| George Kouvaros, The Old Greeks: Photography, Cinema, Migration. UWA Publishing, 2018. ISBN: 9781742589923 AU$24.99 (pb) 208pp (Review copy supplied by UWA publishing) |

|

“To grasp the people and places to which we are closest as no more essential or permanent than the memories that pass in and out of our consciousness: this is our feeling of displacement that defines the story of migration told in this book. The films and photographs that I discuss provide a platform from which to grasp this feeling.” (Kouvaros, p. 19)

The Old Greeks: Photography, Cinema, Migration by George Kouvaros is a deeply personal and moving book that combines memoir and family history with the critical, cultural and formal analysis of still and moving images. It is a book in which Kouvaros, who arrived in Australia from Cyprus in 1966, tells stories of his own, and his extended family’s, experience of migration. It is also a scholarly study in which Kouvaros examines some of the ways that photography and cinema provided a map for the migrant experience, laying “the ground for how the journey was conceived and served as practical tools for dealing with its consequences” (P. 12)

This book brings together several strands of Kouvaros’ research and writing. He has written a number of important books and essays that examine the work of artists as diverse as Paul Schrader, John Cassavetes, Wim Wenders and Robert Frank. He has shown particular interest in work that takes place at the nexus of cinema, photography and performance. For example, in the book Famous Faces Not Yet Themselves: The Misfits and Icons of Postwar America (2010) he looked at the work of the Magnum photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Eve Arnold that was taken on the set of The Misfits (Huston, 1961) exploring ideas about performance and film acting and shifting changes in the Hollywood studio system. In Awakening the Eye: Robert Frank’s American Cinema (2015) he examined Frank’s photography, films and videos and some of the ways in which Frank used these different media to find new forms of visual expression.

Kouvaros has also written extensively on the migrant experience with essays published in Life Writing, Southerly, Cultural Studies Review and Screening the Past. In an article in Neos Kosmos that discusses the book, he is quoted as explaining that, “The project began as a series of short essays and personal reflections which were motivated by the desire to try and make sense of the relationship of two worlds; one being my own family’s past and culture and the other being the world I found myself into, after leaving a volatile Cyprus to come to Australia.” [1]

A broad tapestry of theorists, artists, writers and thinkers including Nikos Papastergiadis, John Berger, Edward Said, Marcel Proust, Roland Barthes, Elizabeth Gertsakis, V.S.Naipaul, Walter Benjamin, Siegfried Kracauer, George Seferis and Italo Calvino, to name just a few, provide a critical, aesthetic and autobiographical framework for Kouvaros’ own intricately observed and poetically evoked migrant stories.

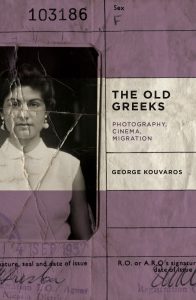

At the heart of this study is Kouvaros’ own mother. The book begins with his description of a Government of Cyprus identity card from 1957 that features a black and white photograph of his mother. This identity card is on the cover of the book, and this particular image of his mother frames and permeates the study in a number of ways. It is an affecting image, a record of a particular moment in her life, but it is also a document of a social world that was changing, a treasured fading document passed down to the next generation, as well as being a focus for many of the reflections and investigations that follow. Kouvaros’ engaged study of this image of his mother is an obvious reference to Roland Barthes’ reflections on the photographs of his own mother in his book Camera Lucida and Kouvaros thoughtfully follows on from Barthes’ questions about what a photograph can mean and the mnemonic power of simple snapshots.

Vernacular photography is central to Kouvaros’ observations about the experience and memory of migration. Most of the photographs that are discussed in the book, and a selection which are reproduced, are staged portraits or documents of family gatherings. Kouvaros makes the important point that there was a key historical convergence between the rise of postwar migration and the increasing availability of cameras, film stock and printing facilities. He writes that, “the process of postwar migration occurred at the same time as photography shifted from the domain of the dedicated hobbyist to a universally available medium for recording everyday life.” (P. 25) He describes the suitcases of departing migrants in which carefully chosen photographs were an essential part of the personal belongings that accompanied people on their journeys to new lands. He also discusses the way that these photographs from the homeland became part of a larger narrative, when photographs from the new life, documenting new places and commemorating various events and celebrations, were sent back home “inside airmail envelopes” (p.26), building an archive of image memories that formed ongoing connections between the past and the present.

While photographs provided a map, a toolbox, and a process of memorialization for the postwar immigrant, the cinema provided another kind of map. Kouvaros’ discussion of the connections between cinema and migration are interestingly diverse and intersect with his observations about photography. He describes how films were watched – in theatres as well as in church halls – as well as the kinds of films that were watched, and the various meanings drawn from, and attributed to, them. He explores an eclectic range of films with individual chapters on the independent films of the Greek-Australian filmmakers Anna Kannava and John Conomos, a chapter on the film about homecoming, Reconstruction (1970), by the arthouse Greek filmmaker Theo Angelopolous, and a chapter on the Hollywood film A Place in the Sun (Stevens, 1951).

Kouvaros says that when his mother talks about her past she talks about the influence that the cinema had on “her understanding of the world” and on her own transformation (p. 66), pointing to an important symbiosis between the cinema and personal growth. A key film for her is A Place in the Sun which stars Elizabeth Taylor as a beautiful socialite and Montgomery Clift as the ambitious assembly line worker George Eastman who falls in love with her but is also involved with another woman – a love triangle with tragic consequences for everyone. Kouvaros notes the way that his mother responded to the film through the lens of her own experiences. He says that when she talked about A Place in the Sun she did not see Clift as “the ambitious social climber that critics and reviewers describe” (p. 66-67) but instead she saw him as someone who was trying “to enter a world that is out of reach, someone confused, inhibited, inward; in short, a more complete embodiment of her own anxious, transforming self. “ (p. 66 – 67) Sixty years later, when the film is screened on television, she is not prepared to watch it again, suggesting that there is “some part of who she was then remains preserved in her memory of the film” (P.79), something that Kouvaros compares to the way that the faces and bodies of actors are also preserved in the celluloid of the film. This leads Kouvaros to the claim that, “A film about the failure of the American dream and the power of a grand romance is also a film about the feelings of homesickness brought on by migration.” (p. 80)

The two chapters on the films of Anna Kannava and John Conomos provide several key insights into the artistic practice of these two experimental filmmakers but focus, in particular, on their films about the migrant experience. Kouvaros finds echoes of his own memories of returning to his homeland in Kannava’s film Ten Years After….Ten Years Older (1986), and discusses a number of ways that the bridging of the past and the present of the migrant experience informs her film The Butler (1997). With his discussion of the multimedia work of Conomos, focusing in detail on the video Autumn Song (1996) and the video installation Album Leaves (1999), he finds the continuing connections between cinema, memory and reflections on migration.

The Old Greeks: Photography, Cinema, Migration includes a number of photographs but I would have loved to have seen more, which is further testament to Kouvaros’ evocative writing style, one that creates desire for the images that he describes. Perhaps there could be another project – an extended image archive of remembrance – that would be another kind of book? There was one photograph in this book that particularly moved me. It is the ‘lost photo’ of Kouvaros’ mother walking in the streets of downtown Johannesburg, wearing a striking checked coat, appearing to look at her own reflection in a shop window. It is a photo taken on the street by a photographer unknown to her who found her and gave it to her the following day. It reminded me of a photograph that I have of my mother, who was an immigrant recently arrived from Eastern Europe in the early 1950s, walking in a Melbourne city street, also captured by a street photographer. And that is one of the resonant gifts of this book, that it tells a personal story of migration and, in its telling, connects to other stories of migration that are part of the fabric of our culture. As Kouvaros himself says, “Details of our departures and arrivals are entirely our own, but they also link our history to the histories of others.” (p.108) This is one of many, very good reasons to read this book.

[1] Theodora Maios, ‘The Old Greeks’, a multimedia exploration of migration.” Neos Kosmos, 6 February, 2019

https://neoskosmos.com/en/128820/the-old-greeks-a-multi-media-exploration-of-migration/