Since Australia’s film renaissance from the mid-1970s, there have been numerous films featuring Asian characters in both leading and marginal roles. This paper traces the historical representation of Asian characters in Australian feature films, focusing on films from the 1920s as establishing some of the earliest tropes that have persisted through to contemporary examples. Character types—from the cook to the suburban restauranteur, servant and laundry maid, to an assortment of dragon ladies, drug dealers, gangsters and thugs—continue to inhabit Australian screens just as they did since the inception of film in this country. Drawing attention to this historical connection may be a catalyst leading to an eventual break in the chain of representation.

In order to highlight films featuring marginal Asian characters from the period of Australian silent cinema, it is useful to place particular examples, such as The Birth of White Australia (Philip K. Walsh, 1928), The Menace (Cyril J. Sharpe, 1928) and A Girl of the Bush (Franklyn Barrett, 1921), within a broader international frame of cinematic modernisms of the 1920s. Taking as a point of departure William D. Routt’s argument that Australian film modernism of the period, such as it exists, can be identified as a way of distinguishing white Australia from Great Britain, this essay focuses instead on the continued under-acknowledgment of non-white characters in the films as formative of the national cinema’s modernity. [1]

Australian cinema of the 1920s is not unified or coherent enough to be described as an art movement, unlike the more established European modernisms of the 1920s including German Expressionism, Russian Formalism, and French Impressionism, or even American slapstick, whose urbanism and dynamism “aligned [it] with the modernity of the New World”. [2] Rather, Australia’s films of the period are marked by their populism, working class origins, humour, and sentimentality. Any elements of stylistic modernism manifested in Australian films of the 1920s were deployed more for popular appeal than for “art’s sake”, and to announce the films’ “Australianness” or cultural difference against England.

Routt lists some of the ways in which modernism was expressed in Australian films of the period, including:

- In overt narrative formalism, symbolism and moral equivocation derived from Victorian melodrama;

- In cross-media references and other gestures pointing outside the film world to a world understood as modern (for example, to the effects of newspapers, aeroplanes, radio …);

- In the use of visual ‘documentary realism’ in conflict with filmed narrative;

- In certain deliberately ‘cinematic’ sequences (including instances of ‘self-referentiality’). [3]

With the exception of the few films in which these elements were incorporated, modernism did not have a strong impact on the industry at that time. [4] Routt observes:

The fate of modernism in Australian films of this period is intimately tied up with white Australia’s conflicted relationship with England and its attempts to make a cultural identity out of its populist working-class and outcast understanding of its origins. Modernism, because of its clear aesthetic and intellectual aspirations, could find little overt place in the popular entertainment which characterised the Australian film industry of the period. It would have to wait until the late 1950s before making a deliberate and substantial impact. [5]

In order to explore a different perspective on the issue of cinematic modernism, it is perhaps more revealing to take up where Routt left off in his article; that is, to examine the treatment of non-white peoples in the films of this period and to consider how this also contributed to an aspect of Australia’s cinematic “modernism”. As Routt notes, “cinematic modernism invokes questions of art, of social critique … [as well as of] national identity”. [6] Beyond white Australia distinguishing itself from the British Empire (through the cinema’s embrace of populism rather than “artistic” modernism), Australian national identity was also forged through an emphasis on social fissures within the nation itself, for example, between white Australians and non-white immigrants. [7] Routt does acknowledge that many films of the period “deal in diverse ways with ethnic differences” including A Girl of the Bush; The Menace; The Birth of White Australia; The Jungle Woman (Frank Hurley, 1926) and The Devil’s Playground (Victor Brindley, 1928), but he does not elaborate on this observation. [8] I wish to continue where Routt left off by looking specifically at how non-white people (in particular Asian characters), were treated or represented in these films and their contribution to creating the cinema’s modernity. [9] This aspect of early Australian cinema remains largely unacknowledged in the scholarly literature of the period.

Asian Characters in Pre-1920s Australian Cinema: The Influence of World War I

Before focusing on the period of the 1920s, it is useful to examine the industry as it existed prior to that time. Since the inception of feature filmmaking in Australia in the early 1900s, a majority of films have dedicated themselves to establishing the relationship between white settlers and the land. [10] With the advent of World War I, however, Australia was forced to (re)consider its position not only vis-à-vis the United Kingdom but in relation to the rest of the world. The periods prior to and immediately after World War I were buoyant times for Australian film production companies. Film historian Eric Reade refers to the period of 1911-1913 as “The Golden Period” during which war propaganda films abounded. Similarly, following the war the number of foreign films entering the country was reduced, thereby providing a further boost to Australian production companies. [11]

The resulting insularity of the industry meant that the cinema of the period was remarkably devoid of any representations of non-white “Australianness”, including indigenous Australians, other than as obstacles to be removed in the taming of the land. There were only two films prior to the 1920s that commented on an Asian presence in Australia to any degree. These films, Raymond Longford’s Australia Calls (1913) and Beaumont Smith’s Satan in Sydney (1918), will be mentioned briefly for the social environment they portrayed and the cinematic tropes they introduced in the period directly preceding the 1920s. Both films provide an early reflection of Australia’s exposure to its Asian neighbours in the period preceding and directly following World War I.

Longford’s Australia Calls draws on fears of the “yellow peril” at that time by depicting a military attack on Sydney by Asian “invaders”. [12] The opening scenes of the film show Australians at the beach, the race track, and the football and “over each scene is superimposed a looming vision of a menacing Asiatic invader.” [13] From her outback station, the film’s protagonist, Beatrice Evans (Lottie Lyell), hears of the attack on the Sydney Mint, the Treasury and a wireless telegraphy station; that is, money and communications are targeted. Also enlisting in the fight against the invaders are the indigenous Australians who turn on the local Chinese, including a cook. A suitor spurned by Beatrice becomes a traitor, working as a guide for the Chinese. Beatrice is captured but eventually rescued; the Asians are defeated and peace is restored.

Significantly, the Chinese and the Japanese served as allies during World War I and should technically have been considered on the same “side” as Australia. As something of a concession to this fact, Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper note: “to avoid embarrassment to the government’s relations with the Japanese, the nationality of the ‘yellow peril’ was not specified” (p. 51). The enemy were referred to as “Mongolians” (p. 51) and portrayed alternately as Chinese, Japanese and as “Asiatics” in general. [14] Extras recruited to play the enemy were selected from Sydney’s local Chinese community, although a leading Asian commander was played by Andrew Warr in yellowface (p. 51). Alternately considered “patriotic” and “xenophobic”, the film plays into a fear of Asians that existed in Australia prior to World War I. [15] Furthermore, despite their allied contributions during the war, the film nevertheless “expressed feelings that lay not far beneath the surface of Australian society for many years” (p. 52).

Beaumont Smith’s sixty-six minute film, Satan in Sydney, features two enemies: the Germans and the Chinese. An innocent country girl, Anna Maxwell (Elsie Prince), is banished from home by her parents when she becomes scandalously associated with her German choirmaster, Karl Kroner (Charles Villiers). Anna finds her way to Sydney just as the war breaks out. Kroner, also in Sydney, opens a gambling hall and Chinese opium den where he employs women to encourage men to desert from the army (p. 106).

The film was scheduled to open at the Lyric Theatre in Sydney on 15th July 1918, however Smith did not seek clearance to screen the film. It was shown for only one day before police demanded the screenings be stopped. District Licensing Inspector, J. Fullerton, regarded scenes in “a Chinese grog shop with a number of our Australian troops in a drunken condition … very offensive to Chinese, who are our allies” (p. 106). The newly formed New South Wales Film Censorship Board overruled Inspector Fullerton’s decision, stating that the Chinese community were unlikely to be offended. The film was therefore released uncut, with the proviso that if the Chinese community complained, the film may be reassessed (p. 106). Screenings resumed and crowds poured in to view the sensational “uncensored” production. [16] The Chinese community in fact did object, not to the film itself but to its publicity, which more than implicitly portrayed the Chinese as the “Satan” of the film’s title (p. 106). [17] While the censors did not have jurisdiction over publicity material, they formally requested the Lyric management remove the posters, which they complied with, having already profited from the film’s temporary ban which made it all the more appealing (p. 106).

Smith’s film played into racist attitudes towards Germans and Chinese, already witnessed in Longford’s earlier film Australia Calls. These attitudes reflected the White Australian Policy and related government policies still in place at that time. However, social problems of drugs, prostitution and gambling continue to be associated heavily with Asians in Australia (Chinese and Vietnamese in particular), and remain prevalent in films such as Rowan Woods’ Little Fish (2005) even after official policy changes. [18]

This brief survey of the period prior to the 1920s reveals that by the end of World War I, a new sense of nationalism and nationhood, one that was not tied to the British Empire, was being fostered. [19] This marks the beginning of a period of cinematic modernity for Australia as a unique, film-producing nation:

The ten-year period from 1914 to 1924 brought with it new concepts of Australian nationalism through the momentous upheaval of the First World War and the difficult period of postwar readjustment. The valour of Australians on the battlefield kindled the spark of nationalistic fervour; later a nationalism of a more complex kind was inflamed amid sharp community divisions over conscription and a questioning of Imperial ties. Within Australia’s film industry, two periods of boom were followed by signs of irreversible decline. … In purely local terms, the nationalistic impulse of filmmakers and audiences was enough to keep the industry alive throughout most of the 1920s. [20]

The specificity of Australia’s cinematic modernity during the 1920s will now be considered.

1920s Australian Films

In comparison to the decade before it, the 1920s was a relatively quiet time for Australian filmmaking. This is despite the fact that some of the enduring classics of Australian cinema were produced during this period, including Raymond Longford’s On Our Selection (1920) and Franklyn Barrett’s A Girl of the Bush (1921). Eric Reade refers to the period 1920-1923 as “The Desperate Years”, signifying a time when Hollywood began to dominate the local market. From 1923, approximately 94% of the films screening in Australia were from America. [21] Of the Australian films that were made, most were in the form of newsreels. The latter half of the 1920s, just prior to the introduction of sound in film, saw the beginnings of The Great Depression (1929-1932), which further contributed to a lack of pioneering filmmakers.

Despite the lull in the industry, it is worthwhile focusing on the period of the 1920s, following World War I, since this decade saw the beginnings of a greater awareness towards, coupled by an anxiety over, foreign “Others” and the protection of Australian borders (against “villains” alternately portrayed as German, Japanese and Chinese). These concerns take on renewed import today as fears over border control and so called “boat people”—refugees and asylum seekers—escalate with the policing of Australia’s waters.

As mentioned at the beginning of the paper, after the war Australia was keen to distinguish British identity from a burgeoning Australian cultural identity. In 1925, the Commonwealth government released the first of what was to become a series of approximately fifty short films under the general title, Know Your Own Country. These films were aimed not only at local audiences, informing them of their country’s industries and resources, but they were also used to promote Australian trade and immigration to other countries (p. 116). Raymond Longford produced a second film entitled Australia Calls (1923) as part of the campaign to publicise Australia to the United Kingdom at the British Empire Exhibition of 1924-25. The film tells of two brothers who arrive in Australia and work hard to save and repay their debts until becoming successful citizens. [22] What was being valued and promoted in this film, however, was a very specific kind of (white) Australian citizenship. This is in marked contrast to the film of the same title produced by Longford ten years previously to portray an imaginary invasion of Australia by Asiatic hordes.

The emergent Australian cultural nationalism of the period also served to keep up the momentum of local filmmaking in the face of a growing dominance of imported film, especially from Hollywood. By the 1920s, most major Hollywood studios had branches in each Australian state, creating monopolies in the distribution network. Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper note, “The effect of Hollywood on the language and morals of Australian society became an issue of concern to many in the community during the 1920s, and their protests augmented the demand for more Australian content on the screen” (p. 116). Pressure was building among lobby groups regarding film censorship, local content quotas, and import duties, resulting in a Royal Commission of the Motion Picture Industry from June 1927 to February 1928. [23]

In light of these developments and concerns, particularly in positing Australian nationalism against British and American encroachments, what is the value of considering the place of vilified Others in the form of anti-Asian sentiment? It is argued that tokenism remains the predominant mode in which Asian characters are utilised in Australian cinema, marking the ubiquity of these character types, albeit in different social and political contexts. The token operates as a medium of exchange through which group identity, politics, and resistance are traded for economic and cultural capital, and it is this continual re-affirmation and re-definition of “Australianness” which marks the cinema’s modernity in the period of the 1920s and beyond. The representation of Asian characters as tokens operates as a third point of contention between Australian national identity and the British and American. However, in the various histories of early Australian film, particularly of the silent period, Asian characters in Australian films have not been considered at all. [24] This is despite the fact that Asian characters started appearing on Australian screens more significantly during the 1920s, following the two examples discussed prior to the 1920s. The omission of any discussion of Asian characters from the criticism of the period is no doubt due to the marginal nature of these characters; nevertheless, their presence and appearance is noteworthy for what they reveal about how Australian national identity was constituted, and modernised, at that time. Asian characters operated as tokens of exchange mediating between British and American identity formations yet remain overshadowed by these other considerations.

The notion of tokenism appeared controversially in recent Australian public life when Federal Opposition leader Tony Abbott criticised the government’s policy of acknowledging the traditional owners of the land as an “empty gesture”, lacking in sincerity: “There’s a place for this in the right circumstances but certainly there are many occasions when it does look like tokenism”. [25] Glen Kelly, spokesperson for the South West Land and Sea Council in Western Australia argued that acknowledgment was necessary: “It’s not tokenism, it’s actually recognition”. [26] In the case of film, tokenism also involves more than just numbers or screen time. It is a matter of significance, or recognition. [27] Tokenism appears to offer inclusion or mobility to the minority group but this is in fact a restricted mobility. [28] The following sections will outline some of the key tropes used to represent Asian characters in 1920s Australian films according to a logic of tokenism that continues to trade on Asian identities into the contemporary period.

The Cook

One of the earliest Australian films to feature a Chinese cook is Beaumont Smith’s The Gentleman Bushranger (1921). In this film, the cook, a comic character with buck teeth and a long gown, is played by actor John Cosgrove in yellowface. Not unexpectedly, the cook is also a treacherous character, involved in smuggling gold to Sydney with the film’s main villain, Peter Dargin (Tal Ordell).

Franklyn Barrett’s A Girl of the Bush was released in the same year as The Gentleman Bushranger and is one of Barrett’s only two surviving (complete) silent feature films (the other is The Breaking of the Drought, 1920). Barrett’s film features two Chinese characters, a cook and a laundry maid. While there is an historical truth to some of these stereotyped roles and occupations, the vilification of the characters is an ongoing cinematic invention. In Barrett’s case, the Chinese characters are employed as a parallel or foil to the film’s main (white) protagonists, providing a comic contrast.

In the film Lorna Denver (played by Vera James) is the manager of the wealthy Kangaroo Flat sheep station which she inherits from her guardian and father figure Jim Keane (D. L. Dalziel). Two suitors, Jim’s nephew Oswald Keane (Herbert Linden), and Tom Wilson (Jack Martin), a surveyor, vie for her affections. When Lorna takes on the care of a baby who survived an attack by Aborigines on white settlers, Tom is led to believe that the baby is her own. Hurt by this assumption, Lorna rejects Tom. Later, Oswald is murdered and Tom is arrested for the crime. It is eventually revealed by the Chinese cook, Sing Lee (Sam Warr), that Oswald was not murdered by Tom but by the father of the woman whose baby is now being taken care of by Lorna. Tom realises the truth about the baby and is reconciled with Lorna (p. 140).

What is interesting about this film for the purposes of this essay is the employment of Chinese characters in a film about a bush girl produced “during one of the Australian silent cinema’s most nationalistic periods.” [29] Anna Gardner comments:

The idea of the bush girl is one that is heavily representative of the many changes surrounding the Australian identity as it developed around the beginning of the twentieth century. There is a marked absence of the feminine in the early development of the Australian national type, as cultural pioneers (in particular the bohemian artists of the late 1800s) were trying to present an active, bush-orientated masculine image as the quintessence of Australianness. … However, the inter-war years (from 1919 to 1939) were characterised by a strong drive towards nation building and the taming of the land, and the girl of the bush was an apt symbol of the young, fertile, post-colonial ideal. [30]

The figure of the bush girl became a potent and enduring symbol from the 1920s to the late 1930s. This figure was often portrayed through the father-daughter relationship that figured in many films of the time, including A Girl of the Bush and The Squatter’s Daughter (Bert Bailey, 1910). Gardner writes, “The close relationship between the father (or father figure) and daughter can be read as echoing the imperial relationship between England and the empire.” [31] It is the bush girl who is associated with “ensuring the continuation of empire” [32] , or, as Deb Verhoeven puts it, she “encapsulates a national desire for prosperity through productivity”. [33] Viewed through this imperial analogy, the colony represents a continuation of empire.

Outside of this imperial framework, it is possible to consider a postcolonial alternative represented by the film. Critics often comment on the film’s “documentary realism”; its portrayal of scenes of station life, sheep shearing and horse breaking for example (p. 141). Graeme Turner suggests a line of continuity from this early film to those of the 1970s revival:

In A Girl of the Bush, minor characters (such as the Chinese cook) are introduced by way of a description of their function in the community rather than in the plot. Such ‘flat’ characters—ones used as indicators of social setting, group customs, community values and beliefs, rather than as particularised articulations or transformations of any of these—are very much in evidence in the films made during the 1970s revival. One of the consequences … of that period’s dominant mode of documentary realism was to subordinate interest in character to interest in social process, and to subordinate interest in narrative to interest in observation. [34]

Asian characters remain marginal, a token of exchange in what Turner notes as a “social process” that remains seemingly extraneous to the process of (gendered) nation-building. However, the figure of the Chinese cook endures more forcefully in Australia’s cinematic imagination. We see the figure of the Chinese cook or restauranteur in a number of recent Australian films, from Muriel’s Wedding (P.J. Hogan, 1994) to Love Serenade (Shirley Barrett, 1996), where awkward family moments (of the patriarch’s infidelity) take place around the table of a suburban Chinese restaurant in the former example. The Chinese restaurant has become so iconic that Bran Nue Dae (Rachel Perkins, 2009), features only one shot of an outback Chinese restaurant as pure sign or symbol; there is no need to even see or shoot inside it. The only aspect to this representation that has changed from the films of the 1920s is that yellowface performance would no longer be readily accepted or tolerated. Both the Chinese cook and the laundry maid in A Girl of the Bush are played by white actors; today, Asian actors are employed to stereotype themselves.

The Thief and Drug Dealer

Dunstan Webb’s fifty-five minute film, The Grey Glove (1928), concerns a detective trying to catch a criminal who always leaves a grey glove at the scene of his crimes. Unsurprisingly, in their travails to catch a murderer, the “good guys” must pay a visit to the iconic site of evil and vice, the Chinese opium den. Another short film, Cyril J. Sharpe’s twenty-three minute The Menace (1928), also depicts the Chinese as drug dealers. The title of the film ostensibly refers to the “menace” of drug trafficking in Sydney but can equally be taken to refer to the Chinese as the perpetrators of drug dealing. Only the last two reels of the film survive, telling the story of Robert Grainger, feared disappeared, who has taken on a disguise to find the murderer of his Chinese friend, Li Chu Woon (played by an actor in yellowface). Virginia Ainsworth, an American actress, stars as Frinzi, a one-time member of a criminal gang in Chinatown who has turned a new leaf and makes a pact with police to track down the leader of the Chinese drug ring. The villains are eventually captured by a detective and reporter with the help of Grainger’s daughter, Jackie, and Frinzi. The film was made by a new production company, Juchau Films, and was not at all well received; as Eric Reade describes it, “the first and last Juchau Film swept across the screen like a spasm of nausea”. [35] A more recent film drawing on the tradition of German and Chinese villains is Gallagher’s Travels (Michael Caulfield, 1986), where an investigative journalist stumbles onto an animal-smuggling operation involving a German mastermind and a Chinese triad.

In addition to the short films of this decade, a feature film which most clearly depicts the Chinese as a thieving race (in the context of the Goldrush) is Phillip K. Walsh’s infamous The Birth of White Australia (1928). The film attempts to portray a panoramic “history” of the early white settlement of Australia similar to D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (USA 1915) in the American context. Walsh constructs this history around a series of sequences that portray key events in the nation’s early (white settler) life, including Captain Cook’s landing at Botany Bay, a performance by Dame Nellie Melba, speeches by former Prime Ministers, and the Duke of York’s opening of the first Federal parliament in Canberra in 1927 (some of these events, including the latter, are shown using actuality footage). The most significant structuring event, in terms of screen time and significance accorded to it, is the discovery of gold at Lambing Flat (now Young) in New South Wales and the subsequent race riots on the goldfields between Australian and Chinese miners in 1860-1861.

The film was made while the White Australia Policy was in full effect, and in fact the origins of the policy can be traced to the Gold Rush period of the 1850s and 1860s, with white miners’ resentment towards industrious Chinese prospectors culminating in violence on the Buckland River in Victoria and at Lambing Flat in New South Wales. In response, the governments of these two colonies introduced restrictions on Chinese immigration, and by 1890 all states had legislation to preserve the purity of White Australia, with Alfred Deakin’s support. Deakin, a leader of the federation movement, believed that the Japanese and Chinese might be a threat to the newly formed federation, leading to his support for legislation that would ensure they were kept out: “It is not the bad qualities, but the good qualities of these alien races that make them so dangerous to us. It is their inexhaustible energy, their power of applying themselves to new tasks, their endurance and low standard of living that make them such competitors”. [36]

The Immigration Restriction Act 1901, the key instrument of the White Australia Policy, received royal assent on 23 December 1901. [37] The paranoia, fear and confusion encapsulated by the Act and policy are apparent on the surface of The Birth of White Australia. From the opening intertitle, which contains the following Forward, the historical mood and sentiment are barely concealed:

The founders of Australian Nationhood defined its boundaries within the Empire, and framed its constitution in white nationality. In 1854 the Prologue to Australia’s greatest Epic began. In that year our fathers wrought to stem the on-rushing tide of Asiatics which threatened the submergence of the white race in this country.

Of all the films discussed so far, The Birth of White Australia is the most forthright in expressing the sentiment that Australia forged its national identity (a white national identity) through “stemming the tide” of immigration from its Asian neighbours. [38] Newspaper articles of the time echo this general feeling, including the following from the Sydney Morning Herald in 1928: “The title [of the film] rises from the anti-Chinese riots of the ‘sixties, when the diggers came into conflict with the police as a result of so many Chinese causing difficulties with the claims and otherwise making themselves objectionable to Australian sentiment.” [39]

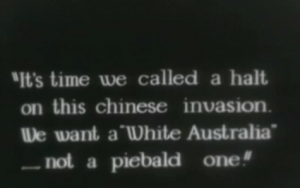

The recreation of the Lambing Flat incident used local (amateur) actors; “Whites were recruited to play Chinese, with stockings over their faces to suggest Mongoloid features.” (p. 191) The Chinese are portrayed as dirty, thieving, cunning characters with pigtails and long beards. In comparison, the white prospectors are given names, personalised, and shown with their loving families. When a white woman comes across a group of Chinese and tells them that they should not wash their clothes in the shared drinking water, the Chinese attack her. Shop signs display “Oriental Hotel” and “Oriental Bank”, signifying the extent to which it was perceived that the “Orientals” had taken over the town. Angry crowds respond by rioting, “We want a White Australia, not a piebald one. These Asiatics have polluted the water, jumped our claims and stolen our gold”. Similar arguments about “crushing hordes” and “floods” of Asians continue today. Throughout the film, sympathy for Aboriginal characters is mobilised simultaneously as hatred against the Chinese is gathered. [40] Nevertheless, as Liz Niven notes, what is also elided from the film is the fact that the film “shows no remorse in suggesting that the birth of white Australia required the death of black Australia.” [41]

The film, which was financed by investors from the New South Wales town of Young, had a private screening in Sydney in July 1928, followed by a public opening at the Strand Theatre in Young on 5 September 1928. There were no other commercial screenings held in any of Australia’s capital cities. Tom O’Regan suggests that the fact that the film was so unsuccessful (outside Young) means that “the film’s place on the Australian social imaginary was limited”. [42] Nevertheless, and despite the film’s lack of distribution during its day, I would argue that the film remains significant (socially, culturally and historically) for the rift it portrayed between (white) Australia and its Asian population. It has endured as a significant part of Australia’s film history (featuring on Australian Screen, the National Film and Sound Archives online, and in key academic texts such as Tom O’Regan’s Australian National Cinema), albeit controversially.

In recent years the film has screened at the Pordenone silent film festival in Italy in 1994, which was the first time an Australian film was showcased at the event. [43] This screening has added to the film’s controversy and notoriety. [44] As Siew Keng Chua writes:

The film has set the boundaries of the discourse against which subsequent Australian films with Asian, particularly Southeast Asian, settings and characters are delined … The study of Australian films must deal with the analysis of this film just as the study of American films must engage with Griffith’s Birth of a Nation. Whereas the latter contains aesthetic and technical innovations of interest to film scholars, the former is technically and aesthetically irredeemable. Nevertheless, the film is historically important in locating one (extreme) set of the hierarchy of orientalist discourses in Australian films. [45]

This film, however unsavoury, provides yet another aspect to the modernity of Australian cinema created through a distinction from Asia (although in this case aligned both to the British Empire and to American nationhood through the Griffith homage). Australia’s “modernity”, as portrayed in the film, is also placed in an international context through its reception, from its screening at the respected Pordenone silent film festival to an international audience.

The Wife and Lover

The historical reality of the early period of Australia’s settlement meant that while there was a population of Asian (mostly Chinese) men in Australia as part of the Gold Rush, Asian women were not resident in any significant numbers. Interracial relationships between whites and Asians were not a feature of early silent films although they have become a dominant structuring device in Australian cinema featuring Asian characters from World War II to the present day. There are several contemporary examples of this romantic configuration, especially between white men and Asian women, including The Home Song Stories (Tony Ayres, 2007), Heaven’s Burning (Craig Lahiff, 1997), Priscilla: Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliot, 1994), Aya (Solrun Hoass, 1991), and Arigato Baby (Greg Lynch, 1990). Less often, Australian films have featured relationships between Asian men and white women, as in Japanese Story (Sue Brooks, 2003), The Goddess of 1967 (Clara Law, 2000), Little Fish (Rowan Woods, 2005), and Mao’s Last Dancer (Bruce Beresford, 2009). [46]

These interracial relationships and tropes of Asian men and women are not the main focus of this essay although they are worth noting for the significant role they play in Australian cinema today, in particular as filmic responses to Australian-Asian relations following World War II and the Vietnam War. [47] Interestingly, a rare portrayal of an interracial relationship in a film preceding the 1920s is between an Aboriginal man, detective Jimmy Cook (played by boxer Sandy McVea), and a Chinese woman in The Enemy Within (Roland Stavely, 1918). The film, a tale of espionage in Sydney, was made in an environment of fear and mistrust following World War I. McVea’s character has a supporting role to the film’s hero, Jack Airlie, played by stuntman Reg ‘Snowy’ Baker. This hierarchical triangulation of colonial, indigenous, and Asian relations and representational politics adds another layer of complexity to the representation of Asian character types as ‘tokens’ or marginal characters.

An often-discussed example of the gendering of Asian women in contemporary Australian filmmaking through tokenisation is the character of Cynthia in The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert. Priscilla, Aya, and Arigato Baby take on the figure of the mail order bride (in the former example), and the war bride (in the latter two examples), both of which have become representative of a particular form of sexualisation of Asian women. Kathryn Robinson notes that “the mail-order bride has become a potent symbol in Australian representations of Asia” and that Priscilla “created a character who encapsulated one dimension of the stereotype: a sex-crazed, manipulative ex-bar girl who had tricked a decent, outback Aussie battler into marrying her”. [48] Despite reflecting only a minute proportion of the actual population, stereotypes persist and take on a life of their own with these characters still functioning as tokens of exchange mediating the cinematic portrayal of inter-racial relationships into the present day.

It is important to note that the use of the term “stereotype” in this paper is not inherently value-laden; that is, stereotypes are not necessarily “bad”, or “good”, exaggerated or reductive though they may be. To return to the original meaning of the word “stereotype” derived from its function in the printing press, stereotypes are more about (mechanical) duplication, repetition and imitation. Following this original meaning, I am more concerned with the function of stereotypes as “representational device[s], a possible tactic of aesthetic and political intervention in situations in which the deployment of stereotypes by dominant political or cultural discourses has long been a fact”. [49] As Rey Chow argues, the stereotype is “an objective, normative practice that is regularly adopted for collective purposes of control and management … and not merely as a subjective, devious state of mind.” [50] My aim in this essay has been to begin to question just how and what these stereotypes duplicate and imitate; only then is it possible to assess their representational significance. The examples that have been highlighted in this essay have been chosen precisely because they are stereotypes, and therefore perform a functional element in the films. Beyond value judgments placed on interracial relations, the function these stereotypes carry out are in the service of building an Australian national identity, not only against the British or American, but also against Australia’s newly prominent Asian neighbours.

Conclusion

I began this essay with William D. Routt’s argument that placed Australian films of the 1920s in the context of international film modernisms. Drawing inspiration from Routt’s discussion of how Australian national identity sprung from the desire to forge a cinematic distinction from Great Britain, my aim was to address the obvious neglect and omission of any discussion in early Australian film history and scholarship about Asian characters in the period of Australian silent cinema. It is my argument that this neglect has in fact contributed to the “coming of age” or modernity of Australian cinema in a way that was as important as Australia distinguishing itself from both British and American cinematic influences, whether artistic, populist, or otherwise. Marginal Asian characters have functioned, and continue to function, as tokens of exchange mediating these other dominant relationships.

Due to space constraints, this essay has only focused on the representation of “Asianness” and Asian characters in Australian cinema from the time of its inception through to the 1920s. The period leading up to World War II, which marks the appearance of propaganda films such as Indonesia Calling (Joris Ivens, 1946) and A Yank in Australia (Alfred Goulding, 1942), requires further and more detailed attention. Another contentious issue, which has only been gestured towards in this essay, is that of yellowface performance, which, although well documented in American film and theatre, remains under-researched in the Australian context. The films of the 1920s readily deployed yellowface performances, however yellowface has also continued (in spite of politically correct objections) into films such as A Yank in Australia where the director himself, Alfred Goulding, plays a Japanese spy in his own farce about a group of American newspaper reporters who become stranded off the Queensland coast when their cruise ship is torpedoed. Perhaps the most well-known example of yellowface in contemporary Australian cinema is Linda Hunt’s Oscar-winning portrayal of the male, dwarf photographer Billy Kwan in Peter Weir’s The Year of Living Dangerously (1982). These continuities, remaining unbroken and uncomplicated from the earliest period of Australian cinema, demonstrate that there is still a long way to go when it comes to the portrayal of Asian characters and their relationship to the “rest of Australia” in Australian cinema. It is hoped that the future of Australian cinema will not trade on these tokens alone but will find new ways of representing change, and exchange, between Asian characters and other, more dominant, notions of Australianness.

[1] See William D. Routt, “‘Shall We Jazz?’ Modernism in Australian Films of the ‘20s”, Senses of Cinema, 2000, http://archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/00/9/jazz.html.

[2] Routt

[3] Routt

[4] The four films of the 1920s which Routt mentions as containing the most obvious elements of stylistic modernism are Environment (Gerald M. Hayle, 1927); The Kid Stakes (Tal Ordell, 1927); The Spirit of Gallipoli (Keith Gategood, William Green, 1928), and Painted Daughters (F. Stuart-Whyte, 1925).

[5] Routt

[6] Routt

[7] Aboriginal Australians are missing from this equation but deserve more than a cursory mention in the short space allowed by this article. An interesting example that posits a relationship between Asians and indigenous Australians is the Chinese lover of the Aboriginal detective (played by Sandy McVea) in The Enemy Within (Roland Stavely, 1918). As with token Asian characters, however, these Aboriginal actors were not given main roles but supported the leading stars. For more on Aboriginal/Asian connections and relations in the cinema, theatre and in the sociological field, see Felicity Collins and Therese Davis, Australian Cinema After Mabo (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004); Jacqueline Lo, “Staging Asian-Indigenous History in Northern Australia”, Amerasia Journal 36:2 (2010): 50-61; and Peta Stephenson, The Outsiders Within: Telling Australia’s Indigenous-Asian Story (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2007), respectively.

[8] Routt

[9] By ‘Asian characters’ I am referring predominantly to East Asian nationalities and ethnicities such as the Japanese and the Chinese. In early Australian cinema, much of the representation was of Chinese characters in reflection of Gold Rush era immigration.

[10] Charles Tait’s The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906) is considered the first full-length feature film made in Australia. Some notable titles of the 1910s include The Squatter’s Daughter (Bert Bailey, 1910), The Hayseeds films (Beaumont Smith, 1917-1918) and The Sentimental Bloke (Raymond Longford, 1919).

[11] Eric Reade, Australian Silent Films: A Pictorial History of Silent Films from 1896 to 1929 (Melbourne: Lansdown Press, 1970), 90.

[12] Drawing on this film’s title are the World War II propaganda films: Japan’s Calling Australia, followed by Australia’s Indonesia Calling (Joris Ivens, 1946).

[13] Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film: 1900-1977 (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1980), 50. Further references to this text appear as page numbers in brackets.

[14] Graham Shirley and Brian Adams, Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years (Angus & Robertson Publishers and Currency Press: 1983), 32.

[15] Eric Reade, History and Heartburn: the Saga of Australian Film, 1896-1978 (East Brunswick, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1979), 10.

[16] Reade, History and Heartburn, 18.

[17] See also Shirley and Adams: “The title and also the publicity–particularly after a temporary ban by the police–could leave few in doubt that Satan was part of the wicked city itself and to be found specifically within its Chinese community.” (51).

[18] The White Australia Policy refers to the historical policies that sought to restrict non-white immigration to Australia from 1901 to 1973. The inauguration of White Australia as government policy is generally taken to be the passage of the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901. The Whitlam government abolished this policy through a series of amendments from 1973 culminating in the passing of the Commonwealth Racial Discrimination Act 1975, which made racially-based selection criteria for any official purpose illegal. The Policy will be discussed in greater detail in a later section on The Birth of White Australia.

[19] Shirley and Adams, 52.

[20] Shirley and Adams, 44.

[21] Conrad Hamann, “Heralds of Free Enterprise: Australian Cinemas and their Architecture from the 1900s to the 1940s”, in James Sabine, ed., A Century of Australian Cinema (Melbourne: Mandarin, 1995), 88.

[22] Reade, Australian Silent Films, 143.

[23] The Report by the Royal Commission was completed in March 1928 and recommended, among other things, that a quota be established for feature films made in Empire countries; for a Board of Censors to be established; and for increased tariffs on foreign films. These recommendations were not put into effect; nevertheless production was stimulated for a short while in anticipation of government action, with 1928 being the most productive year for Australian feature films in a decade. Towards the end of the decade, however, production again tapered off with technological and financial barriers associated with producing films in sound, and when it became apparent the Royal Commission was not going to bring about any change. Pike and Cooper, 116.

[24] For example, Eric Reade’s remarkably comprehensive survey of Australia’s silent film does not mention any Asian characters in the films that feature them.

[25] http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/1214892/Indigenous-tokenism-an-empty-gesture.

[26] http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2010/03/15/2845954.htm.

[27] See Janice D. Yoder, “Rethinking Tokenism: Looking Beyond Numbers”, Gender and Society 5:2, June 1991, 178-192. See also Gail M. Nomura, “Significant Lives: Asia and Asian Americans in the History of the U.S. West”, The Western Historical Quarterly, 25:1 (Spring 1994): 69-88. Nomura notes that whereas significance is ascribed to European American settlers, people of colour must achieve it (69).

[28] Dana L. Cloud, “Hegemony or Concordance? The Rhetoric of Tokenism in ‘Oprah’ Winfrey’s Rags-to-Riches Biography”, Critical Studies in Mass Communication (1996) 13, 115-137, 123.

[29] Shirley and Adams, 59.

[30] Anna Gardner, “A Girl of the Bush: Representations of Rural Women in Australian Silent and Early Sound Film”, http://www.pleasantfluff.com/2009/07/30/a-girl-of-the-bush/.

[31] Gardner.

[32] Gardner.

[33] Deb Verhoeven, “Sheep’s Clothing: A dress in some Australian films”, in Ken Berryman, ed., Screening The Past: Aspects of Early Australian Film (Acton, ACT: NFSA, 1995), 153.

[34] Graeme Turner, National Fictions: Literature, Film, and the Construction of Australian Narrative, Sydney: Allen& Unwin, 1986, 98.

[35] Reade, History and Heartburn, 64.

[36] Kay Schaffer Manne, “Generation: White Nation Responses to the Stolen Generation Report”, Australian Humanities Review, June 2001, http://www.lib.latrobe.edu.au/AHR/archive/Issue-June-2001/schaffer.html.

[37] Under the Act, the main device used to exclude non-Europeans was a dictation test held in any European language nominated by an immigration officer. It was initially proposed that the test would be in English, but it was argued that this could discourage European migration and advantage Japanese and African Americans. From 1932 the Dictation Test could be given during the first five years of residence, and any number of times. The Test was administered 805 times in 1902-1903 with 46 people passing, and 554 times in 1904-09, with only six people successful. After 1909 no person passed the Dictation Test and people who failed were refused entry or deported. The Act, frequently amended, remained in force until 1958. National Archives of Australia, Documenting a Democracy, Immigration Restriction Act 1901, http://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/item.asp?sdID=87#significance.

[38] Note: Chinese migration to Australia still allowed despite the White Australia policy being in place because of the importance of Chinese labour and expertise to certain parts of the Australian economy. Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema (London: Routledge, 1996), 348.

[39] Sydney Morning Herald, “The Birth of White Australia”, Wednesday 25 July, 1928, p. 9, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1301&dat=19280725&id=8ogQAAAAIBAJ&sjid=mZUDAAAAIBAJ&pg=4139,6373728.

[40] O’Regan, 348.

[41] Liz McNiven, “Secondary Curator’s Notes”, Australian Screen Online, National Film and Sound Archive, http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/birth-of-white-australia/notes/. The film contains some archival footage of indigenous Australians, including footage of an Aboriginal man at the opening of Parliament House in Canberra in 1927, named in the intertitle as King Billy.

[42] O’Regan, 327.

[43] O’Regan, 346.

[44] “Imagine if this film could talk. What would the dialogue be like? If the intertitles are any indication, I am sure most Australians today would prefer to render the film silent again.” McNiven.

[45] Siew Keng Chua, “Reel Neighbourly: the Construction of Southeast Asian Subjectivities”, Media Information Australia 70 (November 1993):29; 28-33; original emphasis.

[46] See Olivia Khoo, “Telling Stories: The Sacrificial Asian in Australian Cinema”, Journal of Intercultural Studies 27: 1-2 (2006): 45-63, and Belinda Smaill, “Intercultural Romance and Australian Cinema: Asia and Australia in The Home Song Stories and Mao’s Last Dancer”, Screening the Past, Issue 28, 2010, http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue/28/intercultural-romance-and-australian-cinema.

[47] For example, in films such as The Enemy Within (Roland Stavely, 1918),[/ref]

[48] Kathryn Robinson, “Of Mail-Order Brides and ‘Boys’ Own’ Tales: Representations of Asian-Australian Marriages”, Feminist Review 52, Spring 1996, 53.

[49]Rey Chow, “Brushes with the-Other-as-Face: Stereotyping and Cross-Ethnic Representation”, in The Protestant Ethnic and the Spirit of Capitalism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 54.

[50] Chow, 54.