2018 marked the fortieth anniversary of John Carpenter’s pivotal slasher film Halloween (1978) and the release of yet another sequel, Halloween (David Gordon Green, 2018), in which Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis), now a grandmother, is determined to eliminate her brother Michael Myers after he escapes from prison. Since 2005 there have been a range of other remakes, prequels and sequels based on Carpenter’s work: Assault on Precinct 13 (Jean-Francois Richet, 2005), The Fog (Rupert Wainwright, 2005), Halloween (Rob Zombie, 2007), Halloween II (Rob Zombie, 2009), and The Thing (Matthijs van Heijningen Jr, 2011), while reboots of Escape from New York (1981) and Big Trouble in Little China (1985) are in various stages of development. Carpenter, though, has not made a film since The Ward (2010). Indeed, after the commercial and critical failure of Ghosts of Mars (2001), he announced his withdrawal from filmmaking at the age of fifty-three, citing fatigue from more than twenty-five years of writing, directing, scoring, and occasionally editing his films. His physical appearance at the time reinforced the impression that he was exhausted: he was white-haired, balding, and haggard looking. If the critical consensus at the millennium was that Carpenter was also drained creatively, then the continuing interest in his earlier films suggest that his work remains potentially profitable and culturally significant. This prompts a question – whatever happened to the ‘master of horror’? This article explores Carpenter’s ‘retirement’ through an analysis of two short features he made for the television anthology series Masters of Horror, Cigarette Burns (2005) and Pro-Life (2006), as well as Ghosts of Mars and The Ward. I will argue that these texts can be interpreted as examples of “creative nostalgia” and a self-conscious erasure of ‘John Carpenter’. [1]

Reputation

Carpenter’s critical reputation arguably rests on the films he made from Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) to They Live (1988). According to Ian Conrich and David Woods, Halloween and The Thing (1982) are firmly situated in “the pantheon of modern horror”. [2] Adam Rockoff contends that Halloween was “an almost perfect exercise in terror”, and for many people its financial success and enormous influence on the subgenre made it the “the most important slasher film” ever made. [3] Although The Thing was poorly received on release, its tense atmosphere, stunning special effects, and moody Ennio Morricone score have seen its reputation grow significantly over time. [4] Some critics now regard it as the “the most strikingly original and visually explicit example” of the ‘body horror’ subgenre. [5] Escape from New York is a notable predecessor of the contemporary action film and featured a memorable performance by Kurt Russell as the anti-hero Snake Plissken. Marco Lanzagorta claims that Big Trouble in Little China “features of some of the best martial arts choreography of its time in a Western film”. [6] Assault on Precinct 13, Carpenter’s reworking of Rio Bravo (Howard Hawks, 1959), was distinguished by its taut narrative, widescreen compositions and moments of ‘pure cinema’. The Fog (1980) was a successful ghost film marked by “Carpenter’s virtuoso handling of the elements of horror and suspense”. [7] Richard Corliss praised Christine (1983), a Stephen King adaptation, as a “deadpan satire of the American man’s love affair with his car … and one lean mean funny machine”. [8] Carpenter’s ‘golden age’ concluded with They Live, a science fiction satire of corporate greed and consumerism in the Reagan-Bush era. Simon Sellars suggests that in the process Carpenter “reappropriates Hollywood values in a cheap ‘bubblegum’ universe that invades, reinvigorates and repopulates … the ‘desert of the real’ of late capitalism”. [9]

By contrast, Carpenter’s reputation deteriorated throughout the 1990s as he directed a number of remakes, adaptations, and sequels, most of which performed poorly at the box office. In a negative review of Vampires (1998), Kim Newman observed that Carpenter’s “decline over the last ten years has been alarming”. [10] Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992) was an uneasy mix of sci-fiction and comedy “shot down by a confused screenplay that never manages to find the right tone”. [11] Roger Ebert stated that, “Every character and every line of dialogue … is demoralized by the countless times they’ve been recycled”. [12] Philip Kerr asserted that In the Mouth of Madness (1995) is clearly inferior to H.P. Lovecraft’s unacknowledged source material and “just isn’t very frightening” (1995: 53). [13] Desson Howe dismissed it as “a bewildering, boring assembly of rock-video-surreal nightmare sequences”. [14] Todd McCarthy castigated Village of the Damned (1995) as “a risible remake of the British 1960 sci-fi classic”. [15] The sense of ennui increased when Carpenter made Escape from L. A. (1996). One reviewer opined, “Every time we’ve seen this director’s name above the title for the last 12 years, … it’s been a sign that we’re about to ingest something that’s not good for us …. Escape is a pathetic sequel”. [16] Newman complained: “A monumentally misconceived sequel, Escape from L. A. is the huge, shonky blemish on the magnificent history of John Carpenter and Kurt Russell”. [17] Vampires may have been Carpenter’s only commercial success in the decade, but Michael O’Sullivan derided it as “styleless and unsexy”, [18] while Newman rued that, “it is rarely as exciting as it would like to be and never remotely scary”. [19]

The hostility towards Carpenter was particularly evident in the reception of Ghosts of Mars, “which was scorned by most critics and audiences in both America and Europe”. [20] Derek Malcolm protested that, “Ghosts of Mars doesn’t just scrape the bottom of the barrel. It is the bottom of the barrel as far as this once talented director is concerned”. [21] For some, Ghosts was not just a bad film, but Carpenter was guilty of technical incompetence. Robert Koehler ridiculed the film’s “comically antique” special effects, [22] while Newman grumbled, “Given that it sets out to be a low-rent action picture, it’s amazing how many things that Ghosts of Mars finds to do wrong”. [23] Critics also deplored Carpenter’s decision to revisit his own work in the film (as I discuss below, it evokes several of his earlier films). Kerr accused him of “feeding off his own corpse” and lamented that it was “sad to see a once inventive talent eating his own excrement”. [24]

Carpenter’s ‘Creative Nostalgia’

Carpenter has always been something of a cannibal. Raiford Guins and Omayra Zaragoza Cruz assert that, “Carpenter positively revels in repetition. Remakes, adaptations and sequels, as well as recurring themes, images, sounds and actors firmly imprint his oeuvre”. [25] His films are full of allusions to both his own work and that of other filmmakers. [26] Prince of Darkness (1987) is a salient instance of Carpenter’s proclivity for intertexuality. The film focuses on a group of scientists who investigate an artifact found in an old Catholic church and find that it contains a Satanic force capable of destroying the universe. Robert Cumbow has shown it includes multiple citations of nearly all of Carpenter’s previous films up until that point. [27] For example, the scientists cannot leave the church because it is surrounded by homeless people under Satanic influence. Thus, the film employs the ‘siege’ scenario found in Carpenter films such as Attack on Precinct 13, Halloween, The Fog, The Thing, and Prince of Darkness, in which characters are confined within particular spaces while under threat from a hostile external force. [28] As Cumbow argues, the siege format references both Howard Hawks and Night of the Living Dead (George A. Romero, 1968), while the recovery of an ancient, potentially alien, object draws on Quatermass and the Pit (Roy Ward Baker, 1967), another key influence on Carpenter. [29] There are also references to Jean-Luc Godard, the projectile vomit scene from The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973), The Shining (Stanley Kubrick), and even La Jetée (Chris Marker, 1962). In Cumbow’s opinion, these qualities make Prince of Darkness “Carpenter’s definitive film” because it unifies his work while engaging with a dozen tropes from the genres of horror and science-fiction. [30]

Gains and Cruz develop their concept of “creative nostalgia” in opposition to the Frankfurt School’s negative view of the repetitive and derivative qualities of mass entertainment. While they acknowledge that Carpenter’s work frequently recycles individual films as well as entire genres, they challenge the dominant critical reading of his 1990s films. They argue this output during the decade can be regarded as a form of imaginative repetition. On the one hand this affirms his position as an auteur: “Directorial enunciation is … conceived of a relationship to the past”. [31] On the other it involves an inventive way to “disrupt the parameters of homogeneity” of the horror genre. [32] The latter can be discerned in Vampires, a horror-action hybrid located in the American South-West. While it may be a vampire film, it eschews much of the lore and iconography associated with the sub-genre. As the lead vampire hunter Jack Crow (James Woods) a typical Carpenter anti-hero, tells new team member Father Guiteau (Tim Guinee), “Forget whatever you’ve seen in the movies: they don’t turn into bats, crosses don’t work.” Indeed, the film’s setting, costuming, frequent travel, and violence suggest that it is a disguised Western. Vampires also displays distinct Hawksian qualities. There is an emphasis throughout the film on Hawksian values such as “action as a physical index of moral value”. [33] Initially, Crow leads an all-male group of vampire hunters (funded by the Catholic Church) which is held together by the codes of male professionalism and rituals of male bonding that have been associated with Hawks’ work. We learn that vampire hunting is governed by a set of rules because mistakes get people killed. When the group arrives at an isolated farmhouse/vampire ‘nest’, Crow tells his men that the raid will be conducted “strictly by the book”. After eliminating the coven, they celebrate in an alcohol-fuelled orgy with prostitutes, much to the annoyance of the local sheriff who has been ordered to ignore their excesses. Gains and Cruz assert that Vampires appeared at a time “when it [was] uncouth to occupy the Hawksian and Fordian legacy”, and that these elements were out of kilter with other generic trends. [34] As such, they insist that the film can be interpreted as a riposte from the director of Halloween to the highly self-conscious teen slasher films of the 1990s such as Scream (Wes Craven, 1996) and I Know What You Did Last Summer (Jim Gillespie, 1997). [35]

Ghosts of Mars

Ghosts of Mars is a horror/science-fiction film set in 2176 on a planet gradually being colonised and terra-formed. A small contingent of police travels by train to Shining Canyon, a remote mining town, to collect a notorious criminal, James “Desolation” Williams (Ice Cube), accused of murder, from the local gaol. The town seems largely deserted. An ancient force released accidentally at a mining site has possessed most of the residents; transformed into a mob (the titular ghosts), they scarify themselves and murder others. The police are forced to defend themselves in the police station, and form an alliance with Williams and his compatriots as they wait for the train’s return. After a series of battles, only Williams and Lieutenant Melanie Ballard (Natasha Henstridge) survive. Williams escapes from the train, leaving Ballard to report what happened to her incredulous superiors. The film ends with Chryse, a major Martian city, under attack from the ghosts.

Carpenter’s creative nostalgia is evident in Ghosts of Mars in a number of ways. The barren town and the arid, dusty surroundings evoke images of the Western. This emphasises the continuing influence of Howard Hawks and Rio Bravo while also pointing to Carpenter’s established affection for the genre. [36] Another familiar trope is the anti-hero: Desolation Williams resembles Jack Crow and the characters played by Kurt Russell in the Escape films, The Thing, and Big Trouble in Little China. Tom Whalen argues that the ghostly possession or infection of characters recalls similar occurrences in The Thing, Prince of Darkness and In the Mouth of Madness, while “the terror of the Other” that the ghosts represent can be found in Halloween, The Fog, The Thing, and Prince of Darkness. [37] The ghosts’ gruesome appearance and behaviour means they resemble zombies rather than immaterial spectres, which is perhaps a further allusion to Romero’s work. Finally, the open ending implies that the fast-moving ghosts will overrun the planet, thus suggesting that the film is the fourth of Carpenter’s apocalyptic films (the previous ‘trilogy’ consists of The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness).

However, what Joseph Maddrey describes as “a pretty straightforward game of ‘cowboys and Indians’” is more complex than its narrative premise might indicate. [38] Carpenter does not simply regurgitate his own work in Ghosts of Mars as critics suggest. Rather, he undertakes a calculated manipulation of his other films, Assault on Precinct 13 in particular. For example, Ghosts reverses the gender and racial dynamics of the central duo from the original film. In Assault, Lieutenant Bishop (Austin Stoker), the officer in charge of the soon to be defunct police station, is African-American, while Napoleon Wilson (Darwin Joston), the high-profile criminal who fights with him, is white. Bishop’s equivalent in Ghosts is Ballard, played by a white actress. Correspondingly, Wilson’s part is played by an African-American actor. Ballard’s role also incorporates the figure of the ‘Hawksian’ woman in Assault, Leigh (Laurie Zimmer), whose name is a nod to Hawks’ collaborator Leigh Brackett. However, Ballard is not a secondary figure, a capable, resilient and attractive woman who has earned her place among a group of male professionals. Rather, she is actually the film’s protagonist, taking on the leadership role after the death of Captain Helena Braddock (Pam Grier). The emphasis on female subjectivity occurs at a broader social level. While Carpenter often constructs a heavily masculine environment in his films, the Martian colony in Ghosts of Mars is explicitly matriarchal. (When Ballard is questioned about the events at Shining Canyon, she is informed that she does not need a lawyer because her “rights are protected by the Matronage”.) Not only is masculinity in decline in this environment, so is heterosexuality. Braddock is openly gay, and it is implied that another policewoman, Kincaid (Clea DuVall), is also a lesbian. The film also mocks the overtly heterosexual Sergeant Jericho (Jason Statham) as he repeatedly attempts to use his status as a “breeder” to seduce Ballard during the mission (“I wouldn’t want to miss an opportunity”) regardless of the circumstances.

One of the interesting aspects of Ghosts of Mars is that it is structured around a series of flashbacks from Ballard’s perspective as she presents her report to her superiors. Some of these flashbacks consist of material not actually witnessed by Ballard herself, but reports from other team members. Jericho, for example, witnesses the Martians executing captives and is shocked to see Braddock’s severed head on a stick. This narrational device of flashbacks within flashbacks is quite unusual in a Carpenter film. It serves more than the purpose of informing us about what happened in Shining Canyon. In my view, the flashbacks invite us to look backwards across Carpenter’s work. Is it just a coincidence that Ghosts of Mars, the director’s ‘final’ film before his retreat from the cinema, reverses and transforms Assault on Precinct 13, his first major critical success? The notion that Ghosts represents a culmination of Carpenter’s work is reinforced by its ending. After Ballard has finished her story, she returns to her room to rest. Sometime later Williams rouses her unexpectedly; he has decided to forsake his ruthless self-interest and join the battle for Chryse. As they walk, they discuss the possibility of exchanging roles in life before dismissing the idea. Williams says, “Let’s just kick some ass” and Ballard responds, “It’s what we do best.” This show of mutual respect and camaraderie resembles Bishop’s and Wilson’s memorable exit from the police station at the conclusion of Assault on Precinct 13. In the final shot Williams/Ice Cube turns his head, looks directly at the camera, and smiles. Of course, this playful, self-conscious gesture acknowledges the audience, inviting us to share in the pleasures of the action film, but it also constitutes a farewell nod or a sense of closure.

Cigarette Burns

The Masters of Horror series consisted of self-contained short features, each about an hour long. The project emanated from a series of dinners for film directors organised by Mick Garris, who produced the series for Showtime. Some of the directors involved were Stuart Gordon, Tobe Hooper, Dario Argento, Joe Dante, Larry Cohen, and Takashi Miike (whose episode proved too controversial for the network to screen). As Ben Kooyman points out, the series raises interesting questions about identity and genre. The group of directors was all male and largely white, and members did not necessarily have to be accomplished or even experienced horror directors. [39] Cigarette Burns and Pro-Life are unusual projects for Carpenter: he did not write the scripts, nor did he shoot them in his preferred widescreen format; his son Cody composed the music for both films. Nonetheless, they both display traits of creative nostalgia as well as some figural references to Carpenter.

Cigarette Burns focuses on the search for a print of a near mythical horror film, La Fin Absolue du Monde/The Absolute End of the World. Mr Bellinger (Udo Kier), a mysterious, wealthy private collector, hires Kirby Sweetman (Norman Reedus), a film researcher and owner of a repertory cinema, to find the film. Its legendary status is connected to its first and only public screening, which resulted in the murders of four audience members, while the remainder went insane. Feeling guilty about the suicide of his wife Annie (Zara Taylor) and desperate to repay a large debt to his angry father-in-law Walter Matthews (Gary Hetherington), Sweetman undertakes an increasingly hazardous journey to locate the print as he encounters people associated with the original production and screening. During his travels he learns that an angel was mutilated on set, and this violation has given the film its extraordinary effect on anyone who watches it. (Bellinger holds the angel prisoner, while the wings hang on his wall like a big game trophy.) Eventually he succeeds, and hands over the print. However, Bellinger and his butler both go mad after watching the film. The butler hacks out his own eyes and scarifies his flesh, while Ballinger eviscerates himself and threads his intestines through the projector. Matthews confronts Sweetman at Bellinger’s mansion. They both watch the film and after it finishes Sweetman kills the older man and then commits suicide. The angel, who has been released by the butler, takes possession of the print.

The title refers to the belief that small markers are placed on film prints as a signal to projectionists that a reel change is imminent. (Sweetman’s projectionist snips a frame from Profondo Rosso [Dario Argento, 1975] for his collection of stills because it contains a cigarette burn.) It resonates in a number of ways. Cigarette burns can leave a mark on an object or a scar on a person (burning someone with a cigarette is a common torture tactic). Engraving something on to the film strip points to the history and materiality of the image, including the elided conditions of production. In the context of the film it gestures to the suffering that occurred during the making of La Fin Absolue du Monde. It also connects Sweetman to his past. As he moves closer to obtaining the print, he experiences hallucinations of his dead wife that originate in a large circle or cigarette burn that we see on the screen. [40]

The title of La Fine Absolue du Monde can be read as a reference to Carpenter’s earlier apocalyptic films. The central premise of Cigarette Burns – that a text can blur reality and fiction, thereby generating horrific effects for the audience – also links it specifically to In the Mouth of Madness. In the latter, John Trent (Sam Neill) is an insurance investigator hired by a publishing company to find their missing star author Sutter Cane (Jurgen Prochnow), whose novels have a highly disturbing impact on readers. Trent tracks Cane to a small New Hampshire town only to find that Cane has acquired the power from Lovecraftian monsters to transform the written word into reality, and that he is nothing more than a character in Cane’s latest novel, In the Mouth of Madness. The book’s publication causes a pandemic of psychosis, which parallels the self-mutilation and homicidal violence that occurs after viewers watch La Fin Absolue du Monde. At the end of the 1995 film, Trent sits in a cinema watching ‘himself’ in a ‘John Carpenter’ adaptation of Cane’s novel. Carpenter’s “self-reflexivity is oppressive”. [41] Trent is incorporated into Cane’s text, unable to escape, while the angel laments that he is bound to La Fin Absolue du Monde like a “soul to the flesh”.

Sweetman’s hallucinations also connect Cigarette Burns to Japanese techno-horror, particularly Ringu (Hideo Nakata, 1998). The images of his dead wife originate in a large circle or ring, a fairly obvious reference to Nakata’s film. At the onset of each hallucination, both Sweetman and the audience are dealt a short, sharp visual jolt. This kind of jump scare is a typical strategy of successful contemporary Japanese techno-horror films, which employ suggestive horror techniques rather than explicit violence. Both films explore the capacity of visual media to produce a violent response. Characters in Ringu die within seven days if they watch a mysterious videotape – thus both films are concerned with knowledge and transgression. Colette Balmain argues in relation to Ringu that it is via technology that “the past reasserts itself. As such, technology metaphorically and literally signifies death”. [42] In Ringu a young woman, Sadako (Rie Ino), is brutally murdered and thrown into a well, while the small amount of footage from La Fin Absolue du Monde that we actually see indicates that, in addition to the desecration of the angel, another man was stabbed, and a woman was shackled to a wall. Thus, the videotape and the print acquire their supernatural power because the power of a traumatic history has somehow inscribed itself on to the image. And, as if to emphasise the circularity of Cigarette Burns’ repetition of Ringu, in Sweetman’s final vision Annie steps out of the burn/ring and into Bellinger’s theatre thereby imitating the emergence of Sadako’s ghost from a television set in Ringu.

The scenes of self-mutilation and corporeal disfigurement involving Bellinger and the butler provide Carpenter’s film with a visceral dimension that one might expect from the director of The Thing. Their self-harm is also an allusion to the way in which the colonists behave in Ghosts of Mars after they have been possessed. At the same time, the explicit violence shown in Cigarette Burns has affinities with some aspects of ‘torture porn’ films such as Hostel (Eli Roth, 2005) and Saw (James Wan, 2004). In particular, Cigarette Burns contains a ‘snuff’ movie episode that resembles the Slovakian torture room sequences in Hostel. [43] One of Sweetman’s contacts Henri, a French film archivist who was the projectionist at a private screening of La Fin Absolue du Monde (and who survived by not watching the film), provides him with information about a radical performance artist (Douglas Arthurs) who has a range of items associated with the film, including some production stills. The artist’s warehouse seems to be decorated with human skin. After a conversation about the artifacts, Sweetman is drugged. When he regains consciousness, both he and his female taxi driver have been bound and gagged. The artist proceeds to hack the driver’s head off with a machete while her blood spurts graphically from her neck. [44] He films her murder in the name of art because conventional representational practices have become so timid. His motivation is similar to that of some of the wealthy torturers in Hostel who pay large sums of money to experience the thrill of murder because they have become so jaded with other pleasures. Sometime later, Sweetman reawakens to find himself untied and the artist lying injured on the floor; his henchmen have disappeared. Sweetman tortures the latter for information by jabbing his fingers into the man’s bleeding neck; this parallels the manner in which survivors in torture porn films use their captors’ tactics against them in order to escape.

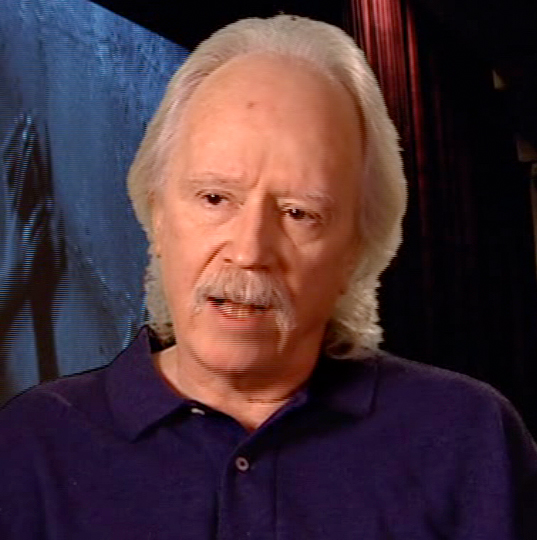

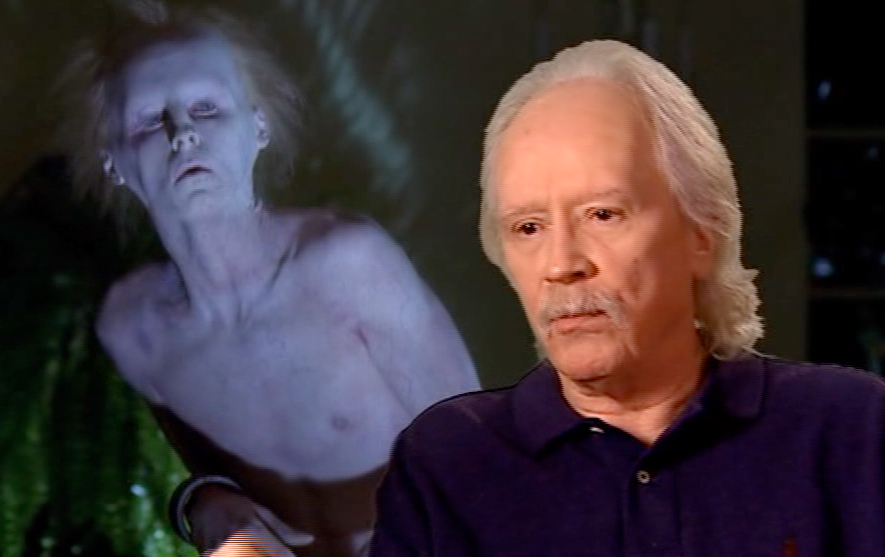

Cigarette Burns does more than invoke genre trends or Carpenter’s earlier films, it also includes a poignant and pointed reference to Carpenter himself through the figure of the angel. The pale, ageing creature with white thinning hair that stands shackled on display in Bellinger’s mansion bears more than a passing resemblance to John Carpenter at the time of production. (See figures 1-3) How do we regard this miserable figure whose timorous voice, listless gestures, and visible scars are stark reminders that the “blood of God” that once flowed through him (as the performance artist says) has now been drained? The angel’s predicament in Cigarette Burns can be interpreted as self-reflexive commentary on Carpenter’s position. In 1996 Carpenter said memorably in an interview, “‘In France, I’m an auteur. In England, I’m a horror movie director. In Germany, I’m a filmmaker. In the U.S., I’m a bum”’. [45] As Muir says about this frank self-appraisal, “There is a real sadness in that remark”. [46] Eight years later, it is tempting to read the angel’s circumstances as a metaphor for Carpenter’s assessment of his own situation: exhausted, his ‘wings clipped’, a captive of those with wealth and power. (Hence the ironic aptness of Bellinger’s fate. If Hollywood can be understood as an industry that produces mass culture, that is, it is a cultural ‘sausage factory’, then here one of the power brokers or ‘money men’ transforms his own intestines into sausages as he feeds them into the gate of the projector.) In terms of creative nostalgia, his seminal contributions to the horror genre are in danger of being forgotten, even as J-horror and torture porn flourish. The angel departs Cigarette Burns with his scars and the elusive print. Rather than gesturing to Carpenter’s reacquisition of creative autonomy, let alone his triumphal return to filmmaking, this exit is another stage in his withdrawal from cinema. He may have taken possession of the ‘final cut’, been restored to his proprietorship, but, weary and enfeebled, he is reduced to a proper name: “John Carpenter’s …”

Figure 1. |

Figure 2. |

Figure 3. |

Pro-Life

By comparison, Pro-Life is a more straightforward and less intertextual film. Angelique (Caitlin Wichs), a pregnant teenager seeks an emergency abortion from a local clinic even though her father Dwayne (Ron Eldard) is a fervent pro-life campaigner with a history of harassing the clinic. Convinced that he has orders from God, Dwayne and his three sons break into the clinic compound. They go on a rampage, killing a security guard by blowing his head open with a gun, as well as another father trying to flee with his wife and pregnant daughter. Angelique’s pregnancy progresses at an abnormally fast rate because she has been raped by a demon. The clinic director Dr Kiefer (Bill Dow) shoots back, mortally wounding one of Dwayne’s sons. Dwayne overwhelms the doctor and murders him by giving him a rectal ‘abortion’ while he is still conscious. The girl gives birth to human-demon hybrid. However, the voice of God turns out to be the demon. He emerges through the floor of the clinic and kills several people. Angelique shoots the child through the head, and the demon departs forlornly with his dead spawn.

Pro-Life is one of Carpenter’s siege films, but contains some interesting variations that are further evidence of his penchant for recombining textual elements. His siege films usually create an “Us and Them” dichotomy in which the defenders are delineated individuals who exhibit the skills associated with Hawksian masculinity. While group dynamics are often more fractious in Carpenter films than in Hawks’ work (thus the influence of Night of the Living Dead), there are at least attempts at teamwork in texts such as Assault on Precinct 13, Prince of Darkness, and Ghosts of Mars. By contrast, the numerous invaders in these films often function as depersonalized, expendable, and largely unsympathetic ‘others’. However, as David Woods has argued, the distinct boundaries between protagonists and antagonists are far more fluid than they appear initially in 1990s films such as Memoirs of an Invisible Man and Village of the Damned. [47] Vampires also develops sympathy for two newly created vampires: Crow’s offsider Montoya (Daniel Baldwin) and Katrina (Sheryl Lee), the woman who bites him. Despite his transformation, Montoya assists Crow in foiling the plans of the vampire leader Valek (Thomas Ian Griffith). In return, Crow grants the couple temporary dispensation at the end of the film.

In Pro-Life the clinic workers, patients and family members theoretically occupy the position of defenders. Dwayne and his gun-toting sons function as the invading force; their savagery and needless violence appears to construct them as the external ‘others’ for the audience. The film devotes comparatively little time to the issue of group dynamics. The people inside the clinic are located in different parts of the building and do not coalesce into a recognizable group. Nor do they exhibit the kind of physical competence that generates mutual respect. Dr Kiefer, the clinic’s only armed defender, is a clumsy figure that hides behind body armour. On the other hand, it is actually Dwayne who most closely resembles the typical Carpenter anti-hero. He is decisive, vigorous, skilful, and displays tactical nous. Moreover, Dwayne and his sons are defined individually, and they are somewhat sympathetic at different points in the narrative. As a result, it is far from clear with whom the audience is supposed to identify. The film’s ideological position is equally messy. While it obviously touches on the abortion debate, it does not canvass the issues in a detailed manner, let alone offer a coherent perspective on this important issue in American politics.

Pro-Life contains an explicit reference to The Thing. In a key scene in The Thing Dr Copper (Richard Dysart) applies defibrillation paddles to Norris (Charles Hallahan). The monster erupts out of Norris’ body and Copper’s hands are severed brutally in the process. The creature menaces the crew of the scientific base, but they destroy most of it using a flamethrower. One of the remnants of the thing resembles a lobster with long, thin legs. It tries to scuttle away as the group look on, absolutely astonished. Before it is killed, the stoner character Palmer (David Clennon) delivers what is perhaps the film’s most memorable line, “You’ve gotta be fucking kidding!” The demon baby in Pro-Life and the lobster creature in The Thing look remarkably similar. Dwayne reinforces the allusion by referring Angelique’s child as “that thing”. (See figures 4 and 5)

Figure 4.

The mother’s destruction of her grotesque child can also be interpreted allegorically. As I said earlier, The Thing is an important entry in the body horror subgenre. The analogue special effects used to configure the alien species are extraordinary and still compare favourably with more recent CGI work. These are used vividly when the thing reveals or transforms itself: when the infected Norwegian dog assails the other huskies in an animal pen, when it emerges from Norris’ abdomen, and during the blood serum test when Palmer’s head splits open and the thing tries to swallow Windows (Thomas Waites) whole. These cardinal examples of body horror demonstrate the plasticity of the body: the ability of the genre to represent the manner in which the organic can be altered, entered, fragmented, and destroyed. These sequences can also be interpreted as a form of hideous birth through incorporation. The thing reproduces itself by first absorbing and then imitating biological organisms from this world. If the demon baby in Pro-Life is an allusion to Carpenter’s iconic contributions to the genre, then its execution marks the decline or erasure of his legacy, that is, his own monstrous progeny. This impression of self-negation is arguably reinforced by Dr Kiefer’s murder. The death of the clinic’s director via a rectal abortion can be read as a metaphor for the death of the film director. Like the angel in Cigarette Burns, the director’s blood is drained from him. Moreover, Dr Kiefer is slain by a Carpenter archetype, which is just one more irony in a film called Pro-Life.

Figure 5.

The Ward

John Carpenter’s most recent film is The Ward. Set in rural Oregon in 1966, it focuses on Kirsten (Amber Heard) who is confined to a locked psychiatric ward for young women after burning down an old farmhouse. She takes the room of Tammy (Sali Sayler) who was killed in the opening scene after being stalked through the hospital at night. Kirsten resists the treatment of her psychiatrist, Dr Stringer (Jared Harris), and engages reluctantly with the other patients, Iris (Lyndsay Fonseca), Emily (Mamie Gummer), Sarah (Lyndsy Fonseca), and Zoey (Laura-Leigh). Kirsten has visions of a dark shape, but after a corpse-like figure attacks her in the shower, she is unable to convince the authorities about what happened. She tries to escape several times but is unsuccessful. Eventually she learns that the other women had conspired to murder another patient, Alice (Mika Boorem). Alice’s ghost has returned to seek revenge. In addition to Tammy, the ghost murders Iris with a lobotomy needle, electrocutes Emily, cuts Sarah’s throat with a scalpel, and slays Zoey after she tried to flee with Kirsten. After reaching Dr Stringer’s office, Kirsten discovers from his case notes that he has been treating Alice for Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID, previously known as Multiple Personality Disorder [MPD]). It transpires that Alice had been kidnapped and held hostage for two months at age eleven in the farmhouse Kirsten had set on fire. Alice had subsequently invented the personalities of the patients of the ward as a defence mechanism. Killing off her alters had allowed her to confront her past and gradually heal psychologically. Kirsten and Alice’s ghost struggle before they leap through a second-floor window. A cut reveals the ‘real’ Alice lying injured and alone on the ground. It seems as if she has eliminated Kirsten, her last obstacle to a cure. Just before she is discharged in the care of her parents, Kirsten appears a final time and attacks her before the screen goes black.

On one reading, The Ward seems overly familiar to the point of being derivative. The ‘multiple personality explanation’ for the killings is similar to the scenario in Identity (James Mangold, 2003). In that film, ten people who converge at an isolated hotel are gradually murdered. We learn eventually that these people are alters of a death row prisoner (Pruitt Taylor Vince) who has a severe case of Dissociative Identity Disorder. His legal team and treating psychiatrist use this for a successful appeal against his sentence on the basis that the persona responsible for his crimes has been extinguished (this, of course, is not actually the case). The Ward employs stock characterisations: Iris is thoughtful and artistic, Emily is impetuous and erratic, Sarah is attractive, but manipulative, and Zoey is child-like to the point of carrying a toy rabbit. There are some ‘asylum’ tropes such as a tough female nurse, a well-meaning psychiatrist, and patients pretending to swallow medication. The film even includes “dark and stormy night” thunder and lightning flashes on several occasions.

Nonetheless, The Ward has some resonances with the slasher film, and therefore it refers implicitly to Halloween. Tammy, in particular, is stalked through the hospital before she is killed in a sequence that is typical of the subgenre. The ghost uses a scalpel and lobotomy needle, that is surrogate knives. These have often been read as phallic substitutes within the slasher film. As Carol Clover also points out, these weapons are used in preference to guns in the subgenre because of the view that “the emotional terrain of the slasher film is pre-technological”. [48] Killing in such fashion creates a sense of dread through the intimacy of its heavily embodied violence. The settings of the film also resonate with the slasher film. The farmhouse where the young Alice was held recalls the cannibal family’s dwelling in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974). The hospital functions like “The Terrible Place” because it is enclosed and frequently seems claustrophobic. [49] As with so many slasher films, there is a sense of inexorability about the killings because escaping to safety is not really possible.

Most significantly, though, is how the film engages with the figure of Final Girl, the protagonist/heroine of the slasher film who survives its carnage. The notional final girl in The Ward is the resilient and resourceful Kirsten, who outlives her colleagues. However, she is an invention of another final girl, Alice, who is also the killer with a traumatic past. Nor can we be sure who survives at the end of the film. Although Halloween is not the first slasher film, it established a template for dozens of other films. In his final film Carpenter returns to one of his vital contributions to the horror genre. He uses the deceptive simplicity of The Ward, its utter genericity, to modify and play with this figure. As final girl disappears or becomes a spectral figure, Carpenter also doubles or replicates her. Who is final girl in the film? Is she one or several? Is she victim, killer, or both? If, as Clover suggests, final girl in the slasher film embodies masculine and feminine qualities, then how do we interpret the gender of Alice/Kirsten, a character that incorporates an assortment of female clichés (kooky, sexy, rebellious, waif) displayed by ‘her’ surrogates? [50] The Ward, I would argue, poses these questions, but leaves them open or unresolved, as a good slasher film should.

Dis-figuration and Multiplicity

Alice’s ghost is deformed, wrinkled, and cadaver grey; she is another of the wounded bodies in the films I have discussed here. These texts are scarred with self-mutilation, decapitation, evisceration, infanticide, and torture, as well as exploding heads, stabbings, surreal births, anal abortions, severed angel’s wings, heads on sticks, or body parts used as trophy jewellery, as the Martian ghosts do. These traumatic figures can be interpreted as examples of what Julia Kristeva calls the abject. [51] As Barbara Creed writes, the horror film is replete with examples of abjection: “corporeal alteration; decay and death; human sacrifice; murder; [and] the corpse”. [52] If Carpenter’s creative nostalgia enables him to fashion an authorial presence through a negotiation with, and recombination of, genre films, then it is a particularly violent process in Ghosts of Mars, Cigarette Burns, Pro-Life, and The Ward. Carpenter does more than reverse the precepts of his own work or the horror genre, as he withdraws from the cinema, he defaces or extinguishes key examples from his own films, as well as surrogate figures like the angel or Dr Kiefer.

This self-conscious departure or erasure does not mean that ‘John Carpenter’ has vanished. Cigarette Burns and Pro-Life were made at the same time Carpenter remakes were released. As Carpenter dissolved himself and his legacy, his work was imitated and reproduced. Thus, it is an interesting coincidence that Carpenter’s final film is about multiple personality. DID/MPD patients usually cannot remember the experiences of their alters or multiple selves (such amnesia is a key symptom). Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen proposes that it is precisely this absence of the conscious self that facilitates the appearance of multiple identities. [53] In allegorical terms, Carpenter may no longer make films, but Carpenter films continue to manifest themselves. Indeed, there are signals that Prince of Darkness will be rebooted as a television program. Let me conclude by referring to a scene from that film involving Lisa (Ann Yen), a linguist who is decoding the ancient, multi-lingual tome kept by the priestly order that guarded the satanic vessel. She becomes possessed by the demonic force and types repeatedly on his behalf, “I Live! I Live! I Live!” So Carpenter does, even if his re-birth, his re-naissance, is disfigured by the violence of his abjection.

Dedication

This essay is dedicated to my friend, mentor, and fellow Carpenter aficionado, William D. Routt. Thanks Bill.

Notes:

[1] Raiford Guins and Omayra Zaragoza Cruz, “Revisioning: Repetition as Creative Nostalgia in the Films of John Carpenter”, The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror, edited by Ian Conrich and David Woods (London: Wallflower Press, 2004), pp. 155-166.

[2] Ian Conrich and David Woods, “Introduction”, The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror, p. 3.

[3] Adam Rockoff, Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film, 1978-1986, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002), p. 69.

[4] For a discussion of the reception of The Thing, see Vincent L. Barnett, “‘Instant Junk’: The Thing (1982), the Box-office Gross Factor, and Reviews from Another World”, Horror Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3 (2018), pp. 99-117.

[5] Conrich and Woods, “Introduction”, p. 3.

[6] Marco Lanzagorta, “John Carpenter”, Senses of Cinema 25 (2003)

http://sensesofcinema.com/2003/great-directors/carpenter/ Date accessed 1 November 2018.

[7] Steve Smith, “A Siege Mentality? Form and Ideology in Carpenter’s Early Siege Films”, The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror, p. 38.

[8] Richard Corliss, “Season’s Bleeding in Tinseltown”, Time, March 19, 1983, p. 56.

[9] Simon Sellars, “‘Flesh Dissolved in an Acid of Light’: The B-Movie as Second Sight”, Continuum: Journal of Cultural and Media Studies, Vol. 24, No. 5 (2006), p. 726.

[10] Kim Newman, “Vampires”, Sight and Sound, Vol. 9, No. 12 (1999), p. 60.

[11] John Kenneth Muir, The Films of John Carpenter, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000) p. 155.

[12] Roger Ebert, Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion, (Kansas City, Missouri: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 1992), p. 406.

[13] Philip Kerr, “In the Mouth of Madness”, Sight and Sound, Vol. 5, No. 8 (1995), p. 53.

[14] Desson Howe, “In the Mouth of Madness”, The Washington Post, February 3, 1995, p. 36.

[15] Todd McCarthy, “Village of the Damned”, Variety, May 1-7 (1995), p. 36.

[16] Lawrence Toppman, “Escape Sequel May Have You Asking ‘What Else Is New?’”, The Charlotte Observer, August 9, 1996. Quoted in Muir, The Films of John Carpenter, p. 179.

[17] Kim Newman, “Escape from L. A.”, Empire, 1 January 2011. https://www.empireonline.com/movies/escape-la/review/ Date accessed 1 November 2018.

[18] Michael O’Sullivan, “Vampires: A Vein Attempt at Horror”, The Washington Post, October 30, 1998, p. 65.

[19] Kim Newman, “Ghosts of Mars”, Sight and Sound, Vol. 11, No. 12, p. 60.

[20] Tom Whalen, “‘This Is About One Thing – Dominion’: John Carpenter’s Ghosts of Mars”, Literature/Film Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 4 (2002), p. 304.

[21] Derek Malcolm, “Carpenter’s Ghosts of Mars”, The Guardian, November 30, 2001, p. 13.

[22] Robert Koehler, “John Carpenter’s Ghosts of Mars”, Variety, August 19, 2001, p. 31.

[23] Kim Newman, “Ghosts of Mars”, p. 52.

[24] Philip Kerr, “Mars Bores”, The New Statesman, December 10, 2001, p. 44.

[25] Guins and Cruz, p. 155.

[26] See Noel Carroll, “The Future of Allusion: Hollywood in the Seventies (and Beyond)”, Interpreting the Moving Image, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 240-264.

[27] See Robert Cumbow, Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter, Second Edition, (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2000), pp. 147-164.

[28] See Steve Smith, “Form and Ideology”.

[29] See Cumbow, pp. 154-157.

[30] Cumbow, p. 149.

[31] Guins and Cruz, p. 159.

[32] Guins and Cruz, p. 156.

[33] Barry Keith Grant, “Disorder in the Universe: John Carpenter and the Question of Genre”, The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror, p. 13.

[34] Gains and Cruz, p. 164.

[35] Gains and Cruz, p. 164.

[36] See Kendall R. Phillips, Dark Directions: Romero, Craven, Carpenter, and the Modern Horror Film, (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Indiana University Press, 2002) pp. 140-142. Carpenter said in an interview, “I got into the movie business to make Westerns, that was my first love”. Ronald V. Borst, “An Interview with John Carpenter”, The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror, p. 169.

[37] Whalen, p. 304.

[38] Joseph Maddrey, Red, White and Blue: The Evolution of the American Horror Film, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004), p. 13.

[39] See Ben Kooyman. (2010). “How the Masters of Horror Master Their Personae: Self-Fashioning at Play in the Masters of Horror DVD Extras”, American Horror Film: The Genre at the Turn of the Millennium, edited by Steffan Hantke, (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2010) pp. 193-220.

[40] John Carpenter is a cigarette smoker.

[41] Guins and Cruz, p. 161.

[42] Colette Balmain, Introduction to the Japanese Horror Film, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh Press, 2008), p. 170.

[43] On torture porn and particular Hostel, see Jason Middleton, “The Subject of Torture: Regarding the Pain of Americans in Hostel”, Cinema Journal, Vol. 49, No. 4 (Summer 2011), pp. 1-24.

[44] The artist holds her severed head triumphantly in a similar manner to the Martian leader after he has killed a victim in Ghosts of Mars.

[45] Quoted in Muir, The Films of John Carpenter, p. 52.

[46] Muir, p. 52.

[47] David Woods, “Us and Them: Authority and Identity in Carpenter’s Films”, The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror, pp. 21-34.

[48] Carol Clover, Men, Women and Chainsaws, (London: British Film Institute, 1992), p. 31.

[49] Clover, p. 49.

[50] See Clover, pp. 53-64.

[51] See Julia Kristeva, The Powers of Horror: An Essay in Abjection, translated by Leon S. Roudiez, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982).

[52] Barbara Creed, “Horror and the Monstrous-Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection”, Screen, Vol., 27, No. 1, 1986, p. 46.

[53] Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen, “Who’s Who? Introducing Multiple Personality”, translated by Douglas Brick, Supposing the Subject, edited by Joan Copjec, (London: Verso, 1994), p. 61.