Among the many innovative films of the Hollywood Renaissance, Medium Cool is widely remembered for its radical politics and its documentary footage of the calamitous 1968 Democratic Convention and police riots. Yet Medium Cool is also a Hollywood narrative film made by Haskell Wexler, Oscar-winning cinematographer of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (Mike Nichols, 1966), who also, a couple of years prior to Medium Cool, shot the Best Picture of the 39th Academy Awards, In the Heat of the Night (Norman Jewison, 1967). As much as the film chafed against Hollywood convention and critiqued the commercial news media, it also pushed forward a larger Hollywood trend, a revised semi-documentary aesthetic that incorporated cinéma vérité style into Hollywood features like Bullitt (Peter Yates, 1968) and The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971). [1] As much as it spoke to the counterculture, Medium Cool spoke directly to a different audience: Hollywood cinematographers, among whom Haskell Wexler became the most prominent voice for experimentation with documentary equipment and techniques.

In 1967, Haskell Wexler, at the age of 45, was one of the two youngest members of the American Society of Cinematographers (ASC). By point of comparison, Robert Surtees, celebrated for his innovative work on The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967), was 61. The greying of the ASC was largely a result of a protectionist cameraman’s union that fought the threat of runaway productions and closed rank, delaying the acceptance of émigré cinematographers like Lázló Kovács, Vilmos Zsigmond, and Néstor Almendros. [2] The ASC reinforced the professional values and standards of the studio system through American Cinematographer, a publication that served multiple roles as a house organ, a professional journal for filmmakers and a magazine promoting the work of Hollywood cinematographers to the public. For decades the journal directly addressed a readership of amateur filmmakers, but when Herb Lightman, a retired studio cinematographer, assumed the editorship in 1965, he shifted the journal’s focus exclusively to professional filmmaking. [3]

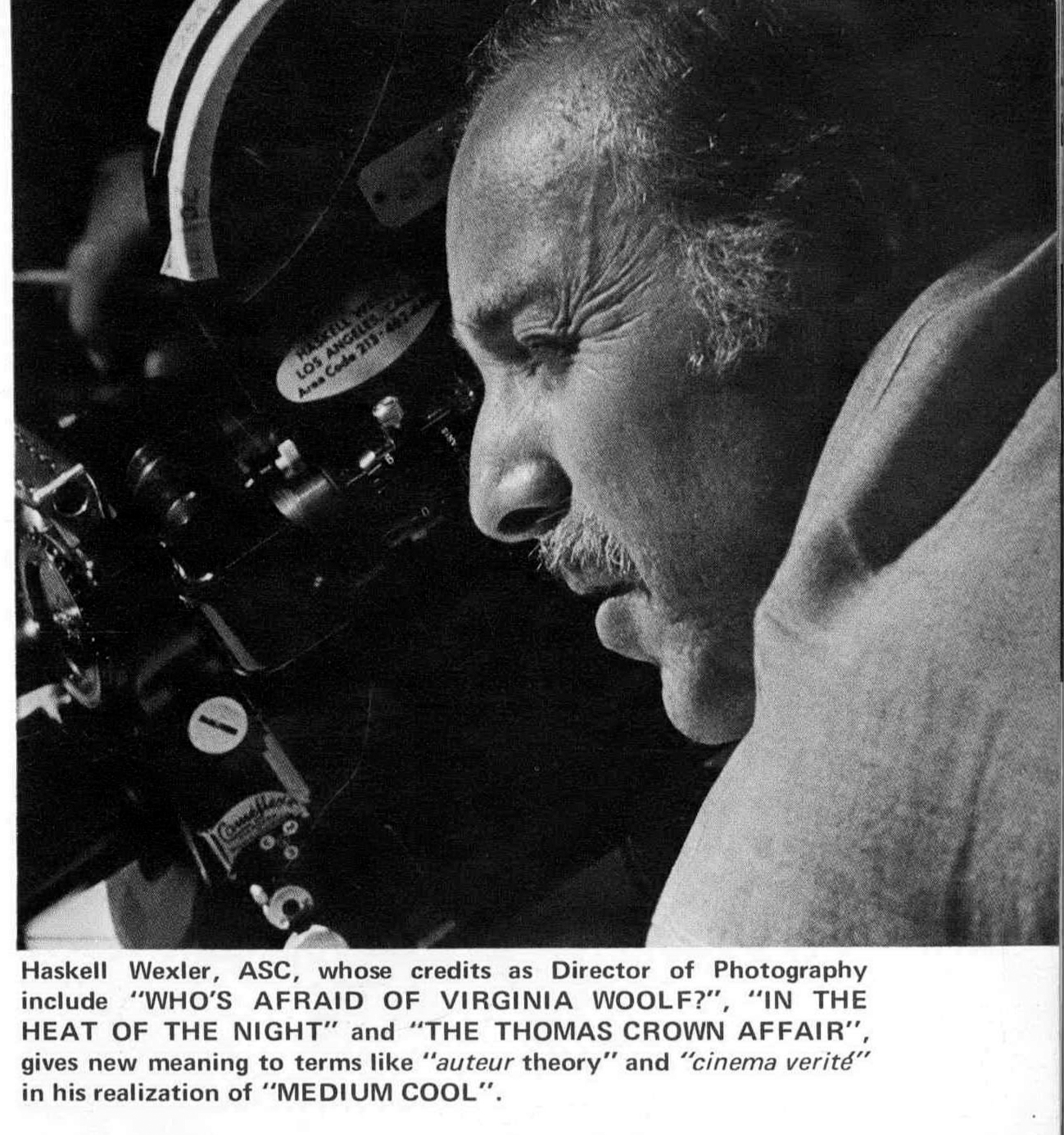

During Lightman’s early tenure as editor, the ASC faced additional threats: New Wave cinema and cinéma vérité. Broadly defined in the US, these descriptives connoted not only handheld camerawork and the use of available light, but, potentially, amateurish cinematography that if widely accepted threatened the aesthetic standards that made well-trained cinematographers essential to Hollywood filmmaking. In both his cinematography and his public discourse, Wexler helped translate the new vérité style into the existing paradigm for narrative cinematography. He became a leading voice for innovation, as well as an exemplar of the appropriate application of new cinematic technologies and techniques. From his Academy Award-winning work on Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf to his work with Norman Jewison on In the Heat of The Night and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) in the late 1960s, he demonstrated how the emergent semi-documentary style of the Hollywood Renaissance might reaffirm rather than challenge the importance of the cinematographer.

Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting provides a valuable paradigm for analysing innovation within classical Hollywood cinematography and, more specifically, the application of documentary techniques to narrative filmmaking. His discussion of William Daniels’s work on Naked City (Jules Dassin, 1948), the landmark post-war semi-documentary, illustrates the “multifunctional” and “modulating” nature of classical Hollywood cinematography. Daniels’ style is multifunctional in the sense that the augmented realism of documentary technique directly serves the narrative, and modulating in his alternation between, for instance, glamour lighting and stark, semi-documentary lighting, depending on the requirements of a given scene. [4] Wexler echoed this approach, distinguishing for instance between the lighting requirements for star actresses Elizabeth Taylor and Faye Dunaway, and naturalistic lighting for action sequences on location. [5]

If Daniels was the consummate insider, Wexler was the consummate outsider, preferring to call himself a documentary cameraman rather than a cinematographer, despite his ongoing, celebrated work on narrative features. [6] And unlike the 1940s, outsiders, whether in the form of European auteurs or upstart Hollywood directors, became the driving force of innovation and threatened the professional authority of the old guard of high studio-era cinematographers. Wexler’s technical prowess and intrepidness on set helped aggrandise the role of the cinematographer. His semi-documentary style tested the limits of existing technology while demonstrating the need for talented professionals, particularly while working on location and collaborating with rising star directors like Mike Nichols and Norman Jewison. Furthermore, as Bradley Schauer demonstrates, cinematographers like Wexler and Gordon Willis gained national publicity for their signature styles and, eventually, opportunities to direct. [7]

Just like Medium Cool, Wexler’s career appears schismatic, not only in his mix of documentary and narrative projects, but also in the apparent disconnect between the hallucinogenic Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the mainstream In the Heat of the Night, and the radical Medium Cool. These films also span (and take part in) the watershed year of 1967, which so frequently divides histories of old Hollywood and the Hollywood Renaissance. The through-line is Wexler’s sustained experimentation in adapting documentary equipment and methods to narrative filmmaking. By analysing Wexler’s work on Medium Cool within – rather than against – the convention of narrative cinematography, we gain a better understanding of how and why a specific style of semi-documentary found acceptance in the late 1960s and continues to shape contemporary cinematography.

In this regard, the camera professionals who read American Cinematographer, which regularly profiled Wexler, were a small but influential audience for his films. While reaching a radical audience with its political content, Medium Cool reached this more conservative audience with its aesthetics. The film opened up a range of possibilities for seasoned directors of photography while asserting their importance to a rapidly emerging style. While the inevitable changing of the guard would bring a new crop of cinematographers to prominence in the 1970s, Wexler helped to bridge this generational divide and to cement the elite status of the ASC in a style that, to the untrained eye, blurred the line between professionalism and amateurism.

Wexler’s Tech

In several interviews with American Cinematographer, Haskell Wexler’s umbrella light was a frequent topic of conversation. [8] By using a reflective umbrella and several small, powerful quartz-iodine lights, Wexler built a compact rig that could flood a room with soft light, akin to natural daylight. By the time he shot Medium Cool, his device had become standard equipment for cinematographers working on location. [9] The origins of this invention are just as important as its adoption by Hollywood, speaking to the role that Wexler played in a changeful era for Hollywood cinematography. Wexler took the idea from still photographers who commonly used umbrella lights. He would adapt other tools designed for photography, documentaries, and commercials to Hollywood features. These fields required small, portable equipment to shoot in everyday locations, ranging from city streets to cramped interiors. And as location shooting became a critical component of the Hollywood Renaissance, in the late 1960s, these technical solutions gained wider application.

Wexler’s work on The Thomas Crown Affair provides a telling illustration of the hybrid approach of old and new Hollywood lighting that characterised the late 1960s. The umbrella light offered ideal soft lights for close-ups of Faye Dunaway. Yet in order to light wide shots of the bank, the site of a spectacular robbery, Wexler needed two arc lights and roughly twenty 10,000-watt lights. Using any more of the massive, hot-burning arcs would have caused too much of a fire hazard. Especially prior to the debut of the faster Eastman 5254 colour stock in 1968 (Wexler used it for a handful of scenes in Medium Cool), documentary technology still had to reckon with the daunting lighting demands of 35mm colour film. [10] But this also set natural limits on the application of new technology that eased adoption by other cinematographers. Rather than overhauling the paradigm for lighting, Wexler demonstrated clear, situational applications for new technologies.

Wexler’s signature tool was his own 35mm Éclair camera, almost exclusively used by documentary filmmakers. Unlike the industry standard Mitchell cameras, the lightweight Éclair facilitated handheld shooting. Hollywood cinematographers occasionally used the similar Arriflex for specific action shots, but prior to Bullitt in 1968, Wexler’s extensive use of a portable camera was exceptional.[11] In fact, even owning a camera was exceptional – Wexler ended up shooting part of John Cassavetes’ Faces (1968) because he could show up with his Éclair on short notice [12] The downside of the Éclair was its noisiness, limiting its application to non-dialogue sequences. Yet, like the umbrella light, it proved effective in specific situations. For instance, the camera allowed for an array of angles and movements during the dance sequence in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, adding a phantasmagorical quality to the debauchery. [13]

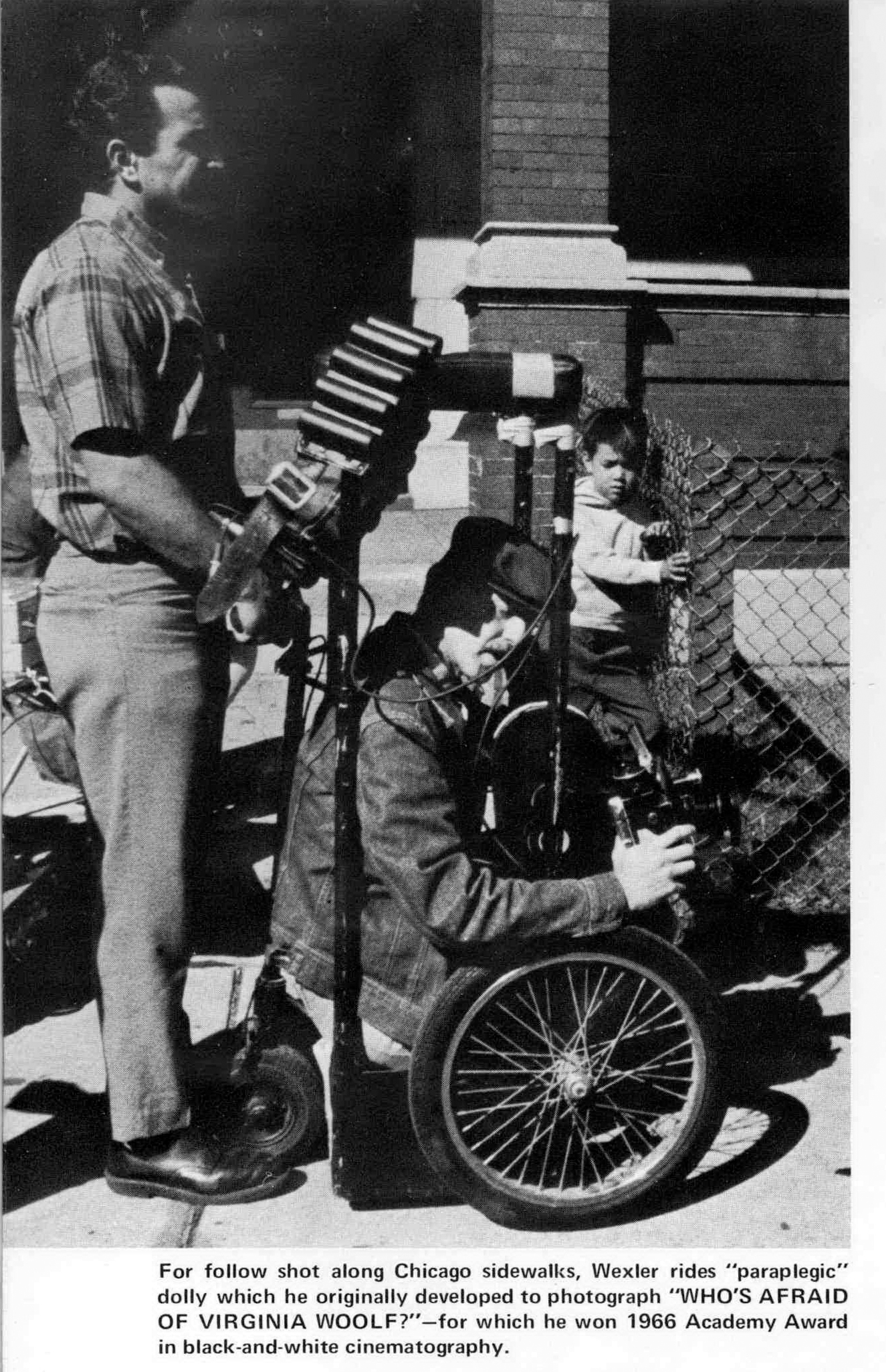

The smaller camera also opened up other possibilities that were economical in both budget and space. The narrow sets for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? were too small to accommodate typical dollies. Instead, Wexler rigged a wheelchair with a camera mount, a technique he developed on his documentary The Bus(1965). [14]

American Cinematographer depicts Wexler using his custom wheelchair dolly on Medium Cool. Herb Lightman, “The Filming of Medium Cool,” American Cinematographer (January 1970): 22–25, 58–59, 75, 80

He would go a step further in The Thomas Crown Affair, mounting the camera to a skateboard for a low moving shot of flares rolling across the floor during the robbery. [15] For Medium Cool, Wexler could mount still photo lenses onto the Éclair, which were faster and less expensive than those available for movie cameras. [16] By eschewing the standard Mitchell camera whenever possible, Wexler was able to take advantage of an array of tools that let him shoot freely with less light and less room to manoeuvre.

A “skateboard” dolly shot further dramatizes the bank robbery in The Thomas Crown Affair. (MGM BluRay, 2012)

Medium Cool became a playground for Wexler’s makeshift technology designed to squeeze out enough light and execute distinctive camera movements. He hung ‘space’ blankets, presumably made from Mylar, to bounce available light akin to his umbrella light. He mounted the umbrella light and plexiglass onto a modified punching bag to capture Robert Forster boxing from the vantage point of the punching bag. Working with the new Eastman 5254 stock, he shot one interior without professional lights, simply replacing an existing lamp with a brighter bulb. For night exteriors, he pushed the new negative in development by over an f-stop, a technique that Owen Roizman would famously employ in his Oscar winning cinematography for The French Connection. [17]

The handheld camera clearly gave Wexler greater access to calamitous events of 1968 as they occurred, allowing him to navigate crowds and narrowly avoid danger during the riots. He found clever ways to work around the noisy Éclair, deploying it often for montages of events woven together by the musical score by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention. In a brief sequence in Washington D.C., he played the dialogue over shots of characters’ boots trudging through mud, eliminating the need for synchronous sound. [18] Finally, using a smaller camera with little additional equipment played a similar function to cinema vérité: it made a number of non-actors featured in Medium Cool less conscious of the camera. In an early sequence, he gathered a group of actual news cameraman and let them talk about their craft, roaming freely with a 16mm camera to capture them documentary-style. [19]

Wexler’s frequent and clever use of new technologies helped ensure his regular appearance in American Cinematographer, whose readers had a clear interest in learning about the potential benefits and drawbacks of new devices before trying them on set. In the case of the Éclair, Wexler even appeared in a testimonial advertisement for the camera. [20] Other upcoming cinematographers like Owen Roizman and Vilmos Zsigmond followed a similar path into American Cinematographer, with articles focused on the pushing and post-flashing of film stock to create the distinctive looks of The French Connection and The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973). [21] Unlike his hybridisation of fiction and documentary, which Hollywood features never truly replicated, Wexler’s technological experimentation in Medium Cool placed him at the centre of the discourse on new technologies in Hollywood cinematography. Years later he was the first cinematographer to use a Steadicam in a Hollywood feature (Bound for Glory, 1976), occasioning yet another prominent appearance in American Cinematographer. [22]

Wexler’s Style

Without the acceptance of members of the ASC, technological innovation had little chance of shifting Hollywood aesthetic norms. Wexler’s overall style faced additional hurdles as it fell under broad descriptions for emergent cinematic styles of the 1960s, principally cinema vérité and new wave. Summarising the frequent condescension towards cinema vérité in the pages of American Cinematographer, one author asked, “Is it sham affectation, this charismatic term – or is it simply another name for a film style that has been around for a long time?” [23] He proceeded to document common vérité techniques as largely distracting, ineffective, or unoriginal. Wexler regularly cited Jean-Luc Godard as his favourite filmmaker, but he wisely never mentioned this in the pages of American Cinematographer in the 1960s, where Wexler’s innovative camera work was held up as an example against the vulgar techniques of the nouvelle vague. [24]

Starting with Virginia Woolf, established professionals celebrated Wexler’s style as innovative but also respectful of the classical values of the cinematographer. As Herb Lightman wrote:

It is to Wexler’s great credit that the hand-held camera is so smoothly employed in Virginia Woolf and so skillfully synchronised to action that it is never obtrusive or distracting. There are none of the self-consciously arty pogo-stick camera convulsions affected by certain misguided nouvelle vague types – to the great annoyance of the viewer. There is no frenetic camera movement for its own sake. In fact, the average viewer would never be aware that a hand-held camera was being used.

Here Lightman pithily rejects this movement as art for art’s sake. For the Hollywood cinematographer, stylistic flourishes that distracted from storytelling were a disservice to the audience. New Wave filmmakers went beyond ‘mannerism’, Keating’s useful term for cinematography that favours one element, such as mood lighting, at the expense of the dictates of the narrative or realist conventions. [25] Rather they veered inconsistently between, for instance, overt stylization and understated realism; or worse, used a realist technique, such as handheld camerawork, so aggressively that it had the opposite effect, alienating the viewer from the perceived reality of the diegesis. By contrast Wexler largely chose unconventional techniques for unconventional scenes, and otherwise largely abided by fundamental rules of Hollywood cinematography. This clearly helped him gain immediate esteem from veteran cinematographers. His Oscar for Virginia Woolf, during an era when the ASC still held sway over the award, provided an opportunity to celebrate creativity without rejecting the artistic achievements of Hollywood veterans. [26]

Rather than crusade against the establishment, as he did politically, Wexler regularly tied his work back to earlier precedents. He shifted f-stops mid-take during Medium Cool, a potentially distracting technique more frequently seen in documentaries. Yet he couched this technique in past precedent, claiming he learned it working for John Seitz, a legend in the field who developed the low-key noir look for Double Indemnity (1944) and other Billy Wilder films. Wexler’s association with documentaries, rather than European art cinema, had an industry precedent. Louis DeRochemont’s semi-documentaries of the 1940s, which American Cinematographer also followed closely, showed that exceptions to conventional lighting, camera movement and composition could be embraced under the rubric of documentary realism. [27] Despite winning an Oscar for a narrative feature, Wexler still liked to refer to himself as a documentary cameraman, an unpretentious technician seeking reality and the best possible image. This went over far better than the overt rule-breaking of the French New Wave.

By the time that he made Medium Cool, Wexler had built up strong enough support from the editors of American Cinematographer that the film’s litany of Godardian violations of the diegesis drew no criticism in a glowing article about the film. [28] Yet there is an important distinction between Medium Cool and Godard’s earliest films, such as Breathless (1960). Wexler remained far less willing than Raoul Coutard to violate tenets of cinematography. His handheld camera work was remarkably fluid, and he rarely tolerated improper exposure within the frame. Rather than making stylistic compromises for challenging locations, such as the cramped interiors of Virginia Woolf and Eileen’s apartment in Medium Cool, Wexler leaned on new technology to naturally light and navigate these spaces.

Wexler uses smooth handheld camerawork and naturalistic lighting in a challenging location: Elaine’s (Verna Bloom) cramped apartment for Medium Cool. (Criterion Collection BluRay, 2013)

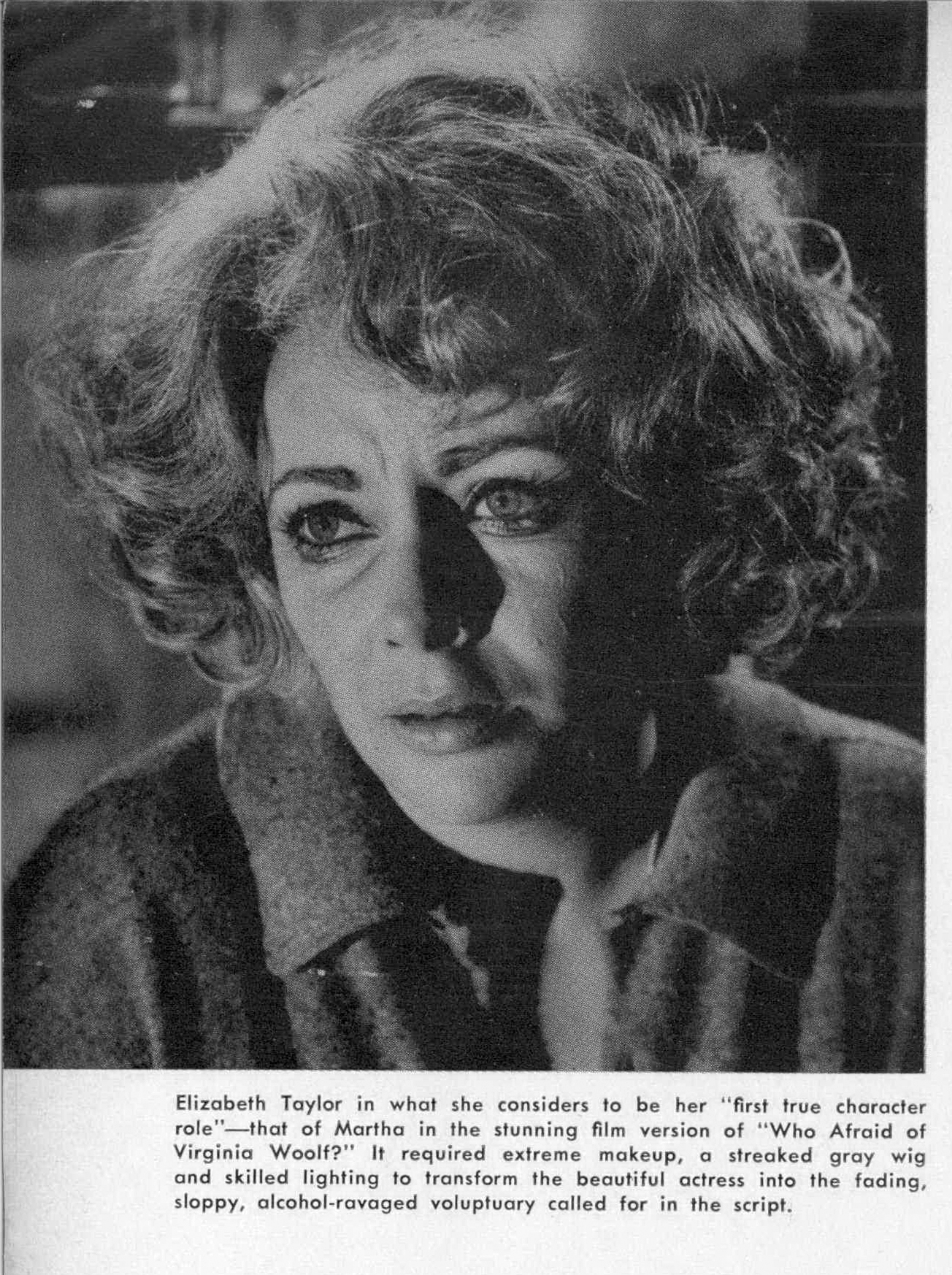

While noting his unconventional tools and techniques, American Cinematographer praised Wexler’s work for its invisibility, a product not only of skilful execution but of its perfect complement to the tone of the scene. Wexler’s unorthodox style fit Virginia Woolf’s drunken and deranged story. Lighting the leading actress was one of the defining strengths of a Hollywood cinematographer, and here it exemplified Wexler’s nuanced application of semi-documentary values. For Virginia Woolf, Wexler replaced Warner Bros. veteran cinematographer, Harry Stradling, whose biggest successes of the early 1960s were the colour musicals Gypsy (Mervyn LeRoy, 1962) and My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964). Nichols balked at Stradling’s glamorous depiction of Elizabeth Taylor in camera tests and tasked Wexler with finding the difficult balance between the fading beauty of the character and Taylor’s innate glamour. As Wexler recounted, Taylor whispered, “don’t do too good a job” ensuring her character was ugly enough on screen. [29] Naturalistic settings and lighting schemes dominated the look of the film, and Taylor appeared “appropriately” unglamorous, but never thoroughly unattractive. Wexler clearly abided by what Keating has defined as the cinematographer’s classical balancing act between competing demands of image quality, story, glamour, and realism. [30]

In the feature image for an article on Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, American Cinematographer emphasizes Wexler’s delicate balance of realism and glamour when lighting Elizabeth Taylor. Herb Lightman, “The Dramatic Photography of ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,’” American Cinematographer (August 1966), 530-533, 558-559.

Wexler perfectly echoed these values in his own statements.

I’m of the opinion that whenever it is possible the camera ought to be mounted on a tripod because in making films, the filmmaker should never call attention to himself or the mechanics of the technique. The purpose of cinematography is to tell the story on film and I only use the handheld camera where I really feel that it will help to do that or where it facilitates shooting of a particular scene. [31]

Paradoxically, while Wexler gained much of his acclaim for his handheld, documentary style, he gained respect from his fellow cinematographers for his appropriate sense of restraint. In the Heat of the Night provides a telling example of how Wexler oscillated between conventional and unconventional techniques. In an early scene a suspect flees a police manhunt towards an oncoming train. The cameraman effectively ran through the woods with the suspect, roughly following the action. Wexler rigged a bicycle wheel to the camera to capture the bloodhound’s view of the chase, a low angle moving shot similar to the “skateboard” shot in The Thomas Crown Affair. [32] In his most audacious shot he uses the full range of the lens to zoom in from an extreme wide shot to a closer shot of the suspect on the railroad bridge.

Yet critically, interior scenes, particularly in the police station, were shot largely on a tripod with conventional lighting and framing. Looking back on the film, Wexler criticised his café scenes, not for a lack of excitement but for imperfect lighting and colour values, which he attributed to his inexperience shooting colour film. [33] In other words, Wexler picked his moments and often picked projects that allowed him to experiment more frequently. In the iconic scene where Detective Tibbs (Poitier) slaps Endicott (Larry Gates), a wealthy white landowner, Wexler perfectly balances indoor and outdoor lighting and the scene plays out in a master shot. The drama was there on screen and the cinematography merely played up the heat, with bright sunlight pouring into the greenhouse.

The groundbreaking “slap” scene from In the Heat of the Night meets conventional Hollywood standards for color, composition and lighting. (MGM DVD, 2008)

Extensive location shooting for The Thomas Crown Affair and Medium Cool provided further justification for new techniques. While there are important exceptions, location work largely connoted aesthetic realism, particularly during the Hollywood Renaissance. Wexler took part in a second wave of semi-documentary style, which, unlike the semi-documentaries of the 1940s, mimicked cinema-vérité techniques rather than wartime newsreels. [34] Balancing actors’ performances with a seemingly detached, observational view of everyday people created a dilemma. Wexler worried that using extras would detract from the realism of the locations – that he’d lose “the little things you capture when you shoot documentaries.” For the bank robbery in Thomas Crown, Wexler used several hidden cameras to effectively capture bystanders unaware while sending actors past the unsuspecting crowd. This technique would be central to the hybrid documentary/narrative style for Medium Cool.

It’s worth noting how far this realist conceit could stretch the boundaries of narrative film towards a documentary style. Wexler shot the bank robbery with four cameras, three of which were equipped with zoom lenses. The long focal length both mimicked documentary form and the distance allowed the camera to be hidden across the street. When the camera couldn’t be concealed, Wexler chose other clandestine run-and-gun tactics. “I simply took the Éclair and stood there on the street corner for about 40 minutes, just holding it under my arm. Then when everything seemed right for shooting the scene, I signalled the actor … I just picked up the camera and shot the scene like a home movie.” [35] Shooting a scene vérité style was one thing; shooting like “a home movie” might appear substandard for a major Hollywood film. Yet ad hoc camera techniques work effectively in The Thomas Crown Affair due to the narrative and production context.

In The Thomas Crown Affair, Wexler uses a hidden camera with a zoom lens, sacrificing pictorial quality in order to capture the immediacy of a bank robbery and to navigate a semi-controlled Boston location. (MGM BluRay, 2012)

A bank robbery progressing in close to real time on an actual location in Boston merits the sense of immediacy brought by the documentary style, enough to justify rougher camerawork. And the precision and audacity of planning and coordinating such a documentary/narrative hybrid for a Hollywood feature justified a departure from the norms as the height of professionalism.

Medium Cool used similar techniques to rather different ends, confusing the boundaries between documentary and fiction rather than imbuing a narrative with semi-documentary realism. Despite the film’s famed reflexivity, the central characters never violate the boundaries of the narrative. They proceed unaware of the camera, in fact bravely unaware in the case of Verna Bloom navigating a police riot without breaking character as Eileen. Wexler noted the strong influence of both The War Game (Peter Watkins, 1966) and The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966) on the film. Both films are semi-documentaries that limn documentary techniques and accommodate moments of stylised cinematography.

Wexler directly borrowed a shot from The War Game with the camera following a motorcycle cop; he went a step further, shooting a motorcyclist driving to deliver news footage and coordinating a handoff of the camera to continue the shot as the rider gets off the bike and walks into the news station. [36] While Wexler decided to cut up this take in the final film, the impulse is telling. There is nothing unobtrusive about the shot – it is yet another camera movement from an off-kilter perspective, much like the bank robbery and polo scenes in Thomas Crown. And like the famed “Look out Haskell, it’s real!” moment, it draws attention to the cameraman, not just as a fly on the wall but as a daredevil. It is active rather than observational. In other words, direct cinema techniques and technology should not be confused with direct cinema ideals in Medium Cool. This semi-documentary style offers such a strong sense of realism and immediacy that ostentatious, dynamic camera movements can pull the viewer closer rather than distracting them. It places Medium Cool in the company of Bullitt and The French Connection where action unfolds like it was filmed by a documentarian with a death wish.

Auteur and Collaborator

While American Cinematographer rejected the pretensions of the New Wave, it reckoned with the new figure this movement helped introduce: the auteur. The journal often signalled its disdain for techniques that drew attention to the director rather than the story. Moreover, the auteur-director threatened to diminish the contributions of the cinematographer. There was a critical line between the accepted role of deferring to a directors’ vision and blindly accepting his demands. In his description of working with directors, Wexler forcefully defined this relationship:

He should try to give the director the shot he wants – but he cannot just be a ‘yes-man.’ If he prostitutes his talents he will begin not to like himself – and if he can’t do that, then nothing else matters. I have worked with other brilliant directors like Elia Kazan and Tony Richardson. These men know what they want, but they are always experimenting. I believe the cinematographer should have the opportunity to experiment also – because if he is ever going to discover more exciting ways to tell the story with film he has to take chances. [37]

In other words the cinematographer had to take a stand, not in defiance of the director but rather to argue for the best way to shoot a scene based on his own artistic talents. The cinematographer had to innovate, finding opportunities to try out new ideas within the framework of narrative features. In this regard The Thomas Crown Affair is radical in a different way than Medium Cool. It’s one thing to experiment on your own production; it’s quite another to use untested techniques on an expensive Hollywood star vehicle. Or to cite Battle of Algiers as a major influence on a crime caper, as Wexler did. [38]

Wexler frequently returned to the theme of experimentation as a way to extend and reinvigorate the role of the cinematographer. At a symposium on the future of Hollywood lighting, Wexler spoke among veteran cinematographers like Arthur Miller, who shot How Green Was My Valley (John Ford, 1941) and Gentleman’s Agreement (Elia Kazan, 1947). As the kid at the table, he framed his use of 16mm cameras as a way to learn new techniques beyond the strictures of major Hollywood productions. He noted:

If something is missing nowadays from our work it’s the opportunity for experimentation … I would like to see some way where we can be ‘active amateurs’ as well as being successful professionals … When the stakes aren’t so high, you’ll try things. And if you try things, you’ll learn, and if you learn, you’ll be a better cameraman. [39]

It was 1967, a year when the naturalistic location shooting of Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) sharply contrasted the massive artifice and expenditure of Camelot (Joshua Logan, 1967), and other roadshow musicals. This was a fraught environment for the aging corps of Hollywood cinematographers. Wexler placed the cinematographer at the forefront of these changes, not as a defender of the old regime but one whose technical ability and creative drive might lead a new aesthetic revival.

Wexler maximised his creative input as a cinematographer in his high-profile collaborations with directors Mike Nichols and Norman Jewison. On Virginia Woolf, Nichols’ status as a first-time director coming from a theatre background elevated Wexler’s contribution as a cinematographer. In American Cinematographer, Wexler was quick to praise Nichols’ command of the frame, but he clearly appeared as the knowledgeable veteran who could translate Nichols’ ideas into dramatic images. Wexler was relatively inexperienced as a Hollywood cinematographer compared to Stradling, whom he replaced on Virginia Woolf, or Nichols’ next collaborator, Robert Surtees. This pairing of a younger cinematographer with a young director seemed to embolden both of them creatively. Nichols trusted Wexler to preserve the grittiness of the story in his cinematography, while Wexler found ways to incorporate his signature handheld camera movements and provocative use of the zoom lens into the film. It’s hard to imagine that such techniques were merely at the behest of Nichols for Wexler clearly drew upon direct cinema practices, a core component of his signature style.

Norman Jewison became an even better partner for Wexler’s experimental proclivities. Unlike Nichols, Jewison was an established professional coming off of a breakout hit, The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming (1966). Whereas Nichols would further establish himself as an auteur director with The Graduate, Jewison’s success relied on talented collaborators to whom he gave wide creative latitude. His work with editor Hal Ashby on The Cincinnati Kid (1965) and The Russians exemplified this approach. The Cincinnati Kid ends with a machine-gun speed montage of a hand of poker, the climax of the film and a precedent for Dede Allen’s famous montage for Bonnie and Clyde. Wexler joined the formidable Ashby and Jewison team for In the Heat of the Night and The Thomas Crown Affair. Thus Jewison had employed not one but two future directors at the peak of their professional careers as editor and cinematographer. Both Ashby and Wexler (albeit for one film, Medium Cool) went on to achieve the auteur status that has eluded Jewison, whose long, successful career serves as a testament to the value of collaboration over singular artistic control.

In a 1968 interview, Wexler voiced his dissatisfaction with the popular liberalism of the “fake sociological script” for In the Heat of the Night, a quote that helped frame the radical politics of Medium Cool as Wexler’s renunciation of his Hollywood work. But Wexler makes this point not to dismiss In the Heat of the Night, but rather to show how his contributions elevated it: “I had met Norman Jewison and knew his heart was in the right place, I liked him, and he encouraged me to contribute what I could to the script.” [40] A cinematographer weighing in on the script? Improbable and maybe apocryphal, but what a strident way for Wexler to frame his transition to auteur while defending his radical bona fides against his commercial oeuvre! Nonetheless, as a creative contributor, Wexler’s cinematography clearly pushed In the Heat of the Night beyond the limitations of its screenplay. The production shot for only three days in Tennessee before the potential danger of racial violence directed at Poitier pushed the remainder of location work to Illinois. [41] But a montage of Wexler’s poignant footage of black cotton workers toiling away as if slavery had never been abolished, serves as a mini-documentary within the film. This trenchant depiction of the South momentarily pulls the viewer away from the dramatic plot, while nonetheless serving a clear narrative purpose: establishing Endicott’s racist milieu and supporting Tibbs suspicion of him. Wexler finds similar asides on location, and Jewison incorporates these unvarnished images of poverty into transitional shots between conventional scenes.

Wexler’s documentary depiction of black Southern poverty appears during transitional scenes for In the Heat of the Night. (MGM DVD, 2008)

Wexler’s documentary depiction of black Southern poverty appears during transitional scenes for In the Heat of the Night. (MGM DVD, 2008)

Despite his political views, Wexler was more than happy to take advantage of creative opportunities for their own sake. Jewison rarely storyboarded, which allowed Wexler to regularly improvise on location. [42] One of Wexler’s favourite anecdotes, recounted in various interviews and commentaries, involves the oncoming train in the opening of In the Heat of the Night. Placing a window screen in front of the camera, the electric lights of the train and platform transform into abstract blurs against the night. He learned this technique from a book called Simple Photo Tricks. [43] This is the perfect encapsulation of his persona, the wily cameraman applying low-budget knowhow to high-end Hollywood productions, and thus straddling vérité and Hollywood filmmaking.

The Thomas Crown Affair was the perfect vehicle for auteurist cinematography because it had no social message. According to Jewison, it barely had enough of a story for a feature film; the script was a mere 80 pages long. Thus Jewison, Wexler and Ashby all conceived the film as primarily a stylistic exercise. Ashby experimented with split screen effects and montage sequences as with the polo scene, which featured exotic camera angles, zooms, and rapid pans by Wexler. [44]

Norman Jewison encouraged creativity and collaboration, allowing editor Hal Ashby to incorporate Wexler’s abstract images into an experimental split-screen montage for the polo scene in The Thomas Crown Affair. (MGM BluRay, 2012).

Jewison effectively trusted Wexler to film dynamic footage and for Ashby to find innovative ways to piece it together. The film has almost a musical structure, loosely connecting the flamboyant cinematography and montage of marquee sequences like the polo game, bank heist, and chess game/sex scene. The utterly apolitical Thomas Crown shoot tested the limits of experimental cinematography within the safety of a breezy commercial caper. Wexler’s location work in Boston served as a test run for the extensive run-and-gun, multi-camera location shooting that he deployed in Chicago for Medium Cool.

With Medium Cool, Wexler provided American Cinematographer with its very own auteur. Herb Lightman floridly compared Wexler to other writer/producer/directors like Orson Welles and Stanley Kubrick, adding that these figures had never photographed their own films. While Medium Cool ostensibly adhered to the dictates of its story, it was conceived as a story that could only be told by Haskell Wexler. By anticipating sites of protest and adapting the story and cinematography to these incidents, Wexler highlighted his ability to blend narrative and documentary camera techniques on location. Bravura handheld shots frequently exceeded narrative demands. The film was Wexler’s most ambitious experiment within the bounds of narrative filmmaking. He shot 16mm footage that he blew up to 35mm. He shot other scenes well below safe light levels for exposure, employing special lenses to reach further into the darkness. Medium Cool displays many of the excesses that drove Hollywood cinematographers to disparage the pretensions of earlier European auteurs. But it was a cinematographers’ film, a loose narrative built for Wexler’s distinctive form of technological and stylistic experimentation. The ASC could forgive a touch of Godard – he was their auteur.

American Cinematographer celebrates Haskell Wexler as “their” auteur. Herb Lightman, “The Filming of Medium Cool,” American Cinematographer (January 1970): 22–25, 58–59, 75, 80.

Medium Cool remains an inimitable blend of narrative and documentary techniques, but perhaps due to its searing portrayal of such a crucial moment in American history, it has a clearer place in documentary history than Hollywood history. Its status as the most radical Hollywood film ever made has severed its intimate ties to the evolving cinematographic style of the Hollywood Renaissance. [45] Medium Cool is an extension, not a rejection of Wexler’s Hollywood corpus. In his most celebrated 1960s narrative features he helped introduce and normalize documentary techniques for Hollywood filmmakers, a new paradigm evident in a range of films from Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969) to Five Easy Pieces (Bob Rafelson, 1970), The French Connection, The Getaway (Sam Peckinpah, 1972), and The Long Goodbye. Younger cinematographers like Owen Roizman, Lázló Kovács, and William Fraker came to define the semi-documentary style of the 1970s, arguably more so than Wexler himself. But Wexler’s early articulation of the new style within the existing paradigm of American cinematography opened the path that Hollywood ultimately took, one of greater aesthetic experimentation under the aegis of semi-documentary realism. Medium Cool tested how far Hollywood features could stretch to incorporate documentary techniques, influencing both the old and the new generation of cinematographers. In the end, Hollywood dismissed Medium Cool’s substance but absorbed its style.

Notes

[1] The semi-documentary look of the 1960s and 1970s is detailed in Paul Ramaeker, “Realism, Revisionism and Visual Style: The French Connection and the New Hollywood Policier“, New Review of Film and Television Studies, Vol. 8, No 2 (June 2010), 144-163; see also Joshua Gleich, Hollywood in San Francisco: Location Shooting and the Aesthetics of Urban Decline, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018, 199-204; Nathan Holmes, Welcome to Fear City: Crime Film, Crisis, and the Urban Imaginary, Albany: SUNY Press, 2018, 99-100.

[2] Gleich, 190; 312n49.

[3] Robert Birchard, “Shaping Cinematography’s ‘Magazine of Record'”, American Cinematographer (August 2004), https://theasc.com/magazine/aug04/record/page1.html (last accessed June 12, 2020).

[4] Patrick Keating, Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 248-250.

[5] Herb Lightman, “The Dramatic Photography of ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,'” American Cinematographer (August 1966), 530-533, 558-559; Herb Lightman, “The Filming of Medium Cool,” American Cinematographer (January 1970): 22-25, 58-59, 75, 80.

[6] “Motion Picture Lighting,” American Cinematographer (July 1967): 480-483, 500-501, 510, 512-513.

[7] Bradley Schauer, “The Auteur Renaissance, 1968- 1980,” in Patrick Keating, Ed., Cinematography, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers U. Press, 2014, 101.

[8] “Motion Picture Lighting;” Lightman, “The Dramatic Photography;” “The Boston Location Filming of ‘The Thomas Crown Affair,'” American Cinematographer (October 1968): 740-743, 786-787, 793-795.

[9] Lightman, “Medium Cool.”

[10] “The Boston Location Filming.”

[11] Gleich, 177-178.

[12] Haskell Wexler Oral History, 269, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Beverly Hills, CA.

[13] Haskell Wexler DVD Commentary, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?; (Warner Home Video, 1997).

[14] Lightman, “The Dramatic Photography.”

[15] Haskell Wexler and Norman Jewison, DVD Commentary, The Thomas Crown Affair (MGM, 2012).

[16] Lightman, “The Filming of Medium Cool.”

[17] “Photographing The French Connection,” American Cinematographer (February 1972): 1028-1031, 1067-1069.

[18] Haskell Wexler DVD commentary. Medium Cool (The Criterion Collection, 2013).

[19] Lightman, “The Filming of Medium Cool.”

[20] Éclair Ad, American Cinematographer, February 1969.

[21] “Photographing The French Connection;” Edward Lipnick, “Creative Post-Flashing Technique for ‘The Long Goodbye,'” American Cinematographer, March 1973, 278-81, 334-35, 328-29.

[22] “The First Feature Use of Steadicam-35 on ‘Bound for Glory,'” American Cinematographer, July, 1976, 788-791, 778-779.

[23] Edmund Bert Gerard, “The Truth About Cinema Verite,” American Cinematographer, May 1969, 474, 502.

[24] Haskell Wexler DVD Commentary, Medium Cool.

[25] Keating, 190-192.

[2] Mark Harris, Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood (New York: Penguin, 2009), 389-390. Harris notes the omission of In the Heat of the Night from consideration for Best Cinematography as a way of elevating more traditional cinematography. Judging from Wexler’s high esteem among his peers, it more likely had to do with Wexler’s inexperience with colour film.

[27] Gleich, 3-4.

[28] “Motion Picture Lighting.”

[29] Ernest Callenbach, “The Danger is Seduction: An Interview with Haskell Wexler,” Film Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 3, Spring, 1968, 3-14.

[30] Keating, 3-7.

[31] Lightman, “The Dramatic Photography.”

[32] Haskell Wexler and Norman Jewison DVD Commentary, In the Heat of the Night (MGM, 2008).

[33] Wexler and Jewison DVD Commentary, In the Heat of the Night.

[34] Gleich, 199-204; Holmes, 99-100.

[35] “The Boston Location Filming.”

[36] Wexler DVD Commentary, Medium Cool.

[37] Lightman, “The Dramatic Photography.”

[38] “The Boston Location Filming.”

[39] “Motion Picture Lighting.”

[40] Callenbach, “The Danger is Seduction.”

[41] Wexler and Jewison DVD Commentary, In the Heat of the Night.

[42] Wexler and Jewison DVD Commentary, The Thomas Crown Affair.

[43] Wexler and Jewison DVD Commentary, In the Heat of the Night; Wexler Oral History, 238.

[44] Wexler and Jewison DVD Commentary, The Thomas Crown Affair.

[45] Piper French, “High Visibility: Reexamining Medium Cool on Its 50th Anniversary,” Los Angeles Review of Books, Aug. 23, 2019, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/high-visibility-reexamining-medium-cool-50th-anniversary/ (last accessed June 12, 2020).