Click here to view Knocknagow (1918)

Knocknagow (1918) has a special significance for followers of sport in Ireland.[1] Most immediately, it contains one of the earliest surviving depictions of hurling on film—and hurling’s earliest depiction in a fiction film—in the scene where Mat “The Thrasher” Donovan leads his team to victory amid cries of “Up Tipperary!” (Clip 1). The hurling match is followed by a highlight of both the film and the novel on which it is based: the famous hammer-throwing contest between Mat and Captain French, a local landowner’s son and undefeated champion (Clip 2). The film even includes real footage of a hare coursing event, a bloodsport akin to fox-hunting with strong roots in County Tipperary (Clip 3).

Clip 1.

Clip 2.

Clip 3.

Knocknagow’s sporting scenes, which make some effort to capture the form and style of these sports as played in the mid-nineteenth century, are crucial to how we understand the film as a historical document. Not only do they underscore the importance of sport for national identity, masculinity, and class in early-twentieth-century Ireland, they reveal the international focus of its followers, particularly through the involvement of Irish-born athletes at the Olympic Games. What is more, the film’s representation of hurling and hammer-throwing reflects the strong connections that existed between sport and early film at this time, internationally as well as in Ireland. Sport played a key role in the development and popularization of both nationalism and Irish film, and the inclusion of scenes of hurling and hammer-throwing would thus have had considerable political resonances for Knocknagow’s first audiences.

Sport and nationalism

Knocknagow’s sporting sequences may at first appear to provide viewers with a nostalgic and somewhat curious distraction from the narrative’s focus on romantic relationships and the corrupt machinations of the land-agent Pender. They are unlikely to be seen as part of the film’s efforts to accentuate the political resonances of the source text (see Rockett). Yet cultural activities such as sport are crucial determinants in the formation of national identity. For members of a nation-state, notes Ernest Gellner, “culture is now the necessary shared medium” (Gellner, 37–8). During the course of the nineteenth century, organized sport and, later, moving pictures played a large role in consolidating such collective identities—“imagined communities,” in Benedict Anderson’s oft-quoted formulation—even as these national identities themselves became increasingly important. Indeed, in emphasizing the banality of nationalism as a “natural” and often unnoticed part of everyday life, Michael Billig has argued that modern sport has a social and political significance that “extend[s] through the media beyond the player and the spectator” (Billig, 120) by providing luminous moments of national engagement and national heroes whom citizens can emulate and adore.

In Ireland, the emergence and consolidation of Irish nationalism, and the establishment of the independent Irish state, were both inextricably linked with sport, in particular the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), a body responsible for promoting and regulating Gaelic games and still the country’s largest sporting organization. Despite the efforts of GAA leaders to prevent the organization from being politicized, the emergence of many of the leading figures (and still more of the active volunteers) within Republicanism in the years leading up to and including the war of independence (1919–1921) from the ranks of the GAA affirmed that association’s nationalist credentials. Although it was to evolve into a promoter primarily of the Gaelic games of hurling and Gaelic football, in its formative years the GAA, as its title suggests, sought to foster Irish participation in a broad range of athletic pursuits, notably the hammer-throw.

The depiction of sport in Knocknagow, whose Dublin premiere on 22 April 1918 fell on the second anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, therefore had a political resonance for Irish film audiences. This significance was further enhanced by the fact that the film—unlike the novel, whose precise historical setting is unclear, albeit often presumed to be the 1850s (Rockett, 19)—is unambiguously set in 1848 during the Famine and in the year of the Young Ireland Rising.[2] Upon the film’s release, contemporary commentators remarked on its political reverberations, with the Bioscope noting that it was “dangerously tinged with political feeling” (16 October, 1919, 58). The inclusion of hurling and the hammer-throw no doubt added to these “political feelings”. Leading Republicans such as Michael Collins were closely associated with the GAA, and since 1916 the British government had imprisoned many members of the GAA, including its president, James Nowlan (Cronin, 87). Furthermore, there was a powerful symbolism in the use of hurley sticks as substitutes for rifles by Republican volunteers during training and drilling sessions throughout the 1910s.

Sport in Early Film

In part, the inclusion of sporting sequences in Knocknagow reflects the popularity, in Ireland as elsewhere, of cinematic depictions of sport. In the 1870s, Eadweard Muybridge’s pioneering attempts to capture motion using photography were focused on sport and included images of members of San Francisco’s Olympic Athletic Club engaged in various “athletic pursuits from boxing to jumping” (Clegg, 137). Sport was also a popular subject in early Kinetoscope films produced by the Edison Company, such as Men Boxing (USA 1891), Wrestling Match (USA 1894), and The Hornbacker-Murphy Fight (USA 1894). After the arrival of projected films in 1895, sport continued to feature regularly as a crucial element of what Tom Gunning has termed the “cinema of attractions”.

As Luke McKernan observes, early cinematic depictions of sport “represented the changeover from film as a medium of scientific study to a medium of entertainment” (McKernan, 109). While novelty may have attracted the first viewers of moving images, sport—above all, boxing in the United States—emerged as an important subject of cinema during its first decade, helping to ensure the medium’s continued popularity. McKernan identifies in the early boxing films in particular “the very birth of American cinema realism and drama, newsfilm and fakery, commercialism, populism, professionalism, two protagonists battling within the perfect staging, the ring” (McKernan, 110). Indeed, boxing was the subject of the first feature-length films, and boxing films were the first to use actors and the first to be given commercial screenings.

Irish Americans figured prominently in “prize fight films”, as these highly popular productions came to be known during the first two decades of film. Irish and Irish-American boxers (and athletes more generally) enjoyed considerable success in this period, and some of the most successful early films featured pugilists from an Irish background. An Irish-American, the reigning world champion “Gentleman” Jim Corbett was one of the stars of The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight (USA 1897, dir. Enoch J. Rector), which some commentators regard as the first feature-length production and first box-office smash in cinema history (Streible, 73). The fight had been held on 17 March 1897, the choice of St. Patrick’s Day reflecting the champion’s Irish ethnicity as well as boxing’s popularity among the large Irish-American community in the United States (Streible, 52).

The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight was screened in Ireland, where, like subsequent fight films, it was received enthusiastically by Irish audiences. These screenings were not without controversy, however, and Kevin Rockett notes that the first major debate over censoring the cinema in Ireland concerned the screening of a world heavyweight bout in 1910 between James J. Jeffries and Jack Johnson, an African-American. Prominent Irish political and religious figures sought to ban the film lest its interracial subject cause offence to visitors from America, where the film had prompted considerable protests from white Americans and had been banned in several cities (Rockett, 31–5).

Unsurprisingly, Irish sport, including Gaelic games, featured prominently in early Irish film. The earliest record of the filming of a Gaelic game—a clip that unfortunately has not survived—is of a Cullen’s Challenge Cup hurling game played between “Rovers” and “Grocers” at Jones Road (now Croke Park) on 8 of December 1901. Made by the Irish Animated Photo Company, an early Irish actualities company, the film was shown three days later as part of a “Grand Gaelic Night” at Dublin’s Rotunda (see Monks). Gaelic games and other Irish sporting events continued to feature in Irish-made actualities and newsreels, including the Irish Animated Picture Company and Irish Events (1917–1920), as well as in newsreels produced by foreign companies such as Pathé, Movietone, and Gaumont British. These films enjoyed a significant following among Irish audiences throughout the silent period. On at least one occasion, in 1913, an Irish Animated Picture Company film of a Gaelic game played between Kerry and Louth was sufficiently popular to take “the place of a feature” in a screening in Kerry, where it was accompanied by a supporting programme of films and variety acts (Condon, 166).[3] While Knocknagow represents one of the earliest instances of sport in an Irish fiction film, sport was thus already an established part of film culture in 1918, both in Ireland and internationally.

Sport and masculinity in Knocknagow

The Film Company of Ireland had ample material to draw on when choosing which sports to depict in their adaptation of Charles Kickham’s novel. Indeed, reading Knocknagow; or, The Homes of Tipperary (1873), one is struck by the great number of recreational activities mentioned. Although many of these would today be considered as sports, sport was viewed quite differently in the mid-nineteenth century—whether the 1850s, when the book is likely set, or the 1870s, when it was written—when the codification of sport had only begun in Ireland.

As well as hurling and “throwing the sledge” (reinterpreted in the film as “the throwing of the hammer” [Intertitle 61]), the other “sports” mentioned in the novel include: swimming (Kickham, 45, 354); fishing (341, 489, 490); equestrianism (446); horse-racing (298, 446, 535); and boxing (83). Several references to greyhounds (Kickham, 131, 134, 459) suggest that hare coursing was a popular pursuit in Tipperary at this time. The novel also features “card-playin’” (Kickham, 440), local games such as pitch-and-toss (440), and what appear to be courting games and children’s games—the “high-gates,” “hell-and-heaven,” and “thread-the-needle” (441)—which occupy the crowd as they await the outcome of the hurling match and the sledge-throwing competition. In addition, Kickham mentions the seasonal St. Stephen’s Day “sport” of “hunting the wren” and “trick-o’-the-loop” (Kickham, 20–1, 529, 457), a guessing and gambling game popular at fairs (Synge, 78). Given the ubiquity of sports and pastimes in Kickham’s novel, it is not surprising that they also feature prominently in the film adaptation.

The inclusion of sport in the film adaptation thus reflects the popularity of sport in early film and its prominence in Kickham’s rendering of Tipperary life. Even so, the sporting sequences in Knocknagow (novel and film) play a crucial part in foregrounding the physical prowess and masculinity of Mat Donovan, qualities which drew, in turn, on the association between sport and masculinity being promoted by the GAA. The founding of the GAA in 1884 reflected concerns at the decline of native sports but also the perceived emasculation of Irish men. Writing to Michael Cusack to accept an invitation to become the GAA’s first patron, Archbishop Thomas Croke of Cashel lamented the “effeminate follies”—a reference to non-Irish sports and other “habits” imported from Britain—that he viewed as detrimental to Irish character (Croke).[4] Cusack himself drew a clear connection between hurling and masculinity, and, conversely, the “effeminate” sport of soccer, by arguing that “as the courage and honesty and spirit of manhood grow, the hurling steadily advances on the domains of football [soccer]”.[5] Significantly, the GAA concerned itself exclusively with men’s sports, and, indeed, did not admit women as members; camogie, the female version of hurling, was devised by female members of the Gaelic League (de Búrca, 93). Indeed, as Patrick F. McDevitt notes, “the efforts of these nationalistic women who took to the playing fields with camans in hand were not warmly received by the sporting community, and were largely ignored by the press and the GAA” (McDevitt, 273).

In Kickham’s novel, sport plays a central role in affirming Mat Donovan’s masculinity, physical prowess, and heroic stature, tropes that are similarly foregrounded in the FCOI’s adaptation. Variously described as “a magnificent specimen of the Irish peasant” (Kickham, 18), and the “hero of the district” (351), Mat achieves this status despite being “only a poor labourer” (352). Indeed, so important is his esteem to the community that fears are expressed by Mat’s neighbours about the standing of their village if he performs badly in the sledge-throwing contest. After Mat falls from a hayrick, Phil Lahy remarks:

“But what I’m afraid uv is that this fall may come against him in throwing the sledge with the captain. I’ll advise Mat not to venture. ’Tis too serious a matter. And—and,” added Phil Lahy, in a dignified way, “a man should not forget his duty to the public. That’s Mat’s weak point. He can’t be got to see that he’s a public character. The people at large are concerned. The credit of Knocknagow is at stake. So I must explain this to Mat. The captain, too, though a good fellow, is an aristocrat. That fact cannot be lost sight of. So I must explain matters to Mat. An’ if he’s not in condition, he’s bound to decline throwing the sledge with Captain French on the present occasion.” (Kickham, 365)

Sledge-throwing and hurling may be the most conspicuous examples of this process of heroization but Kickham’s novel also describes Mat as making “the name of Knocknagow famous” by being “such a hero with the people as the best hurler and stone-thrower” (Kickham, 283). Stone-throwing was a sport played in parts of rural Ireland in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and at the 1906 Intercalated Olympic Games in Athens the silver medal in the “Stone Throw” event was won by Martin Sheridan, an Irish-born American athlete.[6] Although not specifically mentioned in the film version of Knocknagow, stone-throwing clearly informs the novel’s celebration of Irish physical prowess as an index of national superiority.[7] (Mat’s infant son is approvingly described as a potential “stone-thrower” (Kickham, 609, 618].) In the film, intertitles repeatedly underscore Mat’s strength as an athlete and pugilist, “the finest lad in the county” with “a heart as stout as his arm” (Intertitle 10) and “worth twenty such men as this Dragoon” (Intertitle 107)—the British rival for Bessie Morris’s affections whom Mat gives a thorough “punishing” (Intertitle 114) (see fig. 1) . From the opening scene in which he ploughs a field to his fearless confrontations with the corrupt land-agent, Mat’s masculine physicality and moral fibre are repeatedly affirmed in a way that is clearly intended to stand as the counterpart of his mastery of hurling and, in particular, hammer-throwing.

Sport and Social Class

The choice of sports featured in Knocknagow (1918) is also central to the film’s representation of social class. In the novel, the men on each team in the hurling game are divided not just by a river but by social class: Mat’s team are “labouring men” and their opponents “farmers’ sons” (Kickham, 389). Although this division is not immediately apparent in the film, from his first appearance behind a plough Mat is clearly marked as a farm labourer, and the similar dress of the other hurling players suggests their membership of the same class. The status of hurlers was significant, since one of the GAA’s central concerns had always been to make athletics accessible to all social classes at a time when organized sport in Ireland was effectively reserved for the upper classes. As sports historians have noted, Cusack founded the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) as a check to the British Amateur Athletic Association’s expansion into Ireland:

Cusack was . . . irked that officially recognised athletics meetings were held on Saturdays, yet the traditional day for sport in rural Ireland was Sunday, and that the rules of the British AAA narrowed the range of athletes who could compete. This was sport not for the “amateur”, but for the “gentleman amateur”. In general, Cusack abhorred the increasing tendency of certain sporting organisations in Victorian Britain to move towards elitism and to seek to preserve their events for people from a certain class. (Cronin et al., 19)

Indeed, sport is one of the clearest indicators of social class in both the book and film versions of Knocknagow. In the novel, the term sport is primarily associated with the upper and upper-middle classes, while the peasantry engage principally in “games”. The word “sport” (or “sportsman/men”) is only used in reference to bloodsports, in particular hunting— both fox and hare hunting, as the mention of “foxhounds or the harriers” suggests (Kickham, 160, 340, 469, 470, 482–3)—and bird-shooting (Kickham, 89–93, 608, 610).[8] Admittedly, the term “sport” is used in relation to a description of bull-baiting (Kickham, 431–7), but the novel explicitly calls into question its status by describing onlookers as “struck with the cruelty of the ‘sport’ they had been watching so eagerly” (Kickham, 436).[9] While bull-baiting is depicted as a pastime for peasants and farm labourers, participation in the other bloodsports described in the novel is restricted to upper-class Protestants and affluent middle-class Catholics. Indeed, the expense of “sports” such as fox- and hare-hunting in the mid-nineteenth century put them beyond the means of all but the upper classes in Britain and Ireland. Furthermore, as Kickham notes, the necessity of a licence effectively made guns unavailable to the peasantry. Thus Hugh Kearney, son of an affluent tenant farmer, remarks:

“Don’t you know it is a crime to have arms in Ireland?” said Hugh, sarcastically. “No one can have arms without a licence, and men like Tom Hogan would not get a licence. So poor Tom has come to look upon never having fired a shot as a proof of his honesty and respectability.” (Kickham, 336)

The colonial-security aspect of denying guns to much of the population acquires a thinly-veiled political resonance in the film when Tom Hogan’s claim never to have handled a gun reassures the land-agent Pender as to the safety of evicting the small farmer and his family: ““Did you hear what he said? He never fired a gun—a safe man—a very safe man to evict” (Intertitle 96).

Kickham’s equating of sport with bloodsports exclusively is a reflection of his time. English and American dictionaries, Ikuo Abe has noted, confined their definition of “sport” to “skills in the field, like riding and hunting” until the 1880s and 1890s, when the term began to be applied more generally to athletic “or physically competitive activities” (Abe, 3, 24). The term’s changing application also reflected the codification of sports in the latter half of the nineteenth century, when what Harold L. Nixon II has identified as institutionalization, “bureaucratic organization”, and “rational calculation in the pursuit of goals, emphasis on task performance, and seriousness” came to “distinguish sport from other types of physical activities such as play, recreation, and games” (Nixon, 13). The emergence of sports codification was also a response to modernization processes and the need to provide structured leisure for rapidly changing and urbanizing societies (Waterson and Naughton, 3).

The film version of Knocknagow presents the prelude to one of these bloodsports when Barney Brodherick and Peg Brady (whom Barney is trying to seduce) stop to watch a hunting party and hounds. (Given their apparently different film stock, the images may have been taken from contemporary actuality footage.) Coming shortly after the hurling and hammer-throw episodes, the hunting scene contrasts sharply with the preceding sequences as regards both participation in the sport and its depiction more generally. Where the former had emphasized the athletes’ camaraderie and physical prowess, viewers are here offered the spectacle of the “Blooding of the Hounds” in which the bugle-toting hunt leader throws an apparently dead hare to the hounds (fig. 2) , who proceed to tear the animal to pieces, to the obvious enjoyment of the huntsmen and the cheers of Barney and Peg (fig. 3) . Although modern viewers are largely spared the full unpleasantness of this sequence because of the inferior picture quality, the scene is nonetheless disturbing, not least because of the protagonists’ pleasure at the evisceration of the hare. The association of hunting with the British aristocracy and the Anglo-Irish gentry, here signalled by the traditional costume worn by members of the hunt, may well have caused nationalist audiences to view this scene with some suspicion. In the narrative, too, the hunt plays a indirect role in the conspiracy to frame Mat Donovan: Barney, who has been charged by Maurice Kearney with taking a rifle to Mat for repair, is distracted by the hunt and hides the gun behind a wall, where it is first removed by Mick Brien, an evicted peasant, and eventually used by Pender to charge Mat with robbery.

Hurling

Coming almost half an hour into the film, the hurling sequence and the hammer-throwing sequence follow scenes that establish Knocknagow’s setting using romantic landscape shots of County Tipperary and the village of “Kilthubber” (in fact, Kickham’s home town of Mullinahone). At first glance, they would appear to contribute little to the overall development of the film’s episodic narrative. Yet the location of the hurling match has a special importance by virtue of Tipperary’s significance for the sport of hurling.

By 1918, the Tipperary associated in Kickham’s novel with oppression and suffering at the hands of corrupt land-agents, had become the centre of a resurgent Irish culture in which the GAA played a key part. County Tipperary was the birthplace of the GAA—founded in 1884 in the town of Thurles—and the home of some of the most successful players and teams in the history of Irish sport. Maurice Davin (fig. 4) , a Tipperary native, was invited by Michael Cusack to become the association’s first president because of his formidable achievements as an athlete in the weight-throwing disciplines—disciplines whose significance for both Irish nationalism and Knocknagow has already been noted—and in his lifetime Davin came to be regarded as one of the greatest athletes in Great Britain or Ireland (Cronin et al., 18–19). The county also had a highly distinguished record in hurling. Winners of the first hurling All-Ireland Final in 1887, Tipperary had added another nine titles by the time Knocknagow was released as a film. Charles Kickham’s “Slievenamon,” popularly regarded as the local anthem of County Tipperary, has long been sung at important Tipperary hurling games, and Kickham’s own name is now incorporated into those of several GAA clubs.[10]

In the novel, the hurling game is eagerly anticipated with repeated references to the upcoming “long disputed hurling match” between “the two sides of the river” (Kickham, 341, 68). However, the match itself is eventually cancelled when the opposing team’s captain, Tom Cuddehy, fails to appear. Instead the teams play a “promiscuous match . . . . wudout any regard to the two sides” (Kickham, 448). Apparently more a bit of fun than a serious encounter, it serves as a prelude to the main sporting event: the throwing of the sledge. Although the film offers no such qualification for its hurling game, the encounter shown does seem “promiscuous” insofar as it is difficult to identify teams since the players chase after the ball en masse. Even in the nineteenth century, opposing teams customarily wore “distinguishing colour or dress” (King, 26) yet these are either not evident or impossible to distinguish in the black and white photography of the film, in which all the players are dressed similarly in shirts and breeches (fig. 5) . Given hurling’s nationalist connotations, the fact that the teams are playing a “friendly” may also have had an ideological significance: contrasting the players’ cultural connectedness and good-humour with the fierce rivalry and occasional violence—a concern raised by the local priest in the novel (Kickham, 68)—that are a feature of hurling matches.

Despite its brevity, the hurling match in the film is nonetheless revealing. The style of play indicates that the game being played is the ground-based sport as it was practiced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when—in contrast to modern hurling, in which the sliotar (ball) is more frequently played in the air—players were forbidden to handle the sliotar. The shape of Mat’s hurley stick, with its longer and narrower boss (fig. 6) , similarly corresponds to the older form, described by Diarmuid O’Flynn as “long, narrow, sharply-curved, heavy-heeled” and as meant to make “hitting off the sod that little bit easier” (O’Flynn, 309). The shape of the hurley changed significantly as the game evolved in the twentieth century. The slower game, as seen in Knocknagow, “emphasised ground hurling, hip-to-hip combat, and encounters of strength”, became the possession-focused game that “demanded getting the ball into the hand, and . . . in turn required a more manageable stick that made it easier to pick up the ball off the ground” (King, 33), as evidenced by the wider boss of modern hurley sticks (fig. 7) .The film’s director, Fred O’Donovan, and those involved in the production may have deliberately omitted team colours in order to denote the “promiscuous” nature of the game, presuming that audiences would be familiar with the scene from the Kickham’s popular novel. The match sequence shows a ball being thrown in among the players, who then compete for possession, but it is very difficult to identify the ball once play begins. Hurling was ill-suited to the cinematographic style of Knocknagow, which relies on fixed camera positions and angles and uses only limited panning movements, as can be seen in the sequence when the hurlers run out of view as the ball is played to the left of the camera before coming back into view. The challenge of trying to film the game of hurling may also have contributed to the decision to only include a very short sequence, barely 40 seconds, in contrast to the hammer-throwing sequence, which lasts for over three-and-a-half minutes.

In both novel and film, the hurling match is followed by another contest when “Captain French, who had won great honors as an athlete in London, challenges Mat to the throwing of the hammer” (Intertitle 61). The pairing of these two sports was not unusual in the nineteenth century, when several sporting events could be held on the same day and when games of hurling or football were, indeed, sometimes stopped in order to allow wrestling bouts (see Kinsella).

“The throwing of the hammer”

A popular item at Irish fairs and athletic gatherings in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, weight-throwing has a far older history in Ireland:

The tradition went back as far as Cuchulainn, hero of the Red Branch Knights, who, legend has it, could throw a huge stone, lashed to the wooden beam of a chariot wheel, prodigious distances. This was the era of the Tailteann Games, the oldest of all sporting festivals, which dates from 1829 BC. . . . During the Middle Ages, the makeshift implements thrown by the ancient warriors were replaced by items such as the sledge-hammer used by blacksmiths. (Waterson and Naughton, 21)

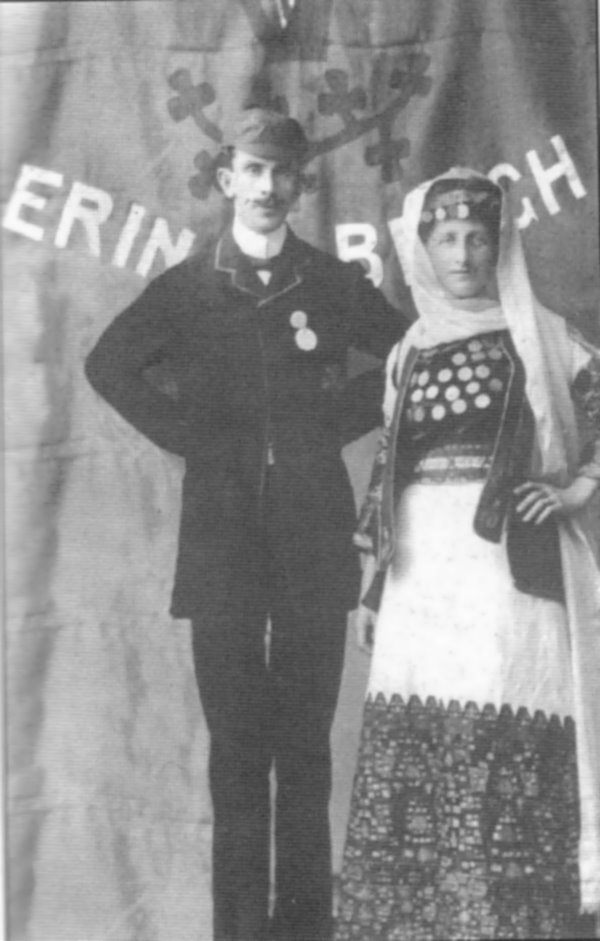

That “throwing the sledge” (Kickham, 440) in the novel is retitled in the film as “the throwing of the hammer” (Intertitle 61) likely reflects a concern on the part of the film’s producers to connect with the recent achievements of Irish-born athletes in this event at the Olympic Games. These achievements had received considerable coverage in the Irish press and had strong political resonance in that the Olympic Games provided an important forum for Irish-born athletes to express their national identity (see Quinn, 167). The most famous example was Peter O’Connor, whom the Irish Amateur Athletic Association chose to represent Ireland at the 1906 Intercalated Olympic Games in Athens, where he won gold in the hop, step, and jump (now the triple jump) (fig. 8 ) as well as silver in the long jump. In protest at being put on the British team and having his victory commemorated by the Union Flag, O’Connor scaled a flagpole in the middle of the field, unfurling a large green flag with the inscription Erin go Bragh (Ireland Forever) above the symbols of a harp and a gold branch (see fig. 9) (Quinn, 184–5). He was assisted in this by another Irish athlete, Con Leahy, who also waved a similar flag (Quinn, 199).[11] It was one of the first overt political acts in modern Olympic history.

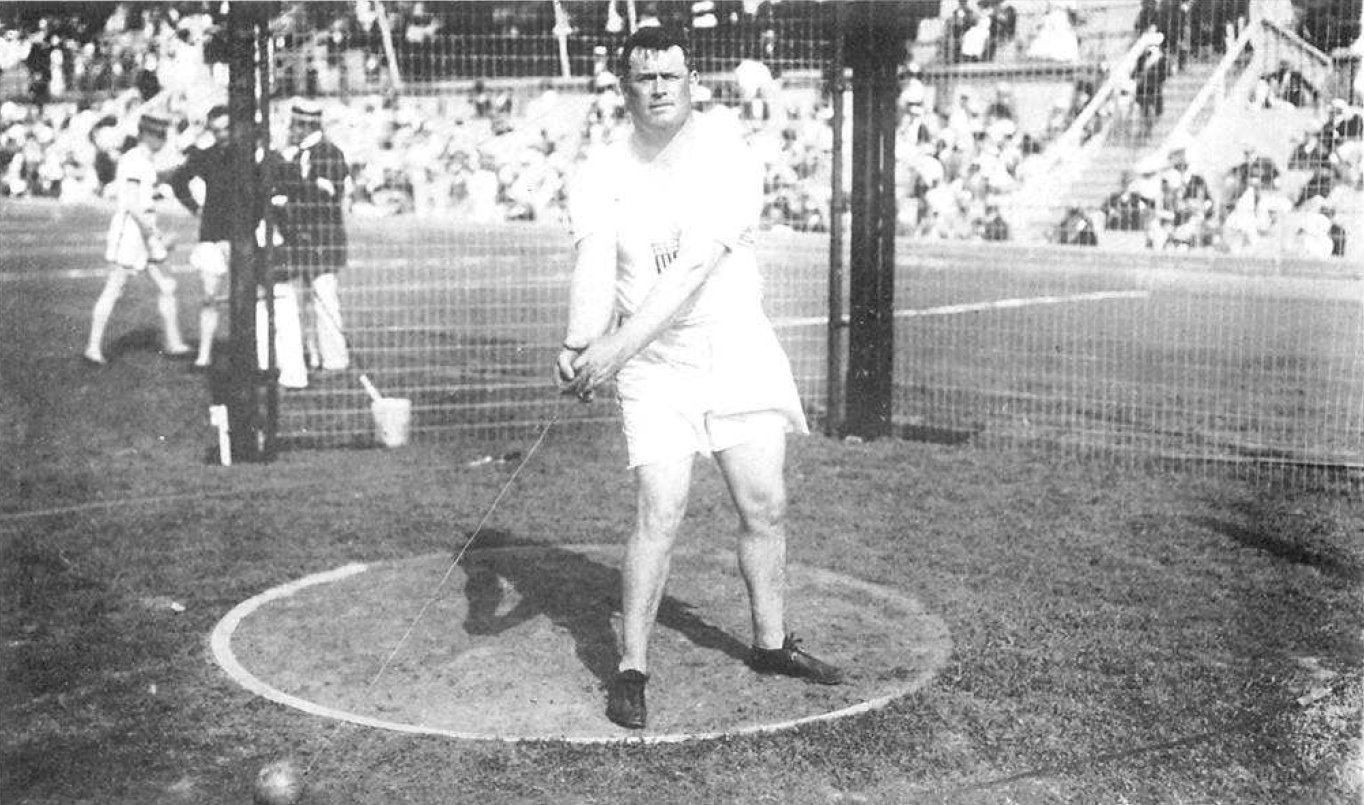

Irish-born athletes dominated the weight-throwing events every year between 1900 and 1932 in which the Olympic Games were held, winning gold in the hammer-throw at each event with the exception of 1924, when an Irish-born athlete nonetheless took silver. Prior to Irish independence, these athletes were overwhelmingly Irish emigrants to the United States, under whose flag they competed.[12] The international successes of these Irish-born athletes, who were known as the “Irish Whales,” was well-documented in the Irish press of the time, and Mark Quinn has described the “intense interest in all sections of the Irish Press” in the fortunes of Irish athletes at the 1906 Intercalated Games (Quinn, 167). During the Olympic Games in Stockholm in 1912, the only Games held before the release of Knocknagow, the Irish Independent prominently featured a drawing of Patrick “Fat Mac” McDonald, shot-put champion and native of County Clare, under the headline “Irishman’s World Record” (fig. 10) .[13] Knocknagow’s depiction of Mat Donovan as a heroic hammer-thrower could also have reminded Irish audiences of another Irish-born athlete: Matt McGrath (fig. 11) , a Tipperary man who had won gold for the United States in the hammer-throw at the 1912 Olympics and received a great reception in his home town of Nenagh (Nenagh Guardian, 26 July 1912, 3 August 1912).[14]

While the dominance of the Irish in the hammer throw reflected in part the popularity of weight-throwing at sports meetings and festivals in Ireland, it has been suggested that the Irish brought to the event a style and approach that gave them a distinct advantage over their international challengers. In Johnny Waterson and Lindie Naughton’s Irish Olympians 1896–1992, the technique is described using Kickham’s own account of Captain French’s throw in Knocknagow:

He took the heavy sledge, and placing his foot to the mark, swung it backwards and forwards twice, and then wheeling rapidly full round, brought his foot to the mark again, and, flying from his arm as from a catapult, the sledge sailed through the air, and fell at a distance that seemed to startle many of the spectators. (Kickham, 452)

While French is marked in the novel as an officer in the British army, the son of a local landlord, and an “aristocrat” (Kickham, 391), he is also clearly identified as a Tipperary native. The film at no point acknowledges this important distinction, instead presenting French as merely an athletic British officer in the attire of the upper class, and thereby accentuating the political connotations of Mat’s battle to defend the honour of Knocknagow against an unidentified stranger.

It is particularly significant, then, that the passage just quoted does not accurately describe how the film portrays French’s throw, which involves little or no foot movement (fig. 12) . Rather, it is Mat’s final victorious throw, with its characteristic “wheeling rapidly full round” before releasing the hammer (fig. 13) , that is closest to the style evinced by French in the book. In attributing to Mat what had become known as the “Celtic style” of hammer throw (Waterson and Naughton, 21–22), the filmmakers again connected “Mat the Thrasher” to successful Irish-born athletes whose victories in this discipline owed much to their distinctive foot movement during the wind-up part of the throw.

As the intertitle emphatically tells us, Mat’s winning throw is inspired by a concern that “for the honour of old Knock-na-gow I must win” (Intertitle 66). The sentiment is similarly highlighted in the novel when Mat, just prior to his third and final attempt, cries: “For the credit of the little village!” (Kickham, 453). In the twentieth century, concern for the “little village” became a defining aspect of the development of Irish sport, particularly games promoted by the GAA.[15] The GAA’s decision in 1887 to divide Gaelic football and hurling clubs by parish ensured that Gaelic games would be defined by place—a crucial factor in their subsequent popularity. In turn, the use of county boundaries at the elite level of the sport played a crucial role in the growing significance of the county for Irish people’s sense of identity. However, the precedence of club (parish) over county in the early years was evident in the choice of the winning club in each county to represent the county in the major national competition, the all-Ireland championship, a practice that continued into the first decade of the twentieth century. Indeed, in an obituary for the great Wexford hurler, Billy Rackard, the Irish Independent recently noted: “Charles Kickham had produced a blueprint for the GAA when he wrote Knocknagow five years before the Association was founded. The honour and the glory of the little village was what Kickham espoused. The GAA nursed the concept into being” (The Other Rackard). The GAA’s local focus remains important, particularly in rural communities, for whom it provides a point of communal association and support. Reflecting recently in the Observer on the killing of Ronan Kerr, a police officer and GAA player, and the support provided by the community for his relatives and friends, Fintan O’Toole stressed the significance of Mat’s famous declaration:

The hero of the classic GAA novel, Charles Kickham’s Knocknagow, published in 1873, is a farm labourer who goes on to the hurling field with the cry: “For the credit of the little village!” GAA players still take the field for the credit of all the little villages—not just the literal ones like Ronan Kerr’s Beragh, but the psychological villages to which we cling in a globalised culture—the idea of a place, of a community, of something that is not yet owned by a TV company or a corporation. (O’Toole)

It is often remarked by the GAA and commentators alike that the Association’s strength lies not in the inter-county game but in the parish-based model, where communities are affirmed and revolve around their local club.[16]

Conclusion

The depiction of Irish sport in Knocknagow (1918) is highly significant, not only for audiences during the film’s initial release but for all those interested in sport in Ireland.

The film’s sporting scenes responded to a widespread and growing demand for moving images of sport, a demand that dates from the earliest days of the cinema. Indeed, journalistic accounts of the first screenings laid special emphasis on the sporting sequences, suggesting that they were particularly appreciated by audiences. Thus The Anglo-Celt reported of a showing in Cavan town:

The happy peasantry, the prowess of the youth at the hurling match, the hammer-throwing contest, the unexpected “hunt,” the love scenes and the comedy—the life as it was before the agent of the absentee landlord came like a dark shadow on the scene, and with crowbar and torch, laid sweet Knocknagow in ruins—all were depicted by the very perfect actors who made up the cast. (2 March 1918)

Another contemporary review in the Watchword of Labour remarked on the sporting elements in the film and described “Mat the Thrasher” as “always first in the hurling field and other manly sports” (27 December 1919). The reviewer’s reference to “manly sports” reflects the meaning of sport in the film’s affirmation of Mat Donovan’s masculinity, a trope evident in the promotion of sport across Ireland during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries as both sport and film served to popularize national sentiment. Knocknagow (1918) provides a rich example of this process, echoing the association of hurling with contemporary Republicanism and portraying hammer-throwing as a contest between an Irish peasant and a representative of the British establishment.

The film’s sporting scenes also have an international dimension in implicitly recalling the extraordinary successes of Irish-born athletes in the weight-throwing disciplines at the Olympic Games, successes that may well have influenced the film’s retitling of the novel’s “throwing the sledge” as “the throwing of the hammer”. Sport in the film serves as an important marker of social class, notably the association of hurling with a rural working classes whose desire for structured leisure pursuits had partly prompted the founding of the Gaelic Athletic Association. Finally, Knocknagow stands as a cinematic record of the sports concerned, offering valuable visual details of the ground-based style of hurling, the narrower shape of the hurley stick, and the hammer-throwing technique that had underpinned the international success of Irish-born athletes. By highlighting the importance of local identity to Irish people, this fascinating film reaffirms the focus of the Gaelic Athletic Association, one that remains of central relevance to its role in contemporary Irish society.

Images

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4. Maurice Davin, first President of the GAA, wearing some of the more important medals won during his outstanding sporting career. Reproduced by kind permission of Mike Cronin, Mark Duncan, and the GAA Oral History Project.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Figure 7. A hurley stick as used in the game of hurling today with a much wider boss. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hurling_Ball_and_Hurley.JPG.

Figure 8. Peter O’Connor taking gold in the hop, step, and jump at the 1906 Intercalated Olympic Games. By kind permission of Liffey Press.

Figure 9. O’Connor and his wife standing in front of the Irish flag he flew in protest at the 1906 Intercalated Olympic Games. By kind permission of Liffey Press.

Figure 10. Irish Independent, 11 July 1912.

Figure 11.

Figure 12.

Figure 13.

Works Cited

Abe, Ikuo. 1988. A Study of the Chronology of the Modern Usage of “Sportsmanship” in English, American, and Japanese Dictionaries. International Journal of the History of Sport 5.1 (December): 3–28.

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Anglo-Celt (Cavan).

Athletics Men’s Stone Throw Medalists. http://www.sports-reference.com/olympics/sports/ATH/mens-stone-throw.html. Accessed 2 February 2011.

Bergvall, Erik, ed. The Official Report Of The Olympic Games Of Stockholm 1912 Issued By The Swedish Olympic Committee. Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 1913.

Billig, Michael. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage Publications.

Clegg, Brian. 2007. The Man Who Stopped Time: The Illuminating Story of Eadweard Muybridge—Pioneer Photographer, Father of the Motion Picture, Murderer. Washington: Joseph Henry Press.

Condon, Denis. 2008. Early Irish Film, 1895–1921. Dublin: Irish Academic Press.

Croke, T. W. 1884. Letter to Michael Cusack, 18 December. http://multitext.ucc.ie/d/Archbishop_Croke__the_GAA_November_1884. Accessed 20 October 2011.

Cronin, Mike. 1999. Sport and Nationalism in Ireland: Gaelic Games, Soccer and Irish Identity since 1884. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

Cronin, Mike, Mark Duncan, and Paul Rouse. 2009. The GAA: A People’s History. Cork: The Collins Press.

Crosson, Seán. 2009. Gaelic Games and “the Movies”. In The Gaelic Athletic Association, 1884–2009, ed. Mike Cronin, William Murphy and Paul Rouse, 111–36. Dublin: Irish Academic Press.

Crosson, Seán, and Dónal McAnallen. 2011. “Croke Park goes Plumb Crazy”: Gaelic Games in Pathé Newsreels, 1920–39. Media History 17, no. 2 (May): 161–76.

de Búrca, Marcus. 1980. The G.A.A.: A History. Dublin: Cumann Lúthchleas Gael.

Gellner, Ernest. 1983. Nations and Nationalism. Oxford: Blackwell.

Gunning, Tom. The Cinema of Attraction. 1986. Wide Angle 8.3: 63–70.

Irish Independent (Dublin).

Kickham, Charles J. 1979. Knocknagow; or, The Homes of Tipperary. First published in 1873. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan

King, Seamus J. A History of Hurling. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Kinsella, Eoin. 2009. Riotous Proceedings and the Cricket of Savages: Football and Hurling in Early Modern Ireland. In The Gaelic Athletic Association, 1884–2009, ed. Mike Cronin, William Murphy, and Paul Rouse, 15–31. Dublin: Irish Academic Press.

McCarthy, Larry. Irish Americans in Sport: The Twentieth Century. In Making the Irish American: History and Heritage of the Irish in the United States, ed. Joseph Lee and Marion R. Casey, 457–74. New York: NYU Press.

McDevitt, Patrick F. 1997. Muscular Catholicism: Nationalism, Masculinity and Gaelic Team Sports, 1884–1916. Gender & History 9.2 (August): 260–85.

McKernan, Luke. 1996. Sport and the First Films. In Cinema: the Beginnings and the Future, ed. Christopher Williams. London: University of Westminster Press.

Monks, Robert. 1996. Cinema Ireland: A Database of Irish Films and Filmmakers, 1896–1986. Dublin: National Library of Ireland.

Nenagh Guardian.

Nixon, Howard L., II. 1984. Sport and the American Dream. Champaign: Leisure Press / Human Kinetics.

O’Callaghan, Liam. 2011. “The Red Thread of History”: The Media, Munster Rugby and the Creation of a Sporting Tradition. Media History 17.2 (May): 175–88.

O’Flynn, Diarmuid. 2008. Hurling: The Warrior Game. Cork: The Collins Press.

Ó hEithir, Breandán. 1991. Over the Bar. Dublin: Poolbeg.

The Other Rackard. 2009. Irish Independent, 28 March.

http://www.independent.ie/obituaries/the-other-rackard-1689696.html. Accessed 5 June 2011.

Quinn, Mark. 2004. The King of Spring: The Life and Times of Peter O’Connor. Dublin: The Liffey Press.

Rockett, Kevin. 1988. The Silent Period. In Cinema and Ireland, ed. Kevin Rockett, Luke Gibbons and John Hill, 18–23. First published in 1987. London: Routledge.

—–. 2004. Irish Film Censorship: A Cultural Journey from Silent Cinema to Internet Pornography. Dublin, Four Courts Press.

Streible, Dan. 2008. Fight Pictures: A History of Boxing and Early Cinema. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Synge, John Millington. 2004. The Playboy of the Western World, introd. Margaret Llewellyn-Jones. London: Nick Hern.

O’Toole, Fintan. 2011. Can the Queen win over Croke Park? Observer, 8 May.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/may/08/queen-britain-croke-park-ireland. Accessed 9 May 2011.

Waterson Johnny, and Lindie Naughton. 1992. Irish Olympians 1896–1992. Dublin: Blackwater Press.

Watchword of Labour (Dublin).

Wilcox, Ralph C. 1995. The Shamrock and the Eagle: Irish Americans and Sport in the Nineteenth Century. In Ethnicity and Sport in North American History and Culture, ed. George Eisen and David Kenneth Wiggins, 55–74. Westport: Praeger Publishers.

[1] I would like to acknowledge the research support of NUI Galway’s Millennium Conference Travel Assistance Fund.

[2] The date of the novel’s setting is discussed in Irish Limelight, May 1917, 6 (see Appendix D).

[3] On newsreel coverage of Gaelic games, see Crosson and McAnallen. On Gaelic games in twentieth-century film, see Crosson.

[4] Cusack provided the model for the character of “The Citizen” in James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922).

[5] Celtic Times, 26 February 1887, quoted in McDevitt 273.

[6] See Athletics Men’s Stone Throw Medalists. Although the Intercalated Olympic Games were to be a series of International Olympic Games held in Athens mid-way through the four-year cycle of the modern Olympic Games, they were only held in 1906. For more detail, including Martin Sheridan’s performance as the “absolute star” (winning five medals, with gold in the shot-put and discus), see King 162–4 and 194–5.

[7] For a description of an early-twentieth-century form of stone-throwing played in the Aran Islands, see Ó hEithir 12–13.

[8] The novel also mentions a tiger hunt in India (Kickham 591).

[9] Outlawed by the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1835, bull-baiting appears nonetheless to have continued in the mid-century rural Ireland that Kickham describes.

[10] For example, Kickhams Creggan (Antrim), Ballymun Kickhams (Dublin), Cooley Kickhams (Louth), and Knockavilla-Donaskeigh Kickhams (Dundrum, West Tipperary).

[11] O’Connor was not the first Irish athlete to attempt to make a political point at the Olympic Games. At the first modern Olympics in 1896, John Pius Boland, later Member of Parliament for South Kerry, took gold in the singles and doubles tennis events. When a Union Flag was being hoisted to mark his victory, Boland protested that he was Irish: an Irish flag similar to that later hoisted by O’Connor was flown—the first use of an Irish flag to mark an Irish victory at an Olympic event (Waterson and Naughton 4).

[12] On the “Irish Whales”, see McCarthy; Wilcox; and Waterson and Naughton 5–6, 22–23.

[13] The 1916 Olympics were cancelled because of the First World War.

[14] A statue of McGrath was erected in Nenagh in September 2002 to commemorate his Olympic achievements. Interestingly, at least two Irish-born athletes at the Olympic games in the early twentieth century professed to have drawn inspiration from Kickham’s novel. McGrath told an interviewer, “I longed to be worthy of the race of that fine prototype of the Gael, Matt Donovan, the hammer-thrower of Knocknagow, drawn so brilliantly by the patriot, Kickham” (Nenagh Guardian, 14 September 1918), and another Tipperaryman, James Mitchel, who won an Olympic medal in weight throwing, claimed to have been “stimulated” by Mat’s defeat of Captain French “to emulate the glorious deeds of the hero of ‘Knocknagow’” (Nenagh Guardian, 10 September 1921).

[15] On the importance of the largely invented local allegiances and identities which have been asserted for provincial Rugby Union teams in Ireland, particularly since the sport was professionalized in the 1990s, see O’Callaghan.

[16] At the 2003 GAA Annual Congress, for example, then President of the GAA, Seán Kelly, remarked on “the importance of the local GAA club to the Association. The GAA club is the cornerstone of the Association and the needs of the GAA Club must be addressed” (GAA website, “Club Planning and Development” http://www.gaa.ie/page/club_planning_and_development.html [accessed 27 October 2007]). Indeed, its mission statement continues to stress that the Association is “a community based volunteer organisation promoting Gaelic Games, culture and lifelong participation” (GAA website, “Administration” http://www.gaa.ie/about-the-gaa/mission-and-vision/ [Accessed 28 March 2011]).