In an early scene from Medium Cool (1969) a television cameraman, John (Robert Forster), and his sound recordist, Gus (Peter Bonerz), visit Resurrection City, a temporary shantytown erected on the Washington Mall in May of 1968. The soundtrack for this sequence features the protestors’ performance of the gospel song, “This May Be the Last Time,” and it synchronises well with Haskell Wexler’s depiction of the Poor People’s Campaign. Yet even as a reality effect takes hold, a sly incongruity rears its head for those familiar with Wexler’s earlier documentary film, The Bus (1965). In fact, the audio recording for this particular song was first used in the latter film, captured during its coverage of “The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” which famously occurred on August 28th, 1963. The repurposing of this recording in Medium Cool, as Gus and John make their way among the occupied tents, could be taken as a nod to Wexler’s earlier work and as a reminder of the filmmaker’s grounding in the documentary tradition. It could even be suggested that the use of this audio recording in 1968 expresses a lineage between these two seminal historical events and their shared contribution to the long struggle against racial and economic inequality. However one is inclined to read this sonic overlap, it does serve as a reminder that Wexler’s embrace of a véríté-style documentary practice tends to tease historical significance out of the everyday. And, as such, it serves as a useful entry point into my reading of Medium Cool against the background of shifting documentary styles. Certainly, The Bus is often overlooked both as an important document of the Civil Rights movement and as a template for Wexler’s range of cinematographic approaches. The film is a travelogue that tracks the journey of Civil Rights activists from California to D.C. for Martin Luther King Jr.’s historic march. And with this film and its entanglement with Medium Cool as our lens, I will argue that the plurality of 1960s documentary impulses present in both films not only imbues véríté with a deep sense of historicity, investing the intensities of daily experience with the socio-historical weight of decolonisation, but also tracks a shifting politics of white allyship. The way in which Wexler’s camera shifts from passive observer to instigator to object of derision and confrontation reflects the multifaceted role of the documentary lens in the sixties as well as an increasing sensitivity on the part of the documentarian that their presence matters, as a witness, as a participant, and ultimately as an enabler. As Wexler himself maintained, his “strongest background is in documentary” and reading Medium Cool alongside The Bus will help us shed light on the range of documentary stances adopted in both films as well as their politics.[1]

While Medium Cool is generally well known and admired for its hybrid mixture of narrative and documentary filmmaking, an opportunity remains to more fully consider the film from the vantage point of the latter. No doubt, there are multiple ways to approach this historic film. But my own teaching and research on documentary filmmaking suggests that critically assessing Medium Cool as we bear in mind broader shifts in documentary prevalent at the time can yield new insights into the film’s power and ongoing relevance to radical media cultures. By adopting this particular frame of reference for Medium Cool and Wexler’s previous work, my aim is to bring to the fore a historically specific structure of feeling within the North American documentary tradition that highlights a self-conscious politics of white allyship and solidarity. This will speak to the fact that Wexler’s use of the camera in both films is racially inflected, self-conscious and ultimately an extension of Wexler’s political awareness of himself as a sympathetic outsider, juggling the dialectics of allyship. Within this specific cultural formation, the documentarian and their film practice anxiously and doubly register their own awareness of privilege as well as their desire to participate in authentic social change. In his book, Black Bodies, White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race in America, George Yancy pinpoints this dilemma for white allyship when he observes that “[t]o be white in America is to be always already implicated in structures of power, which complicates what it means to be a white ally (or alligare, ‘to bind to’). For even as whites fight on behalf of people of colour, that is, engage in acts that bind them to people of color, there is also a sense in which whites simultaneously ‘bind to’ structures of power.”[2] Kris Sealey succinctly characterises the situation as a “double bind” in which white allies must reckon with an “ownership (and not disavowal) of one’s white identity.”[3] This ethical stance is evident in the shifting uses of the camera in The Bus and is even more emphatic in the narrative and cinematographic style of Medium Cool. Specifically, I seek to demonstrate how this politics of allyship and solidarity transitions from that of romantic observation to critical reflexivity, with a fuller sense of the above “double bind” evident in the 1968 film.

The Participant Observer as Romantic Ally

Approximately three months before Wexler began filming The Bus, another American filmmaker, George C. Stoney, was grappling with the limits of conventional documentary filmmaking in the wake of the upheavals of the ’60s. Stoney was at this point a well-established documentarian, especially as a consequence of his classic film All My Babies (1952). This film followed several years of Stoney’s work with the Southern Educational Film Production Service (SEFPS), where he produced films on mental health and social services, and it secured Stoney’s place as a highly sought after producer of sponsored, nontheatrical films. Nevertheless, as I’ve detailed elsewhere, by the early ’60s Stoney found himself lamenting in a letter to a friend dated 10 May 1963 that, as a documentarian, he felt unable to fulfil what he perceived to be his social and political obligations.[4] Even as the struggle against racial desegregation and inequality was advancing, Stoney’s self-perception – as indicated in the letter – is that he is merely “making a living … supporting the status quo … and failing in my basic responsibility to record history as it is made.”[5] Haskell Wexler directly echoes Stoney’s comments five years later in an interview with Film Quarterly, noting that he had been “interested in the civil rights movement … had worked in the South a long time ago, [but] had not done anything except follow the box score, so to speak. I thought the best way for me to re-acquaint myself with what the young people were doing, what was going on, was to make [The Bus].”[6]

Wexler’s pivot towards the production of The Bus is, then, animated by a similar sense of disengagement from the struggles for racial equality that were so prominent at the time. And the deferential stance conveyed in the statement above aligns with the sensibility and style of the film itself. To a substantial degree, The Bus adopts an observational approach associated with American direct cinema and at least superficially performs the act of acquaintance desired by Wexler. The politics of the film are couched in this sense of allyship, of getting off the sidelines while at the same time acknowledging one’s outsider status. Stoney himself noted, many decades later, that documentary filmmaking was ultimately reinvigorated by this “new approach (‘direct cinema’) … [which] inspire[d] us and refresh[ed] our resolves.”[7] I believe that The Bus offers us an opportunity to cement a deeper understanding of the observational mode of documentary filmmaking as well as underscore the significance of Medium Cool‘s own observational and reflexive dimensions. The caricature of the “fly-on-the-wall” stance associated with direct cinema can be enriched by accounting for these sensibilities of acquaintance, re-invigoration, and allyship. The dialectical implications of allyship, in which deeply held aspirations to assist in the struggle against racial inequality are wedded to a reflexive acknowledgement of one’s privilege, are partly mirrored in the observational dynamics at work in Wexler’s The Bus. Put bluntly, the film often traverses the line between insider and outsider while skirting the reality that one’s position mitigates one’s participation. On the one hand, the deference of what Wexler characterises as a véríté approach aims to yield to the pro-filmic realities caught by the cinematographer and sound recordist. The self-awareness that the filmmaker brings, as one that is in the process of “re-acquainting” oneself to a movement, prompts a kind of bearing witness and openness to learning that is very much in the moment. This speaks to the process of observing and familiarisation highlighted by Wexler in which the outsider yearns to be an insider. And yet, as one views The Bus, it is impossible to not also minimally acknowledge or recognise the active cultivation on the part of the film crew of this experience of witnessing. Whether such awareness is activated by moments of interaction between the subjects of the film and the crew or simply by a hurried swish pan, the implied passive stance of the film’s observational approach is nevertheless enabled by the participatory labour implied by the work of being present in the space and time of the protest and its organisation. The contours of observation and participation are thus interrelated in The Bus, but a fuller reckoning with the filmmakers’ positionality and Yancy’s double bind is nevertheless lacking. After all, an implication of seeing this film as an act of acquaintance is that it represents a starting point and as such a thorough engagement with the binaristic mandate of white allyship is ultimately fleeting. The limited vantage point of the film is one that is intimate with the activists featured, demonstrating a filmic allyship where witnessing is articulated alongside a romantic presence that is not yet equipped to acknowledge its own powers.

These characteristics of the film’s allyship are evident early on in The Bus as the audience is greeted by the historical marker of “August 1963.” This minimal title bears historical weight without the need for any elaboration given the significance of the march it seeks to document. In doing so, the film primes us to appreciate the social and historical significance of the quotidian scenes about to be furnished. And such an opening resonates with Stoney’s stated desire to “record history as it is made” in that it immediately blurs the line between the present tense disposition of the observational lens (recording “live” scenes as they unfold in front of the camera) and the future tense value of these scenes as recorded history. And the filmmakers’ sense of allyship and solidarity in this historical endeavour is conveyed in the first scene. It is one of the few where Wexler and his production team are directly acknowledged by the subjects of the film, who position themselves as historic white allies of the fight for racial equality. The romantic welcome the film crew receives is, to some extent, facilitated by the address of one white ally to another. In the first shot a white man (Charles Franklin) emerges onto a balcony of a home in northern California, peers down at the camera, and issues an invitation to “come on up” after noting that Wexler and his team are the “people that take the pictures.” While remaining out of frame, the film crew of Mike Butler, Nell Cox, and Wexler introduce themselves to the family of Polly, one of the members of the California delegation to the March on Washington. As one of the few “self-conscious” scenes in the film, Wexler is doubly acknowledged as a fellow white ally as well as an outsider as he and his crew of Butler and Cox are welcomed into the Franklin home and in some ways equally welcomed into this small corner of the movement and the march itself. The scene is a mix of interaction and observation and, as the crew films Polly’s preparations for the trip, her mother relays the family’s abolitionist history on the soundtrack.

As far as walking for causes is concerned, it’s nothing new with our family. I remember my grandfather who was reared in Western Virginia before the Civil War always bragged that he had walked forty miles to vote against secession. My family were abolitionists there so we kind of feel … sympathy with this march on Washington. And that’s why I’m quite proud of the children and credit goes to the kids really for getting the money together and making the plans. When the children realised there was a possibility that they could go … they told other people [and] it began to snowball.

This opening paints a picture of white allyship on multiple fronts. Most striking is the hailing of the father from the balcony to the film crew, inviting them into the space of the home as well as into the intricacies of the trip’s planning. The warm introductions between the family, the crew, and other volunteers help secure a bond among them all and cultivate a vision of this historic event from below, from the vantage point of volunteers and organisers geographically distant from the nation’s capital. In fact, our brief glimpses of the exterior Californian landscape of the home, which is densely forested, already underscores this sense of distance. And, of course, the mother’s testimony above explicitly grounds her children’s white allyship within a broader family history that includes her own grandfather’s opposition to secession as a southerner as well as their abolitionist roots.

The portrait that emerges, then, is not only one of this particular family, but also that of the crew whose allyship is openly welcomed. The emphasis on the act of walking in particular, both in terms of the looming march to Washington as well as the grandfather’s forty mile walk to oppose secession, speaks to the power of being present and making the effort to mobilise oneself and others to fight racial inequality. This ethics of mobility carries over to Wexler’s cinematography, which is always on the move and explicitly tied to his own physical presence in the time and space of this small tributary of the Civil Rights movement. The mother’s testimony on the soundtrack, in the end, secures a historical sense of white allyship that frames the work of the present generation as well as Wexler’s crew. The urgency of the present moment, engaged through the observational stance of the film, is also historicised through the solicitation of commentary from the subjects filmed.

“Come on up!” Ally welcomes ally in The Bus (d. Haskell Wexler, 1963)

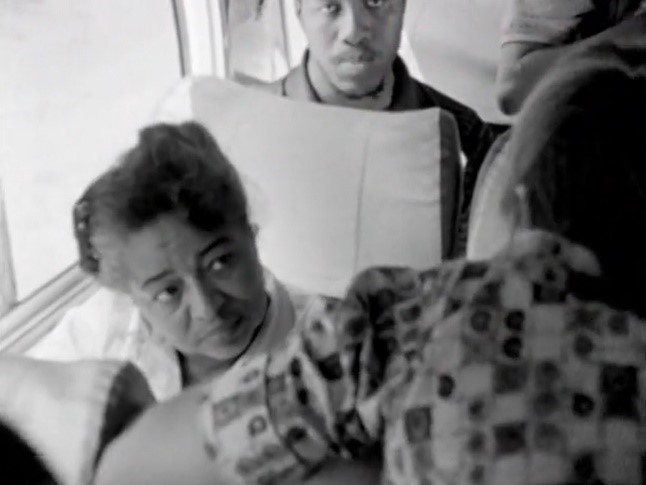

However, this opening scene soon yields to the diversity of the organising spaces of the California delegation, from a Baptist Church to the bus itself. Mobilisation emerges as a broader motif encompassing this interracial gathering of organisers and citizens as well as their physical movement through the West. The passage of the Lincoln Monument in Laramie, Wyoming stands out in this regard. The view of the bust of Abraham Lincoln perched on a granite tower denotes both the bus’s traversal through geographic space as well as the historical weight felt by the participants and implied by the film itself. As the exterior unfolds outside the windows, the depth of conversations evolves inside the bus, with exchanges between and testimonies from an array of personalities underscoring the significance of this historical moment. Most prominent are dialogues between African-American activists and supposed white allies, such as one featuring commentary from an African-American man explaining to two younger white men the appeal of nationalist movements and decolonisation in Africa. He insists that this appeal, the sentiment that “undergirds” such movements, includes a strong “pride of race and historical dignity [emphasising] that we are a people of destiny … [and] even the children talk this way.” The filmic coverage of this conversation grants prominence to the African-American man’s testimony as the white activists are shown listening at the margins of the frame (and sometimes slipping outside of the frame altogether). This contrasts with the tenor of a subsequent scene in which an African-American woman and a white woman are filmed debating nonviolence. Within the intimacy of the bus, the conversation is filmed entirely as an over-the-shoulder shot in which the face of the African-American woman is visible and often centred while the white woman is filmed from behind. This ultimately keeps our focus on the African-American woman’s facial expressions while the white woman shares her response and point of view. Throughout the conversation the African-American woman seeks to highlight the limits of nonviolence, and even its impracticality, when one is subject to the indignities and the explicit violence of prejudice and inequality. What if, she asks the white woman, “you are in a situation where someone is going to attack your husband … [or] to attack you? These situations occur. We see them in the paper every day. Would you stand by … or would you pick up the nearest stick at hand and bang the other guy over the arm, over the head?” The white woman can only respond that she “sincerely” hopes that were she ever in such a situation she would not resort to violence. The scene ultimately concludes with the African-American woman asking, “Well, what would you do?”

Interracial dialogue on the bus (The Bus, 1963)

“Well, what would you do?” (The Bus, 1963)

The tension in the above conversation represents a pivotal point in the film’s depiction of allyship. In the opening, the welcome issued to the camera crew originates from one white ally to another, albeit one whose familial history of abolitionism is reinforced through the commentary on the soundtrack. As the film documents the interracial mobilisation described above, the social space of the bus is depicted as a site of contestation where challenging interracial dialogues can be had. In particular, the possibilities and perils of white allyship run the gamut. First we receive the film’s depiction of the white positionality of engaged witness as the African-American man above insists on the pertinence of African nationalism and decolonisation for the Civil Rights movement. And, second, we observe a struggling instance of allyship due to a lack of self-awareness when the white woman implicitly admits that the scenarios described and endured by the African-American woman are, for someone with white privilege, essentially hypothetical and academic. These nuances should not distract from the film’s broadly observational and participatory stances. And, The Bus is fundamentally a romantic example of American direct cinema with all of the mixed modal tendencies that are the norm in documentary rather than the exception. The entirety of the film is energised by these overlapping observational and participatory postures and, as a result, the film retains a sense of spontaneity, a feeling of bearing witness to events unfolding in real duration. Hence the film is overwhelmingly presentist even as the mobile, active, observational camerawork is in some sense still historically conscious thanks to a deep sense of anticipation, of being proximate to a politically seminal event.

And yet the above failure of the white woman to fully reflect upon or acknowledge her own privilege in her conversation with the African-American woman is as indicative of the film’s perils as it is its powers. The film’s romantic posture of the observer-participant does not fully reckon with Yancy’s insistence on the double meaning of alligare. The welcome of one white ally to another at the outset enacts a mutual acknowledgement of social responsibility without the critical ricochet of reflection on their own privileged racial position. This introduction is coextensive with the mother’s nostalgic reflection on her family’s history that, while admirable, too easily skirts questions of culpability particularly when the film opens with a white liberal perspective. By hedging on the double bind of allyship, The Bus simply registers the contributions and limitations of a romantic observational travelogue produced from the vantage point of an outsider yearning for connectivity and acquaintance with the Civil Rights movement. Nevertheless, five years later, the inaugural gesture and the invitation of the crew into the home stands in fascinating contrast to the critical reflexive approach of Medium Cool, where the filmmakers and participants collaborate in the distinct historical coordinates of Chicago 1968.

White Man with a Movie Camera: Visitation, Reflexivity, and Verticality

The above sense of anticipation towards events of unique social and historical magnitude similarly structures Wexler’s 1968 film. In his seminal analysis of Medium Cool, Michael Renov acknowledges the unique way in which it unfolds towards an overpowering “historical milieu.” [8] He notes how the “fictionalised, foregrounded action is progressively undermined and at last inverted.”[9] The key sequence as highlighted by Renov is Eileen’s (Verna Bloom) search for her son (Harold Blankenship), which “leads us from the provinces of the private and the fictional into the savage underworld of city streets and bloody confrontation.”[10] Both The Bus and Medium Cool, then, charge their narratives with a dramatic sense of building towards a climax that overwhelms and disperses the featured personalities. While the former emphasises the work of mobilisation in support of a planned event in Washington, the latter is shaken by the infamous crackdown on the part of the Chicago Police Department. The specific geographies of Washington in 1963 and Chicago in 1968 are both centres of historical gravity that envelop and subsume the individuals we’ve come to know. In this way, the observational and interactive modes deployed in these films are charged with a sense of anticipatory momentum, building towards significant and explosive historical events. Indeed, for Renov, Wexler’s background in documentary as well as “his preoccupation with film as a political tool” grants a unique “autonomy” to the “historical ‘real’ ” – one that ultimately overwhelms “certain fundamental narrative aims, particularly that of closure.” [11]

These broad strokes of similarity between The Bus and Medium Cool should not distract from their differences. Beyond the obvious and reductive distinction that the former is “nonfiction” and the latter is essentially “fiction,” Medium Cool’s famously politicised reflexivity also appears anew when approached through the lens of The Bus. In fact, the romantic observational ethos present in The Bus shifts in Medium Cool towards a critical and reflexive vision that forges a critique of white allyship, a more radical acknowledgement of the complicity of the participant-observer. In this manner Medium Cool animates a broader political critique of the documentarian’s boundary crossing and implicit entitlement to the lives of others. The emphasis on John as a broadcast journalist ultimately positions the cameraperson at the endpoint (or starting point) of a systemically racist political economy. In such a context, the notion of allyship is compromised by the unwitting ways in which John participates in the daily surveillance and violence that is brought to bear on Chicago’s African-American residents.

Most notable, from this standpoint, is the way in which one of Medium Cool‘s most famous scenes inversely rhymes with the opening from The Bus discussed earlier. As we saw in the latter, a white ally welcomes another white ally. But in Medium Cool the warm greeting of “Come on up!” has been replaced by a more circumspect observation delivered on one side of a closed door by a Black radical (played by Jeff Donaldson): “We have a visitor.” In this seminal scene, John and Gus visit a Black neighbourhood to find Frank Baker (Sid McCoy), a cabbie who returned a large cash sum ($10,000) that had been left behind by a passenger. Their hope is to persuade Frank to participate in a “human interest” story about the episode for a local television news station. As John and Gus venture into the community and eventually into Baker’s home, the alignment between the protagonists and the filmmakers swells with both clarity and significance. Indeed, the reflexivity of Medium Cool is, to some extent, anchored by the synchronicity between John’s profession as a camera operator and Haskell Wexler’s renown as a cinematographer. Renov recognises this alignment in his own writing on the film when he notes the “recurrent play of identity between protagonist and filmmaker.” [12] This scene famously plummets into a confrontation between the “Black militants” in Baker’s apartment and the news crew, eventually toppling the comfortable observational stance of the non-diegetic camera. At this point, the implicit parallel between the diegetic production team and Wexler’s crew is reflexively acknowledged through the use of direct address from two African-American men to the camera and the audience. The first monologue, delivered in an intimately framed medium close-up while making eye contact with the viewer, is as follows:

When you come in here, and you say that you’ve come to do something of human interest, it makes a person wonder whether you’re going to do something of interest to other humans or whether you consider the person human in whom you’re interested. And you have to understand that, too. You can’t just walk in out of your arrogance and expect things to be like they are, because when you walked in you brought in LaSalle Street with you, City Hall, and all the mass communications media. And you are the exploiters, you’re the ones who distort and ridicule and emasculate us, and that ain’t cool.

Here the romantic notion of white allyship is confronted with what Yancy insists is a bind. Of course, our view of John is already cynical in light of the film’s introduction when we witness him cavalierly collect footage of a fatal car crash, only suggesting that someone call an ambulance as an afterthought. And yet this moment at hand cuts deeper by challenging the camera’s presence in the time and space of an African-American home. John is no white ally, but the direct address has the effect of both calling that out as well as prompting a consideration of the endeavour of the film itself. The very act of entering the space of both the neighbourhood and Baker’s home (“You can’t just walk in …”) is questioned. The easy welcome of Charles Franklin in The Bus offers a portrait of white allyship that does not, and perhaps could not, highlight the stakes of crossing a threshold in this manner. The direct address prompts diegetic and non-diegetic reflections on this racialised threshold and the insistence on the part of the white protagonist as well as the white media establishment to bulldoze into such spaces without acknowledging the historical legacy of their presence, to recognise the separation as well as the connection. Actor Jeff Donaldson’s delay in opening the door at the beginning of the scene represents a call to reckon with the implications of such a boundary crossing. The hesitation itself frustrates narrative progression, John’s pursuit of a “human interest” story, as well as the impulse to document. Again, the romantic observational approach of The Bus must now be earned. The above monologue, in fact, questions the presumed humanist ethos of portraiture. In the inertial rush to record, does the filmmaker consider the implications of their actions, even as – or especially as – a white ally? Have they fully grappled with the question of whether or not they “consider the person human in whom [they are] interested”?

The quick transition to the second monologue represents a tonal shift in voicing and performance style. The speaker, a young African-American man (Felton Perry), is similarly framed in a medium shot, but his address to the camera is much more heightened and exclamatory as he calls out the news media for its privileging of violent spectacle over both systemic and quotidian realities. As John himself notes early in the film, the media does not “deal with the static things. We deal with the things that are happening. We deal with the violence. Who wants to see somebody sitting?” As if in response to this earlier statement, the speaker here passionately details the cost of this approach.

You don’t want to know, man. You don’t know the people. You don’t show the people, Jack. I mean, dig, here’s some cat who’s down and out, you dig? … One hundred million people see the cat on the tube, man. And they say, “Ooh, the former invisible man lives!” Everybody knows where he went to school. They know about his wife and kids, everything. Because the tube is life, man. Life. You make him an Emmy, man. You make him the TV star of the hour, of the six, the ten, and the twelve-o-clock news. ‘Cause what the cat is saying is truth, man. Why don’t you find out what really is? Why do you always got to wait ’till somebody gets killed, man? Because somebody is going to get killed.

The news-gathering posture characterised and rationalised by John is implicated here in the very violence it purports to record. Visibility is a trap, conferring a public life in lieu of substantive forms of social redress. And John’s claim to have the interests of his subjects in mind is called out as false, as a disavowal of the role he plays in perpetuating forms of surveillance, harassment, and oppression on the South Side. His form of allyship is directly critiqued as mere posture, one designed to find the next “TV star of the hour” before dispensing with them and repeating the cycle all over again. This scene arguably romanticises a distinction between documentary cinema and television (favouring the former over the latter). Nevertheless, such a self-congratulatory reading of the scene is too neat and leaves aside the emphasis placed on the direct address to the camera as well as the inevitable racialisation of the production process as a whole. The critique cannot be contained in the above manner and the reflexivity reaches far and wide, ultimately confronting whoever wields the camera with their privileges and responsibilities.

In fact, the cut that abruptly takes us to the above monologues is preceded by an intensifying interracial argument between John and multiple associates of Baker’s, one of whom is an actress (Val Ward) voicing criticism of the narrow perspective of the white news media (“You people are always busy putting your kind of people on and what you want. So I want to talk to you about what I want.”). An intervention by another militant thwarts a physical confrontation (“I just saved your life. You understand that, don’t you?”) and redirects the dialogue towards a more profound intercession.

Militant: You came down here to do some sort of jive interview. You did that. Came down here with 15 minutes of a Black sensibility. And so you don’t understand that. You came down here to shoot 15 minutes of what has taken three hundred years to develop. Grief, you know?

John: Look, I’m not interested in grief.

Militant: And all we’re trying to explain to you is that you don’t understand.

John: I do something. You see, I do it well. That’s my job.

Militant: No, but you don’t do it Black enough. You can’t, because you’re not Black.

In this context, the subsequent Brechtian shift to direct address is rationalised without undercutting its impact. The pivot towards self-referentiality in this particular scene reflects in microcosm the broader contours of the film’s blend of fiction and nonfiction. Renov’s above recognition that the “fictionalised” dimensions of the film are gradually or “progressively undermined and at last inverted” is wholly in force here as the scene unfolds from beginning to end. But in place of the film’s inevitable tumble towards a traumatic historical horizon, this scene specifically transitions into a confrontation with the reality of the white production itself. Some of the strongest features of both The Bus and Medium Cool include the prominence given to difficult interracial conversations. This scene is the penultimate example not only because of the intensity and honesty of the conversations involving John, but also because of this reflexive swivel towards the constitutive and deeply racialised relationship between the subjects of the film and the production itself.

“We have a Visitor” (Medium Cool, 1968)

“You can’t just walk in out of your arrogance and expect things to be like they are…”

“You don’t want to know, man. You don’t know the people. You don’t show the people, Jack.”

The aforementioned hesitation as John the visitor knocks on the door marks a pivotal moment in John’s gradual recognition of his own complicity in a broken system by virtue of doing his job “well.” But its impact is more than this as the hesitation bolsters this scene’s reflexive commentary on the politics of production and reception. In other words, this is a productive instance of wavering that recognises the limits of Wexler’s own perspective as the writer, director, and cinematographer of the film. This is even evident in the scene’s production history as presented in Paul Cronin’s documentary, Look out, Haskell, It’s Real!: The Making of Medium Cool (2001). Here Jeff Donaldson, a visual artist and writer who plays the Black militant that greets John when he enters the apartment, recounts that the scene was inspired by an activist intervention at a conference hosted by Columbia College Chicago. Like other cultural institutions around the country in the late ’60s, Columbia College embarked on a series of initiatives to reach out to Chicago’s African-American communities in light of the run of urban rebellions in cities such as Watts, Detroit, and Newark. Historian Paul Siegel notes: “[T]hey brought in people from all over the country to talk about their experiences in their areas and things that might be done in Chicago. They had not invited any one from the Chicago cultural community to participate in this conference, people who had, over the years, been active in the arts in the community.” [13] In response, Donaldson and other local African-American artists set out to “crash” the conference and the conversations that took place inspired Wexler to include a similar scene in Medium Cool. [14] According to Donaldson, Wexler “had seen the confrontation we’d had with the people from Columbia College and had wanted to do something that would show [what] was going on. He wanted us simply to say whatever we wanted to say about what was going on in the community.” [15] Indeed, while filming the scene itself there was a clear sense of collaboration and this carried over into post-production as well. Participants in the scene, Felton Perry and Muhal Richard Abrams, both commented that improvisation was encouraged by Wexler and even insisted upon by the actors. Abrams himself states that they “wouldn’t have consented to be a part of it unless we improvised. I think most of us were very aware and cautious about anyone putting words in our mouth, especially during that time.” [16] Paul Golding, an editorial consultant on the film, notes in Cronin’s film that this was the “first completed scene that we did” and the activists’ and artists’ “deal with us was, ‘We’ll let you use what you shot of us if we can see and approve.'” [17]

The above approach echoes the contemporaneous documentary style of Canadian filmmaker Colin Low, whose brand of “vertical,” participatory documentary production had been imported to the United States in 1968 and 1969. Low, in fact, worked with Verna Fields, the editor of Medium Cool, during this time as an editorial consultant on a series of participatory documentaries produced for the Office of Economic Opportunity, set in Farmersville, California and Hartford, Connecticut (the latter included collaboration with Charles “Butch” Lewis, founder of the city’s chapter of the Black Panther Party). [18] According to Low, vertical films oppose the horizontality of traditional documentaries because the latter over-emphasize the authorial perspective of the filmmaker, who syntagmatically arranges sights and sounds for the viewer. Instead, verticality tips the scales towards shorter works of portraiture that privilege the voices and perspectives of the subjects filmed and, by virtue of their lack of broader exposition and narrative context, mitigate the filmmaker’s authorial control. [19] Furthermore, the production of such vertical films often entailed what is a key component of the Fogo Process, namely the solicitation of feedback from the subjects filmed to ensure that it accurately represents their experiences and perspectives. Although Medium Cool is a feature film, Wexler’s approach hedges on horizontality and incorporates aspects of this vertical style. In fact, another way to characterise the above scene’s evolution into direct address is to see it as a transition from horizontality to verticality. Just as John eventually dissolves out of the frame, so does Wexler concede some degree of control through the participatory approach reviewed above (in which collaboration traversed multiple production stages). This semblance of verticality demonstrates the wisdom of hesitation and the need to withhold narrative or expository momentum in order to privilege voices that are typically not heard from in the mass media. Such a stance is evident in the observational ethos of The Bus, but is ultimately rendered more radical and reflexive in Medium Cool. The true double bind of white allyship is more closely expressed in Medium Cool through such vertical visions as those rendered above.

This vertical sensibility also highlights Medium Cool’s relevance for contemporary media activists. In Medium Cool Revisited (2013), Wexler documents a series of protests and speeches given at the 2012 Chicago Summit (May 20-21), a gathering of the heads of state of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). The 38th G8 Summit had been scheduled to coincide with the NATO meeting, but was moved to Camp David largely out of concern for such protests. Throughout the short documentary, Wexler is visible onscreen interviewing activists and his voice can be heard on the soundtrack commenting on the historical parallels between the protests at the Chicago Summit and those that subsumed his film at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. In fact, Revisited visually advances this thesis by juxtaposing scenes of contemporary protest footage with those from his classic film, illustrating the ongoing nature of what Wexler characterises as the “struggle” in the closing moments of this documentary. Such commentary and Wexler’s overall presence, even being filmed with his digital camera in the streets, reflects an ethos of allyship that blends the romantic observation of The Bus with the critical reflexivity of Medium Cool, even showcasing the ways in which present day forms of counter-surveillance, or sousveillance, entangle active witnessing with critical self-knowledge. Low’s above preference for a deferential style that keeps our focus on the contingent realities recorded rather than on an over-arching narrative or expository frame rhymes with this activity while being conjoined with, following Yancy, an awareness of one’s ever-present “implication” in the structural conditions that foster inequality and injustice. The clips of Medium Cool presented here strip away the narrative and help us pinpoint this classic’s significance for contemporary radical media cultures.

This final point perhaps takes to heart the rhetorical indulgences of Vincent Canby when he declared that Medium Cool “offered a picture of America in the process of exploding into fragmented bits.” [20] This quote references the film’s depiction of racial struggle and social protest, but it also inadvertently encapsulates its latent verticality and embrace of disturbance as a key component of the film’s reflexive politics. The romantic observation of The Bus and the welcome of one white ally to another is ultimately insufficient as a media activist practice. But by the late ’60s, as historical conditions and Wexler’s own film style evolved, the terms of allyship have changed and a fuller sense of alligare is realised through an embrace of critical reflexivity. Of course Medium Cool is a film that is of its time, a fact that speaks to its merits as well as its challenges. Even Medium Cool Revisited is limited by its nostalgia for the earlier feature and both centre themselves on the perspectives of white protagonists with access to the means of production. And yet Canby speaks of Medium Cool‘s documentation of a “process” and this term also speaks to the film’s position within a particular genealogy of media activism in which social movements increasingly take advantage of greater access to such means, no longer subject to processes of collaboration or confrontation with outsiders equipped with cameras. Transnational media activism is frequently vertical in disposition and toggles between the various postures of witnessing, inciting, participating, and informing. In this sense, the values of allyship and acquaintance embodied by these two seminal films of Wexler’s reflect their historical moment while also helping us make sense of our present circumstances where participatory media ethics are still so inescapably vital.

Notes:

[1] “Haskell Wexler on Medium Cool Ð Conversations Inside the Criterion Collection,” YouTube video, 15:00, posted by Vice, September 7, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v7qMNXu2dXQ

[2] George Yancy, Black Bodies, White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race in America, 2nd edition (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), pp 226.

[3] Kris Sealey, “Transracialism and White Allyship: A Response to Rebecca Tuvel,” Philosophy Today 62, no. 1 (Winter 2018): pp 27.

[4] See Stephen Charbonneau, Projecting Race: Postwar America, Civil Rights, and Documentary Film (Wallflower Press, 2016): pp 78.

[5] Qtd. in ibid.

[6] Ernest Callanbach, Albert Johnson, and Haskell Wexler, “The Danger is Seduction: An Interview with Haskell Wexler,” Film Quarterly 21, no. 3 (Spring 1968): pp 10.

[7] Jack C. Ellis, The Documentary Idea: A Critical History of English-Language Documentary Film and Video (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1989), pp 302.

[8] Michael Renov, The Subject of Documentary (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), pp 33.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid., pp 3.

[12] Ibid., pp 30.

[13] Qtd. in Haskell, It’s Real!: The Making of Medium Cool (d. Paul Cronin, 2015). This is from the expanded edition of Cronin’s film undertaken to coincide with the Criterion Collection’s release of the film in 2013. The transcript is available on Paul Cronin’s site, The Sticking Place, http://www.thestickingplace.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/LOHIR-dialogue-transcript.pdf. The relevant except of the 2013 version of Look Out, Haskell! It’s Real! (Part 3 of 6) can be viewed at: https://vimeo.com/showcase/2967272

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] See Charbonneau.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Vincent Canby, “Real Events of `68 Seen in ‘Medium Cool’: Haskell Wexler Wrote and Directed Movie,” The New York Times, August 28, 1969, https://www.nytimes.com/1969/08/28/archives/real-events-of-68-seen-in-medium-coolhaskell-wexler-wrote-and.html

Works Cited

Callanbach, Ernest; Albert Johnson; and Haskell Wexler. “The Danger is Seduction: An Interview with Haskell Wexler.” Film Quarterly 21, no. 3 (Spring 1968): pp 3-14.

Canby, Vincent. “Real Events of ’68 Seen in ‘Medium Cool’: Haskell Wexler Wrote and Directed Movie.” The New York Times, August 28, 1969. https://www.nytimes.com/1969/08/28/archives/real-events-of-68-seen-in-medium-coolhaskell-wexler-wrote-and.html

Charbonneau, Stephen. Projecting Race: Postwar America, Civil Rights, and Documentary Film. London: Wallflower Press, 2016.

Cronin, Paul. “Look Out, Haskell! It’s Real: The Making of Medium Cool.” Extended Cut.

Ellis, Jack C. The Documentary Idea: A Critical History of English-Language Documentary Film and Video. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1989.

“Haskell Wexler on Medium Cool – Conversations Inside the Criterion Collection.” YouTube video, 15:00. Posted by Vice, September 7, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v7qMNXu2dXQ

Kerner, Otto. The Kerner Report: The 1968 Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. New York: Bantam Books, 1968.

Newhook, Susan. “The Godfathers of Fogo: Donald Snowden, Fred Earle and the Roots of the Fogo Island Films, 1964-1967.” Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 24, no. 1 (2009): pp 171-197.

Renov, Michael. The Subject of Documentary. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Sealey, Kris. “Transracialism and White Allyship: A Response to Rebecca Tuvel.” Philosophy Today 62, no. 1 (Winter 2018): pp 21-29.

White, Jerry. The Radio Eye: Cinema in the North Atlantic, 1958-1988. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2009.

Wiesner, Peter K. “Media for the People: The Canadian Experiments with Film and Video in Community Development.” In Challenge for Change: Activist Documentary at the National Film Board of Canada, edited by Thomas Waugh, Michael Brendan Baker and Ezra Winton, pp 73-102. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010.

Yancy, George. Black Bodies, White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race in America. 2nd Edition. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.