To date, filmmaker Walter Hill has received relatively little scholarly attention – this, despite Michael J. Anderson’s contention that “the director’s exceptionally rich first decade of productivity” constitutes “one of the finest of any American filmmaker” of the New Hollywood generation. [1] On those occasions when he is singled out for critical attention (usually of the journalistic as opposed to academic variety), the focus tends to be on Hill’s directorial facility for crafting elegant and economical action sequences. Consider, for example, Philip French’s characteristic description of Hill as “one of the most distinctive action-movie directors Hollywood has produced, an exponent of the lyrical violence in the class of Sam Peckinpah.” [2] The historical comparison with Peckinpah, an acknowledged influence on Hill, is certainly appropriate. In films such as Hard Times (1975), Hill’s directorial debut, The Long Riders (1980), Hill’s first Western, and 48 Hrs. (1982), his breakthrough box office success, the echoes of Peckinpah’s “lean, terse, unsentimental” cinema are not difficult to detect. [3] What has heretofore been less remarked on, however, is another, equally important and distinctive element of Hill’s filmmaking aesthetic, especially in evidence in his early work: the director’s postmodern sensibility. One sees this in the clean, studied minimalism of The Driver (1978), in which a nameless, nearly wordless getaway driver and the cop trying to catch him play cat-and-mouse on the gleaming, night-soaked streets of Los Angeles; one feels it in the pulsing kineticism and hallucinatory vision of The Warriors (1979), a surreal, comic book-influenced reworking of Xenophon’s Anabasis chronicling the titular street gang’s nighttime odyssey through a hellish New York City. Hill’s propensity for cinematic postmodernism would find its fullest expression a few years later, in 1984’s Streets of Fire, a film that in some ways marks both the culmination of, and the beginning of the end for, the director’s postmodern impulses. An odd and generically hybrid text billing itself as “A Rock & Roll Fable,” Streets of Fire is difficult to categorize or even describe – perhaps M. Keith Booker’s assessment of Pulp Fiction (1984) might serve as the most accurate characterization of Hill’s movie as well: “the film gleefully combine[s] various periods, genres, and styles, producing the perfect postmodern cinematic stew.” [4] Considering this affinity between Tarantino’s work (which includes intertextual homages to The Driver) and Hill’s, it would not be unreasonable to expect Walter Hill’s name to pop up in discussions about prominent postmodern filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s: Tarantino; David Lynch, whose Blue Velvet came out two years after Streets of Fire and similarly blurs the temporal boundaries between the 1950s and the 1980s; the Coen Brothers, and so on. And yet, thus far, Hill’s name has been conspicuously absent from any such critical considerations. In this essay I seek to redress this oversight by closely examining the postmodern contours of Streets of Fire, in particular the text’s playful destabilization of temporal, generic, and stylistic borders, and exploring how the film illustrates some of the attendant hazards of operating within a postmodernist cinematic aesthetic (including but not limited to a Jamesonian weakening of historicity).

Streets of Fire tells the story of Tom Cody (Michael Paré), an ex-soldier who is compelled to return home to an unnamed city and rescue his old girlfriend, the famous singer Ellen Aim (Diane Lane), after she is abducted by Raven Shaddock (Willem Dafoe), the menacing leader of a biker gang called The Bombers. In crafting the tale, Hill claims he was hoping to make “what I would have thought was a perfect movie when I was in my teens,” [5] which led him to fill the text with things he believed “were great then and which I still have great affection for: custom cars, kissing in the rain, neon, trains in the night, high-speed pursuit, rumbles, rock stars, motorcycles, jokes in tough situations, leather jackets and questions of honor.” [6] Assuming that Hill did not actually engage in all that many rumbles or high-speed pursuits as a teenager, one can conclude with a fair degree of confidence that at least some of the entries on this list represent not real-life experiences or memories, but rather cinematic ones – filmic images that deeply ingrained themselves into Hill’s teenage psyche, and which he later sought to resurrect in his own work. This suspicion is seemingly confirmed by the sheer number of film genres evoked by Streets of Fire, among them musicals, neo-noir, science fiction, “troubled teen” pictures like Rebel Without a Cause (1955), biker flicks, and Westerns. Nor are movies Hill’s only intertextual reference point in the film. As Hill’s co-screenwriter Larry Gross explains, the director wanted Streets of Fire to feature the hero of a comic book, but he couldn’t find any comics he wanted to adapt; consequently, Hill instead tried to create “his own ‘comic book’ movie, without the source material actually being a comic book.” [7] This makes the text, at least in part, a Baudrillardian simulacrum: a copy with no original. In light of these attempts by Hill to recuperate and revitalize the formative artistic tropes and imagery of his youth, Streets of Fire could aptly be labeled a “nostalgia film,” a term developed by Fredric Jameson to describe movies that tend to lose themselves “in mesmerized fascination in lavish images of specific generational pasts,” [8] and in which – as elaborated by Booker – filmmakers seemingly “regard the styles of the past as a sort of aesthetic cafeteria from whose menu they can nostalgically pick and choose without concern for the historical context in which those styles originally arose.” [9] And indeed, Hill picks and chooses with abandon in Streets of Fire, melding stylistic and generic features in strange and sometimes startling ways. Even Larry Gross was forced to take note of the eccentric nature of the emerging film partway through the production, confessing to Walter Hill five weeks into the shoot, “This movie is somewhat weirder than we thought.” [10]

If Larry Gross found himself surprised by the unanticipated weirdness of Streets of Fire, upon the film’s release the largely hostile critical community found itself struggling to classify what it had just seen, often resorting to the strategy of triangulating Hill’s text between two better known and more readily categorizable works. For example, in The New York Times, Janet Maslin saw Hill’s movie as lying “between The Wild One and Blade Runner.” [11] For Jay Scott, in The Globe and Mail, the film was at times “like Raiders of the Lost Ark chasing The Warriors,” at others times “like Flashdance crossed with Rumble Fish.” [12] And David Chute, writing for Film Comment, positioned the film as an effort to cross “a rock opera” with “a Howard Hawks horse opera.” [13] The reference to Hawks here is instructive: reviewers invoked the Western more than any other genre in their discussions of the film, and several drew direct parallels to the works of Howard Hawks. However, I would argue that the crucial figure to be mindful of when approaching Hill’s text is not Hawks (although, as will be addressed below, his legacy does exert some influence on the story’s conclusion) but rather John Ford. Brian Salisbury, reappraising Streets of Fire in 2016, touched on this creative kinship between Hill and Ford when he characterized the film, in yet another critical coupling, as “The Warriors meets The Searchers.” [14] It is a particularly fitting description, when one considers the many correspondences in narrative structure and characterization that Hill’s movie shares with Ford’s 1956 masterpiece. In fact, these correspondences are so extensive, Hill’s text might be most productively thought of as a kind of postmodern reworking or adaptation of Ford’s film. A comparative look at both works should help to illustrate this point.

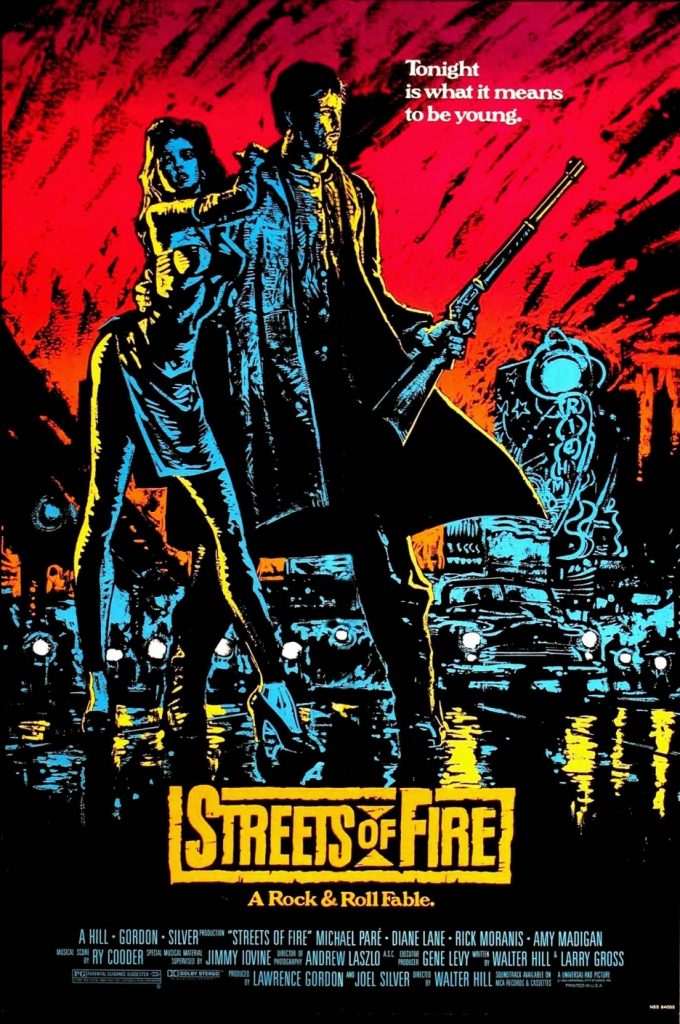

The Searchers tells the story of Ethan Edwards (John Wayne), a former Confederate soldier returning home several years after the end of the Civil War to be reunited with his brother and his brother’s family in Texas. In the words of Edward Buscombe, Ethan is “recalcitrant, maybe a renegade; surly and suspicious, he seems to have something to hide.” [15] This “something to hide” may be a crime Ethan has committed, as the two sacks of freshly minted “Yankee dollars” in his saddle bags seem to suggest. When Ethan is questioned by Captain Clayton (Ward Bond) as to whether he is a wanted man, and why he was absent from the surrender to Union forces three years prior, Ethan is defiant, refusing to admit or deny his guilt, and telling the captain, “[I] don’t believe in surrenders … No, I’ve still got my saber … didn’t beat it into no plowshare neither.” Tom Cody, the more youthful protagonist of Streets of Fire, evinces a similar mixture of truculence and fierce independence. An ex-soldier and veteran of distant unnamed wars, wars in which he “didn’t get no medal,” Tom returns to his home city to be reunited with his sister, and brings with him an aura of the renegade/outlaw not dissimilar to Ethan’s. As the local police note upon his arrival, Tom has “always been a real badass … he belongs in jail with all the other juvenile delinquents.” Tom certainly plays the part, brandishing a six-shooter and the kind of old fashioned Winchester rifle favored by Ethan, and his long, Western-style coat would not look out of place on the Texas plains. But of course, beneath the veneer of disreputability, behind the loner ethos, Tom, like Ethan, harbors a deep and abiding fidelity – not to the law or the nation, but to his loved ones. And it is this shared fidelity, ultimately, that drives both men to undertake a daunting challenge: a rescue mission deep in the heart of hostile terrain.

Ethan’s journey begins when his nieces, Lucy (Pippa Scott) and Debbie (played as a child by Lana Wood and a teenager by Natalie Wood), are kidnapped by a band of Comanches that have raided the home of his brother Aaron (Walter Coy), murdering the rest of the family. Lucy soon turns up dead as well, and Ethan sets out to find Debbie, no matter how many years it takes or how far he has to search. Along the way, Ethan discovers that Debbie was taken by Scar (played improbably by Jeffrey Hunter), a ferocious Comanche chief who, Buscombe argues, comes to function in the text as Ethan’s “unconscious, his id if you like.” [16] That is, during his raid on the homestead of Ethan’s brother , Scar rapes and subsequently kills Aaron’s wife Martha (Dorothy Jordan), with whom Ethan is secretly in love; for Buscombe, then, by raping Martha, Scar has effectively “acted out in brutal fashion the illicit desire” Ethan fosters in his heart. [17] As a result, Scar and Ethan become, in a sense, mirror-images, with Ethan’s “self-righteousness” in his pursuit of the Comanche chief representing an “attempt to blot out his own guilt.” [18] Ethan is aided in his quest by Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), a family friend with Native American heritage (he claims to be one-eighth Cherokee), which makes the racist Ethan regard him – at least initially – with suspicion, as indicated by his first words in the film to Martin: “A fella could mistake you for a half-breed.” Martin proves himself to be a worthy sidekick, in the end, helping Ethan track Scar down in a territory called the Seven Fingers of Brazos, where Martin himself kills Scar during Debbie’s rescue. Ethan demonstrates his own capacity for savagery by subsequently scalping Scar’s dead body, and although Martin worries that Ethan might actually try to kill Debbie rather than save her, “tainted” as she is by her years of living with the Comanche, Ethan instead delivers her to the safety of the Jorgensen ranch before wandering off, alone again, into the dusty Texas countryside.

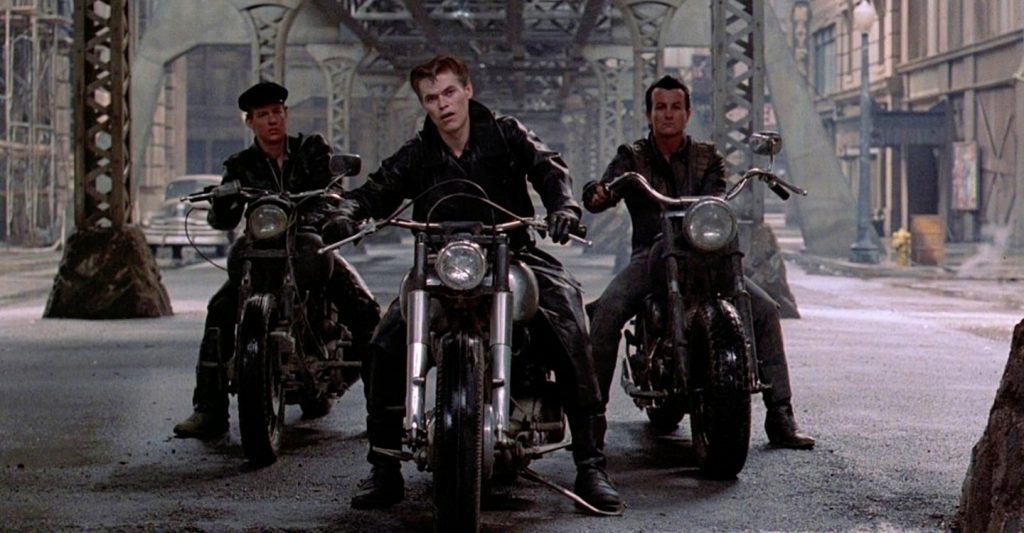

For Tom Cody, the journey starts with the abduction of Ellen Aim, an ex-girlfriend whom Tom appears to alternately love and hate, as Ethan vacillates between loving and hating Debbie. Ellen is also taken by a band of “savages,” although in this case the marauders wear leather jackets in lieu of war paint, and ride motorcycles instead of horses. The leader of the motorcycle gang, The Bombers, is Raven Shaddock, and we are introduced to Raven in the same way we are introduced to Scar in The Searchers: in close-up, a face emerging ominously from the shadows, Scar’s headdress replaced by an impossibly high pompadour framing Raven’s scowling features. With his manicured look and wardrobe comprised of “angular strips of latex and leather,” Raven cuts an androgynous figure, standing in direct counterpoint to Tom’s overtly macho appearance and bearing – and yet, by acting out Tom’s “illicit desire” for his forbidden love, now in a relationship with another man, by acting on the impulses that Tom must repress and claiming Ellen as his own, Raven comes to embody Tom’s “unconscious” mirror-image, just as Scar came to embody Ethan’s. [19] Tom vows to find and confront Raven, and bring Ellen home, and he reluctantly lets a sidekick, McCoy (Amy Madigan), join him in his effort. McCoy’s role in Streets of Fire was originally written for a man, and Hill did little to change the part after casting Madigan: McCoy dresses like a man, spouts “tough guy” dialogue like a man, and forecloses any possibility of sexual tension between herself and Tom by informing him bluntly during their first encounter, “You’re not my type.” McCoy, then, shares Raven’s androgyny, and blurs the border(s) between genders in a manner analogous to the “half-breed” Martin’s blurring of racial borders. Team assembled, Tom is tipped off to Raven’s whereabouts by an eccentric, oddball minor character , Ben Gunn, performed by Ed Begley, Jr. (in The Searchers, Ethan is tipped off to Scar’s location by Hank Warden’s comical character Mose, whom Buscombe situates within “a long tradition of Fordian oddities, drunks and simpletons”). [20] Raven is holding Ellen in a dangerous part of the city called “The Battery,” and Tom organizes a raid on Raven’s hideout that is choreographed much like Ethan’s raid into the Seven Fingers of Brazos: bullets flying, motorcycles (as opposed to horses) flipping forward as if hitting tripwires, people running about in chaos. Unlike Scar in The Searchers, Raven survives this raid, and later travels to Tom and the now rescued Ellen’s neighborhood, “The Richmond,” where he challenges Tom to a duel using enormous coal hammers – likely an homage to the swordfights found in Akira Kurosawa’s samurai films, which Hill counts as an influence on his work. Tom defeats Raven but lets him live (in the screenplay Tom kills Raven with a knife, bringing to mind Ethan’s scalping of Scar), and the heavily armed residents join together to finally drive The Bombers out of The Richmond for good, in a moment that – as Michael J. Anderson observes – owes more to Hawks than John Ford, reprising as it does “the social vision of Howard Hawks’s supreme masterwork, Rio Bravo (1959), with the community coming to the individual’s aid.” [21] With the threat to said community and civilized values vanquished, Tom, who no more belongs within respectable society than Ethan Edwards, gets in his convertible and speeds away from the city he helped save, into the neon horizon.

These striking parallels in narrative and characterization between The Searchers and Streets of Fire (and others like them I have not mentioned), along with the intertextual tips of the cap to Kurosawa and Hawks and all of the additional filmic references enumerated by reviewers, indicate a degree of self-awareness in Hill’s work that is characteristic – even constitutive – of cinematic postmodernism. That is to say, Streets of Fire is very much a movie about other movies, a film about film history, and as such it lends credence to Jean Baudrillard’s notion that contemporary cinema is a medium that constantly “plagiarizes itself, recopies itself, remakes its classics, retroactivates its original myths … the cinema is fascinated by itself as a lost object.” [22] It is important to note, though, that the referential touchstones of Streets of Fire are not strictly limited to cinematic works: as alluded to above, Hill also drew inspiration from comic books in conceiving the overall design of the film, and in places the text self-consciously adopts the visual grammar of music videos, an emerging art form at the time of the movie’s release. The aesthetic ambitions of Streets of Fire, therefore, are both self-reflexive and intermedial. This dynamic, almost compulsive intertextuality mobilized by the film can make for an unexpectedly beguiling spectatorial experience – knowing viewers, tipping to the movie’s aesthetic agenda, find themselves searching its glossy, neon-bright surfaces for the echoes and fragments of other works, other mediums; endeavoring to identify the myriad ways in which Hill’s text is appropriating and repurposing – or, to use the language of hip hop, which like music videos was coming into its own as a new form of creative expression in the 1980s, sampling and remixing – certain stylistic and generic markers of the past. Differently put, trying to spot and decode each of Streets of Fire‘s intertextual “riffs,” as it were, becomes half of the moviegoing fun. But this dizzying mélange of prior artistic forms and contents can have a disorienting effect on audience members as well, as screenings I have organized for my students have shown me. By consciously denying viewers the kind of spatial and temporal coordinates they have been conditioned to expect from more conventionally realistic modes of filmmaking, Streets of Fire risks – indeed, practically seems to court – spectator confusion and a consequential lack of meaningful identification with its characters, and the film even opens itself up to accusations that it partakes in the postmodern “weakening of historicity” famously propounded by Fredric Jameson. [23] Again, a brief comparison of Streets of Fire and The Searchers should be helpful in clarifying this idea.

The Searchers is, by and large, a work of cinematic realism, and it grounds itself in a very particular time and place: Texas 1868, as one of the film’s opening title cards tells us. This conveys to the attentive viewer certain information. We are in the Reconstruction era, after the Civil War, when Texas was being reintegrated into the Union, against the wishes of some of its more independent-minded denizens; it is a period marked by a “violent struggle for supremacy over southern Texas” between settlers and Native Americans, a struggle that would culminate in the bloody Red River War of 1874-5, which “finally destroyed the Comanche’s military strength”; it is a juncture in our nation’s history where the open enmity between races ran wide and deep. [24] Information such as this is useful to the viewer in better understanding the narrative that is about to unfold, and the motivations of the characters within it, and it gives the story a concrete historical foundation that Jameson finds to be sorely lacking in postmodern texts. For Jameson, that is, works of postmodernism “no longer set out to represent the historical past” [25] ; instead, they exhibit a sort of atemporality in which “the past as ‘referent’ finds itself gradually bracketed, and then effaced altogether,” leaving us rooted not in some semblance of historical reality, but rather amidst a welter of antecedent images and surfaces and endless intertextual play. [26] Certainly, this is where Streets of Fire positions the audience – in “Another Place, Another Time,” a title card informs us, bereft of any discernible geographic or temporal indicators that would help us to locate ourselves in an identifiable city or year. The unnamed urban “place” in which the action unfolds resembles, at times, Chicago, with its elevated trains rumbling ambiently in the background, but a Chicago made strange and vaguely futuristic, bathed in constant rain and a neon sheen that would prompt critics to label the city a sci-fi dystopia and draw comparisons to the ersatz Los Angeles of Blade Runner (1982). Within this metropolis, several time periods evidently coexist at once. Tom Cody, as mentioned, favors an old-fashioned six-shooter and Winchester rifle, and shots of whiskey are paid for by tossing a few coins on the bar. Messages are sent via telegraph, and, as Katie Rife points out, the streets are stuffed with “such classic symbols of midcentury Americana as Studebakers, corner diners, and black leather motorcycle jackets.” [27] The 1950s, in fact, which Jameson perceives to be “the privileged lost object of desire” for American society, haunt this filmic world – yet all of the trappings of the era are magnified, intensified, exaggerated as in a dream or half-forgotten memory (see, in example, the profusion of gravity-defying pompadours). [28] The 1980s also make their presence felt, through sartorial flourishes and video-jukeboxes and, most especially, the music. According to Jake Cole, the sound of the film is achieved by fusing “’80s arena rock” with “its 1950s roots,” resulting in such notable musical moments as “a rockabilly band tear[ing] through its numbers with punk speed, saxophones howling over triple-time shuffles, and a doo-wop group croon[ing] against programmed beats with a similar blend of organic swing and highly processed rhythms that [Morris Day’s band] the Time were using around the same period.” [29] Far from aspiring to the type of historical specificity sought for in The Searchers, then, Streets of Fire purposefully, brazenly blurs the spatial and temporal boundaries which might have otherwise anchored viewers, and articulates a cinematic vision that, untethered from any commitment to historicity, gleefully embraces and blends America’s cultural past, present and future.

This postmodern aesthetic, Jameson argues, this basking in playful and dialogic intertextuality in lieu of striving for historical authenticity, comes with a price: what he calls “a new kind of flatness or depthlessness, a new kind of superficiality.” [30] In cinematic terms, this manifests itself in films distinguished not by their emotional or historical depths, but by their shiny surfaces, “the glossy qualities of the image[s]” [31] – works in which actors seem to be performing “allusions to much older roles” as opposed to embodying living, breathing, fully-rounded human beings. [32] A handful of critics detected this latter trait in Streets of Fire. David Chute, for example, dubbed the text’s three main characters – Tom Cody, McCoy, and Ellen Aim – “bubble-gum cartoons of classic movie types: The Loner, The Sidekick, The Goil,” [33] and Odie Henderson intuited a kinship between Michael Paré’s Tom and the onscreen persona of John Wayne. [34] The defiant swagger and tough guy mien adopted by Paré in the film do indeed owe a debt to some of Wayne’s more iconic performances, but it is worth noting how differently audiences respond to a character like Ethan Edwards than Tom Cody. Ethan, we come to see over the course of The Searchers, is a product of a specific moment in the history of the United States: scarred by the horrors of the Civil War and (we presume) the violent frontier struggles against increasingly displaced Native American tribes, Ethan is a paradox, a contradiction – a man loyal to his family, but disloyal to his nation; a man of bravery, but also of savagery; a man capable of great heroism, and of repellent bigotry; a man riven by love and hate, protective of his community, but never at peace within it; a man, in the end, forged in the crucible of his times. So rich a character is Ethan Edwards, Buscombe tells us, so harrowing is his journey, it is difficult to watch the closing image of Ford’s film – in which Ethan, having rescued Debbie, cradles his elbow in a wounded gesture and then turns and walks alone into the desolate plains of Texas, the door to home closing slowly behind him – without “feel[ing] Ethan’s tragedy.” [35] Tom Cody, on the other hand, has never been accused of being a tragic figure, or eliciting the same sort of spectatorial investment as Ethan Edwards. A man outside of history, Tom is less a creation of sociopolitical forces than textual concerns: as Hill explains, when conceiving of the character, he wanted Tom (as incarnated by Paré) to be “movie-heroic in acting style” and “cowboy-cliché in dialogue.” [36] In other words, Hill intended for Tom to function as what Jameson would refer to as “a ‘connotator’ of the past,” a vehicle for evoking memories of prior cinematic texts from another place, another time. [37] And, it must be said, Hill is largely successful in his goal … perhaps too successful. When watching Tom Cody onscreen, it is difficult to relate to him as anything other than a walking, talking movie reference – a character in quotation marks. From his expressionless Bronson-esque glare to his Eastwood-like growl to his Wayne-inspired affect, Tom is all surface, a celluloid shell beneath which it is difficult to divine even the slightest hint of vulnerability, or emotional complexity, or a genuine beating heart. [38] We understand his motives, to be sure, and his actions and reactions are the engine driving the narrative forward, but Tom never really becomes more than a filmic chess piece in Hill’s hands, never proves himself worthy of our identification rather than simply our dispassionate fascination. Unlike Ethan Edwards, whose pain serves as a palpable reminder of very real historical traumas, Tom remains, in the final analysis, nothing more and nothing less than a cinematic expression of, and vessel for, pure postmodern nostalgia.

Of course, such nostalgia is a large part of the appeal of Streets of Fire, for receptive audience members and (judging from Hill’s own comments) the film’s creator himself. Whatever the limitations of operating within the obsessively self-reflexive postmodern mode of filmmaking exhibited by the text, it does have its concomitant and compensatory rewards, among them the pleasures of revisiting previous aesthetic experiences and eras, pleasures that would lead critics like Katie Rife and Philip French to label Streets of Fire and its movie-minded agenda an instance of “pure cinema.” [39] But nostalgia is a double-edged sword, and even the most ostensibly lighthearted return to the cultural past can be accompanied by disquieting consequences. Consider, for example, the racial undertones to Hill’s film: The Sorels, a 1950s-style African-American doo-wop group whom Tom Cody and Ellen Aim meet during their escape from The Battery, find themselves at times facing 1950-style racism, as they are called “spade musicians” by an abusive police office (which is viewed within the diegesis as troubling) and fall under the sway of a controlling, obnoxious white music promoter (which is not). Or look at the text’s treatment of women, which Janet Maslin called misogynistic in her review of the movie: women in Streets of Fire are addressed variously as “skirt,” “honey” and “sweetie-pie,” and Tom Cody freely admits that he initially broke up with Ellen because he was threatened by her burgeoning career. [40] In fact, Tom, just like a protagonist in an old Western, appears to regard his “damsel-in-distress” more as a trophy to wrestle and fight over than an equal, and he thinks nothing of – under the guise of protecting Ellen by preventing her from following him on a dangerous mission – knocking her out cold with a punch to the jaw. Or one could examine the film’s queer politics: how the androgynous Raven’s final banishment from “decent” society, along with the gender-bending McCoy’s admission in the story’s closing moments that she once had a boyfriend, evidently foreclose less “traditional” sexual avenues for the characters and reinforce the community’s heteronormative standards. Collectively, then, all of these disturbing elements in Streets of Fire indicate that Hill’s nostalgic postmodern vision, whatever its intent, is neither uncomplicated nor unproblematic – which, in turn, prompts a question. Is Hill’s text, whether deliberately or inadvertently, reinscribing certain retrograde attitudes and tropes attendant to the preceding artistic forms/contents it is appropriating, or is the film subverting said attitudes and tropes by effecting an ironic distance from them, thus engaging in what Linda Hutcheon would characterize as “a critical revisiting, an ironic dialogue with the past” in light of the present? [41] The answer to this query is not readily clear. In places, through its exaggerated, tongue-in-cheek tone, Streets of Fire does indeed seem to be mounting the brand of de-doxifying postmodern critique that Hutcheon theorized; in other places, however, especially in its handling of female characters, the movie strikes one as more reactionary, earning Odie Henderson’s accusation that it sometimes resembles a chauvinistic “teenage male fantasy.” [42] So, perhaps the most accurate response, and certainly the most postmodern, is to say that Streets of Fire is at once progressive and retrogressive, making it something of an “incoherent text,” to borrow a phrase from Robin Wood – a work that destabilizes as it re-instantiates, elucidates as it frustrates, entrances as it estranges. [43]

STREETS OF FIRE, Michael Pare, 1984

It is difficult to determine if this ideological incoherence played a role in the film’s critical and box office failure. What is easier to conclude, though, is that this failure had a dramatic impact on the directorial style of Walter Hill going forward. After the text’s fairly disastrous reception, Hill beat an aesthetic retreat, and has never again attempted anything quite so audacious, quite so daringly idiosyncratic as he did in Streets of Fire. Movies like Another 48 Hrs. (1990), Geronimo: An American Legend (1993), and Wild Bill (1995) have continued to showcase Hill’s considerable skill in fashioning taut, dynamic action scenes, but generally gone are the postmodern concerns and ambitions marking much of his early work. The relative absence of such postmodernist experimentation in his recent output may explain why Hill is regularly overlooked in critical discussions about consequential postmodern filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s; but if academics tend to ignore or discount Hill’s influence on subsequent generations of directors, the filmmakers themselves do not. Postmodern-oriented auteurs ranging from Quentin Tarantino to Nicolas Winding Refn to Edgar Wright have all praised Hill’s early movies, and have paid intertextual tribute to them in their own films. Larry Gross, screenwriter and occasional Hill collaborator, also detects the director’s imprint on texts like Robocop (1987) and Se7en (1995), which he maintains are “completely saturated in the iconography” of Streets of Fire [44] . And one could even argue that there is a lineal connection between Streets of Fire, with its comic book-inspired visual design, and the contemporary spate of graphic novel adaptations typified by Sin City (2005) and The Spirit (2008). In other words, Streets of Fire, along with The Driver, The Warriors, and Southern Comfort (1981), Hill’s allegorical re-envisioning of the Vietnam War set in the Louisiana bayou, comprise a complex postmodernist body of work that has exerted a forceful pull on a host of succeeding films and filmmakers, even if it has largely escaped scholarly attention. This essay, I hope, has been a first step toward addressing this academic omission, one which will generate additional (re)appraisals of Walter Hill’s oeuvre, and spur further (re)examinations of Hill’s thoroughly postmodern vision, thereby forging for Hill the place within critical discourse that he so richly deserves.

Notes:

[1] Michael J. Anderson, “Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire (1984) & the Dystopian Recursion of the 1950,” Tativille, August 30, 2011, http://tativille.blogspot.com/2011/08/walter-hills-streets-of-fire-1984.html.

[2] Philip French, “Streets of Fire,” TheGuardian.com, January 11, 2014, https://www.the guardian.com/film/2014/jan/12/streets-of-fire-philip-french-classic-dvd.

[3] French, “Streets of Fire.”

[4] M. Keith Booker, Postmodern Hollywood (Westport: Praeger, 2007), p. 48.

[5] Quoted in David Chute, “Dead End Streets,” Film Comment 20, no. 4 (1984): pp. 55-58.

[6] Quoted in “Streets of Fire,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, July 9, 2018, https://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/Streets_of_Fire.

[7] Quoted in Blake Harris, “How Did This Get Made: A Conversation with ‘Streets of Fire’ Co-Writer Larry Gross,” /Film, January 26, 2016, https://www.slashfilm.com/streets-of-fire-oral-history/.

[8] Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991): p. 296.

[9] Booker, Postmodern Hollywood, p. xviii.

[10] Quoted in Harris, “How Did This Get Made.”

[11] Janet Maslin, “Screen: ‘Streets of Fire,'” The New York Times, June 1, 1984, https://www. nytimes.com/1984 /06/01/movies/screen-streets-of-fire.html.

[12] Jay Scott, “The Hybrid Streets of Mire,” The Globe and Mail, June1, 1984.

[13] Chute, “Dead End Streets,” p. 55.

[14] Brian Salisbury, “In Another Time, It Found Its Place: Revisiting Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire,” Film School Rejects, December 16, 2016, https://filmschoolrejects.com/in-another-time-it-

found-its-place-revisiting-walter-hills-streets-of-fire-5771698bac46/.

[15] Edward Buscombe, The Searchers (London: BFI Publishing, 2003): p. 9.

[16] Buscombe, The Searchers, p. 21.

[17] Buscombe, The Searchers, p. 21.

[18] Buscombe, The Searchers, p. 21.

[19] Jake Cole, “Streets of Fire,” Slant Magazine, May 17, 2017, https://www.slantmagazine.com /dvd/review/streets-of-fire.

[20] Buscombe, The Searchers, p. 62.

[21] Anderson, “Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire.”

[22] Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994): p. 47; emphasis in original.

[23] Jameson, Postmodernism, p. 6.

[24] Buscombe, The Searchers, pp.13-14.

[25] Jameson, Postmodernism, p. 25.

[26] Jameson, Postmodernism, p. 18.

[27] Katie Rife, “For Pure 80s-Meets-50s Rock’n’Roll Aesthetics, It’s Hard to Top Streets of Fire,” The A.V. Club, April 19, 2018, https://film.avclub.com/for-pure-80s-meets-50s-rock-n-roll-aesthetics-its-hard-1825309742.

[28] Jameson, Postmodernism, p. 19.

[29] Cole, “Streets of Fire.”

[30] Jameson, Postmodernism, p. 9.

[31] Jameson, Postmodernism, p. 19.

[32] Jameson, Postmodernism, p. 20.

[33] Chute, “Dead End Streets.”

[34] Odie Henderson, “Tonight Is What It Means To Be Young: ‘Streets of Fire’ at 30,”

Rogerebert.com, October 1, 2014, https://www.rogerebert.com/balder-and-dash/tonight-is-what-it-means-to-be-young-streets-of-fire-at-30.

[35] Buscombe, The Searchers, p. 69.

[36] Quoted in French, “Streets of Fire.”

[37] Jameson,Postmodernism, p. 20.

[38] The only glimpse we actually get into Tom’s interior life is his memories of Ellen Aim, which take the form of black-and-white excerpts from a music video, indicating that his very psyche is perfused by/a product of visual imagery.

[39] Rife, “Pure 80s-Meets-50s”; French, “Streets of Fire.”

[40] Maslin, “Screen: ‘Streets of Fire.'”

[41] Linda Hutcheon, A Poetics of Postmodernism: History, Theory, Fiction (New York: Routledge, 1988): p. 4.

[42] Henderson, “Tonight.” It is worth noting that by design no character in the film is over thirty years old.

[43] Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 46.

[44] Quoted in Harris, “How Did This Get Made.”