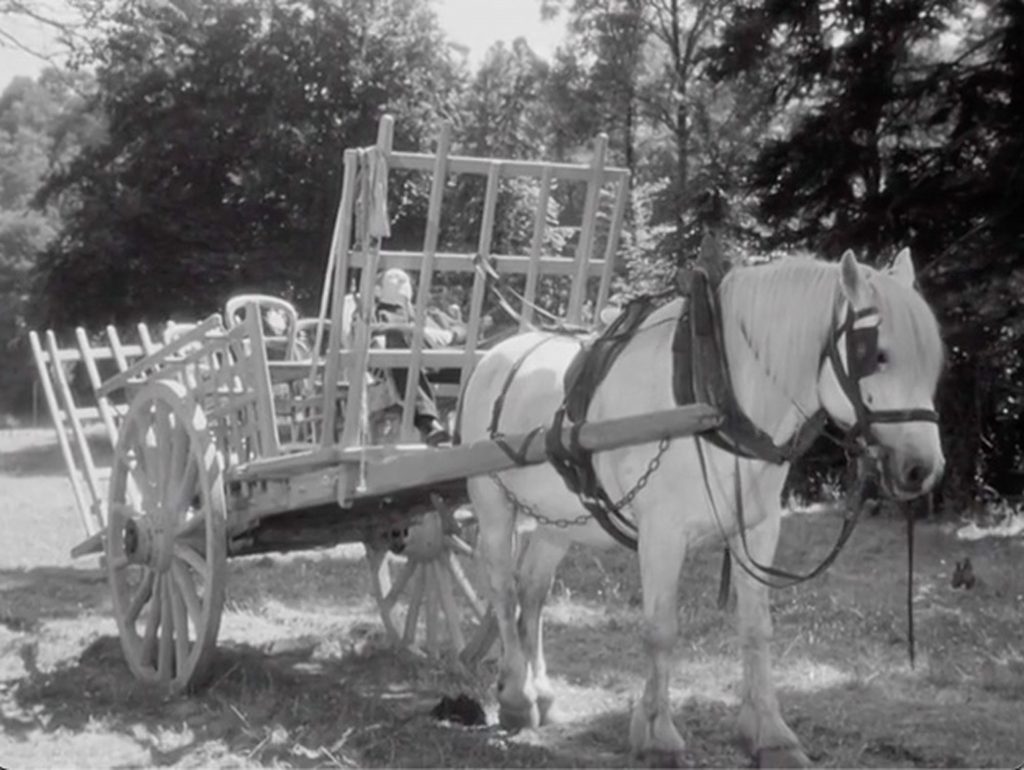

Two remarkable moments in Max Ophüls’ Le plaisir (1952), both “La maison Tellier,” second of the film’s three movements. We have already been introduced to the eccentric, charming, late nineteenth-century European world through Ophüls’ and Jacques Natanson’s adaptation of Guy de Maupassant narrated subtly, mellifluously, and cautiously by Jean Servais off-camera and visualized in the gliding imagery of Christian Matras. A certain house in town has been legend to the men of the community, thanks to the gay repartee to be heard therein late into the nights and the warm hospitality (not without champagne) of the proprietor Julia Tellier (Madeleine Renaud) and the half dozen or so gaudily dressed young women who assist her. In the country church of Julia’s brother, there is to be a Holy Communion of the young niece, and so off she goes with her girls alongside, first somewhat adventurously by train and then, from the tiny station and into the landscape, by horse cart.

To taste the delight of the first moment upon which I choose to remark, it is not necessary to know the details of the church adventure, its preamble, or its conclusion since the station, our setting for now, is at some remove from the brother’s house, and the sacred perfume of spiritual matrimony has not flavored the air that far off. We are told in Servais’ most gentle voice, even as the train slows to its halt, of how the brother, Joseph Rivet (Jean Gabin) is coming to meet the guests in a cart drawn by a “little white horse,” and indeed, moving parallel to the train but on the near side of a line of trees, through the twittering leaves of which the mid-day sunlight is beaming, the cart is entering from screen left, pulled, just exactly as we finished hearing with our very last breath, by a little white horse. Sunlight dappling the horse as he prances slowly and halts. Sunlight showing him off as he stands waiting with the sweetest patience. This sweetness overflowing the scene, too, so that Joseph is infused with it instantly, the loving husband of the faraway sister of very polite Julia Tellier with her girls kept in line. A sense of calm pervading the atmosphere, since the horse is perfectly at rest and the sunlight is perfectly charming, and now the train, indicator of modernity, is drawing off and leaving us in peace. Joseph moves with purpose and intelligence, but not with speed. He crossed the little bridge, found his party, and is now guiding them back to where they can climb aboard the wagon. The horse is happy, patient, unconcerned with the sorts of picayune details that might plague the sort of urban social life that, for this tiny holiday, Julia & Co. have left behind.

We are treated now to several longish chained shots in which we see the horse bringing the women forward to Joseph’s place, along a curling path through lovely trees, beside a field of wildflowers, and so on. Only one melody is stated in this little sequence, and then restated again and again like the theme of a sonata’s slow movement: the friendly simplicity, dreamy tranquility, and utterly true civilization of, and implicit in, this bucolic setting and in Joseph who is hosting us there. Let us return to his little white horse.

What is it – what can it be – about this short phrase coming from Servais, “un petit cheval blanc,” that so intoxicates even as we first see him pull into the station area. What is it – what can it be – that prepares us always already to adore this creature, to rest with him, to be his companion, to find joy in moving forward through life at the pace he is choosing. One would not feel the need to claim that before staging his pas de deux in Central Park for The Band Wagon (1953) Vincente Minnelli had seen and found joy in this film of Ophüls’, in order to recognize the special charm in our curious bonding with the horse (as we do in the Minnelli), our willingness to let him have us, as it were.

To hear that Joseph would be driving a “white horse,” un cheval blanc, fails entirely to bring the romantic leaning we adopt with the creature as he is. A white horse is nothing but a horse of a certain color (to quote from The Wizard of Oz [1939]), this horse not that horse; the white horse brings horsepower, a horse’s devotion to this kind of enslavement. But a little white horse is something – someone – else again, because now the whiteness picks up the air of grace. Now the horse is touched with a special gift, and now, too, we will have to sympathize with his littleness as he bears forward a cart with all these women and Joseph, too. He’s pure, this little white horse, and innocent, a requirement of the deeper narrative since, to be brief, Julia Tellier and her associates are anything but innocent and Joseph is, perhaps, as we may surmise, in between innocence and experience. We apprehend, too, that Joseph is not oozing in funds (his sister from the city surely is) and so to pull his farm cart he can afford only a little horse, a little white horse (both so cute and so vulnerable) and between them the horse and he can get only a certain amount of profitable work done in a sunny day.

It is that I wish to point to this little white horse, merely. To learn of the journey it leads, and where this journey can take us, we will no doubt be happy to forget the little white horse as a character, notwithstanding that the narration explicitly makes identification. Ophüls is a little white horse, too, of course, bringing us in a cart that holds many people to a journey forward. One might add, bringing us happily, even serenely, and steadily, without friction or bumps, without hitting any walls . . . because like the little white horse he knows the way.

It is one of the lovely qualities of the little white horse that he knows where he is going and doesn’t really need to be driven by Joseph at all. It was fifteen years after this film came out that Kenneth Boulding pointed me to Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s The Phenomenon of Man and its idea of the nošsphere: the sum total of knowledge of all the human beings on earth, ever, added to which is the sum total of all the artifacts of human knowledge, such as the milk horse who draws his chariot every morning from house to house on the same route while the driver dozes. Our little white horse is a perfect exemplar of the artifact of human knowledge, except that we can see him stretching further than that. He is natural, quite as natural as could be in his genteel littleness and his pristine whiteness, his sparkle, his touching energy; and in his naturalness he is of course perfectly at home here in the forest glades of the country. Through this little white horse, analogue for Ophüls, the nošsphere merges with, includes, nature itself.

A second marvelous, and surprising little moment is more choreographic, pungent instead of soothing. One of the guests, Madame Rosa (Danielle Darrieux), more impetuous and somewhat more world-weary than her companions, has been flirting with Joseph and for a small practical reason he enters her room at the house. The wife goes searching for him, finds him there, and, scolding loudly, drags him out and sends him on his way. All this a passing fillip of narration, not a tale in itself. To reach this bedroom Joseph, and Rosa before him, must have ascended to a balcony made of wood, walked the length of it, and descended a step or two to the door. Now in haste and humiliation he must journey in reverse, and Ophüls has his camera posed upon the balcony where he will have to pass. We start looking at him coming out of Rosa’s door, and as he steps our way we turn with a graceful pan and then follow him out of the shot. Again, simply a choreography involving performer and camera, and not even a complicated one. But our Joseph has his dignity, after all. He is just a little piqued at being criticized in this way, since he has been very proper as well as very amenable to all the guests. He is, in truth, an innocent (another innocent!), and he would like his innocence to be known somehow, against the rather vociferous background of his wife’s rant. But there is no one to hear him protest, nor, since no one is directly near, anyone to hear him at all. He would like at least to show his innocence, if only there were eyes.

But suddenly there are eyes. There is an eye.

Because just as he moves his body past the lens, which is catching him midriff upward, he turns his head slightly toward us and raises his eyebrows in exasperation, this a gesture made explicitly to the audience, that is, to the camera that is otherwise in this film not present (present through non-presence) as stand-in for us, the camera eye for our eyes. You know me, Joseph seems to say. You know me already, and you know that I would never take advantage, and my wife is just jealous, and if nobody in this whole house understands – understands what is happening but also understands me – then at least, wink wink, I can let you know that I already trust that you do. And because you know me, I speak this way to you. We have a secure feeling about Joseph, and he can continue onward through the day letting the wife’s jibe slide away.

What is astonishing about this aside to camera, is the filmmaker’s adeptness in guiding it, since we are watching in Le plaisir a triad of little films all shown in objective third-person, and through the Servais voice. All these are stories from nowhere and everywhere, about creatures who do not recognize that they are in stories, that they are being told about. And for a split second a character does know he is a character, yet not only a figuration and creation but also a spirit, call it a character-spirit, one with a heart and therefore with feeling. Ophüls manages to let us notice all this but with no emphasis of any kind, not even an extra frame or two in which the actor can prolong his turn, and this creates a magical sense of doubling in which, at the same instant, we are being addressed as an audience suddenly made visible to the character before us and as an audience invisible to him and all other characters in these (and all) stories. Dramaturgically the aside is vital, too. Joseph cannot proceed without gaining definition as henpecked and innocent, else we will believe he has dallied with Rosa and this will introduce to the story a line of development it could not sustain in its brevity, a line also extraneous to our thinking about him and about the quiet countryside – since he would be acting more like one of Julia’s facile customers back home. On the other hand, since Rosa has been little beside flirtatious, he can hardly retain his masculine dignity without at least peeking in her room. He is skating down a two-edged blade, too, just as Ophüls is.

Joseph – it is worth pointing this out – not only shares his feeling of the instant with viewers, he shares it in a gesture of a certain tonality: he knows us, he trusts us, he likes us, he is comfortable with us, we are his friends. Very abrupt this moment: a moment of the admission of friendship between a character, who for the viewer’s everyday reality does not exist, and the viewer, who normally does not exist for the character. To point a step further: a gesture of friendship from the character, not the actor. The actor, Gabin, will “go along” with Joseph here and do everything he is required to do in order to embody what the character wants. For Gabin himself to offer a gesture of friendship would be nothing but false; perhaps even coldly false.

None of this escapes Ophüls.

As to these two moments I have pointed out, one would be lying about the filmmaker and his film were one to make the claim that they have a centrality. One could stretch an argument and say they are both about a kind of innocence, and a kind of illumination. But the film in its three movements is no less complex than Beethoven, and what I am pointing out with the white horse and the quick eyebrows – Vous savez bien-sér que c’est comme a! – is that such elaborate richness can be blown into the air by this filmmaker, in much less than a breeze, while he goes about his business giving us a world that never quite was.

Stanley Cavell averred in The World Viewed that his way of studying films was by remembering them, and that to this method, this “lack of scholarship,” some advantages flowed. I know that I do likewise, and that in considering by remembering I am making Le plaisir my own, which is what I believe it was as I watched it; and the filmmaker, as he worked the articulation of it, my own, too.