August 2014

Due to recent events in the Middle East, Screening The Past has decided to republish this interview with Vibeke Løkkenberg, director of Tears of Gaza. The interview was first published on the website of the Melbourne International Film Festival in 2011 pending the film’s screening at MIFF that same year.

The film was supported of the Norwegian Film Institute and was winner of the Audience Award at the 2010 Thessaloniki Documentary Festival and the Audience Prize for Best Film at the 2010 Göteborg International Film Festival.

“You can hold yourself back from the sufferings of the world, that is something you are free to do and it accords with your nature, but perhaps this very holding back is the one suffering you could avoid.”

– Franz Kafka

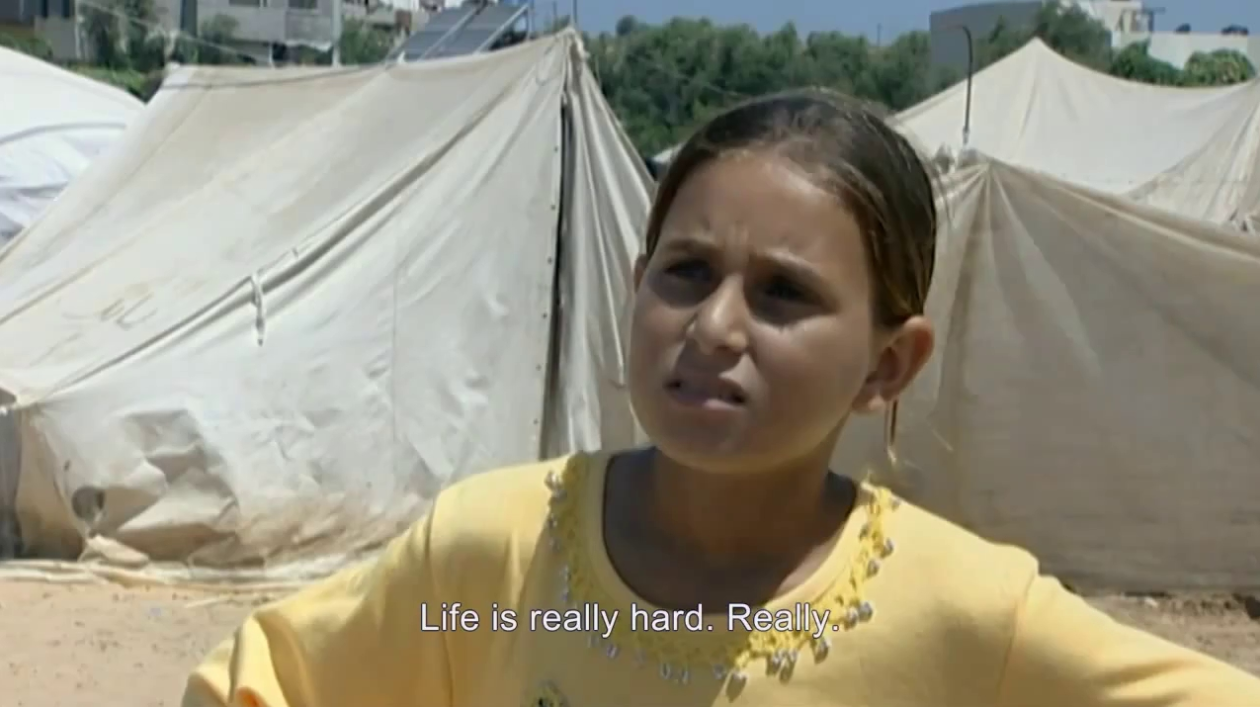

Tears of Gaza profiles three children—Yahya, Rasmia and Amira—in the aftermath of Israel’s bombing of Gaza from late 2008 to early 2009. Orphaned or left fatherless, the children exist hand-to-mouth, living in tents or among the ruins of their one-time sturdy homes.

But this documentary by Norwegian filmmaker Vibeke Løkkenberg is more than an observational film of how people, especially children, survive the experience of war. Wedded to the profiles is devastating footage of the actual military strikes, depicting scenes that are indescribably gruesome and emotionally disturbing to watch. It becomes abundantly apparent that at the heart of Løkkenberg’s film is the idea that we cannot and should not turn a blind eye to the atrocities humans have performed and continue to perform on other humans.

Tears of Gaza is a wake up call, a powerful anti-war documentary that challenges us to bear witness to the reality of modern day warfare. To paraphrase Susan Sontag from her book Regarding the Pain of Others, if we are surprised by what humans are capable of inflicting on others, then we have not reached moral or psychological adulthood, and that after a certain age we have no claim to ignorance, amnesia or innocence.

The virtue of Løkkenberg’s documentary (if indeed virtue is the right word here) is that it does not contain commentary on or any explanation whatsoever of Middle Eastern politics. Its only ‘voice’ comes from within Gaza, from those who were on the receiving end of Israel’s military strikes. There is no right or wrong in Tears of Gaza, only wrong. There are no justifiable victors, only victims. And there is no redemption, only suffering.

The following interview with Vibeke Løkkenberg was conducted via telephone and email in October 2010 and May 2011.

Raffaele Caputo

All that we see in Tears of Gaza can only have been experienced by those inside Gaza, and it is a very difficult film to watch, so my first question is whether the film we see is the film you as an outsider, a non-Palestinian, had originally intended? Or had you a different idea altogether?

No, I was very clear from the start that Tears of Gaza had to tell the story of three children who survived the attack [Israel’s bombing of Gaza in 2008 and 2009] and, as you know, my film has a lot of footage from the war that shows what those children experienced. Even though I was in Norway at a huge distance from the borders of Israel and Gaza, I was paralyzed and my eyes were transfixed to the television when I saw all those bombs dropping on Gaza. No media were allowed in there, they locked everybody out, but in keeping the rest of the world out I was also furious that they had locked people in.

Then right after the war I saw a Gazan boy interviewed on one of those short news segments we always see on television, but it could not describe what he had experienced in only a few minutes. When I saw that segment I can remember saying to myself, “I don’t know these people, I don’t know these children, but what is their suffering after they’ve lost fathers or mothers or maybe both? How do they live now? How do they manage to come through?” That was when my husband [Terje Kristiansen] and I decided to go over and make a movie. We went to Israel but we weren’t allowed into Gaza to make our documentary. We then tried to get in via Egypt and we tried `Ein Rafa many times, and again we could not get in to speak to those children.

But when I returned to Norway I was able to make contact with a Palestinian crew through my contacts in Norwegian television, and that crew was the same news crew that had interviewed the Gazan boy. Everything was done by phone and email, all the communications on how to make the film, the questions, and everything to do with the children.

So you did not actually step inside Gaza?

It was impossible; everybody was locked out! Only big television networks could go in, and only networks the Israeli authorities believed would give “balanced reportage”.

Tears of Gaza contains a lot of footage shot during the bombings and at sites of bombed buildings with very distressed people pulling dead children out of the rubble, or rushing loved ones to hospital, or trying to put out fires, and these are scenes of complete chaos. Was much of that footage shot by different people on small digital cameras or mobile phones? If so, how were you able to source such graphic footage and get it to Norway, especially given that you were not allowed into Gaza?

What I did first was to have others ask the children questions about things that I was curious to know about. Then I had to search for material to prove that what they said on camera was true. So when they talk about the UN-run school that was bombed, it was important for me to be able to show footage of when and where that happened.

Of course, because all of Europe was locked out by Israel just before the attack, I knew there had to be footage shot by Palestinians inside Gaza. You must remember that no journalists where allowed in, and the West will not accept footage shot by “Hamas”. Western journalists are not allowed to “trust” pictures made by supposed “terrorists”. There is censorship around the reporting of war across all television companies, instituted under the guise of protecting so-called ordinary people against seeing real images of war or of people being massacred. But we knew that people inside Gaza had to have taken this sort of footage and we sourced images with this exact subject. Obviously different people had shot different bits of footage, but I do not think any of those images were taken on an iPhone, for example. The footage used in the film was taken by professionals living in Gaza, who travel all over Gaza and record everything with their cameras. We secured agreements with them and paid for that material.

To get the footage out of Gaza was difficult and was very risky and I cannot tell you how we did. It was not done in the open and not through the post. We had helpers everywhere is all that I will say.

So your crew in Gaza was made up of the same people who shot footage of the bombings?

Yes, and you can tell from the film that the photographers were at risk and were themselves almost targets for the bombs. You can see how close they are to getting bombed—and their images are such that the West would never show on television.

How did you manage to direct the crew in Gaza while you were based in Norway? Did you gather as much footage as possible from them, chose what you wanted and then edited it together?

No, they were asked to follow my ideas when it came to the children. They had nothing to do with the editing, nothing to do with the project really except to film. We worked very closely even though it was over the Internet and by telephone, which meant I had to be very detailed in what I wanted them to film, and I also composed very specific questions for them to ask the children. If there was something I didn’t like, I would call up my contact and say, “You have to do it again, you have to try this or try that.”

I think directing the crew from afar worked very well in this case because I was not seen as a Western journalist who was being a nuisance in Gaza. The crew I had was not like having a bunch of Western journalists running around Gaza trying to get some news ‘grabs’. Palestinians don’t really like Westerners because the West doesn’t really understand and doesn’t really help. But the Gazans trusted my crew because they come from Gaza.

When watching Tears of Gaza I was very much reminded of how images that came out of the Vietnam War turned public opinion against that war.

Yes, many people have said that and that is my goal for this film. I hope it will bring about a movement, the same reaction that people had when they started to see pictures from Vietnam, like the one we always remember of the little naked Vietnamese girl running away from the napalm bombing. I’m glad you brought up this topic because the images of war that are often taken are those of soldiers in battle, injured or in body bags, but it was more the images of civilians and of children especially, that actually turned the tide against the Vietnam War.

In the Middle East right now there are so many weapons and so many bombs and they are always prepared for war. I think the only way to change people’s understanding of modern warfare is for them to see a war like the 2008 bombing of Gaza, because we are the ones who are hit, you and me, civilians, and the reason is because the intended targets are just not there!

One gets an understanding of why people when put through such suffering would want to retaliate in kind. But what is extraordinary about the three children is that they do not wish to retaliate with violence—one wants to become a doctor to help her people, another would like to be lawyer to fight in a different way…

That’s right, the children have understood that violence will not solve the conflict. They don’t want violence, they have experienced it, they still experience it, and they see no resolution coming from it. The children are completely pacifist, and this is also my conclusion because what the film says is that a political agreement cannot be reached through any war. When this is understood, nobody would want to drop anything on anybody else. Not even a stone. It’s very important for me that the people watching my film meet these children, have deep compassion for them, and that the conclusion is for the audience to fight in another way too.

For most of us in the West, what we are led to believe about Palestinians is that they are always throwing stones at the Israelis and that they are suicide bombers. These are the only images of Palestinians that come through television. But that is not the reality. There is another reality of these people trying to live everyday lives, trying to be happy, trying to solve their small problems, but which are actually often big problems like not having any water. Sometimes, Israel is seen to make life easier for the Palestinians, when they give them some cars for example. But a few cars do not drastically change their lives for the better, doesn’t change the basic occupation situation, and their homes will not be built again. Such gestures are a way of ‘faking’ the reality for the rest of the world, making it look as though life in Gaza is better than what it really is.

But I must emphasise that Tears of Gaza is not only a movie about Israel and Gaza; first and foremost, it is also an anti-war movie.

Is this why you chose not to provide any historical or political background or to explain anything at all about events leading up to the bombing of Gaza?

That’s right. This documentary gives another perspective on that conflict and it’s a perspective rarely seen. It’s from the point-of-view of the victim. The victims are the only people who interest me. I am on the side of the victims because my documentary puts you, the audience, down on the street to feel what it is like to have bombs rain down on you. I was not interested in the political situation because there are so many documentaries and so much news reportage that already provides that type of analysis. Tears of Gaza was never intended to be that type of documentary.

I think it’s distressing the way the film begins in the present day with a moment that shows a wedding, and one thinks that life isn’t all that bad in Gaza, that there is still hope and life continues, but we also notice the child who sometimes looks up at the sky, and then the film cuts to footage of an explosion in 2008. For the viewer, suddenly that sense of hope is completely shattered and the momentary sense of security is absolutely false and you realise that these people live under constant threat of being killed.

Yes, these people have to live with these drones all day and all night. Do you know about the drones? They are used in Afghanistan, they are used in Iraq, they are everywhere. Among all of the material that I obtained for this film, there was footage that showed a group of friends and one girl was picked out and she was completely destroyed in under a second. These drones can see your shoes and can pick out all the buttons on your clothes. They are so precise in killing that everybody constantly lives under stress. Everyday someone is shot there. But the world doesn’t react anymore because we are getting used to this occupation, getting used to this problem, and we are getting used to wars in the Middle East.

You were not allowed into Gaza, how different do you think Tears of Gaza would be had you been allowed to enter?

We tried three times to enter. We even thought of taking a chance at entering through a tunnel, but on the day we arrived the tunnel had been bombed. As I said before, I think Tears of Gaza maybe would have suffered from me being there because I would have been seen as a journalist. I am a Western woman and they are annoyed at the West because we have not done much to help and especially not children. I think the best thing was that a Palestinian woman was able to relay my questions to the children in their own language.

Besides, journalists are only allowed into Gaza for two or three days at a time, and for me to be in Gaza as a Western woman would have been more limiting. Whereas with the Gazan crew the camera was able to follow the children over a long period of time, so it was maybe a good thing that I was not allowed in.

Are you in touch with the children now?

There is no way. I cannot get into Gaza to see them. The only one I spoke to face to face was the girl who appears late in the movie because she came to Norway for treatment on her leg. It took six months before she could come out and I was able to talk to her in person. But for the other two children I have had no direct contact. I know that the crew is still in the contact with all of them, but I am not. I cannot even send an email because the children don’t speak any English.

Tears of Gaza does not offer a solution to the conflict, but that is not to say that your film does not have a role in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I think, importantly, your film’s role is first to bear witness to the suffering that humans can do to others. Only then can people move to a solution because, as the boy says in the film, “They can give us the world, everything, but we will not forget”, which is not to say that they cannot forgive. Would you agree?

No one can ever forget what they experienced during a war such as you see in Tears of Gaza. Those children are forever traumatised. Then there is the father of the little girl with phosphorous burns all over her face, and as he says, “How can I ever forgive people who kill innocent children?” So, really, I don’t know.

A recent visitor to Australia was Izzeldin Abuelaish, a Palestinian physician who has cared for both Palestinian and Israeli patients and who wrote the book I Shall Not Hate [Random House, 2010] about having lost three daughters in the 2008 bombing of Gaza. Abeulaish claims that traditionally, historically it is men who wage wars and women who make peace. Do you think Tears of Gaza is a film that only a woman could make?

I do not know if this film could have been made by a man. I certainly felt like a mother more than a director when my instincts told me to just go for it, to go for these children and to bring their story to the rest of the world, to pass through the wall that Israel has literally placed between us to keep us apart. For me, it is important to shake up people’s minds and make them see that these children are our children, that the “them” is “us”, and that it is not a “he” or “she” but a “me” who is being bombed. I think it is only through expressing true emotions that you can identify and reach empathy with victims. Not by “balanced” reportage led by Western commentary, with annoying voices making political analyses. There is no voiceover in this film, nor any theory or explanation, only an attempt to show you the suffering of others, as you would suffer in the same situation.

I hope this film can do the same for peace as did the photo of the little Vietnamese girl. This is why I am glad I didn’t go into Gaza, because I think I would have been distracted by a city in ruins, but I didn’t need the whole city for what I wanted to do. The children’s faces became my Gaza. When they told their stories and tears began to roll down their faces, for me that was the real Gaza.

Raffaele Caputo is co-editor of Screening The Past (www.screeningthepast.com/).

A special thank you to Lisa Gerrard for making this interview possible. Thanks also to Alice Garner and Alice Pung for their input.