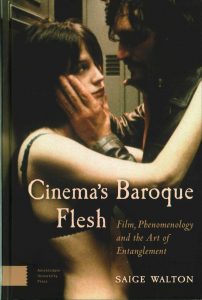

| Saige Walton Cinema’s Baroque Flesh: Film, Phenomenology and the Art of Entanglement Amsterdam University Press, 2016 ISBN: 9789089649515 Au$149.76 (hb) 278pp (Review copy supplied by Amsterdam University Press) |

|

In Cinema’s Baroque Flesh, Saige Walton presents a rich and deeply engaging media archaeology that finds a “strong sensorial continuity” (22) between the historical baroque’s painting, sculpture, prose, illustration, architecture and collecting traditions such as cabinets of curiosity, and twentieth and twenty-first century baroque cinema. Through a phenomenological analysis, Walton finds that baroque art and film alike forge “spatial, emotive, and sensuous connections between bodies” (12). This notion of sensuous entanglement is the book’s primary point of inquiry, and it is mapped out across an analysis of the reversible, reciprocal “flesh” of the material world.

Walton is careful to delineate her definition of cinematic “flesh”. It does not anthropomorphise film; film clearly does not have a body in the same way that humans do. Rather, the film body can perceive and express in ways that are analogous but not identical to the lived body. Walton takes her cue from mid-twentieth century phenomenological philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s theorisation of the “flesh” of the world, which refers to the fundamental reversibility, reciprocity and entanglement between embodied beings. She writes of the cinema and the spectator: “[f]ilmmaker, film, and spectator alike can all be considered as viewers viewing, dynamically engaged in the perception of expression (the visual) and the expression of perception (the visible)” (47). While “the film’s body is substantially different to ours we are adverbially simpatico. As with our own embodied existence in the world, film is a viewing, sensing, and experiencing subject as well as being visible and sensible for others” (50).

This “flesh” is particularly charged with “sensuous, spatial, and emotive implications” in baroque cinema (46), because “embodied vision, movement, and materiality” are so intrinsic to these films (22). The cinematic baroque is always proximate, inviting the spectator into a dynamic and sensuous entanglement with the film. Richly textured, sensuous surfaces, reversing the positions of viewer and viewed through perceptual instability (63), and the theatrical self-referentiality of frontal address that draws the spectator into the fantasy space of the film, all activate this sense of intimacy and intertwining of film bodies and spectatorial bodies.

Some of Walton’s choices of film texts to illustrate this art of entanglement are surprising and unexpected – Michael Haneke’s visually austere Caché (2005) and the silent comedies of Buster Keaton, for instance – because she extends the theorisation of the cinematic baroque beyond films that boast extravagant visual spectacle. She cautions that, while these are the types of films that often come to mind when we think about the baroque,

[d]elimiting the baroque to the visual is at odds with many of the experiences of baroque flesh […] its knotting of sensation, its stirring of the passions, its coextensive space, or its attraction to material textures, skin, and the surface. Any conception of baroque cinema needs to consider the longstanding sensuality of this aesthetic and its art of entanglement. Baroque flesh always engages our embodied perception, no matter how “maddening” its vision might become (186).

The reader is invited to consider the sensuous, embodied and emotional aspect of film and how “a film can feel baroque” (21). The theorisation of cinematic “flesh” restores attention to the baroque’s sensuous aesthetics and allows for an exploration of baroque tickles, shocks, throbs and bites throughout the book’s analysis of a wide range of film genres, national cinemas and points in film history.

Throughout this analysis of the sensuous, however, Walton does not confine her attention to the pre-reflective body, but rather attends to the dual significance of cinema’s “embodied intelligence as well as the passionate density of our feeling flesh” (105). One of the book’s exciting and productive propositions is that we can reframe phenomenological studies of film beyond binarisms that place semiotics and the sensuous, language and experience, and image and story in diametric opposition to each other. Cinema’s Baroque Flesh demonstrates that this need not be the case; instead, we can consider them in a correlative relationship with one another – what Walton calls “an inherently renewable exchange that is akin to the chiasmatic structure of the ‘flesh’” (133). The film analyses are committed to this flexible approach and produce readings that revitalise scholarly approaches to both the body and intelligence of cinematic “flesh”.

Walton’s passion and enthusiasm for her chosen film texts is contagious. She conducts highly original close analyses of the films, which she dubs “dynamic thought experiments in what a baroque cinema of the senses might involve and how it is experienced” (26). I find Walton’s close reading of Claire Denis’ cult classic Trouble Every Day (2001) most compelling in this regard, as she so vividly observes the film’s multiple ruptures of borders that evoke tearing, biting, and crushing sensations. She writes, “I find that this film gets ‘on the inside’ of me and I get ‘on the inside’ of it through a baroque breaching of borders, frames and surfaces” (114), a beautiful description of the deeply carnal and passionate experience of the cinema. As film theory continues to turn more and more to the question of how the film body and the spectatorial body interact and intertwine, Cinema’s Baroque Flesh proves an invaluable contribution. By theorising the flesh of baroque cinema as both thoughtful and sensuous, Walton prompts us to look at and experience it anew.