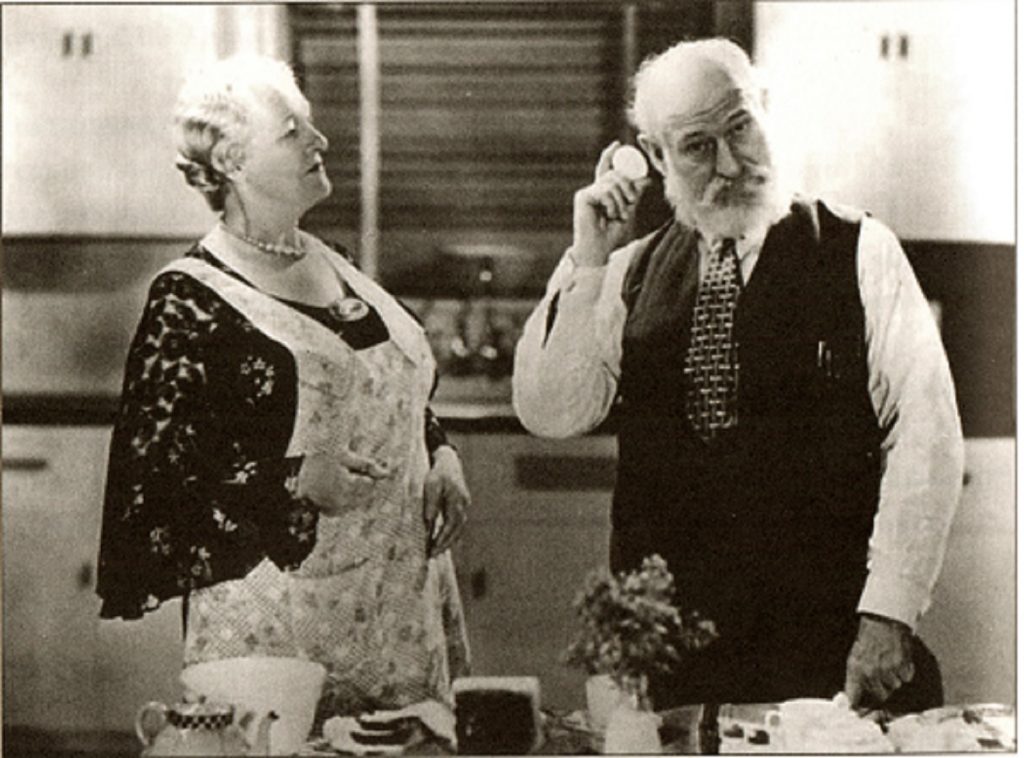

Production still from Dad And Dave Come To Town (Australia 1938). Dir. Ken Hall. Cast: Bert Bailey (Dad Rudd), Connie Martyn (Mum). [2]

The joke here is a sound joke. Moreover it is a sound joke which gains its punch from the silence in which it is made. The reader/viewer of this still hears nothing, imagines a tiny shifting noise, perhaps even a soft pecking. And the reader of this essay recognizes that sound is figured in the most silent of films, just as it figures in all performances of John Cage’s 4’33’’.

This is not a question of the absence of perceptible sound, but of the presence of sound in the mind, and particularly its presence provoked by visual images.

My gaze shifts from Dad’s listening, swiftly to Mum watching him, then back again and back, looping between a noiseless noise and a stern regard, between the ear and the eye. The image analyzes, deconstructs the situation it figures, perhaps even interprets it – the innocent, heedless listener; the judging, all-too-conscious watcher – reader/viewer and image/text. But it will not do to ignore what is so clearly figured, the clear sense of the image, what jumps out at you. We, the looking, are not so divided. We are what is looped, we are inter-sumus, in between: looker and looked, listener and listened. And all this simultaneously – all this and more – an impossible, mundane situation, probably mere existence.

This sense of the image jumps me back to a vague, terribly important, sense of the (sometimes inner) ear. What happens when I listen to what I am looking at? I think it is possible to listen to what you see; it happens all the time – we translate images into mental sounds. This is the usual way of sensing silent films. In Australia many of the earliest films were silent images of Indigenous Australians dancing, music made visible in the actions of the shadows on the screen. Today many such films are prohibited for public viewing because there are obviously ghosts on the screen. I know of no such prohibition against playing recordings of Indigenous music, although it may exist, but my belief is that the sense of music is life itself, and life is not usually prohibited.

Making Australian cinema

Position

(1994). . . beneath the ugly surface of what is shown to have happened to Aboriginal people, [The Last Wave, Australia 1977] goes to a lot of effort to reveal something which it, at least, would call fine and worthwhile. It says that the destruction of Aboriginal culture is a self-serving lie, that the culture is more powerful than the white man’s history and the white man’s photographs. This too, is a lie – but it is a noble lie. And it is the same lie we tell ourselves about ourselves.

And so The Last Wave shows apparently opposing ideas of `civilisation’ (or `history’) and `nature’ – and it shows one person, David, moving away from one and towards the other.

But David is, as we have seen, finding his identity. If he is moving away from civilisation and towards nature, it seems inescapable that his identity is to be found in nature. At one point he dreams that a young Aboriginal man is holding a stone out to him upon which a symbol of his, David’s, identity is painted. This man has the secret of his identity and is trying to give it to him.

. . . That is a pretty clear statement, I think. David is drawn away from his family and towards the Aboriginal people because his identity is somehow to be found with them or through them.

Now I have said that David is an Australian [like me]. Apparently, according to this film, an Australian finds identity with or through Aboriginal people. That sounds like a fairly radical political stance . . . [3] 3

Action

(2018) . . . or the premise of an essay on some of the ways hegemonic “white culture” has deployed Indigenous Australian imagery in early Australian cinema – as motion and sound, absence and presence, ghost and spirit, window and mirror. (my)self and (you)other. What might these images, these figures, make of us as we watch and listen to them?

As I work, I will be looking at and writing about certain films over and over, making detailed observations of precisely what is happening in the frame in order to construct detailed readings of what these films show. My intention is to draw viewers into recognising what these films “say” in a way that pays full and respectful attention to what is shown. That is, my work is not intended as anthropology or ethnomusicology; it is about what I/you can see and sense in the film itself – what the film makes of what it photographs. In this way perhaps I/you will figure ourselves closer to the “noble lie” of figuring an identity in sound and silent images of Indigenous Australian people.

“The Australian cinematograph” (1897) by Henry Lawson

Ina Bertrand makes a case for this story as a vision of the new technology, predicting the Australian cinema-to-be – not the fluttering black-and-white images that Lawson, a city-dweller, had already experienced but the full-blown cinematic experience of today. Lawson’s “Australian cinematograph” is, in effect, the first work of Australian cinema – and in that work an Indigenous Australian plays a pivotal role.[4]

A drover, accompanied by an Indigenous Australian “black boy”, is near death from the sun and thirst. The two make it to a waterhole that just might have some water, their last chance. The boy is sent inside with a quart-pot and a “tomahawk”.

The black boy kneels on the clay, sets the quart-pot down by his side, and raises the tomahawk. The pot, unevenly balanced on a curl of clay cake, falls in his way; he puts it aside with the quick monkeyish movement peculiar to lower races, lifts the tomahawk again and strikes deep. And the scene goes black out – a blackness like that which comes momentarily to eyes, blinded by perspiration, in a heat-wave in the drought.

In the drought-gloom a sound like the long low moan of a big mob perishing out on these roofs of hell – and the music, and, through it all, the words of Barcroft Boake’s song, now wailing, now fiercely triumphant:

“East and backward, pale faces turning –

That’s how the dead men lie!

Gaunt arms stretched with a voiceless yearning –

That’s how the dead men lie!

The “black boy” of a “lower race” substitutes (1) for the drover and (2) for the drover’s son, who waits at home, not knowing the truth of how his father died and how the black boy acted as the man and the man’s son. Indeed, the black boy is swallowed by blackness, totally effaced at the moment of his extraordinary deed. The text, the imagined film, Lawson, the Australian cinema-to-be, vanish him.

The Earliest Moving Images of Australian Indigenous People

Alfred Cort Hadden and Walter Baldwin Spencer, as well as others named and nameless who made the earliest Australian documentary films representing Australian Indigenous people have a great deal in common with Henry Lawson. Lawson, Hadden, Spencer and the overwhelming majority of the documentarists represent Indigenous Australians with sound images (dancing most obviously). A specific figure of ‘Aboriginality’ is constructed by these films, a kind of ‘savagery’ in which there is strong sexual imagery (women’s breasts and the genitals of men and children; the genitals of mature women are not shown), images of menace (spears pointed at the camera, etc.), physical disfigurement (body painting, tattooing, scarring – but also diseases of the eyes, missing teeth, etc.), and diet (snake, goanna, roots, etc.). The films are making savages of the people shown to us. Moreover, as they dance, show their bodies, act in menacing ways and eat food that white viewers find repugnant, they are clearly being told what to do, directed to act as ‘savages’, by a voice I/we cannot hear but which I/we know must be speaking to them/to us. That is, these films are far from being ‘documents’; they are cinematic fictions made by white Australian filmmakers for the consumption of white Australian audiences: they are the Australian cinema.

Alfred Cort Hadden

[Alfred Cort Haddon’s 1898] expedition, which lasted for seven months in 1898, broke new ground in almost every aspect of its work. [W.H.R.] Rivers pioneered the use of genealogy to elucidate social systems, ceremonies were reconstructed, informants were cross-checked, speech and songs were recorded on wax-cylinders, and Haddon made some of the earliest ethnographic films. The result was a rigorous and sophisticated regional ethnography, the bulk of which Haddon edited and published in six volumes between 1901 and 1935: Reports of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits. It remains the seminal work in Torres Strait studies.

[5]

Walter Baldwin Spencer

In 1901 [Baldwin] Spencer and [Frank] Gillen were sponsored by David Syme of The Age in a journey to research [the Aranda] tribes, taking with them a kinematograph and a phonograph recording apparatus. The trip was reported in scientific journals at the time . . . and some of the results of the research have survived for study by modern scholars. Spencer toured extensively with the films, lecturing as he presented the images, and replaying his phonographic records of tribal chants to accompany them. A second expedition in 1912 produced further material. [6]

Although a kindly humanitarian in practice, in theory he saw Aborigines simply as dehumanized ‘survivals’ from an early stage of social development. His voluminous written and photographic records endure as a priceless Aboriginal archive, despite his unacceptable value judgements on their fossilized society.

[7]

Here is a list of some of the tropes of ‘Aboriginality’ and ‘whiteness’ I have identified in the silent documentary films of the period which I have watched for this essay – in no particular order.

— Casual racism (“Black’s Camp”, “Aborigins”);

— Indigenous Australians fed, given gifts, herded, measured, lined up – made ‘civilized’ – by whites who stand in a small group to one side;

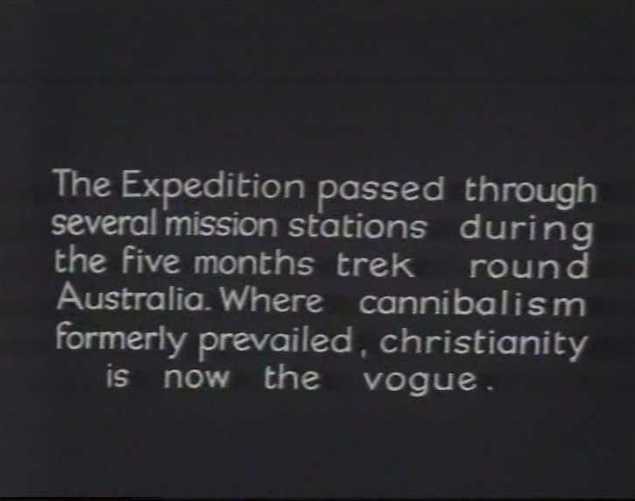

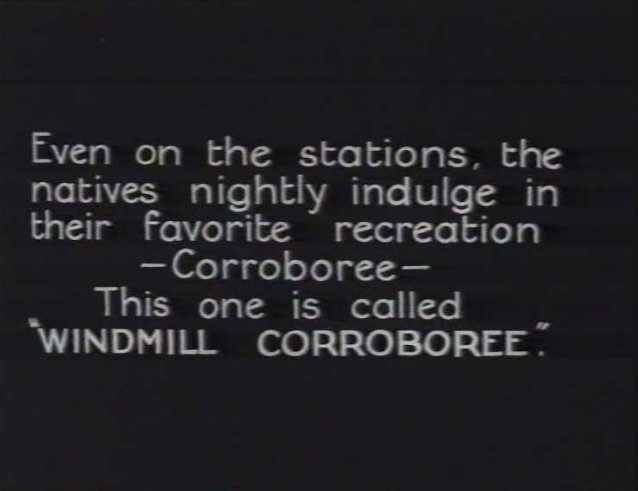

— Indigenous Australians doing ‘Aboriginal’ things: making fire, smoking pipes (a crying baby is given a smoking pipe in one ugly moment), talking in pidgin English in intertitles, dancing traditional tribal dances for “recreation” while they live otherwise ‘Christian’ lives

Here is a sequence of five titles ands images from a documentary produced by one ‘scientific’ expedition:

|

|

|

|

The Story Of The Kelly Gang

![]()

The image is a (fabricated?) “documentary” shot that holds non-fiction and fiction in suspension. Was it acquired by photographing indigenous trackers who happened to be in the vicinity? Was it perhaps a ringer, footage not shot by the Kelly Gang crew at all? Did the trackers know they were to appear in a film about the Kellys? In a fiction?

These questions suggest the level of exploitation which this simple and straightforward image displays and conceals at the same time. The white filmmakers are (ab)using their Indigenous subjects, making them objects, colonizing their images. It is as if, in this moment of photography, the Australian cinema had to display its Indigenous peoples, just as Lawson somehow had to display his “black boy” in his account of “The Australian Cinematograph” and Haddon, Spencer, and others had to display their various “savages” as they made their/our Australian cinema.

But The Story Of The Kelly Gang is also, is first of all, a fiction film. If there is an imperative within the Australian cinema to display its white filmmakers’ visions of “Aboriginality”, that imperative has shaped its fictions as much as, perhaps more than, its films of fact.

Australian fiction films 1906-1917

In these early years [Australian cinema] was essentially an indigenous cinema, reflecting the producers’ direct responses to the Australian audience, without reliance on established models from overseas. It was perhaps the most acutely ‘national’ period in Australian cinema, and many of the recurring themes and motifs of the local cinema were first explored and defined at this time . . .

. . . producers tended to favour subjects with open-air Australian settings – stories of the convict days or of the gold rushes, sporting dramas, tales of station life in the outback and, above all, bushranging adventures.

[8]

. . .

The production industry was . . . hampered by the banning of the bushranging genre by the New South Wales Police Department in 1912 . . . The ban remained in force until the 1940s and had a powerful influence on Australian popular culture . . .

[9]

The period from 1906 to 1918 was also the period of the first sustained work by most of the ‘pioneers’ of Australian silent cinema. Raymond Longford, Bert Bailey (actor and director), John Gavin, and Franklyn Barrett began their careers as filmmakers consciously ‘voicing’ Australia (for example in Longford’s 1913 Australia Calls). The “open air Australian settings” favoured by these filmmakers, and the genres which attracted audiences, had the effect of white-washing the screen; Indigenous Australians were replaced by ‘ordinary Australians’ or were made objects of amusement or fear. By 1918 it seemed that dancing, menacing, guzzling, smoking, slanging ockers had effectively wiped ‘Aboriginal’ savages off the screen, and had become Australia’s “enemy within”.

But that was not the case.

The Enemy Within

In The Enemy Within (1918) the hero’s sidekick, Jimmy Cook, is played by the then famous indigenous Australian boxer, Sandy McVea. Indeed it may well be that McVea was at the time at least as famous throughout Australia as the film’s ostensible star, Reg “Snowy” Baker.

Both men are charismatic and athletic but, to my eyes at least, McVea is made for the cinema, whereas Baker is merely a daring stuntman. McVea simply moves better, but his movement is not something that can be captured in a frame enlargement, so here is a production still which comes close.

At any rate, the Baker-McVea partnership did not last. Baker, with his eyes on Hollywood, never looked back, and within five years McVea was dead from tuberculosis.

Other films from the same period also portrayed Indigenous Australians in a positive way, notably Robbery Under Arms (1920), The Gentleman Bushranger (1921) and Charles Chauvel’s Moth Of Moonbi (1926) in which Chauvel himself played a sympathetic role in blackface. Moth Of Moonbi was Chauvel’s first feature, and it only survives in part. Chauvel is one of Australia’s best known and most accomplished silent (and sound) filmmakers, and his films are particularly interesting for what they, sometimes inadvertently, say about white Australia’s fraught relationship with its ‘Aboriginal’ Other.

Among these positive films, The Tenth Straw (1926) stands out for a number of reasons.

– first, it stars a nameless Indigenous Australian tracker (that is, this person is the film’s sine qua non: the detective who solves the mystery;

– second, the sheer number of close-ups this person gets;

– third, the talent of the nameless actor:

– fourth, he gets to commit violence on a rich, evil white man as a necessary step in solving the mystery.

|

|

|

The Romance of Runnibede (1927) uses documentary footage of fire-making, and dancing imagery, body painting, menacing spears etc. to authenticate its outrageously melodramatic fiction, which culminates in this romantic and dreamlike image as the “White Queen”, whom an Indigenous Australian tribe has so long awaited, is spirited off into the bush, as if by fairies.

Among these more positive films there are two which deal with non-Australian indigenous ‘people of color’. The Betrayer (Beaumont Smith, 1921) and The Jungle Woman (Frank Hurley, 1926). In The Betrayer the Australian director, Beaumont Smith, locates an interracial romance in New Zealand where, “there is little evidence of social stigma attached to the proposed marriage of Stephen and Iwa [a “part-Maori girl” played by an actor identified only as “Mita”], perhaps because her appearance was entirely European” [10] – unintentionally underlining the racial taboos of his homeland. In The Jungle Woman the Australian director, Frank Hurley, locates a rather lurid melodrama involving “head hunters” and the film’s ‘other woman’, “a native girl, Hurana, played by Grace Sevieri”] in New Guinea, where Hurana dies by snake bite before her relationship can be consummated – unintentionally underlining the racial taboos of his homeland.[11]

Trooper O’Brien (1928).

O’Brien’s only boyhood companion is Mooli, a young white actor in blackface. Mooli knows horses and tracking and protects the young O’Brien. He is the Indigenous boy who might have figured in the Australian childrens’ cinema of the period, but does not.

The Birth of White Australia (1928) (title frame enlargement).

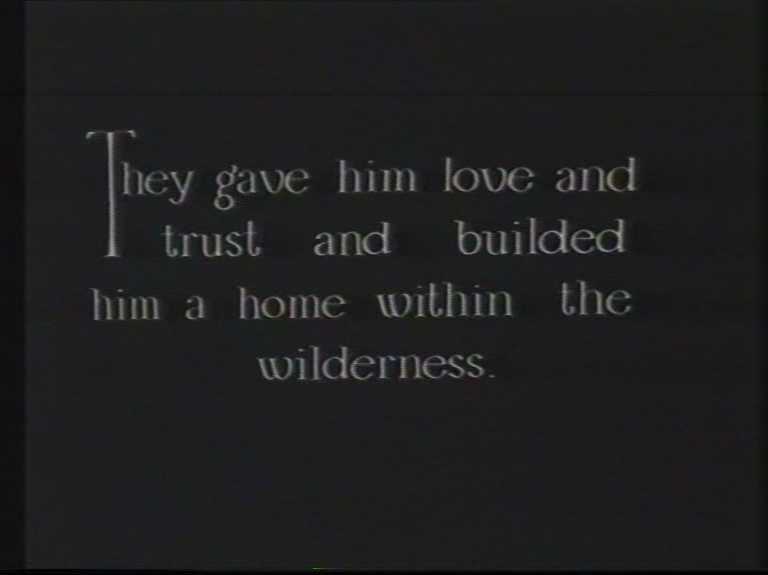

Phil Walsh’s The Birth of White Australia (1928) uses a range of tropes of ‘Aboriginality’ and a range of different types of footage (intertitles, documentary, stock footage, fiction films) to situate his version of The Birth Of A Nation (1915) in a land where the real danger is the Chinese and “The ethnic age has passed away / The primal race is with the dead, / And, visitants of yesterday, / The WHITE ‘invaders’ rule instead”. Walsh’s Indigenous Australians at first menace and kill some white newcomers, but the lone survivor of the massacre shoots and kills many members of “the primal race”before giving himself up for dead as his enemies surround him – and descending into madness. The white man’s madness, or his sense of his own superiority – it is not clear which – convinces the tribe to accept him and to do what he asks. He gives them gifts (beads, clothing, trinkets) and in return, “They gave him love and trust and builded him a home within the wilderness” (see above) – a bark house complete with a verandah outside of which members of the tribe sit and sway in rhythm, presumably waiting for further instruction. The white man clears the bush and begins to plough what he has cleared. “He lived at peace where savagery was rife and at his touch the sullen Bush began to smile.”

This shot by itself manages to do all that the outback and bush genres did. It vanishes Indigenous Australians from the land that was their own. In the film that inspired Walsh, the white Klu Klux Klan lynch African-Americans to achieve the “birth” of their nation. I suppose we must be grateful that Walsh’s film spares us those images of the Australian birth of a nation.

Coorab in the isle of ghosts

Introduction to Birtles.

Francis Edwin Birtles (1881-1941), overlander, was born on 7 November 1881 at Fitzroy, Victoria, son of David Birtles, a bootmaker from Macclesfield, England, and his wife Sarah Jane, née Bartlett. He was educated at South Wandin State School, and at 15 joined the merchant navy as an apprentice. In 1899 he jumped ship at Cape Town, South Africa, and tried to enlist with Australian militia, but was attached to the Field Intelligence Department as part of a troop of irregular mounted infantry until May 1902. He returned briefly to Australia, then joined the constabulary in the Transvaal as a mounted police officer. His experiences there equipped him with bushcraft skills in a semi-arid environment and he undertook several cycling and photographic excursions; his police service ended when he contracted blackwater fever.

Birtles disembarked at Fremantle, Western Australia, and on 26 December 1905 left to cycle to Melbourne, an achievement which attracted widespread attention. After brief employment as a lithographic artist, in 1907-08 he cycled to Sydney and then, via Brisbane, Normanton, Darwin, Alice Springs and Adelaide back to Sydney, where he was thereafter based. In 1909 he published the story of his feat, Lonely Lands, which he illustrated with his own photographs. That year he set a new cycling record for the Fremantle to Sydney continental crossing, then in 1910-11 rode around Australia. In 1911 he was accompanied from Sydney to Darwin by R. Primmer, cameraman for the Gaumont Co.: Across Australia was released next year. Birtles had continued on to Broome and Perth, then lowered his record by riding from Fremantle to Sydney in thirty-one days. By 1912 he had cycled around Australia twice and had crossed the continent seven times.

Birtles next turned to the motor car and in 1912 completed the first west-to-east crossing of the continent with Syd Ferguson and a terrier, Rex, in a single-cylinder Brush car. In 1914 with Frank Hurley as cameraman he made Into Australia’s Unknown (1915); next year he retraced their route and was responsible for the film Across Australia in the Track of Burke and Wills; in 1919 he made Through Australian Wilds, following by car the track of Sir Ross Smith. On his many other trips, with companions such as his brother Clive, he shot much film footage.

On 27 November 1920 at St Paul’s Cathedral, Melbourne, he married Frances Knight; they soon separated and she divorced him in 1922. In 1921 he and his companion Roy Fry had been extensively injured when his car caught fire near Elsey station while he was employed by the Prime Minister’s Department on a survey mission for the proposed north- south railway to Alice Springs; he later finished the survey by air. In 1926 he set motoring records from Melbourne to Darwin and Darwin to Sydney (seven days) in a Bean car named ‘The Sundowner’. By mid-1927 he had completed more than seventy transcontinental crossings. Impecunious, he depended on manufacturers to sponsor his expeditions and wrote about many of his journeys for newspapers and periodicals.

In July 1928 Birtles became the first person to drive from London to Melbourne, a nine- month part-solo journey completed in ‘The Sundowner’ which he donated in 1929 to a proposed national museum in Canberra. With M. H. Ellis he undertook an unsuccessful search for L. H. B. Lasseter. In the Depression he spent several years gold-prospecting in arid areas and discovered a payable gold-mine in 1934. On 11 February 1935 at St Mary’s Cathedral, Sydney, he married Nea McCutcheon. That year he published Battle Fronts of Outback (Sydney).

Survived by his second wife, Birtles died at Croydon of coronary vascular disease on 1 July 1941 and was buried in the Anglican section of Waverley cemetery.

[12]

1923. A story that might be a film: Coorab in the isle of ghosts

[Transcriber’s note: I have transcribed this text as faithfully as I was able. Where the intention of the text did not seem clear to me I have added comments in bold square brackets, thus: [comment]. WDR.]

As devils they screeched, and bit, and clawed. Fought in the jungle night blackness as only the devils of the unknown can fight. The tops of the gnarled tree trunks bent and crashed under the weight of the foetid vampires. Ghastly and ghostly things swept on noiseless wing, ever circling around about the melee.

Dense and dark, and of deadly perils were the adder-infested, sweltering undergrowths, deep, and mysterious, and vile smelling were the stagnant waters of the crocodile pool. Aboriginal Coorab, biding in his all-protecting hollow tree trunk on the edge of the lagoon, shivered in a fever of bodily fright and mental anguish. Bold defier of tribal laws, he had hungrily eaten of forbidden meat, the flesh of a young dugong, his totematic brother. Sweetest of delicacies reserved for the elders of the tribe. In wrath they now followed his tracks. For days he had tricked them with his knowledge of bushcraft, then to the Devil Lands he went, followed by his little dog Yowie. Here no mortal native dare follow, no native ever return to his tribe with his kidney fat nor blood in his meat. With tense drawn nerves he peered out of a crack into the intense darkness.

A rushing of wings, honk, honk, honking, flying swift and low, as wild geese passed over the surface of the saurian pool, passed onwards to more favoured regions. Yowie sniffed uneasily.

Then came Nature’s warning. Every creature receiving a telepathic message of unknown danger. Coorab was of the primitive. With thumping heart he listened. A tree branch waved noisily overhead; a heavy flopping thud struck the leaf decayed earth. A squirming mass of phosphorescent light glinted, and there lay a monster now, in stillness unseen, now in slithering movement, Outlined as though of fire.

Rippling along slowly, there came a 30 foot python. The tribal forest legend visualized.

Coorab closed his eyes tightly and touched low down close to his little companion. He had heard campfire tales told by his old man’s old man of a swamp[.] L — o — n— g fellah stomach which swallowed kangaroos even as they jumped, twisted men’s bones, and dared, the old woman alligator to defend her new mound of eggs.

Thumping by in great haste bounded a scrub wallaby. . . A cheeky, chattering native cat, now wholly terrified, hastily scrambled well out on to light branches, here, safe – at intervals he swore excitedly. Coorab too was safe. In weariness he slept and snored.

The booming of a falling tree aroused him from his cramped, half-sitting position. Then came the call of jungle hens, moo, moos of nutmeg pigeons. Glimpses of light overhead on the sparkling tree tops. A grunt of a cassowary. Coorab hoisted himself out, stiffly he climbed a wild fruit tree and feasted. Hungrily he gazed down at the fat water lilies of the lagoon. Hungrily a watchful pair of bubbles floated on its surface. Underneath shadowly loomed a menacing bulk balanced with outlying flat, opened web feet, broad tail, bent ready for a might[y] lunge towards a victim. [Note: it is possible that the spacing between words in this paragraph is intended to represent pauses for the reader of the text, and so I have indicated where it occurs.]

Coorab sniffed, and spat at the surrounding atmosphere. To-day he would go, follow the line of reedy swamps to the clear air of the coast. Of fish and of oysters he would eat, for these were

of the tribe of his wife. Hot was the sun shining on a shimmering sea. Weary was a lone dark figure on a long sand beach, searching among the debris of high tides for something to eat. He had looked too much last night, and to-day his spear could not hit the fishes. Of turtle eggs he had eaten three, all that were left over from the feast of a hungry iguana. Of green cocoanuts he had drank the milk. A floating, squashy bag of Japanese boat ration rice he tasted and slung away. He was tired. He would make his camp near those palm trees.

Half-buried in the wet sand was a barrel. He would make a well with this in a fresh water sand soak, so he unearthed it and rolled [it] to above [the?] high water mark. With a stone he punched in the top. The water inside splashed on to his hand. It was cold. It smelt nice. He tasted of

it. Bending over quickly, he put his head in and took a mouthful. It was cool, and it was hot. He sipped a “big fellah tuckout.” He would rest. He would go out on to that sea to hunt the dugong

in the canoe which he had just found. [New paragraph?] So he paddled out. On the bows Corrab

stood up boldly as the canoe ranged up overhead of the diving dugong. Deep and strong had the spear been driven home. Deep down, too, he dived, turned over, and stuffed paper bark into the mammal’s nostrils. Now, triumphant, he sat on the floating creature’s head, and started to make it dead. In surprise and fright he looked around. Gone was the canoe, going was the dugong; to coral beds below it dived. Through coral reefs Coorab swam strongly. Swirling tide waters swept him on to a sand beach. Dazed, he gazed around.

Then, close by, in savage silence, something was moving over the burning hot sands, moving spasmodically towards him. Gone was his strength.

Mother of all things totematic! Coorab, painted war maker, dusky breaker of tribal laws, on bended knee, was trying, in a few garbled words to hurriedly explain the totematic wrong-doings of a lifetime.

That added tongue struck. Those fierce jaws wavered. Those descending, rending hand claws. Deadly rainbows. Circular lighting. What was that? Crash!

Yowie, his faithful dingo mongrel, was yapping furiously. Blady grasses of the beach line parted cautiously, revealing the peering face of old wife, Kanaly, who for many days had tracked him over mountain and gully, jungle and swamps, to the blue seas of her native land. Thirstily he sat up to drink of the courage-giving yellow water, but, in his struggles, as he “sat on the head of the fat dugong?” the capsized barrel had rolled back into the sea, and was now drifting away on the outgoing tide.

The hall was crowded, and the woman speaker was waxing eloquent. “Yes,” she cried emphatically, “women have been misjudged for ages.” They have suffered in a thousand ways. Here she paused to give her audience time to consider this momentous statement. “There is one way in which they never suffered and never will,” said a meek little man from the back of the crowd. The lecturer gave him a frigid look. “And in what way is that [?},” she enquired. “In slience [sic]!” replied the little man, as he sank into his seat.

[13]

This trivial story appears to be no more nor less than a bad joke. But the way that it is told makes it more interesting than that. Once Birtles begins to channel Coorab, to articulate Coorab’s psyche, his writing changes and becomes all sensation. “That added tongue struck. Those fierce jaws wavered. Those descending, rending hand claws. Deadly rainbows. Circular lighting. What was that? Crash!”

1928. Coorab in the island of ghosts

Beginning

Francis Birtles begins his 48 minute film of Coorab In The Island Of Ghosts with a fantastical image of a winged, toothed, clawed monster drenched in purple,

for which he then takes credit in the next title: “Visualized by FRANCIS BIRTLES Australian Overlander”.

This title is replaced by an image of a man in an automobile (Birtles) surrounded by Indigenous Australians who appear to be helping him avoid/kill a crocodile, all drenched in the self-same purple – presumably the ‘reality’ of the fantastic beast in the opening title.

Only then does the film proper begin – by voicing William Shakespeare

which suggests that the real crocodile and the fantastical one have both been “staged” by Birtles.

And now the titles come thick and fast: “And all the men and women merely players…” / “And one man in his time plays many parts, his acts being Seven Ages.” / “At first the Infant”… /

Something evil has happened here. Birtles has presented an image surely intended to shock and titillate that just as surely exploits and denigrates the people it displays – and he has presented it as educational, as documentary. Birtles has articulated this image; he has uttered it: this footage is in his voice (the implicit voice of one who has staged, authored a film). Moreover, Birtles has done this because the people he is (re)presenting here are Indigenous Australians. He could not have shown a white woman and child doing what the Indigenous mother and child are doing without at least provoking community outrage and, quite possibly, legal prosecution. Here, at the beginning of Coorab, viewing askew with my/our white eyes, I/we can experience an emblematic moment of colonization – civilization dealing with savagery.

Titles of edited Shakespeare and ‘documentary’ footage of Indigenous Australians follow each other again: “. . . And then the whining school-boy” / “. . . the Smiling Lover” . . . / (who, we will learn later, is Coorab).

. . . “And then the soldier, full of strange oaths” . . .

. . . “ now the Justice with eyes severe . . . “ / . . . the next scene shifts into . . . /

Apparently this image is intended to illustrate Shakespeare’s “lean and slippered pantaloon”, but we cannot be certain, for Birtles tells us nothing about it.

. . . “and the last scene of all” . . .

This man, and this image, display the dignity of epic figures. I think this quality too is due to Birtles – the man and the photographer — and is intentional. Just as the sensation seems to have captured him in the image of the mother and child, so now the quite different sensation of this old man has him in its grip. So moved is he that (I want to believe) he cannot even bring himself to add Shakepeare’s words, “Last scene of all / That ends this strange eventful history, / Is second childishness and mere oblivion, / Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

Ending

For the pathos-laden ending of Coorab, Birtles misquotes the lyrics of “Somewhere a voice is calling” (1901; Eileen Newton, lyrics; Arthur F. Tate, music) as he misquotes Shakespeare’s “All the world’s a stage” at the film’s beginning – slightly rewriting the words and interleaving them with visuals of Coowangama mourning Coorab’s death.

Dusk, and the shadows falling,(“Dusk when the shadows deepen;”)

|

|

|

O’er land and sea; (“Over land and sea;”)

Somewhere a voice is calling, (“Somewhere a voice is calling”;)

Calling for me! (“Calling for me”;)

End title

The end title elides the last four lines of the lyric: “Night and the stars are gleaming, /

Tender and true; / Dearest! my heart is dreaming, / Dreaming of you!”

Here, in these last scenes, moved by his vision of himself as an Other, and surely moved as I am/we are by the performances of Coorab and Coowangama, Francis Birtles has created the first epic of Australian Indigenous cinema..

Notes:

[1] I am grateful to Jeremy Barham, Anna Dzenis, Kathyrn Bird, Ross Gibson, Rick Thompson, Andrey Walkling, Judy Routt, and always Diane for things they did and said during the research and writing of this essay.

[2] This production still heads my essay, “Dad and Dave Come to Town (1938)” in The Cinema of Australia and New Zealand, edited by Geoff Mayer and Ken Beattie (Wallflower Press, 2007), 31-40. However, the text you are reading here is entirely different from what I wrote for Mayer and Beattie.

[3] William. D. Routt, “Are You a Fish? Are You a Snake?”: An Obvious Lecture and Some Notes on The Last Wave“. In Critical Multiculturalism, edited by Tom O’Regan, pp. 215-231. Continuum 8.2, 1994.)

[4] See Ina Bertrand, Cinema in Australia, p. 12. Bertrand here, as always, presents her material without interpretation. The speculations which follow are mine alone.

[5] Haddon, Alfred Cort (1855-1940) by Steve Mullins (Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 14, [MUP], 1996.) http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/haddon-alfred-cort-10386

[6] Ina Bertrand, Cinema in Australia, p. 48.

[7] D.J. Mulvaney, “Spencer, Sir Walter Baldwin (1860-1929) “ in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 12 (Melbourne University Press), 1990. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/spencer-sir-walter-baldwin-8606

[8] Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, Melbourne, OUP 1980, p. 3.

[9] Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, p. 4.

[10] Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, p. 139.

[11] Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, p. 218.

[12] Terry G. Birtles, “Birtles, Francis Edwin”. Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 7, (MUP), 1979. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/birtles-francis-edwin-5244

[13] Francis Birtles, “Coorab in the Island of Ghosts.” The Register, Adelaide, SA, April 24, 1923, p. 10. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/rendition/nla.news-article64182104#