And lightning blinded all, however strong

—Hesiod, Theogony, trans. Dorothea Wender

When evil comes, it comes at an angle: this is the sense evoked by Charlotte Dacre in Zofloya (1806). In its most climactic passages the scenery shifts from a Venetian noble’s castle to the mountain range behind it. Victoria de Loredani, having committed two murders, is now in the process of committing a third. The episode begins when her unwilling lover awakes from the effects of a potion she gave him. He sees Victoria in his bed, “blasting his strained eyes with her hated image,” and with terrifying swiftness throws himself upon a sword. [1] The woman swears revenge on his waifish fiancée, currently held captive in the bowels of a mountain. The distance is great, the path steep and arduous, yet Victoria crosses it like a thing possessed. First, “she ascended the sloping rock” to the place of confinement, then “rushed hastily down” the declivity to its entrance; and then, grabbing her captive, she drags the girl back “up the irregular ascent.” [2] Up, down, and once again up, in the space of a few paragraphs over two pages. And the sinner grows more sinful with every inversion. “Now, look down,” Victoria tells her victim. “See’st thou?” They glance over the precipice at the torrent below. “Oh, mercy! mercy!” cries the other, who shakes herself loose and takes refuge near a tree. [3] But the aspect of the tree is enough to suggest her fate. For the girl, “perceiving that hope of escape was vain, caught frantic, for safety, at the scathed branches of a blasted oak, that, bowed by repeated storms hung almost perpendicularly over the yawning depth beneath.” [4] The oddly precise geometry says something important. Dacre’s tree is most certainly blighted and damned in the sense the eighteenth century gave the word blasted. [5] But the tree and all around it, the very sense of space itself, are also blasted in the modern sense of blown-up or exploded. If made into a picture, it would strain the eyes to look at.

Evil comes at an angle: this is also the sense intended in the early scenes of Desperate (1947). A “rip-snorting gangster meller” by Anthony Mann, it was the first film over which he had any real control. [6] And so it is the first in which we see that blasted space which marks all his best work well into the 1950s. The film is ostensibly the story of Steve Randall (Steve Brodie), ex-soldier with a pregnant wife and a small-time trucking business; and who, in trying to make an honest dollar, finds himself entangled in a world of crime and violence. It is, more truly, a story of two spaces, one prim and full of light and another quite blasted. The first, Steve’s apartment, is introduced to viewers with a close-up of cake mix. The camera pulls back to show two youngish women, Steve’s wife to the left and her friend to the right. They lean toward each other over the mixing bowl between them. Since their legs hug the frame lines and their heads nearly touch, they form the contours of a pyramid whose base is the kitchen table. Even when one sits down and the reverse-shot series follows, nothing dispels the wholesome feeling of stability. It is this, a world of normal lighting and eye-level placements, to which the husband returns with his flowers and jokes.

But then he must return a phone call: a lucrative job awaits him. A graphic match on the phone to another just like it brings us directly into a den of vice. The man who answers looks repulsive in the camera’s low angle and in the shadows thrown across him from the key light placed below. And after he offers Steve fifty dollars for the job, he hangs up and moves to his fellows offscreen. The camera reveals a room and the shadowy men within it, of whom the most important is Walt in the middle distance. The camera holds a long shot before cutting abruptly at 90 degrees to the right of this angle. The jolt of our displacement is amplified further by the outrageous composition of the new viewpoint. The camera spies Walt (Raymond Burr) through the back of a chair whose spindles break him neatly into five pieces. The boldness of the graphic pattern is not a symbol or cipher. It merely shows the character’s function as an agent of blasting, a function he will execute when the fall guy comes before him.

Steve botches the job intentionally and, in return, gets roughed up at the hideaway by a gang of heavies. Walt enters and approaches and the image cuts sharply from the back of Steve’s head to the crushing blow that Walt gives it. The cut is quite precisely at 90 degrees, from a back view to a profile of this human punchbag. The movement of a shoulder, barely hinted in the first shot, becomes a fist that strikes the camera as much as it does the victim. It comes so near the lens that it falls out of focus and never quite regains its contours as it draws back. Henchmen take over where their leader left off. In doing so they jostle a low-hanging fixture, which now swings its beam in every direction. The big man looks on sedately and with a hint of pleasure as his face is lit up and then plunged into darkness; lit up again, and darkened once more.

*

Blasted space occurs when the spirit of malevolence expresses itself in the spirit of geometry. It makes use of the techniques that cinema offers to stress the angularity of a series of surprising views. It may emphasise shadows but less for their possible symbolism than for contrast and contour, for the lines that they draw. The same is true of low and high angles, which are valuable for the impact they gain through foreshortening. Even deep focus is made a blasting agent, being used not for realism but to yank the eye diagonally. Camera movement is perhaps slightly demoted and, when used, is used to stress the composition. The eye makes a series of crossings and doglegs as it follows the lines laid down on the screen before it. It does so in order to feel a disquiet that symbols can only reference by the detour of thought. The archetypal image of this form of construction is the lightning-blasted tree with its branches bowed severely. Space is renewed under the burning force of evil that comes at an angle, and leaves more angles behind it.

Anthony Mann was one of cinema’s consummate blasters, and almost all agree he had an “eye-catching” style. [7] And yet what one critic wrote of Mann forty years ago can be adapted here with only minor alterations. Mann “has been [treated] by critics and scholars attuned [mostly] to intellectual, political, or sociological achievements.” [8] He is treated in terms of genre, notably crime films and westerns, of which he made twelve and ten samples respectively. [9] Sometimes his work is seen as expressive of contradictions of statehood or gender; these are symptomatic readings. [10] One even finds a few traditionalist accounts of an auteur concerned with “perennial human issues.” [11] But there is something to be said for the early claim of Jacques Rivette that Mann’s importance as an artist was formal in nature – and that the violence one finds there is a means of achieving form. For “those punches, weapons, dynamite explosions have no other purpose than to blast away [faire sauter] the accumulated debris of habit.” [12] In this Rivette kept faith with the director himself, who stressed the pictorial aspect in every interview he gave. The ideal film for Mann was one that could omit the spoken completely and still be understood. [13] Although he never achieved this aim, he valued a simple story: one whose speech he could reduce as much as was possible and whose conflicts he could physicalise or play out through violence. [14] Only then was it possible to “make something of it pictorially.” [15] All of Miller’s songs in The Glenn Miller Story (1953) had to be “pictorialised,” had to be more than songs; and however much Mann hated the dreadful Strategic Air Command (1955), it at least gave him views of the sky beyond the sound barrier. [16] Elsewhere he speaks of “a visual conception of things,” of “great pictorial qualities,” of “tremendously pictorial” settings and locations. [17] Whatever moral or intellectual interests he had were always subjected to the demands of his camera. “He saw things,” said a colleague. “He understood the camera.” [18] And the camera was an agent of a staggering graphic power that found its main outlet in the poetry of violence.

Some have expressed surprise that Mann, who came from theatre, should have had such a confident sense of the frame’s dynamics. But when he staged his first plays for the interwar theatre, the stage itself was still conceived along the lines of painting. It was not a box in which some actors merely declaimed but a carefully regulated pictorial space. Rouben Mamoulian, for whom Mann worked as an assistant, felt one should be able “to take a snapshot of the stage picture at any moment.” [19] The Federal Theatre project, where Mann worked in the 1930s, was full of the kind of teaching later formalised in textbooks: division of the stage into areas of emphasis, the use of the human figures to form new lines and shapes. Perhaps most important was the theoretic distinction between pictorial composition and “picturisation.” The latter was used “to inject meaning into the stage picture” once the tone had been established by graphic qualities only. [20] The kinds of line, for example, had each their own feelings. The horizontal was a restful, the vertical a surging line. Straight lines were stern and formal, curved ones free and intimate. And if the diagonal was relatively uncommon, that was due to its “arresting” or even “bizarre” quality. [21] One felt a note of conflict from a crossing diagonal. All this Mann took to heart when he began making films. His visual conflicts would issue in violence that prompted a change of setup and new lines of tension.

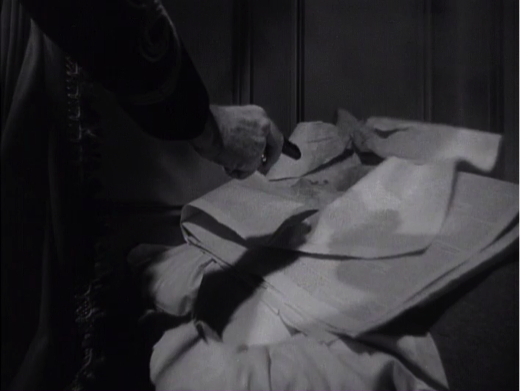

Whether story and subject dictated style, or rather was dictated by the pursuit of “daring shots,” is a question we should be careful not to answer too quickly. [22] Certain is that the creation of an angled, blasted space could occur for Mann only with men of violent character. As an artist “whose women are his least convincing creations,” his films are almost always homosocial in nature. [23] We might even say with Susan White that male-to-male affection can be expressed only as violence in these films. [24] But violence is more than just sublimated eros. Its positive quality is the blasted space around it. For in classical films there are two standard ways to activate space in a dramatic scene with figures. One is to have a character look in some direction; the other is to move the character in that direction. And therefore athleticism or even a certain violence – the bounding or hurtling of figures through space – is the basis for blasting-open and renewal of space. What Manny Farber described as “Mann’s inhumanity to man” is what allowed that director to cover ground effectively; allowed him to avoid the aesthetic dead-end of “incessantly, perpetually reiterating the same space.” [25] Almost any Mann protagonist, on either side of the law, must eventually expend his energies in a shocking burst of violence. Since the American film industry for most of Mann’s lifetime forbid the female star from engaging in violence, it became a necessity to get her out of the picture: “to send her away somewhere,” as Mann himself put it, “so she won’t be in your way, and you won’t need to film her.” [26] Thus most of his women are romantic props and tokens. Their spatial possibilities are comparatively limited, and so they get from this director a perfunctory treatment. The only real exception is the character Vance (Barbara Stanwyck) who, in The Furies (1950), wears pants and gives orders – and blinds her new stepmother with a pair of scissors. The insert of the scissors as they fall to the ground is long enough to let us see the streaks of blood on the carpet. Dark banisters in the foreground slice the frame diagonally as the assailant descends the stairs, both blasting and blasted. Perhaps progress in movies could be measured by the frequency with which women can motivate this form of construction.

“Violence is always pictorially shocking,” Mann said. “You can achieve fantastic effects of violence just by implication and design. And it is one of the good parts of our medium – it tends to shock and tends to excite the imagination and to rouse feelings in the audience that they’ve seen something and experienced something.” [27] Only in 1947 would Mann start to find material that consistently answered his needs as a stylist. After Desperate he moved from RKO’s B-unit to a Poverty Row studio, the Producers Releasing Corporation, which itself was in transition to becoming Eagle-Lion. Before it dissolved in 1951, it specialised in thrillers and police procedurals. Its product, moreover, was made fast with small budgets, and so gave ample room for play in “the experimental ‘B’s.’” [28] In two years Mann completed four films as director: Railroaded! (1947), T-Men, Raw Deal (1948), and Reign of Terror (1949). The first was completed in ten days or less, the last had the luxury of twenty or twenty-five. [29] All of them allowed for the refinement of blasted space: sharp angles, chiseled shadows, shock cutting, and the diagonal.

But the clearest, because most concentrated, example of blasting is a sequence Mann directed in someone else’s film. Rumors began to circulate in the late 1960s that He Walked By Night (1948) was full of Mann material. Recent inquiries all but confirm that suspicion. It would seem that Alfred Werker, the credited director, fell sick or was indisposed after shooting had commenced. For a colleague on the payroll to step in without credit was not unusual at Eagle-Lion, or anywhere else. Scholarship credits Mann with four crucial scenes, or twenty-two minutes of the completed film. [30] Of these the most applauded has been the finale, a chase with bobbing flashlights through the sewers of Los Angeles. But there is another more instructive from the viewpoint we have chosen, one that is set in a lab for electronics. Even more useful is its contrast with Werker’s treatment of the laboratory setting slightly earlier in the film. What follows is offered as additional evidence that Mann in fact did direct this splendid sequence.

We will probably never learn how well he knew the project before he directed his twenty-two minutes. But surely he knew the outlines of the true-crime scenario and the aberrant psychology he was called upon to picturise. It was based on a case still fresh in the public’s mind when He Walked By Night was put into production. Only two years before, a certain Erwin M. Walker began the string of crimes that led to his capture. He was “a menace to society,” “beyond rehabilitation,” in the words of the judge who sentenced him in 1947. [31] The sentence was death for the murder of an officer while casing a meat market in northern Los Angeles. When taken into custody at the end of 1946, he was sleeping with a machine gun beside him on the bed. Yet another was mounted in one of his stolen cars; hence his future nickname of Erwin “Machine Gun” Walker. He was an ex-army man, former police dispatcher, and trained engineer with a specialty in radar – ultimately too intelligent to convince the courts of his insanity. War had made him strange, asocial and morose; his exploits included safecracking and the theft of electronics. This last point involved him for the first time with police, who staked out the home and business of an electronics dealer. As Walker strolled up the driveway, a cop sprang from behind the house, while another ran across his path in a flanking maneuver. At this point “the suspect whirled, firing an automatic,” felling both officers and then escaping around the back. [32] Such power to act suddenly, to whirl about and shoot – to strike with the crash and terror of lightning – made him an excellent candidate for the dynamic use of film space.

Walker in the film is renamed Roy Morgan (Richard Basehart), who makes two separate visits to the site of the ambush. In the first scene he is merely a strange, intense man who brings his stolen wares for consignment at the laboratory. After an establishing close-up of the lab’s exterior placard, it dissolves into a view of the building’s interior. The long shot of the lobby is quite rigid in its balance. Its arrangement is symmetrical around an archway in the background, toward which the eye is led by three receding chandeliers. The front door, left of frame, faces another door, right of frame. There are shadows against the walls but none that approach to blackness, and the lighting gives a sense of pleasant gradation. The only item to break the symmetry is a table set askew – for no other reason than to add a sense of depth. The time is late morning or early afternoon: the time of business hours, of public transactions. The image in all regards upholds this public quality. It hides nothing, we feel, as Roy enters from the street, crosses to the receptionist, and exits frame right. The camera pans with him, first right and then left. Thus a symmetry is nested within another symmetry.

This pattern is typical of Werker’s direction, as is the use of actors like columns to support the frame lines. In the course of twelve shots we will have seen the establishing placard; the lobby framed symmetrically; two symmetrical pans; and a dialogue whose framing starts on a room’s corner and ends with a reverse-angle of another, identical corner. The whole scene is built on these predictable figures that stabilise the image and lead the eye gently. Precisely this blandness is what Mann will blast open in a scene of equal length but much greater intensity. The most obvious sign of difference is a dramatic fall in shot time from a median of thirteen to only four seconds. And with an increase of characters, in the distance among them, and in the amount of movement they are called on to perform, the resulting construction makes greater demands of synthesis. Space becomes action as its lines thrust and parry; it gives the eye a chase by its feints and deflections. Each view is designed to reinforce the feeling that when evil comes, it comes at an angle. One can say of Mann what has been said of Murnau: “In this startling succession of angles the horror becomes complete.” [33] Mann, incidentally, was one of Murnau’s admirers. [34]

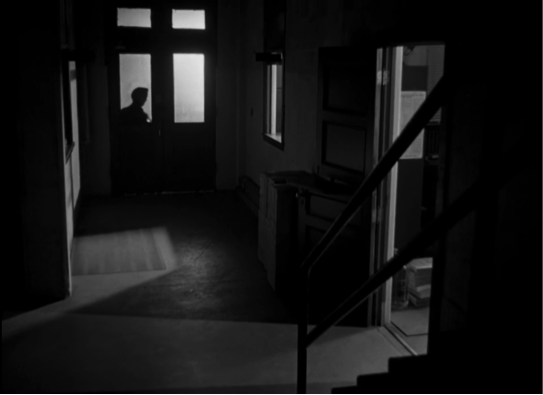

In Mann’s scene the lab has been turned into a stakeout. The time is night, not day, when the figure of Roy emerges rather casually from the street. The camera pans left as he enters the foreground and then it pans right as moves to the nearby alley. The image does not dissolve but simply cuts to the next, thrusting us into the interior of the building. It is as if Mann had watched Werker’s rushes the day before and decided to make his mark by a studied inversion: by changing the pan’s direction from right-left to left-right, and the dissolve into a cut, even lighting the placard so as to turn its letters black. And when we see the lobby we see it from what was once the vanishing point of our earlier view of it.

The camera is recessed behind the darkened archway, where officers Jones and Brennan are seated in the foreground. The lines of the architecture lead not to the center but rather to a point a good deal left of center – to the tiny figure of Mr. Reeves (Whit Bissell), working in his office, seen through another archway across the chasm of the lobby. The spot of light on his face from the lamp on his desk pulls the eye through both arches along a diagonal. This architectural arrangement makes no sense at all but is graphically necessary to the plan of what follows. From here the film cuts to a medium shot of Reeves, then to a close-up of a clock on his desk. We have been inside the building for less than ten seconds and have already traversed the extremes of scale and distance. We are brought, thereby, to a pitch of excitement that the rest of the sequence will only ramp up. The clock face as it nears 6:56 PM cuts back to the shot of Reeves alone in his office.

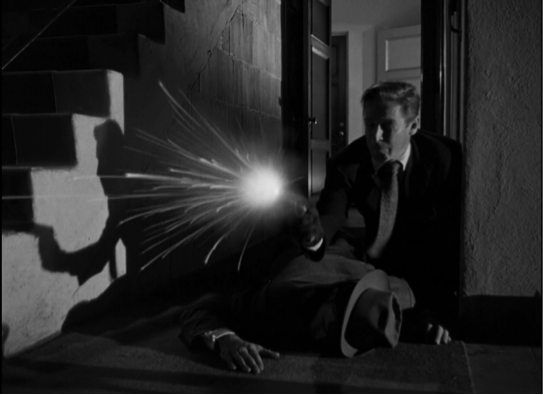

The purpose of a stakeout is, of course, to lure one’s enemy to a place one has mastered and made predictable. All points of entry are to be accounted for and guarded. It is curious that the detectives should somehow forget this, sitting side by side instead of parting ways for coverage. And so they leave unattended the building’s backdoor, which Roy enters silently from the dark alley. A long shot of the hallway shows him approaching as a solid silhouette in the frame of the backdoor window. The deep black of his figure against a stark light from behind is a contrast carried through the shot as a whole. As lit by John Alton, the design is quite graphic, with an irregular polygon of shadow traced out across the floor. From the shadow’s beginning at the bottom of a rightward doorway, we follow its contour left across the frame. It turns, sharply, to form a narrow peak. From there it moves diagonally into frame center before it travels up and left, each line like a razor’s edge. The high-angle view makes the railing in the foreground descend yet more severely, cutting the doorway twice. As the intruder proceeds – peering through an aperture and finally through the door at Reeves – he stops, leaps, stops, and leaps in a halting, staccato rhythm that echoes the graphic pattern. At this point the sequence cuts to another view, from over Roy’s shoulder to Reeves in the background. Between them is a hallway mostly in shadow, its planes distended by the short lens along a diagonal. The angle changes almost as soon as it is grasped, for the succeeding close-up of Roy is a 180-degree reversal. Our gaze must whirl around, and because Roy is moving his direction is reversed across the shots as well. “Reeves!” he whispers harshly, his face half in shadow. The shadow is hard and dense, a pane that bisects him. His hearer jumps up in the answering reverse-shot. All these views of Reeves, taken from Roy’s perspective, are exactly perpendicular to the sightline of the officers. Thus in the next five shots as Reeves looks to them, and they look to him, and he looks at Roy and Roy looks at him, we feel the tension not merely of dramatic oppositions but of sightlines intersecting at right angles to each other.

We have considered fifteen shots, or a total of ninety seconds. Over two minutes and thirty-two shots remain. Discussion of each would be long and unrewarding, and so the reader should now imagine a crosscutting pattern. The officers split their efforts in something like the flanking movement described in the original news story. Jones exits through the front door and, offscreen, makes his way around the building and through the alley to the back. At the same time Brennan moves from the lobby to an area that should logically be the machine shop, but is now only a hallway. While Roy looks at Reeves in a straight line from the doorway, Brennan moves in a direction parallel to this axis.

Roy knows he is ambushed – knew it before arriving – and his knowledge is confirmed by the shadow of Jones, which flits across the window of the rear doorway. [35] Roy looks, starts, turns and turns again, in a low-angle shot that shows much of the ceiling. All the lines of the image now lead the eye to a second-story landing at the top of a stairwell: the lines of the walls, the slant of the doorway, the ceiling beams, the railing, and eventually Roy’s eyeline. A cut on his movement as he bounds up the stairs brings us to an even lower and more foreshortened view. In reality, the railing turns level when it reaches the upper landing. Visually it appears as two diagonal lines that connect to form an apex at the composition’s center. And each line is extended by other lines within the picture – by the line of the ceiling, by the head jamb of a doorway. Together they form an X that Roy comes to occupy, his face catching light from the adjoining room. So blasted and blasting is he that the diagonals seem to emanate from his standing figure. He enters the doorway at the top of the stairs, where the landing descends immediately into another stair with railing. At its bottom is Brennan, who advances with caution. Roy sees him, crouches, and readies his gun just as his opponent moves offscreen right. Low and high angles alternate so that the thrust of the respective railings keeps changing position across the change of shots.

Brennan moves toward the camera and begins to round the corner.

Roy rises from his place at the top of the stairs.

Brennan peers around the corner, body held taut, edging into light from the open door at left.

His movement continues in a low angle shot from the door’s other side, with another breach of continuity.

Roy moves as well, he crosses the upper doorway; his hand grasps the railing and he vaults into the air.

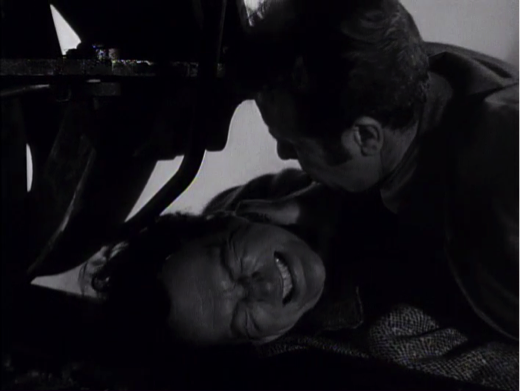

In a long shot he lands on the unsuspecting Brennan, who crumples to the floor and gets brained with a pistol.

This finally resolves the tension of the narrowing gap between them; it also resolves the tension of their ambiguous placement, for they still seemed miles apart in the shot before this one. The tension is further eased by the entrance of Jones, who trades bullets with Roy in six shot-reverse-shots. The scene fades to black as Roy staggers through the alley, wounded by a bullet he will later extract himself. Thus in less than four minutes Mann saps and destroys the academic symmetries previously wrought. We, for our part, come to know structure not just by surveying but actively exploring: enduring strain and tension as much as the characters while our eyes traverse the ruins of a space blasted open. A play of looks conducts the camera to people far removed. The task of the director is to bring them together in a way that will activate as much of space as possible. Even the perimeter of the building is suggested by the journey offscreen of the officer Jones around it. Taken together, these forty-odd shots give a total picture of the setting, the lab; they are like panels of a paper template that, when folded, produce a house or some other tectonic structure. But spread out in time, they hang crookedly at the hinges, bringing us up short at every join and juncture. A space we thought we knew from our prior contact with it reveals itself fully under pressure of violence. All areas, levels, angles and the lines resulting are open to the camera as it frames the human figures. Shadows carve the floors, low and high angles clash, directions are reversed, sightlines intersect. Diagonals and perpendiculars carry the day – stressing oppositions, putting viewers through their paces. One seeks a point of rest but is kept at high pitch by deferrals and deflections of the fascinated eye. The conventional editing pattern that closes the scene has the force of ejaculation after buildup of friction.

*

A.C. Bradley’s comment on the villain of Othello applies just as well to He who Walked By Night: “The most delightful thing to such a man would be something that gave an extreme satisfaction to his sense of power and superiority; and if it involved, secondly, the triumphant exertion of his abilities, and, thirdly, the excitement of danger, his delight would be consummated.” [36] Power, exertion, skillful execution – feelings of the active will – are the basis of this character’s appeal to any audience. Yet his utter lack of motive, his inscrutable psyche, also alienates our sympathy and taints our enjoyment. It makes him very nearly an abstract force of evil that must be extinguished before the credits roll. Let us see now what happens when the blasting agent is good, in the sense that his violence hurts the right people.

Sergeant Kennedy (Dick Powell) has motives one cannot possibly impugn in Mann’s film The Tall Target from 1951. He wants to save a man, a president-elect, from being murdered by conspirators the following day. And since the statesman in question is Abraham Lincoln on the eve of inauguration in 1861, anyone responsible for saving Lincoln’s life would share also in the glory of that memorable term of office. He could do practically anything without alienating the sympathies of the film’s target audience, the American people. He can break the law, contravene his superiors, force men into confession under threat of pain or death, and blast the space around him while yet remaining good. Patriotism is his least and his most important quality: least because it pales beside his more apparent virtues of wit, cleverness, strength, obsessive drive, most because it gives these a valid field for their enjoyment. There was, historically, a Superintendent Kennedy of the New York Metropolitan Police in the 1860s. He had little to do with the alleged plot against Lincoln that history refers to as the Baltimore Plot. It was actually Allan Pinkerton who uncovered or, as some allege, invented the conspiracy that made Lincoln decide to pass through Baltimore in secrecy. A president-elect with his favorite detective on a trip through rebel territory might have made a good comedy. The first treatment of the story was actually a Southern love triangle set aboard the train and with Lincoln in the background. But it sat unproduced at MGM for three years before it became the story of a renegade cop. [37]

Our fictitious Sergeant Kennedy gets on the train to Baltimore at the depot in Jersey City on a cold winter day. His reports of a conspiracy have been met with derision; no one believes him, least of all his superior. Punishment awaits him if he presses his claims. And now he operates entirely in an extralegal sense, having turned in his badge in a fit of hysteria. Even his boarding of the train is illegal since he cannot find the friend who bought and holds his ticket. Both man of law and outlaw, he is the classic American hero – strong and self-reliant – a good man with a conscience, who uses force when force is needed. In this he differs from other passengers like the spinster abolitionist, who makes a great to-do about her “literary jottings.” He has more in common with the conspirators themselves, some of whom are on the train and who have little use for “jottings.” His appeal is much heightened by the actor Dick Powell who retains his old boyishness in this late hardboiled persona.

Both Powell and Mann were late additions to the project, long after the screenplay was written and approved. Some give this as evidence of Mann’s disengagement from a routine assignment he simply phoned in. True, the film is less flamboyant than the ones that precede it. Its politics and especially its treatment of slavery are, at best, somewhat confused. Mann himself thought it derivative and a failure; it lost money when released and is utterly forgotten. [38] But what impresses today is its sheer entertainment and the taste for mild sadism Mann gives to its hero. Impressive, too, is its treatment of space, which unfolds under the pressure of a slowly creeping evil – as if a bolt of lightning could tarry in violence as it lays waste the land and inflames the beholder’s eye. If Mann added nothing to the film in pre-production, he yet blasts its peace of mind as well as its space.

The first villain encountered is the man in Kennedy’s seat who has stolen the cop’s identity, ticket, and gun. Kennedy resumes his search for the friend who should be there. He finds a pair of glasses and their owner soon after, cold and lifeless on the floor outside the baggage car. Kennedy has an idea. He must find a gun. But a gun finds him first, its barrel pressed into his back. His impostor leads him off the train at the first opportunity. At this point the image “goes all diagonal,” as it so often does in Mann’s mature films. [39] The train stretches across the screen from bottom right to upper left; in the next shot it runs from left to right instead. The change is a match cut on the movement of the actors but it is in all regards a “bad” sort of match. It reverses the positions of the actors in space, and it yanks the eye on one diagonal before yanking it across the other. Its harshness is heightened by a change in tonal value from mostly black to mostly white as steam fills up the image – fills it suddenly and by ellipsis in what is really a jump cut. Kennedy has only a moment to maneuver. But the heavy is of only intermediate difficulty and loses his gun at the first punch from Kennedy. A high angle shot of the gun on the tracks is bracketed by low ones of the men against the train. Thus train and track form two opposed diagonals whose opposition is stressed with each cut between them. Like the first sparks on the ground before the consuming fire, it is prelude to a scene of spectacular violence. Wim Wenders has said that Mann will only end a scene “when everything that could have taken place [there] has come to pass.” [40] Since the action of this film is almost wholly on a train, it seems inevitable that we should also at some point go beneath it. The struggle for the gun gives Mann his opportunity as the men fall on each other, panting and desperate.

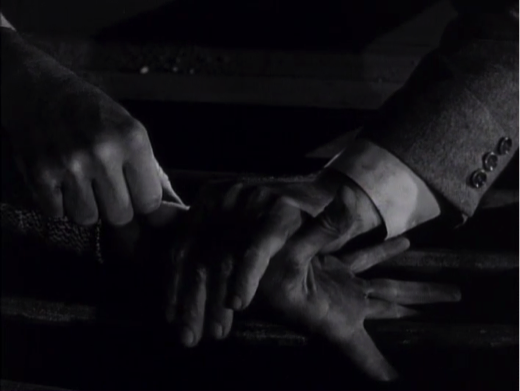

The camera frames them tightly in medium and close shots whose placement on the ground is itself a kind of judgment. The closer one gets to the surface of the earth, the more primal and savage men’s violence becomes. What happens below the train is of a piece with other scenes like the death of Agent Bearnes beneath a harrow in Border Incident (1949), or Will in The Man From Laramie (1955) dragged through dirt and fire. One loses the dignity that comes with upright posture, and the only principle of conduct is raw, naked force. The hand resumes its function as primitive weapon, balling up into a mallet or squeezing like a vise. The vocal apparatus, if not reduced to grunting, speaks in imprecations and blunt interrogatives.

Kennedy disarms the gunman by slamming his hand repeatedly until it flies open like a five-pointed star. He then proceeds to use the tracks as an impromptu tool of torture, pressing the other’s neck against the cold iron rail. Steam turns the background into a stark white canvas, and the men into figures of a primeval drama. It is something from a nightmare, a scene from the unconscious. Beside them to the left is the outline of a wheel. This too is a darkened mass against the glaring backdrop. In a cutaway shot, the crew readies for departure. We return to the wheel in close-up as it creaks into motion. From there the camera pans to the face of the heavy whose neck will be crushed if he remains where he is. “Who’s giving you orders?” screams Kennedy amid the clangor. “Who is it?” But the only answer he receives is some hysterical spluttering in which the word “savage” is audibly leveled at him. And now their struggle is seen not beside but through the wheel, through its spokes and outer rods, cutting the men to pieces and deleting the questioner’s face. Fear gives the pinioned man an unexpected second wind. He overmasters Kennedy, rolling atop him, and this turn of events is echoed by another change of angle. The wheel presses closer to the tender skin of men; it encroaches with the power of absolute mechanism. The struggle is decided when Colonel Jeffers (Adolphe Menjou), another passenger, shoots the assassin dead with a wild shot in the dark.

He and Kennedy retire to the colonel’s room, which slowly but surely bears the mark of blasted space. We have seen the room before. The men had had a drink, they discussed their political differences, and the film cut between them in standard reverse-shots. Their return to the compartment now is likewise prosaic: a single take of two minutes in medium-long shot, broken only by a close-up insert of an item shown to Jeffers. These images assure us that we see what we need to see, and that the colonel whose room it is has nothing to hide – that he is, like the camera, entirely on the level and, like the glass he drinks from, entirely transparent. Still we have our suspicions, and we have them confirmed a little later in the movie.

All is as before when we return to this room again. The camera is placed on the train compartment’s bed, facing the bar and washstand and the door to the hallway. Curtains with fringes drape the frame’s upper corners. The room rolls and rocks from the movement of the car. Kennedy and Jeffers enter and Jeffers sits down to smoke while the other lies down on the berth to rest awhile. But a third presence undermines the routine exchange of pleasantries. It is Jeffers’ reflection in the mirror on the door. The mirror, of course, was there in the earlier scenes. Characters stood before it, smoothed their hair in its refection. It was just a piece of décor with a pragmatic function. Now it becomes conspicuous and even annoying. Since Kennedy has drawn a newspaper over his face, which reposes in the foreground right, we are likely to look beyond him to Jeffers in the background left. But whenever we look at Jeffers our eyes are deflected all the way across to the room and over to the mirror. The right-angled pull is almost irresistible despite the smallness of the stimulus to be seen in its reflection: hardly more than the colonel’s hands as they hold a cigar, light it with a match, shake the match until extinguished, smoke the cigar. The distraction becomes unnerving, as if one is being asked to look away from something: to see and not see. This visual tension issues in violence when Jeffers pulls a gun and shoots Kennedy in the face.

Luckily the victim “pried the lead out of the cartridge” and the only damage done is to a bit of shredded newsprint. What follows is full of incident, local colour, conspiracy, sideburns, turnabouts, and attempts at social commentary. Eventually Sergeant Kennedy returns to the private room, unconscious and dragged there by another heavy. The train pulls into Baltimore, where Lincoln should be speaking. A close-up of Jeffers as seen through his compartment window is replaced by a long shot perpendicular to the close-up. Filming from the bed, the camera placement is familiar and yet quite unfamiliar due to changes in the mise-en-scène. The curtains of the bed are drawn so that Jeffers is seen between them in the narrow band of space that their edges permit. At the bottom of the screen there lies a rumpled mass, which the tilting camera shows to be the hero bound and gagged. The lines of force within a room of 200 square feet are still being redrawn on this, our fifth visit. Its blasting has been steady, subtle, and prolonged – equal to the cunning of the villain whose room it is – ever since an irksome mirror first drew our eyes rightward. That the mirror is in fact a portent of evil is later shown when it reflects a message traced out in the frost.

THE MAN IS ON THE TRAIN, Jeffers scrawls on the window as he runs along the platform when the train departs the station. The man of course is Lincoln, who boarded in secrecy, and the message’s recipient a Confederate assassin. Resolution is rapid and vengeance is swift as Kennedy gives chase to the soldier through the aisles. Perhaps it occurred to Mann that no scene of importance had yet been staged upon a gangway between two moving cars. But we cannot leave the train until all ground is covered, until everything that could have taken place there has come to pass. As the men burst outside and wrestle for the soldier’s pistol, the camera frames them frontally against a rush of scenery. The noise of the whistle punctuates the smack-bang of fists. Shots of the struggle alternate with perpendicular views of those who watch in fear from the rear door of the car; and since each shot is only three or four seconds, their right-angled sightlines collide with the force of blows. Kennedy falls; the camera catches him from behind. He staggers his assailant, also seen from behind; which means we shift abruptly 180 degrees in space to ensure we get a double view of figures tumbling at us. The conflict is decided when Kennedy holds his enemy over the gangway and the ground that rushes past them. There is a close-up of wheels. The man loses his grip and falls, and he appears to be dead as he tumbles in the dirt. His killer slumps over to pause and take breath, utterly exhausted by the violence that consumes him. This is what lingers and festers in memory when, two minutes later, we see the Capitol building.

*

The Tall Target’s detective is a variant on the character Mann was elsewhere developing in his series of westerns. It is a type well described by Jacques Rancière as “incapable of embodying either justice or vengeance.” [41] He “belongs to no place, has no social function and no typical Western role.” Usually he nurses an intensely private grievance that the ad hoc legal system allows him to make good on. “He acts and that’s it, he does some things,” writes Rancière, and yet his success is “the success of the film.” [42] As for his enemies, “they will all fall.” [43]

Jim Kitses calls him the overreacher type, and to this type we might assign a special graphic figure. [44] It is the image of an arrow aimed and released, then retrieved and shot again, as many times as needed. An arrow soars through the air but not under its own impulsion. It encounters friction and resistance, and it may miss the target. The painter Paul Klee understood its psychology – the human dreams conjured by the image of an arrow. “The broader the magnitude of his reach, the more painful man’s tragic limitation,” he writes. “How does the arrow overcome friction? Never quite to get where motion is interminate. Revelation: that nothing that has a start can have infinity. Consolation: a bit farther than customary! – than possible?” For the arrow is always the answer to a question of how far and how high one can go at this moment. “Over this river? This lake? That mountain?” asks Klee. [45] In The Naked Spur (1953) it is a cliff that Howie Kemp must climb.

He climbs it in order to apprehend an outlaw perched at its top, a man from his past (Robert Ryan). He will capture this outlaw and bring him back to Kansas and “sell him for money,” as Howie later says through tears. He has tracked him all the way to the Rockies of Colorado, an immense distance by any measure on horseback and foot. No reason or motivation is given until later for Howie’s current business or his general derangement. Few can forget his rage and hysteria when he hauls out the criminal’s waterlogged body. “The money,” he raves, “that’s all I care about that’s all I’ve ever cared about… alright that’s what I’m doing that’s what I’m doing.” The money is for the homestead that his girlfriend sold from under him. It is 1868; he had been away at war.

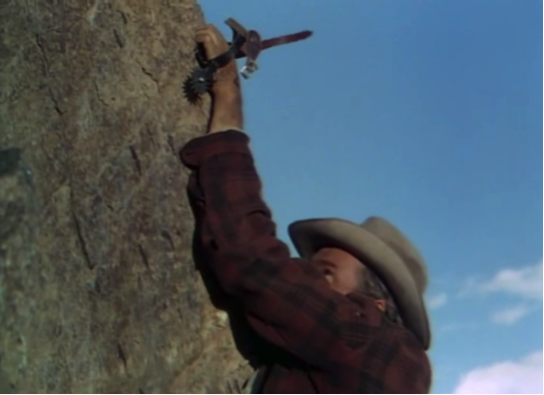

His entrance into the film is visually no different from what one expects of the entry of villains; and this is reaffirmed by a pattern of resemblance that binds him to the outlaw, to a shared history in Kansas. [46] From a bucolic long shot of an open field through trees, the camera quickly pans to a boot in its stirrup – the heel ending in a spur like a small metallic sunburst. He hitches his horse, draws his revolver, and creeps from the camera through a tangle of brush. He comes unannounced upon an old man (Millard Mitchell). The intrusion is as much a surprise to the viewer because the camera contravenes the cues of the shots preceding. Only now do we see his face, the actor James Stewart, who played the neurotic type in so many Mann westerns. “Sure came up quiet” says the old man, a trader, to the tight-lipped one who frisks him and empties his rifle. Howie shows him a wanted poster and makes no correction when the trader mistakes him for an officer of the peace. They set off in pursuit of the outlaw whose trail Howie lost some way back, now hiding among the cliffs. There, up ahead, blasted space awaits them with a force that justifies the saying “the image hits the screen.” [47]

False sheriff and deputy move uphill on horseback, and the camera frames them from increasingly low-angle placements. They are, soon, drastically foreshortened against the rugged cliffs that tower above them. Such planar disparity combined with a play of heights is a potential of the western landscape, one Mann would often use. He uses it here to make an image that assaults us with an avalanche of rocks that tumble at the camera. The rocks grow in size from mere specks in the background to russet-coloured chunks that thunder past our heads. They disorder the image with an all-over quality and make clouds of dust behind them that obscure the setting’s contours. The men rear their horses and dash out of frame but the camera keeps its fixed, low-angle position – thus blasting the viewer with the rocks meant for Howie. Doubtful as to whether the rockslide was natural, Howie grabs his rifle and peers up at the sky. The camera shows the plateau more or less from his perspective, its outline cutting cleanly across the azure. Two crags seem to dovetail at an obtuse angle, forming a hollow in which anything might appear. Back on the ground with Howie, the camera slowly tilts to follow his gaze up along the rock face. The shot is gratuitous at the narrative level but it stresses the landscape’s vertiginous aspect – indeed stresses it by showing not just the foreshortened product but the very process of foreshortening as the camera keeps tilting. A black hat, tiny, pokes out above the contour of the jutting cliff. Howie fires, aiming high, but the hat recedes like a specter amid the pinging ricochet. What he gets for his trouble is another violent rockslide that crashes upon him and also on us. The rocks fall yet a third time a few minutes later; each time they seem to hit the screen harder.

And with no villain visible beyond the outline of a hat, the blasting appears to stem from Howie alone. It is he who brought the trader and the audience here. It is he who now attracts the notice of an ex-lieutenant (Ralph Meeker), and he who leads both men to their violent deaths. The several close-ups of Howie as he scans the craggy surface, close-ups that let us see the wildness in his eyes, turn reverse-shots of the cliff into emanations of his turmoil. By climbing this rock in order to claim his bounty, he plunges headlong into the heart of blasted space – and drags us there with him, kicking dust in our eyes. He reaches over the cliffside of his own obsession, and ultimately overreaches when he loses his footing. As an arrow meeting friction, he misses the target, and the rope burns his hands on his way back to the bottom.

Over the course of the film he will suffer worse indignities. Of these the most notable is getting shot at by an Indian, which wounds him in the leg for the rest of his journey. This occurs in the course of a brutal, frenzied slaughter of a dozen Blackfeet braves who pursue the ex-lieutenant. His crime is a great one: he raped the chieftain’s daughter. For this and other reasons, Howie boots him from the party. But the man is loath to forfeit his portion of the bounty and so he embroils everyone else in his troubles. Hiding on the road in ambush, he readies his rifle as Howie hails the chief. Their figures in the distance are already broken by the lines of spindly trees that clutter the foreground. Evil comes at an angle, in this case as a bullet 45 degrees to Howie. The chief slumps over dead and the carnage begins. The natural landscape soon loses its coherence. Points of view multiply across forty-two shots whose average length is only one to three seconds. The continuity of the trail is shivered to pieces by the first bullet fired, and by the many that follow. All twelve braves will die, and their dramatic falls from horseback every five to ten seconds is a rhythm with its own appalling beat of devastation. Some hurtle down the hill right up against the lens so that linear perspective is lost in the dust and blurring. Blasted space is further marked at two crucial points by crossings of the axis that reverse Howie’s position. The eye of the viewer must move in all directions, the mind work much harder to synthesize the views, so that the final long shot of the forest clearing comes as an immense relief and lasts half a minute. But the relief is tinged with irony. For the field is strewn with bodies, a whole heap of dead.

The Naked Spur makes no attempt to probe the Indian question, notwithstanding Howie’s sadness at the loss of life entailed. That would involve a more basic reflection on his own role as a white man in the general dispossession. What the film does resolve is one figure’s ability to scale a cliff and to go a bit farther than customary. Opportunity again emerges when the outlaw escapes, kills the good-natured trader, and takes refuge on another high plateau along the trail. This gives the film its neat but only partial symmetry, for the style is rather different in this cliff-climbing scene. Despite the extreme high angles on Howie’s approach, there is little at the end that could be called blasting. When he starts to ascend the rock by skirting its edges, the camera frames him in straightforward medium or long shots. Twelve shots depict his progress up an incline, around a bend, and finally up the wall where his demon awaits him. With no visible distortions, there is no pathetic fallacy, and the cliff becomes merely an object for Howie. Strength of will and body are all he needs now to surmount it. He makes this ascent without even a lasso, with only the naked spur we saw in the film’s first image. Removing it from his heel, he uses its roweled edges to hook into the rock that would otherwise repel him. The outlaw hears its chink-chink from his perch up above and crawls over to investigate, rifle in hand. Framings of the two men alternate until they meet in one image where plateau turns to wall. No image could be more forthright, more plain and reassuring. Someone sets out to do something and with effort, he does it. The camera aims to capture this doing and does it. And the reason to end a film this way is because, says Mann, “the audience has the impression that they could have done it too.” [48] They know that they have seen something and experienced something. They have gone somewhat farther than customary, than possible, when Howie throws the spur right into his enemy’s face.

*

Desperate, He Walked By Night, The Tall Target, and The Naked Spur each exhibit what Nöel Burch calls a structure of aggression: “an almost musical interaction between moments of tension and moments of respite, in the form of more or less pronounced crossings of the pain threshold.” [49] The crossings can be based on content or form or both, so long as they produce a steady rhythm of discomfort. Mann’s images involve us in a structure of aggression, in physical and optic punishment that we suffer with the characters. “Suffer” must be read as both endure and permit; we glory in the trials to which our vision is put. Burch argued that discomfort or even acute pain could reinforce the structure of aesthetic experience. In this he was successful. But he did not push the thought as far he might to attempt an explanation of why this is so – why a detour of displeasure, first roused and then resolved, should make the final harmony all the more exquisite. If we can answer this question we can also understand the appeal of blasted space, which is far removed from beauty.

What taxes eye and mind can never be beautiful. Varieties of this dictum appeared in industry literature throughout the 1940s, Mann’s formative period. “One of the most enjoyable aspects of a good motion picture,” they said, “is the careful camera angles chosen to secure successive scenes that are restful to the eye.” [50] And: “The eye should travel up one end [of an image] and move easily down, without break or jerk.” [51] And: “We must not strain the eye with too much picture.” [52] Such advice was aimed equally at amateur and professional. It repeated the advice of the preceding generation and indeed of academicism since at least the eighteenth century. Beauty is that which leads the eye gently from point to point within a picture along an endless circuit; and ugly is that which distracts and confuses and makes the eye smart from its overexertion. Clearly Mann does not belong to this academic tradition.

Instead he courts everything broken, irregular, hurried, and changeful. The feelings he inspires are neither melting nor restful. They are, rather, tensile and strained. They are precisely those feelings we associate with the sublime since Edmund Burke described it in 1757. The sublime, with its “croud of great and confused images; which affect because they are crouded and confused,” is evidently more than just privation of beauty. [53] It offers an experience wholly unique to it, an experience we might call the pleasure of overreaching. It pleases by displeasing, by roughening perception, pushing the senses further than they typically go – so far indeed that they go beyond sense. Towering mountains, the star-stippled sky, a raging storm at sea all give us great difficulty. Each is hard to grasp as a whole in our perception. Precisely this is what gives them their aspect of sublimity, or rather gives us sublime feeling in the course of our perceiving. This feeling and perceiving is essentially time-bound; its structure is sequential, like the structure of narrative. First the thing evokes some fear for oneself. Then fear is replaced by a feeling of pleasure. The pleasure arises from hints of infinity that, per Immanuel Kant, belong only to human reason. For we cannot depict the infinite, we can only suggest it, and whatever suggests infinity is just a spur to that idea. Reason alone could dream of something so far past the sensible as infinite time and space and infinite number. And in being thus reminded of reason’s “vocation,” its “power” and “superiority,” one can look upon even the most blasted of spaces and smile at their inadequacy to the infinite idea within us. [54] One can aim or stretch farther than one can actually go; can overreach and meet resistance, yet still hit a greater target.

Film theory’s discourse of “classical” cinema – the group style to which Mann would perforce belong – has perhaps put too much emphasis on the supposed appeal of unity. Smoothness, “ease and plenitude” are simply nonexistent where blasted space holds sway. [55] For with Mann as with so many action directors, the films are most appealing when they give our eyes hell. We enjoy the disturbance and we even rush to meet it when it comes at an angle or confounds us with rocks. We move through blasted space to scale our own cliffside and thus achieve a triumph of our perception. “Labour,” Burke writes, “is not only requisite to preserve the coarser organs.” Our eyes and ears need exercise, “they must be shaken and worked.” [56] What follows the shake-up is known as delight. Pain is roused and resolved, and roused and resolved, until the senses return to their fullest acuity. They snap to attention and become more observant. They may even attain new skills, which cause yet more delight. And the critique of ideology or violence in movies will have to contend with these more basic gratifications. [57]

The final shot of The Naked Spur is revealing in this regard. As Howie rides off with the dead outlaw’s girlfriend (Janet Leigh), Mann frames him in a long shot within a sprawling field. Having tested himself against forces of evil – forces at an angle, forces he invites – sanity is given back to him in mind and image both. Even his leg appears to have healed. Yet this return to himself has come at great cost, a cost Mann inscribes into the final mise-en-scène. The field is strewn with trees in every direction. They look as if blasted and blasted by lightning. A swell of music does nothing to reduce their piteous quality. In their prostration they resemble a whole heap of dead; and they recall our own efforts as the viewers of blasted space.

Notes

[1] Charlotte Dacre, Zofloya, or The Moor (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 221.

[2] Dacre, pp. 222-223.

[3] Dacre, p. 224.

[4] Dacre, p. 225.

[5] Dr. Johnson gives the following for the verb form of blast: “To strike with some sudden plague or calamity,” “To make to wither,” “To injure; to invalidate; to make infamous,” “To cut off; to hinder from coming to maturity,” “To confound; to strike with terrour.” Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, 6th ed. (London, 1785), s.v. “blast.”

[6] Wear., “Desperate,” Variety, May 14, 1947.

[7] Paul Willemen, “Anthony Mann: Looking at the Male,” Framework, no. 15-17 (1981): 16. Other descriptors include “baroque” and even “very visual”: Robert E. Smith, “Mann in the Dark: The Films Noir of Anthony Mann,” in Film Noir Reader, ed. Alain Silver and James Ursini (New York: Limelight, 1996), 197; Ernest Callenbach, review of Anthony Mann by Jeanine Basinger, Film Quarterly 33, no. 4 (1980): 49.

[8] Jeanine Basinger, Anthony Mann, expanded ed. (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2007), p. 9.

[9] Jim Kitses, Horizons West (London: Thames and Hudson, 1969), 29-80; Stephen Handzo, “Going Through the Devil’s Doorway: The Early Westerns of Anthony Mann,” Bright Lights 1, no. 4 (1976): pp. 4-15; Robin Wood, “Man(n) of the West(ern),” CineAction, no. 46 (1998), pp. 26–33; Max Alvarez, The Crime Films of Anthony Mann (Jackson, MI: University Press of Mississippi, 2014).

[10] For example Michael Renov, “Raw Deal: The Woman in the Text,” Wide Angle 6, no. 2 (1984): pp. 18-22; Douglas Pye, “The Collapse of Fantasy: Masculinity in the Westerns of Anthony Mann,” in The Book of Westerns, ed. Ian Cameron and Douglas Pye (New York: Continuum, 1996), pp. 167-173; Susan White, “T(he)-Men’s Room: Masculinity and Space in Anthony Mann’s T-Men,” in Masculinity: Bodies, Movies, Culture, ed. Peter Lehman (New York: Routledge, 2001), pp. 95-114; Jonathan Auerbach, “Noir Citizenship: Anthony Mann’s Border Incident,” Cinema Journal 47, no. 4 (2008): pp. 102-120.

[11] William Darby, Anthony Mann: The Film Career (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009), p. 266.

[12] Jacques Rivette, “Notes on a Revolution,” trans. Liz Heron, in Cahiers du Cinéma. The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave, ed. Jim Hillier (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), 95. The original text is “Notes sur une revolution,” Cahiers du Cinéma, no. 54 (1955): pp. 17-21.

[13] Anthony Mann, quoted in Charles Bitsch and Claude Chabrol, “Interview With Anthony Mann,” trans. Alison Dundy, booklet for The Furies (Criterion Collection, 2008, DVD), 18. The unabridged original appears as “Entretien avec Anthony Mann,” Cahiers du Cinéma, no. 69 (1957): pp. 2-15.

[14] Mann, quoted in J. H. Fenwick and Jonathan Green-Armytage, “Now You See It: Landscape and Anthony Mann,” Monthly Film Bulletin 34, no. 4 (1965): p. 187.

[15] Mann, quoted in Christopher Wicking and Barrie Pattison, “Interviews with Anthony Mann,” Screen 10, no. 4 (1969): p. 47.

[16] Anthony Mann, quoted in Philip K. Scheuer, “Tony Favors Camera Over Film Dialogue,” Los Angeles Times, June 25, 1950; Bitsch and Chabrol (French original), p. 12.

[17] Anthony Mann, quoted in Bitsch and Chabrol (Dundee trans.), 24; Mann, quoted in J.H. Fenwick and Jonathan Green-Armytage, “Now You See It: Landscape and Anthony Mann,” Monthly Film Bulletin 34, no. 4 (1965): pp. 186, 187.

[18] Philip Yordan, quoted in Pat McGilligan, “Philip Yordan: The Chameleon,” Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), p. 357.

[19] Rouben Mamoulian, quoted in David Robinson, “Painting the Leaves Black,” Sight and Sound 30, no. 3 (1961): p. 124. Mann mentions his work with Mamoulian and others in a 1967 television interview, The Movies: “Action Speaks Louder than Words,” included on the Criterion DVD of The Furies.

[20] Alexander Dean and Lawrence Carra, Fundamentals of Play Directing, rev. ed. (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1965), 173. Dean’s first edition appeared in 1941. Mann, as Anton Bundsmann, worked in the New York arm of the Federal Theatre where Dean’s work was taught in the classes on direction. Anthony Buttitta, “Teaching Teachers: Complete Technique of Production,” Federal Theatre 2, no. 1 (1936): 19-21. Compare Mann in Scheuer: “By picturising [the actor] in a certain way at a certain moment we can make him say more than he could in a whole act of spoken dialogue.”

[21] Dean and Carra, p. 168.

[22] Anthony Mann, quoted by Jean-Claude Missiaen in Alvarez, p. 147.

[23] Handzo, p. 10.

[24] White, p. 109.

[25] Manny Farber, “Underground Films” (1957), Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies, expanded ed. (New York: Da Capo, 1998), p. 13; Farber, quoted in Editors of Cahiers du Cinèma, “Manny Farber: Cinema’s Painter-Critic” (1982), trans. Noel King, Framework, no. 40 (1999), p. 45.

[26] Mann in Bitsch and Chabrol (Dundee trans.), p. 22.

[27] Mann in Wicking and Pattison, p. 36.

[28] Phil Tannura, “The Experimental ‘B’s,’” American Cinematographer 22, no. 9 (1941): 420, 443. Strictly speaking, Mann’s last true “B” was Railroaded!. Cimberli Kearns, “Making Crime Matter: The Violent Style of the ‘Formative B’ Film,” The Spectator 17, no. 1, (1996): pp. 89-100.

[29] Mann’s estimates in Wicking and Pattison, pp. 35-36.

[30] See Alvarez, pp. 139-151. Interestingly, Variety reports that Mann “was brought over to the Metro lot after his standout job on ‘He Walked By Night’ for Eagle Lion [sic].” Herm., “Border Incident,” Variety, August 31, 1949.

[31] Harold B. Landreth, quoted in “Officer Slayer Must Die for Crime, Says Judge,” Los Angeles Times, June 12, 1947.

[32] “Two Policemen Shot in Gun Battle; Assailant Vaults Fence and Escapes,” Los Angeles Times, April 26, 1946. See also Alvarez, pp. 135-139.

[33] Martin Schlappner, “Evil in the Cinema,” in Evil, ed. The Curatorium of the C. G. Jung Institute, trans. Ralph Manheim and Hildegard Nagel (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1967), p. 133.

[34] Mann in The Movies: “Action Speaks Louder than Words.”

[35] The similarity of this detail to Robert Ryan’s first appearance in The Naked Spur, described below, might be offered as further proof of Mann’s authorship here.

[36] A.C. Bradley, Shakespearean Tragedy (1904; New York: Penguin, 1991), pp. 212-213.

[37] Alvarez, pp. 214-223.

[38] “I tried to do a Hitchcock… but I’m only partially satisfied with the result.” Anthony Mann, quoted in Jean-Claude Missiaen, “Conversation with Anthony Mann (Cahiers du Cinema)” (1967), trans. Martyn Auty, Framework, no. 15-17 (1981): p. 18.

[39] Adrian Martin, audio commentary for The Man From Laramie (Eureka!, DVD/Blu-ray, 2016).

[40] Wim Wenders, “Mann of the West: Anthony Mann,” The Pixels of Paul Cézanne: And Reflections on Other Artists, trans. Jen Calleja (London: Faber and Faber, 2018), p. 55.

[41] Jacques Rancière, “Some Things to Do: The Poetics of Anthony Mann,” Film Fables, trans. Emiliano Battista (Oxford: Berg, 2006), p. 74.

[42] Rancière, pp. 78, 87.

[43] Rancière, p. 77.

[44] “Anthony Mann: The Overreacher” is the chapter title in Kitses, Horizons West.

[45] Paul Klee, Pedagogical Sketchbook, trans. Sibyl Moholy-Nagy (1925; Basel: Lars Müller, 2019), p. 44.

[46] See Basinger, pp. 79-106.

[47] “I heard this expression yesterday, ‘to hit the screen,’ that’s fantastic, in English. Hit the screen – this is really what the frames do. The projected frames hit the screen.” Peter Kubelka, “The Theory of Metrical Film,” in The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticism, ed. P. Adams Sitney (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1978), p. 139.

[48] Mann in Bitsch and Chabrol (Dundee trans.), p. 23.

[49] Nöel Burch, Theory of Film Practice, trans. Helen R. Lane (New York: Praeger, 1973), p. 126.

[50] James A. Sherlock, “Composition is Simple – Perhaps – But Very Important,” American Cinematographer 21, no. 1 (1940): p. 28.

[51] F.W. Pratt, “Pictorial Cinematography,” American Cinematographer 26, no. 8 (1945): p. 260.

[5] Howard T. Souther, “Composition in Motion Pictures,” American Cinematographer 28, no. 3 (1947): p. 85.

[53] Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 57.

[54] Immanuel Kant, Critique of the Power of Judgment, trans. Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews (1792; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), pp. 140-143.

[55] Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), in Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology: A Film Theory Reader, ed. Philip Rosen (New York: Columbia, 1986), p. 200.

[56] Burke, pp. 122-123.

[57] Compare Stephen Prince, Classical Film Violence: Designing and Regulating Brutality in Hollywood Cinema, 1930-1968 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2003), p. 288: “Filming and editing violence is tremendously exciting for moviemakers, and this pleasure is lodged at the most immediate and basic level of their craft.”