In his essay “Adaptation”, Mark Brokenshire suggests “Adaptation, as defined by the Oxford English dictionary, has a plurality of meanings most of which allude to the process of changing to suit an alternative purpose, function or environment”. [1] Citing the literary critic and scholar Linda Hutcheon, he states:

‘We experience adaptation as palimpsests through our memory of other works that resonate through repetitions and variation’ or in other words, the ways in which we associate the product as both similar to and different from the original. [2]

These definitions provide a useful filter through which to discuss Stanley Kubrick, a director whose own canon of work consists mostly of adaptations, as a source of adaptation, replication and appropriation himself. In this essay I seek to address, interrogate and offer an understanding of the post-Kubrickian (the encompassing theme of this dossier) in relation to the relatively critically neglected post-2000 films of Steven Spielberg. For expediency and efficiency’s sake I have chosen to draw from across a range of these films, those which I believe best exemplify and most clearly support my argument.

In presenting an analysis of the (inter-) textual relationship that exists between Kubrick and Spielberg, I observe a set of visual juxtapositions and overlapping concerns in terms of the presentation and construction of space, iconography, narrative, and text. Through a close reading of primary and secondary archival sources I propose that, in adapting Kubrick’s work, Spielberg films are both palimpsests (as Hutcheon describes the term) in the sense that the films both recall and (artificially) recreate the memory of Kubrick’s work through deliberately referential use of imagery, iconography, space and architecture, and yet remain profoundly auteuristic and Spielbergian.

In using the term ‘adaptation’ I am of course not claiming that Spielberg simply remakes (or has remade) specific films by Stanley Kubrick, but instead appropriates, adapts, remodels, and refits certain sets of imagery, iconography and tropes of Kubrick’s work in order to “suit an alternative purpose, function or environment” (as suggested by Brokenshire above). These films are, in the truest sense, post-Kubrickian: made and released after Kubrick had passed through the star field and out into the infinite in March 1999. While this article’s later focus will be on A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2002), in discussing a range of Spielberg’s films from after the turn of the millennium it will also observe their shared concern with constructed, architectural environments and structures of containment and isolation built by man for himself and around himself.

A.I. is the most famous point of interface between the two directors. Peter Krämer’s 2015 article “Adaptation as Exploration: Stanley Kubrick, Literature and A.I. Artificial Intelligence” broke new ground on the issues of adaptation and authorship which surround the film’s lengthy journey from page to screen. Krämer chooses to focus primarily on the history and process of Kubrick’s own (unrealised) adaptation of the Brian Aldiss source material, the short story “Supertoys Last All Summer Long” (1969) and for that reason, this article will not dwell on this well covered ground. Krämer suggests it is only possible to understand Spielberg’s A.I. as an adaptation of Aldiss’s story at a “stretch” [3] (due to the distance created by Kubrick’s numerous collaborations with different authors and its prolonged and agonised development history). Nevertheless he states:

Assuming that Kubrick and Spielberg were the key creative forces behind A.I. we might want to determine which of the two filmmakers was most responsible for the shape the film finally took, or whether, in the light of the perceived distances between them the film might best be understood not as a coherent whole but rather as a kind of palimpsest. [4]

This article proposes to complement Krämer’s work by focusing not on the Kubrick/Aldiss interface but on the Spielberg/Kubrick one; by not considering Spielberg’s film as an adaptation of Aldiss’ novella but, ultimately, as an unrealised Kubrick project. It will consider Spielberg’s A.I. as both symptomatic of a wider trend, in his post-millennium/post-Kubrick films to adapt and appropriate the distinctive visual, thematic and narrative features of Kubrickian cinema, and, in particular, the film in which the memory of Kubrick’s work is most clearly recalled through a set of inter- and meta-textual points of visual, thematic and narrative reference.

The film presents Kubrick as source of adaptation and had a complex developmental and production history, well documented by both Krämer (and elsewhere by Alison Castle [5]) and it stands as a pivotal moment in the Kubrick/Spielberg relationship, the definitive post-Kubrick text. Briefly, however, it began life as a Kubrick project, an anticipated adaptation of the Brian Aldiss short story. After a lengthy and failed 15-year development period, Kubrick proposed to Spielberg in the mid-1990s that he helm the project. The film was finally produced as the first film project by Spielberg after Kubrick’s death. In fact, Kubrick had optioned the text for adaptation in 1982 after seeing Spielberg’s own film about a lost, imperilled child looking for a way home to his parents, E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (1982). Note the similarity in title to A.I. Artificial Intelligence, suggesting that the Kubrick-Spielberg dynamic did not flow simply from only one direction.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (I)

The more negative criticism levelled at the film has tended to focus on the supposed incompatibility of the two authorial voices in the film. [6] However, of all Spielberg’s films it is the one that is the most marked and shaped by Kubrick’s legacy. A range of Kubrick’s own pre-production materials housed in the Stanley Kubrick Archive at the University of the Arts, London has formed the basis of my own original research. They include story development notes and treatments as well as concept art by the conceptual artist Chris Baker (a.k.a Fangorn) who collaborated not only with Kubrick, but also with Spielberg on the film’s idiosyncratic, intertextual and spatial design. Where these also form points of reference for Peter Krämer, I will use them to offer a close analysis of the presence and role of space and architecture, in the film and the construction of Kubrickian and Spielbergian filmic environments.

Of interest is an 89-page story treatment passed to Spielberg by Kubrick, to whom it was returned in 1996 complete with annotations and notes. This document offers a dialogue between the film’s two ‘parents’ (the film’s titles open with “An Amblin/Stanley Kubrick production”) and elicits questions of authorship, ownership, replication, and adaption that hang over the film – issues central to the narrative of the film. This story treatment, based on Kubrick’s collaboration with the sci-fi writer Ian Watson, also credited in Spielberg’s film, offers a prism through which to observe Spielberg’s adaptive process, approach to the text, and his deference to Kubrick and also his willingness to challenge the latter’s ideas.

Following Hutcheon (cited in Brokenshire), I will consider Spielberg’s film as a product “both similar and a departure from the ‘original’”. [7] However, understanding what the ‘original’ is (or could have been), and singling out Kubrick’s own voice remains problematic, owing to the highly collaborative nature of the project when it rested in Kubrick’s hands (and discussed in depth by Krämer). In discussing this archival material I aim to dispel certain myths which have developed around Spielberg’s film, particularly in relation to its much criticised, supposedly sentimental ending.

Spielberg, Space and The Post-Kubrickian

In his introduction to The Cinema of Steven Spielberg: Empire of Light [8] Nigel Morris offers a provocative and polysemic reading of the phrase ‘the cinema of Steven Spielberg’. Teasing out a multiple set of meanings, he audaciously proposes Spielberg’s auteur status and, furthermore, proposes him (in a claim that may have previously seemed counterintuitive and paradoxical) to be an auteur of popular and commercial cinema – this tension helps illuminate some of the more problematic aspects of A.I. as I will later discuss.

Borrowing Morris’s approach I offer a similarly polysemic reading and understanding of what is referred to as ‘post-Kubrick’, with three readings with which to frame this discussion:

1. a set of films and film makers who follow in Kubrick’s wake and in whose work we may discern an iconographic, stylistic, technical or thematic influence and resonance

2. the re-drawing and re-interrogation of (cinematic) space and architecture made possible by 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

3. a consideration of Postmodernism with all of its implications of the replication, homage, adaptation, appropriation, self-reference, and intertextuality (all well documented aspects of Kubrick’s cinema itself).

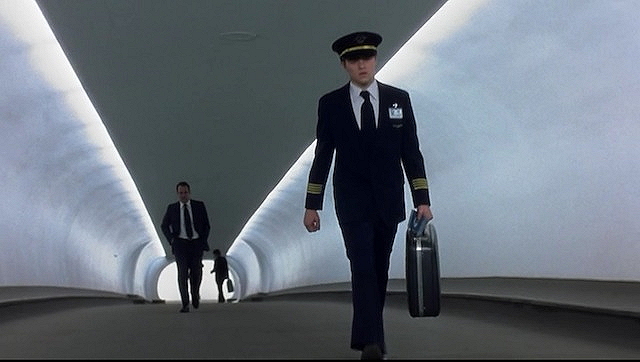

From here it is possible to begin mapping some interesting and potentially significant co-incidences across the careers of both directors. [9] The comedy-drama/caper film Catch Me If You Can (2002) resonates clearly with Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975). Based upon the autobiography of the fraudster Frank Abignale Jr, it is a period/costume drama set during the early 1960s about a dissolute young man who embarks on a picaresque journey, assuming a set of different identities and disguises (a notable Kubrickian trope which manifests in other films such as A Clockwork Orange [1971] and Eyes Wide Shut [1999], where mask and disguise play a prominent narrative role), cheating and defrauding his way up the social ladder before an inevitable fall. Abignale is presented as an isolated, lost and placeless figure, a body cast adrift in the space of the new society of the 1960s, just as Redmond Barry ultimately is, within the eighteenth century society through which he moves.

In her essay “Painterly Immediacy in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon”, Tatjana Ljujić offers a menu of visual styles and influences from across eighteenth and nineteenth century western art which frame and contextualise the film’s staging, style, mise en scène, and period authenticity. Challenging the assumption that the work of eighteenth and nineteenth century British artists like Constable, Hogarth, and Gainsborough dominate the frame, Ljujić offers a roster of European visual sources based on evidence found in the Kubrick Archive which include (among others) the nineteenth century realist painter Adolph Menzel, the French landscape artist Camille Corot and the Russian realist painter Nikolai Ge. Ljujić also suggests that Kubrick’s use of cinematic chiaroscuro owes more to earlier European painters like Caravaggio and Rembrandt. She suggests that:

Kubrick’s use of eighteenth century art in making Barry Lyndon was aimed at creating a visually absorptive and emotively involving spectatorial experience and not producing mistrust in art’s ability to represent history or at distancing the viewer from the imaged world. [10]

With Catch Me If You Can Spielberg reaches for a similar visual immediacy and spectatorial experience which adopts and appropriates the visual language and commercial styles of the American mid-twentieth century, immersing the viewer. As Nigel Morris explains, the film:

Overlays contemporary style and sensibility on attitudes and fantasies prevalent in mainstream entertainment from the 1960s setting, an era rippled with sophistication and innocence, manifested in both Frank Jr and his dupes. Self-consciously arty credits, accompanied by John Williams cool, Mancini-inspired score, set the tone. Flat animated graphics, characteristic of the period recall The Pink Panther (1963), the Bond series, The Charge of the Light Brigade and sequences by Saul Bass. They are straight, affectionate pastiche, not parody. Spielberg’s trademark shooting stars accompany the director’s credit, harnessing these old fashioned elements to his vision. [11]

The airline brand Pan-Am, synonymous with the 1960s and the by-word for (then) contemporaneity, style, prestige, travel, transatlanticism and the traversing of space, plays a prominent role in Catch Me If You Can – where Abignale Jr, adopts the persona and disguise of a Pan-Am airline pilot – just as it does in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1969). Images of flight, and suspension in space are recurrent throughout Kubrick’s cinema whether it is in images of the Pan-Am branded space travel of 2001 or in the famous opening ‘fly-over’ shot of The Shining (1981) as the camera glides over the mirror-like lake, moving to pick up the Torrance’s car as it wends its way along the surrounding mountain highway (an image of circularity and containment). Here the free floating, untethered and suspended camera signifies disembodiment, the uncanny, and anticipates the steady-cam shots that rove the corridors and sinister empty spaces of the Overlook Hotel later in the film.

In A.I. Spielberg adapts and re-purposes this shot when introducing ‘The Specialists’ (as they are referred to in the Ian Watson/Brian Aldiss credited screenplay), when their cubic craft glides over the frozen wastes of future Manhattan. Spielberg adapts its function, environment and purpose to suit a more benign, personal viewpoint and relocates it within a different narrative environment.

Stephen Mamber offers a set of overlapping spatial categories which he suggests are central to understanding what defines the ‘Kubrickian’ at both an aesthetic and textual level. Mamber’s critical study provides a useful and original lens for this discussion, through which we may note certain spatial parallels between the works of the two directors. The world of Spielberg’s Catch Me If You Can inhabits what Mamber observes (in relation to Kubrick) as “Game-Ritual-Warspace”. [12] Kubrickian narratives, he claims, are replete with games and play. War becomes a game (as evidenced in Full Metal Jacket [1987]); ball throwing, maze navigation and the invitation to “Come and play with us Danny” in The Shining; chess in 2001; and the game of table tennis which turns deadly in Lolita (1962). In Kubrick’s cinema, games and play are associated with danger and threat. Kubrick engages the viewer in games, tests and rituals, inviting the viewer to read his films both intertextually and meta-textually, giving the viewer pieces of a puzzle to be worked out (the confusing and seemingly impossible interior layout of the Overlook Hotel for instance, or the lack of explanation as to why Jack appears in the picture at the end of the film). Mamber states:

The role of the game, especially chess, has been widely recognised, but perhaps the construction of the game space hasn’t. We can find ample evidence that Kubrick’s films construct this space and that not only is there a game space, there are games of space … Camera movements representing game moves, chesslike and authorial are a component of Kubrick game space too. The game is in the calculation, the awareness that the movement is planned, though the characters being filmed don’t know it. [13]

In Catch Me if You Can the cat-and-mouse game between Abignale Jr (Leonardo DiCaprio) and FBI agent Carl Hanratty (Tom Hanks) plays out like a meticulously calculated game of chess with each one manoeuvring the other across a varied set of constructed and global spaces and environments until finally a détente, or stalemate, is reached between the two.

In A.I. , when robot child David finally comes face to face with his creator Professor Hobby (William Hurt), it becomes apparent that Hobby has been calculating and controlling David’s trajectory back to him with a trail of ‘breadcrumbs’ (like Wendy and Danny in The Shining), one of which is the ‘Oz’ like ‘Doctor Know’ and his instruction to David to go seek ‘The Blue Fairy’.

The landscapes and built environments of both Spielberg and Kubrick are inhabited by lost and displaced characters cast adrift in cinematic oceans of space, quite literally in the case of Martin Brody in Jaws (1975) and the robot child, David in A.I. . When David plunges beneath the depths from atop of a Manhattan skyscraper he is framed suspended in the water, silent, unmoving, arms outstretched in a shot which mirrors the image of the imperilled astronaut Poole in 2001: A Space Odyssey, untethered and free floating in zero gravity. Even Dr Bill Hartman (Tom Cruise) in Eyes Wide Shut (1999) disengages from the family unit and becomes an absent, lost and seemingly suspended body in space (as he aimlessly meanders through the streets of New York).

Kubrick and Spielberg also share a sense of displacement, of being ‘adrift’. For Spielberg this stems from the tension between his peripheral proximity to the New Hollywood of the 1970s, and his fame and renown as the world’s foremost director of popular, commercial/family cinema. This tension is embodied in his 1975 breakthrough film Jaws, which was released towards the end of the New Hollywood movement and is popularly thought of as both exemplary of it and bringing it to an end, ushering in a new era of studio ‘blockbuster’ cinema. Kubrick left Hollywood for England in the early 1960s, relocating there permanently in the mid-1960s, just as the studio system was collapsing and the independent and auteurist directors of the New Hollywood were beginning to emerge. He remained outside of this new movement but, working as an independent, was greatly admired by them (Spielberg in particular).

Kubrick is an evasive figure in this context, due not only to his own transatlanticism, but also due to the exceptionalism of his films. For instance, this is demonstrated by his choice in Barry Lyndon to not only adapt Thackeray’s novel but also to adapt the recognisably English painterly styles of Gainsborough, Constable and Hogarth (as well as the styles of other eighteenth and nineteenth European artists, as noted by Ljujić earlier) in both the framing, lighting and composition of the shot as well as the ‘surprise’ casting of American actor Ryan O’Neal as the itinerant Irishman Redmond Barry. This results cumulatively in cognitive dissonance. Similarly in Full Metal Jacket Kubrick transformed previously recognisable parts of East London (complete with palm trees) and Kent into war-torn Vietnam. Kubrick’s dissonant use of Beckton Gasworks as a location is discussed in detail by Karen A. Ritzenhoff, in her chapter “‘UK Frost can kill palms’ Layers of Reality in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket”. [14] Ritzenhoff reproduces two letters from the Kubrick Archive, one detailing Kubrick’s request to North Thames Gas to film at Beckton Gasworks [15] and a response from NTG offering their permission. [16] One might argue and hypothesise that the dissonance which is exhibited here also exhibits a contested, placeless, identity as both an American and British film maker.

Built Environments, Circularity, and World Building

Stephen Mamber cites Michel Chion to sum up Kubrick’s work as an “art of space”. [17] Such a summary prompts immediate thoughts of the locale for the duel between Redmond and Lord Bullingdon in Barry Lyndon – the cavernous, poetic, and cathedral-like space of the tithe barn with its shaft of light, painterly arrangement of figures and doves in flight; or the sterility and minimalism of the spaceship interiors in 2001 around which Poole jogs, like a hamster in a wheel, between coffin-like cryochambers; or the monochrome space of the ‘War Room’ in Dr Strangelove, with its ordered, circular arrangement. The latter is an example of what Mamber categorises as Kubrickian ‘Institutional-Official Space’ [18] within whose contours order, authority and rationality comically and satirically dissolve (“Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here! This is the War Room!”)

Circular narratives, imagery, mise en scène, motif and architecture permeate, pervade and repeat across Kubrick’s work. Mamber relates this to the presence of ‘Game Space’ in Kubrick:

Game space is repeatable: we can return and play again, perhaps with new contestants or the same ones again. The Shining is the ultimate repeatable game space, the narrative repetition, the circularity, of Kubrick’s films has always emphasized the sense that playing games, repeating duels, fighting battles is all that people do. The return of the monolith or the cut from bone to space station are not just narrative repetitions – they signal that the game is about to start over, just as General Turgidson in Dr Strangelove is planning to start over as soon as survivors can leave the mineshafts after impending nuclear annihilation. [19]

Circularity is the key organising principle of many of Kubrick’s set-ups and carries multiple inferences and meanings. It is another example of the partitioning and segregating of space and environment that occur routinely in Kubrick’s work and which also a feature regularly in Spielberg’s cinema. Spielberg’s cold war drama Bridge of Spies (2015) does not necessarily exhibit an overtly Kubrickian aesthetic, yet it is nevertheless a film that deals with and depicts the partitioning of both geographical space and mise en scène. For example, the division of East and West Berlin occurs early and throughout in the film by the arrangement of opposing characters, facing each other from the left and right of the screen, reminiscent of 2001’s Bowman and Pool in the escape Pod being covertly watched by Hal. This scene also reflects the film’s historical, cold war and geographical context, a period rife with covert observation and surveillance.

Mamber categorises another key mode of Kubrickian cinema as ‘Geometrical Space’ suggesting that across the oeuvre:

Visual symmetry marks off a walled, enclosed space, confined made even more geometrical by the limits of the frame. [Michel] Chion correctly labels space in Kubrick as centripetal, ‘attracting attention to what is at the centre’, rather than centrifugal as in the work of directors like Hitchcock or Bresson, who direct interest beyond the frame. [20]

Circular spaces, forms and frames frequently operate as portals for observation in Kubrick’s work with the most famous example being the circular, glowing red eye of Hal. In Dr Strangelove, we look down, covertly, upon the War Room through an expanded oval of light, a space of containment (and imprisonment) for the figures seated inside and which seems to expand against and challenge the contours of the frame.

A similar arrangement is evident in Spielberg’s A.I. – the ‘Specialists’ observe David’s meeting with the ‘Blue Fairy’ (which they have fabricated) through a similar overhead portal. Earlier in the film David is framed through a circular aperture at the dinner table and he later appears again framed through yet another corresponding aperture in Professor Hobby’s study, only this time its circularity is broken (like the family unit). Furthermore, as David’s surrogate human mother, Monica (Frances O’Connor), drives away abandoning him, we view David receding into the distance in the circular wing mirror of the car.

In Spielberg’s adaptation of the Roald Dahl children’s classic The BFG (2016), the audience is presented with a set of partitioned spaces across which characters move back and forth. The ‘Parody space’ [21] of London at the beginning and the early depiction of the Orphanage closely references both the Overlook Hotel and the arrangement of the dorms in Full Metal Jacket, as does the (literal and narrative) alternative and ‘unworldly’ ‘dream space’ of ‘Giant Country’ towards the end. Mamber defines this ‘Parody space’ thus:

Starting with the décor, there is a too-muchness, an obsessiveness that makes spaces seem extreme, not just beautiful and repellent (though certainly those) but ironic, comic and exaggerations of ordinary spaces. [22]

Here the computer generated, parodic and artificial landscape ironically recalls that of Barry Lyndon in its immersive and immediate painterly aesthetic, staging, and mise en scène. The BFG’s home is also frequently framed through a circular aperture in a rock formation which partitions and divides the space of the screen.

A.I. offers a contrasting range of overlapping spaces, from the institutional to the parodic and postmodern to the dream space (which dominates the final act of the film as David meets ‘The Blue Fairy’ and finally goes ‘to the place where dreams are made’). There are contrasts throughout between sterile domestic and ‘Institutional’ spaces and verdant dreamlike green spaces (e.g. forests) that anchor the film to its (sinister) fairy tale narrative framework and embolden it. Conversely, in the film treatment at the Kubrick Archive, the green spaces, are explicitly the result of radioactive mutation around the ‘Robotics Institute’. [23]

Spielberg’s romantic comedy-drama The Terminal (2004) appropriates the previously mentioned Kubrickian ‘institutional-official’ space, which Stephen Mamber describes as:

All things man-made. The Space station [in 2001], the meeting rooms of Dr Floyd and his colleagues, the working areas of the discover – all reflect a manufactured, sanctioned ‘government like space’. Even the Louis XVI style bed room in which Bowman lives and ages before his transformation into the ‘star-child’ has been recognized as possibly either a constructed by aliens observation zoo-like room, a space of confinement or a dreamlike vision of a regal deathbed … too much regularity and bureaucratic sensibility to reflect well upon those who constructed the space. [24]

Referring back to criteria (2) and (3) of the earlier outlined post-Kubrick definitions it is useful to note how Spielberg not only references this type of spatial engineering and architecture but also adapts and repurposes it (literally in the case of The Terminal) into a recognisably ‘comforting’ Spielbergian space. Vicktor Navorksi (Tom Hanks), a citizen of the fictional Eastern European state of Krakovia, is marooned in the airport terminal at JFK due to the outbreak of civil war in his home country. Due to an administrative and bureaucratic loophole, Navorksi is prevented from leaving the airport terminal and entering onto American soil. He becomes a stateless body, cast adrift in the cavernous terminal space – a sterile, post-modernist, cathedral of moving walkways, split levels, elevators, television screens and shops (he is told the only thing he can do, is to shop). Trapped within the terminal he is under constant observation from the Hal-like surveillance camera, the mechanical embodiment of the head of security (Stanley Tucci). It is the epitome of Kubrickian man-made institutional-official space: a cavernous, purpose built, techno-space of surveillance, containment, order, control and movement, hermetically sealed from the outside space of Manhattan. It also demonstrates in its scale, space and aesthetic the influence of set designer and Kubrick collaborator Ken Adam (Dr Strangelove and Barry Lyndon).

Yet, over the course of the film Navorski physically sets about rebuilding parts of this technocratic and dystopian (Kubrickian) space into a Spielbergian space – converting a wall in an ancillary part of the terminal that is due for refurbishment into a more ornate and decorative version (and thereby creating a space within a space). The act turns a cold and threatening space into a comforting (and ultimately romantic) space. Furthermore Navorski converts a wall of urinals, which are framed by the camera to look like the nightmarish lift doors in The Shining, into a mosaic for his potential love interest, Amelia (Catherine Zeta-Jones).

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (II)

Upon its 2001 general release, while not an outright commercial disaster, A.I. was met with mixed critical response. According to Sergi Sanchez:

Critics like Jonathon Rosenbaum and J.Hoberman insisted after the premiere that A.I. Artificial Intelligence was the product of two seemingly opposite sensibilities: Stanley Kubrick, who promoted the project and Steven Spielberg’s inspired replicant. [25]

The Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw dismissed the film as a “curious appendage to the canon of both men” [26], stating:

If Kubrick had made this 30 years ago as a story of a ‘Star Child’ whose spiritual trajectory spans thousands of years, it might have been stunning. Instead he made 2001: A Space Odyssey. If Spielberg had made it 20 years ago about an adorable, unearthly creature estranged from human love, that too might have been stunning. Instead he made E.T.. [27]

Jake T. Bart suggests that:

A.I. is notable for its reworking of recurring Spielberg motifs into a darker form. Loneliness pervades A.I. Spielberg presents the recurring image of David suspended underwater, arms outstretched, eyes wide with anticipation hoping for human contact. The epilogue, which reunites David with his mother, or rather, a projection of his mother, for only a single day, is not a classic Spielbergian balm. The openly philosophical nature of the film … turned off audiences and puzzled critics. [28]

Here Bart indicates that, far from the downgrading of Kubrickian elements in favour of those associated with Spielberg, in fact Spielberg adapts to Kubrick. I would like to propose that the mixed reaction to A.I. was in part a result of certain prejudice against Spielberg’s role in the project – as a director of popular cinema (and therefore further down the auteurist pantheon) who was at odds with the distinctive vision and voice of Stanley Kubrick. To understand, if not reconciling this response, it is important to remember that:

(1) Spielberg was Kubrick’s first (and only) choice to take charge of the project after he had seen Jurassic Park (1993). Previous to that the technology had not been available to successfully create a computer-generated boy (as Kubrick had wished) and he was unable to use a real boy actor (he would naturally age over the course of shooting the film). [29]

(2) Spielberg was adapting a treatment of a story, which emerged out of Kubrick’s collaboration with science fiction author Ian Watson into a Steven Spielberg film. The film is a posthumous homage to Kubrick, his friend.

The 89-page treatment [30] in the Stanley Kubrick Archive, dating from 1996 (five years before Spielberg made the film), offers some insights into A.I.’s gestation. Spielberg’s annotations support a form of dialogue between these two (allegedly) competing voices. In fact, Spielberg’s film adheres fairly closely to this document and his notes suggest areas of narrative to be cut mainly for expediency. Spielberg, also appears to want to soften some of the crueller elements, such as Monica telling David he can only come home when he is a ‘real’ boy, giving him false hope. This statement does not appear in the film. Spielberg ultimately softens Monica’s character when she tells David “I wish I could have told you about the world” before leaving him behind. What may be suggested from these annotations is that Spielberg’s approach to the story was to streamline it and create a more economical narrative, as well as to tailor it to his familiar ‘family’ audience sensibility.

However, Spielberg appears to be responsible for the character development of Teddy (the ‘Supertoy’ given to David, and who in the film becomes the most stable parental figure and guide), whom he suggests in his notes “Must be more of an active conscience” [31] , a ‘Jiminy Cricket’ character. This intervention shows that while Kubrick anchored his text to Colodi’s Pinocchio, Spielberg seems to have Disney in mind.

An extended close reading and comparative analysis of this document is outside the scope of this essay. However, there are a number of significant similarities and discrepancies worth highlighting. Much of the criticism levelled at the A.I. was centred around its apparent sentimentality, particularly in relation to the ending in which the ‘Specialists’, some 2000 years into the future, allow David one more ‘happy day’ with his ‘mother’ Monica, at the end of which she dies and David lies down, finally able to sleep contentedly.

The ‘Specialists’ (the evolved beings who discover David after two millennia) are also at the interface of Kubrick and Spielberg. In the treatment handed to Spielberg by Kubrick, they are highly evolved, sentient robots, whereas in in Spielberg’s film their identity is a mystery. They are iconographically resonant, however, with the Spielbergian aliens of Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977). [32]

Critics of the film have attacked this ‘soft’ ending as being un-Kubrickian and an example of the incompatibility of these two artistic visions. It is therefore somewhat surprising to note that in Kubrick’s treatment the ending is much softer than in Spielberg’s film. In Kubrick’s outline, David’s love for Monica creates a miracle and she is able to stay with him for eternity.

This ending also seems incongruous with some of the harsher aspects of the treatment, with its opening intimations of eugenics and the creation of a ‘perfect’ improved child. Both the film and the 1996 treatment (the only one to contain notes by Spielberg) contain certain aspects of holocaust imagery. Kubrick attempted to get the film made in the early 1990s after his Holocaust film, The Aryan Papers, ran into direct competition with Spielberg’s 1993 release of Schindler’s List. The film’s paternal scientist, Hobby, is both a benign and grieving father as well as (paradoxically) a Josef Mengele figure, who in the film’s opening sequence, when demonstrating the pain response of a female robot, juxtaposes cruelty with kindness (Mengele, the Nazi eugenicist and camp doctor at Auschwitz, would famously encourage the camp children to call him ‘Uncle Josef’ and hand out sweets before selecting them for experimentation). David is both Aryan and Jew, a ‘perfect’ blond haired manufactured child, but who is also singled out at a pool party as ‘Mecha’ rather than ‘Orga’ by youths who proceed to cause him pain and attempt to look at his penis (thereby singling him out as different).

The treatment also presents Hobby, the creator/father, as a ‘Visionary’, further anchoring the text to cinematic ‘Dream space’. Hobby explains: “A robot brain is like the Mona Lisa painted by numbers … What I would like to suggest is that love will be the key to their acquiring a kind of subconscious, a deeper level of desire and dream.” [33]

Surveying the wealth of pre-production material in the Stanley Kubrick Archive, it becomes apparent that there is no clear, holistic or unifying vision of a ‘Stanley Kubrick’ film version, or at least not one that bears his authorial voice alone. In a folder pertaining to author Sara Maitland’s work on the project, in her correspondence with Kubrick, Maitland asks to what extent are contributors working to a Kubrickian agenda, or is the writers’ role to put their own ‘stamp’ on it? Similarly, Spielberg’s production is the only version of the film and the final gestation of a long, evolutionary process which has, inbuilt into its artistic DNA, the legacy of Kubrick’s many previous collaborations with a series of writers: Brian Aldiss, Ian Watson, Bob Shaw and Sara Maitland as well as concept artists such as Chris Cunningham and Fangorn (Chris Baker).

Indeed, Baker is central to the Kubrick/Spielberg interface on the film. He collaborated with both directors and is a clear bridge between the two approaches to the project. Baker visually connects them through a range of designs, sketches and drawings, which began under Kubrick and were appropriated and adapted by Spielberg. Fangorn’s sketches show how the look and postmodern aesthetic of the film was created over time (complementing the film’s narrative themes of authorship, replication, adaptation) but also in evoking the spatial design of the film. As identified earlier, often for both filmmakers the narrative world is constructed around a set of interconnected yet partitioned spaces. In the original concept artwork dating from 1994 (the year before Kubrick first approached Spielberg about taking on the project), there are over 300 designs, drawings and sketches for the various spaces depicted in the film, its robots and speculative technologies. There are protean designs for The Shanty Town (where David meets Joe); the Robotics Institute (not realised in Spielberg’s film) and Rouge City, a hybrid, postmodern city space of desire and wish fulfilment that melds noir, Las Vegas, expressionism, art deco and Egyptian iconography. The highly sexualised architecture and design of phallic towers and splayed, naked women with sensuous open mouths is also present in Spielberg’s film (if slightly toned down). It is a parodic space that incorporates aspects of the design of the mannequin furniture (naked, sexualised female bodies) present at the start of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange in the Korova Milk Bar.

A.I. contains numerous visual, iconographic references and textual correlations with A Clockwork Orange. The plain white attire that David wears when first introduced, and which we see later in the film worn by the other ‘Davids’ (for which he was the prototype), recalls the white costume of Alex and his Droogs. On first meeting David, Joe (Jude Law) executes the same dance Alex performs during the infamous ‘Singing In The Rain’ rape scene in A Clockwork Orange. When Joe, David and supertoy Teddy hitch a ride to Rouge City Spielberg evokes the shot of Alex and his Droogs piled into their car on the way to visit the ‘cat lady’. A.I. also strongly resonates textually with A Clockwork Orange. Both Alex and David are programmed children: Alex through the savage, behaviouralist Ludovico treatment and David through his ‘imprinting’ programme, enacted by Monica that compels him to ‘love’ (without choice), one designed to offer excessive, unadulterated love to satisfy the parental ego. Children who violently attempt to break their ‘social’ programming is a trope in Kubrick’s films. In A.I. David’s leap from the sky scraper echoes teenager Alex’s leap from the Writer’s window. If David is ‘imprinted’ to impersonate a ‘real’ child then one might argue that A.I. itself is ‘imprinted’ to echo and replicate key Kubrickian motifs.

Given the film’s narrative emphasis on parental replacement and adaption, further comparison can be drawn. Having found his way back to his creator Professor Hobby, David discovers he has been replaced by a new version of himself and that he is in fact no longer one of a kind. This sequence reprises Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange when Alex returns home after being ‘cured’ of his violent tendencies, only to discover his parents have effectively replaced him with lodger (Joe). Peter Krämer also recognises this parallel in the original Aldiss text, recognising “teenage Alex’s relationship with his parents and his wish to return home to them are central to A Clockwork Orange”. [34] Confronted by the ‘imposter’, David demonstrates a major break in his programming and rants violently “I’m David!” in an attempt to assert individuality and subjectivity. This conforms to the pattern of behaviour displayed by other Kubrick child characters and this sudden lapse into violence could be considered the point where David breaks from being a Spielbergian child (imperilled, sweet, innocent, and lost) into a Kubrickian one.

Questions of authorship raised by A.I.’s extended development also confer a layer of meta-textuality upon the film. From this perspective it is possible to understand A.I. as decidedly ‘post Kubrickian’. A.I. is fundamentally a film about authorship or, as it is expressed in the narrative, parenthood and the disassociation of child and parent and the replacement of both. A.I. has two parents – and a whole host of lesser ones, considering Kubrick’s multiple collaborators prior to Spielberg’s undertaking. As a cultural artefact it has assumed the appearance of a lost child, perhaps itself wishing to identify and reconcile its own subjectivity, as do Hal, Alex, Lord Bullingdon, Danny, the young soldiers in Full Metal Jacket, and of course David himself.

NOTES

[1] Mark Brokenshire, “Adaptation”, Chicago School of Media Theory, University of Chicago, [https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/adaptation/]

[2] Ibid.

[3] Peter Krämer, “Adaptation as Exploration: Stanley Kubrick, Literature, and A.I. Artificial Intelligence”, Adaptation, Vol.8 No.3 (August 2015) p. 373

[4] Ibid.

[5] Alison Castle, “Stanley Kubrick’s A.I.” in Alison Castle (ed.). The Stanley Kubrick Archives (London: Taschen, 2008) pp. 504-508

[6] In his review from 2001 in The Guardian newspaper, UK, critic Peter Bradshaw suggested, “In theory, Kubrick should play the salty Lennon to Spielberg’s sucrose McCartney. Or, to put it another way: Stanley provides the hi-tech high concept and Steven gives it the big, beating heart. But it turns out like George Bernard Shaw’s joke to the beautiful young woman who wanted to breed with him: what if the baby gets my body and your brains? A.I. winds up with Kubrick’s empathy and Spielberg’s intellectual muscle. It’s a lethal combination” [https://www.theguardian.com/film/2001/sep/21/1]

[7] Quoted at Mark Brokenshire, “Adaptation”, Chicago School of Media Theory, University of Chicago, [https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/adaptation/]

[8] Nigel Morris, The Cinema of Stephen Spielberg: Empire of Light (London: Wallflower Press, 2007) p. 1

[9] In 1952, Kubrick (then at the start of his career) worked as a second unit director on Mr Lincoln, a five-part TV bio-documentary, written by James Agee, on the life of Abraham Lincoln. Later Spielberg would make Lincoln (2011) an epic historical drama focusing on the last few months of the president’s life, based on Doris Kearn-Goodwin’s book Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. Spielberg’s account of Lincoln’s (here played by Daniel Day-Lewis) struggle with the House of Representatives over the 13th amendment clearly also signalled a contemporary resonance with Barack Obama’s own struggles with the House and as a supposed an upholder of liberalism and democracy during a time of political, economic and social crisis. This is an exercise in adaptation, not just in textual adaptation but in adapting and repurposing history. There is, however, no evidence (yet) to suggest that Kubrick’s work on the 1952 series had any impact on Spielberg’s film, but it is nevertheless interesting to note the symmetry, hence it is included here chiefly as an interesting aside.

[10] Tatjana Ljujić, “Painterly Immediacy in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon” in Tatjana Ljujić, Peter Krämer and Richard Daniels (eds.) Stanley Kubrick, New Perspectives (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2015) p. 238

[11] Nigel Morris, The Cinema of Stephen Spielberg: Empire of Light (London: Wallflower Press, 2007) p. 330

[12] Stephen Mamber, “Kubrick in Space” in Robert Kolker (ed.) 2001: A Space Odyssey – New Essays, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 58

[13] Ibid.

[14] Karen A. Ritzenhoff, “‘UK Frost Can Kill Palms’ Layers of Reality in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket” in Tatjana Ljujić, Peter Krämer and Richard Daniels (eds.) Stanley Kubrick, New Perspectives (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2015) p. 328

[15] Ibid, p. 329

[16] Ibid, p. 330

[17] Stephen Mamber, “Kubrick in Space” in Robert Kolker (ed.) 2001: A Space Odyssey – New Essays, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 56

[18] Ibid, p. 63

[19] Ibid, p. 58

[20] Ibid, p. 63

[21] Ibid, p.59

[22] Ibid.

[23] Stanley Kubrick Archive, London: A.I. Story Development and Treatment, ref: SK/18/3/1/4/15 p. 50

[24] Stephen Mamber, “Kubrick in Space” in Robert Kolker (ed.) 2001: A Space Odyssey – New Essays, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 53

[25] Sergi Sanchez, “Towards a Non-Time Image: Notes on Deleuze in the Digital Era”, Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st Century Film, [http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post-cinema/2-4-sanchez/?pdf=227]

[26] Peter Bradshaw, “A.I. Artificial Intelligence” The Guardian UK, [https://www.theguardian.com/film/2001/sep/21/1]

[27] Ibid.

[28] Jake T.Bart, “Moral Anxiety, Mortal Terror: Considering Spielberg Post 9/11” Cinesthesia: Vol. 4. Iss. 1, Article 2 (November 2014) p. 2

[29] Alison Castle, “Stanley Kubrick’s A.I.” in Alison Castle (ed.). The Stanley Kubrick Archives (London: Taschen, 2008) p. 505

[30] Stanley Kubrick Archive, London: A.I. Story Development and Treatment, ref: SK/18/3/1/4/15

[31] Ibid, p. 15

[32] They also recall the sculptures of both Alberto Giacometti (in their statuesque-ness) and Henry Moore (in their marbled, stone-like texture) illustrating two different approaches to sculpting and ‘recreating’ the body. Here we see, in their design, a dualistic aesthetic and artistic approach which reminds us of the Kubrick/Spielberg dualism also. They are read as aliens ONLY by their association with Spielber and I would like to suggest that these ‘Specialists’ are like Kubrick’s Monolith (or Spielberg’s shark): blank spaces onto which meaning might be projected and which support ‘mythology’.

[33] Stanley Kubrick Archive, London: A.I. Story Development and Treatment, ref: SK/18/3/1/4/17 p. 1

[34] Peter Krämer, “Adaptation as Exploration: Stanley Kubrick, Literature, and A.I. Artificial Intelligence”, Adaptation, Vol.8 No.3 (August 2015) p. 375