Abstract

“Could this be Lord Cholmondeley?” wonders Rose Randall, The Rose of Rhodesia’s magazine-reading heroine, when a scruffy stranger arrives at her door. Rose’s weakness for romantic fiction is an obvious vehicle for comedy, but is it just coincidence that her magazine story is also set in Rhodesia? As this essay shows, the fact that the film’s Rhodesian heroine is also reading a romance about Rhodesia says much about the colony’s special status in British and American popular culture. Despite having few white women settlers, Rhodesia in the 1910s and 1920s became the focus of a literary vogue in which novels featuring independent women sold in the millions and were adapted for theatre and the screen. Like The Rose of Rhodesia, they created a virtual Rhodesia of individual responsibility and freedom that held a special appeal for women readers in Britain and the United States.

……..

Pity poor Miss Randall, the workaday heroine of The Rose of Rhodesia (1918). Motherless and isolated, she shares her tumbledown shack with a ne’er-do-well father whose drinking threatens to ruin them both. Small wonder, then, that Rose is an avid reader of romantic fiction. And what fiction! In nine linked intertitles, almost a tenth of its total number, the film gives us a privileged insight into how she whiles away her time with the exploits of dashing Lord Cholmondeley. With Rose, we read how the aristocrat, driven from England by an affair of the heart, proceeds to South Africa by luxury liner and thence to Rhodesia by special train (Intertitles 45-46). Arriving at the mellifluous village of Seijaduntella, he checks into its only hotel under the name Carl Standington “in order that the world might forget him utterly” (Intertitle 54). There, we learn, he spends a day touring the area by mule, smokes some of his “famously rich Havanas,” and tucks into a springbok steak (Intertitles 55, 57, 64). In the final installments, he leaves the village, never to return, after spending the night with a local girl named Betty Beetle, whose lapse of judgement makes marriage an impossibility (Intertitle 81). The moral for young women is spelled out: “If Betty had known the meaning of chastity, who knows? Perhaps everything would have turned out differently…” (Intertitle 82).

Anyone who has read much early-twentieth-century romantic fiction will recognize this as the opening of a novel. Moral convention precludes either the libertine Cholmondeley or the wanton Betty from being its main protagonist, a role that will most likely fall to the orphaned offspring of their liaison, perhaps an attractive but impoverished heroine who reclaims her birthright after a succession of adventures. Whatever the case, Rose is assured of a thrilling read. But why has she chosen a romance set in her own dreary corner of the empire? After all, suspending disbelief is always easier when one doesn’t know the terrain at first hand. (The Rose of Rhodesia, observed The Bioscope, was “likely to appeal” to audiences in the industrial cities of northern England [20 November 1919, 123].) Surely Paris or the South Seas would be more plausible objects for the daydreams of an unhappy girl in Rhodesia?

Maybe the story appeals to Rose precisely because it is a fantasy version of her own everyday world of tough springbok steaks and lecherous white settlers in a dull frontier outpost. Or perhaps the figure of the incognito aristocrat, a hardy perennial in colonial fiction of this era, gratifies Rose’s feelings of class and racial superiority, feelings that have perhaps been frustrated by her inability to afford a servant—in contrast to her neighbours, the Morels, who are brought tea by a servant in white linen—a humiliating fate, to be sure, for white settlers drawn to Africa by the promise of cheap domestic labour. During the hunting episode, as the modern viewer wincingly notes, she does not hesitate to use Mofti as a footstool in a grotesque performance of gentility (Fig. 12.1).

Although the intertitles’ layout corresponds to that of a book, its physical dimensions and advertisements for Epp’s Cocoa and Swan Vesta Matches indicate that Rose is actually reading an illustrated magazine (Fig. 12.2). The distinction is significant. The magazine helps to make Rose into an object of sympathy for viewers, who share her newly globalized literary tastes, and recognize in her one of those ordinary-yet-heroic girls so beloved of popular serials. Yet this is recognition tinged with pathos. Cheaper and less demanding than a book, her reading matter attests to a profounder lack of freedom. Even among white colonists, The Rose of Rhodesia reminds us, reading is gendered and hierarchical: for men, official letters, newspapers of record, and the Bible; for women, romantic ephemera. (On the one occasion when she does hold a newspaper, Rose is apparently bringing it to her father.) She has no more chosen this media-created identity than she has chosen to be poor, motherless, uneducated, and unmarried. Rose, we might say, is heroic despite being a magazine reader.

The romance itself performs a number of functions. Most immediately, it mocks the implausible storylines and florid prose style of genre fiction—“His dark eyes were glowing beneath their dark lashes” (Intertitle 45)—from a perspective that is male and empowered. At the same time, it engages our sympathies on behalf of those for whom mass-produced sentimentality is, in Marx’s famous phrase, the heart of a heartless world. And with good reason, too, for there must have been plenty of Rose Randalls in the first audiences of The Rose of Rhodesia, also a melodrama whose protagonists are motivated by considerations of duty, noble blood, sacrifice, and romantic intrigue; whose landscape is populated by mysterious strangers and lonely frontier women; and whose narrative is structured around that matrix of wealth, honour, and imperial opportunity that receives its definitive treatment in P. C. Wren’s French Foreign Legion tale Beau Geste (1924).

In presenting Cholmondeley’s story through point-of-view shots of stylized pages, the magazine intertitles are evidently meant to evoke Rose’s state of mind. As such, they exemplify silent cinema’s growing repertoire of representational techniques: the creation of suspense by crosscutting (the diamond theft); the manipulation of time by double-exposure (Ushakapilla’s dream); and the intensification of emotion by close-up (Winters frowning in the bar). And these metonyms of serial publication and their elliptical conjunctions (“…”) also symbolize the deferral of closure that defines the romantic feuilleton. But in mirroring Rose’s own emotional stasis they differ from the film’s other intertitle facsimiles in one key respect. Unlike the newspaper advertisements for the Rose Diamond, or the colonial administrator’s letter to James Morel, these metafictional texts do not reproduce information that is indispensable for the plot. (Were Rose reading something else—say, London society news—viewers would still understand that she is longing for romance and an escape from poverty.) Rather, their main function seems to be the simulation of a particular reading experience.

Now, viewers of The Rose of Rhodesia today may well be puzzled by its title. No part of the film was made in the territories of Northern and Southern Rhodesia that comprise modern-day Zambia and Zimbabwe. Neither its cast nor its production company was Rhodesian, and the film was never screened in the colony where most of its action supposedly takes place. References to Rhodesia are also almost entirely absent from the cinematic narrative. Viewers were presumably not meant to be disoriented by the sudden appearance in a Rhodesian pub of Fred Winters, last seen face down in a very different kind of watering-hole several hundred miles away in South Africa’s Karoo Desert, identified as such in Intertitle 38. In fact, although Rhodesia is mentioned obliquely in the intertitle expressing Mofti’s hope that Jack Morel will have “as many children as there are stones on the Matoppos hills” (Intertitle 89), full confirmation of The Rose of Rhodesia’s setting is withheld—in the only surviving print, at least—until the penultimate scene, when Ushakapilla congratulates Jack on having married “the most beautiful Rose in all Rhodesia” (Intertitle 114).

In every sense, then, the film’s Rhodesia is imaginary space, a colonial counterpart to that Wild West in which a gunslinger can ride from Dodge City to the Rio Grande by sundown. (In the real Rhodesia, lamented one settler, “women are as scarce as roses in December” [Page 1913, 147].) It would be logical to assume, in turn, that Harold Shaw chose this geographical cipher for its alliterative euphony with Rose, a name whose popularity is evident from the titles of numerous films of this period, among them A Rose of the Tenderloin(dir. J. Searle Dawley, 1909), in which Shaw himself had starred, and The Heart of a Rose (dir. Jack Denton, 1919) and The Sign of the Rose (dir. Harry Garson, 1919), both of which were advertised alongside The Rose of Rhodesia in the British trade press in late 1919. There is a flaw in this line of reasoning, however. If Shaw chose Rhodesia arbitrarily, why does he insist on telling viewers on two occasions (Intertitles 46 and 54) that Rose’s magazine story also takes place there? The magazine story has only secondary relevance for the plot, and if intended as comic irony at Rose’s expense, the joke is strangely laboured. No, something else is at work here, something related to the precise nature of the experience being simulated: a woman reading about Rhodesia.

As it happens, Rhodesia was a relatively familiar subject to readers in Britain and the United States in the first decades of the twentieth century. The spectacular and controversial invasions of Mashonaland and Matabeleland (later Southern Rhodesia) in the 1890s had been covered at length by the press, fuelling an outpouring of military memoirs, travelogues, and adventure novels as well as a cornucopia of ephemera that included magazine features, cartoons, commercial prospectuses, advertisements, postcards, magic lantern slides, stereoscopic photographs, and cigarette cards (see Appendix G). Given impetus by the mythologizing of its founder, Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902), Rhodesia’s presence in early-twentieth-century culture grew far out of proportion to the colony’s political or economic significance. Among the indirect consequences of this phenomenon was an international vogue for novels by Rhodesian women. Now all but forgotten by literary historians, these dramas of life on one of the last imperial frontiers briefly commanded huge audiences, their popularity boosted by screen adaptations and serialization in mass-circulation women’s magazines on both sides of the Atlantic.

This popular cultural context reveals the Cholmondeley sequence as more than just a clever mise en abyme or Chinese box effect in which the protagonist of a (cinematic) romance set in Rhodesia reads about the protagonist of a (literary) romance set in Rhodesia. By incorporating a magazine story about Rhodesia into its own narrative, the film recreated a reading experience with which female cinemagoers could identify. In the process, as we will see, it offered an oblique commentary on Rhodesia’s peculiar status in printed word and moving image as a repository for the fantasies and aspirations of women, not in Southern Africa, but in Britain and the United States. Far from being an empty signifier, this virtual Rhodesia had become firmly linked in the popular consciousness with a reinvention of feminine identity, one more profound than the name-changing impostures of male fugitives such as Cholmondeley and Winters.

Cosmopolitan Rhodesia

Even in the absence of precise sales figures, there is little doubt that Gertrude Page (1873-1922) and Cynthia Stockley (1877-1936) exerted a profound influence on how early-twentieth-century British and American readers thought about Rhodesia. Prolific and popular, these authors dominated the market for Southern African fiction, supplying dozens of novels and short stories to audiences whose appetite for romance and domestic drama set in Rhodesia and South Africa appeared well-nigh insatiable (see Donovan). “Few modern novelists have achieved such popularity as Miss Gertrude Page,” declared one British commentator (Authorship, 176), and in the United States Variety magazine reported that demand for Stockley’s Poppy (1910) had been so intense that “the presses could not keep up” (“Poppy” 1917). By 1919, the best-known of these novels, Page’s The Edge o’ Beyond (1908), was being puffed as a “world-famed book” of which “a million copies have been sold” (The Bioscope 30 October and 13 November 1919). Together with Page’s Love in the Wilderness (1907) and Jill on a Ranch (1922), and Stockley’s Virginia of the Rhodesians (1903) and Dalla the Lion-Cub (1924), it launched a new literary genre, the Rhodesian veldt novel, centred on the lives of women on the Southern African frontier—the very psychological and geographical terrain of The Rose of Rhodesia.

Both novelists were fortunate to be writing just after the boom in serial publication at the turn of the century, which had created a huge market for fiction in advertising-driven magazines that aimed predominantly, if not exclusively, at women. Page began her career in the early 1900s by submitting stories with titles such as “If Loving Hearts Were Never Lonely” and “The Mysterious Stranger” to The Girl’s Own Paper [1] , and by 1921 her work was appearing regularly in Alfred Harmsworth’s Hutchinson’s Magazine. (Bibliographic data is lacking but presumably she published in many others.) More is known of Stockley’s extensive magazine writing, which ranged from the short story “The Road to Tuli” in McClure’s Magazine for April 1912, where it was illustrated by the celebrated Frederic Dorr Steele, to the serialization of her bestselling novel Ponjola in Nash’s Magazine in 1923. Stockley’s name was most closely connected with William Randolph Hearst’s Cosmopolitan magazine, which serialized “April Folly” in 1918, Dalla the Lion-Cub in 1924, Three Farms in 1925, and Tagati in 1930. The magazine gave top billing to her story “The Umkana Tree” on its July 1925 cover: “A Vivid New Novel by Cynthia Stockley” (Fig. 12.3).

Limitations of space preclude a detailed examination of Page and Stockley’s large œuvres, but a brief summary of three bestsellers, each of whose sales exceeded 200,000 copies, will serve to indicate the relevance of contemporary Rhodesian fiction for The Rose of Rhodesia.

A tearjerker with “advanced” moral themes, Page’s The Edge o’ Beyond (1908) concerns the very different fates of two Rhodesian settler women. Dinah Webberly, the main protagonist, is a confident and freethinking globetrotter who enjoys the flirtatious companionship of three cheery bachelors, one of whom she eventually marries. Her best friend, Joyce Oswald, is a timid country girl, who leaves her sanctimonious and overbearing husband after the death of their child and accompanies another man to England, where she enjoys a brief period of happiness before dying of heart failure. Despite its setting, and in stark contrast to the male-authored Rhodesian novels of this period, typically action-adventure tales such as Bertram Mitford’s John Ames, Native Commissioner: A Romance of the Matabele Rising (1900) or E. C. Rundle Woolcock’s In Rhodes’ Land: A Romance of the Veldt (1913), Page’s narrative is almost entirely devoid of Africans (here contemptuously referred to as “niggers”). Instead, she focuses exclusively on settler relations: emotional solidarity among women; and romance between the sexes. Far from being an imperial arcadia, however, her Rhodesia is a place of physical, economic, and, above all, psychological hardship whose primary function is to put modern gender identities to the test. What draws Dinah back—“the free, untramelled vigorous life … the monotony and sameness” (Page 1917, 218)—is ultimately what drives Joyce to leave. Underpinning it all is a quintessentially colonial conception of class. Although Dinah, Joyce, and Joyce’s husband Oswald are presented, rather ludicrously, as having descended from aristocracy, Dinah reproaches Oswald in the novel’s climactic scene with having wrecked his marriage through arrogant conviction of his own superiority. In the new world of social mobility that is white Rhodesia, pedigree counts for less than character.

A different permutation of the same elements underpins the narrative arc of Stockley’s Poppy: The Story of a South African Girl (1910). Poppy Destin, an impoverished orphan, is rescued and educated by a man named Luce Abinger, who tricks her into a loveless marriage. Walking in the garden one night while Abinger is away, Poppy is seduced by Lord Carson, a charismatic financial magnate partly modelled on Rhodes. A feverish delirium prevents Carson from remembering the encounter, and Poppy goes alone to London, where her baby dies. Returning to South Africa as a successful writer, she reunites with Carson, who forces Abinger to grant her a divorce. The novel ends with Poppy, now Lady Carson, leaving for Borapota, “the latest possession of the Empire” (Stockley 1912, 447), of which her husband has been appointed administrator. As Anthony Chennells notes, Stockley’s conclusion echoes the “imperial fairy tale” format of Rhodesian romances by men (Chennells 2004, 77). Yet the narrative presents Rhodesia less as a topographical or political entity than as a place for resolving insurmountable contradictions, a moral corollary to the utopian vision in Page’s The Veldt Trail (1919) of “a progressive, enlightened country, with no slums at all, and no unemployed” (Page 1923, 206).

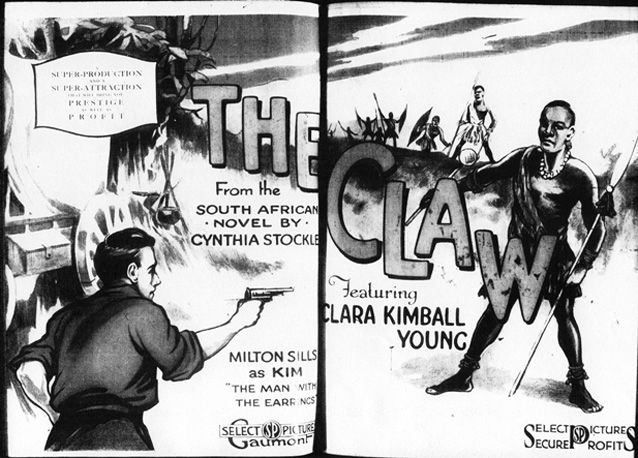

Our third example, Stockley’s The Claw: A Story of South Africa (1911), opens with Deidre Saurin, an Irish-American debutante whom bank failure has transformed into “an ordinary girl with a few hundreds a year”, travelling to see her brother Dick in Mashonaland. Raised to consider the world “as free to women as to men” (Stockley 1911, 12), she is a model of feminine independence: “I had a small but business-like Colt slung conspicuously from my waist-belt, and … [owned] three rather nice silver cups (probably all filled with late roses) awarded to me by various ladies’ shooting clubs” (Stockley 1911, 6). The novel’s central events—Deidre’s passion for a romantic adventurer named Anthony Kinsella, his disappearance, and her marriage to Maurice Stair, a Native Commissioner—take place during the 1893 Anglo-Ndebele War which led to the formation of Rhodesia. But national struggle is here little more than a backdrop for emotional drama: Deidre’s ostracizing by other settler women; her grief at Dick’s death; her marriage to an alcoholic who seeks to force himself upon her; and her thoughts of suicide. Female readers would have found plenty to identify with in this epic of colonial domesticity, as when Deidre laments: “I found, as many a weary woman has found before me, that housekeeping is the most thankless, heart-breaking, soul-racking business in the world to those who have not been trained to it from their youth upwards” (Stockley 1911, 385). Just as her petty trials are a microcosm of the convulsions of the fledgling colony, so, too, is Deidre’s personal redemption integrated into a broader narrative of Rhodesian statehood. Kinsella, it transpires, has been secretly kept a prisoner in the Matopos Hills by the famous oracle Ulimo,[2] whence he is rescued by the newly reformed Stair, at whose deathbed Deidre and Kinsella are finally reunited.

These Rhodesian novels present a number of obvious parallels with the Rose Randall storyline in The Rose of Rhodesia. Each centres on a romance between white settlers in which colonial conflict provides the setting for a journey towards personal fulfillment (and, on occasion, tragedy) for women who, in the words of Stockley’s “Dr. Jim” Jameson in The Claw, “have not disdained to come up here and feel the rough edge of life” (Stockley 1911, 167). Each features an independent and self-consciously modern heroine who unsparingly documents the hazards of veldt life for white women: unhappy marriages; authoritarian or self-obsessed husbands; the loss of children to illness; and the spectres of violence, adultery, war, and death.[3] (Although Rose avoids these perils by marrying Jack, her moment of choice is staged in a visual tableau [Fig. 12.4] that offers a glimpse of the marital discord—a central theme of Page’s The Veldt Trail and Stockley’s Ponjola—which could so easily have been her fate.) Each features, too, a preoccupation with class and, in particular, aristocracy, which is redefined as “character” in a way that recalls both the cynical recognition of African titular heads by imperial administrators and the peculiar snobbery of white Rhodesians. “‘It isn’t perhaps exactly what one would choose,’” declares a character in The Edge o’ Beyond brightly, “‘but it’s a lot better than being only a number in some suburban road of jerry-built villas, isn’t it?’” (Page 1917, 103).

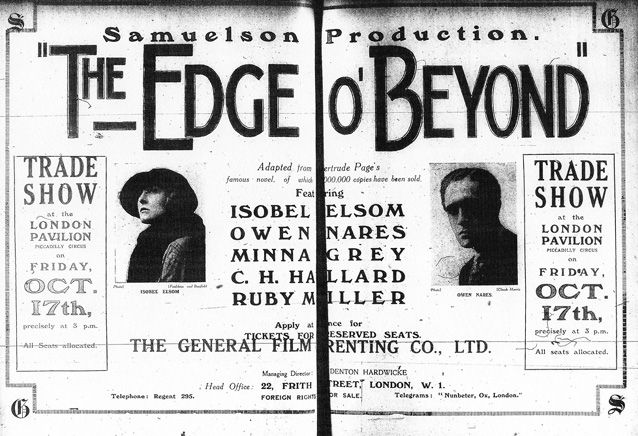

The most immediate connection, however, is that film versions of all three—The Edge o’ Beyond (dir. Fred W. Durrant, 1919) (Fig. 12.5); Poppy (dir. Edward José, 1917); and The Claw (dir. Robert G. Vignola, 1918) (Fig. 12.6)—were being shown in British cinemas the same year as The Rose of Rhodesia premiered in Britain.[4] Clearly, Hollywood was moving fast to capitalize on the Rhodesian vogue. An adaptation of Page’s Love in the Wilderness (dir. Alexander Butler, 1920) was followed by a string of films based on Stockley’s novels: The Sins of Roseanne (dir. Tom Forman, 1920); April Folly (dir. Robert Z. Leonard, 1920); Wild Honey (dir. Wesley Ruggles, 1922); Pink Gods (dir. Penrhyn Stanlaws, 1922); Ponjola (dir. Donald Crisp, 1923); The Female (dir. Sam Wood, 1924); and a remake of The Claw (dir. Sidney Olcott, 1927).

These were not the only cinematic treatments of Rhodesia, nor even the only Rhodesian literary adaptations. The Bioscope’s review of The Rose of Rhodesia on 6 November 1919 appeared in the same issue as a full-page advertisement for Allan Quatermain (dir. Horace Lisle Lucoque, 1919), H. Rider Haggard’s 1887 adventure tale set in pre-colonial Zimbabwe. John Buchan’s Prester John (1910), the story of a colonial uprising that spreads north of the Limpopo River, was also released as a film the following year. In 1920, a film version of George Cossins’s Isban-Israel (1896) was shot at the historic ruins of Great Zimbabwe, and by 1925 Haggard’s She(1887), a novel whose action also takes place in a setting strongly reminiscent of Great Zimbabwe, had been adapted for the screen no less than five times (Gutsche, 320n; Cameron, 17-23). Yet these grand epics, with their simplistic morality, occult villains, stage battles, and Boy Scout fascination with the practicalities of bushranging, could hardly be more different to the modern, metropolitan sensibility of Page and Stockley’s works. The prominence of illegitimacy, adultery, and predatory male sexuality in the 1917 film version of Poppy prompted The Moving Picture World to complain of an “unwholesomeness of atmosphere” and “questionable moral tone” (MacDonald 1917), and even Photoplay’s more generous reviewer noted that “like the Cynthia Stockley novel from which it was adapted, it has an unwonted freedom from the conventional manner of narration” (Johnson 1917).

As the title of Page’s Far from the Limelight (1918) suggests, early-twentieth-century Rhodesian novelists typically presented the colony as alien and obscure. Paradoxically, their very success meant that almost the reverse was true. By the time The Rose of Rhodesia premiered in Britain, a reviewer for The Kinematograph Weekly could remark that “much of the [film’s] grand scenery (crags, precipices and waterfalls) is of a kind which could only be taken in Rhodesia” (6 November 1919, 115). It is an amusing solecism, of course, since the film was shot in South Africa. But what stands out is the confidence with which the reviewer claims to recognize Rhodesia, and declares its “grand scenery” (an allusion, perhaps, to the fabled Matopos Hills) to be unlike any other. The previous week, a reviewer for The Bioscope had made a similarly telling remark while noting that an adaptation of The Edge o’ Beyond promised to do record business: “It was a matter of much comment when it became known that all of the ‘Rhodesian’ scenes [in The Edge o’ Beyond] were taken in England, which fact speaks well for British production” (30 October 1919, 54). In other words—and to use the jargon of marketing—The Rose of Rhodesia scored a coup by means of its unique selling point: convincing visualization of a “Rhodesian” landscape with which contemporary readers were already familiar.

Active Readers

Let us return to The Rose of Rhodesia’s own bookworm. At first glance, it is not obvious how Rose’s hackneyed feuilleton relates to the psychological dramas of Page and Stockley. Matters become clearer when we consider what kind of reader Rose is.

Rose reads on camera on five occasions. On the first of these, she stands outside her home and tends the white rose planted in memory of her mother. After reading about Cholmondeley’s departure from England (Intertitle 45), she looks up and shakes her head in a gesture of disapproval. On the second, she sits at a table looking despairingly at two coins before eagerly taking up the magazine. After reading about Cholmondeley’s arrival at the Rhodesian hotel (Intertitle 54), she looks up and smiles before checking herself, frowning, and looking off-screen. The film cuts to the rowdy bar in Green Willow, then back to Rose, who eventually falls asleep over the magazine. On the third occasion, Rose settles down with the magazine after Winters and her father have left for the mine. After reading about Cholmondeley’s enthusiasm for springbok steak (Intertitle 64), she grimaces in puzzlement and puts down the magazine in order to investigate the contents of her own cupboard. On the fourth, Rose has been indulging in some after-dinner flirtation with Winters. After Winters leaves the room, Rose reads about Betty’s reckless loss of chastity (Intertitles 81-82), which elicits from her a thoughtful look and a slow nod. When Winters returns in hopes of a kiss, Rose fends him off determinedly while the magazine lies on the table between them; he walks away, and she casts a glance after him before slowly picking it up. On the final occasion, Rose reads while awaiting her father’s return from a two-day drinking binge. Forlornly gazing off-screen, she bursts into tears and lowers her head onto the open magazine in front of her.

However we choose to interpret the facial expressions and gestures of what The Bioscope called “a well-known British Film Actress” (23 October 1919, 21), Edna Flugrath is unquestionably presenting Rose as an active reader. Rose reads the magazine story in terms of her own situation, the libidinal pleasures of escapism apparently co-existing with more didactic and emancipatory functions. She shakes her head in disapproval less at Cholmondeley’s predicament than at what it signifies: actual misbehaviour towards women. In turn, Seijaduntella’s fictional hotel leads her thoughts to the real one nearby in which her father is boozing. And Betty’s abandonment by her aristocratic seducer reminds Rose of the need to protect her own virtue and, with it, her value in the marriage market. Even though she is reading a mass-produced fantasy, her perspective is thus closer to the healthy scepticism of Page and Stockley’s heroines—“‘Some stupid novelist has been writing the usual twaddle about [Rhodesia’s] impossible Lotharios, and sunshine and flowers,’” snorts a character in Page’s Where the Strange Roads Go Down (Page 1913, 17)—than to Betty’s pathetic naivety. In other words, Rose is precisely the levelheaded veldt heroine that Betty is not.

This nuance was lost on The Kinematograph Weekly’s reviewer: “Edna Flugrath gives an interesting study of a girl naturally sensible, but imbued with the nonsense of a novelette, which she reads to counteract the melancholy caused by her loneliness, her father’s drunkenness and his failure. She is particularly good in her youthful coquetry towards the thief when she takes him to be a novelette hero” (6 November 1919, 116). Both assumptions in this statement—that Rose actually believes Winters to be Lord Cholmondeley (rather than just another mysterious stranger), and that the magazine story is primarily a device to justify her attraction to him—reveal an important blind-spot in how the reviewer sees women readers. By implying that there is necessarily a contradiction between “a girl naturally sensible” and “the nonsense of a novelette” (literally, sense versus nonsense), the reviewer passes negative judgement on all female readers of popular fiction.

This clichéd view of women readers as unsophisticated and uncritical, a view directly contradicted by the popularity of Page and Stockley’s writings, finds little support in The Rose of Rhodesia. For The Kinematograph Weekly’s reviewer, Rose fails to see through the dastardly Winters because trashy romance has muddled her thinking. In fact, she is quite capable of reading on more than one level. She empathizes with Betty at the same time as extracting the moral of the story, and delights in Cholmondeley’s exploits without ever forgetting that he is a literary cliché; when the nobleman’s steed covers two hundred miles in a single day, Rose rolls her eyes ironically and quips: “What a hard-working mule!” (Intertitle 56). She is no less adept in the realm of symbol and performance. First seen while tending her mother’s memorial rose bush, she presents Mofti with a bloom in token of his friendship with Jack (metonymic, in turn, of broader racial harmony), and, after Mofti’s death, she helps the Morels to plant a cutting from the original rose bush on his grave. The only plausible meaning of the question she asks when Winters arrives, “Could this be Lord Cholmondeley?” (Intertitle 62), is thus “Could this be my Lord Cholmondeley?”

This is a crucial issue because The Rose of Rhodesia encourages viewers to identify with Rose as a reader. All of the scenes of reading in the film take the form of an intimate, shared moment in which she sits or stands alone facing the camera while the audience is presented with her perspective by means of point-of-view shots of an alarm clock and what are essentially close-ups of magazine pages. But while Rose occupies a position analogous to that of the film’s first female viewers, two very different moments in the film make clear that neither she nor her audience are in any danger of conflating reality with fantasy, whether that fantasy be (as with Rose) marrying a baron, or (as with the film’s viewers) acquiring a fist-sized diamond.

After reading about Cholmondeley’s enthusiasm for fresh game (Intertitle 64), Rose picks up a tin marked “Fray Bentos Corned Beef” and a bunch of onions (Fig. 12.7). She pauses, shakes her head, and puts them back, then loads a rifle and goes out to shoot a springbok. When the men return home, she asks Winters which he would like for dinner. His choice of springbok apparently surprises and flatters Rose, who makes a show of casting aside the rejected item. Given the unlikelihood that the Liebig Extract of Meat Company paid Harold Shaw to promote their product so ineptly, the presence of a major brand in this context would seem to be incidental, merely a visual shorthand for tinned beef. Yet the name connects Rose with contemporary female viewers. Like Liebig’s meat concentrate Oxo and its rival Bovril, Fray Bentos was advertised heavily at the start of the twentieth century, particularly in magazines, and was rationed to civilians as well as soldiers during the First World War.[5] Those in the first audiences of The Rose of Rhodesia who shopped for food would have known it well.

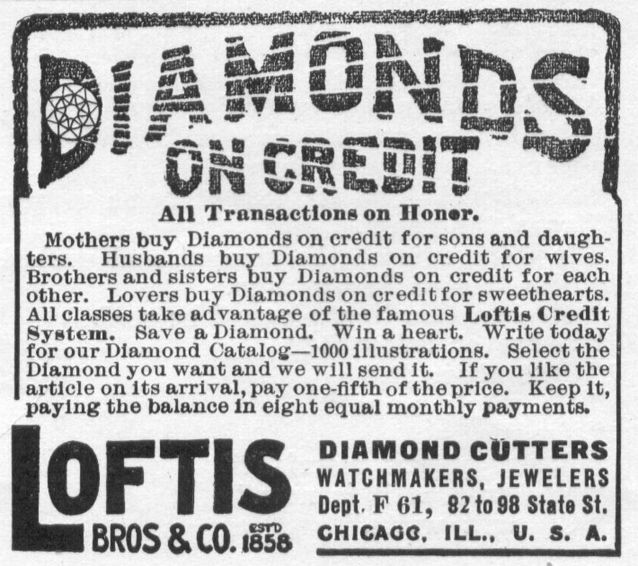

The Fray Bentos tin is less an endorsement of bully beef than a reference point shared by the new class of consumers which mass-circulation periodicals were helping to bring into existence at this time (Ohmann 1992). (In its very plot premise, that it takes a diamond to bring hero and heroine together, The Rose of Rhodesia echoes another recent consumer vogue: the diamond engagement ring [Fig. 12.8].) Popular fiction played a key role in this epochal development, not only providing content for advertising-driven publications but assiduously supplying this new class with a self-image founded on qualities of good sense, thrift, discernment, and, above all, independence. To this end, as advertisers quickly grasped, the image of the “outdoor” woman (Fig. 12.9) could be a powerful inducement, even for readers who would likely never go hunting—not unlike the way in which reading about aristocratic preferences influences penniless Rose’s own decisions. Whether or not the scene was devised as a product placement, audiences would have recognized in Rose’s wifely question, “Would you like tinned food or springbok?” (Intertitle 77), the well-informed female consumer whom magazine culture was helping to create. Fittingly, Rose’s identity as an object of identification for women viewers is itself replicated in the image of a smiling young woman that is just discernible beside the cocoa advertisement on the cover of her magazine (Fig. 12.10).

This dynamic also informs The Rose of Rhodesia’s closing vignette. Our principals, now happily married, struggle to cope with their four young children; Jack writes a sermon while Rose, rolling her eyes comically, tries to sooth a trio of wailing infants. The popularity of babies with cinema audiences, which dates from the Lumières’ Baby’s Breakfast (1895) and James White and William Heise’s A Morning Bath (1896), may have been a factor in The Kinematograph Weekly’s approving verdict: “This unconventional epilogue is a daring but welcome piece of realism” (6 November 1919, 116). But how, or rather, for whom, is this anomalous moment realistic? Not for us, certainly. The Karoo Diamond Mines Syndicate has given Rose a colossal reward—ten thousand pounds then would be worth almost half a million pounds today—with which she can hire an army of child-minders. By contrast, the scene would have struck a chord with many female moviegoers, whom cinema-owners were now courting with specially tailored enticements such as childcare services and baby contests (Stamp 2000, 22-3). In Rose’s situation as an overworked housewife, The Rose of Rhodesia presented the doubly appealing prospect of heroic motherhood in a domesticated colonial space to the early-twentieth-century female audiences so memorably evoked by Dorothy Richardson:

Tired women, their faces sheened with toil, and small children, penned in the semi-darkness and foul air on a sunny afternoon. There was almost no talk. Many of the women sat alone, figures of weariness at rest. Watching these I took comfort. At last the world of entertainment had provided, for a few pence, tea thrown in, sanctuary for mothers, an escape from the everlasting qui vive into eternity on a Monday afternoon. (quoted in Gledhill, 171)

Conclusion

Rose Randall and her magazine story thus connect The Rose of Rhodesia to a variety of significant contexts—literary, cinematic, and social. Foremost among these is the Rhodesian veldt melodrama, a subgenre of colonial writing which successfully grafted social commentary onto a conventional romance format. For all its recycling of stock elements from masculine genres, such as the imperial adventure (native uprisings, prophetic witch-doctors, heroic missionaries) and the crime thriller (stolen gemstones, white-collar villains, detective “specials”), The Rose of Rhodesia fully delivers on its title’s promise to relate the story of a woman’s experience.

The ideological contradictions of the film’s gender perspective—guns and roses, so to speak—are nowhere more apparent than when Rose goes hunting. To be sure, the prospect of Rose wielding a rifle recalls the militant iconography of the Suffragette movement, women’s involvement in the wartime munitions industries (itself a catalyst of franchise legislation in Britain and the United States after 1918), and, not least, the technological savvy that characterizes screen heroines of the silent era. This favourable impression of the safari as a space in which the sexes can meet as equals is seemingly further confirmed by Rose’s encounter with Mofti and Jack. But, in truth, this is a carefully staged performance of female independence: Rose is not so much hunting as shopping. Where the men engage in sport and homosocial bonding, her excursion is wholly subordinate to male desires; she leaves the house with the aim of pleasing one suitor, only to return after having roused the interest of another. As Mofti’s knowing allusion to the dangers of “wild animals like these” (Intertitle 67) confirms, the hunt’s real prize is not springbok but Rose herself, whom the film will ultimately reconfine to the domestic sphere as dutiful wife and mother.

Even so, The Rose of Rhodesia illustrates how women had become a highly desirable demographic for film studios and exhibitors by the late 1910s, a trend registered by all aspects of film production: a proliferation of female-interest storylines centred on physically capable and daredevil heroines; a transformation of actresses into “stars”; and an array of peripheral initiatives, including screenwriting correspondence courses and pseudo-democratic appeals to the “box-office plebiscite,” all aimed at fostering a sense of inclusion among women audiences (see Bean; Stamp, 120-1; and Morey, 1-34). Magazines like Rose’s were vital to this strategy. Their serials provided narrative material for film adaptations, which were then re-promoted by the same magazines in the form of “moving picture news” and publicity notices. Film exhibitors projected slides advertising the magazine provenance of their features: “This Theatre Shows Paramount Pictures. The photoplays you are reading about in the Ladies’ Home Journal, Saturday Evening Post, Woman’s Home Companion, Ladies’ World, American Sunday Magazine, and the leading magazines everywhere” (quoted in Stamp 2000, 23). And film studios used special supplements, prize competitions, and tie-ins to secure the attention of female readers of magazines and syndicated newspapers. Viewed in this light, The Rose of Rhodesia’s simulated magazine pages can be thought of as a cinematic counterpart to the film stills which had recently begun appearing on the pages of women’s magazines. As such, they reconfirm the significance of this ostensibly slight film as a document of cinema’s part in the formation of modern gender identity.

Illustrations

Fig 12.5. Advertisement. The Kinematograph Weekly, 23 October 1919, 11.

Fig 12.6. Advertisement. The Bioscope, 13 March 1919, 12.

Fig 12.8. Advertisement. Harper’s Weekly Magazine, 17 June 1905, 884.

Fig 12.9. Advertisement. Harper’s Monthly Magazine, September 1910, n.p.

Works Cited

Authorship: A Guide to Literary Technique. London: Leonard Parsons, 1922.

Bean, Jennifer M. 2001. “Technologies of Early Stardom and the Extraordinary Body.” Camera Obscura 16, no. 3: 8–57.

The Bioscope (London).

Cameron, Kenneth M. 1994. Africa on Film: Beyond Black and White. New York: Continuum.

Chennells, Anthony. 2004. “The Mimic Women: Early Women Novelists and White South African Nationalisms.” Historia 49, no. 1: 71–88.

———. 2007. “‘Where to Touch Them?’: Representing the Ndebele in Rhodesian Fiction.” Historia 52, no. 1: 69–97.

Donovan, Stephen. 2007. “Their Place in the Sun: Rhodesia and Women Readers.” English Studies in Africa 50, no. 1: 41–56.

Gledhill, Christine. 2003. Reframing British Cinema 1918-1928: Between Restraint and Passion. London: British Film Institute.

Gutsche, Thelma. 1972. The History and Social Significance of Motion Pictures in South Africa, 1895-1940. Cape Town: Timmins.

Hansen, Miriam. 1991. “Pleasure, Ambivalence, Identification: Valentino and Female Spectatorship.” In Stardom: Industry of Desire, ed. Christine Gledhill, 259–82. London: Routledge. First published in 1986.

Harper’s Monthly Magazine (New York).

Harper’s Weekly Magazine (New York).

Johnson, Julian. 1917. “The Shadow Stage.” http://www.stanford.edu/~gdegroat/NT/oldreviews/poppy.htm(accessed 10 January 2009). First published in Photoplay (August 1917).

The Kinematograph Weekly (London).

McCulloch, Jock. 2000. Black Peril, White Virtue: Sexual Crime in Southern Rhodesia, 1902-1935. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

MacDonald, Margaret I. 1917. Poppy. http://www.stanford.edu/~gdegroat/NT/oldreviews/poppy.htm (accessed 10 January 2009). First published in (The Moving Picture World, 9 June 1917).

Morey, Anne. 2003. Hollywood Outsiders: The Adaptation of the Film Industry, 1913-1934. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ohmann, Richard. Selling Culture: Selling Culture: Magazines, Markets, and Class at the Turn of the Century. London: Verso.

Page, Gertrude. 1905. “Second Impressions of Rhodesian Farm Life.” Empire Review 10, no. 56: 136–46.

———. 1913. Where the Strange Roads Go Down. London: Hurst and Blackett.

———. 1917. The Edge o’ Beyond. London: Hurst and Blackett. First published in 1908.

———. 1923. The Veldt Trail. London: Cassell and Company. First published in 1919.

“Poppy.” Variety, 8 June 1917, http://www.stanford.edu/~gdegroat/NT/oldreviews/poppy.htm (accessed 10 January 2009).

Stage and Cinema (Johannesburg).

Stamp, Shelley. 2000. Movie-Struck Girls: Women and Motion Picture Culture after the Nickelodeon. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stockley, Cynthia. 1911. The Claw: A Story of South Africa. New York: Putnam’s Sons.

———. 1912. Poppy: The Story of A South African Girl. New York: Burt. First published in 1910.

The Times (London).

Endnotes

[1] Index to The Girl’s Own Paper, http://www.mth.uea.ac.uk/~h720/GOP/ (accessed 10 January 2009).

[2] On the M’limo (Ulimo) as an anti-colonial icon, see Ashleigh Harris’s essay in this issue.

[3] For a thorough discussion of the situation for white women in Rhodesia during the British South Africa Company period, see McCulloch 2000, 85-108.

[4] See The Bioscope, 6 November 1919, 78; The Times, 3 November 1919, 10; The Bioscope, 13 March 1919, 12.

[5]

See http://www.tommyspackfillers.com/showitem.asp?itemRef=RL019 (accessed 10 January 2009).

Created on: Sunday, 16 August 2009