Part 1 (1967 – 1969): My Beginnings – Producer, critic and educator Rod Bishop recalls his days at La Trobe University

Rod Bishop was the producer and co-writer of the restored and re-released (on Blu-ray) Body Melt (Brophy, 1993) and has also been a prominent critic, writer and educator. He was the Director of the Australian Film Television and Radio School from 1996 to 2003. Rod was recently invited back to La Trobe University in Victoria in 2017 to make a speech celebrating the University’s 50th anniversary since its establishment in 1967. This is Part 1 (1967-1969) of an expanded version of the talk.

Rod Bishop

1967. They say the first student intake at La Trobe University was 500 students, but it felt more like 200. There were only two buildings – Glenn College and the Library. To get to the car park, the new students had to walk from Glenn College and past the Library. One of my most cherished memories from that first year was seeing the esteemed Professor of Economics Donald Whitehead, standing outside the Library berating students on their way to the carpark for not coming inside to study.

We had a very good time in that first year. So good, it’s said two-thirds of us failed in at least one subject.

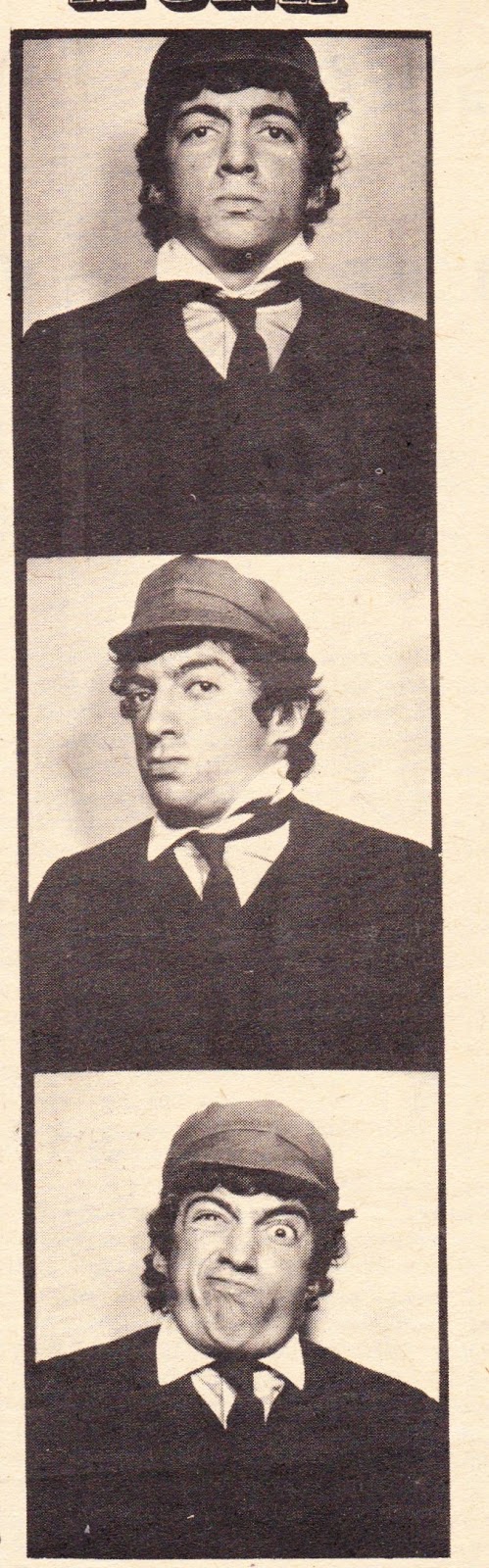

On that first day at La Trobe I saw a notice posted on the wall of Glenn College reading something like “Anyone who wants to help start a film society meet here at 5”. The motley group who turned up included Peter Beilby, with whom I am still good friends, and his mate Philippe Mora. A smallish but enormously energetic Bob Dylan lookalike, Philippe said “let’s all go back to my place for the meeting”. Philippe turned out to live in an Art Gallery and took his family meals in a restaurant – the Tolarno Art Gallery and Restaurant in Fitzroy Street, St Kilda. His mother was the extroverted painter Mirka Mora and his father was the suave Georges Mora, a man who’d fought for the French Resistance alongside the mime Marcel Marceau. Philippe’s parents served us French coffee, each cup with an individual filter, and talked to us like we were their equals. This wasn’t constricted, constrained and constipated Mont Albert anymore. I’d gone to a parallel universe and didn’t intend returning anytime soon.

Philippe Mora, 1967

In that first year, under Philippe’s influence, the film society became a force on campus. We even held a ‘Cinematheque Discotheque’, with 16mm projectors screening Metropolis (Lang, 1927) and Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein, 1925) onto screens above Jeff St John and The Id and Max Merritt and The Meteors. We had no forward planning and no idea how successful the event would be. The entrance money kept piling up on a table. Periodically one of us would take an armful of the stuff to a room in Glenn College, throw it on to the floor and lock the door.

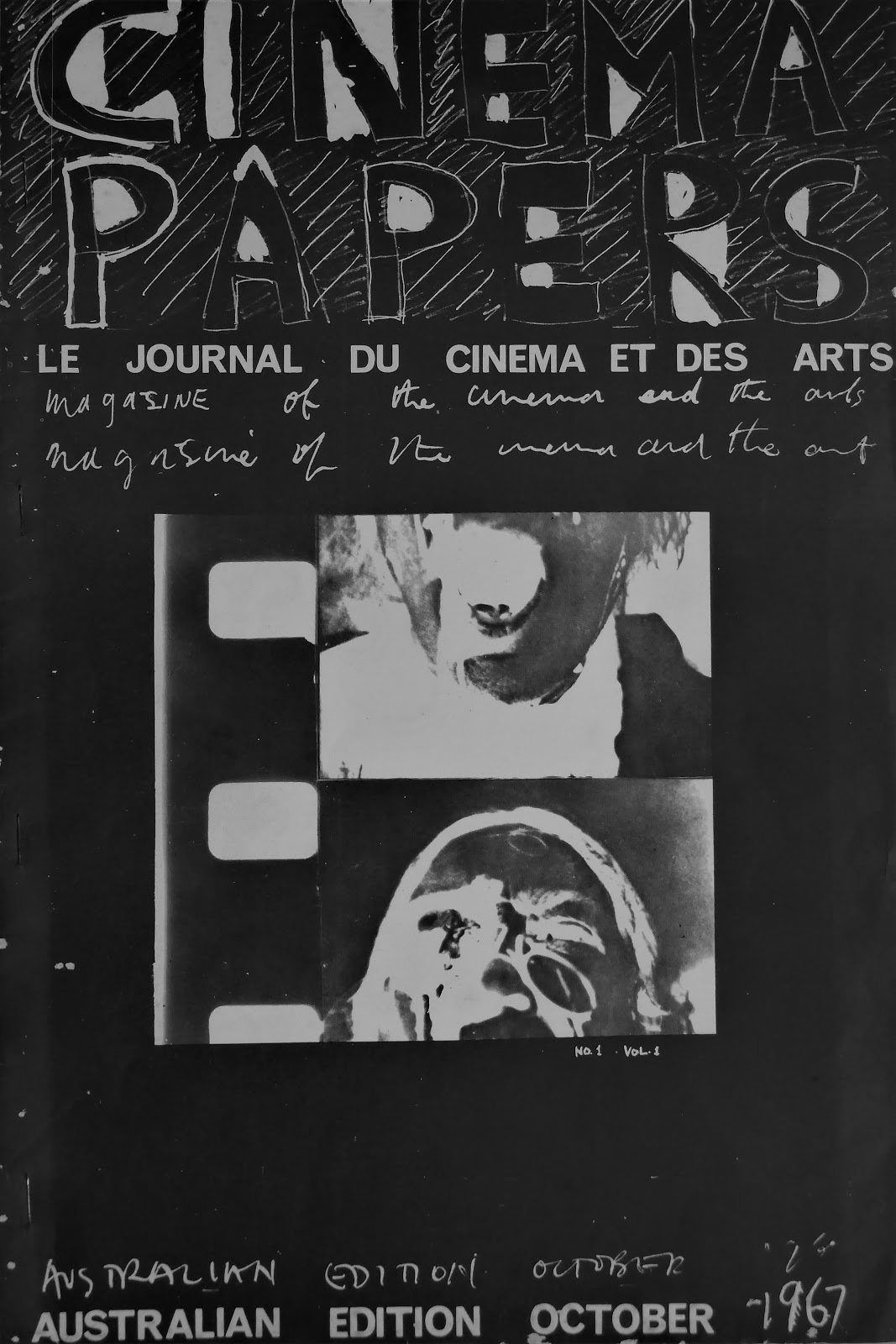

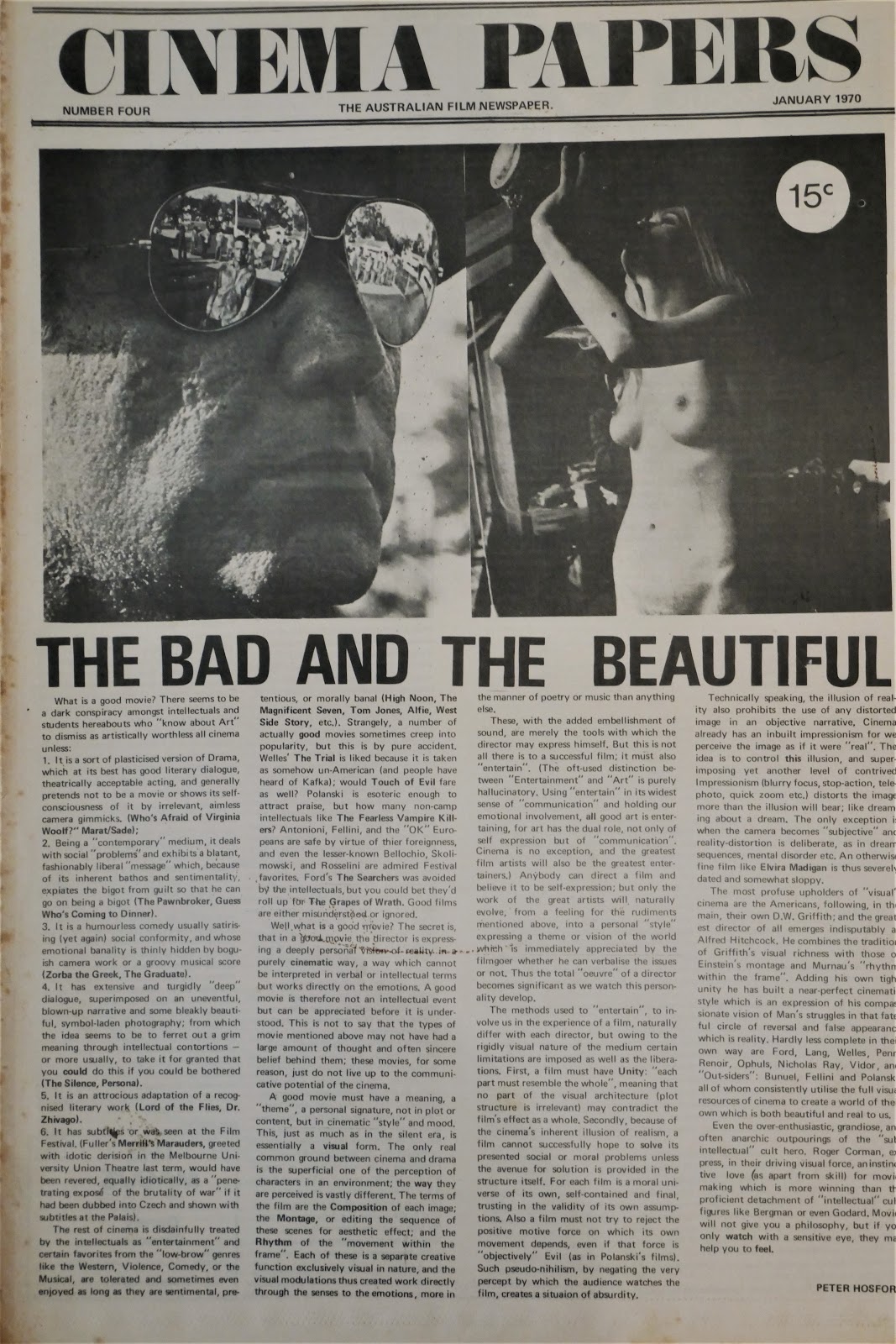

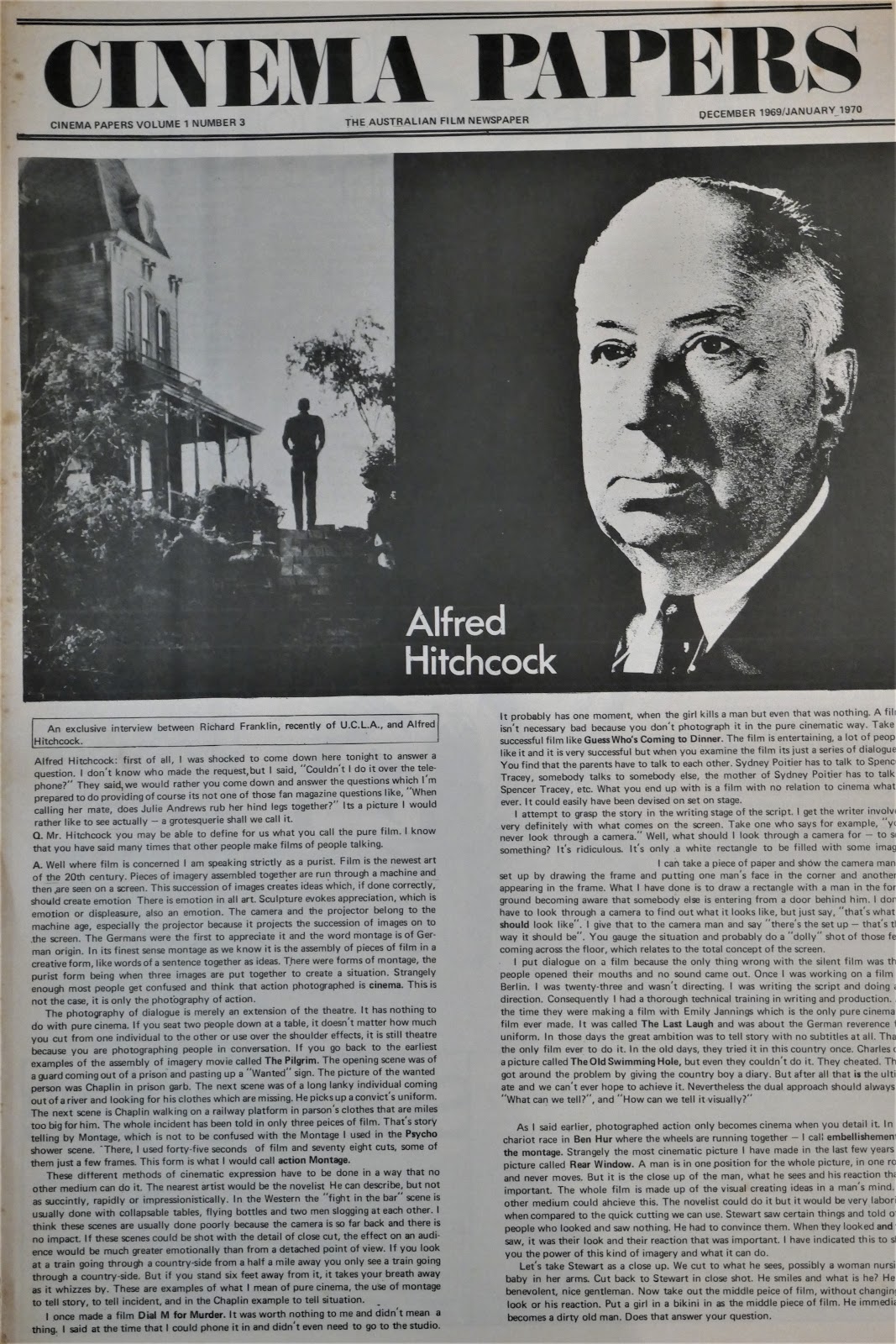

The film society published the first edition of Cinema Papers that year, edited by Philippe and Peter. It never would have happened without the help of Kay Mathews, a secretary in the Philosophy Department. Late at night, Kay let us in to the department to roneo-off the magazine using the department’s equipment and paper. Cinema Papers went on to become Australia’s leading film magazine for the next 30 years.

Around Glenn College, the Charismatic Ones were seen with import copies of ‘Are You Experienced?’ (Jimi Hendrix Experience, 1967))

Glenn College was a strange beast that first year. We were all expected to wear academic gowns in the cafeteria at night. It was part of something called The College Concept – borrowed from Oxbridge – where students would belong to one of ten colleges around the campus. There would be no central Student Union for students to congregate. As the legendary 1968 dawned, the College Concept seemed like a wrong idea at a very wrong time.

Cover of Cinema Papers, #1, 1967

1968 and the fun of the first year was over. It was now all about the War. Political clubs proliferated and you could almost see the political counter-culture form in front of your eyes. The Military Industrial Complex? Boo! Down with American Imperialism – hooray! When students walked out of lecture theatres where their ideas (and ideals) were constantly challenged by some very good teachers, they walked into a whirlpool of student activism. La Trobe become very radical, very quickly and stayed that way for the next five years.

The Charismatic Ones were seen on campus with import copies of ‘Music from Big Pink’ (The Band, 1968).

In September of 1968 Donald Chipp drew my birthday marble from a barrel and I was conscripted into National Service. Although automatically deferred until I finished my degree, I sent a letter to the Department of Labour and National Service informing them I had joined their growing list of Draft Resisters.

1969 and it was all about the War. But now the North were winning. As fellow student Martin Munz declares in Beginnings, a film I was to help make in 1970:

“Those people who are our powerful friends have lost…seems to me they’re finished…America’s going down…a country that can’t control internal dissension can’t maintain a strong foreign policy and that’s the only thing we care about…”

In his excellent book of the times Student Revolt La Trobe University 1967-1973 Barry York, who was jailed in 1972 for three months in Pentridge for his student activism, lists many of the student political clubs – Labour Club, Socialist Club, Anarchist Club, Liberal Club, SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), Democratic Club, Communist Club, Democratic Socialist Club. Their newsletters, often printed on a daily basis included – Libertarian Revolution, Flowering Rifle, Enrages, Moot Point, Liberty, Red Moat (that was the Maoists) and my personal favourite Red Atom from the Science Study Group.

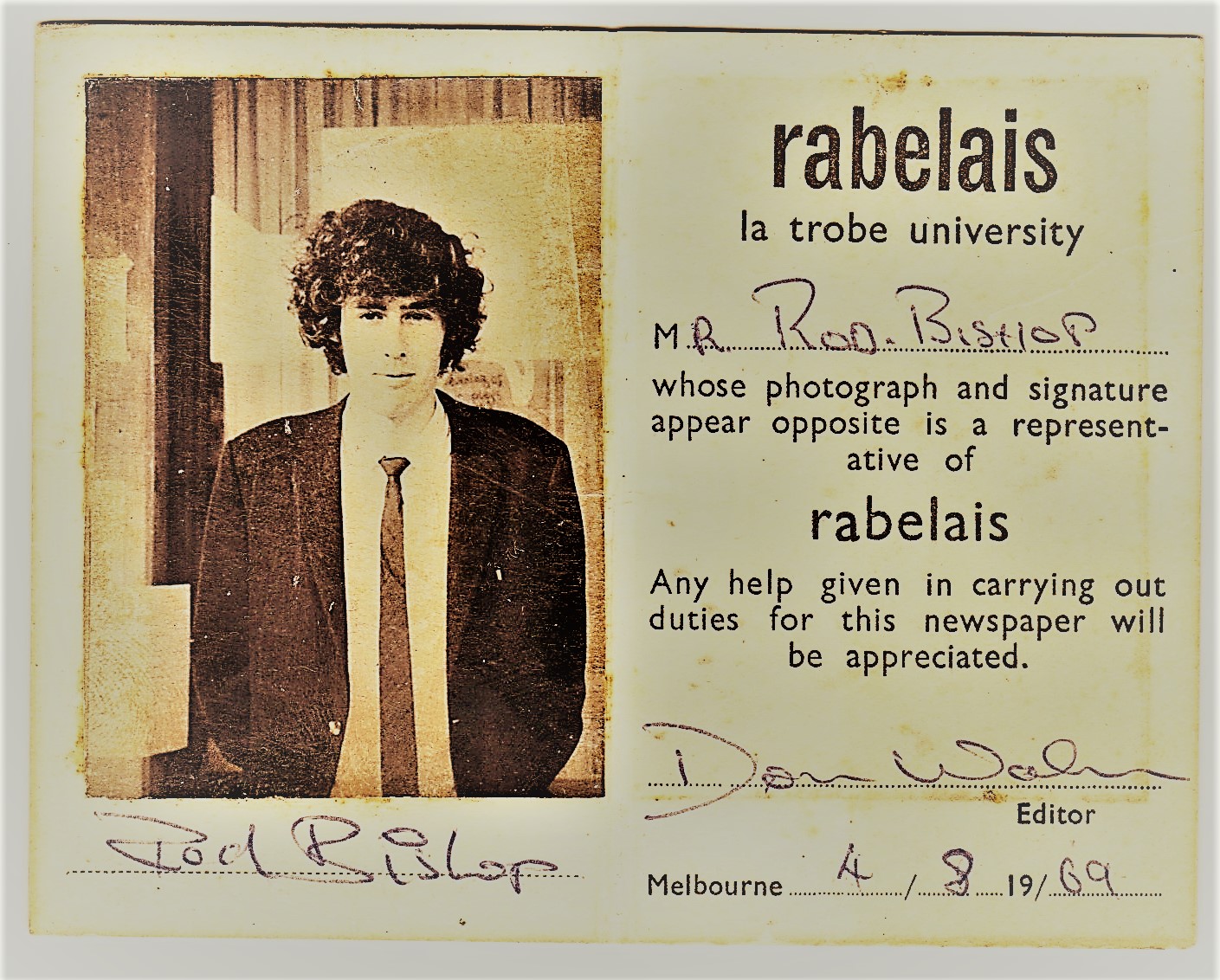

Rabelais Press Card, Don Watson Editor

That year, I co-edited Rabelais with Keith Robertson, another of the 1967 intake and still a good friend. We upped the political debate of the student newspaper and spent one entire edition demolishing The College Concept. In the end, only three of the ten colleges were built and La Trobe joined the rest of Australia’s universities in having a Student Union building. Fellow student Scott Murray, destined to be a later editor of Cinema Papers, contributed film reviews to Rabelais. Don Watson and David Loh edited the magazine in the second half of 1969.

The Charismatic Ones lost much of their charisma when no-one took much notice of their import copies of ‘The Flock’ (The Flock, 1969).

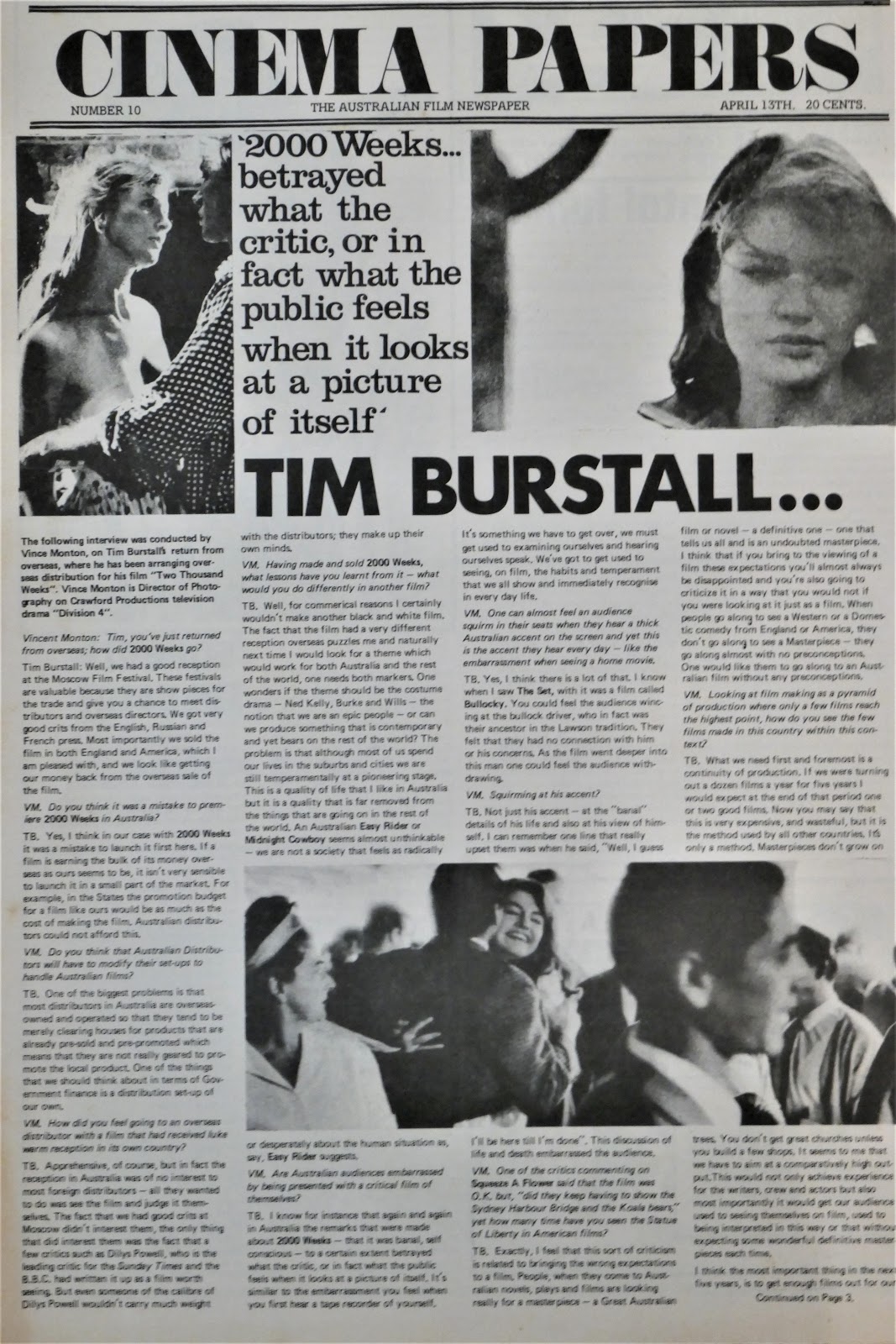

As the academic year wound down I joined the editorial board of Cinema Papers with Peter Beilby and Demos Krouskos to produce 11 fortnightly editions, entirely financed by advertising revenue and designed by Keith Robertson.

Front pages of Cinema Papers Number 1, 1969

Front pages of Cinema Papers Number 2, 1969

Front pages of Cinema Papers Number 3, 1969

Part 2: 1970: The Army Medical, Beginnings (1970), the Waterdale Road Massacre.

By 1970 there were estimated to be more than 1,500 draft resisters and conscientious objectors. I’ve never seen a figure for the numbers who ended up in jail, but I seem to remember the conscientious objectors were among the first targeted. La Trobe student Scott Murray, with whom I am still good friends, was a conscientious objector and was asked in court: “what would you do if a negro was attacking your mother?”

The government even jailed women from the ‘Save Our Sons’ organization. Their crime: distributing anti-conscription pamphlets on government property.

From Student Protest, Barry York’s history of La Trobe:

“In September 1970, the Department of Labour and National Service began its ‘law and order’ drive by issuing 50 summonses against carefully selected non-compliers. Four La Trobe students – Ian MacDonald, Shane Breen, David Loh and Rod Bishop – were victims, receiving notices to attend medical examinations”. (p.87)

Two former editors of Rabelais were in that group. I can’t remember who provided all the help – the ‘Draft Resisters Union’, ‘Youth Campaign Against Conscription’ or someone else – but their intelligence was exemplary. They were able to accurately inform draft resisters and conscientious objectors of the hours of the day when they were most vulnerable to be picked up. That meant going to a safe house before returning to campus. The information had to be coming from someone inside the Department of Labour and National Service and/or the police.

Arlo Guthrie, Alice’s Restaurant (Penn, 1970)

Eventually, we were offered “the Alice’s Restaurant option”. In Arthur Penn’s film from 1970, Arlo Guthrie attends his medical for the draft and through a variety of measures disrupts the process as much as possible. The tactic in Australia was based on draft resisters clogging up the medicals. If you ticked every box for every medical condition you were asked about, the doctor had to write down your case history (which you made up on the spot) for every single condition. It would take more than an hour, maybe two and disrupt the entire process. You ran the risk of being prosecuted for giving false information, but the advice coming back was the doctors would declare you medically unfit and move on to more co-operative conscripts.

My medical was held opposite the Hawthorn Football Ground in Glenferrie. Quite odd, as I am a lifelong Hawthorn supporter. Even stranger, my doctor was to be Doc Ferguson, the immediate past-President of the Club. In the waiting room (in our jocks), the bloke sitting opposite me looked exactly like Arlo Guthrie and had a ‘National Liberation Front’ badge pinned over his crown jewels. The clipboard we were given contained dozens and dozens of medical conditions – TB, polio, VD, asthma, cancer, diabetes – the list went on and on. I ticked them all and watched ‘Arlo Guthrie’ tick all his. He went in before me and didn’t come out for more than an hour and a half.

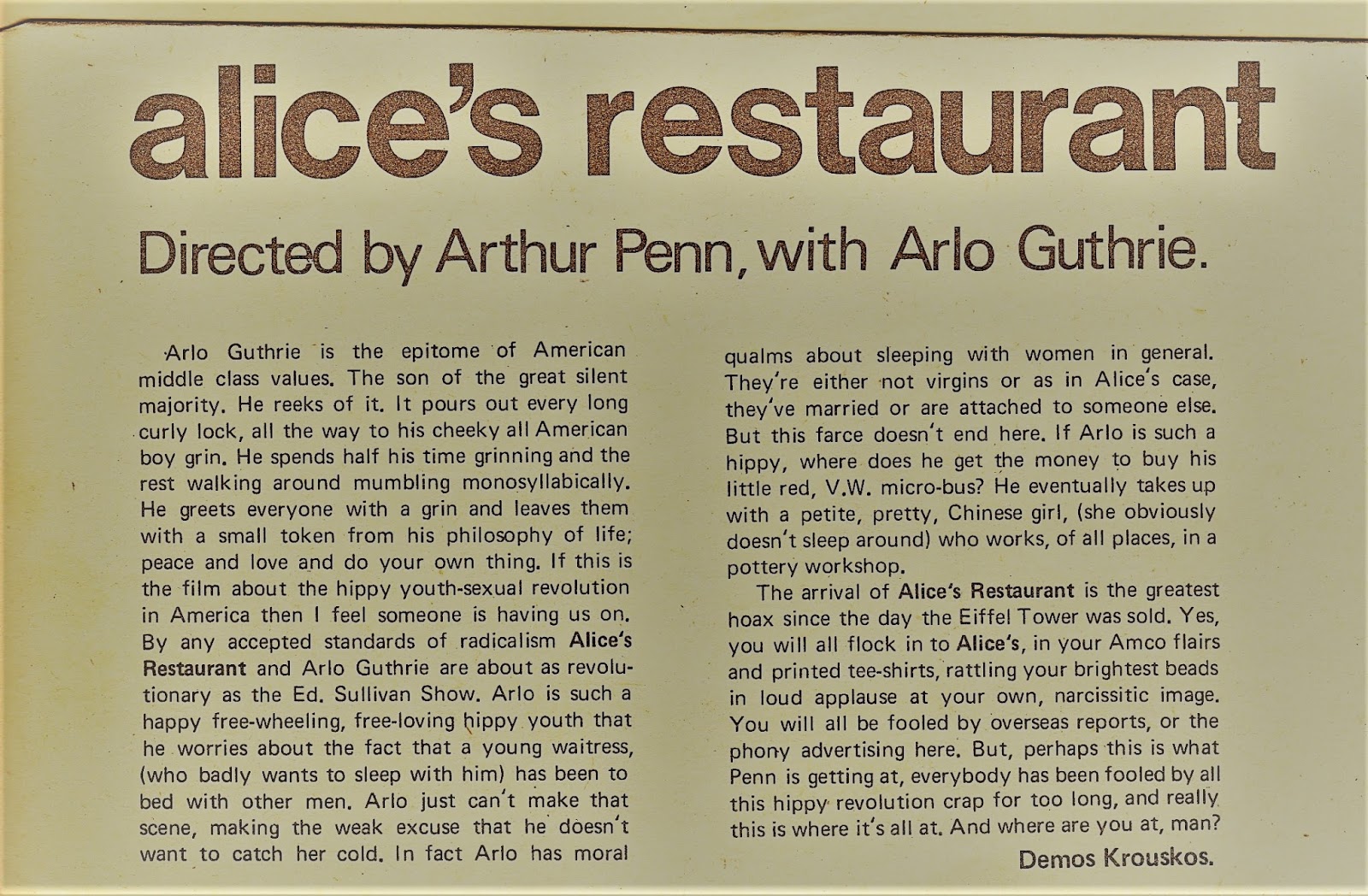

Review by Demos Krouskos

By that stage, I was the only one left in the waiting room and Doc Ferguson emerged saying “What are you doing here?” “I’m next in line,” I replied. “I suppose you’ve got a lot wrong with you as well?” he said. “Yes”, I replied “in fact I’ve got all…” “Just get out of here,” he said. I never heard from the Department of Labour and National Service again, except for one letter informing me my medical history made me unsuitable for the army.

Alice’s Restaurant was not universally liked. In fact, the flippant hippie/yippie humour was despised by some. See the review above from La Trobe student radical and one-time Cinema Papers editor Demos Krouskos in the national student newspaper National U.

Beginnings premiere screening (L-R) Gordon Glenn, Rod Bishop, Scott Murray, (Front) Andrew Pecze

In the months before these shenanigans, with Scott Murray, Andrew Pecze and former student Gordon Glenn we set about making the 50-minute student protest film Beginnings. None of us had made a film before, but Gordon had experience as a camera assistant on Homicide (1964 -1977)and Hunter (1967-1969)at Crawford Productions. Scott’s father John was a filmmaker, helping us with contacts including Phillip Adams who lent us his Steenbeck to edit the film at his advertising agency ‘Moynihan Dayman and Adams’.

We set out to film the aftermath of the first student occupation of La Trobe’s Administration Building, prompted by charges being laid against a handful of students who ran two Defense Department officials off the campus and damaged their Mercedes-Benz. We used Phillip Taylor’s excellent photographs of the occupation and raised the production finance from clubs and societies at La Trobe and NUAUS (the National Union of Australian University Students). Once the charges against the students were dismissed, we decided to follow the principal La Trobe students through the coming July 3rd and July 4th demonstrations in Melbourne’s CBD – Fitzroy Gardens, Bourke Street, Flinders Street Station and St Kilda Road. The film was shot in nine days.

(L-R) Peter Beilby, Keith Robertson, Scott Murray, Gordon Glenn, Rod Bishop

Our great advantage was being known and trusted by all the La Trobe players. Demos Krouskos happily demonstrated how to make a Molotov cocktail, Martin Munz knew exactly how to pitch his two monologues (from one ten-minute take) and the La Trobe demonstrators allowed Gordon into the middle of marches where he shot dynamic footage. Most television stations were content to shoot from the pavements or take high angles from tops of buildings.

Beginnings was an instant success at La Trobe, at universities around the country and at anti-War and peace rallies. It was strident, righteous and in-your-face. The power of the montages of the marches with its combined effect of image, editing and song is remarkable. I’ve not seen anything to equal it since.

We were in a cocoon, however, helped out by everyone from Phillip Adams to the Maoists and the bomb-throwers, but we quickly wised up when the ABC stole the film. Having granted ABC-TV a one-off screening of excerpts for a Cyril Pearl program, we were amazed to see our footage turning up in other ABC programs. Seems Beginnings (or at least our demonstration footage) had been filed with other ABC demonstration footage and nobody in that venerable institution could tell their footage from ours. We quickly learnt about intellectual property and footage sales and the makers of Beginnings have been literally dining out on the proceeds ever since.

1970 Badge

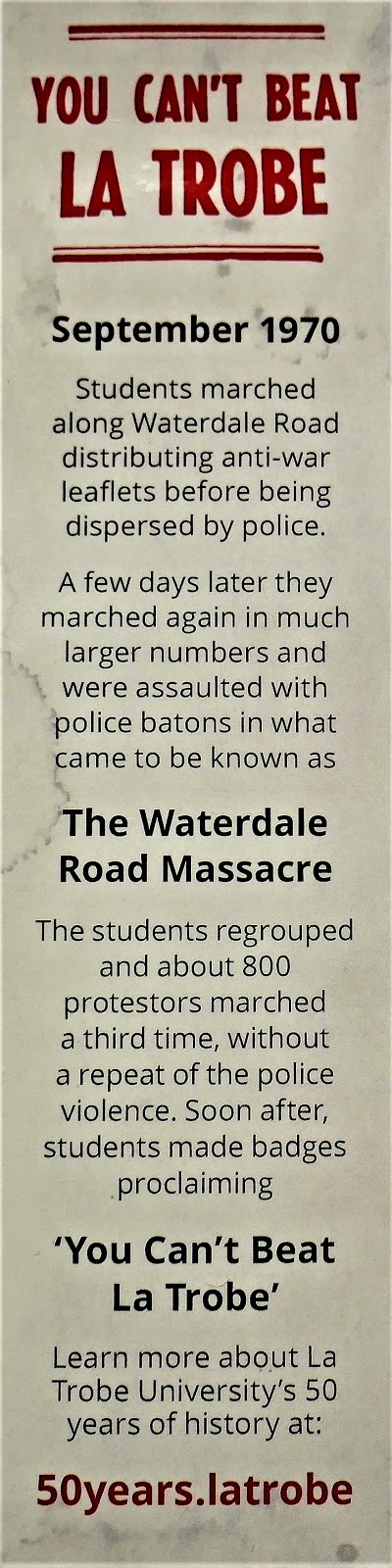

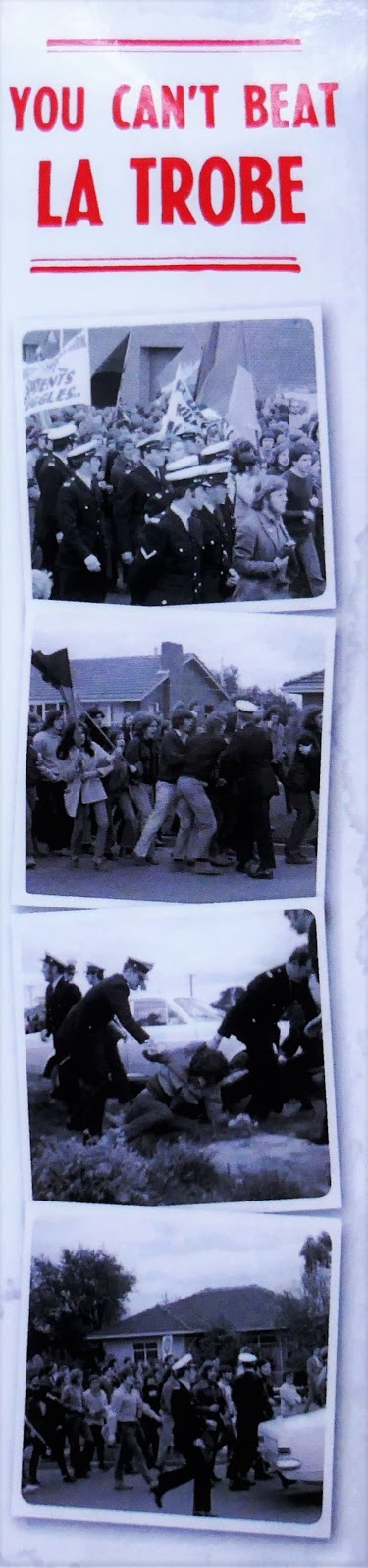

September 1970 and Beginnings premiered at La Trobe; the Department of Labour and National Service targeted me with a summons; and The Waterdale Road Massacres took place. The first occurred on 11th September when 70 students intending to march down Waterdale Road to Ivanhoe to hand out anti-War pamphlets were beaten with batons by police in a clearly pre-mediated ambush. Undaunted, 400 students marched on 16th September, were beaten up again and chased back on to campus. Nineteen students were arrested. Barry York quotes C.D. Starrs, the Post-Graduate representative on the La Trobe University Council at the time, who describes what happened when the marchers were driven back to the campus:

“Students were now scattering farther into the campusÉarmed police leapt out of cars and chased students, bashing any they could; some policemen, unable to catch the students, drew their guns and threatened to shoot. At least one student was arrested at gunpoint. This student was threatened with being shot so that the policeman could make an arrest for the heinous crime of ‘offensive behaviour’.” (pp. 95-96)

Only four months before this, at Kent State University in Ohio, the National Guard fired 67 rounds into an anti-Vietnam demonstration murdering four students and wounding nine, one of whom was permanently paralyzed. How close did we come?

No event politicized the general student body like this one. “In tutorials, I gazed in wonder at students I had known all year, who had never uttered a political remark, let alone anything controversial, who I’d seen among the 800 that turned out to march in defiance down Waterdale Road on 23rd September. These students were now proudly wearing ‘You Can’t Beat La Trobe’ badges. In that final march, perhaps deterred by the adverse press publicity, the massive police presence was benign.

This event in La Trobe’s history may have been almost forgotten, but the organizers of the 50th Year Celebrations produced a great memento of The Waterdale Road Massacre – handed out to all those attending the celebrations on 5 March this year. These events are celebrated in the small printed bookmark published below (back and front).

Bookmark front |

Bookmark back |

References:

Barry York, Student Revolt La Trobe University 1967-1973, Nicholas Press, ACT, Australia, 1989.

This article was first published in Film Alert 101, March 2017

http://filmalert101.blogspot.com/2017/03/my-beginnings-producer-critic-and.html

http://filmalert101.blogspot.com/2017/03/la-trobe-university-turns-50-2-film.html

Thank you to Geoff Gardner and Rod Bishop for permission to republish this article.