[1]

Any Melbourne Cup race is a dramatic competition. In 1896, Newhaven was the favourite and, having streaked past the finishing post six lengths ahead of the other horses, was clearly the winner almost from the beginning. For the first time, motion-picture cameras captured the action on and off the course as Marius Sestier, a representative of the frères Lumiere, and Henry Walter Barnett, a highly-regarded Australian portrait photographer, were on the field with their Cinématographe Lumière.

But in addition to the race itself, their 58-second-long film of the milling crowd, The Lawn Near the Bandstand, reveals another heated competition, one which played out much less dramatically, and without such a clear winner: the rivalry between two separate companies vying to dominate the fledgling moving picture business in Australia. Sestier’s camera captured the anger of one of his rivals, Charles MacMahon, at the exact moment he realised a Frenchman had beaten his company at being the first to film the Melbourne Cup.

The Lawn Near the Bandstand was one of a series of films to be shot by Sestier and Barnett as they covered Derby Day on Saturday 31 October and then three days later on Tuesday 3 November, the Melbourne Cup. They captured moving images of the crowds, race day events and the main race. A selection of eleven films was released as the first program of locally produced films on 24 November 1896 in Sydney. This program was also the first film series of a sporting event. [2] Since it was produced within the first nine months of the first public Paris screening of the Cinématographe Lumière and was then seen around the world from February 1897, the program situates Australia at the forefront of the development of international cinema practice. It was no mean achievement and one by which local competitors were threatened.

The filming of the 1896 Melbourne Cup by necessity had to be well planned. On the previous Saturday, Sestier and Barnett attended Derby Day to survey the grounds and decide on vantage points. To capture the key events of the day would have meant that the pair had to be on the ball, their camera in place and ready to roll. Unquestionably, the race films – The Finish of the Hurdle Race and Finish of the Race, Lady Brassey Placing the Blue Ribbon on “Newhaven”, filmed on Derby Day, and The Arrival of H.E. Brassey – required precise timing to ensure the key action was captured. After all, it would not have been possible for the race to be run again simply for the benefit of the camera, or to ask Lord Brassey and his entire entourage to once again descend their carriages. Indeed, the latter film, which captures the entire vice regal party ambling towards their private enclosure, demonstrates impeccable timing. There are no edits, pauses or jumps. It is one continuous scene.

On the other hand, the crowd films – Arrival of the Train at Hill Platform, The Saddling Paddock, Weighing Out for the Cup, Near the Grandstand, Afternoon Tea Under the Awning, “Newhaven” His Trainer (W Hickenbotham), Jockey Gardiner, and The Lawn Near the Bandstand – are much less constrained by time. All of these films could have had multiple takes before Sestier and Barnett were happy with what they had captured. The crowd scenes provide fascinating perspectives of the day and the people, and also reveal the choices made by Sestier and Barnett over which films to include for screenings. For such films, the final selection was based on composition, celebrity and image quality.

Considering the possibility that The Lawn Near the Bandstand, like the other crowd films of the day, could have entailed several takes, suggests that Sestier and Barnett deliberately chose to include the close-up of their business rival Charles MacMahon. What a coup for Sestier and Barnett to be able to show the magnificence of the Cup crowd, have big name stars parade in front of the camera, provide Australia with its first program of local films, and to ridicule and embarrass a business rival all at the same time.

The film’s subtext of a business rival’s humiliation has only come to light in an attempt to identify the film’s long-forgotten celebrities through a frame-by-frame analysis. [3] Prior to this analysis, Charles MacMahon’s moment is easily overlooked as merely that of another person staring into the camera. However, Charles’ expression of annoyance and anger is atypical of the crowd’s general reaction of curiosity or amusement at this new contraption, this “scientific invention of the century”, the cinématographe.

Simultaneously, and just as easily overlooked, is the moment Marius Sestier is seen to walk out into the crowd, then turn and stare directly into the camera. He wears a light, summer suit tailor-made in Bombay, binoculars across his back and a straw boater on his head. At one point the two men are almost shoulder-to-shoulder but do not greet or acknowledge each other. However, they were soon to go head to head in a clash for domination of the Sydney motion picture exhibition market.

To place this rivalry within context and put it into sharper perspective, a brief examination of the contemporary Cinematographe business is required both in its global reach and its specific Australian context. French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière launched their Cinématographe Lumière to the public in Paris in February 1896. Although there were other moving-picture machines, theirs was the first of its kind, a machine which could project, capture and develop moving images. Its versatility and portability meant the frères Lumiere were the first to embrace the global distribution, exhibition and production of the projected moving image in country after country in rapid succession and synchronicity. They sent representatives, like Marius Sestier, on long voyages to show projected images as well as film new material, and the resulting films were then circulated. Sestier, for instance, visited Bombay and Australia. Of the nineteen or so films Sestier made, eight were incorporated into the first Lumière catalogue. These films were then first screened in Lyon at the Lumières’ own cinema on the rue de la Republique and then throughout Europe, certainly in Italy and Hungary, as well as in Mexico and Brazil. [4]

But within a few months of their early global dominance, the Cinématographe Lumière was confronted with competition from Britain, America and even from within France. When Sestier arrived in Australia, he advised the frères Lumi ère that there was much money to be made, but that there was competition. The brothers’ pragmatic reply: “…it is impossible to prevent”. [5] But they gave no advice on how to deal with competitors except to confirm that Sestier had exclusivity to the patented Cinématographe Lumière.

From the day that Marius Sestier and his wife Marie-Louise disembarked in Sydney on 16 September 1896, they quickly became aware they had arrived in a country where the word “cinematographe” was already synonymous with the apparatus, any apparatus, which projected moving images. Without exception, all exhibitors either called their machine a “Cinematographe” or it was named so by the press, even though none were actually operating the authentic Cinématographe Lumière. This was a very different scenario to the Sestiers’ experience in Bombay where they had had the market to themselves. But in Australia they continually had to contend with those who traded on the reputation of the patented Cinématographe Lumière. To counter this, they launched a campaign asserting its authority, authenticity and superiority, and disparaged all those who traded on the name Cinématographe.

Although the competition was increasing quickly, the Sestiers initially aimed their campaign at two competitors in particular – the magician Carl Hertz, who was operating in Sydney when the Sestiers arrived, and the MacMahon Brothers in Brisbane. [6] With its brighter, clearer and steadier image, the superiority of the Cinématographe Lumière was easily recognised by the public’s discriminating eye, as per Le Courrier Australien: [7]

« Nous en somme sortis émerveillés…Les tableaux reproduits par l’appareil Lumière sont dépourvus de ces mouvements saccadés et de ces lueurs crues, fatigant la vue que l’on constate avec les appareils imités du cinématographe de l’inventeur français. On suit facilement, grâce à lui, sans la moindre fatigue, toutes les scènes les plus variées. »

(Basically, we left delighted…The pictures reproduced by the Lumière machine are devoid of those jerking movements and crude flashes which tire the eye as seen with the imitators of the French cinématographe. One can follow easily, without the slightest fatigue, all the different scenes.)

But their campaign was successful to a point. The enormous public interest in the scientific invention of the century proved that all moving image exhibitions would make a profit regardless of its manufacturing provenance. It was an opinion echoed by The Bulletin in early October of that same year: “The Cinematographe seems likely to prove the very best show-speculation ever brought to Australia.” [8]

Of his two main competitors, the MacMahons would prove to be the more significant and persistent for Sestier. [9] The MacMahon Brothers – James (Jimmy), Joseph (Joe), Charles, and William (Willie) – were a well established theatrical management company. They had started in Bendigo on the Victorian goldfields in 1875 and had created a successful national and international enterprise encompassing lectures, drama, comedy, opera, variety and a roller skating rink. In the 1890s they broadened out into the world of Edison novelties and had brought to Australia the Phonographe in 1890, the Kinetoscope in 1894 with J. C. Williamson, and the Kinetophone and Phonoscope in early 1896. [10] With these novelties the MacMahons had enjoyed a monopoly and had come to expect this would continue. For them, there was no reason the Cinematographe would be an exception.

However, the frenzy of motion-picture inventions reaching Australia soon proved they could not have everything go their way. On 27 August 1896, the MacMahons held a private exhibition of a “kinetomatographe”, [11] a projection version of Edison’s Kinetoscope, at the Criterion Theatre in Sydney. Although they had declared it would be showing soon, they opted to open instead in Brisbane on 26 September. This may have been because they failed to secure a Sydney venue before Carl Hertz opened there. However, a more likely explanation could be that Brisbane, one of the MacMahons’ regular theatrical locations, had not yet been exposed to the projected moving image. An uninitiated Brisbane public was ready for exploitation. [12]

|

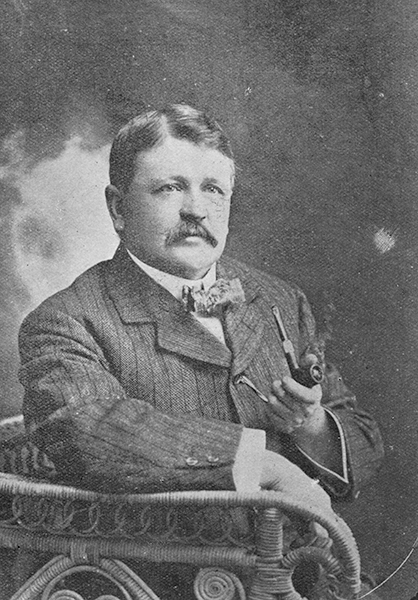

NFSA #6071 The Lawn Near the Bandstand (Sestier, Australia 1896), croppedframe enlargement. Front, from left: actress Emma Temple, photographer Henry Walter Barnett talking to actress Winifred Austin, next to her is Charles MacMahon staring directly into the cinématographe. Far left centre Marius Sestier, in white suit and a straw boater, stands and looks directly into the cinématographe. |

Charles MacMahon was already in Brisbane with the George Darrel Dramatic Company when his brother Joe arrived on 23 September to finalise requirements for the presentation. They had taken a shop in the Royal Arcade on Queen Street and set it up in the French style – that is, a venue dedicated to the continuous screening of films, a template developed by the frères Lumiere to which Brisbane audiences responded most favourably. Like Hertz, they advertised their Edison Kinetoscope as a “Cinematographe”. [13] Both Charles and Joe closed their shows on 10 October due to other engagements, which for Joe meant taking their “Cinematographe” to New Zealand on the steamer Anglian, leaving Sydney on 14 October. [14]

While Joe made his way to New Zealand, Charles headed back to Sydney to work with James. Even though their “Cinematographe” season in Brisbane was a sensation, the MacMahons were canny operators and would not be pleased at having missed the exploitation of Australia’s two largest audiences, Sydney and Melbourne, with a premiere of their new electrical novelty. To compete in these markets they would need to increase the novelty value of their presentation.

Meanwhile in Sydney, the Sestiers were fortunate to enjoy the patronage of J. C. Williamson of Williamson & Musgrove, at that time Australia’s largest theatrical management group dedicated to quality theatre. They had opened the Salon Lumière in a shop front at 237 Pitt Street on 28 September, closing a month later on 27 October. This venture was operated by the skilled and experienced hands of Charles Babbington Westmacott, an independent theatrical manager, and the highly regarded George L. Goodman, who was Williamson & Musgrove’s Sydney-based theatrical manager, a management team which ensured the smooth running of the business and the positioning of the Salon Lumière as the must-see event of the century.

Another important member of the team was Henry Walter Barnett, who soon received billing in the Salon’s advertisements and was the Sestiers’ key contact and driver in Australia for the next four months.

A tremendously successful season resulted. The daily box office receipts were high and audience queues often stretched across the street. More importantly though, Sestier, Barnett and their management closed the season by presenting the first film to be successfully produced and screened in Australia, Passengers leaving the ferry “Brighton” on a Sunday afternoon. Sestier and Barnett had consequently raised the bar and set a challenging precedent for all other exhibitors. As their season in Sydney came to a close, they announced their departure for Melbourne and revealed they would make a whole series of Australian films.

Although Sestier and Barnett did not disclose exactly what those Australian films were to be, as early as 3 October 1896 a call for the Melbourne Cup to be filmed had been published in The Bulletin. R. W. Paul’s recent films of the 1896 English Derby had drawn consistently huge crowds to Rickards’ Opera House in Melbourne and the Tivoli in Sydney, where they continued to be screened. It was this success that prompted Carl Hertz to claim that he was in the process of importing all the necessary equipment to make his own films, the first of which would be the Melbourne Cup. [15]

Up to this point in time, the MacMahons’ Edison equipment limited them to only projecting films, not making them. But now, they too, signaled their intention to begin production. In an Adelaide Register interview published on 19 October, James MacMahon, who had recently returned from Paris, stated that the he had brought a new French projecting machine, the Animatographe-Demenÿ, along with film negatives and filming equipment. [16] The MacMahons’ first venture into filmmaking, he claimed, would be the finish of the 1896 Melbourne Cup, a claim that was reiterated on 26 October in the Sydney Morning Herald.

That there should be such intense focus on the filming of the Melbourne Cup is not at all surprising. It was already recognised as an international event that drew visitors from abroad, and was covered by all national press and by much of the international press as well. The popularity of Paul’s films of the English Derby presaged that any similar film, especially a locally produced film, would do exceptionally well at the Australian box office. For Sestier, the Melbourne Cup also fit the bill when the Lumières advised Sestier to “choisiez mieux sujets” (“choose the best subjects”). [17] And given that he and Barnett had also raised the bar with Passengers leaving the ferry “Brighton” on a Sunday afternoon, the rivalry to produce such a film locally was fierce.

Sestier’s trip to Melbourne was required by his contract with Williamson & Musgrove. He was to appear with the Cinématographe Lumière in the Cup Week revival of their pantomime Djin Djin the Japanese Bogeyman. In Sydney the Sestiers had immersed themselves in the French community and had found an engineer and electrician Auguste Plane, who also travelled to Melbourne. [18] Plane’s familiarity with the Cinématographe Lumière covered not only the electricity supply; he was required to know all parts of its operation.

Barnett also made the trip to Melbourne, his hometown, and where a relatively new branch of his Falk photographic studio had opened. Amongst the employees at the Melbourne branch were Walter’s younger siblings, brother Charles and sister Phoebe, whose responsibilities included attention to business affairs and taking photographs. Although he had society contacts, Barnett also moved in artistic circles. At this very point, he was occupied with his good friend the artist Arthur Streeton, who was working towards an exhibition in Barnett’s Melbourne studio. [19]

Melbourne Cup week gave the city a carnival atmosphere, with venues catering to all manner and taste of entertainment. Amongst the dramas, comedies, circuses and pantomimes were four separate presentations of projected moving pictures. With the exception of the Vitascope screening at the Athenaeum, all advertised their equipment as a “Cinematographe”, although, in fact, none were Cinématographe Lumière. [20] If Sestier had been earlier frustrated with the misappropriation of the “Cinematographe” name by Hertz and the MacMahons, the proliferation in Melbourne of unauthorised “Cinématographes” would have increased his frustration levels.

Simultaneously, and which must have added insult to injury, his previous business partners, Westmacott and Goodman, advertised, within 24 hours of Sestier vacating the Salon Lumière at 237 Pitt Street, a new “Cinémathographe” to open on Saturday 31 October. There was no doubt that their venture, the Salon Cinématographe, intended to exploit the well-earned reputation of the Salon Lumiere. When Sestier and Barnett learned that Westmacott and Goodman were soon to be replaced by the MacMahons and their “rival French machine”, [21] it caused friction between the former business colleagues. Sestier obviously felt the need to separate the Salon Lumière from the Salon Cinématographe for he published in the Sydney papers “A Card” disassociating himself, as well as the superior and genuine Cinématographe Lumière, from this new venture.

The Lawn Near the Bandstand thus offers us a comment on this fraught situation. Marius Sestier deliberately walks into the crowd of race-goers, turns and stares directly into the Cinématographe Lumière. Unlike Barnett, who is also in the film, Sestier was unknown to Australian audiences and would have been familiar only to a select few, such as his ex-business partners, competitors, family and friends. His decision to deliberately put himself in this film has only one credible reason in this context. He was well aware that his competitors were blatantly exploiting the well-established reputation of the Cinématographe Lumière, and he knew that there had been two public claims to film the Melbourne Cup (the significance of these claims was enough to prompt him to keep the press cuttings in his scrapbook). But neither party – Hertz or the MacMahons – were that day present on the field with their cameras. Sestier’s appearance, then, asserts his victory in the race for the Melbourne Cup films and therefore his dominance of the Australian market through quality content and technical superiority. In other words his appearance is as if to say: ‘I am here and I’ve stolen your thunder!’ [22]

Sestier’s appearance however, inadvertently raises a question: if he is not behind the camera, then who was operating it?

One might immediately assume Barnett was behind the camera, especially since the press at the time often attributed the making of the films to him:

“M. Marius Sestier has been enabled thus to enrich his repertoire by the skill of M. H. Walker [sic] Barnett (“Falk”), who with complete success has secured a long series of views of the Melbourne Cup…”

“Mr Walter Barnett has been conducting experiments in the photography of the Melbourne Cup…”

“Mr H Walter Barnett (“Falk”) has taken film views of Newhaven’s race for the Cup…” [23]

The problem with this assumption, as will be discussed below, is that Barnett is seen working the crowd, and both men are seen in frame simultaneously. The next likely candidate would be Barnett’s brother Charles whose presence is confirmed in a series of letters in the film trade magazine Everyones in 1923-24:

The next picture show was given in November of the same year [1896] in the Criterion Theatre, Sydney … The star attraction was “Newhaven Winning the Melbourne Cup.” … The photographers were Harry and Charlie Bennett [sic], who had a very fine photography establishment in George Street, where they transacted business under the trade name of “Falk”. [24]

However, Charles, like Sestier wears a light coloured suit and straw boater, and he too is seen on screen. The most plausible assumption is that Auguste Plane was the person responsible for operating the camera and capturing a parade of well-known identities, among them Sestier’s rival.

The Melbourne Cup series of eleven films was undoubtedly a coup that put pressure on Sestier’s competitors. Strategically, the films engaged audiences on a variety of levels: the excitement of racing, the vitality of the horses, the splendor of the venue and, importantly, the prestige of famous faces seen throughout the series.

But capturing the images of well-known faces was not a chance occurrence. Rather it was by design, an orchestrated commercial strategy. In the Arrival of H. E. Brassey and Suite can be seen celebrity in all of its regalia, but The Lawn Near the Bandstand is not simply about the events of the day. It focuses almost entirely on celebrities, as Barnett can be seen guiding high-profile international theatrical stars from the Brough Comedy Company. The famous actor Mr George Titheradge and company director and star Mrs Elizabeth Brough are brought before the camera. A moment or two later Barnett is engaged in conversation with more of the company’s stars – Miss Lily Titheradge, daughter of George, who is soon joined by Miss Emma Temple. Barnett then walks towards the Cinématographe Lumière with Sydney socialite Miss Winifred Austin, a new starlet of the Brough Comedy Company. [25]

|

As a photographer of the rich, famous and important, Barnett was very well connected and at ease with those whom he photographed. His successful business was founded upon the vanity of high society, and sales turnover of his cabinet card portraits gave him an understanding of the currency of celebrity. When Walter Barnett guided the famous past the camera, he knew the resulting footage would appeal to press and audiences around Australia, Britain and Europe. And he was not wrong:

Well known figures pass and re-pass in living semblance to their very selves… [26]

The audience found a vast fund of amusement in picking out well-known faces as they occurred in the throngs, and indeed, quite a society column of “those present” might be written if space permitted. [27]

Barnett’s careful choreography is augmented by other known identities that are simply passing by, or have been drawn towards the camera. Such is the illustrator and artist Percy Frederick Seaton Spence (Percy F. S. Spence). Spence had sketched Sestier and Barnett three days earlier on Derby Day and his sketches – titled “For Posterity” were later published in The Bulletin. Also walking into the scene is circus owner Dan Fitzgerald and his manager Herr van den Mehden, who first peers around into the camera from screen left. Then both men move into the background to turn and watch the action.

But no amount of planning by Barnett could foresee the somewhat ironic capture of their competitor Charles MacMahon. MacMahon is with his financial backer, John Hunter, and the artist Percy Spence. All are obscured by the crowd and unaware that they were close to the Cinématographe Lumière until the crowd parts. MacMahon notices the camera, alerts his companions, and they move towards it. As they navigate the crowd, they come shoulder to shoulder with Marius Sestier who, with a tilt of his head, recognises Spence but the two do not greet one another. MacMahon and Hunter are ignored. But, as Sestier moves away the other three move closer to the camera and we clearly discern the expressions on their faces. Spence smiles, waves and obviously recognises the machine and its operator. Hunter is unhappy, almost sneering, perhaps wondering if he has backed the wrong operation. Charles MacMahon is angry and annoyed. He makes a direct path to the Cinématographe Lumière, stops momentarily, stares straight into the lens, says something then swiftly walks away.

As noted earlier MacMahon’s expression is atypical of the crowd’s reaction where the majority of passers-by are bemused or puzzled. Some would have recognised the apparatus and expected to see themselves on the big screen. But MacMahon had an obvious reason to be annoyed at the presence of the Cinématographe Lumière. His brother James MacMahon had blown their trumpet in Adelaide and Sydney as owners of the best, most advanced, and most highly perfected moving image apparatus, the Animatographe-Demenÿ. On top of it all, James had declared publicly that they would film the finish of the Melbourne Cup race.

The MacMahons had not yet opened in Sydney as intended at the former premises of the Salon Lumiere. It would be within reason for them to delay the opening in order to attend the Melbourne Cup to film the main race of the day. However, James, the only person who knew how to install and use the Animatographe-Demenÿ, was engaged in an unexpectedly complex and dangerous installation process that included a problematic modification of the venue and was in no position to comply with his promise. Moreover, had the MacMahons been on the field with their camera, they would most certainly have been noticed by the press, as had the Cinématographe Lumière:

But the Cup of 1896 boasted, at least, one novel feature. The photographer, of course, we have always with us, but this year the cinematographe, for the first time, played its part on an Australian course, and by the Lumière principle a series of views were taken, which will carry to London, Paris and St. Petersburg an actual presentment, not only of the Cup meeting, but of the most wonderful Cup race ever run over the classic course… [28]

It’s understandable that their failure to be the first to make a film of the Melbourne Cup, or any kind of local film, would cause Charles anger. There was, however, much more riding on this.

The MacMahons were in a financial hole caused by their disastrous 1891 tour of American boxer-turned-actor “Gentleman” Jim L. Sullivan. The MacMahons had miscalculated Sullivan’s talents as an actor and his novelty worth was not enough to draw audiences. Their finances suffered substantially and their company fell into insolvency. In 1896 the continuing economic depression and a severe and lengthy drought had kept audiences away, and those who did attend expected the status quo of high quality shows to continue. The MacMahons were hard pressed to regain their financial position.

One can add to this their litigious nature. Since 1880, they had been engaged in some ten or so legal suits, which compounded their difficulties until in 1895 when their insolvency was discharged. [29] Overall, the MacMahons were still in dire financial straits. With the financial backing of boot and shoe manufacturing magnate John Hunter, a relationship which would later see them in bankruptcy court, [30] they had relied on the “Cinématographe” to pull them out of the red.

But even before the return of James from Europe in October, they had lost their advantage. “Cinématographes” continued to multiply, popping up all over Australia. (Even Joe’s arrival in New Zealand was secondary to Charles Godfrey and his Edison Kinematographe, even though, to counter Godfrey’s dominance, Joe began his tour in towns still to be exposed to moving pictures.) Ironically, this was the same situation that Marius Sestier faced when he arrived in Australia, an explosion of competitors, which, in this case, had the potential to ruin the MacMahons’ plans to regain financial security and advance their business.

Thus, on Tuesday 3 November at the 1896 Melbourne Cup, Charles MacMahon, of all the people caught on film that day, would understand only too well that his staring into the lens would result in his face being seen larger-than-life by audiences around the country and overseas. Yet he grimaces and says something to camera before disappearing from the screen. Alas, Charles had no other option for he would have immediately grasped his company’s predicament: the MacMahons had been pipped at the post in Australia’s cinematographe business stakes. It was the last thing they needed.

|

Postscript

The MacMahons’ Salon Cinématographe opened in 237 Pitt Street, Sydney, on Saturday 7 November, filling the gap left by Sestier and Barnett. James and Charles ran the business jointly; the latter took care of finances while James personally operated the Animategraphe-Demenÿ. Within the first week they claimed 10,000 people had visited the Salon Cinématographe [31] and for seventeen days the MacMahons held the Sydney market and were firmly established by the time Sestier and Barnett opened in Sydney on 24 November with the Melbourne Cup films.

The Salon Cinématographe operated with a continuous rotation of programs, the same manner as had the Salon Lumière. The MacMahons’ repertoire was strong and, apart from a hiccup or two on opening day, things were going well. Over the weeks one of their films developed a cult following, “La Loie Fuller” – the famous skirt dancer who used colour limelight effects on her twirling skirts was replicated on film in colour:

The demand for the skirt dancer is practically unlimited…his [MacMahon’s] audiences fall down and worship the dancing, empty headed charmer in the flying muslins, and if an attempt is made to withdraw her even once they threaten to rise en masse and boot the whole machine into the middle of the Age of Consent or something. [32]

But the twirling skirts were not enough to stave off the attraction of the first locally produced film series, Sestier and Barnett’s Melbourne Cup Carnival 1896, which drew consistently high audience numbers to the Criterion Theatre. The Melbourne magazine Table Talk reported that both businesses were doing exceptionally well, but that Sestier and Barnett were ahead of the MacMahons in both audience and box office receipts. [33]

However, it would be the MacMahons’ own lack of attention to detail regarding financial matters which would see the Salon Cinématographe close in November 1897. Unlike Sestier who circulated around the country at his own discretion, the MacMahons allowed market forces to take their toll. In September 1897 James and Charles took on a lease for the Lyceum Theatre. They had been watching the bottom drop out of their Salon Cinématographe for some months as newer machines with greater attractions arrived on the scene. They ran the two businesses together briefly, and even offered a buy-one-get-one-free ticket option for the Salon Cinématographe. But cheaper ticket prices could not draw crowds and by 5 December the Salon Cinématographe was no longer in operation. The rooms at 237 Pitt Street had been taken over by a betting agency.

The situation worsened for the MacMahons when in early 1899 James faced bankruptcy court. During the hearings it came out that all money earned by the Salon Cinématographe went straight into the pockets of their backer, John Hunter. Hunter, who kept all of the accounts, allowed the MacMahons to draw a weekly salary of £13 each along with a promise of half the profits. In court the MacMahons claimed that 200,000 people had paid 1 shilling each to visit the Salon Cinématographe between its opening in November 1896 and closure in November 1897. If such was the case a potential £10,000 was paid into the box office. However, despite their hard work and dedication the MacMahons reaped none it.

Endnotes

[1] 7 November 1896, ‘Theatrical’ The Arrow, p. 4

[2] According to La Production Cinématographique des Frères Lumière (Aubert et Seguin, BIFI, 1995) other sports films were made around the world but were one-off scenes. The 1896 Melbourne Cup films were the first to cover the proceedings of a whole day at a sports event and in some respects create a narrative. When the films were sent back to Lyon a selection of eight films were incorporated into the Lumières’ first catalogue from which all operators could select. The film which had the most appeal for exhibitors was not a racing scene but Arrival of a Train, Hill Platform which was removed from the Cup films and included in the Villes et Paysages (Towns and Countryside) genre. It appears that the crush of people emerging from the train, something not generally seen in other train films, caused much delight for audiences. Sestier and Barnett’s film became a great hit and was one of the films selected to be screened backwards.

[3] This new interpretation of The Lawn Near the Bandstand sheds more light on the film Patineur Grotesque, which does not appear to have been screened in Australia. I have previously proposed in ‘Patineur Grotesque: Marius Sestier and the Lumière Cinématographe in Australia, September-November 1896’, in Screening the Past Issue 28, 2010, (http://www.screeningthepast.com/2015/01/patineur-grotesque-marius-sestier-and-the-lumiere-cinematographe-in-australia-september-november-1896/) that the reason it wasn’t screened was because it was potentially libellous towards Harry Rickards. However, with this relationship with the MacMahons and the fact that they had run a roller skating rink it seems more likely that the film was aimed at them. The MacMahons were known to be litigious, (see endnote 29), and having sued for libel previously it is not beyond reasonable doubt that they would have done so if Patineur Grotesque had screened in Australia.

[4] The eight films selected were divided into two genres. The first genre was Vie Quotidienne: Distractions which included six of the 1896 Melbourne Cup films – La Foule (The Lawn near the Bandstand), Arrivée du Gouverneur (The Arrival of H E Brassey and suite), Enceinte du Pesage (The Saddling Paddock), Sortie des Chevaux (Weighing out for the Cup), La Course (The Cup Race) and Présentation du Vainqueur (Newhaven, his trainer, W. Hickenbotham and the jockey Gardiner). The second genre was Villes et Paysages which included Patineur Grotesque and a film from the 1896 Melbourne Cup series Arrivée d’un Train a Melbourne (Arrival of the Train, Hill Platform). This film was highly lauded as one of the best train films produced at that time.

[5] Sestier Tournée, Marius Sestier Collection, p. [8], National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra.

[6] Respectively a Robert W. Paul Theatrographe and an Edison Kinetoscope, The Theatrographe was a British adaption of Edison’s Kinetoscope.

[7] Nouvelles de la Semaine: Cinématographe. 3 Octobre 1896, Le Courier Australien

[8] 10 October 1896, The Bulletin

[9] Jackson, Sally. ‘Patineur Grotesque: Marius Sestier and the Lumière Cinématographe in Australia, September-November 1896’. Screening the Past Issue 28, 2010. The rivalry with Hertz is discussed. http://www.screeningthepast.com/2015/01/patineur-grotesque-marius-sestier-and-the-lumiere-cinematographe-in-australia-september-november-1896/

[10] For a more detailed and comprehensive discussion of the introduction by the MacMahons of the various machines see Long, Chris. ‘Australia’s First Film: Facts and Fables. Part One: The Kinetoscope in Australia’. Cinema Papers, January 1993, no 91, pp. 36-42.

[11] Sestier Scrapbook [2], Marius Sestier Collection, p. [2], National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. The first page of this scrapbook has three clippings about the MacMahons and their introduction of a “cinematographe” (8 August 1896 The Bulletin); a “kinetomatograph” (28 August 1896, Sydney Morning Herald and 12 September 1896 The Bulletin).

[12] Because Hertz’s Theatrograph and the MacMahons’ Edison Kinetoscope could both screen the same films it is possible there would have been programme duplication, something to be avoided when attempting to dominate a new market.

[13] 25 September 1896, Brisbane Courier, p. 2 ; The template for a screening is based on the frères Lumiere’s first screenings in Paris and Lyon then replicated by their representatives wherever possible: venue should be a cafe (Paris) or shop front (Lyon), run short 30 minute or less sessions continuously throughout the day and evening; rotate a programme of films. This template was copied by other moving image exhibitors and forms the basis for the development of cinema exhibition. It may have been inspired by Edison’s Kinetoscope parlours which operated continuously.

[14] 15 October 1896, Evening News p. 4; 20 October 1896, The New Zealand Herald, p. 4. It is interesting to note that a Margery [sic] is also on the Anglian. This is quite likely F. Marjory who operated the lantern for the MacMahons in Brisbane.

[15] 12 October 1896, “Amusements” Sydney Morning Herald p. 8.

[16] Exactly which machine the Animatographe-Demenÿ was is a matter for debate. MacMahon said that when he purchased it from the manufacturer in Paris it had not yet been presented to the public. Given the time frame of when he was there then the Animatographe-Demenÿ was most likely the new Chronophotographe, which used 58mm perforated film and was manufactured by Demenÿ-Gaumont. The Chronophotographe-Demenÿ was distinctive by its ability to project backwards. MacMahon’s repertoire of films match those produced for this machine including L’Avenue de L’Opera, which was screened backwards.

[17] Sestier Tournée. Marius Sestier Collection, p. [9], National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra.

[18] Sestier Tournée. Marius Sestier Collection, p. [12], National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. Auguste Plane, a Frenchman from New Caledonia, was a friend of Georges Boivin with whose family the Sestiers were staying in Sydney.

[19] Letter to Henry Walter Barnett from Arthur Streeton. MLMSS 285.

[20] The four other exhibitors were: 1. At 266 Collins Street on “The Block” the Cinématographe Perfectionnèe had opened on Monday 26 October. It was operated by the Frenchmen Albert J Perier and Gustave Neymark who were bankrolled by photographic supplies company Baker and Rouse. 2. Perier and Neymark would also present their machine in a prelude at the Theatre Royal where Perier’s good friend George Rignold was performing Shakespeare’s Henry V. 3. At Harry Rickards’ Opera House was a new R.W. Paul, supplied and operated by William Charles Baxter a circus and fairground equipment importer/supplier 4. At the Athenaeum was Edison’s Vitascope, presented by George “Tatt” Adams and was possibly the machine, intended to be presented at his Palace of Varieties that was due to open in Sydney before Christmas. The Vitascope would have been brought by Adams’ business partner theatrical impresario Arthur Garner when he returned to Australia in October on the Arcadia (with James MacMahon).

[21] 31 October 1896, ‘Dramatic Notes’ Sydney Mail, p. 926.

[22] Scrapbook [2], Marius Sestier Collection, p. [18], [25] National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra.

[23] 25 November 1896, ‘Amusements: The Lumiere Cinematographe’, Sydney Morning Herald, p. 8; 7 November 1896, Sydney Mail, p. 978; 24 November 1896, ‘The Lumiere Cinematographe’. The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 6.

[24] ‘Tom Howe Talks of Old Times’. Everyones, 12 December 1923 p. 26. This two column reminiscence by Howe (who was an employee of the Criterion Theatre in the 1890s) inspired a series of letters between Howe, Ted Breen and Franklyn Barrett. In this article and series of letters there is much confusion of time lines and events. However, in a follow up letter in the next issue, on 19 December 1923, Howe corrects Bennet to Barnett.

[25] For more information about some of the famous people featured in the 1896 Melbourne Cup films please go to: http://nfsa.gov.au/collection/film/marius-sestier-collection/spotted-1896-melbourne-cup-carnival/

[26] 25 November 1896, ‘Footlight Flashes: Lumiere Cinematographe’, The Referee, p. 7.

[27] ‘Amusements: Lumiere Cinematographe: Australian Scenes’. 25 November 1896, Daily Telegraph.

[28] 4 November 1896, ‘Cup Day An Enormous Attendance. The Favourite Wins. Another Runaway Victory. Extraordinary Enthusiasm’ The Argus, p. 5.

[29] Some of the law suits involving the MacMahon brothers up to 1896: 4 March 1880, The Argus, p. 3; 4 March 1880 – 7 May 1880, Bendigo Advertiser: Charles and Joseph involved in a scuffle which kills a man. Both brothers found not guilty; 24 July 1883, Bendigo Advertiser, p. 3: William and Joseph MacMahon charge a man with unlawful assault after refusal to allow them to book the theatre; 8 May 1885, The Mercury, p. 2: Alleged breach of contract by an employee against the MacMahons; 4 August 1888, The Morning Bulletin, p. 6: Joseph MacMahon charges an employee with assault; 9 August 1889, Evening News, p. 4: James MacMahon brings a writ against a principal performer for £3000 damages for assault; 8 March 1892, The Argus, p. 7: James and Charles are being sued by a supplier for failure to pay hire and performance fees; 16 March 1892, The Referee, p. 7: Charles and James MacMahon are suing the newspaper the Sunday Times for libel; 21 August 1893, Bendigo Advertiser, p. 2: William MacMahon sues business partner over breach of contract; 6 March 1895, New South Wales. J MacMahon’s Insolvency. The Brisbane Courier, p. 5. Concerns the discharge of insolvency.

[30] A Theatrical Manager’s Bankruptcy. 14 December 1899, Evening News (Syd); SRNSW: NRS 13655, [8/13740], Reading James’ depositions in his bankruptcy file he clearly identifies his brother Charles and John Hunter as the people in charge of finances. He points out that the bottom fell out of the cinematographe business while he was ill and overseas. In effect, he blamed his brother Charles for the financial straits he found himself in.

[31] The Cinematographe, 9 Nov 1896 Sydney Morning Herald p. 3; “Amusements” 14 Nov 1896 Sydney Morning Herald p. 2. In this advertisement the MacMahons claim 10,000 people have been to the Salon Cinematographe in a week of operation (6 days) that would be around 1666 people per day.

[32] Sundry Shows, 5 December 1896, The Bulletin, p. 8

[33] On and Off the Stage. 11 Dec 1896, Table Talk, p. 18.Table Talk does point out that the MacMahons would have lower overheads as opposed to Sestier and Barnett who leased the exclusive and expensive Criterion Theatre, so in terms of net profit the MacMahons would have been ahead.