Click here to view Knocknagow (1918)

In January 1920, an Irish-made film received the following tribute from a leading Dublin newspaper:

It is common talk among exhibitors in Ireland that no picture was ever shown in the country that secured anything like the enthusiastic support given to Knocknagow. It is probably the only picture that is given repeats in nearly every village and town in Ireland, in the same picture house, in many instances four and five times, and many picture houses are now under contract with the company for the annual presentation of Knocknagow to their patrons. (Freeman’s Journal, 28 January 1920, 5)

Knocknagow, a historical drama set during the land-clearances of the 1840s, had been produced by James Mark Sullivan, a prominent Irish-American lawyer, and directed by Abbey Theatre actor-manager Fred O’Donovan. Its production company, The Film Company of Ireland, was one of Ireland’s first.[1] Far from being a fresh release, however, Knocknagow had been shown repeatedly to Irish audiences since its premiere in January 1918. That a film more than two years old continued to fill cinemas and village halls, perhaps on dates of national significance, signals the unique status that it had acquired in a country now on the eve of independence. Its screening, noted the Freeman’s Journal, “is becoming an event, much like the constant presentation of The Lily of Killarney in opera” (28 September 1920, 5).[2] Knocknagow, while not the first Irish-made feature, thus has an important place in the history of film in Ireland. More than just “Ireland’s first big production” (Irish Limelight, July 1918, 8), it was Irish cinema’s first national and international success.

The Irish Film Company

The Film Company of Ireland (henceforth FCOI) had a short but eventful existence. Founded in March 1916 by Sullivan and Henry M. Fitzgibbon, it endured the destruction of its Dublin premises during the 1916 Easter Rising, the internment of one of its founders in May 1916, and bankruptcy proceedings in June 1917 (Slide, 12). By September 1920, the company had been forced to suspend production—“the Film Company of Ireland is being reconstructed and, when equipped with an up-to-date studio, will immediately commence picture production on an extensive scale,” noted the Freeman’s Journal (9 September 1920, 6)—and when British soldiers came to ransack its offices in December that year, they found them empty.[3] At this point, the FCOI’s operations in Ireland all but disappear from view. Why the company foundered is unknown. Perhaps it was simply unable to raise further capital amid the political and economic turmoil caused by the escalating war between British forces and the Irish Republican Army.

Of the numerous fiction films shot on location in Ireland before 1916, almost all were produced by American or British companies. In 1908, footage of Ireland appeared in two comedies produced by Arthur Melbourne-Cooper for the Charles Urban Company as well as a short drama made in Galway by another British film pioneer, Robert W. Paul (Slide, 4). Pioneering efforts by native Irish film-makers included the Photo-Historic Film Company’s three-reeler biopic The Life of St. Patrick (1913, dir. J. Theobold Walsh), Irish Film Production’s one-reeler Michael Dwyer (1913) and Love in a Fix (1913), and an amateur short titled Fun at Finglas Fair (Ireland 1915) (Slide, 11; Condon, 237–8). Early silent films made by American companies included two short comedies directed by Larry Trimble for the Vitagraph Company, Michael McShane, Matchmaker (1912) and The Blarney Stone (1913), and a political feature titled Ireland a Nation (1914, dir. Walter Macnamara) (Slide, 43–4). But it was the Kalem Company of New York which revealed Ireland’s true commercial potential as a site of film production.[4] Working from a studio near Killarney, County Kerry, the company filmed a succession of popular dramas—notably Rory O’More (1911), The O’Neill (1912), and Ireland the Oppressed (1912)—and adaptations of plays by Irish playwright Dion Boucicault, including The Colleen Bawn (1911), Arrah-na-Pogue (1911), and The Shaughraun (1912). All were directed by Sidney Olcott, who also returned to Ireland with his own company to make For Ireland’s Sake (1914), Come Back to Erin (1914), The Irish in America (1915), and Bold Emmett, Ireland’s Martyr (1915).

The FCOI worked quickly to meet the evident demand for Irish films. By the end of 1916, it had released nine titles, mostly one-reel comedies: O’Neil of the Glen; A Puck Fair Romance; Woman’s Wit; Widow Malone; The Miser’s Gift; Food of Love; An Unfair Love Affair; The Eleventh Hour; and The Girl from the Golden Vale (see Appendix F). During its second year, the company expanded its range with Serial of Twenty Irish Scenics and a clutch of multi-reel dramas: A Girl of Glenbeigh; Cleansing Fires; A Man’s Redemption; Rafferty’s Rise; When Love Came to Gavin Burke; and, most importantly, Knocknagow. “The Irish Company,” as it was known to the general public, had by now gathered a core of talented actors and crew, including several luminaries of Dublin’s Abbey Theatre: actor-directors J. M. Kerrigan and Fred O’Donovan; cinematographer William Moser; and “star” actors Brian Magowan (also spelled MacGowan) and Nora Clancy, whose verisimilar performance styles were particularly well suited to the medium of film (Condon, 116). One observer predicted that the company, once installed in a new Dublin studio with “the most up-to-date lighting system known”, would “give considerable employment” and “encourag[e] an Irish school of film acting” (Evening Telegraph, 13 December 1919, 4). Nevertheless, a long hiatus in production seems to have occurred in 1918, and in the following year the company produced only one “Super-film”, Willy Reilly and His Colleen Bawn (1920, dir. John MacDonagh), and a two-reel comedy titled Paying the Rent (dir. John MacDonagh). Willy Reilly and His Colleen Bawn also proved a hit in Ireland and the United States, and while details of the reception of Paying the Rent (of which a single reel survives) are lacking, the fact that it was shown in two different Dublin cinemas for a week in December 1921 suggests that it, like other FCOI productions, enjoyed a reasonably long circulation (Rockett 1988, 30).

Knocknagow

By May 1917, work on Knocknagow was reported to be “under way” (Irish Limelight, May 1917, 6). During June and July, the company’s cast and crew stayed at Hearne’s Hotel in Clonmel (fig. 1) while shooting scenes around Tipperary’s Golden Vale and at an unidentified “old mansion near Clonmel” used to represent the home of a prosperous family of tenant farmers (fig. 2) .[5] The nearby mountain of Slievenamon, a well-known landmark, provided the dramatic backdrop for the film’s long opening panorama (fig. 3) , apparently taken from a vantage point to the south-east of Clonmel, while the town itself is identified in several of the film’s intertitles, including a sequence that depicts the hero languishing in its jail at Christmas. Immortalized by an eighteenth-century poem, “The Convict of Clonmel,” Clonmel Gaol had strongly patriotic associations as a place of incarceration for Irish revolutionaries, and images of it could well have been among the many shots of Clonmel which, as a local newspaper noted regretfully, ended up on the cutting-room floor (Nationalist, 6 February 1918, 6). Irish audiences would certainly have recognized the town’s Westgate in the scene in which Billy Heffernan encounters the English dragoon (fig. 4) .

Knocknagow was a screen adaptation of a novel whose popularity in Ireland during the nineteenth century has been described as second only to the Bible. Its author, Charles J. Kickham (1828–1882), was synonymous with Tipperary. A veteran of its abortive Young Irelander Rebellion in July 1848, he wrote numerous sketches of local life, popular poems such as “Slievenamon” (1857), and three novels: Sally Cavanagh; or, The Untenanted Graves: A Tale of Tipperary (1869); Knocknagow; or the Homes of Tipperary (1873; part-serialization 1870); and For the Old Land; or, A Tale of Twenty Years Ago (1886).[6] Descriptions of Tipperary customs, folklore, dialect, and landscape make up a large part of Kickham’s Knocknagow; or the Homes of Tipperary. It was thus as much to highlight a selling-point as to acknowledge the impossibility of filming anywhere other than in Tipperary that the FCOI announced in full-page advertisements on the back covers of the Irish Limelight for May and June 1917: “The Production will embrace the very valleys and mountains where Kickham laid his famous story.”

The issue of authenticity was clearly of paramount concern for the film’s producers. Most of the novel’s action takes place in the fictional hamlet of Knocknagow and its neighbouring village of Kilthubber, which Kickham modelled on Mullinahone, the village where he grew up, some twenty miles from Clonmel.[7] And minute examination of individual frames from Knocknagow shows that the FCOI shot all of the film’s Kilthubber scenes in Mullinahone, despite its inconvenient location on the far side of Slievenamon from Clonmel (see fig. 5 , fig. 6 , and fig. 7 ). Curiously, however, the fact that much of Knocknagow had been filmed in Kickham’s own village was nowhere mentioned in the advance notices or reviews in the Irish press, not even in local Tipperary newspapers which would presumably have been keenly interested in such details. By contrast, as Gary D. Rhodes notes in his contribution to this issue, the publicity materials given to the Irish-American press in Boston highlighted the film’s use of Mullinahone as a location, describing the emptying of the village for an afternoon and the presence of thousands of curious onlookers.

By November, post-production of Knocknagow was sufficiently advanced for the FCOI to invite bookings from cinema-owners and film exhibitors (Irish Independent, 10 November 1917, 2). The film premiered at Magner’s Cinema in Clonmel on 30 January 1918, where it ran for four nights. As Denis Condon has established, it was then screened at a succession of venues around Ireland, including Cavan (26–28 February), Cork (18–23 March), Waterford (1–3 April) , Derry (8–13 April), Limerick (15–17 April), Belfast (15 April), and Galway (22–24 April). In Dublin, it was screened to the trade on 6 February 1918, opening to the public on 22 April at the Empire Theatre, where it ran until 26 April or later, under the billing “A Photo-Play of Unique National Interest” (Irish Limelight, April 1918). Details of Knocknagow’s progress thereafter are scarce, but contemporary newspaper advertisements refer to further screenings in Dublin (13–15 May 1918 [Phibsboro’ Picture House]), Navan (5–6 August 1918), Nenagh (1–3 September 1918), Dublin again (15–17 July [Theatre de Luxe], mid-August 1918 [Tivoli], and 26 October 1918 [Cosmo Bazaar]), Dundalk (25–27 November 1918), Naas (late February 1919), Roscrea (27 September 1919), Castlebar (23 November 1919), and Cavan (27–28 December 1919).[8]

In the United States, as Rhodes has discovered, Knocknagow began a three-week run at Boston’s Tremont Temple on 9 December 1918, with further confirmed showings in Yorkville (New York) (4–?? December 1920); New York City (16–?? April and 25 September–7 October 1921, and 17 March 1928); Pittsburgh (April 1928); Baltimore (November 1928); and many others.[9] Maryanne Felter and Daniel Schultz’s researches into the Wharton Releasing Corporation Records at Cornell University Library indicate that Knocknagow was also screened at Catholic schools and organizations, Irish-American groups, and cinemas in New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Illinois, and even Canada (Felter and Schultz 2004, 35). In Britain, Knocknagow went on general release in May 1918, was reviewed by the Bioscope on 16 October 1919, and appeared on a “Great Irish Film Week” programme (5–10 January 1920) at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall, one of the largest venues in the country, before beginning a tour of England and Scotland (Bioscope, 16 October 1919, 58; Watchword of Labour, 27 December 1919; Freeman’s Journal, 28 January 1920, 5; Manchester Guardian, 5 January 1920, 8).

Knocknagow did well in all three countries. The Irish Limelight described its opening run in Dublin as “extraordinarily successful” (April 1918, 11), a verdict echoed two years later by the Freeman’s Journal when it pronounced the film a “huge success” (28 January 1920, 5). Indeed, the film’s extended tour of the Irish provinces, including repeated showings in small towns and villages where moving pictures were a relatively novel and irregular diversion, must be seen as an index of its commercial strength and longevity. As the Meath Chronicle noted: “[T]he treat is one seldom afforded to patrons of the pictures in provincial towns, and one there is little doubt will be much appreciated” (27 July 1918, 5). In Britain, the trade journal Bioscope conceded grudgingly that Knocknagow had done “big business” in Manchester (15 January 1920, 108), where it had been advertised as “The Film that made such success in Ireland & America” (Manchester Guardian, 5 January 1920, 8). In Boston, where it was claimed (perhaps fancifully) to have taken “more money than the much ‘boosted’ ‘Birth of a Nation’” (Evening Telegraph [Dublin], 13 December 1919, 4), Knocknagow was introduced by David Walsh, the Democratic Senator for Massachusetts, who was loudly applauded for declaring that “this film play . . . has started a movement to place the story of Ireland and her sufferings before the world for an unbiased verdict” (Boston Daily Globe, 10 December 1918, 3).[10]

Distribution was aided by canny marketing on the part of Knocknagow’s producers. A full-page advertisement in the Irish Limelight reproduced a telegram, purportedly from the manager of Magner’s Cinema in Clonmel, describing how “Waiting crowds necessitated police supervision” (February 1918). Newspaper advertisements recycled the company’s claims that production costs had exceeded £9,000, and referred to the film by an array of epithets (“Super-Film,” “Super-Production,” “The Great Irish Super-Production,” “Ireland’s Great Super Film”) evidently intended to repackage it as an Irish reply to D. W. Griffith’s epochal “super-film” Birth of a Nation (USA 1915).[11] The FCOI also took pains to co-ordinate with cinema owners and exhibitors. Indeed, despite being formulated as an expression of gratitude, the FCOI’s notice in the Irish Limelight that “Irish Exhibitors are meeting the Company more than half way” (July 1917, emphasis added) may even indicate that it was in a position to impose special conditions on exhibitors keen to acquire its popular titles.

The FCOI had used innovative methods to attract audiences as early as July 1916, when its cameraman had filmed patrons of O’Neil of the Glen at Dublin’s Bohemian Theatre before appending the footage to the next day’s main feature in hopes of luring them back for a second viewing (Slide, 12). At this time, Irish exhibitors were keen to give native productions special fanfare through what would today be called promotional screenings and multimedia tie-ins. By making the screening of Irish films into events, filmmakers and cinema owners joined forces in a celebration of Irish cultural autonomy and industrial achievement—“A Triumph for Irish Industry and Enterprise,” as Waterford’s Evening Star described Knocknagow on 1 April 1918—while staking their claim to arguably the most effective medium for telling stories and disseminating propaganda.[12] As a “Super-Production” able to generate headlines such as “Ireland’s Own Film” (Irish Limelight, July 1918), Knocknagow offered a unique opportunity which the FCOI seized with both hands by arranging for two of the film’s stars, Brian Magowan, “one of the Leading Baritone-Tenors of Ireland” (Evening Star, 1 April 1918), and Breffni O’Rourke, to accompany screenings with recitations of Irish songs and “witty stories” (Anglo-Celt, 2 March 1918, 14). (On other occasions, the film was supported by local singers and musicians.)

As Condon notes, although such appearances were not unprecedented, particularly when screenings formed part of a variety programme, the “singular kind of intermediality” represented by Magowan in character as “Mat the Thrasher” at showings of Knocknagow sat awkwardly with the illusionist aesthetic of contemporary Hollywood productions (Condon, 117). Even so, it is testimony to the depth of audiences’ desire to connect with the fictional universe that the film had brought to life, and, as such, bears comparison with W. J. Walshe’s popular stage dramatization, also titled Knock-na-gow; or, The Homes of Tipperary, which played at venues around Ireland both before and after the FCOI’s film version.[13]

In Ireland, the critical reception of Knocknagow was predictably enthusiastic. Reviewers echoed the Irish Limelight’s claim that the film was “the greatest attraction ever offered to Ireland’s cinema-loving public” (Irish Limelight, February 1918, 8), and suggested that its real audience lay among the Irish diaspora: “The film should make a special appeal to the exiled Irish in England as well as in America and Australia” (Clonmel Chronicle, 2 February 1918, 5); “it is in America that [the FCOI’s] greatest triumph shall lie” (Anglo-Celt [Cavan], 2 March 1918, 14). British reviewers were more critical but generally positive. Britain’s Bioscope, while critical of the film’s propagandistic elements and “many technical faults”, praised the quality of acting and recommended thorough re-editing in the interests of narrative clarity. “Seldom have so many perfect men and women been gathered together into one case,” approved the Kinematograph Weekly for its part: “The men look like men and not the doll-like creatures we are used to seeing in heroic parts” (qtd. in Watchword of Labour, 27 December 1919, emphasis in original). In the United States, critical opinion ranged from hyperbole by Irish-American newspapers (“The best photography we have seen in any European picture to date” [Boston Globe qtd. in Slide, 14]) to Variety’s brutally unsympathetic verdict: “It’s just ‘play-acting,’ all the way, with no illusion to make the spectator believe he is witnessing anything more than a company of actors, impersonating human beings” (30 September 1921, 35).

From page to screen

In 1917, Condon notes, the FCOI was “under pressure to produce a landmark production that would seal its status as Ireland’s film company, a national epic that could match the ambition and the commercial potential of The Birth of a Nation” (Condon, 243). Kickham’s Knocknagow must have seemed a natural choice of text for filmatization. Frequently described as “the most famous of all Irish stories” (Irish Limelight, May 1917, 6), it had gone through many reprintings and had recently been translated into Gaelic by Micheál Breathnach in 1906 and adapted for the stage by R. G. Walshe in 1915. The novel’s nationalist credentials were impeccable, and, perhaps as importantly, it commanded the moral respectability and cultural prestige needed by Irish filmmakers for whom approval by the Catholic Church had decisive commercial implications. “[It] must be gratifying to the Catholic Truth Society, the Vigilance Committee, and other kindred organisations,” observed the Freeman’s Journal, “to know that the Film Company of Ireland has proved their contention that pictures can be moral and clean and still be as attractive to the public as the slushy, sensational, sensual output that is so often dumped on this Irish market” (28 January 1920, 5).[14] In a similar vein, the Bishop of Limerick told an audience in 1924 that “they had an instance of how the people’s minds could be elevated in the films of Knocknagow and the recent Irish Pilgrimage to Lourdes” (Southern Star, 15 November 1924, 7). Indeed, as Maryanne Felter and Daniel Schultz have shown, the FCOI exploited a large network of sympathetic Catholic clergy when distributing Knocknagow in the United States (Felter and Schultz 2004, 35–9, and Felter and Schultz 2006).

Kickham’s novel is a study of class relations against the backdrop of land clearances in or around the late 1840s. Its main setting is the Tipperary village of Kilthubber and neighbouring hamlet of Knocknagow, with additional scenes in Clonmel, Dublin, and the seaside resort of Tramore.[15] Notwithstanding its frequent digressions and authorial interpolations, the narrative is essentially a romance (or cluster of romances) mapped onto a larger drama of social and economic transformation. Kickham refers to the work of Charles Lever, Washington Irving, and Charles Reade, and his regional subject-matter has been compared to George Eliot’s Adam Bede (1859) and Émile Erckmann and Alexandre Chatrian’s tales of Alsace-Lorraine, but modern readers are more likely to see Knocknagow; or, The Homes of Tipperary as a cross between early Dickens and Scotland’s dialect-inflected Kailyard School. The novel’s theatricality is evident not only in Kickham’s reliance upon the conventions of mid-nineteenth-century melodrama but also in the many scenes of spectatorship and, not least, the use of Henry Lowe, a prosperous Englishman, as a narrative proxy for audiences who are implicitly presumed to share his ignorance of Irish rural life, the Gaelic language, and Catholicism.

There are two main groups of characters. The first are peasants and small tenant farmers: the novel’s hero, Mat Donovan, and his sister Nellie; Phil Morris, an old revolutionary, and his daughter Bessie, Mat’s sweetheart; Phil Lahy, an alcoholic tailor, his wife Honor, son Tommy, and daughter Nora, who is dying of tuberculosis; Billy Heffernan, a turfman and musician, who is in love with Nora; Tom Hogan, a tenant who improves his land only to be evicted from it, and his wife and children, Jimmy and Nancy; and Mick Brian, another evictee, and his family.[16] The second group is the local gentry: Dr Kiely, an Irish nationalist, and his children Grace, Hugh, and Edmund; Bob Lloyd, a bachelor farmer, his sister Henrietta and brother Lory; and, most importantly, Maurice Kearney, a benevolent but financially inept large tenant farmer, his wife and children, Richard, Ellie, Grace, and Mary. Mary Kearney is wooed by Henry Lowe, English nephew of the absentee landlord Sir Garrett Butler, and then by Arthur O’Connor, a young seminarian who abandons his theological studies to become a doctor. Shuttling among them all are three sympathetic local priests; Isaac Pender, a villainous land agent, his son Beresford and their henchman Darby Ruadh; Sergeant Baxter, an English dragoon; and the novel’s two comic principals, Barney “Wattletoes” Broderick, the village buffoon, and Peg Brady, a gossip who has tried to catch Mat’s eye. The novel ends in near-perfect closure with a cascade of marriages: Mat and Bessie; Billy and Nellie; Arthur and Mary; Grace and Hugh; Edmund and Garrett Butler’s daughter; and Barney and Peg. Villains are punished, meanwhile, and bachelors dismissed. Henry Lowe leaves for India, Richard Kearney joins the army as a surgeon, Pender goes to jail, and at least some of the heartless large tenant farmers are themselves evicted. The Lahys and Morrises ultimately emigrate to the United States, where they are portrayed as living in comfort.

As even this thumbnail sketch indicates, Kickham’s sprawling novel, with its huge cast and long passages of dialect conversation, presented a huge challenge to the FCOI. Scholarly discussion of the company’s choices and omissions has hitherto centred largely on their political implications. For Taylor Downing, the “cumbersome and complex” structure of the film, which offers “no political analysis of Ireland’s problem,” is a reflection of the “prosaic form of the original novel” (Downing, 43). For Kevin Rockett, by contrast, the FCOI’s muting of Kickham’s critique of Kearney as a large farmer suggests a deliberate accommodation to the ideological agenda of a Sinn Féin-led nationalist movement now pursuing cross-class unity (Rockett 1988, 20). And in a detailed and thoughtful analysis of the film as an adaptation, Ruth Barton argues that Knocknagow offers a romantic-pastoral and reformist political programme that, like its rambling and episodic form, broadly mirrors Kickham’s text (Barton, 24). Even so, the sheer extent of the differences between film and book suggests that the FCOI may in fact have taken a rather more radical approach to the task of adaptation.

One of Knocknagow’s opening titles announces: “This story, in a series of episodes, depicts the joys and sorrows of the simple kindly folk who lived in the homes of Tipperary seventy years ago” (Intertitle 4). This is no understatement: the film is extremely episodic. Fewer than half of its scenes presuppose a strongly causal relation that the intertitles seek to convey, among them Barney’s failure to bring a letter from Arthur to Mary; Mick Brian’s discovery of a hidden gun; Pender’s framing of Mat for robbery; Bessie’s romance with a dragoon; and Peg’s efforts to divert Mat’s affections. Often premised on incidents and relationships not depicted in the film, and making minimal use of cutaways and flashbacks, they are in places almost impossible to follow. In turn, many of the film’s other scenes, including those in which Mat ploughs using a horse-team and Billy dreams about his dying sweetheart in happier days, are less “episodes” than stand-alone vignettes. Often single-shot, they are strongly reminiscent of tableaux or short melodramatic sketches. To these can be added what Barton identifies as the film’s “set-pieces” of peasant life—the hurling match, the country wedding, the travelling peep-show (Barton, 31)—and a host of other static sequences or non-narrative “attractions,” including the fife and drum band’s parade, Barney’s bet about having “the ugliest foot in Ireland” (Intertitle 28), Mat taking leave of his sister, and direct addresses to the audience such as the following:

FELLOW IRISHMEN. Let us take to heart the lesson in the vindication of Mat Donovan’s honor and in the proof of his innocence. We must cultivate under every dire circumstance, patience and fortitude to outlive every slander and to rise above every adversity. We are a moral people, above crime, and a clean-hearted race must eventually come into its own, no matter how long the journey, no matter how hard the road. (Intertitle 155)

Knocknagow is, then, an episodic adaptation of an already episodic novel (for a summary of the film’s plot see Appendix A). “No mere synopsis can tell the story the Knocknagow,” conceded the FCOI’s promotional leaflet,[17] and the Irish Limelight issued a candid warning: “To appreciate this filmed version of Knocknagow one must first have read the book” (April 1918, 5). To be sure, the novel was still in print in 1918 and its themes and characters remained widely known. But it is very doubtful whether many of the film’s first audiences had actually read it, either in part or cover to cover. The Anglo-Celt’s reviewer described it as “a book that was so dear to the older generation” (2 March, 1918, 14). Indeed, in the preface to his controversial novel The Valley of the Squinting Windows (1918), Brinsley MacNamara makes a striking observation:

In the parlor, as they call it, or best room of every Irish farmhouse, one may come upon a certain number of books that are never read, laid there in lonely repose upon the big square table on the middle of the floor. A novel entitled Knocknagow is almost always certain to be amongst them, yet scarcely as the result of selection, although its constant occurrence cannot be considered purely accidental. There must lurk an explanation somewhere about these quiet Irish houses connecting the very atmosphere with Knocknagow. A stranger, thinking of some of the great books of the world, would almost feel inclined to believe that this story of the quiet homesteads of Ireland must be one of them, a book full of inspiration and truth and beauty, a story sprung from the bleeding realities which were before the present comfort of these homes. Yet for all the expectations which might be raised up in one by this most popular, this typical Irish novel, it is most certainly the book with which the new Irish novelist would endeavor to contrast his own. For he would be writing of life, as the modern novelist’s art is essentially a realistic one, and not of the queer, distant, half pleasing, half saddening thing which could make one Irish farmer’s daughter say to another at any time within the past forty years:

“And you’d often see things happening nearly in real life like in Knocknagow. Now wouldn’t you?” (MacNamara, ix)

Ubiquitous yet never read, unrealistic yet never dated, the great Irish novel as described by MacNamara puts the FCOI’s adaptation in a rather different light. While the sheer difficulty of compressing Kickham’s sprawling tale was likely compounded by the company’s relative inexperience in filmmaking, the FCOI’s adaptation is best understood as an attempt to give audiences a filmic version of the novel as they knew it, that is, as a loose collection of memorable characters and situations, rather like how The Pickwick Papers or Ulysses were (and are) known to their respective publics. Where the film does depart substantially from the original, it is generally for the purposes of narrative concision, and, as might be expected, such departures include sizeable cuts that further accentuate the film’s episodic character. A long subplot involving Sir Garrett Butler and his daughter is excised, as is a romance between Billy and Mat’s sister Nellie. Likewise, Henry Lowe is displaced as the focalizer because many of his insights in the novel take the form of flashbacks, while the eventual union of Billy and Nellie is omitted because it requires too long a passage of time. There are additions, too. Arthur is shown meeting Mary at Tramore, and Butler is shown eating Christmas breakfast with the Kearneys because these scenes, which are absent from the book, introduce key protagonists while also economically establishing their most important relationships.

That audiences knew Knocknagow primarily as a collection of episodes and at second hand is further suggested by the fact that contemporary reviewers failed to detect any of the discrepancies in the film adaptation, even those which removed key elements of suspense in the novel, such as the mystery of unidentified footprints in the snow beneath Mary’s window, and the “robbery” of Pender, which is only later revealed to be a frame-up.[18] There are, moreover, numerous inconsistencies in the spelling of names: “Jemmy,” “Brodherick,” “Brien,” “Nelly,” “Bessy,” and “Norah” in the novel become Jimmy, Broderick, Brian, Nellie, Bessie, and Nora in the film. As two examples will suffice to show, this mixture of disregard for the original in places and scrupulous fidelity to it elsewhere is a feature of the FCOI’s Knocknagow.

The first is the death of Nora Lahy. As friends and family kneel at the dying woman’s bed, behind which a bird-cage is clearly visible, she suddenly opens her eyes (see fig. 8 ) . An intertitle announces: “Nora Lahy hears a call and the linnet that never sang before, sends forth its thrilling notes” (Intertitle 141). All turn to watch the bird, while another intertitle explains: “As the song of the linnet ceased, Nora Lahey [sic] was among her kindred angels” (Intertitle 142). Realizing that she has expired, they are overcome with grief. The scene closes with a exchange between Billy and Nellie: “‘I loved her Nellie, ah, how I loved her!’ . . . . ‘Sure, I know Billy, we all loved her’” (Intertitles 142 and 143).

Irish audiences would easily have identified this highly emotional scene with MacNamara’s “things happening nearly in real life like in Knocknagow” (MacNamara, ix). Its special status is underscored by the fact that, at almost ten minutes, it is by far the longest scene in the film. Effectively an Irish version of the death of Little Nell in Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop (1841), it has a drawn-out, static composition that recalls contemporary theatrical tableaux, devotional works of art, and book illustrations. Unusually, however, the intertitles offer a version of actual dialogue in the book:

“Nelly,” returned Billy Heffernan, “I was dead fond uv her.”

“Every wan was fond uv her,” said Nelly Donovan. . . . (Kickham 1887, 526)

Although the novel is quoted verbatim in a few other intertitles (e.g. “As the song of the linnet ceased . . . Norah Lahy was among her kindred angels” [Kickham 1887, 525; cf. Intertitle 142]), the screenwriters would hardly have dared to Hollywoodize Kickham’s poignant understatement in this way if contemporary audiences were familiar with the wording of the original text. The same point holds for the linnet’s miraculous warbling, which is actually a conflation of three separate incidents in the novel: a poetic description of Nora listening to the linnet’s “low, sweet, wondrously varied song”; Nora’s final breath, when “the old linnet in the window began to sing”; and the moment, a year later, when Billy and Nellie realize their feelings for each other: “The old linnet began to sing that low sweet song of his; though his voice had never before been heard except in the day-time” (Kickham 1887, 57, 525, 564).

An even more substantial discrepancy relates to the English soldier. In the novel, the dragoon, identified by name as Sergeant Baxter, is portrayed sympathetically. He observes Mick Brian’s wretchedness with “surprise and something like pity” and accompanies Billy to Clonmel, where he treats his new “friend” to a drink, calling them “comrades on the road,” and is treated by Billy in return (Kickham 1887, 262, 269, 268). When he sees the dragoon near Bessie’s house, Mat’s first instinct is to beat the “mane dog” (Kickham 1887, 503) but he calms down after realizing that Baxter is only talking to Peg. Baxter is last seen asking Billy about the fate of Knocknagow, whose inhabitants he has presumably helped to evict, with “a mean, shame-faced look, as if he felt he was despised, and deserved to be” (Kickham 1887, 531). In the film, by contrast, the dragoon is merely an objectionable rival for Bessie’s affections. Billy tries to shun him when they meet in Clonmel, and after Mat beats him for loitering near Bessie’s house, he revenges himself by helping Pender to frame Mat for robbery (Intertitle 125).

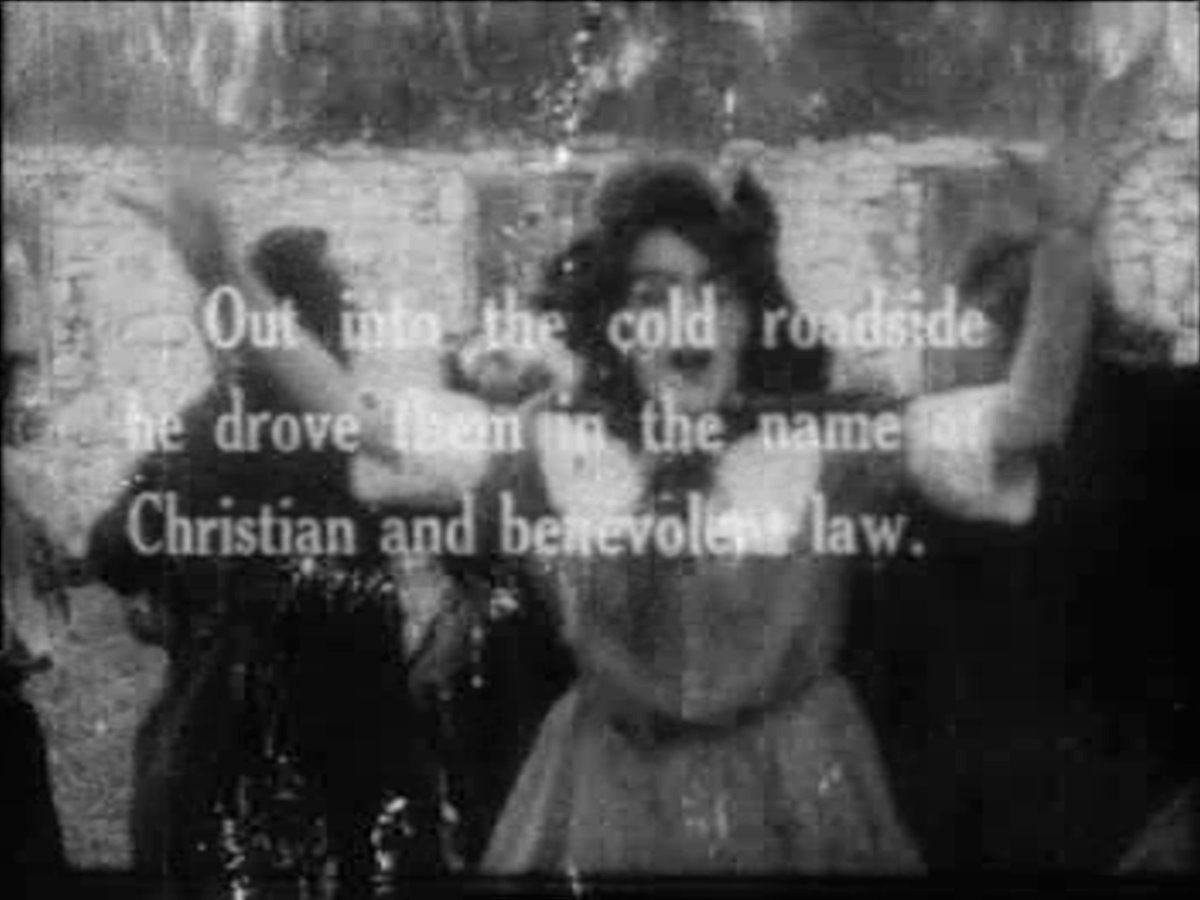

The spectacle of an English soldier being soundly beaten by an Irishman can only have delighted Knocknagow’s audiences in Ireland and the United States; the Bioscope, while complaining of the scene’s “biassed tone,” noted carefully that it depicted a dragoon “after he has left the army” (16 October 1919, 58). Yet no reviewer remarked upon the fact that this politically controversial scene not only appears nowhere in the novel but runs contrary to Kickham’s apparent desire to portray the English working classes as largely deceived by their masters about the situation in Ireland. The beating of the dragoon is, rather, how audiences may have “remembered” the original—just as they may have “remembered” the climactic eviction scene, also notably absent from the novel, in which Mick O’Brian’s cottage is burned (see fig. 9 , fig. 10 , fig. 11 ).[19] To paraphrase the imaginary farmer’s daughter quoted by MacNamara, it’s just the kind of thing Mat would do.

Drawing firmer conclusions about the FCOI’s procedure in adapting Kickham’s novel is problematic because the only surviving print of the film bears the traces of several rounds of extensive editing. An opening intertitle (fig. 12) refers to two copyright holders: Kickham’s publisher, whose claim is somewhat obscure; and Ellen Sullivan, wife of producer James Mark Sullivan, whose name also appears on a contemporary typescript of the intertitles now held at Cornell University (see Appendix G). The FCOI’s advance publicity described the film as “adapted by Mrs N. F. Patton” (Irish Limelight, April, May, and June 1917, back covers), and the version screened in Ireland in 1918 also appears to have credited the screenplay to “Mrs. Patton, a Dublin lady” (Clonmel Chronicle, 2 February 1918, 5). Although the circumstances under which copyright was transferred to Ellen Sullivan are unknown, her death in May 1919 may have prompted the author of the Cornell typescript to remove her name from the copyright page and replace it with the statement: “The rights of all productions of the Film Co. of Ireland are owned and controlled by The Irish Film Co. of America.” If so, then the surviving print of Knocknagow must date from mid-1919 or later. It is clearly not the eight-reel (8,700 feet) print shown to Irish trade and general audiences in spring 1918, which ran for at least an hour longer.

The Cornell typescript (with manuscript annotations) describes extensive revisions to a seven-reel print which contained intertitles absent from the surviving version of Knocknagow. The typescript also gives instructions for the creation of entirely new intertitles, none of which appear in the surviving version, and for the “remaking” of others, some of which do appear, in this emended form, in the surviving version.[20] The typescript contains no instructions for the making of any new “Art” intertitles—that is, decorated with an artistic design—but some of the existing “Art” intertitles which it marks for deletion do nonetheless appear in the surviving print (e.g. Intertitles 106, 124, and 143; see Appendix H). The surviving print thus appears to have derived from a version of the film (possibly the eight-reel version shown in Ireland in 1918) that predates the seven-reeler version described in the Cornell typescript. However, the editor of the surviving version evidently had access to the new intertitles which the Cornell typescript had commissioned for the film’s American distribution. The evidence is admittedly circumstantial but it may well be that the surviving print of Knocknagow is the six-reel version, incorporating material from a longer American print, that was reviewed by the British Bioscope in October 1919 and shown in Manchester in early January 1920.[21] Whatever the case, the oldest complete print of an Irish-made fiction film appears to be the result of a fascinating interaction between editors and audiences on both sides of the Atlantic.

Reappraising Knocknagow

As one of only three films to survive from Ireland’s first fully-fledged production company, Knocknagow is a precious resource for all those interested in Irish cinema. It features the screen debut of the great Irish actor Cyril Cusack, who plays the part of Mick Brian’s young son (see fig. 13) . It includes rare footage of a real hare-coursing event and one of the earliest cinematic representations of the Irish sport of hurling. Its depiction of Mat Donovan’s transatlantic quest to find his sweetheart is perhaps the first attempt to portray the United States in Irish cinema. Not least, it documents the efforts of prominent Irish actors as well as local amateurs to record a tale of national and international significance against the dramatic backdrop of Tipperary’s Slievenamon and Golden Vale.

For Knocknagow is a veritable hymn to Tipperary. Film in 1918 had not entirely shaken off its magical aura, and the conviction that moving pictures were not merely representations but also records of presence was especially pronounced in the case of landscape. The FCOI followed other companies of the time in playing up its use of Irish locations, such as Glendalough in The Food of Love, Wicklow in Paying the Rent, and the tourist sights included in its Serial of Twenty Irish Scenics (fig. 14) . Another of its first films had been titled The Girl from the Golden Vale (1916), and the Freeman’s Journal noted approvingly of Paying the Rent: “The story is enacted amid familiar scenes in Wicklow, ‘The Garden of Ireland,’ at Stepaside, in the shadow of our Dublin Mountains, at the famous Irish Derby, where Mr. Arthur Sinclair appears in the Ring in all the glory of full ‘make up’” (Freeman’s Journal, 9 September 1920, 6). Yet only Knocknagow premiered in the very spot where it had been produced, as if in fulfilment of the promise trumpeted by the company on the covers of Irish Limelight in April, May, and June 1917: “The Production will embrace the very valleys and mountains of Tipperary where Kickham laid his famous story” (emphasis added).

Fetishizing Irish locations was nothing new, of course. In 1914, Kalem shipped several tons of earth from the Collen Bawn Rock to New York, putting it into trays to be distributed with its reissue of The Colleen Bawn (USA 1911, dir. Sidney Olcott) so that patrons might literally stand on Irish soil prior to the screening (Slide, 42–3). In turn, Killester Productions assured viewers of In the Days of St. Patrick / Aimsir Padraig (Ireland 1920, dir. Norman Whitten) that “Many of the scenes were taken on the traditional spot recorded in history” (intertitle), and attached footage of Irish pilgrims, some on their knees, ascending Croagh Patrick in 1919, as well as shots of prominent Irish clerics. And the FCOI filmed its historical drama Willy Reilly and His Colleen Bawn at St. Enda’s School, a icon of Irish nationalism, even though the building postdated the period in question by forty years.

Knocknagow offered audiences, in other words, a kind of secular pilgrimage to Kickham country.[22] Not unlike the travelling peepshow whose views prove so irresistible to Barney, the film contrives to make Slievenamon visible in countless scenes, even those which take place inside the Lahys’ cottage. The mountain’s presence for audiences would have been further actualized by the live accompaniment of “Slievenamon,” now a Tipperary anthem, at screenings of the film in Ireland and the United States. Indeed, it ought perhaps to be described as the film’s presiding spirit. As Mat, in an exchange absent from the novel, declares from his prison cell: “If this window only faced old Slievenamon, Billy, I could stand this imprisonment better” (Intertitle 147).

It is with all of the above in mind that the following essays have been sought for this special issue of Screening the Past on “Featuring the Nation: Knocknagow and the Film Company of Ireland.” The range of their subjects attests to the complexity of Knocknagow’s production and reception history as well as to the diversity of issues with which the film engages. Kevin Rockett has situated the FCOI and Knocknagow in the context of early filmmaking in Ireland and the accelerating pace of the struggle for Irish independence. Daniel Schultz and Maryanne Felter have uncovered new evidence of producer James Mark Sullivan’s ties to the Irish Republican Brotherhood and involvement in Irish nationalist intrigues against Britain. Denis Condon has combed contemporary newspaper archives in order to reconstruct the terms of Knocknagow’s reception by Irish audiences in 1918. Gary D. Rhodes has documented the importance of the FCOI’s productions for American perceptions of Ireland and the Irish. Seán Crosson has revealed the connections between Knocknagow’s sporting scenes and early-twentieth-century discourses on nationalism and masculinity. And Christopher Natzén has compared Knocknagow with contemporary Swedish cinema in order to illuminate its conspicuous use of poems, songs, and music. Collectively, they invite us to reappraise an Irish cinematic landmark whose production and reception are deeply intertwined with international perceptions of Ireland, its past, and its future.

Images

Figure 1. Hearne’s Hotel, Clonmel. Image courtesy of Johnny Donovan Photography.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4. The Westgate, Clonmel. Image courtesy of Johnny Donovan Photography.

Figure 5. Christmas Day parade; Carrick Street, Mullinahone. Image courtesy of Johnny Donovan Photography.

Figure 6. Ned Brophy’s wedding; Carrick Street, Mullinahone. Image courtesy of Johnny Donovan Photography.

Figure 7. Kilthubber Parish Church; St Michael’s Parish Church (demolished 1965) c.1900, Callan Street, Mullinahone. Source: http://www.mullinahone.net.

Figure 8.

Figure 9.

Figure 10.

Figure 11.

Figure 12.

Figure 13.

Figure 14.

Works Cited

Newspapers:

Anglo-Celt (Cavan).

Bioscope (London).

Boston Daily Globe.

Clonmel Chronicle.

Evening Herald (Dublin).

Evening Press (Dublin).

Evening Telegraph (Dublin).

Evening Star (Waterford).

Freeman’s Journal (Dublin).

Irish Independent (Dublin).

Irish Limelight (Dublin).

Manchester Guardian.

Meath Chronicle.

Nationalist (Clonmel).

Nenagh Guardian.

Southern Star (Skibbereen).

Watchword of Labour (Dublin).

Other:

Barton, Ruth. 2004. Irish National Cinema. London: Routledge.

Comerford, R. V. 2004. Charles Joseph Kickham (1828–1882). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/15509. Accessed 1 October 2011.

Condon, Denis. 2008. Early Irish Cinema, 1895–1921. Dublin: Irish Academic Press.

De Búrca, Séamus. 1945. Knocknagow, or The Homes of Tipperary.

—–. 1953. Phil Lahy. Dublin: P. J. Bourke.

Downing, Taylor. 1979/1980. The Film Company of Ireland. Sight and Sound 49.1 (Winter): 42–5.

Felter, Maryanne, and Daniel Schultz. 2004. James Mark Sullivan and the Film Company of Ireland. New Hibernia Review 8.2 (Summer): 24–40.

—–. 2006. Selling Memories, Strengthening Nationalism: the Marketing of Irish Silent Films in America. Canadian Journal of Irish Studies 32.2 (Fall): 10–20.

Fennelly, James, et al, eds. n.d. [1982]. Knocknagow Remembers. Privately printed.

Kickham, Charles J. 1869. Sally Cavanagh; or, The Untenanted Graves: A Tale of Tipperary. Dublin: W. B. Kelly.

—–. 1886. For the Old Land; or, A Tale of Twenty Years Ago. Dublin: M. H. Gill.

—–. 1887. Knocknagow; or, The Homes of Tipperary. Dublin: James Duffy. First published in 1873.

—–. 1906. Cnoc na nGabba. Trans. Micheál Breathnach. Dublin: Connradh na Gaedhilge.

MacNamara, Brinsley. 1919. The Valley of the Squinting Windows. First published in 1918. New York: Brentano’s.

Maher, James, ed. 1942. The Valley Near Slievenamon: A Kickham Anthology. Kilkenny: Kilkenny People.

Rockett, Kevin. 1988. The Silent Period. In Cinema and Ireland, ed. Kevin Rockett, Luke Gibbons, and John Hill, 3–50.

—–. 2004. Irish Film Censorship: A Cultural Journey from Silent Cinema to Internet Pornography. Dublin: Four Courts.

Slide, Anthony. 1988. The Cinema and Ireland. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Walshe, R. G. 1917. Knocknagow: A Drama in Three Acts Based on the Famous Irish Novel by Charles J. Kickham. First performed in 1915. Dublin: James Duffy.

[1] See Slide, 11–14; Rockett 1988, 16–32; Barton, 23–31; Condon, 236–43.

[2] Julius Benedict’s opera The Lily of Killarney (1862) was based on The Colleen Bawn, a play by Dion Boucicault, who also wrote its libretto; it was made into a film in 1923 (Slide, 17)

[3] “Film Company Raided. A large party of military participated in a raid on the offices of the Film Company of Ireland on the top floor of the premises, 34 Dame St, Dublin, at four o’clock on Monday afternoon, and for some time searched desks, drawers, and letter files. When two officers in charge of the raiders entered the offices, they were confronted by a small office boy, who was asked if he knew where the directors or staff were. He said he did not. He was also asked if he was Irish, and his reply was ‘Yes.’ Bayonets were then used to prise open drawers; presses were ransacked, and correspondence examined. During these operations the office boy was placed between two fully equipped sentries. When leaving the building the military party took with them a number of letters. During the progress of the raid cordons were drawn across the street outside, and all traffic suspended” (Nenagh Guardian, 4 December 1920, 4).

[4] See Slide, 39–45; Rockett 1988, 7–16; Barton, 19–23; and Kevin Rockett’s contribution to this number. The Irish Film Institute has recently released an excellent DVD containing all eight of the company’s surviving films, The O’Kalem Collection: 1910–1915 (IFI and BIFF Productions, 2011).

[5] “More Details of ‘Knocknagow,’” Evening Press (Dublin), 7 July 1965, n.p.

[6] See also James Maher (ed), The Valley Near Slievenamon: A Kickham Anthology (1942).

[7] Mullinahone is often misidentified as the birthplace of Kickham, who was in fact born in or near Cashel, County Tipperary (see Comerford).

[8] In a letter to the Irish Times, Séamus de Búrca, author of two stage adaptations of Knocknagow (de Búrca 1945 and 1953), recalled having assisted at a screening of the film in 1928 at which “Brian McGowan . . . performed and sang in a Prologue to the film” (Irish Times, 25 March 1975, 9).

[9] A reference by Dublin’s Evening Telegraph on 13 December 1919 to Knocknagow having already “showed for three weeks” in Boston raises a question mark about whether it had been exhibited there previously.

[10] Knocknagow was distributed in the United States by the Irish Film Company of America until 1922. A contemporary advertisement for this Massachusetts-registered company indicates the presence of prominent Irish-American businessmen on its board: President—Francis J. Flynn (Boston Globe); Vice-President—Bernard J. Heaney (Trustee, Hibernian Savings Bank, Boston); Treasurer—Joseph O’Mara (Sullivan’s brother-in-law); and Directors Timothy J. McKeon and Peter J. Mahan. Information courtesy of Maryanne Felter. See also Felter and Schultz 2004, 33–4.

[11] Evening Herald, 15 April 1918; Irish Independent, 26 April and 26 October 1918; Irish Limelight, July 1918; Evening Herald, 13 May 1918; Evening Star, 1 April 1918; Irish Limelight, May 1918, 13; Meath Chronicle, 27 July 1918, 6; Irish Limelight, July 1918. See Condon, 113–14.

[12] “Concert in Aid of [Irish Republican Prisoners’] Dependents’ Fund at Bohemian Cinema [Dublin]. The screen selection was composed of a 2-part drama, ‘The Moonriders,’ a 2-part Sunshine comedy, a 5-part film by the Film Company of Ireland, ‘The Girl of Glenbay,’ [i.e. The Girl of Glenbeigh, 1917] and a section showing the I.R.A. in training, besides clever demonstrations in favour of Irish manufactures” (Freeman’s Journal, 27 Oct 1921, 3).

[13] Billed as “enormously successful,” this now lost adaptation premiered in Clonmel sometime before April 1915 before playing at several venues in Dublin: Abbey Theatre (22–24 April 1915; 2–4 March 1916); Queen’s Theatre (9–15 July, 21–27 October 1918; 5 August and 12, 13, 15 September 1921; 15 October 1923); Father Mathew Hall (13, 18, 21 Nov 1921; 8, 13, 14, 15 May and 17, 24 Aug 1922). In Nenagh, the play was performed on 1 Oct 1918, barely a month after a screening of the film. Condon notes of the play’s premiere in Clonmel: “Given that [the] FCOI also decided to have a premiere in Clonmel, at Magner’s Theatre, contemporary observers could be forgiven for believing that a link existed between the two works” (Condon, 114).

[14] On film censorship in Ireland at this time, see Condon, 226–36, and Rockett 2004.

[15] One of several anachronisms. Prior to the railway’s arrival in 1856, Tramore was a sleepy fishing village; its Doneraile Walk promenade, where Kickham presents Henry Lowe first sighting Miss Butler, was built in 1867.

[16] Except where indicated, the spelling of names here follows that of the film’s intertitles.

[17] A copy of this page is preserved in the Irish Film Archive.

[18] Condon points out that the Irish Limelight wrote about the film adaptation of Knocknagow in a way that presumed its readers’ familiarity with the novel (Condon, 246). Yet the same reviewer misidentifies Hogan’s son as returning from the Crimean War (1853–56), when Kickham in fact refers to him fighting for England in “hot sun” (Kickham 1887, 522), probably the Second Anglo-Sikh War of 1848. (India is mentioned on several occasions in the novel.)

[19] The film’s unusual superimposition of intertitle text may have been inspired by D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (USA 1916).

[20] The surviving print of Knocknagow includes several numbered intertitles bearing a decorative “Keltik” logo. Their numbering suggests that these intertitles appear in their original sequence but were created for a different, and probably longer, version of the film. For example, Intertitles 170, 172, and 176 are numbered “196,” “197,” and “202,” respectively.

[21] This would also confer an additional significance upon the surviving print’s long address to viewers as “FELLOW IRISHMEN” (Intertitle 155).

[22] Memories of Kickham run deep in Mullinahone. In 1982, a Knocknagow-themed pageant, including a re-enactment of Mat’s epic hammer-throwing contest, was held in the grounds of nearby Killeaghy Castle (Fennelly et al.), and to this day locals can point to the spot where the film’s eviction scene was shot.