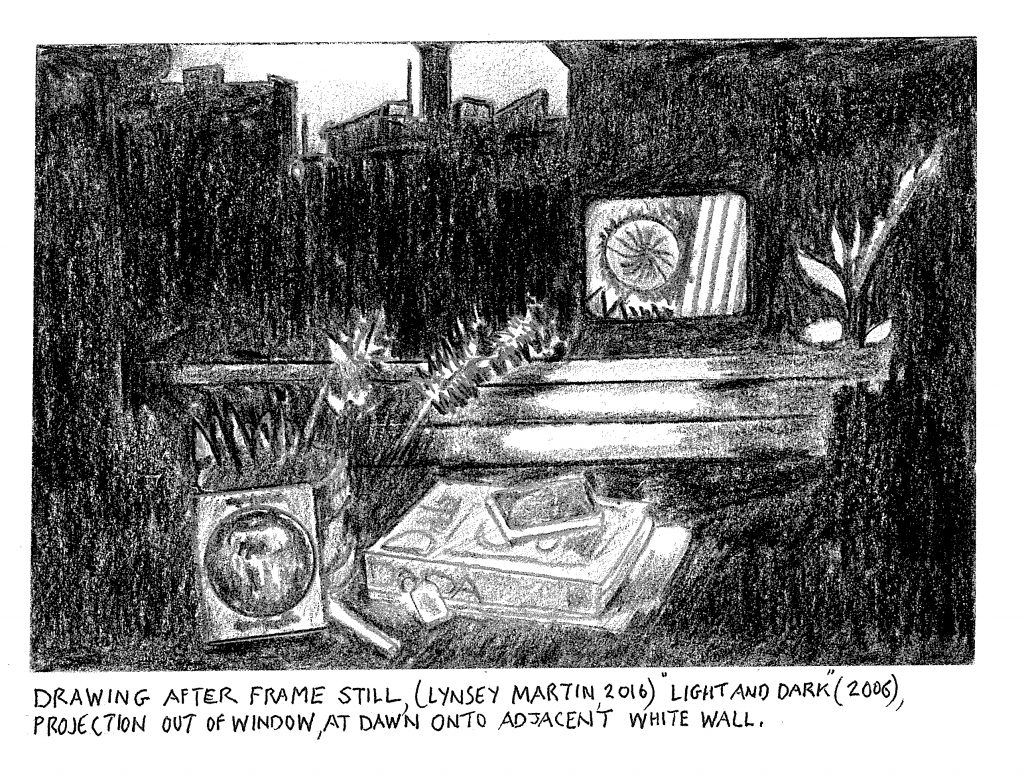

Light and Dark was completed when Martin emerged out of a bout of deep depression, decades after it was shot. It was shot towards and out of the window of the room from which he was house-minding ‘Prestonia’. A scratch film reminiscent of Whitewash is projected onto the wall and onto the window’s blinds. Scratches are added to those on the film inside the film. There are layers of design on the film’s surface and inside the photographed image, suggesting the kind of disorientation and echo presented on entering a hall of mirrors. It is as if Martin has transformed this living space into a large Camera Obscura. We are resident inside a moving image camera and simultaneously outside it. Light and Dark appears shot at night. What is conjured up is better described as a liminal space ‘beyond’ daylight. It is a dark and foreboding work evincing a gothic feel often found in a Brothers Quay animation.

The window onto which these moving images are projected faces west. There are three takes of the window and in the last the blinds roll up and the film projects through into the darkness onto the brick wall next door. These shots are framed like a still life, with ferns visible, a book about Dada and an image from a Robert Crumb cartoon. Are these cryptic clues? The insertion of Crumb suggests some kind of trauma. Yet the film’s design and the design of this shot in particular reads more like a statement about legacy and tradition, placing the film somewhere between formalism and representation. The film verges on pure abstract at times to pull back to a library of effects. These effects include sections of countdown leader, flicker and pieces of Letratone glued to the film. These are artifacts from, and traces of, Martin’s design teaching.

Slowly scrolling through these sections over a light table reveals their intricate, detailed and considered patterns. Clearly the film was assembled with consideration from this dormant state. Here the hand drawn fades and strips of Letratone are visible as balanced stanzas of graphic design. As a visual communication and design teacher Martin delivered an emphasis on technical drawings, finely crafted and accurate design, the clear and uncluttered presentation of information. The found image, so much part of Inter-View and Leading Ladies was also part of the curriculum he communicated to his students through Duchamp’s ready-mades or Warhol’s pop images. This is all visible here in Light and Dark as musical score.

Michel Foucault used the term heterotopia to probe spatial difference. Martin’s patterned film rolls provide an ‘other’ space and language. Like a library or a cemetery, its contents are linked to slices of time, to be translated and in this case re-animated by threading them through a film projector.

Martin’s sequences of dormant design codes have a precise and determined function in relation to cinema yet deliver a very different language when viewed as scrolls. Foucault’s assertion in his fifth principle “that heterotopias presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable” [29] both describes and positions this scroll-cinema interface and the re-animation that is performed across it.

That Light and Dark was initiated in 1973 and completed 25 years later defines and overwhelms this film and tests its content as a forgotten memory. Somehow the film folds in on itself, embracing all that frustration and darkness of the lost open-ended unfinished works. The period of its making bridges all of it.

This straddling also marks a turn from analog to digital practices, and a shift in how 16mm films are received. 16mm film has moved from participation in an underground artist sphere’s communal dialogues to the realm of the unique inaccessible artifact or performative event. Martin’s practice makes use of glitches and artifacts that produce distinctions between the original and the copy and it arrives now at that technical moment when the digital clone prevails.

The Contemporary Cloned Moment

Martin has developed a pre-reflective perception-focused moving image practice. His filmic language is grounded in the technical and the micro level of the frame and its image clusters rather than the filmed sequence of photographable events and its inherent truths. When the photographed image is available in his work it is acted upon, de-stabilised, to be mutilated and blurred.

Having familiarised himself with this language’s rhythms and effects in Approximately Water and Whitewash he has indexed these rhythms in relation to the impact of mass media, (Inter-View) to the architecture of public space (Automatic Single Continuous) and then personal space and memory (Light and Dark). Within the marginal and colonial dimensions of this practice heterotopic spaces stack up like a series of Russian Matryoshka nesting dolls. Martin’s practice links back into the garden and suburbia, racism, military service, depression, surveillance and traffic flow.

Foucault has stated that the cultural meaning of heterotopias shifts over time. Can this mean that Martin’s historically marginal practice can now garner a new relevance to contemporary art production? The graphic base of Martin’s practice sharpens its currency for a digital environment where the hyper-malleable image no longer conveys a photographic truth but rather an infinite reproducability. In this changed technological situation, meaning is carried as much through structure as content and Martin’s cinema predicts this move.

I have indicated that Lynsey Martin’s available cinema is shaped not only by film technology’s architecture but by political forces and events, cultural position and class in ways barely visible, but all the more coercive because of it. The following generations of moving image artists are working to make such implicit forces more clearly readable within their abstract films. I have previously outlined Australian artist Marcia Jane’s conceptual light performances and installations in relation to a Terra Nullius tradition that plagues Australian culture. [30] The internationally visible contemporary work of Aura Satz, Jodie Mack and Max Hattler also come to mind.

Aura Satz’s Between the Bullet and the Hole (2015, 10 minutes) animates a graphic rush of technical imagery of ballistic tests and early computer paraphernalia. She frames this with information about the predominantly female technicians who performed the calculations for these tests during the Second World War. Like Martin’s Leading Ladies, the invisible life and language of the technical class is laid bare, but through a feminist framework that is explicitly political and didactic.

Jodie Mack’s single frame animation of discarded consumer materials builds an abstracted palimpsest of movement reminiscent of the layering Martin achieves in Whitewash and sections of Light and Dark with single frame scratches and patterning of line. Mack sources domestic materials and fabric patterns familiar in the family home, locatable in an arts and crafts tradition, but through single frame sequencing, charged with a new kinetic energy. Her New Fancy Foils (2013, 12 minutes, 16mm, color, silent) animates discarded paper sample books into abstract dancing patterns. Like Martin’s Leading Ladies despite these visual gymnastics, the samples’ underlying materiality and its technical graphic and design base, shines through.

Perhaps the most productive juxtaposition is with the contemporary work of Max Hattler who has coined the term ‘Abstracted Heterotopia’ to describe his own digital practice, but in screened rather than scroll form. Within the digital there is no scroll, of course, but a data file. Martin has identified Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Piet Mondrian, Kasimer Malevich’s House Under Construction (1914) and El Lissitzky’s Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919) as influences in his teaching and moving image practice. Lissitzky’s painting especially manages a strong narrative through its graphics, a strategy clearly taken up in Hattler’s Collision (2005) and his kaleidoscopic Stop the Show (2013).

NOTES

[1] Lynsey Martin, “Notes and Notations” in Cantrills Filmnotes (eds. C&A Cantrill) Issue 16 (December 1973), p. 18.

[2] Lynsey Martin, “Lynsey Martin” in Cantrills Filmnotes (eds. C&A Cantrill) Issue 9 (August 1972), p. 15.

[3] Jim Knox, “On, Off, Into and Across the Record” in RealTime Arts Issue 83 (Feb-Mar 2008) p. 49. URL: http://www.realtimearts.net/article/issue83/8908

[4] Peter Wollen, “The Two Avant-Gardes” Studio International (November/December 1975) pp. 171–175.

[5] Lynsey Martin, Frames: The Casual and The Considered and Beyond (Melbourne, Self-Published Notebook, 2007-14), pp. 1-49.

[6] Sam Rohde, “Avant-garde” pp. 183-199 in The New Australian Cinema (ed. Scott Murray), (Melbourne: Nelson, 1980), p. 183.

[7] Ibid p. 205.

[8] Lynsey Martin Program Notes provided for screening Belgrade, Serbia. (Melbourne, Self-Published Notes 2013)

[9] Lynsey Martin, “Letter from Lynsey Martin” in Cantrills Filmnotes (eds. C&A Cantrill) Issue 23/24 (July 1976), p. 9, 33

[10] Lynsey Martin, Email Correspondence Thursday, 7 April 2016 10:21 PM

[11] Lynsey Martin, (Melbourne, Self-Published Notebook, 2007-14), p. 27.

[12] See Dirk de Bruyn, “Out of the Frying Pan, into the Fire: Cantrills Filmnotes as Prestige Machine” in In Fragments: On Fragmentation (ed. Greg de Cuir Jr.) (Belgrade, Serbia: Alternative Film & Video Research Forum, 2014)

[13] See Mihovil Pansini, “Antifilm-What is it?” in As Soon As I Open My Eyes I See A Film (ed. Ana Janevski) (Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art, 2010) pp. 225-231

[14] Lynsey Martin, Email Correspondence Sunday, 12 April 2015 5:06 PM

[15] Lynsey Martin, Email Correspondence Monday, 13 April 2015 7:32 PM

[16] Corinne and Arthur Cantrill, “How Do You Arrange a 14 Day Film Workshop” in Cantrills Filmnotes (eds. C&A Cantrill) Issue 9 (August 1972), p. 4.

[17] Lynsey Martin, “Short Films” in Cantrills Filmnotes (eds. C&A Cantrill) Issue 9 (August 1972), p. 6.

[18] Steven McIntyre & Dirk de Bruyn, “24 Tweets Per Second: A Dialogue on Jorge Lorenzo’s On the Road by Jack Kerouac” in Senses of Cinema Issue 68 (September 2013) URL: http://sensesofcinema.com/2013/feature-articles/24-tweets-per-second-a-dialogue-on-jorge-lorenzos-on-the-road-by-jack-kerouac/

[19] Lynsey Martin, “Notes and Notations” in Cantrills Filmnotes (eds. C&A Cantrill) Issue 16 (December 1973), p. 14

[20] Michael Brown, Michel Carnoy et al. White-Washing Race: The Myth of a Color-Blind Society (University of California Press, 2005)

[21] Lynsey Martin, “Notes and Notations” in Cantrills Filmnotes (eds. C&A Cantrill) Issue 16 (December 1973)

[22] See Barbara Pichler & Claudia Slanar, James Benning (Vienna: Filmmuseum Synema Publikationen, 2007)

[23] Jonathan Palomar, “Santiago Álvarez: The Revolutionary Filmmaker as a Materialist Historian”, in Found Footage Magazine Issue 1 (2015).

[24] Lynsey Martin (2015a) Notes for Abstract Cinema Screening. Melbourne International Animation Festival.

[25] Lynsey Martin, “Leading Ladies” in Cantrills Filmnotes (eds. C&A Cantrill) Issue 29/30 (February 1979) p. 32.

[26] Online Catalogue Notes (National Film and Sound Archive Non-Theatrical Lending Collection) URL: http://loans.nfsa.gov.au/htbin/wwform/076?T=0670076

[27] Michel Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1962) p. x.

[28] Dirk de Bruyn, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: The 2012 Alternative Film/Video Festival” Senses of Cinema, Issue 66 (2013) URL: http://sensesofcinema.com/2013/festival-reports/the-more-things-change-the-more-they-stay-the-same-the-2012-alternative-filmvideo-festival/

[29] Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias” pp. 22–27 trans. by Jay Miskowiec in Diacritics 16, no. 1 (Spring 1986), p. 26.

[30] See Dirk de Bruyn, “Blind Alleys, Blinding and Blinded Aliens: Mapping the Outer Limits of the Technical Image”, in Expanded Architecture: Avant-garde Film + Expanded Cinema + Architecture, Lee Stickells, & Sarah Breen Lovett (eds) pp. 44-50, (Berlin: Broken Dimanche Press, 2012).