Preface: Adrian Slattery died from cancer on 14 May 2016, at the age of 30. He wrote and submitted the following text as an Honours dissertation in Film & Screen Studies at Monash University in late 2011; I was the supervisor/advisor on his chosen – and highly unique – topic of Stoner films. Adrian (I well recall) was just as determined to master film genre theory (at Monash, he had imbibed Con Verevis’ wise teachings in this field) as he was to celebrate a type of pop movie he appreciated and loved – I can vividly imagine how excited he would have been by Harmony Korine’s criminally underrated The Beach Bum (2019)! He diligently tracked down every obscure movie title and bibliographic reference I threw at him; he was a winning mixture of provocative cheekiness and dogged dedication – traits with which I readily identified. He received a High Distinction (as assessed by my brilliant colleague, Dr Belinda Smaill) for the outstanding work he eventually produced. Adrian was truly beloved among the student cohort of his years at Monash, and everybody he encountered has fond memories of him; he held a special energy, gentle and powerful at once. In the years that followed his graduation, Adrian intermittently contacted me, eager to pursue the prospect of publishing his thesis in some modified form. His own path in the world of arts was not academic, but primarily music-related: as a singer and songwriter, Adrian was a leading figure in a vibrant community, working with the bands Major Major and Big Smoke, and – even while hospitalised – on his final project, Time is Golden. That album appeared publicly in 2019, thanks to his friends and collaborators. (A list of Adrian’s available recordings can be consulted at https://www.discogs.com/artist/2808478-Adrian-Slattery.) The thesis on Stoner films, however, remained in the shadows, until its cause was diligently taken up with me once more by members of Adrian’s family, his brother Ben and mother Anna. At last, after the pandemic freeze somewhat thawing, Screening the Past is able to present Adrian’s groundbreaking work, thereby honouring his legacy (and, indirectly, that of another recently deceased film scholar, Steve Neale), bringing to light this aspect of his creative and intellectual activity. His wife, Paige Clark (author of She is Haunted, Allen and Unwin, 2021), wrote in a recent, moving tribute for The Guardian (19 July 2021): “Adrian died in May 2016, just before his 31st birthday. I wrote in my notes that he had it easy because he did not have to deal with what came after his death. Hadn’t I helped him navigate what came next, and hadn’t he left me alone to figure it out myself? He hadn’t, because he had shown me what mattered: making art, making meaning and, ultimately, moving on past the things we can never even hope to overcome. He had done it himself, and I could do it too”.

– Adrian Martin, November 2021

I would like to stress the need for further research, further concrete and specific analyses, and for much more attention to be paid to genres hitherto neglected in genre studies.

– Steve Neale (1990: p. 66)

The Stoner film is commonly referred to and identified in popular film culture. However, there has been little to no academic enquiry made into theorising it as a genre. Drawing upon the popular recognition of this genre, I aim to interrogate its function in relation to genre theory in order to develop a framework for present and future academic discussion.

In his essay “Genre and Movies”, Douglas Pye states: “The misconception is to think of a genre as essentially definable and therefore of genre criticism as in need of defining criteria” (Pye 1975: p. 30). The subsequent history of genre theory in film studies has proven this to be true, as genre is now understood as a fluid process, operating on a number of levels simultaneously. Steve Neale, in Genre and Contemporary Hollywood, delineates the methods of approach to genres.

… from the point of view of the industry and its infrastructure, from the point of view of their aesthetic traditions, from the point of view of broader socio-cultural environment upon which they draw and into which they feed, and from the point of view of audience understanding and response. (Neale 2002: p. 2)

Here, I pool together key writings on the various elements most essential to genre theory – text, subject and industry – in order to explore and understand the Stoner genre in all its facets. First, at the level of the film text, the Stoner film’s textual and aesthetic conventions are analysed – in particular, the role marijuana plays in influencing and constructing notions of genre. Second, a subject or spectator approach will interrogate how audience desires and expectations impact the evolution and comprehension of the Stoner film. Finally, the Stoner film will be discussed in terms of industry orientations, demonstrating the underlying economy of genre production, and how concepts of genre are formulated and circulated by the industry. This multiple approach will support my secondary aim: to demonstrate how the study of genre contributes to a greater appreciation and understanding of films and the cinematic process as a whole.

I: TEXTUAL AND AESTHETIC CONVENTIONS

The discussion of a film genre begins with a discussion of films themselves. While genre simultaneously operates at the levels of text, industry and subject, the film-text itself is often where the initial recognition of a cinematic genre occurs. If genres are, as Dudley Andrew describes them in his book, Concepts in Film Theory, “specific equilibria balancing the desires of subjects and the machinery of the motion picture apparatus”, then the film provides a tangible site in which to stage this negotiation (Andrew 1984: p. 114). An analysis of a genre’s textual and aesthetic traditions is essential in establishing a foundation of physical filmic evidence from which an argument for a genre can be made.

Central to deciphering systems of genre operating within a body of films is the notion of genre conventions. Tom Ryall, in his article “Teaching Through Genre”, states that genres “may be defined as patterns/forms/styles/structures which transcend individual films, and which supervise both their construction by the film maker, and their reading by an audience” (Ryall 1975: 28). It is these identifiable “patterns/forms/styles/structures” that constitute a set of genre conventions. Similarly, both Pye and Rick Altman emphasise the recognition of conventions as fundamental to the theorisation of genre. In his article “Genre and Movies”, Pye is concerned with identifying relevant “tendencies” local to genres; these include specific and recurring instances of plot, narrative structure, character, time and space, iconography and themes (Pye 1975: p. 34). Developing this notion further in “A Semantic/Syntactic Approach to Film Genre”, Altman sees genre conventions as the interplay of semantic and syntactic elements, where “the semantic approach … stresses the genre’s building blocks, while the syntactic view privileges the structures into which they are arranged” (Altman 1984: p. 10). To Altman, a successful genre is one where “generic syntax … is reinforced numerous times by the syntactic patterns of individual texts”, further stating, “the genres that disappear the quickest are the ones that depend entirely on recurring semantic elements, never developing a stable syntax” (Altman 1984: p. 16).

In Hollywood Genres: Formulas, Filmmaking, and the Studio System, Thomas Schatz parallels this thought: “It is not their mere repetition which endows generic elements with a prior significance, but their repetition within a conventionalized formal, narrative, and thematic context” (Schatz 1981: p. 10). In light of this, a study of the aesthetic and textual conventions of a genre needs to address not only the visibly recurring elements in a body of films – characters, settings, icons – but also the meaningful systems in which they operate. A subsequent textual analysis of a selection of films commonly recognised as Stoner films will work towards identifying and discussing the conventions of the genre.

In their 2010 book, Reefer Movie Madness: the Ultimate Stoner Movie Guide, Shirley Halperin and Steve Bloom trawl through cinema history to provide an account of over 700 films in which drugs are featured. In selecting films for Reefer Movie Madness, Halperin and Bloom privileged those in which “marijuana or other drugs are central to the story, or the movie is particularly fun to watch stoned”, while also including movies where “marijuana is not essential to the plot but contain a key scene, or character that smokes, deals, or otherwise encourages its use” (Halperin 2010: p. 9).

While Reefer Movie Madness is comprehensive, it is too broad in its selection of movies, and it fails to distinguish between Stoner films and other types of drug films. Halperin and Bloom’s criterion of marijuana as being central to the story, however, highlights the key convention of the genre. In further agreement with this, Marisa Meltzer, in an article entitled “Leisure and Innocence: the Eternal Appeal of the Stoner Movie”, defines the Stoner film as “by, for, and about pot smokers”, specifying, “these are not movies where a lone joint is passed around in a party scene”. Instead, Meltzer argues, “the stoner film shows serious commitment to smoking and acquiring marijuana as a lifestyle choice” (Meltzer 2007).

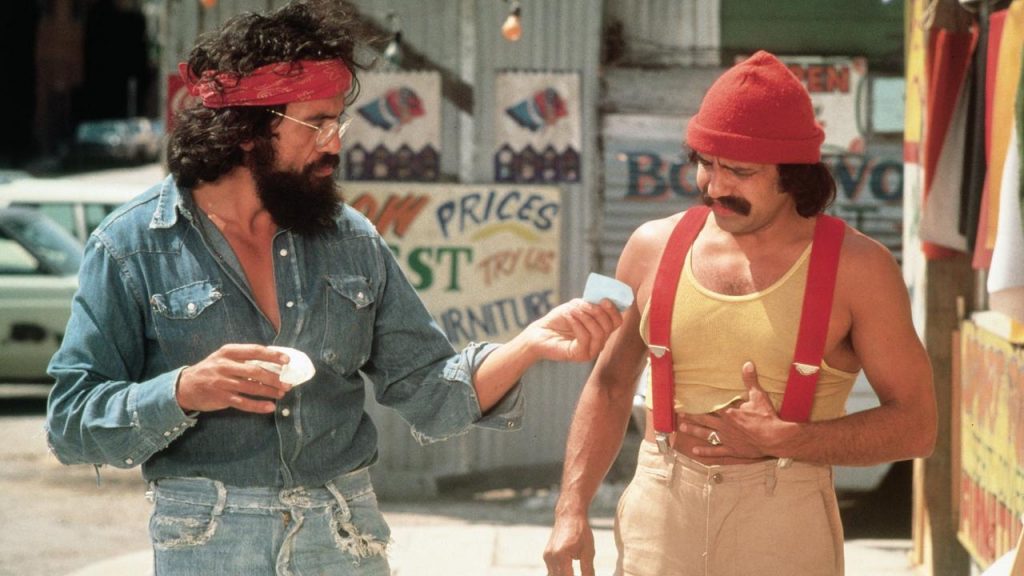

It is evident that the argument for the Stoner film in popular discussion differs slightly in each instance, depending on the importance of marijuana’s influence throughout the text – ranging from being foreground throughout an entire film to featuring in a scene or two. While differing criteria are unavoidable – Neale writes, “it is not possible to write about genres without being selective” (Neale 1990: p. 50) – there is one point of commonality among most discussions of the genre: Cheech Marin & Tommy Chong’s Up in Smoke (Lou Adler, USA, 1978) is considered the progenitor of the Stoner comedy.

The appearance of marijuana in film pre-dates Up in Smoke: a cowboy smoking the first on-screen joint in Notch Number One in 1924. In 1936, pot was the subject of Reefer Madness (directed by Louis J. Gasnier), an American propaganda-ridden, anti-drug film, subsequently championed by stoners for its overtly ludicrous portrayal of marijuana and its effects. Additionally, Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, USA, 1969) is a hallmark of drug cinema, but is lauded for its overall depiction of the late 1960s omni-drug-fuelled counter-culture rather than the specific use of marijuana (Halperin 2010: p. 6). It was Up in Smoke that first transported marijuana to the screen in its natural vehicle: comedy.

In his article, “Contact High: A Stoner’s Movie Journey from A to Z”, Christoph Huber refers to Cheech & Chong as “pioneering”, while Meltzer dubs them “the spiritual fathers of the genre” (Huber 2009: p. 30; Meltzer 2007). Halperin and Bloom also account for Up in Smoke, calling it “the first stoner comedy”, adding, “Cheech & Chong created the genre” (Halperin 2010: p. 7). There is some truth in these statements; a description of Cheech & Chong as the pioneering fathers and creators of the Stoner comedy genre is not to be taken lightly. In fact, a simple overview of the narrative structure of Up in Smoke reads like a formula for any modern day Stoner comedy: two dudes, lots of weed, ostensibly straight-forward objective, and crazy – funny – misadventures. The Stoner comedy, imbibed in the cinematic consciousness by Cheech and Chong, is the most readily identifiable instance of a Stoner film genre.

Why should the Stoner comedy be privileged as the poster child for the Stoner film? The answer lies in the analysis of the genre’s primary convention: marijuana.

Marijuana

Marijuana – cannabis, weed, pot, grass, herb, reefer, Mary Jane – is a rose with many other names, and to the stoner they all smell just as sweet. In the Stoner comedy, marijuana is the star of the show. In the conventional narrative film, the propulsion of the plot and story hinge on the notion of cause and effect (Bordwell 2008: p. 77). Marijuana, in its filmic incarnation, is all at once an icon, a prop and the primary agent of cause and effect – the motor of the story. It carries with it connotations of coolness, relaxation, psychedelia, paranoia and humour. An illegal substance it may be, but in film, and increasingly in society, it is represented as the good drug. When discussing marijuana in relation to the Stoner comedy, there are two aspects of its nature that are pivotal to the existence and appeal of the genre: comedy and acceptability.

While marijuana has a number of cultural connotations, my discussion is particularly interested in one: hilarity. There is a general awareness, and an overwhelming supply of cultural evidence, that suggests weed and comedy are intrinsically linked. In his article, “Why Marijuana Makes Things Funnier, Medically Speaking”, Jim Hamblin, MD, attempts to identify exactly how marijuana interacts with the human body to cause an inclination for laughter. According to Hamblin, the clinically listed effects the drug has on the body’s central nervous system are: confusion, disorientation, vertigo, attention disturbance, dissociation, euphoria, headache, insomnia, panic attack, hallucination, amnesia, anxiety, lethargy, malaise, depression, memory impairment, and paranoia; “hilarity”, Hamblin notes, is “not among them”. While no exact scientific link can be found between marijuana and laughter, Hamblin posits that as “marijuana elevates your entire mood and, [it] thereby, inclines you to laugh more”, describing the release of endorphins triggered by THC – tetrahydrocannabinol, the main psychoactive substance found in marijuana – as delivering the “same end result as when you exercise or fall in love” (Hamblin 2011). In other words, smoking pot can make a person feel good, and places them in the perfect mood for laughter.

Other drugs, however, can make one feel good also. Users of cocaine, ecstasy, heroin, etc., argue that, addictions aside, these drugs make them feel good. This is where the importance of marijuana’s widespread acceptability attributes to the persistence of a genre that celebrates the use of an illicit substance. Acceptability is not the same as legality, and the Stoner comedy – n fact, all pro-pot related media – embodies and perpetuates this dichotomy. While the acceptability of marijuana is not universal, it is perhaps telling that attitudes towards the drug both societal and legal, are most at ease in California, the home of Hollywood.

In his article, “A Definitive Guide to Stoner Comedies”, Bradford Evans attributes this increasing cultural acceptance to “a wave of 60s/70s nostalgia [and] the introduction of medical marijuana beginning with its legalization in California”. Evans also finds cause for the contemporary resurgence of the Stoner comedy, stating, “the filmmakers, writers, and actors who emerged to make the drug films of the 1990s and the following decade were the ones who grew up watching Cheech and Chong and the first wave of pothead flicks” (Evans 2011). Whatever the precise reason may be, the success and sustainability of the Stoner comedy is a testament to marijuana’s privileged position of cultural acceptability in comparison to other illegal drugs.

An analysis of a selection of Stoner comedies reveals marijuana’s function within the text and demonstrates how this preliminary understanding of the drug is perpetuated by the genre.

Weed Narrative

When Pedro (Cheech) and Man (Chong) first collide in Up in Smoke, they waste no time in lighting up a monster-sized joint and smoking themselves into oblivion. Marijuana has appeared and kick-started the motor of the story, precipitating the “series of actions on the parts of the characters” that follows (Bordwell 2008: p. 78). What ensues is a haphazard pursuit of the next high, with each attempt to acquire more weed resulting in light-hearted encounters with the law, eventually landing Pedro and Man in Mexico with a mission to drive a van constructed entirely of marijuana (unbeknownst to them) back across the American border. In a commentary on the DVD release of Up in Smoke, Marin calls this an “innocence abroad” narrative, explaining: “There is no plot, just watching these two cosmic characters in a state of being”. This “state of being” for Pedro and Man is a state of being stoned.

Huber identifies in the Stoner comedy narrative a tendency for “digression”, stating it is the “major operation principle” in the genre (Huber 2009: p. 27). Cannabis leads the plot naturally on a series on digressions from the main objective, yet these digressions are central to the films’ structure – more so than the objective – and what is described as “no plot” is in fact the conventional narrative design of the Stoner comedy. Originating on the stage, Cheech & Chong developed and performed much of what became Up in Smoke live in sketch comedy routines. These digressions in narrative, then, not only serve as a filmic representation of a stoned, distracted consciousness, but also enable the “skit-like nature of much weed cinema” (Huber 2009: p. 34).

In the simple pursuit of getting high, Pedro and Man narrowly escape a drug bust at a party, are deported to Mexico accidently, and finally wind up at a battle of the bands with a smoking van that gets everyone – law officers included – stoned. The way pot functions as a convention of the Stoner comedy can be explained using Altman’s semantic and syntactic approach: marijuana is the semantic element and its resulting narrative digressions contribute to the syntax of the genre. In Up in Smoke, marijuana propels Pedro and Man on their adventure – transporting them literally in a van made of weed – and enables them to win the battle of the bands while evading the authorities at every turn. Marijuana is the hero, conveying an approving representation of an illegal substance.

In Half Baked (Tamra Davis, USA, 1998), a New York quartet of pot smoking buddies have their stoner utopian lives capsized when Kenny (Harland Williams) is arrested for murdering a police horse during an innocent trip to the local store for munchies – stoner slang for an assortment of snacks. Having fed his entire munchies haul to the horse, it swiftly drops dead because this particular horse is diabetic. Branded a “cop-killer”, Kenny is thrown in a maximum security prison and forced to contend with constant threats to his personal safety. This does not sound like an upbeat tale on paper, but Half Baked is a Stoner comedy, and Kenny’s predicament is presented as anything but serious. Prison is a very real threat to many a stoner, yet even this is made light of, demonstrating marijuana’s conventional influence on the film.

Marijuana reveals itself as the motor of the story in Half Baked: weed landed Kenny in prison, weed will get him out. His pals, Thurgood (Dave Chappelle), Brian (Jim Breuer) and Scarface (Guillermo D’az), then commit to selling pot until they raise enough money to post Kenny’s bail. Although the criminal ramifications of smoking and selling weed underpin much of the narrative, the only real challenge to the pot-smoking way of life in Half Baked presents itself in the form of a woman. Having freed Kenny from jail, Thurgood arrives at a crossroads with his two loves – marijuana and his girlfriend, Mary Jane (Rachel True) – and must choose one or the other. Thurgood chooses the girl, stating, “She’s all the Mary Jane I’ll ever need”. Thurgood’s ultimate decision to continue a healthy relationship with a woman rather than get stoned with his buddies could represent a necessary maturation out of stonerism toward a more meaningful lifestyle. Mary Jane, however, is synonymous with marijuana, and Thurgood’s choice enables him to symbolically have both the girl and the drug.

![]()

In Gregg Araki’s Smiley Face (USA, 2007), marijuana functions as the cause of, and solution to, the main narrative events. The stoner protagonist, Jane (Anna Faris), wipes out her roommate’s cupcake batch in a frenzied attack of pot-induced hunger, only to discover they were in fact weed cupcakes. Now super-duper stoned, Jane arrives at the logical pothead solution to rectify this dilemma: buy more weed to make a new batch of cupcakes before her roommate finds out. In true Stoner comedy fashion, Jane’s objective is thrown off course as she botches her plan time and again, winding up on the run from the law with a stolen original manuscript of Karl Marx’s The Communist Manifesto in her clutches. Once again, it is the sum of a series of digressions that comprise the narrative. In a slight twist on the usual convention, marijuana does not end up ‘saving’ Jane. Her failure to rectify a single one of her many predicaments results in her picking up trash on the side of the highway, a punishment she is dealt as part of a criminal community service program.

Here, Araki presents a less favourable outcome for the pothead than most other Stoner comedies do. His treatment of Jane throughout the film, however, is encompassed by an attitude of complete endearment – she is even shown collecting trash with a smile on her face – and does not convey any hint that her lifestyle should be viewed as bad or illegal. Despite the less-than-desirable consequences Jane faces, Smiley Face is still largely a celebration of stonerism, rather than a warning against it.

Friday (F. Gary Gray, USA, 1995), set in the suburbs of Los Angeles, is certainly one of the more literal examples of Marin’s earlier commentary on Stoner comedies as having “no plot”. It is centred on two friends, Craig (Ice Cube) and Smokey (Chris Tucker), who sit on Craig’s front porch on a Friday and get high simply because, in Smokey’s words, they “ain’t got no job … and ain’t got shit to do!” Not inclined to leave the porch, the action in Friday comes to Craig and Smokey. A series of neighbourhood friends, acquaintances and enemies all stop by to create and expand the narrative.

Friday exemplifies Stoner comedy’s tendency to confine its story to a limited space and time. As its title suggests, the events in Friday transpire over a single day, and are contained within a highly localised setting. Similarly, Smiley Face, Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle (Danny Leiner, USA, 2004), and Dude, Where’s My Car? (Leiner, USA, 2000), all take place in a single day (or night), and in the local setting of a single suburb or town. While not explicitly set in a single place or time, even films such as Up in Smoke, Half Baked, How High (Jesse [son of Bob] Dylan, USA, 2001), and Pineapple Express (David Gordon Green, USA, 2008), are all confined in either one aspect or the other. It is common for films to reduce story time, condensing the plot, whether days, months, or years, into a manageable 90 minutes of screen time (Bordwell 1985: p. 83). The Stoner comedy tends to operate on the lower end of this scale, leaning closer to equivalence among story, plot and screen time.

This recurring characteristic of the genre is yet another example of the films’ continual dialogue with marijuana and its associated stoner culture. The limited scope of space and time in the Stoner comedy is representative of the stereotypical nature of the stoner as existing in the moment and not being one to venture outside local boundaries – or even get off the couch, for that matter. The films use these local settings and short stretches of time to provide a familiar platform from which a stoner adventure can then be launched, whether it is a seemingly innocuous burger run, or a struggle to recollect where a car was left the night before.

Weed Form

Not only does marijuana influence the Stoner comedy in terms of its narrative conventions, it also affords the genre a freedom of form. Through an acknowledgement of marijuana’s associated side-effects and its inherent relationship with the psychedelic, the Stoner comedy employs the cinematic medium to materialise an essence of being stoned. Half Baked provides an example of marijuana’s ability to trigger such formal aspects, playing off its psychedelic qualities. In a scene where Thurgood brings home some top-grade medical marijuana for the gang to try, they get so high they literally begin to float up off the floor and proceed out the window for a flying tour of New York; Scarface’s dog also gets a blast of the weed later in the film and takes to the sky. In Friday, after Smokey gets Craig high, the camera shifts to Craig’s direct point of view, framing Smokey in close up with a joint hanging out of his mouth. As Smokey stares down the lens inquisitively, the camera renders his movements with a slight delay, creating a blurry out-of-time effect, coupled with a heavy reverb on his voice. The audio and visual elements of this scene combine to portray the overall lethargic and distanced experience of being stoned. In How High, when Silas (Method Mann) and Jamal (Redman) smoke weed laced with the ashes of their dead friend Ivory (Chuck Deezy), he promptly appears as a luminous semi-transparent apparition, assisting them with their college exams.

While most Stoner comedies feature only a handful of these formal interjections in their otherwise unchallenged style of continuity editing, Smiley Face provides the most complete example of the genre’s narrative and formal conventions operating at their full potential. The narrative of Smiley Face is focalised through the incredibly stoned psyche of Jane, and draws upon the effects produced by marijuana on her brain in an attempt to construct a formal representation of being stoned. Side effects such as dissociation, hallucination and memory impairment are evident in the film’s style. In a scene where Jane is sitting in front of her computer formulating a plan to replace her roommate’s cupcakes, her inner thoughts are communicated through voice-over narration of her own actions. Jane’s inner-self is dictating the plan while her outer-self responds visually – an example of the dissociative effect of marijuana. The shot of her in front of the computer then cuts to an entirely black frame that represents the computer screen, as her voice-over instructions appear as typed text on the frame, “1. buy more pot”. As she continues typing out the plan, the type appears slowly and is often backspaced for correction or deleted entirely as she begins to digress and forget where it is headed. Jane acknowledges this in the narration as the words disappear, “that’s not really part of the plan, scratch that”. This cutting between the type on a black frame and a mid-close up of Jane intently listening to her own narration, coupled with the visual and audible negations of her own thought process, further enhance the formal communication of Jane’s state of mind. The scene then closes with a hazily filtered fantasy of Jane as a 1950s portrait of domestic perfection, removing the freshly baked cupcakes from the oven with a beaming smile on her face, depicting her hallucination of the ideal end to the plan.

This scene is just one example of the way marijuana influences form in Smiley Face, yet the whole film characterises a movement through the stoned experience, transitioning between moments of paranoia, confusion, delusion, disorientation, euphoria and hallucination. Smiley Face not only etches a stoner’s journey physically through its narrative, but also psychologically through its form.

The above examples demonstrate marijuana’s affect on film form internally – its distinct deployment within a film’s shots and scenes, such as through characters’ subjective experiences – however, it can also inform film style externally. Up in Smoke utilises this alternate level of weed-inspired film style with its overall haphazard production. The pacing and selection of shots, as well as the acting and setup of the mise en sc?ne, all give off the impression of not only low-budget filmmaking, but also evince a lethargic, somewhat nonchalant style – a stoned aesthetic. Marin concedes this on the DVD commentary for Up in Smoke, stating: “Our naivete works really well for us … There [were] a lot of instances where it was good we didn’t know what a close-up was”. Cheech and director Adler go on to concur that their production methods – or lack thereof – created “a different rhythm” compared to other, faster-cut comedies. Whereas Smiley Face is intentional in its formal navigation of a stoned experience, Up in Smoke owes its stoned aesthetic largely to its unintentional – or na•ve – process of production.

The recognition of marijuana as a convention of the Stoner genre then informs its appearance in other, non-Stoner films. In John Hughes’ The Breakfast Club (USA, 1985), the tension between the characters in detention is broken with the passing of a joint. The Breakfast Club is a high school film, dealing with issues surrounding youth and identity, yet the introduction of marijuana removes the walls separating the different characters and unifies them, if only for a moment. Informed by the conventions of the Stoner comedy, this scene in The Breakfast Club transforms the tense, stuffy library into a cool, relaxed and light-hearted environment. Upon smoking a joint, the nerd becomes cool, the pretty girl sees the ridiculousness of being popular, the bad boy relaxes and drops his hateful facade, and the restrained, conservative jock lets loose with one of the craziest solo dance routines captured on film. The scene even concludes with a hallucinatory moment as Andrew, the jock, screams at the climax of his dance, the sheer power of his voice shattering the glass on the library door.

Returning to Meltzer’s statement that Stoner films should be “by, for, and about pot smokers”, an analysis of how the pot smoker is understood and represented in cinema further supports the argument for the Stoner comedy as a valid cinematic genre. This reveals the next principle convention of the Stoner comedy: the stoner him- or herself.

The Stoner

American cinema has a long-held tradition of creating and celebrating cinematic archetypes/stereotypes. The cowboy, the gangster, the detective, the vampire and the zombie are just a small selection of stock character types that perpetually cycle through the cinematic consciousness. In the study of genres, character types such as these are given their significance and meaning through a continually evolving representation in their respective parent genres. Barry Keith Grant, author of Film Genre: from Iconography to Ideology, writes, “In genre movies characters are more often recognisable types rather than psychologically complex characters” (Grant 2007: p. 17). Through the decades following Up in Smoke, the stoner has cemented its place as a veritable type in the canon.

To discuss the features that comprise the stoner, it is helpful to counter-pose it against an esteemed and long established cinematic type: the cowboy. A cowboy is visually iconic with his hat, boots and pistol. The stoner is a visual icon too, favouring long hair, loose threads and a pipe – signifiers of the counter-culture from which it was born. ‘The Dude’ (Jeff Bridges), the protagonist from The Big Lebowski (1998), is an example of the true embodiment of the stoner. Dressed in a raggedy grey bathrobe and sporting a dishevelled mop of long brown hair, The Dude wanders the aisles of the corner store, his flip-flops slapping against the floor while he peers out over his dark sunglasses. This first sighting of The Dude in The Big Lebowski provides the visual cues to his stoner nature.

The Dude, however, is more than just his attire. He walks to a beat entirely his own in the Los Angeles suburbs – the stoner’s natural habitat – and his being is more mythical than real, signified by his alias. Robert Warshow, in an article entitled, “Movie Chronicle: The Westerner”, describes the cowboy as “par excellence a man of leisure. Even when he wears the badge of a marshal or, more rarely, owns a ranch, he appears to be unemployed” (Warshow 1954: p. 192). The Dude is a genuine “man of leisure” if there ever was one; his life consists of getting high, bowling, driving around and “the occasional acid flashback”. When the real Big Lebowski, Jeffrey (David Huddleston), offended by The Dude’s crude appearance, quizzes him, “Are you employed, sir?” The Dude seems genuinely surprised by the question, exclaiming, “Employed?” as if it were a foreign concept. This is reminiscent of canonical stoner, Jeff Spicoli (Sean Penn), in the high-school comedy, Fast Times at Ridgemont High (Amy Heckerling, USA, 1982) – when asked by a friend, “Why don’t you get a job, Spicoli? You need money”, he replies, “All I need are some tasty waves, a cool buzz, and I’m fine”.

The Dude flouts conventional lifestyle; work, money and the law are merely obstacles in the way of his preferred existence. He is only roused from his world of stoner bliss through a case of mistaken identity, when a group of thugs looking for The Big Lebowski wrongfully attack him and urinate on his rug. Even then, The Dude’s main concern is his rug, because according to him it “really tied the room together”. The Dude champions the spirit of stonerism, portraying the mythical qualities of this contemporary archetype of the screen.

The stoner also exudes strong characteristics of individualism and self-reliance – features that herald the free, heroic, American spirit. The stoner carves out its own swath through the modern world, paying little mind to the rules and laws that govern Western capitalist society – laws that are seen to oppress the spirit of the common people – and exacts only what he or she needs to keep coasting on a high. Like the cowboy, the stoner is often at odds with the law and exists not necessarily outside of the law, but within one that is entirely his or her own. The stoner is a vigilante – a true anti-hero of the cinema.

This distrust of authority is reflected in many Stoner comedies, often parodying officers of the law as bumbling fools, such as the stooge-like detective squad in Up in Smoke, or the big, dumb, racist Officer Palumbo (Sandy Jobin Bevans) in Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle. In fact, after Harold (John Cho) is wrongfully arrested in Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle, Kumar (Kal Penn) displays complete disregard for the law and busts Harold out of jail, stating his reason to his friend, “I’m fucking starving! I figured I’d bust you out and we’d go get some burgers”.

The film stoner cannot truly exist in reality; neither can the cowboy, yet archetypes like these are constructed not of “inherited ideas” from the real world but from “inherited possibilities of ideas” audiences can recognise and aspire to (Jung 1989: p. 116, emphasis added). In a moment of poignancy, The Dude explains his and essentially all stoners’ existence, stating simply, “The Dude abides”.

The stoner is also distinct in his or her irrepressible urge to get high and remain so. Though this may seem ignoble, it is in fact the opposite – this high is not only a form of inebriation to the stoner, it also ensures the continual flow of positivity the stoner exudes in the world around him or her. In an article entitled, “In Praise of the Stoner, a True American Hero”, Stephen Hoban (2011) writes, “If the stoner is honest and true in pursuit of getting high, all will be well. The stoner always maintains integrity. Hence, we have stoner comedies; there are no stoner tragedies”.

Although promulgated chiefly by the Stoner comedy, the stoner is not rigid in that single instance of genre. Like other recognisable character types, the stoner carries the meanings and traits inherited from the Stoner comedy into all other filmic appearances, whether they are central or peripheral – from the aforementioned Spicoli to Donny (David Gallagher) in the action/science-fiction movie Super 8 (J.J. Abrams, USA, 2011).

Stoners, Dudes and Bromance

Owing to its dominant comic element, the Stoner comedy can be subversive, offering meaningful insight on issues such as law and order, gender, relationships and ethnicity. In fact, the genre takes comedy’s ability to explore taboo subjects one step further: its very existence is taboo. It is the Stoner comedy’s method of showing and not telling that allows it to function as witness of the real, providing the potential for critical engagement with these issues. At the heart of this dialogue is the stoner – the focal point through which these issues can be articulated.

While not evoking a wholly “male” mode (take due note the presence of female directors including Tamra Davis and Penelope Spheeris, as well as an overtly queer filmmaker like Araki), the Stoner comedy is placed in the realm of dude cinema – a non-gender-specific term that usually, however, connotes the masculine. A quick glance at the canon of cinematic stoners – Cheech, Chong, Spicoli, Smokey, Thurgood, The Dude, Harold, Kumar, etc – reveals a completely male-dominated role, with the only exception being Jane from Smiley Face. Not only is the Stoner comedy primarily a vehicle for male narratives, it is almost always a shared experience among men – a buddy story. The stoner has thrived in pairs since Cheech & Chong in Up in Smoke, yet the buddy system of the Stoner comedy differs to the regular comedy-coupling of straight man and crazy man – because no stoner is ever straight.

The stoner pairing then evolves the traditionally simple comic interplay of the buddy film into a portrait of contemporary male heterosexual relationships. The stoner, however, is neither ‘boy’ nor ‘man’ in any traditional sense, yet his nature, values and place in society lean more towards the former. In his article, “Dude, Where’s My Gender? Contemporary Teen Comedies and New Forms of American Masculinity”, David Greven describes boy culture as “a distinct cultural world, with its own rituals and its own symbols and values … separate both from the domestic world of women, girls, and small children, and from the public world of men and commerce … In this privileged space of their own, boys [are] able to play outside the rules of the home and the marketplace” (Greven 2002: p. 15). Operating in this space between domesticity and commerce, the stoner depends on his intimate relationships – predominantly with other stoners – to satisfy a meaningful existence without familial or professional aspirations. Unlike the cowboy, the stoner is not a loner. Stoner comedies emphasise the importance of these relationships, with strong themes of friendship underpinning the narrative.

Pineapple Express portrays the developing relationship between a stoner, Dale (Seth Rogen), and his pot dealer, Saul (James Franco). Negotiating the boundary between consumer and supplier – or smoker and dealer – Pineapple Express plays out the complexity of overcoming these labels, rendering an endearing depiction of stoner friendship and humanity. This male hetero love-fest is defined in the contemporary filmic landscape as bromance. Colin Carman describes this phenomenon in his article, “Bromance Flix and the State of Dudedom”, stating that “unlike the traditional buddy film, the bromance shows us that straight guys … can bond almost as strongly as heterosexual lovebirds” (Carman 2010: p. 50).

While not limited only to Stoner comedy, the notion of bromance is important nonetheless – for every stoner needs a friend. Bromance exists in the realm of what Greven calls the homosocial, “the relationships and spaces in which both male power and intimacy are concentrated”. However, he is quick to point out that “homosocial relations may include homosexual ones, but, in our homophobic culture, they are not meant to” (Greven 2002: p. 15). Though homosexuality is often acknowledged in the Stoner comedy, it is usually for comic effect, treated unseriously. In Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle, when Harold is knocked out fantasising about his dream-girl, Maria (Paula Garcés), he wakes up in shock and disgust to Kumar licking the side of his face. Kumar explains his actions: “You’ve been out cold for the past half an hour. I figured maybe if I did some gay shit, you’d wake up”.

As nearly all filmic evidence suggests, the stoner is a heterosexual male. So where, then, is the female located in relation to the stoner and the Stoner Comedy? Female characters are often relegated to the sidelines, most often present as objects of desire, harking back to the traditional “masculine perspective [that] was an inextricable part of the [Hollywood] genre system” (Grant 2007: p. 80). Maria in Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle, Debbie (Nia Long) in Friday, Mary Jane in Half Baked, Angie (Amber Heard) in Pineapple Express, and Lauren (Lark Voorhies) & Jamie (Essence Atkins) in How High, are all the most prominent female characters in their respective films, yet their presence is required only to reinforce their stoner male counterparts’ heterosexuality, through their limited interactions together. The females in these films cannot compete with the stoner bromance and fail to form any meaningful on-screen relationships. These characters are not necessarily treated unfairly in the Stoner comedy – they are not degraded or ridiculed – they are simply not really treated in any sense at all.

Smiley Face attempts to rectify this, casting a female in the lead stoner role. In all her stoner glory, however, Jane loses her femininity entirely, swallowed up by the overwhelmingly masculine nature of the stoner figure. Barry Keith Grant recognises this dilemma, stating, “By simply plugging women and others into roles traditionally reserved for men”, films are “prone to fall into the trap of repeating the same objectionable values” (Grant 2007: p. 82). Dissimilar to other film stoners, Jane is without a buddy and struggles in her isolation, constantly relying on men in her life to dig her out of trouble. In fact, the only time her gender is apparent is in these unfavourable circumstances, further evidence of this repetition of “objectionable values”.

But all is not lost for the female in Stoner comedies, since two films, Grandma’s Boy (Nicholaus Goossen, USA, 2006) and Your Highness (David Gordon Green, USA, 2011), both depict strong female characters in lead roles. Samantha (Linda Cardellini) in Grandma’s Boy is the head of development at a video games company and is just as integral to the film’s plot as the lead stoner, Alex (Allen Covert). Samantha is not only in a position of professional power, she also gets loose with the guys – drinking and smoking weed, among other things – and avoids interpretation as being simply an object for male attention.

In Your Highness, a stoner fantasy adventure, Isabel (Natalie Portman) is a warrior, constantly saving her own life – and that of hapless Lord and stoner, Thadeous (Danny McBride) – with her superior skill and determination. While she is still subject to the chauvinistic sexual advances of Thadeous, Isabel defies female subjugation, playing superior to him.

Although the Stoner comedy will likely remain primarily a male-oriented film genre for the foreseeable future, these examples hint at the possibilities for stronger female representations.

Ethnicity and Race

A distinctive quality of the stoner as a cinematic icon is that he or she is ethnically and racially diverse. Grant notes that “into the 1980s, genres and genre movies remained almost exclusively the cultural property of a white male consciousness”, adding that, in genre films, “ethnic characters are often flat stereotypes: the Italian mobster, the black drug dealer, the Arab terrorist” (Grant 2007: pp. 18, 80). While most genres have now explored ethnic variations in archetypal roles, this cannot transform the original imagery of these character types – the cowboy is still white and the mobster is still Italian.

The stoner, however, is, and has always been, non-specific in its ethnic categorisation. Man, Chong’s character in Up in Smoke, demonstrates the inherent ethnic ambiguity of the stoner. While Pedro, played by Cheech, can be read as a fairly one-dimensional, slapstick portrayal of a Chicano character, Man, on the other hand, has no definitive ethnicity. The character of Man appears to be white – he has two affluent white parents at the beginning of the film – yet Chong himself is Asian-European. When Pedro first introduces Man to the rest of his band, the bass-player asks, “Hey Pedro, where’s the white dude you said was playing the drums?” Clearly Man cannot be identified as white, or any ethnicity for that matter – he is simply a stoner. In their article, “Wasted Whiteness: The Racial Politics of the Stoner Film”, Cornelia Sears and Jessica Johnston determine that “stoners … are marked as non-white, through association with ethnic others [and] through their rejection of mainstream ideas about work and achievement” (Sears 2010). Through its filmic history, the stoner has been embodied as white, black, Hispanic, Asian, Indian, European, and even Aboriginal. There are few film genres, if any, besides the Stoner comedy that feature such a wide array of ethnic protagonists.

Grant asserts that “race, ethnicity and nationality are commonly stereotyped in genre films, sometimes together”, and ethnic minorities have “traditionally been cast in supporting roles” (Grant 2007: p. 90). The Stoner comedy is not above ethnic stereotyping, yet by reframing these characters as central, rather than marginal, the genre does much to transform interpretation of these types.

Friday, set in a predominately black, low-income south-central Los Angeles suburb, depicts a snapshot of life in this neighbourhood as told through the eyes of Craig and his friend, Smokey. Craig and Smokey are young, black and unemployed, and throughout the course of the day they sit on Craig’s porch, smoke weed, flirt with girls, interact with criminals, draw the ire of gangsters with guns, and consider taking up arms themselves. This surface representation of the black community in Friday does little to counter the association with crime, unemployment and drugs common to black stereotyping. The film manages, however, to diminish these stereotypes by elevating Craig and Smokey to roles of prominence, presenting the traditionally subordinate flat ethnic characters as rounded, three-dimensional entities. Friday successfully subverts issues of race and identity, emphasising the concerns of individuals in the film rather than those of the community, and ethnicity, as a whole. Craig and Smokey do not lament their societal or cultural station; they do not, in fact, give a thought to it. Instead, they focus on their own personal obstacles and conflicts, eventually confronting and overcoming them, and as a result are anointed heroes of the neighbourhood – and of the silver screen.

Friday is not racially charged; there is no direct comment on racial inequality, or any undertone of anger and revolt. Robert Stam, writing on race and representation in cinema, argues, “a cinema of contrivedly positive images betrays a lack of confidence in the group portrayed, which usually itself has no illusions concerning its own perfection” (Stam 2000: p. 277). Friday does not portray a positive image of black society, nor a negative one. Hoban articulates this further, stating, “Stoner movies are honestly observant and celebratory of America’s cultural diversity, not just racial diversity, without pushing identity to the fore at the expense of individuality” (Hoban 2011). By simply depicting individuals in a state of being, the Stoner comedy provides a more direct and honest engagement with genuine ethnic characters and narratives.

The Stoner comedy is apt in elevating ethnic characters above and beyond their inherent stereotypes. In Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle, Asian and Indian stereotypes are acknowledged, challenged and transformed through the lead stoner characters, Harold and Kumar. In their simple mission to get baked and devour a White Castle meal, Harold and Kumar must not only navigate through their stoned digressions, but also overcome racial stereotyping. Being stoners, Harold and Kumar know they transcend any static ethnic categorisation, yet the rest of society does not. The film delicately balances itself between confronting racism and remaining true to good old fashioned Stoner comedy fun. This is achieved once again through clever subversion of issues relating to race and identity. Harold and Kumar don’t outwardly address these issues, yet their frustrations – and the film’s negative depiction of racial ignorance – are apparent through their interactions with the film’s environment.

In the beginning, Harold, an Asian-American, is forced to take home his white frat-boy colleagues’ unfinished work for the day. They perceive Harold as a timid, hardworking and subservient employee – traits associated with a negative Asian stereotype. Harold unhappily obliges, seeming to acknowledge it is his culturally inscribed directive to do so. With the power of weed, and the will to overcome the obstacles he and Kumar face throughout the film, Harold rises above his stereotype, finally confronting his colleagues at the end. In this confrontation, Harold asserts his superior personality and intellect over his immoral white colleagues, completely overturning stereotypical assumptions. As a Stoner comedy, Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle provides an example of the genre’s affiliation with what Stam calls, “satirical or parodic films [that] may be less concerned with constructing positive images than with challenging the stereotypical expectations an audience may bring with them” (Stam 2000: p. 278).

In relation to the stoner’s rise from stock character to the hallowed halls of Hollywood folklore, Hoban writes, “The stoner is an American hero as much as the cowboy, but the cowboy was a hero of the past. What makes the stoner’s heroism more urgent and contemporary?” (Hoban 2011). In a modern world riddled with inequality, economic crises, religious zealots, the spectre of terrorism, the rapid spread of information and the decrease of privacy, the stoner is impervious. The stoner embodies a true freedom of spirit, unchained from the rigours of the ‘real’ world and the oppressive classifications of race and class.

This freedom does, however, come at a cost. While the film stoner is often exempt from critique within the confines of the film text, in the external world his or her existence is flawed. Marijuana is a drug and the stoner a drug addict. This addiction ultimately diminishes the potential for the universal celebration of the stoner, yet it is dependent on perception – whether weed is harmless or harmful, or legal or illegal. Regardless, the stoner coasts along, as an individual and as a friend, permeating and gravitating toward positive energies, always on the look-out for the next high. As the Stranger – symbolically, a cowboy figure – in The Big Lebowski comments, the stoner is “takin’ ‘er easy for all us sinners”. The torch is passed. The stoner abides.

While a thorough examination of genre at the site of the film text permits a reasonable method for identification and classification of genres and their conventions, it does have its problems and limitations. The unavoidably selective nature of genre studies brings with it an inherent subjectivity, blurring any lines of definitive genre taxonomy. In this chapter films such as Up in Smoke, The Big Lebowski and Pineapple Express have been discussed as Stoner comedies, yet arguments could be made that they are grounded in other genre categories: Up in Smoke, a road movie; The Big Lebowski, a film noir, or the auteur product of the Coen brothers; and Pineapple Express, an action comedy. This opens a debate on the systematic structure of genre as perhaps being more heterogeneous than the standard theory allows.

Selectivity is also an issue in relation to the geographical scope of this particular study, the focus of which is exclusively American. This does little to hinder the analysis of the Stoner comedy, however, as its origins and principle evolutions are all firmly rooted in Hollywood, as is much definitive genre production. Rather than condemn these limitations of systematic genre theory, their very acknowledgement encourages a further analysis and discussion of aspects neglected thus far. The conventions of the Stoner comedy as detailed here can now serve as a foundation for this additional analysis. As contemporary genre theory reinforces, the “film text itself is only one among many possible sites where genre condenses” (Watson 2007: p. 111). In order to gain a more complete understanding of the Stoner genre, it is necessary to shift the focus of enquiry outside of the text. Genre formulation can then be understood in relation to audience and industry concerns.

II: AUDIENCE AND EXPECTATION

If genre is formulated within the film text as conventions, then it is also a product of external audience expectations and industry orientations. Having analysed at length the systems of conventions Neale refers to, there is still much to be gained through an investigation of genre at the levels of audience and industry. Jane Feuer, in her article, “Genre Study and Television”, calls this a “ritual approach”, which “sees genre as an exchange between industry and audience, an exchange through which a culture speaks to itself” (Feuer 2005: p. 145). The relationship between industry and audience as it relates to genre is a more complex relationship than that of either to the film text, making it difficult to separate them into distinct levels. This chapter, however, will be particularly focused on the role the audience plays in the formation of the Stoner film genre.

Regimes of Verisimilitude

According to Andrew, “Genres construct the proper spectator for their own consumption. They build the desire and then represent the satisfaction of what they have triggered” (Andrew 1984: p. 110). Drawing upon conclusions made in the first chapter, the conventions of the Stoner comedy should not only inform subsequent productions of relevant films, but also their viewing practices – what the audience expects of the genre. In Andrew’s terms, if a spectator is anticipating a Stoner comedy, then the film will only satisfy expectations if it delivers at least some of the familiar generic conventions – marijuana, stoners and comedy – while also leaving potential for a novel twist. In this sense, genres adhere to an “economics of predictability”, producing, regulating, and distributing materials in ways that anticipate the desires of audiences and efficiently deliver those materials to them (Corrigan 2004: p. 289). Borrowing from Tzvetan Todorov’s notion of “regimes of verisimilitude”, which consist of “various systems of plausibility, motivation, justification and belief”, Neale outlines the way in which these systems function in relation to genre and audience expectations (Todorov 1981: p. 118; Neale 1990: p. 46).

To Neale, generic verisimilitude depends on a genre’s prescribed textual and aesthetic conventions. For example, Half Baked’s premise of Kenny being thrown in jail for ‘murdering’ a police horse by overfeeding it is funny in a Stoner comedy, but perhaps not so if the same scenario occurred in a drama. Generic verisimilitude is then counter-posed with broader social or cultural regimes of verisimilitude that are more in line with expectations of the ‘real’ world. Neale notes the drawing power of genres is their “regimes of verisimilitude can ignore, sidestep, or transgress these broad social and cultural regimes”, concluding that it is often those ingredients of a film that are at odds with ‘reality’ that “constitute its pleasure, and thus attract audiences to the film in the first place” (Neale 1990: pp. 47, 48).

While the Stoner comedy especially appeals to stoners, these films are often consumed by a large and varied collective of filmgoers. This broader audience, while not necessarily partaking in the act of getting ‘stoned’ in a literal sense, identify in the Stoner comedy a common mindset, ideology or fantasy that constitutes its appeal. Stoners, whose choice of lifestyle is inhibited by the law, unfavourable public opinion and negative psychological alterations associated with the consumption of pot, find in the Stoner comedy an embellished fantasy of their own existence. Participating in the regulatory social and cultural regimes of verisimilitude, fans of the genre are drawn to the Stoner comedy and its transcendent generic verisimilitude: the issue of marijuana illegality and general disrepute is sidestepped, or for the most part, ignored; the stoner is viewed as an endearing, somewhat heroic figure as opposed to a menace to society; and the narrative can carry the stoner on a journey of great adventure, thrust out of the seat to which they are otherwise glued. In viewing these films, audiences recognise, whether consciously or unconsciously, where these opposing regimes intersect and break apart, developing new understandings and expectations of the genre.

The impact of this ever-evolving genre comprehension is not limited to viewing practices. Neale argues that “The two regimes [generic and social/cultural] merge in public discourse, generic knowledge becoming a form of cultural knowledge” (Neale 1990: p. 48). For the stoner community, a thorough knowledge and appreciation of Stoner films provides an outlet and inspiration for a positive dialogue surrounding their often problematic lifestyle. The success of the Stoner comedy is fulfilled by the desires and expectations of the audience and vice-versa. Therefore Stoner comedies, and all other genre films, can be considered “not only as some filmmaker’s artistic expression, but further as the cooperation between artist and audience in celebrating their collective values and ideals” (Schatz 1981: p. 15).

An Affected Audience

An audience approach to genre demonstrates how the “specific systems of expectation and hypothesis [that] spectators bring with them to the cinema” is as imperative to the conceptualisation of genre as the films themselves (Neale 1990: p. 46). The Stoner comedy genre performs a unique role in this symbiotic relationship between audience and text as it anticipates and accounts for a psychologically altered audience.

Not only do spectators bring with them certain generic expectations, they can also arrive with a healthy dose of THC working its wonder on the brain. The psychoactive effects of marijuana can make the jokes funnier, the colours brighter, the sound more dynamic and the formal techniques more profound. The Stoner comedy knowingly accommodates this highness the audience may carry with it, making reference to, parodying or formally representing the side-effects commonly associated with marijuana. Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle parodies an anti-marijuana advertisement, playing off of the sensibility and expectations of a stoned audience. The faux commercial depicts a boy smoking his first joint, after which he exclaims, “I’m so high! Nothing can hurt me!” He then sticks a shotgun in his mouth and pulls the trigger, the sound of the gunshot thunders as the scene cuts to black and the text “MARIJUANA KILLS” appears ominously in red. Harold & Kumar are then framed on the couch laughing hysterically at the absurdity of this commercial, as does the knowing audience.

As mentioned earlier, stoners are not the only people that view Stoner comedies. For filmmakers working within the genre, the gift of an audience that may generally be in an elevated mood seemingly makes it easier to successfully engage the spectator. The Stoner comedy, however, must also appeal to the non-stoned spectator while still conveying its inherent weed-laden conventions. Relative to this discussion is Huber’s definition of the ‘contact high.’ In reviewing the Austrian Stoner/drug film, Contact High (Michael Glawogger, 2009), Huber conceptualises the eponymous notion as a metaphor for drug cinema, describing it as “the phenomenon that one person takes the drugs, and another, though technically sober, feels the effects upon contact – much like a movie viewer is supposed to plunge into the world of dopehead protagonists” (Huber 2009: p. 27).

The Stoner comedy can be seen to characterise the stoned experience not only within the text, but also in accordance with the spectator. For example, the stoner’s journey through experiences of paranoia, delusion, disorientation, euphoria and hallucination represented in the narrative and aesthetic of Smiley Face coincides with the practising stoned audience, while also appealing to the notion of the contact high, providing a deliberate representation that gives the any viewer the opportunity to engage in the world of the stoner protagonists directly through the cinematic experience.

In recognising cinema’s close contact with its audience, the development of a genre’s story formulae and standard production practices can be influenced by spectator responses to individual films (Schatz 1981: p. viii). The Stoner film, as a cinematic event, was essentially born of an audience-driven exhumation and reappropriation of Reefer Madness. Originally financed by a church group under the title, Tell Your Children, the film was intended as a morality tale based on the premise that “marijuana leads to acts of shocking violence ending in incurable insanity” (Halperin 2010: p. 196). It was not until the early 1970s, however, that Reefer Madness became a cinematic phenomenon.

In 1971, New Line Productions, in conjunction with the National Organisation for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) founder, Keith Stroup, began screening a re-cut version of the 1936 film as part of Stroup’s NORML college lecture program, delivering it to campuses all over North America. According to Stroup, Reefer Madness was “not a good movie by any standards, but the absurdity of it all touched a nerve with the students, and it made the program campy and undeniably entertaining” (Halperin 2010: p. 197).

The success of the response to this film highlighted an area of demand in the cinematic repertoire. College students, at the forefront of the late 1960s, early 1970s counter-culture and well-versed in marijuana knowledge and experimentation, now had a film that directly addressed a knowing pot-smoking audience, and its gross misrepresentation of the drug and its effects gave way to an unintended comic interpretation. The response to Reefer Madness in a sense paved the way for the impending Stoner comedy genre, cluing filmmakers in to the way a stoner audience interacts with representations of their lifestyle on the screen.

The Stoner Film as Cult

The case of Reefer Madness also leads to a legitimate discussion of the Stoner genre as a form of cult cinema, consisting of films that have a “select but eccentrically devoted audience who engage in repeated screenings, celebratory rituals, and/or ironic reading strategies” (Church 2008). Ernest Mathijs and Xavier Mendik, in their book The Cult Film Reader, articulate cult cinema through an examination of elements that contribute to a designation of this status. Of particular relevance to the Stoner film are the elements of “cultural status” – the way in which a film complies, exploits or critiques the culture it has sprung from; and “consumption” – the way the film is received, including audience reactions, fan celebrations and critical receptions (Mathijs 2007: p. 1).

The Stoner comedy as a genre is inherently affiliated with the aspect of “cultural status” Mathijs and Mendik describe. The Stoner comedy is a tangible product of the drug-experimenting counter-culture of the late 1960s and 1970s, and was – and to an extent, still is – at odds with many of the values accepted as norms in American society. Through foregrounding and celebrating marijuana and its users, the Stoner comedy is perpetually exploiting and critiquing hypocrisies evident in its parent culture through its commentary on, and representation of, law, drug use and ethnicity – as described in detail in the previous chapter. Positioned within this same society and culture, audiences that share these marginal attitudes, beliefs and practices gravitate towards the Stoner comedy and elevate it to cult status. In his writing on genre, Schatz states, “movies are not produced in creative or cultural isolation, nor are they consumed that way” (Schatz 1981: p. vii). The Stoner comedy can then be seen to function as a – primarily subversive – “politically inspired cult film”, that appeals to its audience by deconstructing the “cohesiveness of official culture…exposing its incoherencies and prejudices, and celebrating ‘lapses, breaks and gaps’ in its discourse” (Mathijs 2007: p. 10).

Second, and perhaps most pertinent to the Stoner comedy’s cult nature, is the notion of consumption. In relation to this, Mathijs and Mendik state the “key term here is ritual: as with traditional cultism, cult cinema reception relies on ritualized manners of celebration” (Mathijs 2007: p. 4). The Stoner comedy can inspire a particular practice of ritual behaviour among its audience: the smoking of pot. The cinematic event that is the Stoner comedy provides a distinct occasion for fans to congregate and celebrate stoner culture, whether by partaking in a dedicated toke-up session, or simply revelling in the counter-culture ideology that lies at its heart. This potentially illicit ritual manner of celebration, however, is not compatible with the traditional viewing practices of the movie-going public, making it difficult for the stoner audience to venture out to the cinema while still retaining their self-imposed prerogative to smoke marijuana. Tending to shy away from the public theatre, fans of the Stoner genre conduct their celebratory rituals privately and repeatedly.

Vinzenz Hediger, in “European Cinema and the Invention of Tradition in the Digital Age”, reports that the average Hollywood film “now only takes in about 25% of its revenue at the box-office, while more than 50% of the revenue comes from the Home Video market” (Hediger 2008). In the case of the Stoner comedy, these figures tend to lean heavier on the home video market. Friday, How High, Half Baked, and Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle all took in less than 10 million dollars each in their opening weekend in North America, a relatively underwhelming figure in the face of more widely appealing comedies, such as The Hangover (Todd Phillips, USA, 2009, with sequels 2011 & 2013), which opened with a 45 million dollar weekend (IMDb 2011). These Stoner comedies, however, are still in circulation and have made more than their fair share of profits in home video and DVD sales. In most instances their popularity has actually increased over time.

Marin, in commentary on the DVD release of Up in Smoke, explains that Cheech & Chong are “more popular now [in 2000] than they’ve ever been”. The stoner audience is a direct participant in what Hediger labels “new forms and patterns of movie watching”, stating, “for some years now, young moviegoers in the 14-to-28 age bracket have increasingly tended to view films on DVD at home and in groups. For many potential moviegoers, the DVD party has become a plausible alternative to a visit to the movie theatre” (Hediger 2008). John Cho described his experience of Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle’s reception during an appearance on The Kevin Pollak Chat Show.

The box office was disappointing. But about half a year afterwards, every single person I ran into had seen the movie, it seemed incongruous. It became a DVD phenomenon. I think because it’s a weed movie, it seemed like something people were happier to do at home … it was easier to get stoned. It has an underdog theme; and I think the low performance at the box office actually helped us. People passed it around, it was a secret, it was like they told each other, “No one knows about this movie you have to see it”. (Cho 2011)

Cho’s account provides a case study demonstrating the Stoner genre’s propensity towards cult cinema consumption practices. It is interesting how he notes the low box office figures actually helped drive the film’s eventual success, its underground and “secret” reputation proving the perfect ingredients for attracting a dedicated cult audience. Also, Cho confirms the stoner audience is more inclined to favour Hediger’s “DVD party” over the cinema, as it makes it “easier [for the spectator] to get stoned”.

Most Stoner comedies have undergone a similar trajectory of reception, directly paralleling Mathijs and Mendik’s definition of cult cinema, in which the “emphasis of … reception is not on box office figures and mass audiences”, but instead “relies on continuous, intense participation and persistence, [and] on the commitment of an active audience that celebrates films they see as standing out from the mainstream of ‘normal and dull’ cinema” (Mathijs 2007: p. 4).

The “Ex Post Facto” Stoner Film Genre

It has been established that genre can be understood as a fluid process. The constitution of a generic corpus is dependent not only on decisions made by the critic, but also the extent to which it is formulated by public expectations as well as by films (Neale 1990: p. 45). Here the notion of a Stoner genre becomes complex. While the Stoner comedy can be clearly identified as a distinct genre in terms of its textual, aesthetic and industrial conditions, there is also a loosely recognisable Stoner film genre – a general selection of widely varying films that are what Robert Stam calls “ex post facto designations”, constructed by audiences and critics (Stam 2000: p. 128). Under the influence of marijuana, the stoner audience employs a drug-altered reading-strategy. When a film is found to strike a particular chord with this audience – enhancing both their experience of the high they are on and of the film itself – it can then be anointed as a Stoner film. These films are ritually celebrated by the stoner audience in the same manner as the Stoner comedy, diversifying the cult appeal and selection of the genre in all its possible extensions.

The book Reefer Movie Madness is a testament to this diversity, providing an account of Stoner film favourites that are categorised under comedy, drama, sci-fi, fantasy, horror, action, sports, animated, music and documentary. Thus a film such as the Hollywood classic The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, USA, 1939) is subsumed into the Stoner film sanctum – its psychedelic aesthetic, fantastical narrative and conspiratorial link with Pink Floyd’s landmark rock record, Dark Side of the Moon (1973), all attributing to its stoner appeal (Halperin 2010: p. 254).

This approach echoes Jeffery Sconce’s notion of paracinema. In “Trashing the Academy: Taste, Excess, and an Emerging Politics of Cinematic Style”, Sconce describes paracinema as “less a distinct group of films than a particular reading protocol, a counter-aesthetic turned subcultural sensibility devoted to all manner of cultural detritus” (Sconce 1995: p. 372). For the stoner audience, paracinema’s focus on a reading protocol helps to define its practice of consuming films while stoned, enabling a “counter-aesthetic turned subcultural sensibility”. Sconce asserts, however, that paracinematic culture has an “explicit manifesto … to valorize all forms of cinematic ‘trash’, whether such films have been either explicitly rejected or simply ignored by legitimate film culture” (Sconce 1995: p. 372).

This is where the Stoner film departs from the terms of paracinema. While the stoner audience more often than not will support an esoteric strain of cinema, it is not so exclusive. In fact, in the hands of its audience, the umbrella of Stoner film can be held over not just any film, but almost every film. Jay Chandrasekhar, a self-professed stoner and director of the Stoner comedy Super Troopers (USA, 2001; sequel 2018), gives a first-hand account of his experience as a spectator, stating: “Every single movie we saw, we’d go high; it was such a major part of our life” (Halperin 2010: p. 6). The stoner audience anoints its films less on the grounds of the mercilessly selective paracinematic culture, gravitating more toward the realm of cinema “buffs” who revel in their “appreciation of, and trivial knowledge of, literally every single film, loving it simply because it is part of the medium, and loving film facts simply because they are film related facts” (Mathijs 2007: p. 6).

Under the topic of “Best Movie to Watch High?” on online stoner forum Grasscity, a quick trawl through user responses lists films such as Star Wars (George Lucas, USA, 1977), Finding Nemo (Andrew Stanton, USA, 2003), Akira (Katsuhiro Otomo, Japan, 1988) and The Usual Suspects (Bryan Singer, USA, 1995), along with the regular Stoner comedy standards. This is evidence of a varied and non-discriminatory community of film appreciation (Grasscity 2011). Halperin & Bloom testify to this, claiming that “for more than 40 years, films have been an integral part of pot culture, helping shape individual interests and fashions, and igniting imagination, chatter, and passion … These [stoner] films are as much a part of the stoner psyche as Bob Marley” (Halperin 2010: p. 6).

An analysis of genre at the level of audience reveals a more complex system of genre construction than originally determined at the textual and aesthetic level. While initial understandings and conventions of genre are formed at the site of the film text, they soon become ingrained in the movie-going consciousness, developing a set of evolving expectations that a spectator applies to each subsequent viewing of a film. The blurring of generic and cultural knowledge enables genres to “usurp the function of an interpretive community”, rendering them not as neutral categories, “but rather ideological constructs that provide and enforce a pre-reading” (Feuer 2005: p. 144). The Stoner comedy is, then, as much the product of its audience’s desires and expectations as it is the intent of the filmmaker or studio; its counter-culture aesthetic and values reflects those of the stoner mentality.

The success of the Stoner genre relies not on box-office takings or critical acclaim, but rather on its status as a cult form of cinema. This status is attributed to the genre by a “select but eccentrically devoted audience who engage in repeated screenings, celebratory rituals, and/or ironic reading strategies” (Church 2008). The key area of cult celebration among the stoner audience is that of its rituals – of these, the most obvious is its penchant for getting high. While a film is not required to initiate a session of smoking the reefer, the Stoner comedy provides a distinct occasion for the audience to conduct its ritual. The unlawful practice of this audience makes attending the public theatre difficult, so a shift to methods of private consumption – DVD and home video – affords the Stoner genre a consistent, ongoing appeal. Stoned viewing practices also contribute to the expansion of the genre, from the Stoner comedy to a more loosely defined category of Stoner film. Inclusion under the Stoner film banner is entirely subjective to the experience being enhanced by the effects of marijuana, rendering almost any film a possible addition to the corpus.

The conventions deduced from a textual and aesthetic approach to genre study help to identify the Stoner comedy and its influence within other forms of cinema. An audience approach, however, problematises this account of the genre as it serves to formulate a broader concept of the Stoner film – one that creates exponentially subjective opinions regarding a generic corpus. The Stoner comedy is then not only a film genre with its own set of conventions, but perhaps the industrial response to the appeal of the Stoner film – the cinematic occasion for the stoner audience to congregate and celebrate the films they love. This leads to the third and final level of genre study: industry.

III: INDUSTRY AND THE ECONOMY OF GENRE

Having analysed genre and its operation in relation to the Stoner comedy in terms of textual and aesthetic conventions, and then audience expectations, this chapter will discuss the way in which the industry constructs notions of genre. Paul Watson, in “Genre Theory and Hollywood Cinema”, suggests: “At a general level, work on genre seeks to understand film as a specific form of commodity and, at a more refined level, attempts to disentangle different instances of that commodity” (Watson 2007: p. 112). In viewing genre as a commodity, it can be understood as a product – the manufacture and spread of which is determined by its prior success and current demand.

Historically, the avowal of film genres originated from the Hollywood studio system. The term genre is commonly used in a broad sense which sees all films as participating in a genre; however, the concept springs from “a more restricted sense of the Hollywood ‘genre film,’ i.e. the less prestigious and lower budget productions or B-films” (Stam 2000: p. 127). It is through this system of production that an “economics of predictability” became apparent as a feasible and successful approach to filmmaking. Adapting an industrial system of mass production, film genres enabled Hollywood movie producers to “reuse script formulas, actors, sets, and costumes to create, again and again, many different modified versions of a popular movie”. While audiences, returning to these familiar genres, were found to know what to expect and how to respond (Corrigan 2004: p. 289). Although the classic studio system has long since dissolved, genres still remain an appealing mode of production for filmmakers and producers alike. Accounting for this, Watson categorises the ways industry utilises genre, serving it to function as:

“(1) a financial security blanket for the industry by providing a logic, or framework, for organising its output so as to capitalise on previous models of success and thus minimise financial risk; (2) a set of precepts and expectations for audiences to organise their viewing; and (3) a critical framework for reviewers to arbitrate between the distinctiveness and putative success of the product and the taste of its implied audience”. (Watson 2007: p. 110)